Identity Work in Athletes: A Systematic Review of the Literature

Abstract

:1. Introduction

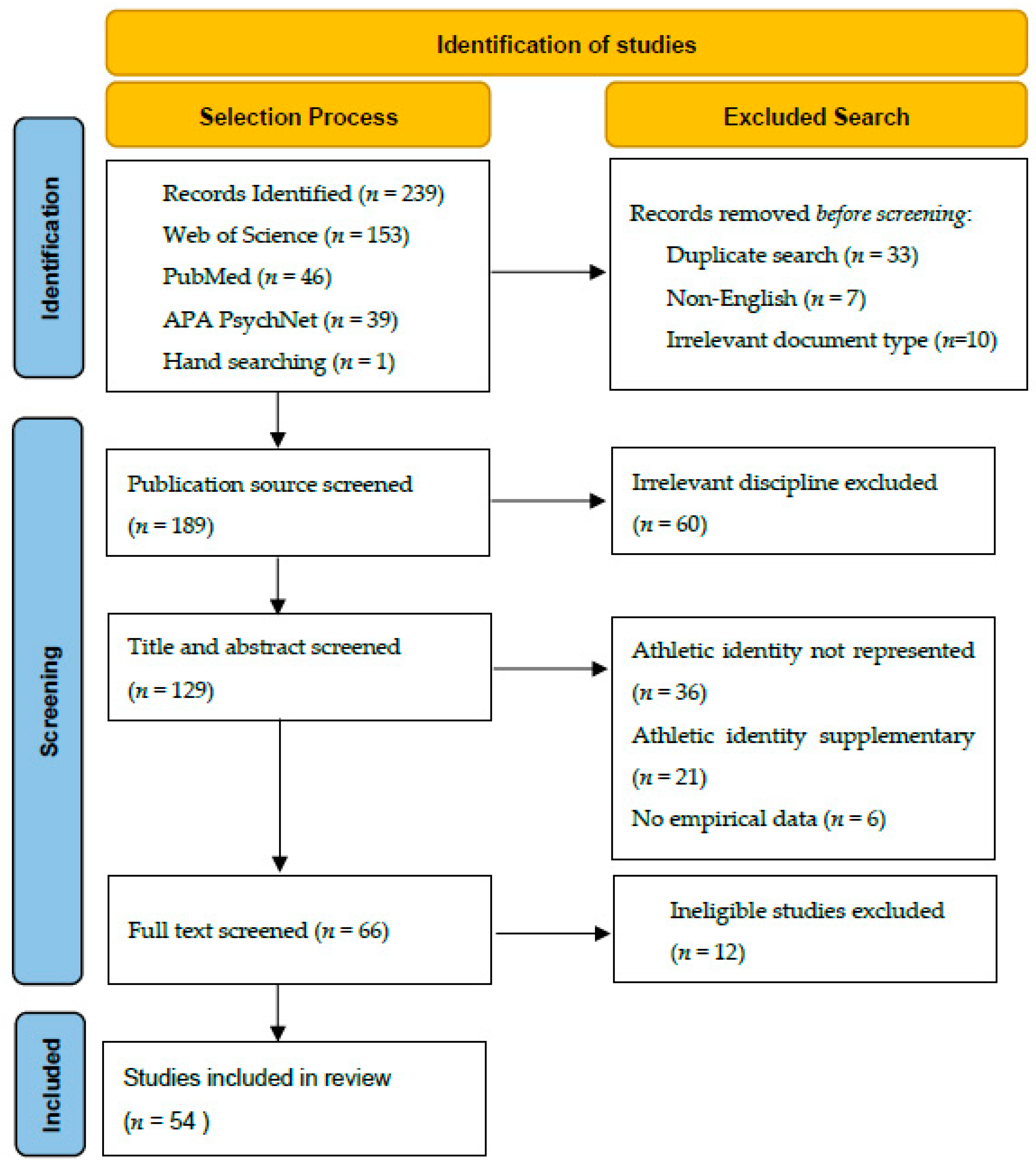

2. Methods

2.1. Article Selection

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Information Sources

2.4. Search Strategy

- “Athletic Identity”

- Work OR development OR formation OR management OR maintain*

- 1 AND 2

- Reference lists of retrieved studies were reviewed for hand searching.

