The First Record of Whitefly (Hemiptera, Sternorrhyncha, Aleyrodidae) from Bitterfeld Amber

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Geological Setting

2.2. Morphology and Documentation

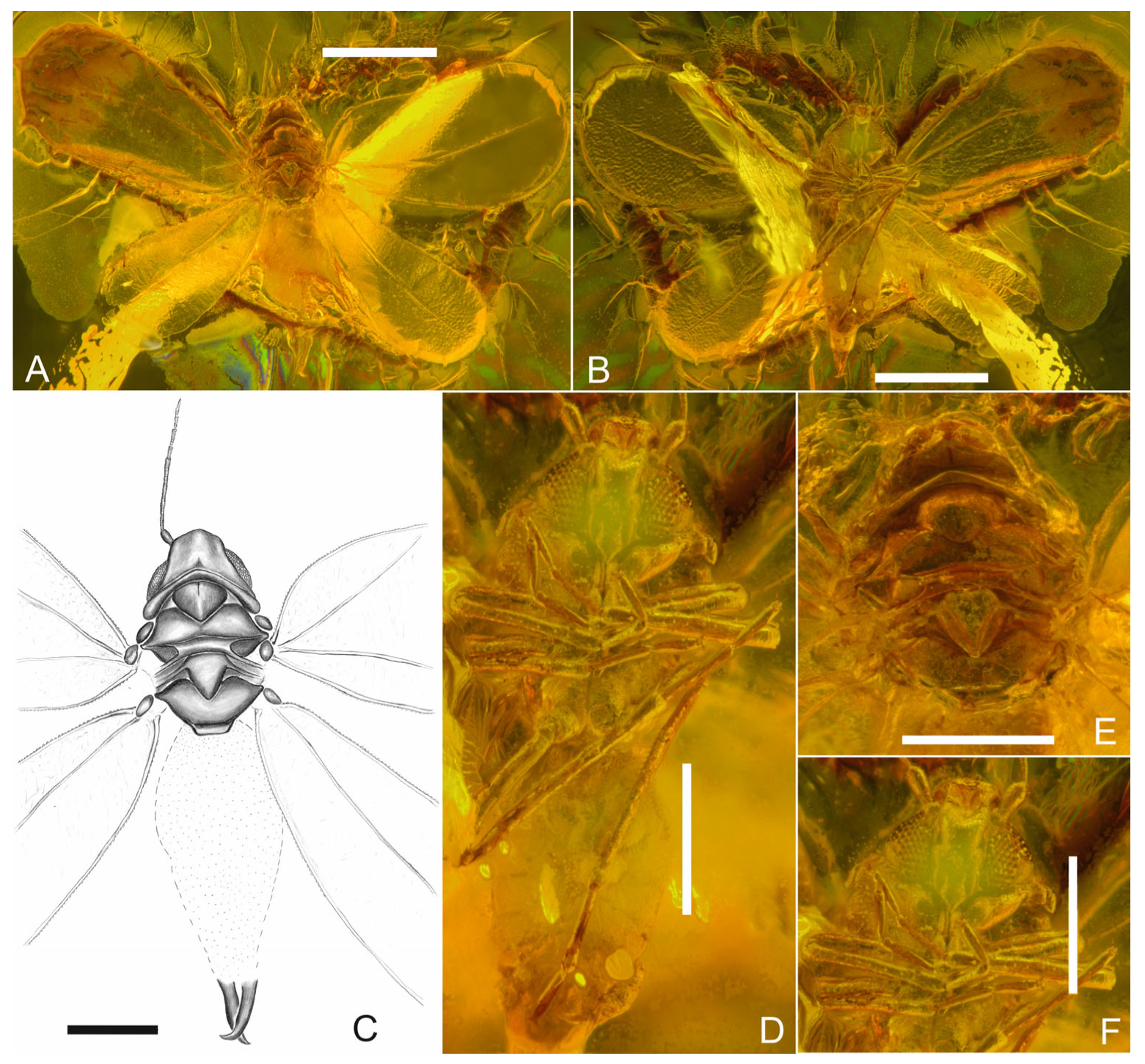

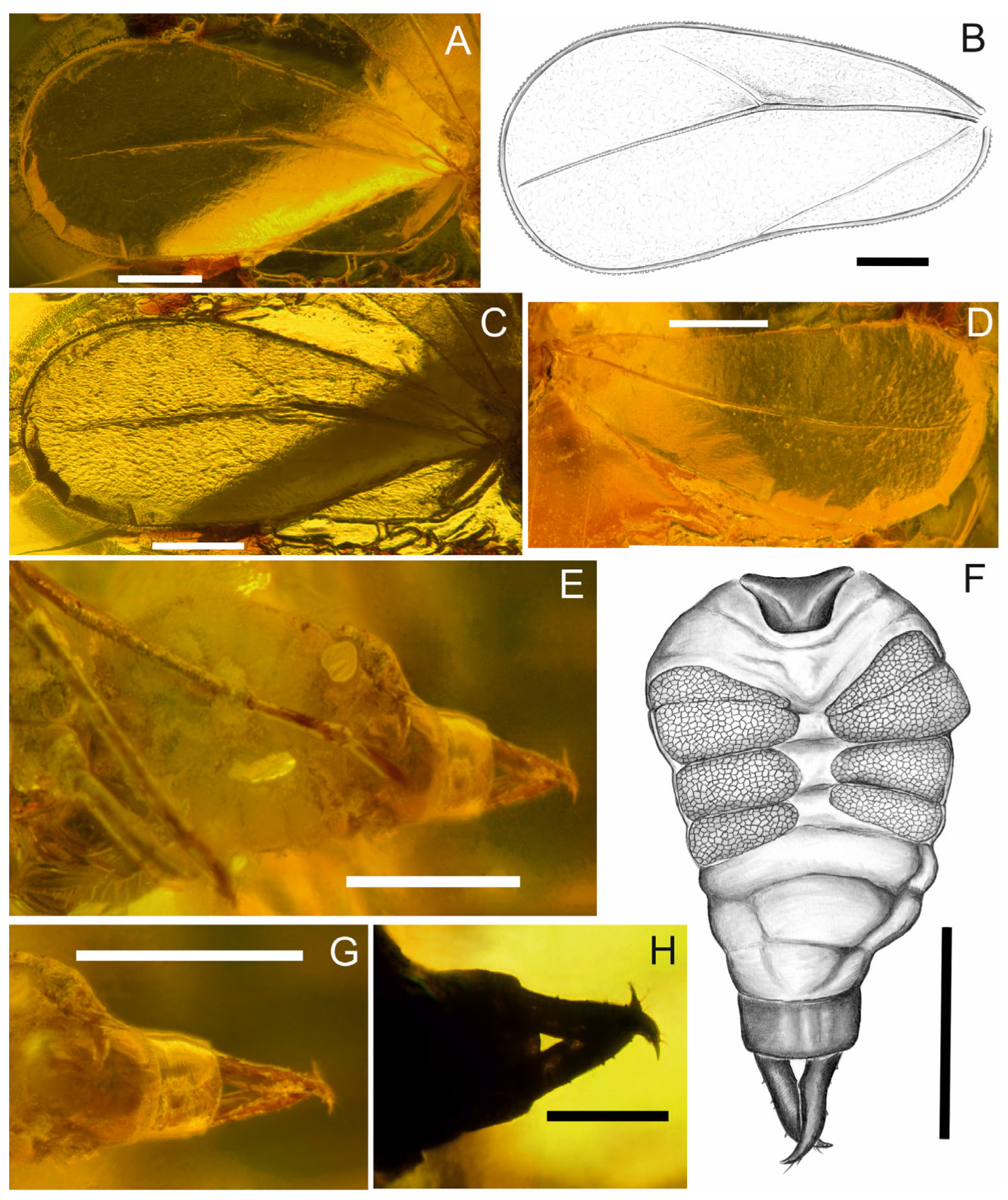

3. Results

Systematic Palaeontology

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Szwedo, J. The unity, diversity and conformity of bugs (Hemiptera) through time. Earth Environ. Sci. Trans. R. Soc. Edinb. 2018, 107, 109–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drohojowska, J.; Szwedo, J.; Żyła, D.; Huang, D.-Y.; Müller, P. Fossils reshape the Sternorrhyncha evolutionary tree (Insecta, Hemiptera). Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 11390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, N.; Wang, M.M.; Huang, W.C.; Wu, Z.Y.; Shao, R.; Yin, X.M. Phylogeny and evolution of hemipteran insects based on expanded genomic and transcriptomic data. BMC Biol. 2024, 22, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, T.J. Biodiversity of Heteroptera. In Insect Biodiversity: Science and Society, 2nd ed.; Foottit, A.G., Adler, P.H., Eds.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2017; Volume 1, pp. 279–336. [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett, C.R.; Deitz, L.L.; Dmitriev, D.A.; Sanborn, A.F.; Soulier-Perkins, A.; Wallace, M.S. The diversity of the true hoppers (Hemiptera: Auchenorrhyncha). In Insect Biodiversity: Science and Society; Foottit, A.G., Adler, P.H., Eds.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2018; pp. 501–590. [Google Scholar]

- Hardy, N.B. The biodiversity of Sternorrhyncha: Scale insects, aphids, psyllids, and whiteflies. In Insect Biodiversity: Science and Society; Foottit, A.G., Adler, P.H., Eds.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2018; pp. 591–625. [Google Scholar]

