Next-Generation Precision Breeding in Peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) for Disease and Pest Resistance: From Multi-Omics to AI-Driven Innovations

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Current Understanding of Peanut–Pathogen–Pest Interactions

2.1. Major Diseases and Their Impact

2.1.1. Early and Late Leaf Spot (Cercospora arachidicola, C. personatum)

2.1.2. Rust (Puccinia arachidis)

2.1.3. Aflatoxin Contamination (Aspergillus flavus, A. parasiticus)

2.1.4. Bacterial Wilt (Ralstonia solanacearum)

2.1.5. The Root-Knot Nematode (RKN) (Meloidogyne arenaria)

| Types | Pathogen | Diseases | Symptoms | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial | Ralstonia solanacearum | Bacterial wilt | Rapid wilting of the plant leading to eventual death. | [45,46] |

| Fungal | Nothopassalora personata | Late leaf spot (LLS) | Dark brown to black lesions on leaves, rapid defoliation | [14] |

| Cercospora arachidicola | Early leaf spot (ELS)/Cercospora leaf spot (CLS) | Causes circular or irregular leaf lesions surrounded by yellow halos | [47] | |

| Pythium myriotylum/Rhizoctonia solani | Pod rot | Pods become soft, mushy, or shrivelled with discoloured kernels, leading to pod rot and damaged peanuts. | [48] | |

| Aspergillus flavus/Aspergillus parasiticus | Aflatoxin contamination | Moldy seeds/potential aflatoxin contamination | [49,50] | |

| Scelrotium rolfsii | Stem rot | Mycelium covers the stem near the soil surface, with sclerotia formation on diseased tissue. | [51,52] | |

| Viral | Groundnut rosette assistor virus (GRAV) | Groundnut rosette disease (GRD) | Mosaic patterns or necrotic lesions on leaves, severe stunting, shortened internodes, and reduced leaf size. | [53] |

| Groundnut bud necrosis virus | Peanut stem necrosis disease (PSND) | Necrotic spots and streaks on stem, petiole, and buds, chlorotic mottling on leaves, stunting, and proliferation of axillary shoots. | [54,55] |

2.2. Major Insect Pests of Peanut: Dynamics, Damage, and Global Impact

2.2.1. Sucking Pests and Defoliators

Groundnut Aphids (Aphis craccivora)

Groundnut Pod Borer (Helicoverpa armigera)

Spodoptera litura

Root and Pod Feeders

2.2.2. Storage Insect Pests: Hidden Post-Harvest Losses

| Insect Pests | Mode of Damage | References |

|---|---|---|

| Tobacco thrips (Frankliniella fusca) | Thrips feed on developing leaves and buds using rasng-sucking mouthparts, causing leaf discoloration, distortion, and stunting. | [70] |

| Groundnut bruchid (Caryedon serratus) | Larvae bore into seeds and feed on embryo and endosperm, creating exit holes and reducing seed weight, quality, and nutritive value. | [71] |

| Tobacco caterpillar (S. litura) | Larvae feed on leaf undersides, skeletonizing and destroying leaves, leaving only petioles and branches. | [72] |

| Cotton bollworm (H. armigera) | Larvae feed on leaf tissue, leaf edges, and flower buds, potentially destroying all new buds and severely reducing yield. | [73] |

|

Black cutworm

(Agrotis ipsilon) | Larvae cut tender stems and roots, killing plants, and burrow into pods to feed on kernels. | [73] |

| Groundnut leafminer (Aproaerema modicella) | Larvae feed on leaves, reducing photosynthetic area and lowering yield. | [74,75] |

|

White grubs

(Holotrichia parallela) | White grubs feed on roots, seeds, tubers, and pods underground, causing kernel and pod damage and reducing yield. | [76,77] |

| Groundnut sucking bug (Rhyparochromus litotoralis) | Bugs perforate pods and feed on seeds, causing shrivelling, increased free fatty acids, rancid flavour, and reduced kernel quality. | [78] |

| Groundnut pod borer (Elasmolomus sordidus) | Sucking activity deforms kernels, making them unfit for human and animal consumption. | [79] |

|

Thrips

(Scirtothrips dorsalis) | Transmit PYSV, causing yellow chlorotic spots and patches, leaf curling, necrosis, stunted growth, and eventual plant death. | [80,81] |

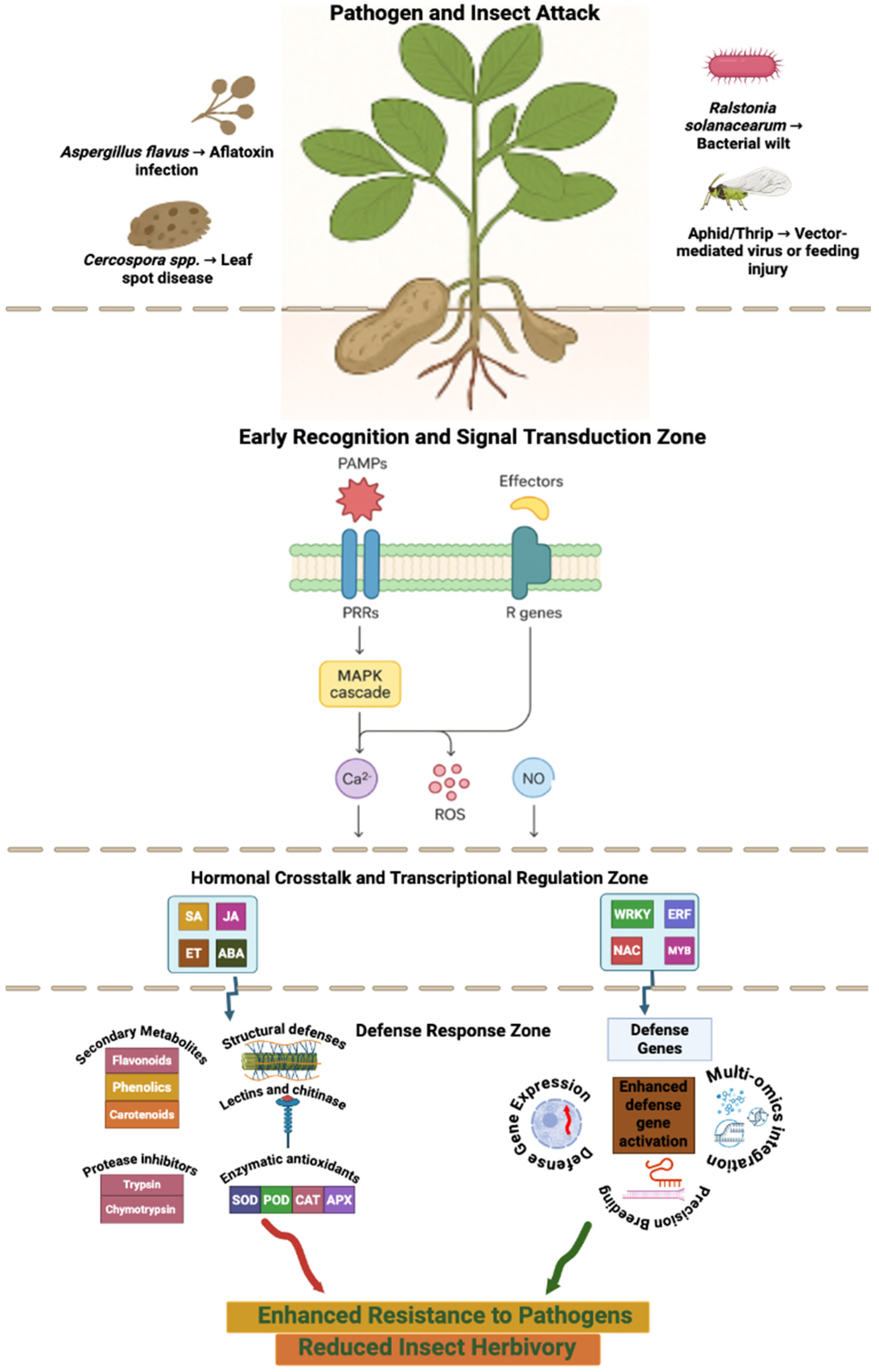

3. Host Defense Mechanisms: Molecular, Biochemical, and Cellular Layers

3.1. Multi-Layered Plant Defense Architecture

3.2. Early Signalling and Oxidative Dynamics

3.3. Inducible Defense Proteins and PR Gene Families

3.4. Hormonal Cross-Talk in Defense Regulation

4. Traditional Approaches to Disease and Pest Management in Peanut

4.1. Cultural Practices: The Cornerstone of Traditional Management

4.2. Biological Control: Harnessing the Microbial Arsenal

4.3. Chemical Control: The Reactive Pillar of Conventional Management

5. Precision Breeding Tools for Peanut Disease and Insect Resistance

| Technology/Tool | Application | Target Trait | Key Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marker-Assisted Selection (MAS) | Use trait-linked markers to introgressed or pyramid alleles (e.g., backcrossing high-oleic alleles or nematode/leaf-spot resistance QTLs into elite varieties) | High-oleic oil (AhFAD2), nematode resistance, major disease QTLs | Rapid introgression of single/few major loci with minimal linkage drag; proved route for high-oleic and specific resistance traits. | [113] |

| Genomic Selection (GS) | Genomic prediction models trained on marker panels to predict breeding values and select lines before phenotyping | Complex, polygenic traits such as quantitative disease tolerance, yield under stress | Improves selection accuracy and cycle time for complex traits; promising early results in peanut with ongoing methodological development. | [114] |

| Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS)/QTL Mapping | Scan diverse panels to find marker–trait associations and candidate genes for resistance | Late leaf spot, rust, other foliar diseases; putative NLR and PR proteins | Identifies loci and candidate genes (MQTLs) for downstream MAS, candidate gene validation, and genomic prediction. | [114] |

| CRISPR/Cas (Including Base Editors, Cas12a) | Targeted gene knock-out/knock-in or base editing (nutritional traits, virulence/host susceptibility genes, allergen reduction) | Candidate defense regulators (e.g., transcription factors), allergen genes, metabolic genes (AhFAD2 edits for oil quality) | Enables precise, targeted edits to validate gene function and create improved alleles (proof-of-concept demonstrated in peanut; hairy-root and tissue systems used). | [115] |

| RNA Interference (RNAI)/Host-Induced Gene Silencing (HIGS) | Silencing of pest or pathogen genes (or host susceptibility genes) using transgenic or topical RNA approaches | Insect pests (thrips, caterpillars), fungal virulence factors | Demonstrated reductions in pest/pathogen impact in experimental systems; useful for functional validation and targeted control strategies. | [116] |

| High-Throughput Phenomics (UAVS, Multispectral/Hyperspectral Sensors) | UAV/RGB/multispectral imaging and automated pipelines to measure canopy traits, NDVI, canopy temperature, LAI and stress signatures | Symptom severity for foliar diseases (late leaf spot), canopy vigor under pest/disease pressure, drought interactions | Rapid, repeatable field phenotyping that discriminates genotypes and supports downstream GWAS/GS/AI models. | [117] |

| Artificial Intelligence/Machine Learning (CNNS, RF, XAI) | Image processing, feature extraction, predictive models integrating phenomics, envirotyping and genomics for resistance prediction | Binary or probabilistic resistance classification; ranking breeding lines for advancement | Converts complex, multi-source data into actionable resistance scores and breeder decision support; improves selection efficiency when coupled with HTP. | [118] |