2.5. Included Articles

2.6. Data Extraction and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Literature Characteristics

| Reference | Year | Aim/Focus | Design | Scale | Participants | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cornelius [49] | 1995 | Athletic identity and student developoment | Quant | AIMS | College students | 228 |

| Murphy et al. [50] | 1996 | Athletic identity foreclosure | Quant | AIMS | Student athletes | 124 |

| Martin et al. [51] | 1997 | Scale evaluation (AIMS) | Quant | AIMS | General athletes | 78 |

| Brown and Hartley [52] | 1998 | Athletic identity and career development | Quant | CDI | Student athletes | 114 |

| Martens and Cox [53] | 2000 | Athletic identity and career development | Quant | AIMS | College students | 226 |

| Miller and Kerr [29] | 2003 | Role experimentation, identity work, and student athlete transition | Qual | N/A | Student athletes | 8 |

| Hockey [54] | 2005 | Identity work in the face of prolonged injury | Qual | N/A | Injured distance runners | 2 |

| Phoenix et al. [55] | 2005 | Future aging, body, self, and athletes | Quant | AIMS | College students | 179 |

| Lally and Kerr [56] | 2005 | Career planning, athletic identity, and student role identity | Qual | N/A | College students | 8 |

| Jones et al. [57] | 2005 | Identity work and the role of coaches | Qual | N/A | Retired athlete | 1 |

| Killeya-Jones [28] | 2005 | Identity coherence and role discrepancy | Quant | Identity Collection Instrument | Student athletes | 40 |

| Nasco and Webb [58] | 2006 | Public and private dimensions of athletic identity | Quant | PPAIS | Retired athletes/sport participants | 677 |

| Anderson, Masse and Hergenroeder [48] | 2007 | Scale development (AIQ-adolescent) | Quant | AIQ | Adolescents | 2094 |

| Lavallee and Robinson [59] | 2007 | Identity work and transition | Qual | N/A | Retired gymnasts | 5 |

| Anderson and Coleman [60] | 2008 | Scale development (AIQ-adolescent) | Quant | AIQ | Elementary students | 936 |

| Anderson et al. [61] | 2009 | Athletic identity and physical activity | Quant | AIQ | Elementary and middle school | 1339 |

| Anderson [62] | 2009 | Identity development of adolescent girls with disabilities | Qual | N/A | People with Disabilities | 13 |

| Houle et al. [63] | 2010 | Identity work, age, and sport participation | Quant | AIMS | Student athletes/former athletes/non-athletes | 242 |

| Gapin and Petruzzello [64] | 2011 | Athletic identity and eating and exercise disorders | Quant | Not Specified | Runners | 179 |

| Tasiemski and Brewer [65] | 2011 | Athletic identity and post-injury participation | Quant | AIMS | People with disabilities | 1034 |

| Steinfeldt and Steinfeldt [66] | 2012 | Conformity to maculinity and athletic identity | Quant | AIMS | Student athletes | 523 |

| Verkooijen et al. [67] | 2012 | Athletic identity, burnout, and qulity of life | Quant | AIMS | Elite athletes | 123 |

| Carless and Douglas [6] | 2013 | Processes and consequences of identity development among young elite athletes | Qual | N/A | Elite male athletes | 2 |

| Perrier, Smith, Strachan and Latimer [27] | 2014 | Loss and restorement of athletic identity upon acquiring a physical disability | Qual | N/A | People with disabilities | 11 |

| Mitchell et al. [68] | 2014 | Athletic identity of elite English footballers | Quant | AIMS | Youth footballers | 168 |

| Yukhymenko-Lescroart [69] | 2014 | Academic identity and athletic identity predicting performance and persistence | Quant | AAIS | Student athletes | 187 |

| Poux and Fry [70] | 2015 | Motivational climate and athletic identity foreclosure | Quant | AIMS | Student athletes | 101 |

| Reifsteck et al. [71] | 2015 | Student athletes’ physical activity after college | Quant | AIMS | Student athletes | 282 |

| Benson et al. [72] | 2015 | Goal-discrepant threats and career development | Experimental | AIMS | Student athletes | 166 |

| Huang et al. [73] | 2016 | Athletic identity, college experiences, career self-efficacy, and barriers | Quant | AIMS | Student athletes | 345 |

| Sanders and Stevinson [74] | 2017 | Depressive symptoms among retired professional footballers | Quant | AIMS | Retired male footballers | 307 |

| Hickey and Roderick [75] | 2017 | Prsence and expectation of Possible selves, workplace identities, and athlete transitions | Qual | N/A | Professional football athletes | 10 |

| Ryba, Stambulova, Selänne, Aunola and Nurmi [13] | 2017 | Identity work during significant life events | Qual | N/A | Elite athletes | 18 |

| Foster and Huml [11] | 2017 | Athletic identity and academic major chosen | Quant | AIMS | Student athletes | 546 |

| Giannone et al. [76] | 2017 | Athletic identity and depression | Quant | AIMS | Student athletes | 72 |

| Rasquinha and Cardinal [77] | 2017 | Athletic identity, sport level, and cultural popularity | Quant | AIMS | College students | 385 |