- Kieran, T.J.; Gordon, E.R.; Forthman, M.; Hoey-Chamberlain, R.; Kimball, R.T.; Faircloth, B.C.; Weirauch, C.; Glenn, T.C. Insight from an ultraconserved element bait set designed for hemipteran phylogenetics integrated with genomic resources. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2019, 130, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberemok, V.V.; Gal’chinsky, N.V.; Useinov, R.Z.; Novikov, I.A.; Puzanova, Y.V.; Filatov, R.I.; Kouakou, N.J.; Kouame, K.F.; Kra, K.D.; Laikova, K.V. Four most pathogenic superfamilies of insect pests of suborder Sternorrhyncha: Invisible superplunderers of plant vitality. Insects 2023, 14, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerling, D. Whiteflies: Their Bionomics, Pest Status and Management; Intercept Ltd.: Andover, The Netherlands, 1990; 348p. [Google Scholar]

- Grimaldi, D.; Engel, M.S. Evolution of the Insects; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005; 772p. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, G.A.; Martin, J.H.; Drohojowska, J.; Szwedo, J.; Dubey, A.K.; Dooley, J.W.; Stocks, I.C. Whiteflies of the world (Hemiptera: Sternorrhyncha, Aleyrodidae)—A catalogue of the taxonomy, distribution, hosts and natural enemies of whiteflies. Zootaxa, 2025; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Shcherbakov, D.E. The most primitive whiteflies (Hemiptera; Aleyrodidae; Bernaeinae subfam. nov.) from the Mesozoic of Asia and Burmese amber, with an overview of Burmese amber hemipterans. Bull. Br. Mus. Nat. Hist. (Geol.) 2000, 56, 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- Drohojowska, J.; Wegierek, P.; Evans, G.A.; Huang, D.Y. Are