5.1. Marker-Assisted Selection for Polygenic Resistance Traits in Peanut

5.2. Genome-Wide Association Study (GWAS) for Dissecting Resistance Traits in Peanut

5.3. High-Throughput Phenotyping in Peanut

| Category | Crop/Species | Gene/Marker | Trait Improved | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAS | Oryza sativa | Pi9 + Pi54 functional markers | Blast disease resistance | [136] |

| MAS | Oryza sativa | Gn1a and other major QTLs | Grain number and yield | [137] |

| MAS | Triticum aestivum | TaGW2, TaSus1 | Grain weight/quality | [138,139] |

| GENOME EDITING | Zea mays | ARGOS8 (CRISPR-generated variant) | Enhanced yield under stress | [140] |

| GENOME EDITING | Oryza sativa | OsERF922 (CRISPR/Cas9) | Resistance to Magnaporthe oryzae (Rice blast) | [141] |

| GENOME EDITING | Oryza sativa | IPA1, GS3, DEP1, Gn1a (CRISPR/Cas9) | Yield, panicle architecture | [142] |

| GENOME EDITING | Glycine max | FAD2-1A and FAD2-1B (CRISPR/Cas9) | Increased oleic acid (oil quality) | [143] |

| GENOME EDITING | Solanum lycopersicum | SlIAA9 (CRISPR/Cas9) | Fruit quality/seed lessness | [144] |

| Genome Editing | Cucumis sativus | eIF4E (CRISPR/Cas9) | Resistance to Cucumber vein yellowing virus (Ipomovirus) | [145] |

| Genome Editing | Glycine max | GmPDCT (CRISPR/Cas9) | Oil quality (fatty acid profile) | [146] |

| Genome Editing | Glycine max | GmTAP1 (CRISPR/Cas9) | Root rot resistance | [147] |

| Genome Editing | Solanum lycopersicum | SlMLO1 (CRISPR/Cas9) | Powdery mildew resistance caused by Oidium neolycopersici | [148] |

| Genome Editing | Hordeum vulgare | Barley MLO (CRISPR/Cas9) | Powdery mildew resistance | [149] |

| Genome Editing | Solanum lycopersicum | Pmr4 (CRISPR/Cas9) | Powdery mildew resistance | [150] |

| Genome Editing | Citrus sinensis | CsLOB1 (CRISPR/Cas9) | Resistance to citrus canker | [151,152] |

| Genome Editing | Musa spp. | RGA2, Ced9 (CRISPR/Cas9) | Resistance to Fusarium wilt | [153] |

| Genome Editing | Grape vine | VvWRKY52 (CRISPR/Cas9) | Resistance to B. cinerea | [154] |

| Genome Editing | Solanum tuberosum L. | StSR4 | Resistance to P. infestans | [155] |

| Genome Editing | Capsicum annuum | CaERF28 | Resistance to Anthracnose disease | [156] |

| Genome Editing | S. tuberosum L. | Nib, CI, CP, and P3 conserved viral regions (CRISPR/Cas13a) | Resistance to Potato virus Y | [157] |

| Genome Editing | Brassica napus | BnCRT1a | Resistance to Verticillium longisporum (Vl43) | [158] |

6. Advances in Disease and Insect Resistance Breeding

6.1. Genetic Engineering Strategies for Peanut Disease and Insect Resistance

6.2. CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Gene Editing for Disease and Insect Resistance

6.2.1. CRISPR/Cas9 Applications in Plant Disease Resistance and Pathogen Detection

6.2.2. CRISPR/Cas9 Strategies for Insect Resistance Management

6.2.3. CRISPR/Cas-Mediated Crop-Level Innovations for Insect Resistance

6.2.4. Viral Vector-Mediated Delivery of CRISPR Components in Plants

6.2.5. Nanotechnology-Assisted Delivery of Genome Editing in Biotic Stresses

7. AI-Driven Remote Sensing for Smart Disease Surveillance in Peanut

8. Multi-Omics Integration for Deciphering Disease Resistance Mechanisms in Peanut

8.1. Systems-Level Multi-Omics Insights into Foliar and Soil-Borne Disease Resistance in Peanut

8.2. Multi-Omics Regulation of Aspergillus flavus Resistance and Aflatoxin Defense Networks in Peanut

9. Challenges and Future Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, W.; Yoo, E.; Lee, S.; Sung, J.; Noh, H.J.; Hwang, S.J.; Desta, K.T.; Lee, G.-A. Seed weight and genotype influence the total oil content and fatty acid composition of peanut seeds. Foods 2022, 11, 3463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, M.; Kim, J.; Ahn, S.M. Factors associated with frequency of peanut consumption in Korea: A national population-based study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settaluri, V.; Kandala, C.; Puppala, N.; Sundaram, J. Peanuts and their nutritional aspects—A review. Food Nutr. Sci. 2012, 3, 1644–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Variath, M.T.; Janila, P. Economic and academic importance of peanut. In The Peanut Genome; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 7–26. [Google Scholar]

- Okoth, S. Incidence of insect pests in groundnut (Arachis hypogaea) fields and storage in karachuonyo and nyakach constituencies of western Kenya. Afr. J. Food Agric. Nutr. Dev. 2025, 25, 25639–25660. [Google Scholar]

- Boshou, L. A review on progress and prospects of peanut industry in China. Chin. J. Oil Crop Sci. 2020, 42, 161–166. [Google Scholar]

- Essandoh, D.A.; Odong, T.; Okello, D.K.; Fonceka, D.; Nguepjop, J.; Sambou, A.; Ballén-Taborda, C.; Chavarro, C.; Bertioli, D.J.; Leal-Bertioli, S.C. Quantitative trait analysis shows the potential for alleles from the wild species Arachis batizocoi and A. duranensis to improve groundnut disease resistance and yield in East Africa. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakya, A.; Dwivedi, R.; Kumar, S.; Raj, A.; Prakash, A. Population dynamics of aphid, Aphis craccivora Koch during kharif season on groundnut in relation to abiotic factors. Pharma Innov. J. 2021, 10, 107–111. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Kabana, R.; Williams, J.; Shelby, R. Assessment of peanut yield losses caused by Meloidogyne arenaria. Nematropica 1982, 12, 279–288. [Google Scholar]

- Tay, W.T.; Soria, M.F.; Walsh, T.; Thomazoni, D.; Silvie, P.; Behere, G.T.; Anderson, C.; Downes, S. A brave new world for an old world pest: Helicoverpa armigera (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in Brazil. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e80134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, M.R.; Gowda, M. Mechanisms of resistance to tobacco cutworm (Spodoptera litura F.) and their implications to screening for resistance in groundnut. Euphytica 2006, 149, 387–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswal, A.K.; Ozias-Akins, P.; Holbrook, C.C. Recent Technological Advancements for Identifying and Exploiting Novel Sources of Pest and Disease Resistance for Peanut Improvement. Agronomy 2024, 14, 3071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Li, H.; Gao, C.; Yu, W.; Zhang, S. Advances in omics research on peanut response to biotic stresses. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1101994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giordano, D.F.; Pastor, N.; Palacios, S.; Oddino, C.M.; Torres, A.M. Peanut leaf spot caused by Nothopassalora personata. Trop. Plant Pathol. 2021, 46, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuong, N.V.; Tri, T.L. Enhancing soil fertilizer and peanut output by utilizing endophytic bacteria and vermicompost on arsenic-contaminated soil. Int. J. Agric. Biosci. 2024, 13, 596–602. [Google Scholar]

- Van Chuong, N.; Trang, N.N.; Liem, T.T.; Dang, P.T. Effect of Bacillus sonklengsis Associated with Cattle Manure Fertilization on the Farmland Health and Peanut Yield. Int. J. Agric. Biosci. 2025, 14, 629–636. [Google Scholar]

- Möhring, N.; Ba, M.N.; Braga, A.R.C.; Gaba, S.; Gagic, V.; Kudsk, P.; Larsen, A.; Mesnage, R.; Niggli, U.; Qaim, M. Expected effects of a global transformation of agricultural pest management. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 10901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Li, M.; Achal, V. A comprehensive review on environmental and human health impacts of chemical pesticide usage. Emerg. Contam. 2025, 11, 100410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washim, M.; Manda, P.; Das, R. Pesticide resistance in insects: Challenges and sustainable solutions for modern agriculture. Int. J. Agric. Food Sci. 2024, 6, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kona, P.; Sangh, C.; Ravikiran, K.; Ajay, B.; Kumar, N. Genetic and Genomic Resource to Augment Breeding Strategies for Biotic Stresses in Groundnut. In Genomics-Aided Breeding Strategies for Biotic Stress in Grain Legumes; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 359–403. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, J.; Boiça, A., Jr.; Fernandes, O. Biology, ecology, and management of rednecked peanutworm (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae). J. Integr. Pest Manag. 2020, 11, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Juheishy, W.K.; Ghazal, S.A. Role of nano-fertilizers in improving productivity of peanut crop: A Review. Mesop. J. Agric. 2023, 51, 13–27. [Google Scholar]

