Coalescent Simulations and Field Experiments Support Natural Selection as the Driving Force Maintaining Color Differences Between Adjacent Populations of Ceroglossus chilensis (Coleoptera: Carabidae)

Simple Summary

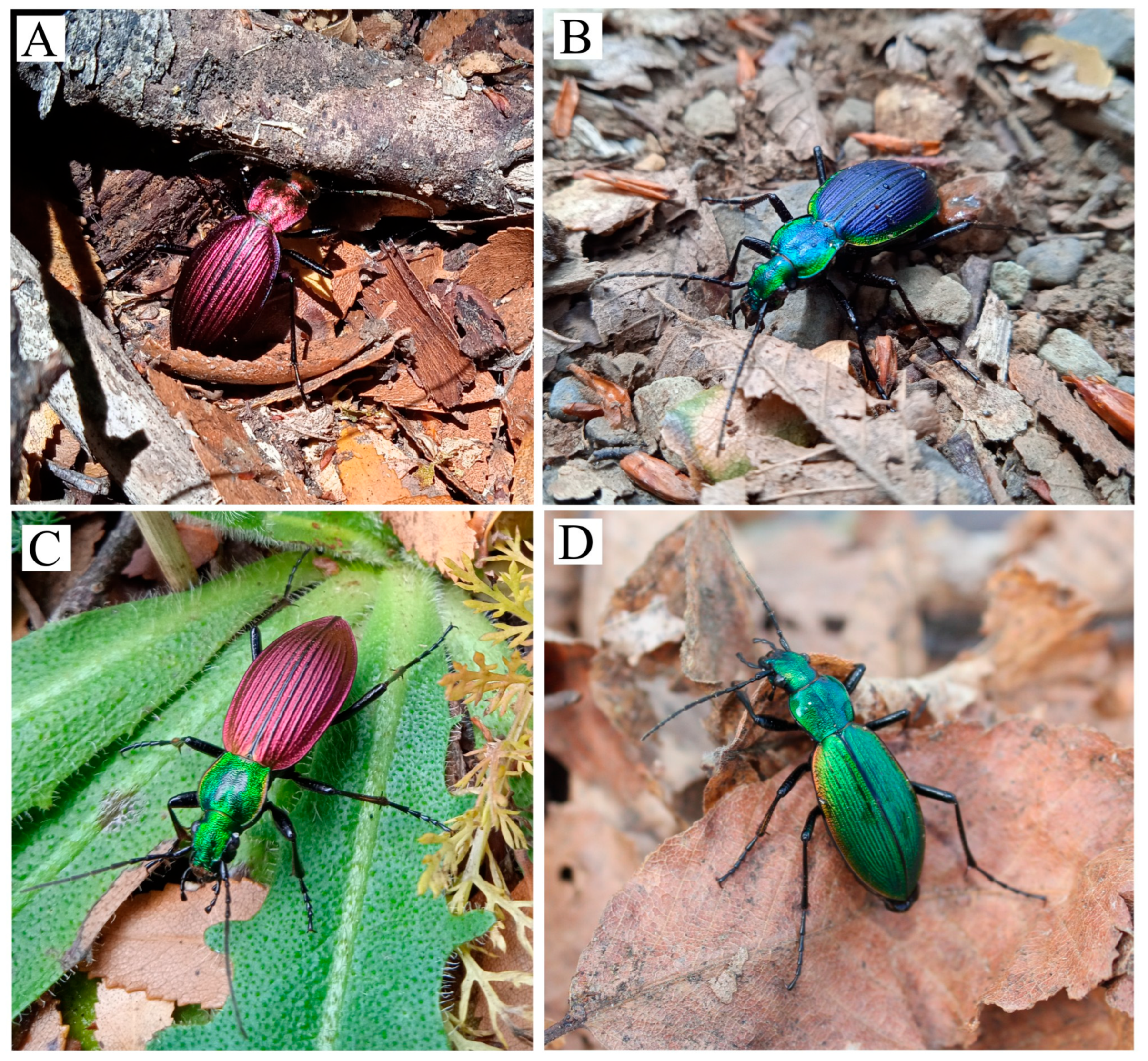

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Coalescent Simulations to Evaluate Genetic Drift