contemporary whiteflies living fossils? Morphology and systematic status of the oldest representatives of the Middle-late Jurassic Aleyrodomorpha (Sternorrhyncha, Hemiptera) from Daohugou. Palaeoentomology 2019, 2, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drohojowska, J.; Zmarzły, M.; Szwedo, J. The discovery of a fossil whitefly from Lower Lusatia (Germany) presents a challenge to current ideas about Baltic amber. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 23102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, K.B.; Winans, R.E.; Botto, R.E. The nature and fate of natural resins in the geosphere—II. Identification, classification and nomenclature of resinites. Org. Geochem. 1992, 18, 829–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matuszewska, A. Bursztyn i Inne Żywice Kopalne, Subfossylne i Współczesne; Uniwersytet Śląski. Oficyna Wydawnicza Wacław Walasek: Katowice, Poland, 2010; 234p. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Kosmowska-Ceranowicz, B. Bursztyn w Polsce i na Świecie. Amber in Poland and in the World, 2nd ed.; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego: Warsaw, Poland, 2017; 311p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, A.P.; McKellar, R.C.; Tappert, R.; Sodhi, R.N.S.; Muehlenbachs, K. Bitterfeld amber is not Baltic amber: Three geochemical tests and further constraints on the botanical affinities of succinite. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 2016, 225, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadowski, E.M.; Schmidt, A.R.; Seyfullah, L.J.; Kunzmann, L. Conifers of the “Baltic Amber Forest” and their palaeoecological significance. Stapfia 2017, 106, 1–73. [Google Scholar]