- Rudrapal, M.; Rakshit, G.; Singh, R.P.; Garse, S.; Khan, J.; Chakraborty, S. Dietary polyphenols: Review on chemistry/sources, bioavailability/metabolism, antioxidant effects, and their role in disease management. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales, M.; Kemerait, R., Jr.; Bertioli, D.; Leal-Bertioli, S. Strong resistance to early and late leaf spot in peanut-compatible wild-derived induced allotetraploids. Plant Dis. 2023, 107, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLaughlin, D.J.; Spatafora, J.W. Systematics and Evolution: Part A; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- Mondal, S.; Badigannavar, A. Peanut rust (Puccinia arachidis Speg.) disease: Its background and recent accomplishments towards disease resistance breeding. Protoplasma 2015, 252, 1409–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daudi, H.; Shimelis, H.; Mwadzingeni, L.; Laing, M.; Okori, P. Breeding groundnut for rust resistance: A review. Legume Res. (TSI) 2019, 42, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, I.; Tillman, B.; Brenneman, T.; Kemerait, R.; Stevenson, K.L.; Culbreath, A. Field evaluation and components of peanut rust resistance of newly developed breeding lines. Peanut Sci. 2019, 46, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinson, C.; Antepenko, E.; Leal-Bertioli, S.; Chu, Y.; Culbreath, A.; Stalker, H.; Gao, D.; Ozias-Akins, P. Resistance to rust (Puccinia arachidis Speg.) identified in nascent allotetraploids cross-compatible with cultivated peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.). Peanut Sci. 2021, 48, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khlangwiset, P.; Wu, F. Costs and efficacy of public health interventions to reduce aflatoxin-induced human disease. Food Addit. Contam. 2010, 27, 998–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neira-Mosquera, J.A.; Sánchez-Llaguno, S.N.; Aldas-Morejon, J.P.; Revilla-Escobar, K.Y.; Morán-Estrella, M.C.; Josenkha, M. Aflatoxin Contents and Bromatological Quality in Two Varieties of Peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) in Different States and Storage Systems in Ecuador. Int. J. Agric. Biosci. 2025, 14, 1042–1049. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, P.C.; Moore, S.E.; Hall, A.J.; Prentice, A.M.; Wild, C.P. Modification of immune function through exposure to dietary aflatoxin in Gambian children. Environ. Health Perspect. 2003, 111, 217–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerre, P. Worldwide mycotoxins exposure in pig and poultry feed formulations. Toxins 2016, 8, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, E.; Dong, H.; Hou, H.; Zhang, Z.; Ji, N.; Ma, W. Factors influencing aflatoxin contamination in before and after harvest peanuts: A review. J. Food Res. 2015, 4, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ncube, J.; Maphosa, M. Current state of knowledge on groundnut aflatoxins and their management from a plant breeding perspective: Lessons for Africa. Sci. Afr. 2020, 7, e00264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Pandey, M.K.; Zhi, Y.; Zhang, H.; Xu, S.; Guo, J.; Wu, B.; Chen, H.; Ren, X.; Zhou, X. Discovery of two novel and adjacent QTLs on chromosome B02 controlling resistance against bacterial wilt in peanut variety Zhonghua 6. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2020, 133, 1133–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H.; Ren, X.; Liao, B. Genetic diversity of peanut genotypes with resistance to bacterial wilt based on seed characters. Chin. J. Oil Crop Sci. 2006, 28, 144. [Google Scholar]

- Yong, L.; Shengyu, W.; Dong, L.; Huifang, J.; Boshou, L. Evaluation of resistance to aflatoxin production among peanut germplasm with resistance to bacterial wilt. Zhongguo You Liao Zuo Wu Xue Bao = Chin. J. Oil Crop Sci. 2004, 26, 69–71. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, W. Research progress of peanut bacterial wilt in China. Chin. J. Oil Crop Sci. 2022, 44, 1159–1165. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, B.; Jiang, H.; Liao, B.; Ren, X. Progress on groundnut genetic enhancement for bacterial wilt resistance. Chin. Agric. Sci. Bull 2007, 23, 369–372. [Google Scholar]

- Osman, H.A.; Ameen, H.H.; Mohamed, M.; Elkelany, U.S. Efficacy of integrated microorganisms in controlling root-knot nematode Meloidogyne javanica infecting peanut plants under field conditions. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2020, 44, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Holbrook, C.C.; Timper, P.; Brenneman, T.B.; Mullinix, B.G. Comparison of methods for assessing resistance to Meloidogyne arenaria in peanut. J. Nematol. 2007, 39, 169. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, J.T.; Haegeman, A.; Danchin, E.G.; Gaur, H.S.; Helder, J.; Jones, M.G.; Kikuchi, T.; Manzanilla-López, R.; Palomares-Rius, J.E.; Wesemael, W.M. Top 10 plant-parasitic nematodes in molecular plant pathology. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2013, 14, 946–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timper, P.; Dickson, D.W.; Steenkamp, S. Nematode parasites of groundnut. In Plant Parasitic Nematodes in Subtropical and Tropical Agriculture; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2018; pp. 411–445. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Liang, G. Control efficacy of an endophytic Bacillus amyloliquefaciens strain BZ6-1 against peanut bacterial wilt, Ralstonia solanacearum. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 465435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Tang, H.; Yang, D.; Huang, J.; Wu, Y.; Yu, J.; Chen, J.; Wang, Q.; Yang, R.; Wan, X. Comparative genome analysis of two peanut Ralstonia solanacearum strains with significant difference in pathogenicity reveals 16S rRNA dimethyltransferase RsmA involved in inducing immunity. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2024, 11, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Pei, X.; Liang, C. Simulation of Suitable Distribution and Differentiation in Local Environments of Cercospora arachidicola in China. Agronomy 2025, 15, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, T.A.; Russell, S.A.; Anderson, M.G.; Serrato-Diaz, L.M.; French-Monar, R.D.; Woodward, J.E. Management of peanut pod rot I: Disease dynamics and sampling. Crop Prot. 2016, 79, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Song, W.; Chen, Y.; Kang, Y.; Lei, Y.; Huai, D.; Wang, Z.; Wang, X.; Liao, B. Effect of non-aflatoxigenic strains of Aspergillus flavus on aflatoxin contamination of pre-harvest peanuts in fields in China. Oil Crop Sci. 2021, 6, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adithya, G. Effect of Aspergillus flavus on Groundnut Seed Quality and Its Management; Professor Jayashankar Telangana State Agricultural University: Hyderabad, India, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Meena, P.N.; Meena, A.K.; Tiwari, R.K.; Lal, M.K.; Kumar, R. Biological Control of Stem Rot of Groundnut Induced by Sclerotium rolfsii sacc. Pathogens 2024, 13, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safari Motlagh, M.R.; Farokhzad, M.; Kaviani, B.; Kulus, D. Endophytic Fungi as Potential Biocontrol Agents against Sclerotium rolfsii Sacc.—The Causal Agent of Peanut White Stem Rot Disease. Cells 2022, 11, 2643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appiah, A.; Tegg, R.; Offei, S.; Wilson, C. Impact of groundnut rosette disease on nutritive value and elemental composition of four varieties of peanut (Arachis hypogaea). Ann. Appl. Biol. 2016, 168, 400–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TEJASWINI, P. Studies on Viral Diseases Infecting Groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.). Master’s Thesis, Acharya N. G. Ranga Agricultural University, Guntur, India, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Karthikeyan, G.; Manoranjitham, S. Ground nut (Peanut). In Viral Diseases of Field and Horticultural Crops; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 163–170. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, D.L.; Buol, G.S.; Brandenburg, R.L.; Reisig, D.; Nboyine, J.; Abudulai, M.; Oteng-Frimpong, R.; Brandford Mochiah, M.; Asibuo, J.Y.; Arthur, S. Examples of risk tools for pests in Peanut (Arachis hypogaea) developed for five countries using Microsoft Excel. J. Integr. Pest Manag. 2022, 13, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anitha, V.; Rogers, D.; Wightman, J.; Ward, A. Distribution and abundance of white grubs (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae) on groundnut in southern India. Crop Prot. 2006, 25, 732–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, G. Insect pests of groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.), nature of damage and succession with the crop stages. Bangladesh J. Agric. Res. 2014, 39, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buthelezi, M.N.; Conlong, D.E.; Zharare, G.E. Review of the biosystematics and bio-ecology of the groundnut/soya bean leaf miner species (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae). Austral Entomol. 2021, 60, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parthiban, P.; Chinniah, C.; Kalyanasundaram, M.; Baskaran, R.M.; Swaminathan, C.; Kannan, P. Influence of inter-cropping system to minimise the defoliators incidence in groundnut (Arachis hypogaea Linnaeus). Ann. Plant Prot. Sci. 2016, 24, 78–82. [Google Scholar]

