Between-Session Reliability of Portable Isometric Mid-Thigh Pull and Countermovement Jump Tests in Elite Male Ice Hockey Players from the Swedish Hockey League

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Test Protocols

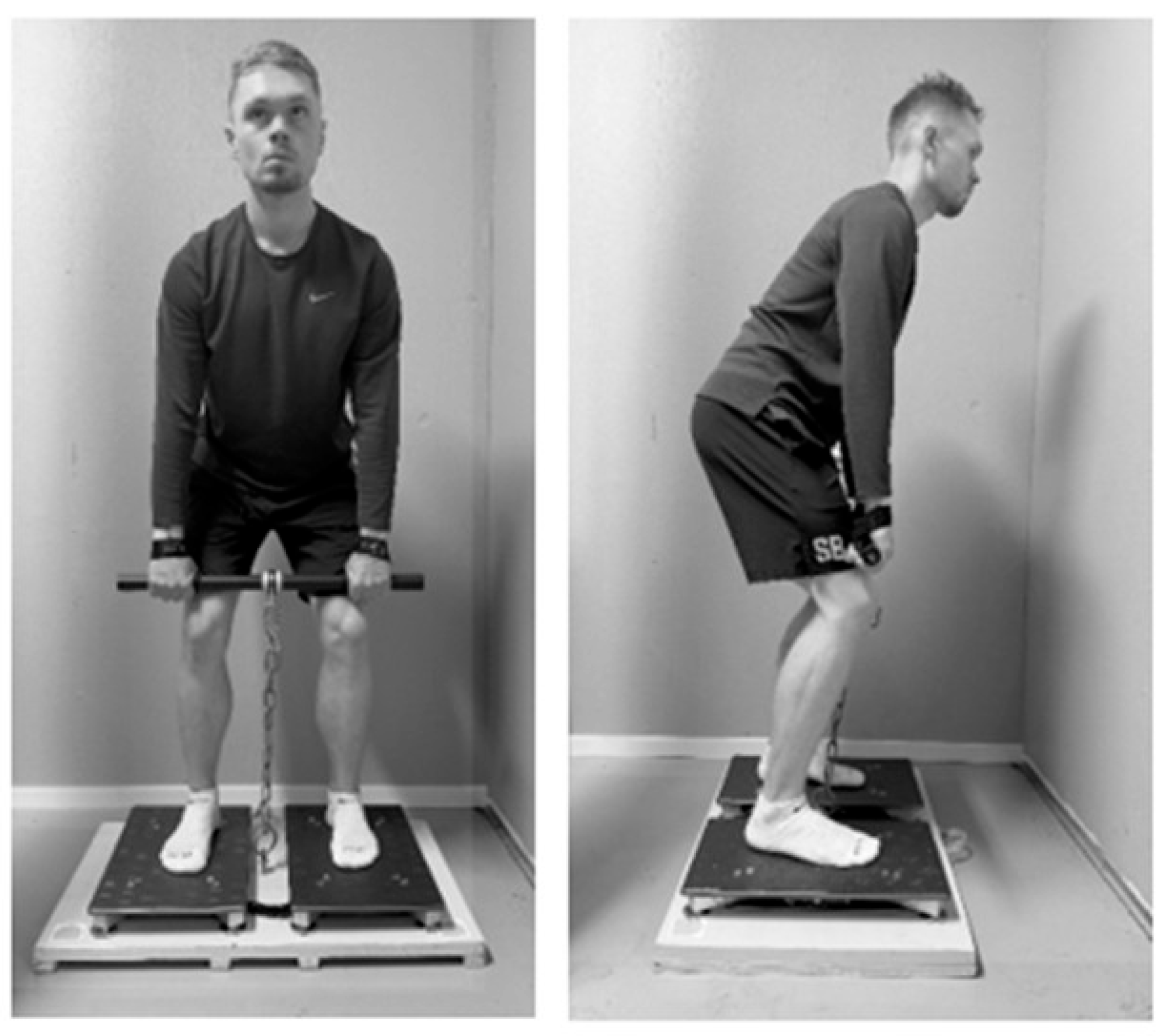

2.3.1. Isometric Mid-Thigh Pull

2.3.2. Countermovement Jump

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

4. Discussion

Practical Applications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brady, C.J.; Harrison, A.J.; Flanagan, E.P.; Haff, G.G.; Comyns, T.M. A comparison of the isometric midthigh pull and isometric squat: Intraday reliability, usefulness, and the magnitude of difference between tests. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2018, 13, 844–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claudino, J.G.; Cronin, J.; Mezêncio, B.; McMaster, D.T.; McGuigan, M.; Tricoli, V.; Amadio, A.C.; Serrão, J.C. The countermovement jump to monitor neuromuscular status: A meta-analysis. J. Sci. Med. Sport. 2017, 20, 397–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrigan, J.J.; Stone, J.D.; Hornsby, W.G.; Hagen, J.A. Identifying reliable and relatable force–time metrics in athletes—Considerations for the isometric mid-thigh pull and countermovement jump. Sports 2021, 9, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirniotou, A.; Katsikas, C.; Paradisis, G.; Argeitaki, P.; Zacharogiannis, E.; Tziortzis, S. Strength-power parameters as predictors of sprinting performance. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fitness 2008, 48, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vescovi, J.D.; McGuigan, M.R. Relationships between sprinting, agility, and jump ability in female athletes. J. Sports Sci. 2008, 26, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemdaroğlu, U. The relationship between muscle strength, anaerobic performance, agility, sprint ability and vertical jump performance in professional basketball players. J. Hum. Kinet. 2012, 31, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gathercole, R.; Sporer, B.; Stellingwerff, T.; Sleivert, G. Alternative countermovement-jump analysis to quantify acute neuromuscular fatigue. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2015, 10, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gathercole, R.J.; Sporer, B.C.; Stellingwerff, T.; Sleivert, G.G. Comparison of the Capacity of Different Jump and Sprint Field Tests to Detect Neuromuscular Fatigue. J. Strength. Cond. Res. 2015, 29, 2522–2531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, L.P.; Roberts, L.A.; Haff, G.G.; Kelly, V.G.; Beckman, E.M. Validity and Reliability of a Portable Isometric Mid-Thigh Clean Pull. J. Strength. Cond. Res. 2017, 31, 1378–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haugen, T.; Seiler, S.; Sandbakk, Ø.; Tønnessen, E. The Training and Development of Elite Sprint Performance: An Integration of Scientific and Best Practice Literature. Sports Med. Open 2019, 5, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopkins, W.G. Measures of reliability in sports medicine and science. Sports Med. 2000, 30, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laffaye, G.; Wagner, P.P.; Tombleson, T.I. Countermovement jump height: Gender and sport-specific differences in the force-time variables. J. Strength. Cond. Res. 2014, 28, 1096–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigh-Larsen, J.F.; Mohr, M. The physiology of ice hockey performance: An update. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2024, 34, e14284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigh-Larsen, J.F.; Beck, J.H.; Daasbjerg, A.; Knudsen, C.B.; Kvorning, T.; Overgaard, K.; Andersen, T.B.; Mohr, M. Fitness Characteristics of Elite and Subelite Male Ice Hockey Players: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Strength. Cond. Res. 2019, 33, 2352–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kierot, M.; Stendahl, M.; Warneke, K.; Wirth, K.; Konrad, A.; Brauner, T.; Keiner, M. Maximum strength and power as determinants of on-ice sprint performance in elite U16 to adult ice hockey players. Biol. Sport. 