- Perkovsky, E.; Rasnitsyn, A.; Vlaskin, A.; Taraschuk, M. A comparative analysis of the Baltic and Rovno amber arthropod faunas: Representative samples. Afr. Invert. 2007, 48, 229–245. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlop, J.A.; Kotthoff, U.; Hammel, J.U.; Ahrens, J.; Harms, D. Arachnids in Bitterfeld amber: A unique fauna of fossils from the heart of Europe or simply old friends? Evol. Syst. 2018, 2, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rappsilber, I. Bitterfelder Bernstein: Geschichte, Vielfalt, Entstehung/Bitterfeld Amber: History, Diversity, Origin; Ampyx Verlag: Halle (Saale), Germany, 2022; 323p. [Google Scholar]

- Krumbiegel, G.; Kosmowska-Ceranowicz, B. Fossile Harze der Umgebung von Halle (Saale) in der Sammlung des Geiseltalmuseums der Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg. Wiss. Z. Univ. Halle 1992, 41, 5–35. [Google Scholar]

- Fuhrmann, R. Die Bitterfelder Bernsteinarten. Mauritiana 2010, 21, 13–58. [Google Scholar]

- Knuth, G.; Koch, T.; Rappsilber, I.; Volland, L. Zum Bernstein im Bitterfelder Raum-Geologie und genetische Aspekte. Hallesches Jahrb. Geowiss. 2002, 24, 35–46. [Google Scholar]

- Blumenstengel, H. Zur Palynologie und Stratigraphie der Bitterfelder Bernsteinvorkommen (Tertiär). In Bitterfelder Bernstein: Lagerstätte, Rohstoff, Folgenutzung. Programm, Vortragskurzfassungen und Exkursionsführer zum 16. Treffen des Arbeitskreises Bergbaufolgelandschaften, Bitterfeld, 4/5.07.2004; Wimmer, R., Holz, U., Rascher, J., Eds.; Exkurs.f. u. Veröfftl. GGW; Deutsche Geologische Gesellschaft—Geologische Vereinigung (DGGV): Berlin, Germany, 2004; Volume 224, pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Fuhrmann, R. Entstehung, Entdeckung und Erkundung der Bernsteinlagerstätte Bitterfeld. In Bitterfelder Bernstein: Lagerstätte, Rohstoff, Folgenutzung. Programm, Vortragskurzfassungen und Exkursionsführer zum 16. Treffen des Arbeitskreises Bergbaufolgelandschaften, Bitterfeld, 4/5.07.2004; Wimmer, R., Holz, U., Rascher, J., Eds.; Exkurs.f. u. Veröfftl. GGW; Deutsche Geologische Gesellschaft—Geologische Vereinigung (DGGV): Berlin, Germany, 2004; Volume 224, pp. 25–31. [Google Scholar]

- Rappsilber, I. Fauna und Flora des Bitterfelder Bernsteinwaldes. Eine Auflistung der bis 2014 Publizierten Organismentaxa aus dem Bitterfelder Bernstein; Ampyx-Verlag: Halle (Saale), Germany, 2016; 78p. [Google Scholar]