- Blackman, R.; Eastop, V. Taxonimic issues. In Aphids as Crop Pest; van Emden, H.F., Harrington, R., Eds.; Cabi Publishing: Wallingford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Blount, A.; Pittman, R.; Smith, B.; Morgan, R.; Dankers, W.; Sprenkel, R.; Momol, M. First report of peanut stunt virus in perennial peanut in north Florida and southern Georgia. Plant Dis. 2002, 86, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pratissoli, D.; Lima, V.L.; Pirovani, V.D.; Lima, W.L. Occurrence of Helicoverpa armigera (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) on tomato in the Espírito Santo state. Hortic. Bras. 2015, 33, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twine, P.; Zalucki, M. A Review of Heliothis Research in Australia. In Proceedings of the Conference and Workshop Series (Queensland. Department of Primary Industries), Bribie Island, Australia, 15 August 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasa Rao, M.; Manimanjari, D.; Vanaja, M.; Rama Rao, C.; Srinivas, K.; Rao, V.; Venkateswarlu, B.; Jay, R. Impact of elevated CO2 on tobacco caterpillar, Spodoptera litura on peanut, Arachis hypogea. J. Insect Sci. 2012, 12, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, M.; Smitha, M.; Najitha, U. Root mealybugs and their management in horticultural crops in India. Pest Manag. Hortic. Ecosyst. 2016, 22, 103–113. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, S.M.; Vijayalakshmi, K.; Durga Rani, V.; Ameer Basha, S.; Srinivas, C. Survey on major insect pests of groundnut in Southern Telangana zone. Pharma Innov. J. 2021, 10, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nukenine, E. Stored product protection in Africa: Past, present and future. Julius-Kühn-Archiv 2010, 425, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Parfitt, J.; Croker, T.; Brockhaus, A. Global food loss and waste in primary production: A reassessment of its scale and significance. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandenburg, R.; Royals, B.; Taylor, S.; Malone, S.; Jordan, D.; Hare, A. Responses of tobacco thrips and peanut to imidacloprid and fluopyram. Crop Forage Turfgrass Manag. 2021, 7, e20116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreedhar, M.; Singh, D.; Reddy, D.C.; Vasudha, A. Biochemical changes in groundnut pods due to infestation of bruchid Caryedon serratus (Olivier) under stored conditions. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2020, 88, 101678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudhatra, M.C.; Bharadiya, A.; Makani, J.D.; Barad, B.D. Screening of Groundnut Genotypes against Spodoptera litura (Fab.) with Respect to Leaf Damage. Adv. Res. Teach. 2024, 25, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; He, L.; Wang, T.; Xiao, T.; Zou, Z.; Wang, M.; Cai, X.; Yao, B.; Yang, Y.; Wu, K. The effectiveness of mixed food attractant for managing Helicoverpa armigera (Hübner) and Agrotis ipsilon (Hufnagel) in peanut fields. Agronomy 2024, 14, 986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanower, T.; Wightman, J.; Gutierrez, A. Biology and control of the groundnut leafminer, Aproaerema modicella (Deventer)(Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae). Crop Prot. 1993, 12, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenis, M.; Cugala, D. Prospects for the biological control of the groundnut leaf miner, Aproaerema modicella, in Africa. CABI Rev. 2006, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Li, G.; Yan, X.; Yuan, H. Controlled release study on microencapsulated mixture of fipronil and chlorpyrifos for the management of white grubs (Holotrichia parallela) in peanuts (Arachis hypogaea L.). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 10632–10637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Nong, X.Q.; Liu, C.Q.; Xi, G.C.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Z.H. Biocontrol of peanut white grubs, Holotrichia parallela, using entomopathogenic fungus Metarhizium anisopliae at sowing period of peanut. Chin. J. Biol. Control. 2011, 27, 485. [Google Scholar]

- Samaila, A.; Malgwi, A. Biology of the Groundnut Sucking Bug (Rhyparochromus Littoralis Dist.) (Heteroptera: Lygaeidae) On Groundnut in Yola, Adamawa State–Nigeria. IOSR J. Agric. Vet. Sci. (IOSR-JAVS) 2012, 1, 53–57. [Google Scholar]

- Naawe, E.K.; Angyiereyiri, E.D. Effect and infestation levels of groundnut pod borer (Elasmolomus sordidus) on groundnut (Arachis hypogaea) and farm control measures in Tedema, Builsa-North District of the Upper East Region, Ghana. Int. J. Trop. Insect Sci. 2020, 40, 687–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopal, K.; Krishna Reddy, M.; Reddy, D.; Muniyappa, V. Transmission of peanut yellow spot virus (PYSV) by thrips, Scirtothrips dorsalis Hood in groundnut. Arch. Phytopathol. Plant Prot. 2010, 43, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudramuni, T.; Thippaiah, M.; Onkarappa, S.; Ganige, P. Screening and biochemical analysis of groundnut genotypes against thrips, Scirtothrips dorsalis Hood. J. Exp. Zool. India 2022, 25, 1761. [Google Scholar]

- Lamers, J.; Van Der Meer, T.; Testerink, C. How plants sense and respond to stressful environments. Plant Physiol. 2020, 182, 1624–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saijo, Y.; Loo, E.P.I. Plant immunity in signal integration between biotic and abiotic stress responses. New Phytol. 2020, 225, 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muthamilarasan, M.; Prasad, M. Plant innate immunity: An updated insight into defense mechanism. J. Biosci. 2013, 38, 433–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zipfel, C. Plant pattern-recognition receptors. Trends Immunol. 2014, 35, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couto, D.; Zipfel, C. Regulation of pattern recognition receptor signalling in plants. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 16, 537–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngou, B.P.M.; Ahn, H.-K.; Ding, P.; Jones, J.D. Mutual potentiation of plant immunity by cell-surface and intracellular receptors. Nature 2021, 592, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foyer, C.H. Reactive oxygen species, oxidative signaling and the regulation of photosynthesis. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2018, 154, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S.N.; Agarwal, G.; Pandey, M.K.; Sudini, H.K.; Jayale, A.S.; Purohit, S.; Desai, A.; Wan, L.; Guo, B.; Liao, B. Aspergillus flavus infection triggered immune responses and host-pathogen cross-talks in groundnut during in-vitro seed colonization. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 9659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Ma, M.; Li, Z.; Chen, X.; Zeng, J.; Huang, M.; Yin, Y.; Ran, X.; Li, J.; Le, T. Exploration of cobalt-based colorimetric aptasensing of zearalenone in cereal products: Enhanced performance of Au/CoOOH nanozyme. LWT 2025, 223, 117700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mierziak, J.; Kostyn, K.; Kulma, A. Flavonoids as important molecules of plant interactions with the environment. Molecules 2014, 19, 16240–16265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, S.; Ganai, B.A.; Kamili, A.N.; Bhat, A.A.; Mir, Z.A.; Bhat, J.A.; Tyagi, A.; Islam, S.T.; Mushtaq, M.; Yadav, P. Pathogenesis-related proteins and peptides as promising tools for engineering plants with multiple stress tolerance. Microbiol. Res. 2018, 212, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Loon, L.C.; Rep, M.; Pieterse, C.M. Significance of inducible defense-related proteins in infected plants. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2006, 44, 135–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, K.; Bhatnagar-Mathur, P.; Waliyar, F.; Sharma, K.K. Overexpression of a chitinase gene in transgenic peanut confers enhanced resistance to major soil borne and foliar fungal pathogens. J. Plant Biochem. Biotechnol. 2013, 22, 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vleesschauwer, D.; Xu, J.; Höfte, M. Making sense of hormone-mediated defense networking: From rice to Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.Q.; Dong, X. Systemic acquired resistance: Turning local infection into global defense. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2013, 64, 839–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- War, A.R.; Paulraj, M.G.; War, M.Y.; Ignacimuthu, S. Jasmonic acid-mediated-induced resistance in groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.) against Helicoverpa armigera (Hubner) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). J. Plant Growth Regul. 2011, 30, 512–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimaraes, P.M.; Guimaraes, L.A.; Morgante, C.V.; Silva, O.B., Jr.; Araujo, A.C.G.; Martins, A.C.; Saraiva, M.A.; Oliveira, T.N.; Togawa, R.C.; Leal-Bertioli, S.C. Root transcriptome analysis of wild peanut reveals candidate genes for nematode resistance. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0140937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ku, Y.-S.; Sintaha, M.; Cheung, M.-Y.; Lam, H.-M. Plant hormone signaling crosstalks between biotic and abiotic stress responses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Duan, G.; Li, C.; Liu, L.; Han, G.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, C. The crosstalks between jasmonic acid and other plant hormone signaling highlight the involvement of jasmonic acid as a core component in plant response to biotic and abiotic stresses. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fry, W.E. Principles of Plant Disease Management; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- De Falcis, E.; Gauchan, D.; Nankya, R.; Martinez Cotto, S.; Jarvis, D.I.; Lewis, L.; De Santis, P. Strengthening the economic sustainability of community seed banks. A sustainable approach to enhance agrobiodiversity in the production systems in low-income countries. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 803195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.; Rayamajhi, A.; Mahmud, M.S. Technological Progress Toward Peanut Disease Management: A Review. Sensors 2025, 25, 1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensaci, O.A.; Rouabah, K.; Aliat, T.; Lombarkia, N.; Plushikov, V.G.; Kucher, D.E.; Dokukin, P.A.; Temirbekova, S.K.; Rebouh, N.Y. Biological pests management for sustainable agriculture: Understanding the influence of Cladosporium-bioformulated endophytic fungi application to control Myzus persicae (Sulzer, 1776) in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.). Plants 2022, 11, 2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karthikeyan, V.; Sankaralingam, A.; Nakkeeran, S. Biological control of groundnut stem rot caused by Sclerotium rolfsii (Sacc.). Arch. Phytopathol. Plant Prot. 2006, 39, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, P.; Feng, X.; Liu, S.; Jiang, Y. Traditional uses, phytochemistry, pharmacology and toxicology of Ruta graveolens L.: A critical review and future perspectives. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2024, 6459–6485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensaci, O.A.; Aliat, T.; Berdja, R.; Popkova, A.V.; Kucher, D.E.; Gurina, R.R.; Rebouh, N.Y. The use of mycoendophyte-based bioformulations to control apple diseases: Toward an organic apple production system in the Aurès (Algeria). Plants 2022, 11, 3405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, P.G. Biological Control: Global Impacts, Challenges and Future Directions of Pest Management; Csiro Publishing: Melbourne, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, D.L.; Tillman, B.L.; Devkota, P.; Small, I.M.; Ferrell, J. Producing Peanuts Using Conservation Tillage: SSAGR185/AG187, Rev. 4/2020. EDIS 2020, 2020, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, C.E. Pathways for introgression of pest resistance into Arachis hypogaea L. Peanut Sci. 1991, 18, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burow, M.D.; Leal-Bertioli, S.C.; Simpson, C.E.; Ozias-Akins, P.; Chu, Y.; Denwar, N.N.; Chagoya, J.; Starr, J.L.; Moretzsohn, M.C.; Pandey, M.K. Marker-Assisted Selection for Biotic Stress Resistance in Peanut. Transl. Genom. Crop Breed. Biot. Stress 2013, 1, 125–150. [Google Scholar]