2024, 41, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keiner, M.; Kierot, M.; Stendahl, M.; Brauner, T.; Suchomel, T.J. Maximum Strength and Power as Determinants of Match Skating Performance in Elite Youth Ice Hockey Players. J. Strength. Cond. Res. 2024, 38, 1090–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farlinger, C.M.; Kruisselbrink, L.D.; Fowles, J.R. Relationships to skating performance in competitive hockey players. J. Strength. Cond. Res. 2007, 21, 915–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delisle-Houde, P.; Chiarlitti, N.A.; Reid, R.E.R.; Andersen, R.E. Predicting On-Ice Skating Using Laboratory- and Field-Based Assessments in College Ice Hockey Players. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2019, 15, 1184–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestri, M.A.; Cleather, D.J.; Callaghan, S.; Perri, J.; Legg, H.S. Examining the Determinants of Skating Speed in Ice Hockey Athletes: A Systematic Review. J. Strength. Cond. Res. 2025, 39, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grgic, J.; Scapec, B.; Mikulic, P.; Pedisic, Z. Test-retest reliability of isometric mid-thigh pull maximum strength assessment: A systematic review. Biol. Sport. 2022, 39, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petré, H.; Psilander, N.; Rosdahl, H. Between-Session Reliability of Strength- and Power-Related Variables Obtained during Isometric Leg Press and Countermovement Jump in Elite Female Ice Hockey Players. Sports 2023, 11, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moir, G.L.; Garcia, A.; Dwyer, G.B. Intersession reliability of kinematic and kinetic variables during vertical jumps in men and women. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2009, 4, 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moir, G.; Shastri, P.; Connaboy, C. Intersession reliability of vertical jump height in women and men. J. Strength. Cond. Res. 2008, 22, 1779–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansdell, P.; Thomas, K.; Hicks, K.M.; Hunter, S.K.; Howatson, G.; Goodall, S. Physiological sex differences affect the integrative response to exercise: Acute and chronic implications. Exp. Physiol. 2020, 105, 2007–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, D.N.; Bach, A.J.E.; O’Brien, J.L.; Sainani, K.L. Calculating sample size for reliability studies. PM&R 2022, 14, 1018–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weir, J.P. Quantifying test-retest reliability using the intraclass correlation coefficient and the SEM. J. Strength. Cond. Res. 2005, 19, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Koo, T.K.; Li, M.Y. A Guideline of Selecting and Reporting Intraclass Correlation Coefficients for Reliability Research. J. Chiropr. Med. 2016, 15, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warr, D.; Pablos, C.; Sánchez-Alarcos, J.; Izquierdo Velasco, J.; Redondo, J.C. Reliability of measurements during countermovement jump assessments: Analysis of performance across subphases. Cogent Social. Sci. 2020, 6, 1843835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maffiuletti, N.A.; Aagaard, P.; Blazevich, A.J.; Folland, J.; Tillin, N.; Duchateau, J. Rate of force development: Physiological and methodological considerations. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2016, 116, 1091–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrigan, J.J.; Strang, A.; Eckerle, J.; Mackowski, N.; Hierholzer, K.; Ray, N.T.; Smith, R.; Hagen, J.A.; Briggs, R.A. Countermovement jump force-time curve analyses: Reliability and comparability across force plate systems. J. Strength. Cond. Res. 2024, 38, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Guo, X.; Shi, Q.; Zhang, K.; Shen, Y. The concurrent validity of a portable force plate system for measuring isometric mid-thigh pull. J. Sports Sci. 2025, 43, 2631–2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collings, T.J.; Lima, Y.L.; Dutaillis, B.; Bourne, M.N. Concurrent validity and test–retest reliability of VALD ForceDecks’ strength, balance, and movement assessment tests. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2024, 27, 572–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dos’’Santos, T.; Jones, P.A.; Comfort, P.; Thomas, C. Effect of Different Onset Thresholds on Isometric Midthigh Pull Force-Time Variables. J. Strength. Cond. Res. 2017, 31, 3463–3473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Session 1 | Session 2 | 95% LoA | ICC (95% CI) | SEM | CV | MDC95 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome-oriented variables | |||||||