- Pańczak, J.; Kossakowski, P.; Zakrzewski, A. Biomarkers in fossil resins and their palaeoecological significance. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2023, 242, 104455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, S.; Otto, A.; Krumbiegel, G.; Simoneit, B.R.T. The natural product biomarkers in succinite, glessite and stantienite ambers from Bitterfield, Germany. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 2006, 140, 27–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vávra, N. Chemie des Baltischen und Bitterfelder Bernsteins: Methoden, Möglichkeiten, Resultate. In Bitterfelder Bernstein Versus Baltischer Bernstein: Hypothesen, Fakten, Fragen, Proceedings of the II. Bitterfelder Bernsteinkolloquium, Bitterfeld, Germany, 25–27 September 2008; Rascher, J., Wimmer, R., Krumbiegel, G., Schmiedel, S., Eds.; Exkursionsführer und Veröffentlichungen der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Geowissenschaften (EDGG); Mecke: Duderstadt, Germany, 2008; Volume 236, pp. 69–76. [Google Scholar]

- Halbwachs, H.; Clus Bässler, C.; Worobiec, E. Palynomorphs in Baltic, Bitterfeld and Ukrainian ambers: A comparison. Palynology 2021, 45, 441–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alekseev, V.I.; Bukejs, A.; Pollock, D.A. The first fossil of a tenebrionoid taxonomic enigma: Agnathus Germar (Coleoptera: Pyrochroidae: Agnathinae) in Bitterfeld amber, with remarks about age and geographic origin of the fossil. His. Biol. 2025, 37, 714–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drohojowska, J.; Szwedo, J. New Aleyrodidae (Hemiptera: Sternorrhyncha: Aleyrodomorpha) from the Eocene Baltic amber. Pol. J. Entomol. 2011, 80, 659–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnaeus, C. Systema Naturae per Regna Tria Naturae, Secundum Classes, Ordinus, Genera, Species, cum Characteribus, Differentiis, Synonymis, Locis; Editio Decima, Reformata; Tomus Primus, Impensis Direct; Laurentii Salvii: Stockholm, Sweden, 1758; 824p. [Google Scholar]

- Amyot, C.J.-B.; Audinet-Serville, J.G. Deuxième Partie. Homoptères. Homoptera Latr. In Histoire Naturelle des Insects. Hemiptères; Librairie encyclopedique de Roret: Paris, France, 1843; 676p. [Google Scholar]

- Chou, I. Some viewpoints about insect taxonomy. Acta Entomol. Sin. 1963, 12, 586–596. [Google Scholar]

- Westwood, J.O. An Introduction to the Modern Classification of Insects Founded on the Natural Habits and Corresponding Organization of Different Families; Longman, Orme, Brown and Green: London, UK, 1840; Volume 2, pp. i–xi. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffeins, H.W. On the preparation and conservation of amber inclusions in artificial resin. Pol. Pismo Entomol. 2001, 70, 215–219. [Google Scholar]

- Standke, G. Bitterfelder Bernstein gleich Baltischer Bernstein?—Einegeologische Raum-Zeit-Betrachtung und genetische Schlußfolgerungen In Bitterfelder Bernstein Versus Baltischer Bernstein: Hypothesen, Fakten, Fragen, Proceedings of the II. Bitterfelder Bernsteinkolloquium, Bitterfeld, Germany, 25–27 September 2008; Rascher, J., Wimmer, R., Krumbiegel, G., Schmiedel, S., Eds.; Exkursionsführer und Veröffentlichungen der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Geowissenschaften (EDGG); Mecke: Duderstadt, Germany, 2008; Volume 236, pp. 11–33. [Google Scholar]

- Rappsilber, I.; Wendel, A. Bernsteingewinnung aus dem Bernsteinsee bei Bitterfeld und erste wissenschaftliche Ergebnisse. Mauritiana 2019, 37, 87–112. [Google Scholar]

- Suhr, P.; Schneider, W.; Lange, J.M. Facies relationships and depositional environments of the Lausitzer (Lusatic) Tertiary. In 13th IAS Regional Meeting on Sedimentology; Excursion Guide-Book; Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena, Institut für Geowissenschften: Jena, Germany, 1992; pp. 229–260. [Google Scholar]

- Standke, G. Tertiär. In Geologie von Brandenburg; Stackebrandt, W., Franke, D., Eds.; Schweizerbart: Stuttgart, Germany, 2015; pp. 259–323. [Google Scholar]

- Meschede, M. Geologie Deutschlands. Ein Prozessorientierter Ansat; Springer-Verlag GmbH: Stuhr, Germany, 2018; 249p. [Google Scholar]