- Knauft, D.A.; Ozias-Akins, P. Recent methodologies for germplasm enhancement and breeding. In Advances in Peanut Science; American Peanut Research and Education Society: Alexandria, VA, USA, 1995; pp. 54–94. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, Y.; Wu, C.; Holbrook, C.; Tillman, B.; Person, G.; Ozias-Akins, P. Marker-assisted selection to pyramid nematode resistance and the high oleic trait in peanut. Plant Genome 2011, 4, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Chu, Y.; Dang, P.; Tang, Y.; Jiang, T.; Clevenger, J.P.; Ozias-Akins, P.; Holbrook, C.; Wang, M.L.; Campbell, H. Identification of QTLs for resistance to leaf spots in cultivated peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) through GWAS analysis. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2020, 133, 2051–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neelakandan, A.K.; Wright, D.A.; Traore, S.M.; Ma, X.; Subedi, B.; Veeramasu, S.; Spalding, M.H.; He, G. Application of CRISPR/Cas9 system for efficient gene editing in peanut. Plants 2022, 11, 1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishna, G.; Singh, B.K.; Kim, E.K.; Morya, V.K.; Ramteke, P.W. Progress in genetic engineering of peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.)—A review. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2015, 13, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.; Cazenave, A.-B.; Oakes, J.; McCall, D.; Thomason, W.; Abbott, L.; Balota, M. Aerial high-throughput phenotyping of peanut leaf area index and lateral growth. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 21661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farooq, M.A.; Gao, S.; Hassan, M.A.; Huang, Z.; Rasheed, A.; Hearne, S.; Prasanna, B.; Li, X.; Li, H. Artificial intelligence in plant breeding. Trends Genet. 2024, 40, 891–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hina, A.; Cao, Y.; Song, S.; Li, S.; Sharmin, R.A.; Elattar, M.A.; Bhat, J.A.; Zhao, T. High-resolution mapping in two RIL populations refines major “QTL Hotspot” regions for seed size and shape in soybean (Glycine max L.). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, M.K.; Monyo, E.; Ozias-Akins, P.; Liang, X.; Guimarães, P.; Nigam, S.N.; Upadhyaya, H.D.; Janila, P.; Zhang, X.; Guo, B. Advances in Arachis genomics for peanut improvement. Biotechnol. Adv. 2012, 30, 639–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Luo, T.; Guo, X.; Zou, X.; Zhou, D.; Afrin, S.; Li, G.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, R.; Luo, Z. PgMYB2, a MeJA-responsive transcription factor, positively regulates the dammarenediol synthase gene expression in Panax ginseng. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Feng, S.; Chen, C.; Guo, Y.; Knapp, S.; Culbreath, A.; He, G.; Wang, M.L.; Zhang, X.; Holbrook, C.C. An integrated genetic linkage map of cultivated peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) constructed from two RIL populations. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2012, 124, 653–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, M.K.; Wang, H.; Khera, P.; Vishwakarma, M.K.; Kale, S.M.; Culbreath, A.K.; Holbrook, C.C.; Wang, X.; Varshney, R.K.; Guo, B. Genetic dissection of novel QTLs for resistance to leaf spots and tomato spotted wilt virus in peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H.; Tan, X.; Hou, J.; Gong, Z.; Qin, X.; Nie, J.; Zhu, H.; Zhong, S. Separation, purification, structure characterization, and immune activity of a polysaccharide from Alocasia cucullata obtained by freeze-thaw treatment. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 282, 137232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Tseng, Y.-C.; Peng, Z.; Lopez, Y.; Chen, C.Y.; Tillman, B.L.; Dang, P.; Wang, J. Refining a major QTL controlling spotted wilt disease resistance in cultivated peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) and evaluating its contribution to the resistance variations in peanut germplasm. BMC Genet. 2018, 19, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varma, T.; Dwivedi, S.; Pande, S.; Gowda, M. SSR markers associated with resistance to rust (Puccinia arachidis Speg.) in groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.). SABRAO J. Breed. Genet. 2005, 37, 107–119. [Google Scholar]