| Chang et al. [78] | 2018 | Athletic identity and athlete burnout | Quant | AIMS | Student athletes | 132 |

| Anthony and Swank [79] | 2018 | Identity development of black college athletes | Quant | AIMS | Student athletes | 98 |

| Gustafsson et al. [80] | 2018 | Athletic identity and burnout | Quant | AIMS | Youth elite athletes | 448 |

| van Rens et al. [81] | 2019 | Career development, dual career athletes | Mixed Methods | AAIS | Student athletes | 8/86 |

| Ronkainen et al. [82] | 2019 | Identity work and role models | Qual | N/A | Adolescent athletes | 18 |

| Dean [83] | 2019 | Identity work and dealing with injury | Qual | N/A | Injury (student athlete) | 1 |

| Proios [84] | 2020 | Prediction of athletic identity | Quant | AIMS | People with disabilities | 134 |

| Hagiwara [85] | 2020 | Scale evaluation (Japanese version of AIMS) | Quant | AIMS | College students | 1514 |

| Andrijiw [86] | 2020 | Identity work and regulation | Qual | N/A | Professional hockey affiliates | 16 |

| Graupensperger et al. [87] | 2020 | Athletic identity, social support, and well-being | Quant | AIMS | Student athletes | 135 |

| Yukhymenko-Lescroart [47] | 2021 | Scale development (AAIS) | Quant | AAIS | College students/high-school students/student athletes | 989 |

| Monteiro et al. [88] | 2021 | Self-efficacy, career goals, and athletic identity | Quant | AIMS-Plus | Elite soccer players | 281 |

| Uroh and Adewunmi [89] | 2021 | Psychological impact of COVID-19 on athletes | Quant | AIMS | Multi-sport athletes | 64 |

| Haslam et al. [90] | 2021 | Social group membership infleunce | Quant | Job Deprivation Scale | Retired athletes | 398 |

| Zanin et al. [91] | 2021 | Identity work and turning points | Qual | N/A | Female youth soccer players | 28 |

| Cartigny et al. [92] | 2021 | Career development and self-efficacy in dual career athletes | Quant | AIMS/AAIS | Dual-career athletes | 111 |

| Brewer et al. [93] | 2021 | Scale development (athletic identity foreclosure) | Quant | SSMIF | Student athletes | 712 |

| Boz and Kiremitci [94] | 2021 | Athletic identity foreclosure | Quant | AIMS | Adolescent athletes/non-athletes | 2422 |