- Meschede, M.; Warr, L.N. The Geology of Germany. A Process-Oriented Approach; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; 304p. [Google Scholar]

- Standtke, G.; Rascher, J.; Volkman, N. Lowstand cycles and coal formation in paralic environments: New aspects in sequence stratigraphy. In Northern European Cenozoic Stratigraphy, Proceedings of the 8th Biannual Meeting RCNNS/RCNPS, Salzau Castle, Germany, 2–7 October 2002; Gürs, K., Ed.; Landesamt für Natur und Umwelt des Landes Schleswig-Holstein: Flintbek, Germany, 2002; Volume 7, pp. 153–161. [Google Scholar]

- Kus, J.; Dolezych, M.; Schneider, W.; Hofmann, T.; Visiné Rajczi, E. Coal petrological and xylotomical characterization of Miocene lignites and in-situ fossil tree stumps and trunks from Lusatia region, Germany: Palaeoenvironment and taphonomy assessment. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2020, 217, 103283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifert, A.; Brause, H.; Rascher, J. Geology of the Niederlausitz Lignite district, Germany. Int. J. Coal Geol. 1993, 23, 263–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinthorsdottir, M.; Coxall, H.K.; de Boer, A.M.; Huber, M.; Barbolini, N.; Bradshaw, C.D.; Burls, N.J.; Feakins, S.J.; Gasson, E.; Henderiks, J.; et al. The Miocene: The future of the past. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol. 2021, 36, e2020PA004037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kus, J.; Dolezych, M.; Schneider, W.; Hower, J.C.; Hofmann, T.; Visiné Rajcz, E.; Bidló, A.; Bolodár-Varga, B.; Sachsenhofer, R.F.; Bechtel, A.; et al. High-cellulose content of in-situ Miocene fossil tree stumps and trunks from Lusatia lignite mining district, Federal Republic of Germany. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2024, 286, 104494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosmowska-Ceranowicz, B.; Krumbiegel, G. Geologie und Geschichte des Bitterfelder Bernsteins und anderer fossiler Harze. Hallesches Jahrb. Geowiss. 1989, 14, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Krumbiegel, G. Der Bitterfelder Bernstein (Succinite); Lausitzer und Mitteldeutsche Bergbau-Verwaltungsgesellschaft: Bitterfeld, Germany, 1997; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Barthel, M.; Hetzer, H. Bernstein-Inklusen aus dem Miozän des Bitterfelder Raumes. Z. Angew. Geol. 1982, 28, 314–336. [Google Scholar]

- Dubovikoff, D.A.; Dlussky, G.M.; Perkovsky, E.E.; Abakumov, E.V. A new species of the genus Protaneuretus Wheeler (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) from Bitterfeld amber (Late Eocene), with a key to the species of the genus. Paleontol. J. 2020, 54, 389–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbard, P.L.; Lewin, J. Filling the North Sea Basin: Cenozoic sediment sources and river styles. André Dumont medallist lecture 2014. Geol. Belg. 2016, 19, 201–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaes, B.; van Hinsbergen, D.J.J.; van de Lagemaat, S.H.A.; van der Wiel, E.; Lom, N.; Advokaat, E.L.; Boschman, L.M.; Gallo, L.C.; Greve, A.; Guilmette, C.; et al. A global apparent polar wander path for the last 320 Ma calculated from site-level paleomagnetic data. Earth Sci. Rev. 2023, 245, 104547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaes, B.; van Hinsbergen, D.; Paridaens, J. APWP-online.org: A global reference database and open-source tools for calculating apparent polar wander paths and relative paleomagnetic displacements. Tektonika 2024, 2, 174–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuhrmann, R. Die Bernsteinlagerstätte Bitterfeld, nur ein Höhepunkt des Vorkommens von Bernstein (Succinit) im Tertiär Mitteldeutschlands. Z. Dtsch. Ges. Geowiss. 2005, 156, 517–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhmetiev, M.A.; Lopatin, A.V.; Sytchevskaya, E.K.; Popov, S.V. Biogeography of the northern Peri-Tethys from the Late Eocene to the Early Miocene: Part 4. Late Oligocene-Early Miocene: Terrestrial biogeography. Conclusions. J. Paleontol. 2005, 39, S1–S54. [Google Scholar]