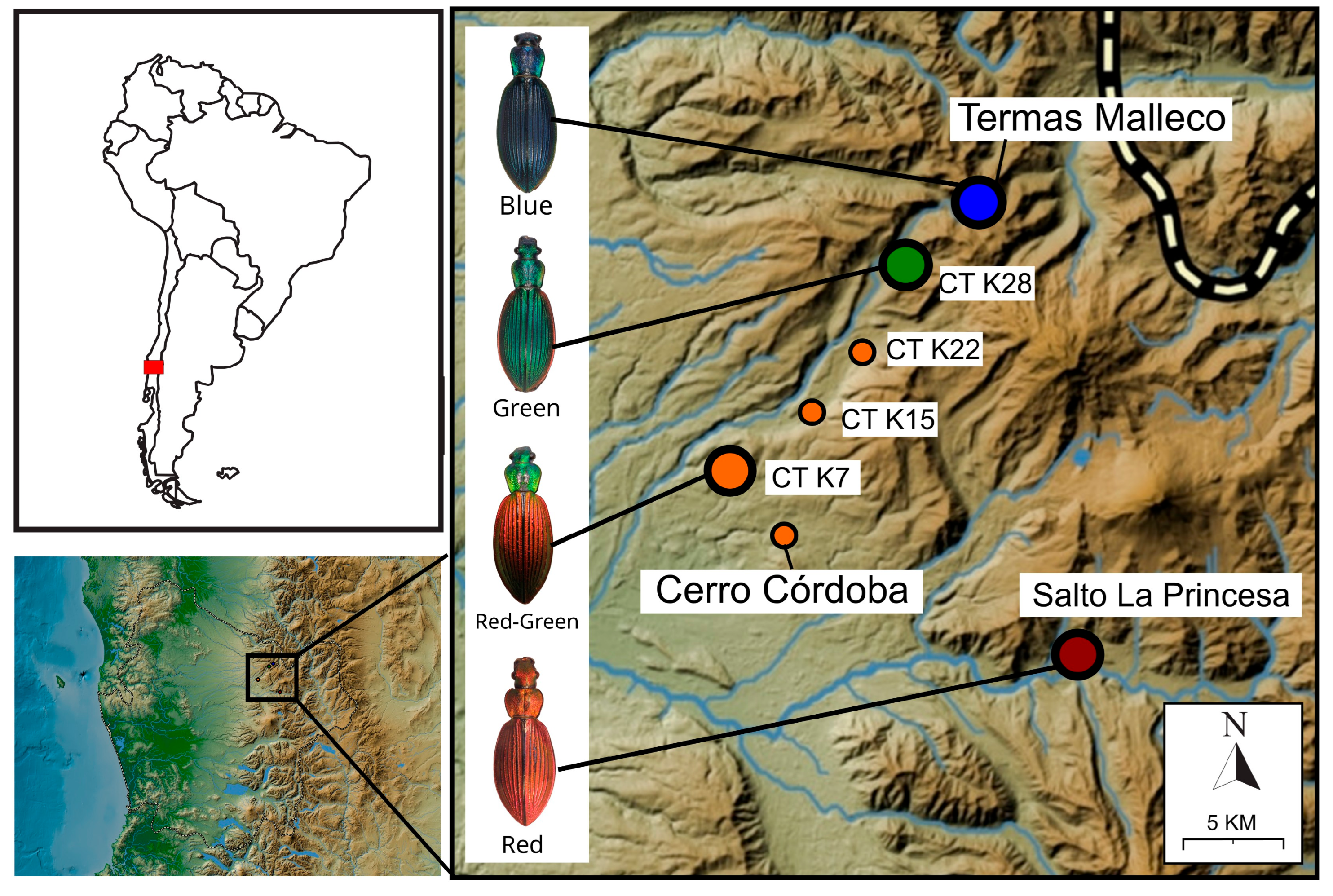

2.1.1. Sampling and Lab Work to Obtain DNA Sequences

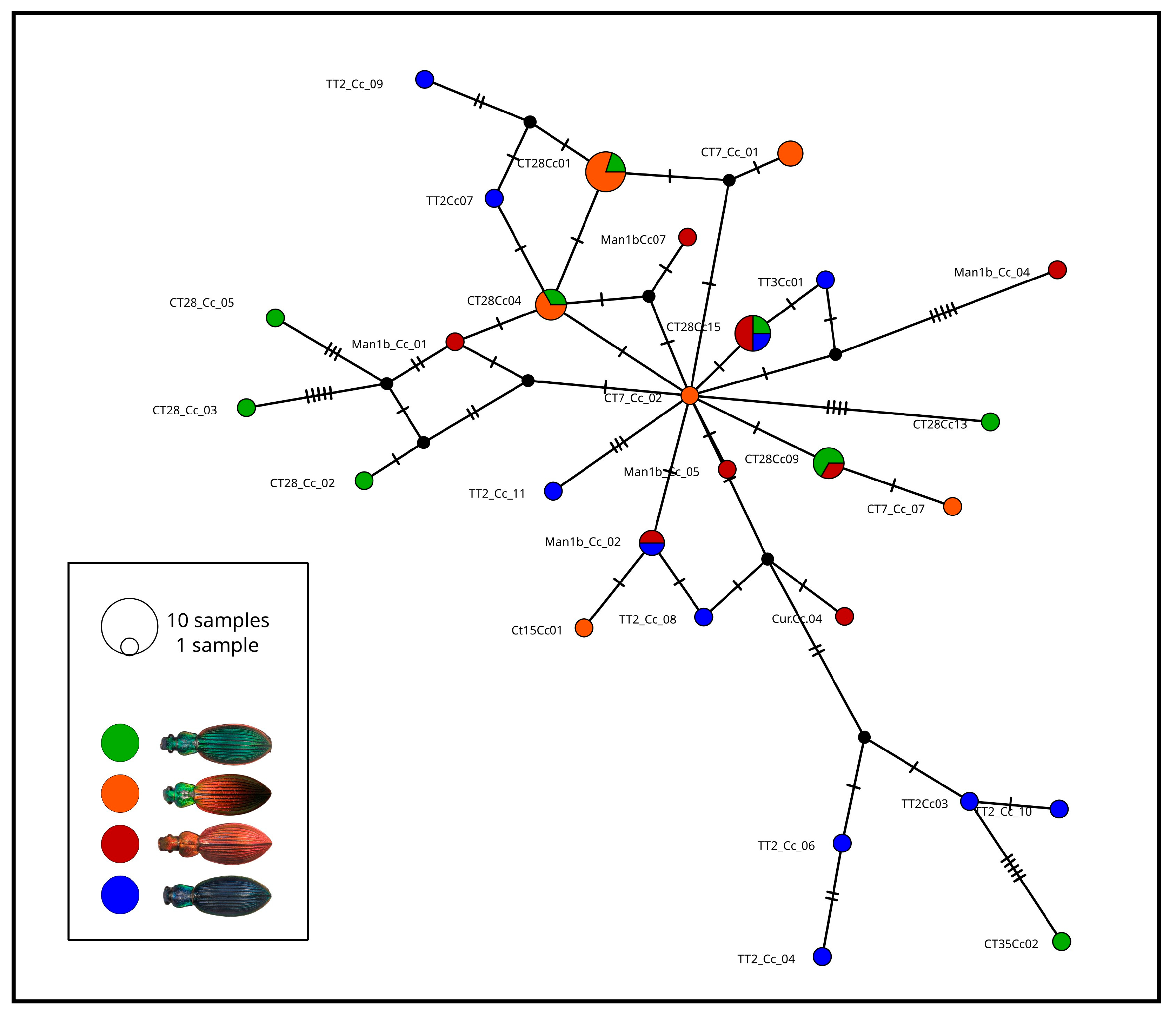

2.1.2. Sequence Editing and Phylogenetic Analyses

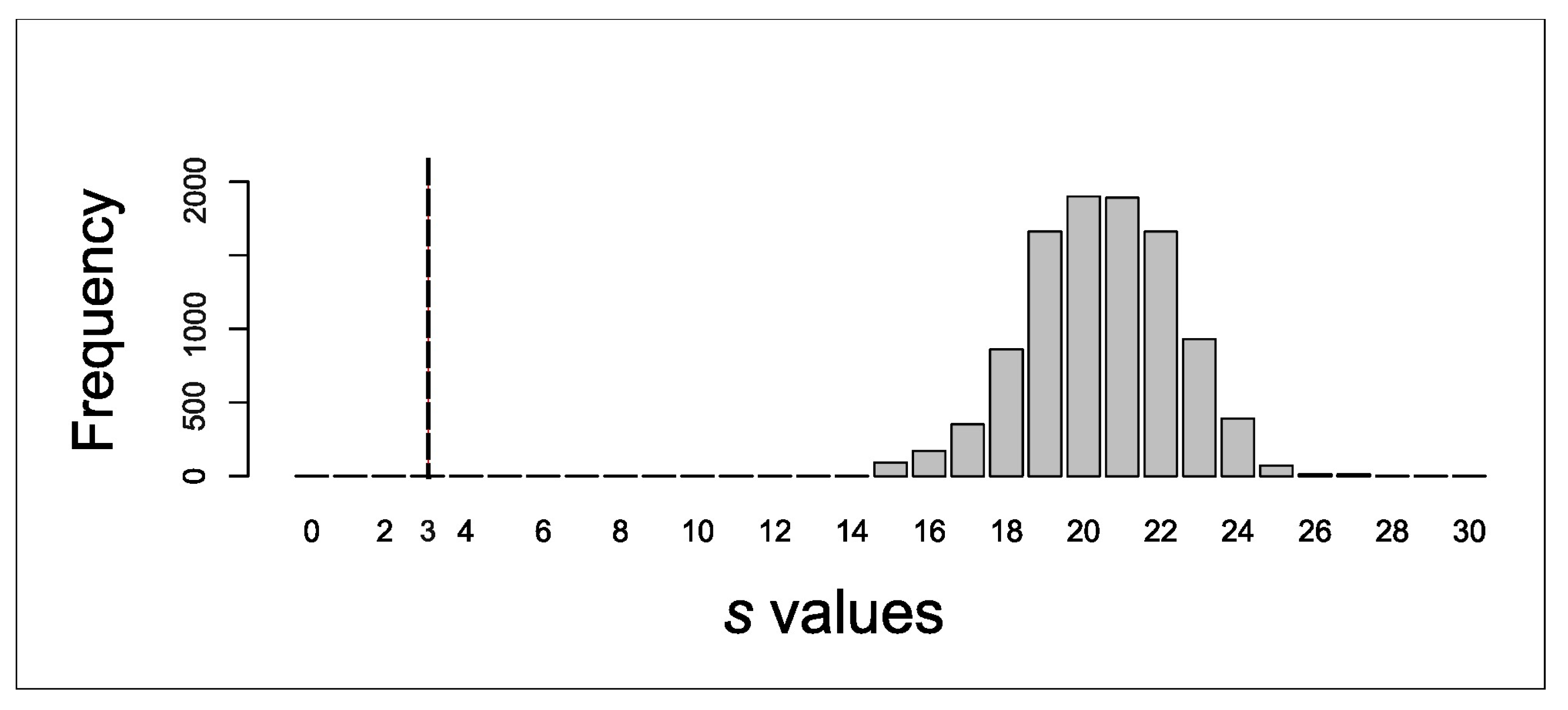

2.1.3. Coalescent Simulation Procedure

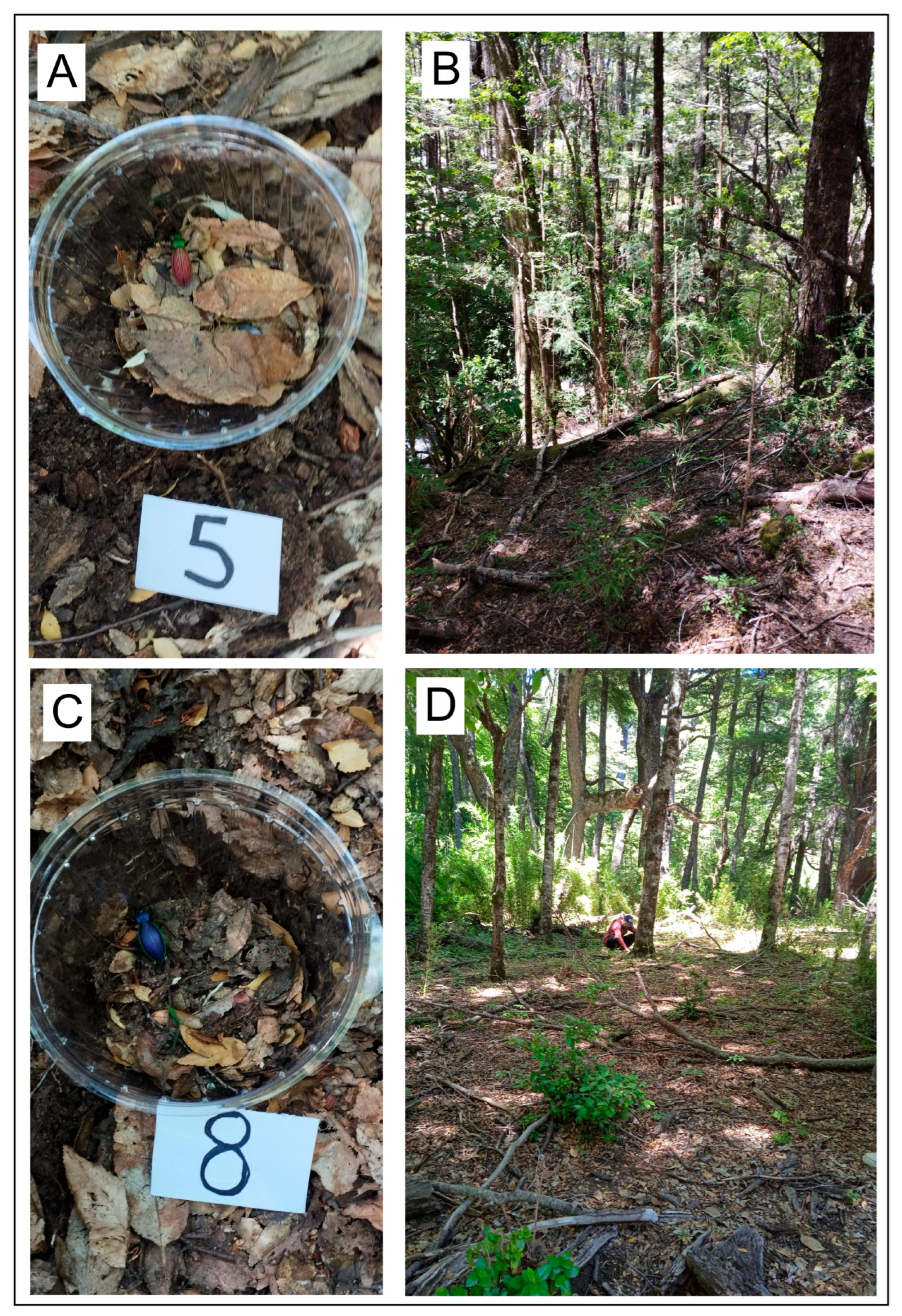

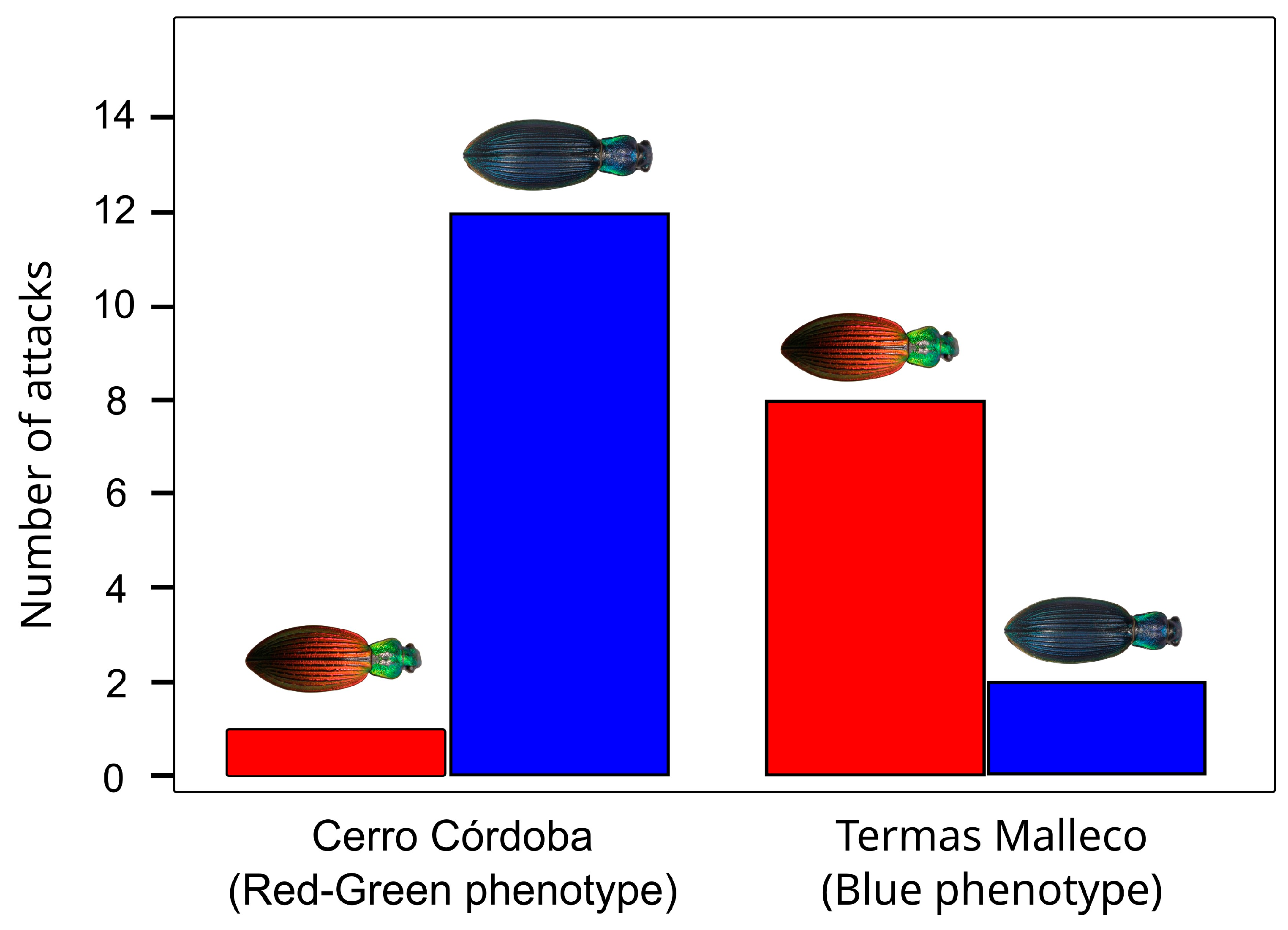