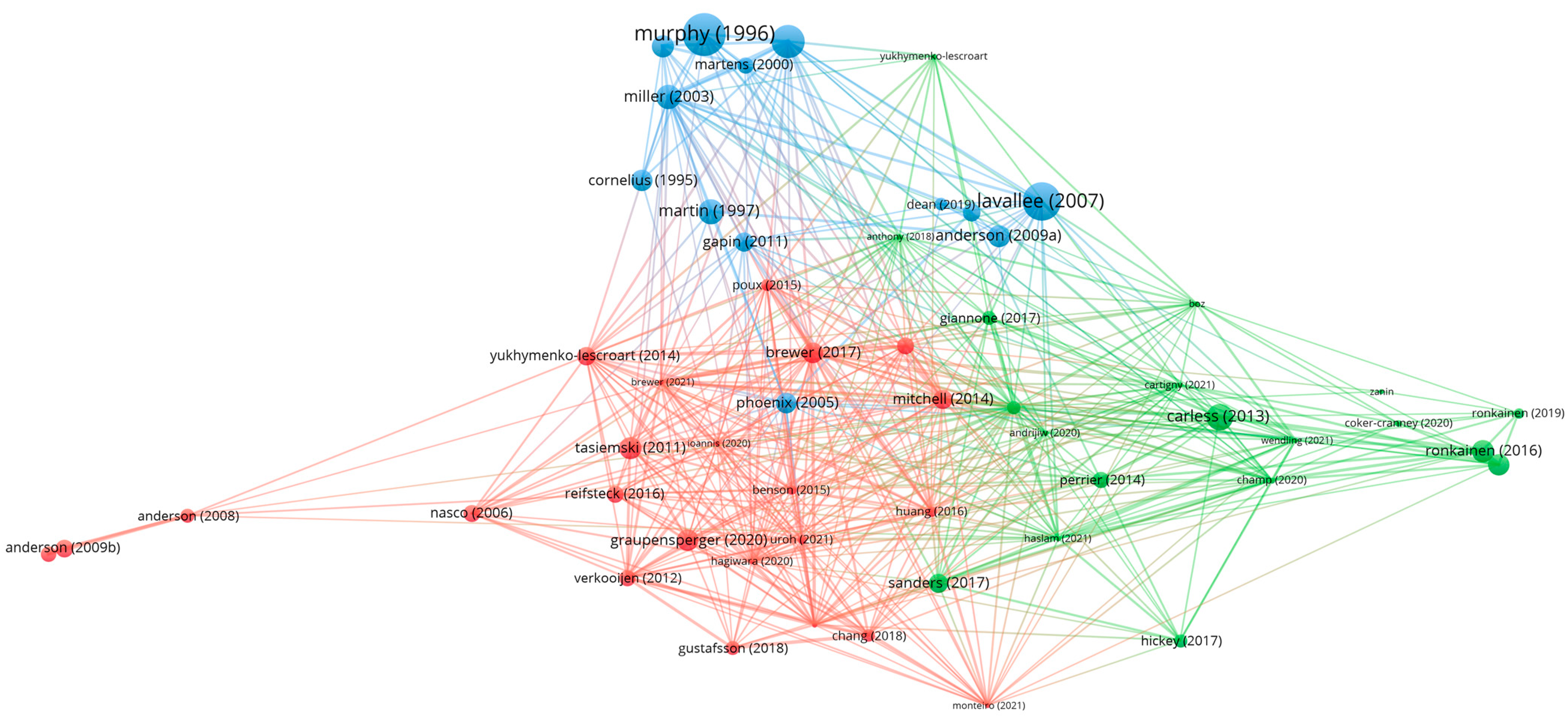

3.2. Blibliographic Coupling Analysis

3.3. Sum Code Classification Analysis

3.4. Identity Work upon Significant Life Events

3.5. Identity Work Modes

3.5.1. Cognitive Identity Work Mode

3.5.2. Discursive Identity Work Mode

3.5.3. Physical Identity Work Mode

3.5.4. Behavioral Identity Work Mode

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jones, S.R.; McEwen, M.K. A conceptual model of multiple dimensions of identity. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 2000, 41, 405–414. [Google Scholar]

- Ronkainen, N.J.; Nesti, M.S. Meaning and Spirituality in Sport and Exercise; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, J. Culture as existential territory: Ecosophic homelands for the twenty-first century. Deleuze Stud. 2012, 6, 306–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendling, E.; Flaherty, M.; Sagas, M.; Kaplanidou, K. Youth athletes’ sustained involvement in elite sport: An exploratory examination of elements affecting their athletic participation. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2018, 13, 658–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beamon, K. “I’ma baller”: Athletic identity foreclosure among African-American former student-athletes. J. Afr. Am. Stud. 2012, 16, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carless, D.; Douglas, K. “In the boat” but “selling myself short”: Stories, narratives, and identity development in elite sport. Sport Psychol. 2013, 27, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, W.; Nasco, S.; Riley, S.; Headrick, B. Athlete identity and reactions to retirement from sports. J. Sport Behav. 1998, 21, 338–362. [Google Scholar]

- Hollings, S.C.; Mallett, C.J.; Hume, P.A. The transition from elite junior track-and-field athlete to successful senior athlete: Why some do, why others don’t. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2014, 9, 457–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendling, E.O. Development and Validation of the Career Identity Development Inventory and Its Application to Former NCAA Student-Athletes; University of Florida: Gainesville, FL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cosh, S.; Crabb, S.; Tully, P.J. A champion out of the pool? A discursive exploration of two Australian Olympic swimmers’ transition from elite sport to retirement. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2015, 19, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, S.J.; Huml, M.R. The relationship between athletic identity and academic major chosen by student-athletes. Int. J. Exerc. Sci. 2017, 10, 915. [Google Scholar]

- Kerr, G.; Dacyshyn, A. The retirement experiences of elite, female gymnasts. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 2000, 12, 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryba, T.V.; Stambulova, N.B.; Selänne, H.; Aunola, K.; Nurmi, J.-E. “Sport has always been first for me” but “all my free time is spent doing homework”: Dual career styles in late adolescence. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2017, 33, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, J.C. The effect of athletic identity and locus of control on the stress perceptions of community college student-athletes. Community Coll. J. Res. Pract. 2016, 40, 729–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drahota, J.A.T.; Eitzen, D.S. The role exit of professional athletes. Sociol. Sport J. 1998, 15, 263–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gairdner, S.E. The Making and Unmaking of Elite Athletes: The Body Informed Transition out of Sport; University of Toronto: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Stephan, Y. Repercussions of transition out of elite sport on subjective well-being: A one-year study. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 2003, 15, 354–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendling, E.; Sagas, M. Is there a reformation into identity achievement for life after elite sport? A journey of identity growth paradox during liminal rites and identity moratorium. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wylleman, P.; Lavallee, D. A developmental perspective on transitions faced by athletes. Dev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. A Lifesp. Perspect. 2004, 507–527. [Google Scholar]

