Effects of Corcyra cephalonica Egg Consumption on Population Fitness and Reproduction of the Whitefly Predator Serangium japonicum (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae)

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Insect Rearing

2.2. Assessment of the Effects of Different Diets on the Population Fitness of S. japonicum

2.3. Female Ovary Dissection and Body Weight Measurement

2.4. Measurement of Female Reproduction-Related Gene Expression

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

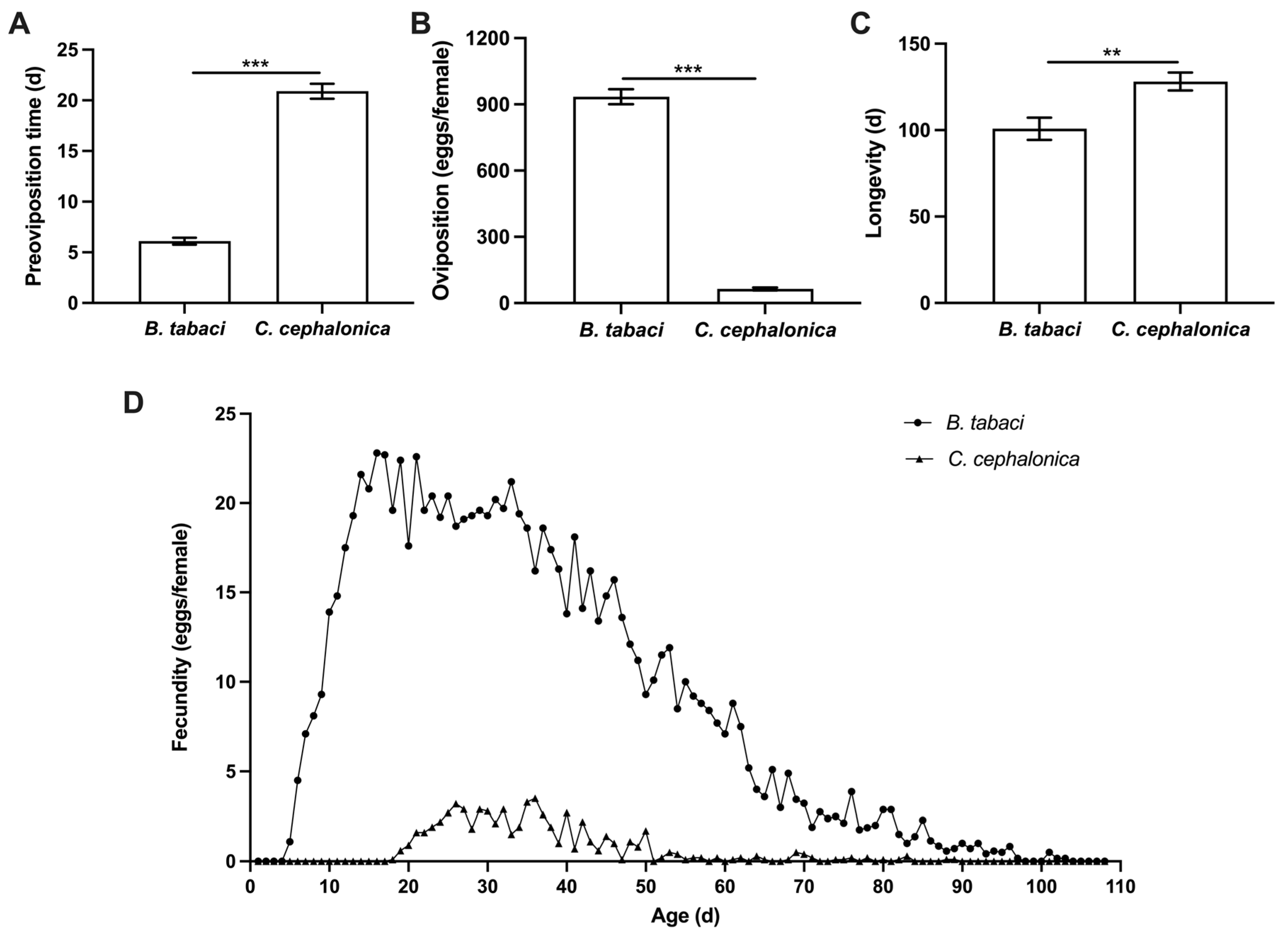

3.1. Effects of Feeding on C. cephalonica Eggs on the Population Fitness of S. japonicum

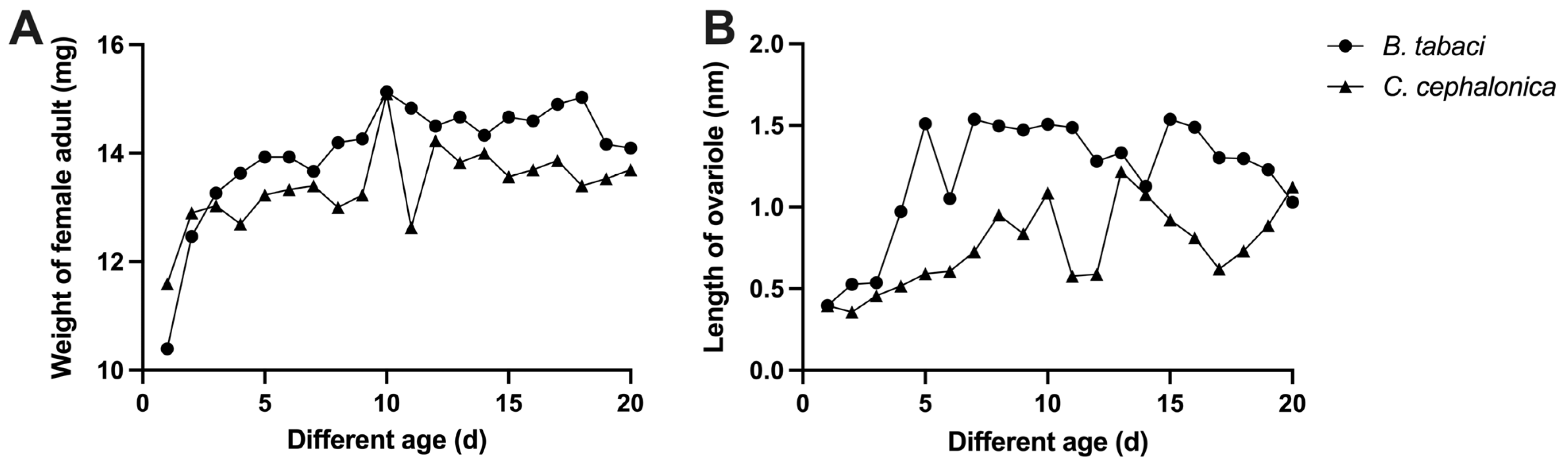

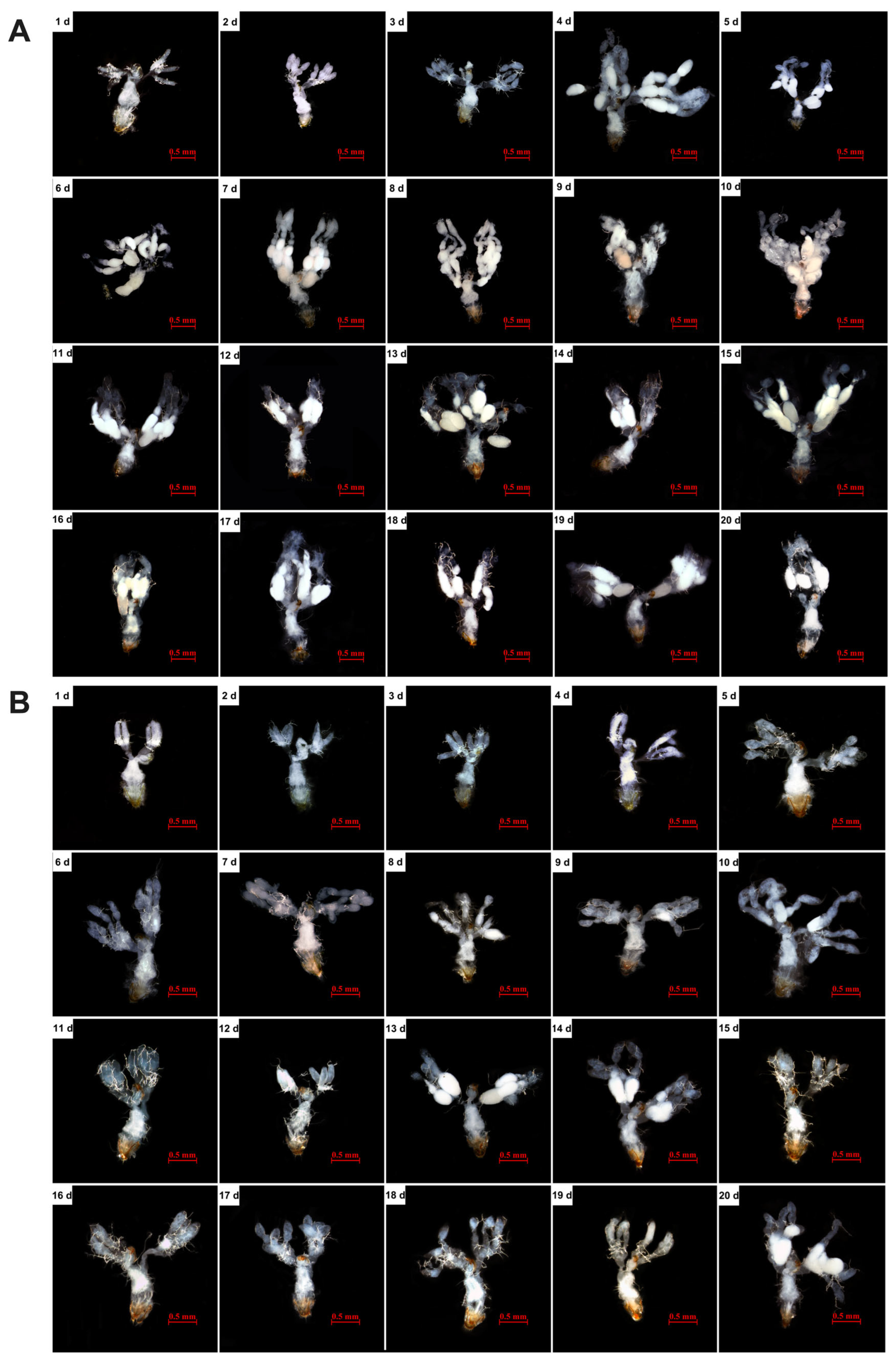

3.2. Effects of Feeding on C. cephalonica Eggs on Female Ovary Development and Body Weight of S. japonicum

3.3. Effects of Feeding on C. cephalonica Eggs on the Expression of Reproduction-Related Genes in Female S. japonicum

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| JH | Juvenile hormone |

| Met | methoprene-tolerant |

| JHAMT | Juvenile hormone acid O-methyltransferase |

| JHE | Juvenile hormone esterase |

| Vg | Vitellogenin |

| VgR | Vitellogenin receptor |

| Cu/Zn-SOD | Copper/zinc superoxide dismutase |

References

- Pathrose, B.; Chellappan, M.; Ranjith, M.T. Mass production of Insect predators. In Commercial Insects; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023; pp. 270–299. [Google Scholar]