- Mondal, S.; Badigannavar, A.; D’Souza, S. Molecular tagging of a rust resistance gene in cultivated groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.) introgressed from Arachis cardenasii. Mol. Breed. 2012, 29, 467–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Liu, N.; Huang, L.; Luo, H.; Zhou, X.; Lei, Y.; Yan, L.; Wang, X.; Chen, W.; Kang, Y. Identification and application of a candidate gene AhAftr1 for aflatoxin production resistance in peanut seed (Arachis hypogaea L.). J. Adv. Res. 2024, 62, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliana, P.; He, X.; Kabir, M.R.; Roy, K.K.; Anwar, M.B.; Marza, F.; Poland, J.; Shrestha, S.; Singh, R.P.; Singh, P.K. Genome-wide association mapping for wheat blast resistance in CIMMYT’s international screening nurseries evaluated in Bolivia and Bangladesh. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 15972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.-X.; Yu, T.-F.; Wang, C.-X.; Wei, J.-T.; Zhang, S.-X.; Liu, Y.-W.; Chen, J.; Zhou, Y.-B.; Chen, M.; Ma, Y.-Z. Heat shock protein TaHSP17. 4, a TaHOP interactor in wheat, improves plant stress tolerance. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 246, 125694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, V.; Patel, N.; Turcotte, M.; Bossé, Y.; Paré, G.; Meyre, D. Benefits and limitations of genome-wide association studies. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2019, 20, 467–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achola, E.; Wasswa, P.; Fonceka, D.; Clevenger, J.P.; Bajaj, P.; Ozias-Akins, P.; Rami, J.-F.; Deom, C.M.; Hoisington, D.A.; Edema, R. Genome-wide association studies reveal novel loci for resistance to groundnut rosette disease in the African core groundnut collection. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2023, 136, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahajan, A.; Wessel, J.; Willems, S.M.; Zhao, W.; Robertson, N.R.; Chu, A.Y.; Gan, W.; Kitajima, H.; Taliun, D.; Rayner, N.W. Refining the accuracy of validated target identification through coding variant fine-mapping in type 2 diabetes. Nat. Genet. 2018, 50, 559–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Duan, R.; Liu, J.; Qin, Y.; Wang, X. Toward multi-stage phenotyping of soybean with multimodal UAV sensor data: A comparison of machine learning approaches for leaf area index estimation. Remote Sens. 2022, 15, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, A.S.; Wu, Y.; Chen, F.; Zhu, A.; Chen, P.; Chen, K.; Qiu, X.; Huang, X.; Zhao, H.; Chen, J. Comprehensive analysis of WUSCEL-related homeobox gene family in Ramie (Boehmeria nivea) indicates its potential role in adventitious root development. Biology 2023, 12, 1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thulasinathan, T.; Ayyenar, B.; Kambale, R.; Manickam, S.; Chellappan, G.; Shanmugavel, P.; Narayanan, M.B.; Swaminathan, M.; Muthurajan, R. Marker assisted introgression of resistance genes and phenotypic evaluation enabled identification of durable and broad-spectrum blast resistance in elite rice cultivar, CO 51. Genes 2023, 14, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyes, V.P.; Angeles-Shim, R.B.; Mendioro, M.S.; Manuel, M.C.C.; Lapis, R.S.; Shim, J.; Sunohara, H.; Nishiuchi, S.; Kikuta, M.; Makihara, D. Marker-assisted introgression and stacking of major QTLs controlling grain number (Gn1a) and number of primary branching (WFP) to NERICA cultivars. Plants 2021, 10, 844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmonds, J.; Scott, P.; Brinton, J.; Mestre, T.C.; Bush, M.; Del Blanco, A.; Dubcovsky, J.; Uauy, C. A splice acceptor site mutation in TaGW2-A1 increases thousand grain weight in tetraploid and hexaploid wheat through wider and longer grains. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2016, 129, 1099–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, M.; Afzal, F.; Gul, A.; Amir, R.; Subhani, A.; Ahmed, Z.; Mahmood, Z.; Xia, X.; Rasheed, A.; He, Z. Molecular characterization of 87 functional genes in wheat diversity panel and their association with phenotypes under well-watered and water-limited conditions. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, J.; Gao, H.; Wang, H.; Lafitte, H.R.; Archibald, R.L.; Yang, M.; Hakimi, S.M.; Mo, H.; Habben, J.E. ARGOS 8 variants generated by CRISPR-Cas9 improve maize grain yield under field drought stress conditions. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2017, 15, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Wang, C.; Liu, P.; Lei, C.; Hao, W.; Gao, Y.; Liu, Y.-G.; Zhao, K. Enhanced rice blast resistance by CRISPR/Cas9-targeted mutagenesis of the ERF transcription factor gene OsERF922. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0154027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, B.; Lucas, S.J.; Budak, H. CRISPR/Cas9 in plants: At play in the genome and at work for crop improvement. Brief. Funct. Genom. 2018, 17, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Kim, S.-T.; Ryu, J.; Kang, B.-C.; Kim, J.-S.; Kim, S.-G. CRISPR/Cpf1-mediated DNA-free plant genome editing. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueta, R.; Abe, C.; Watanabe, T.; Sugano, S.S.; Ishihara, R.; Ezura, H.; Osakabe, Y.; Osakabe, K. Rapid breeding of parthenocarpic tomato plants using CRISPR/Cas9. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekaran, J.; Brumin, M.; Wolf, D.; Leibman, D.; Klap, C.; Pearlsman, M.; Sherman, A.; Arazi, T.; Gal-On, A. Development of broad virus resistance in non-transgenic cucumber using CRISPR/Cas9 technology. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2016, 17, 1140–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Zhou, R.; Liu, P.; Yang, M.; Xin, D.; Liu, C.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, X.; Chen, Q.; Zhao, Y. Design of high-monounsaturated fatty acid soybean seed oil using GmPDCTs knockout via a CRISPR-Cas9 system. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2023, 21, 1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.; Ji, J.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Z.; Duan, K.; Wang, Y. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated editing of GmTAP1 confers enhanced resistance to Phytophthora sojae in soybean. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2023, 65, 1609–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nekrasov, V.; Wang, C.; Win, J.; Lanz, C.; Weigel, D.; Kamoun, S. Rapid generation of a transgene-free powdery mildew resistant tomato by genome deletion. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrelli, V.M.; Brambilla, V.; Rogowsky, P.; Marocco, A.; Lanubile, A. The enhancement of plant disease resistance using CRISPR/Cas9 technology. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santillán Martínez, M.I.; Bracuto, V.; Koseoglou, E.; Appiano, M.; Jacobsen, E.; Visser, R.G.; Wolters, A.-M.A.; Bai, Y. CRISPR/Cas9-targeted mutagenesis of the tomato susceptibility gene PMR4 for resistance against powdery mildew. BMC Plant Biol. 2020, 20, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Zhang, Y.; Orbović, V.; Xu, J.; White, F.F.; Jones, J.B.; Wang, N. Genome editing of the disease susceptibility gene Cs LOB 1 in citrus confers resistance to citrus canker. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2017, 15, 817–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, A.; Chen, S.; Lei, T.; Xu, L.; He, Y.; Wu, L.; Yao, L.; Zou, X. Engineering canker-resistant plants through CRISPR/Cas9-targeted editing of the susceptibility gene Cs LOB 1 promoter in citrus. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2017, 15, 1509–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, J.; James, A.; Paul, J.-Y.; Khanna, H.; Smith, M.; Peraza-Echeverria, S.; Garcia-Bastidas, F.; Kema, G.; Waterhouse, P.; Mengersen, K. Transgenic Cavendish bananas with resistance to Fusarium wilt tropical race 4. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Tu, M.; Wang, D.; Liu, J.; Li, Y.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated efficient targeted mutagenesis in grape in the first generation. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2018, 16, 844–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, K.-B.; Park, S.-J.; Park, J.-S.; Lee, H.-J.; Shin, S.Y.; Lee, S.M.; Choi, G.J.; Kim, S.-G.; Cho, H.S.; Jeon, J.-H. Editing of StSR4 by Cas9-RNPs confers resistance to Phytophthora infestans in potato. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 997888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, R.; Mohanty, J.N.; Mahanty, B.; Joshi, R.K. A single transcript CRISPR/Cas9 mediated mutagenesis of CaERF28 confers anthracnose resistance in chilli pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). Planta 2021, 254, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, X.; Zhang, F.; Zhong, Z.; Chen, R.; Wang, Y.; Chang, L.; Bock, R.; Nie, B.; Zhang, J. Generation of virus-resistant potato plants by RNA genome targeting. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2019, 17, 1814–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pröbsting, M.; Schenke, D.; Hossain, R.; Häder, C.; Thurau, T.; Wighardt, L.; Schuster, A.; Zhou, Z.; Ye, W.; Rietz, S. Loss of function of CRT1a (calreticulin) reduces plant susceptibility to Verticillium longisporum in both Arabidopsis thaliana and oilseed rape (Brassica napus). Plant Biotechnol. J. 2020, 18, 2328–2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshavareddy, G.; Rohini, S.; Ramu, S.; Sundaresha, S.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, P.A.; Udayakumar, M. Transgenics in groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.) expressing cry1AcF gene for resistance to Spodoptera litura (F.). Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2013, 19, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, L.; Chi, J.; Shu, C.; Gresshoff, P.M.; Song, F.; Huang, D.; Zhang, J. A chimeric cry8Ea1 gene flanked by MARs efficiently controls Holotrichia parallela. Plant Cell Rep. 2013, 32, 1211–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, L.; Ding, X.; Wang, H.; Sui, J.; Wang, J. Characterization of the β-1, 3-glucanase gene in peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) by cloning and genetic transformation. Genet. Mol. Res. 2014, 13, 1893–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partridge-Telenko, D.; Hu, J.; Livingstone, D.; Shew, B.; Phipps, P.; Grabau, E. Sclerotinia blight resistance in Virginia-type peanut transformed with a barley oxalate oxidase gene. Phytopathology 2011, 101, 786–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjanappa, R.B.; Gruissem, W. Current progress and challenges in crop genetic transformation. J. Plant Physiol. 2021, 261, 153411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halder, M.; Jha, S. Enhanced trans-resveratrol production in genetically transformed root cultures of Peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.). Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. (PCTOC) 2016, 124, 555–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.Y.; Wei, Z.M.; An, H.L. Transgenic peanut plants obtained by particle bombardment via somatic embryogenesis regeneration system. Cell Res. 2001, 11, 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodo, H.W.; Konan, K.N.; Chen, F.C.; Egnin, M.; Viquez, O.M. Alleviating peanut allergy using genetic engineering: The silencing of the immunodominant allergen Ara h 2 leads to its significant reduction and a decrease in peanut allergenicity. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2008, 6, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, M.; Ramu, S.; Jathish, P.; Sreevathsa, R.; Reddy, P.C.; Prasad, T.; Udayakumar, M. Overexpression of AtNAC2 (ANAC092) in groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.) improves abiotic stress tolerance. Plant Biotechnol. Rep. 2014, 8, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthik, S.; Pavan, G.; Sathish, S.; Siva, R.; Kumar, P.S.; Manickavasagam, M. Genotype-independent and enhanced in planta Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated genetic transformation of peanut [Arachis hypogaea (L.)]. 3 Biotech 2018, 8, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkatesh, B.; Vennapusa, A.R.; Kumar, N.J.; Jayamma, N.; Reddy, B.M.; Johnson, A.; Madhusudan, K.; Pandurangaiah, M.; Kiranmai, K.; Sudhakar, C. Co-expression of stress-responsive regulatory genes, MuNAC4, MuWRKY3 and MuMYB96 associated with resistant-traits improves drought adaptation in transgenic groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.) plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1055851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huai, D.; Wu, J.; Xue, X.; Hu, M.; Zhi, C.; Pandey, M.K.; Liu, N.; Huang, L.; Bai, D.; Yan, L. Red fluorescence protein (DsRed2) promotes the screening efficiency in peanut genetic transformation. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1123644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatachalam, P.; Geetha, N.; Jayabalan, N.; Saravanababu; Sita, L. Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation of groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.): An assessment of factors affecting regeneration of transgenic plants. J. Plant Res. 1998, 111, 565–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, S.; Tuli, R. Optimization of factors for efficient recovery of transgenic peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.). Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. (PCTOC) 2012, 109, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, M.; Kumar Trivedi, P.; Pandey, A. Emerging tools and paradigm shift of gene editing in cereals, fruits, and horticultural crops for enhancing nutritional value and food security. Food Energy Secur. 2021, 10, e258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keerthana, D.; Reddy, J. A Novel Genetic Approach in Management of Insect Pests. 2023, Volume 1, pp. 1–16. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/370497841_Chapter_-1_A_Novel_Genetic_Approach_in_Management_of_Insect_Pests_Chapter_-1_A_Novel_Genetic_Approach_in_Management_of_Insect_Pests (accessed on 18 November 2023).