| Peak jump height (cm) | 41.9 ± 4.0 | 41.1 ± 3.9 | 0.8 (−2.8 to 4.4) | 0.89 (0.79–0.95) | 1.3 | 3.1 | 3.6 |

| Peak force (N) | 2244 ± 206 | 2240 ± 238 | 4 (−164 to 172) | 0.93 (0.86–0.97) | 59 | 2.7 | 164 |

| Peak force·BM−1 (N·kg−1) | 25.3 ± 1.6 | 25.2 ± 2.0 | 0.1 (−2.0 to 2.1) | 0.83 (0.68–0.92) | 0.7 | 2.9 | 2.0 |

| Peak power (W) | 4921 ± 472 | 4840 ± 435 | 81 (−229 to 391) | 0.93 (0.88–0.97) | 120 | 2.3 | 334 |

| Peak power·BM−1 (W·kg−1) | 55.6 ± 4.4 | 54.7 ± 4.4 | 0.9 (−2.6 to 4.4) | 0.91 (0.83–0.96) | 1.3 | 2.3 | 3.7 |

| Peak velocity (m·s−1) | 2.96 ± 0.14 | 2.94 ± 0.13 | 0.02 (−0.09 to 0.14) | 0.94 (0.86–0.97) | 0.03 | 1.4 | 0.09 |

| Concentric impulse (N·s) | 254 ± 20 | 251 ± 019 | 2.4 (−7.5 to 12) | 0.96 (0.93–0.98) | 3.9 | 1.4 | 10.7 |