- Lü, X.; Han, S.C.; Li, L.Y.; Grenier, S.; De Clercq, P. The potential of trehalose to replace insect hemolymph in artificial media for Trichogramma dendrolimi Matsumura (Hymenoptera: Trichogrammatidae). Insect Sci. 2013, 20, 629–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; Han, S.C.; De Clercq, P.; Dai, J.Q.; Li, L.Y. Orthogonal array design for optimization of an artificial medium for in vitro rearing of Trichogramma dendrolimi. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2014, 152, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesan, T.; Singh, S.P.; Jalali, S.K. Development of Cryptolaemus montrouzieri Mulsant (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae), a predator of mealybugs on freeze-dried artificial diet. J. Biol. Control 2001, 15, 139–142. [Google Scholar]

- Ain, Q.; Khan, A.; Riaz, A.; Suleman, N. Cold storage of predatory coccinellid Coccinella septempunctata L. (Coleoptera; Coccinellidae) to increase its shelf-life for biological control programmes. Sarhad J. Agric. 2024, 40, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.C.; Chen, H.R.; Wu, Y.H. Current status and future perspectives on natural enemies for pest control in Taiwan. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 2018, 28, 953–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.Y.; Luo, X.L.; Wei, X.Y.; Liang, J.F.; Xie, Y.H.; Wang, X.M. Effects of cold-storage temperature on the survival and growth and development of Serangium japanicum (Coleoptera:Coccinellidae). Acta Entomol. Sin. 2023, 66, 226–234. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.J.; Chen, J.H.; Avila, G.A.; Ali, M.Y.; Tian, X.Y.; Luo, Z.Y.; Zhang, F.; Shi, S.S.; Zhang, J.P. Performance of two egg parasitoids of brown marmorated stink bug before and after cold storage. Front. Physiol. 2023, 2, 1102216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakaki, S.; Jalali, M.A.; Kamali, H.; Nedved, O. Effect of low-temperature storage on the life history parameters and voracity of Hippodamia variegata (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae). Eur. J. Entomol. 2019, 116, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.N.; Zhou, W.; Lu, C.H.; Pan, Y.N.; Liu, L.Y.; Chen, W.L. Fitness implications of low-temperature storage for Eocanthecona furcellata (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 2024, 117, 1739–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.X.; Huang, Z.; Yao, S.L. Advances in studies on predators of Bemisia tabaci Gennadius. Nat. Enemies Insects 2004, 26, 34–42. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Y.; Zhi, J.R.; Li, F.L.; Jin, J.X.; Zhou, Y.H. An artificial diet for continuous maintenance of Coccinella septempunctata adults (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae). Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 2018, 32, 1122–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.X.; Hao, Y.N.; Liu, T.X. A β-carotene-amended artificial diet increases larval survival and be applicable in mass rearing of Harmonia axyridis. Biol. Control 2018, 123, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.Y.; Li, H.S.; Chen, P.T.; Pang, H. Alternative foods for the rearing of a ladybird: Successive generations of the Micraspis discolor fed on Ephestia kuehniella eggs and Brassica campestris pollen. J. Environ. Entomol. 2021, 43, 305–314. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, P.; Liu, J.; Chi, B.J.; Li, D.C.; Li, J.Y.; Liu, Y.J. Effect of different diets on the growth and development of Harmonia axyridis (Pallas). J. Appl. Entomol. 2020, 144, 911–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalali, M.A.; Reitz, S.; Mehrnejad, M.R.; Ranjbar, F.; Ziaaddini, M. Food utilization, development, and reproductive performance of Coccinella septempunctata (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) feeding on an aphid or psylla prey species. J. Econ. Entomol. 2019, 112, 571–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tun, K.M.; Clavijo McCormick, A.; Jones, T.; Minor, M. The potential of harlequin ladybird beetle Harmonia axyridis as a predator of the giant willow aphid Tuberolachnus salignus: Voracity, life history and prey preference. BioControl 2020, 65, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.R.; Zhang, S.F.; Zhang, Z.F.; Long, S.D. Comparative studies on mass rearing Xylocoris flavipes on different media. Chin. J. Biol. Control 1986, 2, 63–66. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J.Y.; Wan, F.H. Effect of three diets on development and fecundity of the ladybeetles Harmonia axyridis and Propylaea japonica. Chin. J. Biol. Control 2001, 17, 116–120. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, W.X.; Wang, Z.H.; Huang, J. Effect of alternative feeding with artificial diets and natural prey on oviposition of Delphastus catalinae (Horn). Chin. J. Biol. Control 2014, 30, 600–605. [Google Scholar]