- Wendling, E.; Kellison, T.B.; Sagas, M. A conceptual examination of college athletes’ role conflict through the lens of conservation of resources theory. Quest 2018, 70, 28–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, M.L. Student-Athletes’ Perceptions of Their Academic and Athletic Roles: Intersections Amongst Their Athletic Role, Academic Motivation, Choice of Major, and Career Decision Making; California State University: Long Beach, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Settles, I.H.; Sellers, R.M.; Damas, A., Jr. One role or two?: The function of psychological separation in role conflict. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denny, K.G.; Steiner, H. External and internal factors influencing happiness in elite collegiate athletes. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2009, 40, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, J.J. Emerging adulthood: What is it, and what is it good for? Child Dev. Perspect. 2007, 1, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, B.W.; Van Raalte, J.L.; Linder, D.E. Athletic identity: Hercules’ muscles or Achilles heel? Int. J. Sport Psychol. 1993, 24, 237–254. [Google Scholar]

- Wittman, S. Lingering identities. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2019, 44, 724–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrier, M.J.; Smith, B.; Strachan, S.M.; Latimer, A.E. Narratives of athletic identity after acquiring a permanent physical disability. Adapt. Phys. Act. Q. 2014, 31, 106–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Killeya-Jones, L.A. Identity Structure, Role Discrepancy and Psychological Adjustment in Male College Student-Athletes. J. Sport Behav. 2005, 28, 167–185. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, P.S.; Kerr, G.A. The role experimentation of intercollegiate student athletes. Sport Psychol. 2003, 17, 196–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Harrison, S.H.; Corley, K.G. Identification in organizations: An examination of four fundamental questions. J. Manag. 2008, 34, 325–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.D. Identities and identity work in organizations. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2015, 17, 20–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caza, B.B.; Vough, H.; Puranik, H. Identity work in organizations and occupations: Definitions, theories, and pathways forward. J. Organ. Behav. 2018, 39, 889–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvesson, M.; Willmott, H. Producing the appropriate individual: Identity regulation as organizational control. J. Manag. Stud. 2002, 39, 619–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doeselaar, L.V.; Becht, A.; Klimstra, T.; Meeus, W. A review and integration of three key components of identity development. Eur. Psychol. 2018, 23, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erikson, E. Theory of identity development. In Identity and the Life Cycle; International Universities Press: New York, NY, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Ronkainen, N.J.; Kavoura, A.; Ryba, T.V. Narrative and discursive perspectives on athletic identity: Past, present, and future. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2016, 27, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stambulova, N.B.; Ryba, T.V.; Henriksen, K. Career development and transitions of athletes: The international society of sport psychology position stand revisited. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2021, 19, 524–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Welch, V.A. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009, 62, e1–e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Citation-based clustering of publications using CitNetExplorer and VOSviewer. Scientometrics 2017, 111, 1053–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallis, J.F.; Prochaska, J.J.; Taylor, W.C. A review of correlates of physical activity of children and adolescents. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2000, 32, 963–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hase, A.; O’Brien, J.; Moore, L.J.; Freeman, P. The Relationship Between Challenge and Threat States and Performance: A Systematic Review. Sport Exerc. Perform. 2019, 8, 123–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stryker, S. Identity Theory: Developments and Extensions; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Stryker, S.; Serpe, R.T. Commitment, identity salience, and role behavior: Theory and research example. In Personality, Roles, and Social Behavior; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1982; pp. 199–218. [Google Scholar]

- McCall, G.J.; Simmons, J.L. Identities and Interactions: An Examination of Human Associations in Everyday Life; Free Press: New York, NY, USA; Collier-Macmillan: Springfield, OH, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Marcia, J.E. Development and validation of ego-identity status. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1966, 3, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yukhymenko-Lescroart, M.A. Students and athletes? Development of the Academic and Athletic Identity Scale (AAIS). Sport Exerc. Perform. Psychol. 2014, 3, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.B.; Masse, L.C.; Hergenroeder, A.C. Factorial and construct validity of the athletic identity questionnaire for adolescents. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2007, 39, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelius, A. The relationship between athletic identity, peer and faculty socialization, and college student development. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 1995, 36, 560–573. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, G.M.; Petitpas, A.J.; Brewer, B.W. Identity foreclosure, athletic identity, and career maturity in intercollegiate athletes. Sport Psychol. 1996, 10, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.J.; Eklund, R.C.; Mushett, C.A. Factor structure of the athletic identity measurement scale with athletes with disabilities. Adapt. Phys. Act. Q. 1997, 14, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.; Hartley, D.L. Athletic identity and career maturity of male college student athletes. Int. J. Sport Psychol. 1998, 29, 17–26. [Google Scholar]