- Van Eck, J. Applying gene editing to tailor precise genetic modifications in plants. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 13267–13276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, H. CRISPR technology is revolutionizing the improvement of tomato and other fruit crops. Hortic. Res. 2019, 6, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuster, M.; Kahmann, R. CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing approaches in filamentous fungi and oomycetes. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2019, 130, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, H.; Gao, C. CRISPR/Cas genome editing and precision plant breeding in agriculture. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2019, 70, 667–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez, M.A.; Lin, Z.D.; Moll, T.; Chauhan, R.D.; Hayden, L.; Renninger, K.; Beyene, G.; Taylor, N.J.; Carrington, J.C.; Staskawicz, B.J. Simultaneous CRISPR/Cas9-mediated editing of cassava eIF 4E isoforms nCBP-1 and nCBP-2 reduces cassava brown streak disease symptom severity and incidence. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2019, 17, 421–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohail, H.; Noor, I.; Hussain, H.; Zhang, L.; Xu, X.; Chen, X.; Yang, X. Genome editing in horticultural crops: Augmenting trait development and stress resilience. Hortic. Plant J. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauer, E.K.; Balcerzak, M.; Rocheleau, H.; Leung, W.; Schernthaner, J.; Subramaniam, R.; Ouellet, T. Genome editing of a deoxynivalenol-induced transcription factor confers resistance to Fusarium graminearum in wheat. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2020, 33, 553–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.S.; Ma, E.; Harrington, L.B.; Da Costa, M.; Tian, X.; Palefsky, J.M.; Doudna, J.A. CRISPR-Cas12a target binding unleashes indiscriminate single-stranded DNase activity. Science 2018, 360, 436–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Peng, Y.; Hua, K.; Deng, Y.; Bellizzi, M.; Gupta, D.R.; Mahmud, N.U.; Urashima, A.S.; Paul, S.K.; Peterson, G. Rapid detection of wheat blast pathogen Magnaporthe oryzae Triticum pathotype using genome-specific primers and Cas12a-mediated technology. Engineering 2021, 7, 1326–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota, A.P.Z.; Vidigal, B.; Danchin, E.G.; Togawa, R.C.; Leal-Bertioli, S.C.; Bertioli, D.J.; Araujo, A.C.G.; Brasileiro, A.C.M.; Guimaraes, P.M. Comparative root transcriptome of wild Arachis reveals NBS-LRR genes related to nematode resistance. BMC Plant Biol. 2018, 18, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wu, J. The essential role of jasmonic acid in plant–herbivore interactions–using the wild tobacco Nicotiana attenuata as a model. J. Genet. Genom. 2013, 40, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Osbourn, A.; Ma, P. MYB transcription factors as regulators of phenylpropanoid metabolism in plants. Mol. Plant 2015, 8, 689–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Andrade Luz, G.; da Costa Gomes, M.F.; Ferreira-Neto, J.R.C.; Da Costa, A.F.; Sperandio, M.V.L.; Benko-Iseppon, A.M.; Kido, E.A. Unveiling Dynamic Defense Pathways: Transcriptome Analysis of Phenylpropanoids and (Iso) flavonoids in Cowpea Leaves Post-CABMV Inoculation. Biochem. Genet. 2025; online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gantz, V.M.; Akbari, O.S. Gene editing technologies and applications for insects. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2018, 28, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullah, F.; Gul, H.; Abbas, A.; Hafeez, M.; Desneux, N.; Li, Z. Genome editing in crops to control insect pests. In Sustainable Agriculture in the Era of the OMICs Revolution; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 297–313. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Wang, G.; Zhu, Y.; Xiang, H.; Wang, W. Advances and perspectives in the application of CRISPR/Cas9 in insects. Dongwuxue Yanjiu 2016, 37, 136–143. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, H.; Zhao, S.; Zuo, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wu, Y. Functional validation of cadherin as a receptor of Bt toxin Cry1Ac in Helicoverpa armigera utilizing the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2016, 76, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlopoulos, A.; Berghammer, A.J.; Averof, M.; Klingler, M. Efficient transformation of the beetle Tribolium castaneum using the Minos transposable element: Quantitative and qualitative analysis of genomic integration events. Genetics 2004, 167, 737–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beale, M.H.; Birkett, M.A.; Bruce, T.J.; Chamberlain, K.; Field, L.M.; Huttly, A.K.; Martin, J.L.; Parker, R.; Phillips, A.L.; Pickett, J.A. Aphid alarm pheromone produced by transgenic plants affects aphid and parasitoid behavior. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 10509–10513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, D.; Liu, T.; Li, C.; Jiao, B.; Li, S.; Hou, Y.; Luo, K. Efficient CRISPR/Cas9-mediated targeted mutagenesis in Populus in the first generation. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 12217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conner, J.A.; Guimaraes, L.A.; Zhang, Z.; Marasigan, K.; Chu, Y.; Korani, W.; Ozias-Akins, P. Multiplexed silencing of 2S albumin genes in peanut. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2024, 22, 2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, E.E.; Nagalakshmi, U.; Gamo, M.E.; Huang, P.-j.; Dinesh-Kumar, S.; Voytas, D.F. Multiplexed heritable gene editing using RNA viruses and mobile single guide RNAs. Nat. Plants 2020, 6, 620–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, Y.; Kim, H.; Kim, S.-G. Virus-induced plant genome editing. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2021, 60, 101992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, E.E.; Chamness, J.C.; Voytas, D.F. Viruses as Vectors for the Delivery of Gene-Editing Reagents; Burleigh Dodds Science Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Honig, A.; Marton, I.; Rosenthal, M.; Smith, J.J.; Nicholson, M.G.; Jantz, D.; Zuker, A.; Vainstein, A. Transient expression of virally delivered meganuclease in planta generates inherited genomic deletions. Mol. Plant 2015, 8, 1292–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, H.; Ishibashi, K.; Toki, S. A split Staphylococcus aureus Cas9 as a compact genome-editing tool in plants. Plant Cell Physiol. 2017, 58, 643–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uranga, M.; Vazquez-Vilar, M.; Orzáez, D.; Daròs, J.-A. CRISPR-Cas12a genome editing at the whole-plant level using two compatible RNA virus vectors. Cris. J. 2021, 4, 761–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Z.; Abul-Faraj, A.; Li, L.; Ghosh, N.; Piatek, M.; Mahjoub, A.; Aouida, M.; Piatek, A.; Baltes, N.J.; Voytas, D.F. Efficient virus-mediated genome editing in plants using the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Mol. Plant 2015, 8, 1288–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Hu, J.; Sun, Y.; Li, B.; Zhang, D.; Li, W.; Liu, J.; Li, D.; Gao, C.; Zhang, Y. Highly efficient heritable genome editing in wheat using an RNA virus and bypassing tissue culture. Mol. Plant 2021, 14, 1787–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Su, Z.; Tian, B.; Liu, Y.; Pang, Y.; Kavetskyi, V.; Trick, H.N.; Bai, G. Development and optimization of a Barley stripe mosaic virus-mediated gene editing system to improve Fusarium head blight resistance in wheat. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2022, 20, 1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iksat, N.; Masalimov, Z.; Omarov, R. Plant virus resistance biotechnological approaches: From genes to the CRISPR/Cas gene editing system. J. Water Land Dev. 2023, 57, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, M.A.; Naqvi, R.Z.; Rahman, S.U.; Amin, I.; Mansoor, S. Plant virus-derived vectors for plant genome engineering. Viruses 2023, 15, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayda, S.; Adeel, M.; Tuccinardi, T.; Cordani, M.; Rizzolio, F. The history of nanoscience and nanotechnology: From chemical–physical applications to nanomedicine. Molecules 2019, 25, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Wakeil, N.; Alkahtani, S.; Gaafar, N. Is nanotechnology a promising field for insect pest control in IPM programs? In New Pesticides and Soil Sensors; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 273–309. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Y.; Zhu, X.; Yu, Y.; Li, C.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, F. Nanotechnology strategies for plant genetic engineering. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, 2106945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naik, B.J.; Shimoga, G.; Kim, S.-C.; Manjulatha, M.; Subramanyam Reddy, C.; Palem, R.R.; Kumar, M.; Kim, S.-Y.; Lee, S.-H. CRISPR/Cas9 and nanotechnology pertinence in agricultural crop refinement. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 843575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirer, G.S.; Silva, T.N.; Jackson, C.T.; Thomas, J.B.; Ehrhardt, D.W.; Rhee, S.Y.; Mortimer, J.C.; Landry, M.P. Nanotechnology to advance CRISPR–Cas genetic engineering of plants. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2021, 16, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Zhao, F.-J.; Kopittke, P.M. Engineering crops without genome integration using nanotechnology. Trends Plant Sci. 2019, 24, 574–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z.; Jiang, R.; Chen, J.; Chen, W. Nanoparticle-mediated gene transformation strategies for plant genetic engineering. Plant J. 2020, 104, 880–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmar, S.; Mahmood, T.; Fiaz, S.; Mora-Poblete, F.; Shafique, M.S.; Chattha, M.S.; Jung, K.-H. Advantage of nanotechnology-based genome editing system and its application in crop improvement. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 663849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Babili, S.; Bouwmeester, H.J. Strigolactones, a novel carotenoid-derived plant hormone. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2015, 66, 161–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, H.; Demirer, G.S.; González-Grandío, E.; Fan, C.; Landry, M.P. Engineering DNA nanostructures for siRNA delivery in plants. Nat. Protoc. 2020, 15, 3064–3087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, R.; Ming, Z.; Yan, L.; Li, S.; Wang, F.; Ma, S.; Yu, C.; Yang, M.; Chen, L.; Chen, L. DWARF14 is a non-canonical hormone receptor for strigolactone. Nature 2016, 536, 469–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsanova, T.; Stefanova, L.; Topalova, L.; Atanasov, A.; Pantchev, I. DNA-free gene editing in plants: A brief overview. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2021, 35, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, L.; Ouyang, K.; Xu, X.; Xu, L.; Wen, C.; Zhou, X.; Qin, Z.; Xu, Z.; Sun, W.; Liang, Y. Nanoparticle delivery of CRISPR/Cas9 for genome editing. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 673286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, S.H.; Hendrix, B.; Hoffer, P.; Sanders, R.A.; Zheng, W. Carbon dots for efficient small interfering RNA delivery and gene silencing in plants. Plant Physiol. 2020, 184, 647–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathiya, S.; Antony, C.; Ghodke, P.K. Plant disease identification using IoT and deep learning algorithms. In Artificial Intelligence for Signal Processing and Wireless Communication; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2022; pp. 11–46. [Google Scholar]

- Kassim, Y.B.; Oteng-Frimpong, R.; Puozaa, D.K.; Sie, E.K.; Abdul Rasheed, M.; Abdul Rashid, I.; Danquah, A.; Akogo, D.A.; Rhoads, J.; Hoisington, D. High-throughput plant phenotyping (HTPP) in resource-constrained research programs: A working example in Ghana. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, R.R.; Reynolds, M.; Pinto, F.; Khan, M.A.; Bhat, M.A. High-throughput phenotyping for crop improvement in the genomics era. Plant Sci. 2019, 282, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakoor, N.; Lee, S.; Mockler, T.C. High throughput phenotyping to accelerate crop breeding and monitoring of diseases in the field. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2017, 38, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorani, F.; Schurr, U. Future scenarios for plant phenotyping. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2013, 64, 267–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fahlgren, N.; Gehan, M.A.; Baxter, I. Lights, camera, action: High-throughput plant phenotyping is ready for a close-up. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2015, 24, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J.W.; Andrade-Sanchez, P.; Gore, M.A.; Bronson, K.F.; Coffelt, T.A.; Conley, M.M.; Feldmann, K.A.; French, A.N.; Heun, J.T.; Hunsaker, D.J. Field-based phenomics for plant genetics research. Field Crops Res. 2012, 133, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, G.; Ge, Y.; Hussain, W.; Baenziger, P.S.; Graef, G. A multi-sensor system for high throughput field phenotyping in soybean and wheat breeding. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2016, 128, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaerle, L.; Van Der Straeten, D. Imaging techniques and the early detection of plant stress. Trends Plant Sci. 2000, 5, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.D.; Ibaraki, Y.; Trivedi, P. Applications of RGB Color Imaging in Plants; Dutta Gupta, S., Ibaraki, Y., Eds.; Taylor & Francis eBooks: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014; pp. 41–62. [Google Scholar]