- Fuhrmann, R. Der Bernsteinwald im Tertiär Mitteldeutschlands—Auewald versus Sumpfwald. Mauritiana 2011, 22, 61–76. [Google Scholar]

| Measurement (in mm) | Male | Female | Measurement (in mm) | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body length total | 1.03 | 1.15 | Fore wing width | 0.5 | 0.64 |

| Head with compound eyes width | 0.24 | 0.31 | Hind wing length | 0.9 | 1.24 |

| Antennal segment I | 0.02 | 0.03 | Hind wing width | 0.39 | 0.54 |

| Antennal segment II | 0.06 | 0.11 | Profemur length | - | 0.37 |

| Antennal segment III | 0.14 | 0.2 | Protibia length | 0.24 | 0.33 |

| Antennal segment IV | 0.03 | 0.1 | Basiprotarsomere length | 0.09 | 0.13 |

| Antennal segment V | 0.04 | 0.08 | Apical protarsomere length | 0.07 | 0.1 |

| Antennal segment VI | 0.03 | 0.1 | Claws 1 length | 0.02 | - |

| Antennal segment VII | 0.04 | 0.12 | Mesofemur length | - | 0.25 |

| Rostrum length | 0.15 | - | Mesotibia length | 0.27 | 0.37 |

| Pronotum width | 0.26 | 0.35 | Basimesotarsomere length | 0.1 | 0.13 |

| Pronotum length in midline | 0.02 | 0.03 | Apical mesotarsomere length | 0.07 | 0.1 |

| Mesopraescutum width | 0.14 | 0.17 | Claws 2 length | 0.02 | - |

| Mesopraescutum length in midline | 0.08 | 0.14 | Metafemur length | 0.25 | 0.3 |

| Mesoscutum width | 0.27 | 0.35 | Metatibia length | 0.37 | 0.5 |

| Mesoscutum length in midline | 0.03 | 0.05 | Basimetatarsomere length | 0.12 | 0.17 |

| Mesoscutellum width | 0.12 | 0.17 | Apical metatarsomere length | 0.08 | 0.13 |

| Mesoscutellum length | 0.03 | 0.05 | Claws 3 length | 0.02 | - |

| Mesopostnotum width | 0.1 | - | Abdomen length including genitalia | 0.62 | 0.6 |

| Mesopostnotum length | 0.1 | - | Pygofer length | 0.16 | - |

| Metascutum width | 0.24 | 0.13 | Pygofer width | 0.10 | - |

| Metascutum length | 0.04 | - | Claspers length | 0.11 | - |

| Fore wing length | 1.07 | 1.46 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Drohojowska, J.; Gorzelańczyk, A.; Tomanek, N.; Kalandyk-Kołodziejczyk, M.; Szwedo, J. The First Record of Whitefly (Hemiptera, Sternorrhyncha, Aleyrodidae) from Bitterfeld Amber. Insects 2026, 17, 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010050

Drohojowska J, Gorzelańczyk A, Tomanek N, Kalandyk-Kołodziejczyk M, Szwedo J. The First Record of Whitefly (Hemiptera, Sternorrhyncha, Aleyrodidae) from Bitterfeld Amber. Insects. 2026; 17(1):50. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010050

Chicago/Turabian StyleDrohojowska, Jowita, Anita Gorzelańczyk, Natalia Tomanek, Małgorzata Kalandyk-Kołodziejczyk, and Jacek Szwedo. 2026. "The First Record of Whitefly (Hemiptera, Sternorrhyncha, Aleyrodidae) from Bitterfeld Amber" Insects 17, no. 1: 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010050

APA StyleDrohojowska, J., Gorzelańczyk, A., Tomanek, N., Kalandyk-Kołodziejczyk, M., & Szwedo, J. (2026). The First Record of Whitefly (Hemiptera, Sternorrhyncha, Aleyrodidae) from Bitterfeld Amber. Insects, 17(1), 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010050