- Martens, M.P.; Cox, R.H. Career development in college varsity athletes. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 2000, 41, 172–180. [Google Scholar]

- Hockey, J. Injured distance runners: A case of identity work as self-help. Sociol. Sport J. 2005, 22, 38–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phoenix, C.; Faulkner, G.; Sparkes, A.C. Athletic identity and self-ageing: The dilemma of exclusivity. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2005, 6, 335–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lally, P.S.; Kerr, G.A. The career planning, athletic identity, and student role identity of intercollegiate student athletes. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2005, 76, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.L.; Glintmeyer, N.; McKenzie, A. Slim bodies, eating disorders and the coach-athlete relationship: A tale of identity creation and disruption. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2005, 40, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasco, S.A.; Webb, W.M. Toward an Expanded Measure of Athletic Identity: The Inclusion of Public and Private Dimensions. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2006, 28, 434–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavallee, D.; Robinson, H.K. In pursuit of an identity: A qualitative exploration of retirement from women’s artistic gymnastics. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2007, 8, 119–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.B.; Coleman, K.J. Adaptation and validation of the athletic identity questionnaire-adolescent for use with children. J. Phys. Act. Health 2008, 5, 539–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, C.B.; Masse, L.C.; Zhang, H.; Coleman, K.J.; Chang, S. Contribution of athletic identity to child and adolescent physical activity. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2009, 37, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, D. Adolescent Girls’ Involvement in Disability Sport: Implications for Identity Development. J. Sport Soc. Issues 2009, 33, 427–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houle, J.L.; Brewer, B.W.; Kluck, A.S. Developmental trends in athletic identity: A two-part retrospective study. J. Sport Behav. 2010, 33, 146. [Google Scholar]