- Fazal, S.; Ren, S.X. Interaction of Serangium japonicum (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae), an obligate predator of whitefly with immature stages of Eretmocerus sp. (Hymenoptera: Aphelinidae) within whitefly host (Homoptera: Aleyrodidae). Asian J. Plant Sci. 2004, 3, 243–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etman, A.A.M.; El-Sayed, F.M.A.; Eesa, N.M.; Moursy, L.E. Laboratory studies on the development, survival, mating behaviour and reproductive capacity of the rice moth, Corcyra cephalonica (Stainton) (Lep., Galleriidae). J. Appl. Entomol. 1988, 106, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Peng, J.; Liang, J.F.; Huang, C.Y.; Xie, Y.H.; Wang, X.M. Changes in life history parameters and transcriptome profile of Serangium japonicum associated with feeding on natural prey (Bemisia tabaci) and alternate host (Corcyra cephalonica eggs). BMC Genom. 2023, 24, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.C.; Chen, P.; Liu, J.; Chi, B.J.; Zhang, X.P.; Liu, Y.J. Artificial rearing of the ladybird Propylea japonica on a diet containing oriental armyworm, Mythimna separata. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2021, 169, 472–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Y.C.; Cai, X.M.; Yan, J.J. The natural enemies of aphids research on Coccinella septempunctata L. (II). Classification standard and ecological significance of ovarian development. Nat. Enemies Insects 1980, 2, 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Stebbings, H. Observations on cytoplasmic transport along ovarian nutritive tubes of polyphagous coleopterans. Cell Tissue Res. 1981, 220, 1531–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.X.; Li, Y.T.; Xu, J. Oogenesis in Coccinella septempunctata L. Acta Entomol. Sin. 1981, 24, 268–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wu, C.J.; Zhang, Q.W.; Ma, Z.; Sun, H.K.; He, Y.Z. Ovarian development and oogenesis of Harmonia axyridis Pallas. J. Plant Prot. 2015, 42, 237–243. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.W.; Zhang, C.; Qiu, B.L.; Wang, X.M. Reproductive system and oogenesis of Cryptolaemus montrouzieri Mulsant (Coccinellidae: Coleoptera). Chin. J. Appl. Entomol. 2016, 53, 381–389. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, L.; Chen, X.; Lv, J.; Huang, Z.D.; Pu, Z.X.; Liu, S.M. Artificial diets can manipulate the reproductive development status of predatory ladybird beetles and hold promise for their shelf-life management. Heliyon 2024, 10, e29836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.Y. Study on the Growth, Development and Reproductive Characteristics of Delphastus catalinae (Horn) Feeding on the Eggs of Ephestia kuehniella Zeller. Master’s thesis, Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University, Fuzhou, China, 2018; p. 31. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Wan, F.H.; Ji, J.H. On the application feasibility of pupal trichogramma from artificial eggs for mass rearing of Coccinella septempunctata Linnaeus. Acta Phytophy. Sin. 2001, 28, 139–145. [Google Scholar]