- Montes, J.M.; Melchinger, A.E.; Reif, J.C. Novel throughput phenotyping platforms in plant genetic studies. Trends Plant Sci. 2007, 12, 433–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montesinos-López, O.A.; Herr, A.W.; Crossa, J.; Carter, A.H. Genomics combined with UAS data enhances prediction of grain yield in winter wheat. Front. Genet. 2023, 14, 1124218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Pradhan, S.; Shahi, D.; Khan, J.; Mcbreen, J.; Bai, G.; Murphy, J.P.; Babar, M.A. Increased prediction accuracy using combined genomic information and physiological traits in a soft wheat panel evaluated in multi-environments. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 7023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Barrios, G.; Robles-Zazueta, C.A.; Montesinos-López, A.; Montesinos-López, O.A.; Reynolds, M.P.; Dreisigacker, S.; Carrillo-Salazar, J.A.; Acevedo-Siaca, L.G.; Guerra-Lugo, M.; Thompson, G. Integration of physiological and remote sensing traits for improved genomic prediction of wheat yield. Plant Genome 2025, 18, e70110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maggiorelli, A.; Baig, N.; Prigge, V.; Bruckmüller, J.; Stich, B. Using drone-retrieved multispectral data for phenomic selection in potato breeding. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2024, 137, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Y.; Wan, S.; Zhang, L. Detection of peanut leaf spots disease using canopy hyperspectral reflectance. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2019, 156, 677–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radoglou-Grammatikis, P.; Sarigiannidis, P.; Lagkas, T.; Moscholios, I. A compilation of UAV applications for precision agriculture. Comput. Netw. 2020, 172, 107148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, M.D.; Holzinger, E.R.; Li, R.; Pendergrass, S.A.; Kim, D. Methods of integrating data to uncover genotype–phenotype interactions. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2015, 16, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Saand, M.A.; Huang, L.; Abdelaal, W.B.; Zhang, J.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Sirohi, M.H.; Wang, F. Applications of multi-omics technologies for crop improvement. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 563953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, A.; Mir, Z.A.; Almalki, M.A.; Deshmukh, R.; Ali, S. Genomics-assisted breeding: A powerful breeding approach for improving plant growth and stress resilience. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosamia, T.C.; Dodia, S.M.; Mishra, G.P.; Ahmad, S.; Joshi, B.; Thirumalaisamy, P.P.; Kumar, N.; Rathnakumar, A.L.; Sangh, C.; Kumar, A. Unraveling the mechanisms of resistance to Sclerotium rolfsii in peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) using comparative RNA-Seq analysis of resistant and susceptible genotypes. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0236823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, L.; Han, S.; Yuan, M.; Ma, X.; Hagan, A.; He, G. Transcriptomic analyses reveal the expression and regulation of genes associated with resistance to early leaf spot in peanut. BMC Res. Notes 2020, 13, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Ren, X.; Zhou, X.; Huang, L.; Yan, L.; Lei, Y.; Liao, B.; Huang, J.; Huang, S.; Wei, W. Dynamics in the resistant and susceptible peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) root transcriptome on infection with the Ralstonia solanacearum. BMC Genom. 2014, 15, 1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, K.; Wang, F.; Nong, X.; McNeill, M.R.; Liu, S.; Wang, G.; Cao, G.; Zhang, Z. Response of peanut Arachis hypogaea roots to the presence of beneficial and pathogenic fungi by transcriptome analysis. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathod, V.; Hamid, R.; Tomar, R.S.; Patel, R.; Padhiyar, S.; Kheni, J.; Thirumalaisamy, P.; Munshi, N.S. Comparative RNA-Seq profiling of a resistant and susceptible peanut (Arachis hypogaea) genotypes in response to leaf rust infection caused by Puccinia arachidis. 3 Biotech 2020, 10, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangurde, S.S.; Nayak, S.N.; Joshi, P.; Purohit, S.; Sudini, H.K.; Chitikineni, A.; Hong, Y.; Guo, B.; Chen, X.; Pandey, M.K. Comparative transcriptome analysis identified candidate genes for late leaf spot resistance and cause of defoliation in groundnut. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Liu, H.; Yan, M.; Qi, F.; Wang, Y.; Sun, Z.; Huang, B.; Dong, W.; Tang, F.; Zhang, X. Differential gene expression in leaf tissues between mutant and wild-type genotypes response to late leaf spot in peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.). PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0183428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandini, D.; Mohan, J.S.S.; Singh, G. Induction of systemic acquired resistance in Arachis hypogaea L. by Sclerotium rolfsii derived elicitors. J. Phytopathol. 2010, 158, 594–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jogi, A.; Kerry, J.W.; Brenneman, T.B.; Leebens-Mack, J.H.; Gold, S.E. Identification of genes differentially expressed during early interactions between the stem rot fungus (Sclerotium rolfsii) and peanut (Arachis hypogaea) cultivars with increasing disease resistance levels. Microbiol. Res. 2016, 184, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Jin, H.; Raza, A.; Huang, Y.; Gu, D.; Zou, X. WRKY genes provide novel insights into their role against Ralstonia solanacearum infection in cultivated peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 986673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro-Moretti, F.R.; Gentzel, I.N.; Mackey, D.; Alonso, A.P. Metabolomics as an emerging tool for the study of plant–pathogen interactions. Metabolites 2020, 10, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, X.; Wang, L.; Guo, Y.; ul Arifeen, M.Z.; Cai, X.; Xue, Y.; Bu, Y.; Wang, G.; Liu, C. A comparative transcriptomic and proteomic analysis of hexaploid wheat’s responses to colonization by Bacillus velezensis and Gaeumannomyces graminis, both separately and combined. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2019, 32, 1336–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, J.; Kim, K.-T.; Choi, J.; Cheong, K.; Ko, J.; Choi, G.; Lee, H.; Lee, G.-W.; Park, S.-Y.; Kim, S. Alternative splicing diversifies the transcriptome and proteome of the rice blast fungus during host infection. RNA Biol. 2022, 19, 373–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Xia, X.; Guo, M.; Zhong, L.; Zhang, X.; Duan, X.; Liu, J.; Huang, R. 2-Methoxy-1, 4-naphthoquinone regulated molecular alternation of Fusarium proliferatum revealed by high-dimensional biological data. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 15133–15144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Zhong, C.; Sun, J.; Chen, H. Revealing the different resistance mechanisms of banana ‘Guijiao 9’to Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cubense tropical race 4 using comparative proteomic analysis. J. Proteom. 2023, 283, 104937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Fokkens, L.; Rep, M. A single gene in Fusarium oxysporum limits host range. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2021, 22, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, C.; Zhou, H.; Tang, Y.; Cao, S.; Chen, J.; Zhang, J. Transcriptomic–Proteomic Analysis Revealed the Regulatory Mechanism of Peanut in Response to Fusarium oxysporum. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumera, N.; Iqbal, S.; Khan, S.; Rehman, Z.u. Fusarium oxysporum; its enhanced entomopathogenic activity with acidic silver nanoparticles against Rhipicephalus microplus ticks. Braz. J. Biol. 2023, 84, e266741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choubey, V.K.; Sakure, A.A.; Kumar, S.; Vaja, M.B.; Mistry, J.G.; Patel, D. Proteomics profiling and in silico analysis of peptides identified during Fusarium oxysporum infection in castor (Ricinus communis). Phytochemistry 2023, 213, 113776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Holbrook, C.; Lynch, R.; Guo, B. β-1, 3-Glucanase activity in peanut seed (Arachis hypogaea) is induced by inoculation with Aspergillus flavus and copurifies with a conglutin-like protein. Phytopathology 2005, 95, 506–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, V.; Amé, M.V.; Carrari, V.; Gieco, J.; Asis, R. Lipoxygenase activation in peanut seed cultivars resistant and susceptible to Aspergillus parasiticus colonization. Phytopathology 2014, 104, 1340–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Z.; Liu, C.-M. Autoxidated linolenic acid inhibits aflatoxin biosynthesis in Aspergillus flavus via oxylipin species. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2015, 81, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korani, W.; Chu, Y.; Holbrook, C.C.; Ozias-Akins, P. Insight into genes regulating postharvest aflatoxin contamination of tetraploid peanut from transcriptional profiling. Genetics 2018, 209, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, C.; Wen, S.; Liu, H.; Chen, X.; Li, H.; Hong, Y.; Liang, X. Overexpression of ARAhPR10, a member of the PR10 family, decreases levels of Aspergillus flavus infection in peanut seeds. Am. J. Plant Sci. 2013, 4, 602–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Li, C.; Yan, C.; Wang, J.; Yuan, C.; Zhang, H.; Shan, S. Transcriptome and proteome analyses of resistant preharvest peanut seed coat in response to Aspergillus flavus infection. Electron. J. Biotechnol. 2019, 39, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, D.; Yin, H.; Wang, H.; Cao, C.; Wang, J.; Zheng, J.; Liu, J. Transcriptomic and metabolomic analyses of the response of resistant peanut seeds to Aspergillus flavus infection. Toxins 2023, 15, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Yan, S.; Liu, C.; Chen, F.; Wang, T. Proteomic analysis reveals an aflatoxin-triggered immune response in cotyledons of Arachis hypogaea infected with Aspergillus flavus. J. Proteome Res. 2012, 11, 2739–2753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Lei, Y.; Wan, L.; Yan, L.; Lv, J.; Dai, X.; Ren, X.; Guo, W.; Jiang, H.; Liao, B. Comparative transcript profiling of resistant and susceptible peanut post-harvest seeds in response to aflatoxin production by Aspergillus flavus. BMC Plant Biol. 2016, 16, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaprakash, A.; Roy, A.; Thanmalagan, R.R.; Arunachalam, A.; Ptv, L. Immune response gene coexpression network analysis of Arachis hypogaea infected with Aspergillus flavus. Genomics 2021, 113, 2977–2988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, M.; Han, S.; Wang, D.; Haider, M.S.; Guo, J.; Zhao, Q.; Du, P.; Sun, Z.; Qi, F.; Zheng, Z. Gene Co-expression Network Analysis of the Comparative Transcriptome Identifies Hub Genes Associated With Resistance to Aspergillus flavus L. in Cultivated Peanut (Arachis hypogae L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 899177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Zhang, E.; Chen, X.; Li, L.; Liang, X. Identification of seed proteins associated with resistance to pre-harvested aflatoxin contamination in peanut (Arachis hypogaea L). BMC Plant Biol. 2010, 10, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Xing, M.; Zhang, L.; Han, S.; Zhang, X.; Huang, J. Integrated metabolomic and transcriptomic analysis highlight the flavonoid response to antioxidant activity and Aspergillus flavus resistance in peanut seed coats. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pei, X.; Xie, J.; Liang, C.; Utkina, A.O. Next-Generation Precision Breeding in Peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) for Disease and Pest Resistance: From Multi-Omics to AI-Driven Innovations. Insects 2026, 17, 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010063

Pei X, Xie J, Liang C, Utkina AO. Next-Generation Precision Breeding in Peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) for Disease and Pest Resistance: From Multi-Omics to AI-Driven Innovations. Insects. 2026; 17(1):63. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010063

Chicago/Turabian StylePei, Xue, Jinhui Xie, Chunhao Liang, and Aleksandra O. Utkina. 2026. "Next-Generation Precision Breeding in Peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) for Disease and Pest Resistance: From Multi-Omics to AI-Driven Innovations" Insects 17, no. 1: 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010063