- Gapin, J.I.; Petruzzello, S.J. Athletic identity and disordered eating in obligatory and non-obligatory runners. J. Sports Sci. 2011, 29, 1001–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasiemski, T.; Brewer, B.W. Athletic identity, sport participation, and psychological adjustment in people with spinal cord injury. Adapt. Phys. Act. Q. 2011, 28, 233–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinfeldt, M.; Steinfeldt, J.A. Athletic Identity and Conformity to Masculine Norms Among College Football Players. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 2012, 24, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkooijen, K.T.; van Hove, P.; Dik, G. Athletic Identity and Well-Being among Young Talented Athletes who Live at a Dutch Elite Sport Center. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 2012, 24, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, T.O.; Nesti, M.; Richardson, D.; Midgley, A.W.; Eubank, M.; Littlewood, M. Exploring athletic identity in elite-level English youth football: A cross-sectional approach. J. Sports Sci. 2014, 32, 1294–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yukhymenko-Lescroart, M.A. Sport-to-School Spillover Effects of Passion for Sport: The Role of Identity in Academic Performance. Psychol. Rep. 2021, 125, 1469–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poux, K.N.; Fry, M.D. Athletes’ Perceptions of Their Team Motivational Climate, Career Exploration and Engagement, and Athletic Identity. J. Clin. Sport Psychol. 2015, 9, 360–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reifsteck, E.J.; Gill, D.L.; Labban, J.D. “Athletes” and “exercisers”: Understanding identity, motivation, and physical activity participation in former college athletes. Sport Exerc. Perform. Psychol. 2016, 5, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, A.J.; Evans, M.B.; Surya, M.; Martin, L.J.; Eys, M.A. Embracing athletic identity in the face of threat. Sport Exerc. Perform. Psychol. 2015, 4, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-J.; Chou, C.-C.; Hung, T.-M. College experiences and career barriers among semi-professional student-athletes. Career Dev. Int. 2016, 21, 571–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, G.; Stevinson, C. Associations between retirement reasons, chronic pain, athletic identity, and depressive symptoms among former professional footballers. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2017, 17, 1311–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickey, C.; Roderick, M. The Presentation of Possible Selves in Everyday Life: The Management of Identity Among Transitioning Professional Athletes. Sociol. Sport J. 2017, 34, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannone, Z.A.; Haney, C.J.; Kealy, D.; Ogrodniczuk, J.S. Athletic identity and psychiatric symptoms following retirement from varsity sports. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2017, 63, 598–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasquinha, A.M.; Cardinal, B.J. Association of Athletic Identity by Competitive Sport Level and Cultural Popularity. J. Sport Behav. 2017, 40, 191–203. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, W.H.; Wu, C.-H.; Kuo, C.-C.; Chen, L.H. The role of athletic identity in the development of athlete burnout: The moderating role of psychological flexibility. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2018, 39, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony, C.E.; Swank, J.M. Black college student-athletes: Examining the intersection of gender, and racial identity and athletic identity. J. Study Sports Athl. Educ. 2018, 12, 179–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson, H.; Martinent, G.; Isoard-Gautheur, S.; Hassmén, P.; Guillet-Descas, E. Performance based self-esteem and athlete-identity in athlete burnout: A person-centered approach. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2018, 38, 56–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Rens, F.E.C.A.; Ashley, R.A.; Steele, A.R. Well-Being and Performance in Dual Careers: The Role of Academic and Athletic Identities. Sport Psychol. 2019, 33, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronkainen, N.J.; Ryba, T.V.; Selänne, H. “She is where I’d want to be in my career”: Youth athletes’ role models and their implications for career and identity construction. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2019, 45, 101562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, N.A. “Just Act Normal”: Concussion and the (Re)negotiation of Athletic Identity. Sociol. Sport J. 2019, 36, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proios, I. The role of dispositional factors achievement goals and volition in the formation of athletic identity people with physical disability. Phys. Act. Rev. 2020, 8, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagiwara, G. Validity and reliability evaluation of the multidimensional Japanese athletic identity measurement scale. J. Hum. Sport Exerc. 2020, 15, 380–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrijiw, A.M. Identity regulation in the North American field of men’s professional ice hockey: An examination of organizational control and preparation for athletic career retirement. Sport Manag. Rev. 2020, 23, 898–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graupensperger, S.; Benson, A.J.; Kilmer, J.R.; Evans, M.B. Social (un)distancing: Teammate interactions, athletic identity, and mental health of student-athletes during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Adolesc. Health 2020, 67, 662–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, R.; Monteiro, D.; Torregrossa, M.; Travassos, B. Career Planning in Elite Soccer: The Mediating Role of Self-Efficacy, Career Goals, and Athletic Identity. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 694868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uroh, C.C.; Adewunmi, C.M. Psychological Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Athletes. Front. Sports Act. Living 2021, 3, 603415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslam, C.; Lam, B.C.P.; Yang, J.; Steffens, N.K.; Haslam, S.A.; Cruwys, T.; Boen, F.; Mertens, N.; De Brandt, K.; Wang, X.; et al. When the final whistle blows: Social identity pathways support mental health and life satisfaction after retirement from competitive sport. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2021, 57, 102049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanin, A.C.; Martinez, L.V.; Niess, L.C. Fragmenting Feminine-Athletic Identities: Identity Turning Points During Girls’ Transition into High School. Commun. Sport 2021, 10, 767–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartigny, E.; Fletcher, D.; Coupland, C.; Bandelow, S. Typologies of dual career in sport: A cluster analysis of identity and self-efficacy. J. Sports Sci. 2021, 39, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brewer, B.W.; Caldwell, C.M.; Petitpas, A.J.; Van Raalte, J.L.; Pans, M.; Cornelius, A.E. Development and Preliminary Validation of a Sport-Specific Self-Report Measure of Identity Foreclosure. J. Clin. Sport Psychol. 2021, 15, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boz, B.; Kiremitci, O. Might “early identity maturation” be a more inclusive concept than identity foreclosure? Identity and school alienation in adolescent student athletes and non-athletes. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 42, 9780–9794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.D.; Toyoki, S. Identity work and legitimacy. Organ. Stud. 2013, 34, 875–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fachin, F.F.; Davel, E. Reconciling contradictory paths: Identity play and work in a career transition. J. Organ. Change Manag. 2015, 28, 369–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koerner, M.M. Courage as identity work: Accounts of workplace courage. Acad. Manag. J. 2014, 57, 63–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petriglieri, J.L. Co-creating relationship repair: Pathways to reconstructing destabilized organizational identification. Adm. Sci. Q. 2015, 60, 518–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frandsen, S. Portraits of Call Centre Employees: Understanding control and identity work. Tamara J. Crit. Organ. Inq. 2015, 13, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, K. Blue-collar discourses of workplace dignity: Using outgroup comparisons to construct positive identities. Manag. Commun. Q. 2011, 25, 353–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marlow, S.; McAdam, M. Incubation or induction? Gendered identity work in the context of technology business incubation. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2015, 39, 791–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvesson, M.; Lee Ashcraft, K.; Thomas, R. Identity matters: Reflections on the construction of identity scholarship in organization studies. Organization 2008, 15, 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driver, M. How trust functions in the context of identity work. Hum. Relat. 2015, 68, 899–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killian, C.; Johnson, C. “I’m Not an Immigrant!”: Resistance, Redefinition, and the Role of Resources in Identity Work. Soc. Psychol. Q. 2006, 69, 60–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.; Glastetter-Fender, C.; Shelton, M. Psychosocial identity and career control in college student-athletes. J. Vocat. Behav. 2000, 56, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Sluss, D.M.; Harrison, S.H. Socialization in Organizational Contexts; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, P.J.; Stets, J.E. Identity Theory; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Woodruff, A.L.; Schallert, D.L. Studying to play, playing to study: Nine college student-athletes’ motivational sense of self. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2008, 33, 34–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baillie, P.H. Understanding retirement from sports: Therapeutic ideas for helping athletes in transition. Couns. Psychol. 1993, 21, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grove, J.R.; Lavallee, D.; Gordon, S. Coping with retirement from sport: The influence of athletic identity. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 1997, 9, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Lavallee, D.; Tod, D. Athletes’ career transition out of sport: A systematic review. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2013, 6, 22–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willard, V.C.; Lavallee, D. Retirement experiences of elite ballet dancers: Impact of self-identity and social support. Sport Exerc. Perform. Psychol. 2016, 5, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruner, J. The narrative construction of reality. Crit. Inq. 1991, 18, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdams, D.P. Narrative identity. In Handbook of Identity Theory and Research; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 99–115. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C.; Austin, W.G.; Worchel, S. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. Organ. Identity A Read. 1979, 56, 9780203505984-16. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer, B.W.; Petitpas, A.J. Athletic identity foreclosure. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2017, 16, 118–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reifsteck, E.J.; Gill, D.L.; Brooks, D. The relationship between athletic identity and physical activity among former college athletes. Athl. Insight 2013, 5, 271–284. [Google Scholar]