- Strilbytska, O.; Yurkevych, I.; Semaniuk, U.; Gospodaryov, D.; Simpson, S.J.; Lushchak, O. Life-history trade-offs in Drosophila: Flies select a diet to maximize reproduction at the expense of lfespan. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2024, 79, glae057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rho, M.S.; Lee, K.P. Macronutrient balance dictates lifespan and reproduction in a beetle, Tenebrio molitor. J. Exp. Biol. 2025, 228, jeb250281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasson, D.A.; Munoz, P.R.; Gezan, S.A.; Miller, C.W. Resource quality affects weapon and testis size and the ability of these traits to respond to selection in the leaf-footed cactus bug, Narnia femorata. Ecol. Evol. 2016, 6, 2098–2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.T.; Yu, Y.C.; Li, J.Y.; Zheng, L.; Chen, S.W.; Mao, J.J. Comparative transcriptome analysis of the effects of a non-insect artificial diet on the nutritional development of Harmonia axyridis. Insects 2025, 16, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, E.W. Multitrophic interactions among plants, aphids, alternate prey and shared natural enemies—A review. Eur. J. Entomol. 2008, 105, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Liu, H.L.; Wu, X.L.; Xiao, K.J.; He, H.G.; Huang, Q.; Pu, D.Q. Effects of artificial diet on the biological characteristics of the ladybeetle Coccinella septempunctata. Entomol. Res. 2023, 52, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyria, J.; Fruttero, L.L.; Paglione, P.A.; Canavoso, L.E. How Insects balance reproductive output and immune investment. Insects 2025, 16, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morimoto, J. Nutritional trade-offs in Drosophila melanogaster. Biology 2025, 14, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonte, M.; Samih, M.A.; De Clercq, P.D. Development and reproduction of Adalia bipunctata on factitious and artificial foods. BioControl 2010, 55, 485–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Ramos, J.A.; Rojas, M.G.; King, E.G. Significance of adult nutrition and oviposition experience on longevity and attainment of full fecundity of Catolaccus grandis (Hymenoptera: Pteromalidae). Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 1996, 89, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, A.B.; Leyria, J.; Orchard, I. The hormonal and neural control of egg production in the historically important model insect, Rhodnius prolixus: A review, with new insights in this post-genomic era. Gen. Comp. Endocr. 2022, 321–322, 114030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jindra, M.; Palli, S.R.; Riddiford, L.M. The juvenile hormone signaling pathway in insect development. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2013, 58, 181–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HuangFu, N.B.; Zhu, X.Z.; Chang, G.F.; Wang, L.; Li, D.Y.; Zhang, K.X.; Gao, X.K.; Ji, J.C.; Luo, J.Y.; Cui, J.J. Dynamic transcriptome analysis and Methoprene-tolerant geneknockdown reveal that juvenile hormone regulates oogenesis and vitellogenin synthesis in Propylea japonica. Genomics 2021, 113, 2877–2889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheng, Z.T.; Ma, L.; Cao, M.X.; Jiang, R.J.; Li, S. Juvenile hormone acid methyl transferase is a key regulatory enzyme for juvenile hormone synthesis in the Eri silkworm, Samia cynthica ricini. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 2008, 69, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinoda, T.; Itoyama, K. Juvenile hormone acid methyltransferase: A key regulatory enzyme for insect metamorphosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 11986–11991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez, C.V.; Maestro, J.L. Expression of juvenile hormone acid O-methyltransferase and juvenile hormone synthesis in Blattella germanica. Insect Sci. 2018, 25, 787–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sheikh, E.A.; Kamita, S.G.; Hammock, B.D. Effects of juvenile hormone (JH) analog insecticides on larval development and JH esterase activity in two spodopterans. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2016, 128, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munyiri, F.N.; Ishikawa, Y. Endocrine changes associated with metamorphosis and diapause induction in theyellow-spotted longicorn beetle, Psacothea hilaris. J. Insect Physiol. 2004, 50, 1075–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Han, S.P.; Qin, Q.J.; Chen, J.; Wang, D.; He, Y.Z. Molecular identification and functional characterization of vitellogenin receptor from Harmonia axyridis (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 2022, 115, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, D.X.; Pan, B.Q.; Lin, K.; Wang, X.Y.; Li, X.S.; Zheng, X.L. Regulation of reproduction by juvenile hormone synthase and degradation enzyme in Diaphorina citri. Pest Manag. Sci. 2026, 82, 992–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.Q.; Song, J.B.; Jiang, G.H.; Shang, Y.Z.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, J.F.; Xiao, L.; Chen, M.; Tang, D.M.; Tong, X.L.; et al. Juvenile hormone suppresses the FoxO-takeout axis to shorten longevity in male silkworm. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2023, 192, 105388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, R.; Bai, H.; Dolezal, A.G.; Amdam, G.; Tatar, M. Juvenile hormone regulation of Drosophila aging. BMC Biol. 2013, 11, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flatt, T.; Kawecki, T.J. Juvenile hormone as a regulator of the trade-off between reproduction and life span in Drosophila melanogaster. Evolution 2007, 61, 1980–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tower, J. Superoxide dismutase (SOD) genes and aging in Drosophila. In Healthy Ageing and Longevity; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 3, pp. 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodirov, S.A. Comparison of superoxide dismutase activity at the cell, organ, and whole-body levels. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2025, 83, 2713–2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasaki, E.; Kobayashi, K.; Matsuura, K.; Iuchi, Y. Long-lived termite queens exhibit high Cu/Zn-superoxide dismutase activity. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 5127251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Primer Name | Forward Primer Sequence | Reverse Primer Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| JHAMT | TTTGGATGTGGGATCAGGGG | TGGTGACACATCGACTGCAT |