| Eccentric impulse (N·s) | 138 ± 19 | 139 ± 18 | −1.6 (−13 to 10) | 0.95 (0.89–0.99) | 4.1 | 2.9 | 11.3 |

| Relative net impulse (N·s·kg−1) | 5.63 ± 0.26 | 5.65 ± 0.25 | −0.03 (−0.27 to 0.21) | 0.88 (0.78–0.94) | 0.09 | 1.5 | 0.24 |

| Time-dependent variables | |||||||

| Time to peak force (ms) | 512 ± 57 | 508 ± 59 | 4 (−6 to 7) | 0.86 (0.74–0.93) | 022 | 4.5 | 60 |

| Time to peak power (ms) | 719 ± 66 | 719 ± 69 | 0 (−10 to 10) | 0.76 (0.56–0.88) | 033 | 5.0 | 90 |

| Concentric duration (ms) | 273 ± 23 | 275 ± 23 | −4 (−22 to 13) | 0.93 (0.85–0.96) | 006 | 2.3 | 17 |

| Eccentric duration (ms) | 508 ± 47 | 503 ± 54 | 5 (−52 to 63) | 0.83 (0.68–0.92) | 021 | 4.1 | 58 |

| Variable | Session 1 | Session 2 | Bias (95% LoA) | ICC (95% CI) | SEM | CV | MDC95 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak force (N) | 3347 ± 388 | 3466 ± 344 | −119 (−312 to 273) | 0.92 (0.84–0.96) | 104 | 3.1 | 288 |

| Rate of force development (N·s−1) | |||||||

| 20 ms moving average | 13,224 ± 6864 | 13,639 ± 4142 | −414 (−10019 to 9190) | 0.64 (0.37–0.81) | 3402 | 25.8 | 9422 |

| 0–50 ms | 4769 ± 4087 | 4430 ± 2310 | 339 (−5817 to 6495) | 0.57 (0.26–0.77) | 2178 | 48.3 | 6032 |

| 0–100 ms | 6496 ± 4242 | 6978 ± 2812 | −482 (−6672 to 8294) | 0.62 (0.34–0.80) | 2205 | 36.7 | 6108 |

| 0–150 ms | 6602 ± 2639 | 6998 ± 2094 | −396 (−3675 to 2882) | 0.75 (0.54–0.88) | 1211 | 17.8 | 3355 |

| 0–200 ms | 6001 ± 1605 | 6447 ± 1605 | −446 (−2745 to 1854) | 0.73 (0.51–0.87) | 837 | 13.4 | 2319 |

| 0–250 ms | 5553 ± 1079 | 5839 ± 1451 | −286 (−2331 to 1760) | 0.67 (0.40–0.83) | 734 | 12.9 | 2033 |

| 50–100 ms | 8447 ± 4783 | 9832 ± 3938 | −1385 (−8692 to 5921) | 0.64 (0.36–0.81) | 2595 | 28.2 | 7186 |

| 100–150 ms | 8320 ± 2680 | 8917 ± 2813 | −597 (−5067 to 3873) | 0.66 (0.39–0.82) | 1607 | 18.7 | 4452 |

| 150–200 ms | 6328 ± 2668 | 6865 ± 2104 | −537 (−6670 to 5996) | 0.16 (−0.21–0.49) | 2322 | 54.6 | 6432 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Godhe, M.; Bergman, S.; Petré, H. Between-Session Reliability of Portable Isometric Mid-Thigh Pull and Countermovement Jump Tests in Elite Male Ice Hockey Players from the Swedish Hockey League. Sports 2025, 13, 456. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports13120456

Godhe M, Bergman S, Petré H. Between-Session Reliability of Portable Isometric Mid-Thigh Pull and Countermovement Jump Tests in Elite Male Ice Hockey Players from the Swedish Hockey League. Sports. 2025; 13(12):456. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports13120456

Chicago/Turabian StyleGodhe, Manne, Sebastian Bergman, and Henrik Petré. 2025. "Between-Session Reliability of Portable Isometric Mid-Thigh Pull and Countermovement Jump Tests in Elite Male Ice Hockey Players from the Swedish Hockey League" Sports 13, no. 12: 456. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports13120456

APA StyleGodhe, M., Bergman, S., & Petré, H. (2025). Between-Session Reliability of Portable Isometric Mid-Thigh Pull and Countermovement Jump Tests in Elite Male Ice Hockey Players from the Swedish Hockey League. Sports, 13(12), 456. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports13120456