- Caza, B.B.; Moss, S.; Vough, H. From synchronizing to harmonizing: The process of authenticating multiple work identities. Adm. Sci. Q. 2018, 63, 703–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramarajan, L. Past, present and future research on multiple identities: Toward an intrapersonal network approach. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2014, 8, 589–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.D. Identities in and around organizations: Towards an identity work perspective. Hum. Relat. 2022, 75, 1205–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stryker, S.; Burke, P.J. The past, present, and future of an identity theory. Soc. Psychol. Q. 2000, 63, 284–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Athletic Identity Correlates | n | k | % k Supporting Associations | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| + | − | 0 | Sum | |||

| Goal perspective | 1 | 1 | 100 | + | ||

| Volitional competency | 1 | 1 | 100 | + | ||

| Burnout | 2 | 3 | 66.6 | 33.3 | ? | |

| Academic outcomes (GPA) | 1 | 1 | 100 | − | ||

| Psychological distress | 3 | 3 | 100 | + | ||

| Gender (female) | 2 | 2 | 50 | 50 | ? | |

| Racial identity | 1 | 1 | 100 | + | ||

| Career barrier | 2 | 2 | 100 | − | ||

| College resource utilization | 1 | 1 | 100 | − | ||

| Years of participation | 1 | 1 | 100 | + | ||

| Career preparedness | 5 | 5 | 40 | 60 | ? | |

| Athletic identity foreclosure | 2 | 2 | 100 | 0 | ||

| Meaning in life | 1 | 1 | 100 | + | ||

| Perceived control | 1 | 1 | 100 | + | ||

| Motivational climate | 1 | 1 | 100 | + | ||

| Obligation towards participation | 1 | 1 | 100 | + | ||

| Eating disorder | 1 | 1 | 100 | + | ||

| Physical activity | 4 | 4 | 100 | + | ||

| Future aging of body and self | 1 | 1 | 100 | − | ||

| Conformity to masculine norms | 1 | 1 | 100 | + | ||

| Athletic self-efficacy | 1 | 1 | 100 | + | ||

| Fitness | 1 | 1 | 100 | + | ||

| Sedentary behavior | 1 | 1 | 100 | − | ||

| Social support | 1 | 1 | 100 | + | ||

| Psychological well-being | 2 | 2 | 50 | 50 | ? | |

| Rigor of chosen major | 1 | 1 | 100 | − | ||

| Sport participation level | 2 | 2 | 100 | + | ||

| Cultural popularity of sport | 1 | 1 | 100 | + | ||

| Living conditions | 1 | 1 | 100 | 0 | ||

| Sport participation | 3 | 3 | 100 | + | ||

| Vocational identity | 1 | 1 | 100 | 0 | ||

| Life management | 1 | 1 | 100 | − | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chun, Y.; Wendling, E.; Sagas, M. Identity Work in Athletes: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Sports 2023, 11, 203. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports11100203

Chun Y, Wendling E, Sagas M. Identity Work in Athletes: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Sports. 2023; 11(10):203. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports11100203

Chicago/Turabian StyleChun, Yoonki, Elodie Wendling, and Michael Sagas. 2023. "Identity Work in Athletes: A Systematic Review of the Literature" Sports 11, no. 10: 203. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports11100203

APA StyleChun, Y., Wendling, E., & Sagas, M. (2023). Identity Work in Athletes: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Sports, 11(10), 203. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports11100203