| Met | TCGTACATAGGCGAGTTGGC | TCGAAGTGCGGCATGTTTTG |

| JHE | ACTGAACGCGACATCTGAGG | TGGGATCCTGTGGCGTAAAC |

| Vg | AGCCAATACCTCCGCAACAA | AGGATCACGAACAACGCAGT |

| VgR | AGTGGGCATTGCATTCCTGA | ACAAGCGCCTGATTTGCATC |

| Cu/Zn SOD | GGTGGACCAGCTGATGCTTT | CCTCTTGGAGCGCCAGATAA |

| β-actin | CGTACCACCGGTATCGTATTG | CGGAGGATAGCATGAGGTAAAG |

| Type of Prey | Length of Minimum Ovariole (mm) | Length of Maximum Ovariole (mm) | Growth Rate of Length (%) | Minimum Body Weight (mg) | Maximum Body Weight (mg) | Growth Rate of Weight (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B. tabaci | 0.40 ± 0.01 | 1.56 ± 0.03 | 293.44 ± 5.10 | 10.40 ± 0.44 | 15.77 ± 0.18 | 52.24 ± 7.10 |

| C. cephalonica | 0.36 ± 0.01 | 1.26 ± 0.02 | 253.05 ± 14.77 | 11.37 ± 0.30 | 15.73 ± 0.38 | 38.78 ± 7.04 |

| p value | 0.003 | <0.001 | 0.061 | 0.140 | 0.941 | 0.249 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liang, J.; Peng, J.; Cao, H.; Hu, Y.; Ullah, M.I.; Ali, S.; Wang, X. Effects of Corcyra cephalonica Egg Consumption on Population Fitness and Reproduction of the Whitefly Predator Serangium japonicum (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae). Insects 2026, 17, 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010062

Liang J, Peng J, Cao H, Hu Y, Ullah MI, Ali S, Wang X. Effects of Corcyra cephalonica Egg Consumption on Population Fitness and Reproduction of the Whitefly Predator Serangium japonicum (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae). Insects. 2026; 17(1):62. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010062

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiang, Jianfeng, Jing Peng, Huiyi Cao, Yuxia Hu, Muhammad Irfan Ullah, Shaukat Ali, and Xingmin Wang. 2026. "Effects of Corcyra cephalonica Egg Consumption on Population Fitness and Reproduction of the Whitefly Predator Serangium japonicum (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae)" Insects 17, no. 1: 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010062

APA StyleLiang, J., Peng, J., Cao, H., Hu, Y., Ullah, M. I., Ali, S., & Wang, X. (2026). Effects of Corcyra cephalonica Egg Consumption on Population Fitness and Reproduction of the Whitefly Predator Serangium japonicum (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae). Insects, 17(1), 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010062