2.2. Predation Experiments to Test Predator Preferences for Different Phenotypes

3. Results

3.1. Genetic and Coalescent Simulation Analyses

3.2. Field Experiments

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pianka, E.R. Evolutionary Ecology; Benjamin-Cummings: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2011; p. 411. [Google Scholar]

- Futuyma, D. Evolution, 3rd ed.; Sinauer Associates, Inc.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2013; p. 656. [Google Scholar]

- Templeton, A.R. Population Genetics and Microevolutionary Theory; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021; p. 705. [Google Scholar]

- Jiroux, E. Le genre Ceroglossus. In Magellanes: Collection Systematique; Magellanes: Bamberg, Germany, 2006; Volume 14, p. 175. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Ramírez, C.P. The Phylogenetic position of Ceroglossus ochsenii GERMAIN and Ceroglossus guerini GERMAIN (Coleoptera: Carabidae), two endemic ground beetles from the Valdivian forest of Chile. Rev. Chil. Entomol. 2015, 40, 14–21. [Google Scholar]

- Benítez, H.A.; Muñoz-Ramírez, C.; Correa, M.; Acuña-Rodríguez, I.S.; Villalobos-Leiva, A.; Contador, T.; Velásquez, N.A.; Suazo, M.J. Breaking the law: Is it correct to use the converse Bergmann Rule in Ceroglossus chilensis? An overview using geometric morphometrics. Insects 2024, 15, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna, A.; Macías, D.; Skigin, D.; Inchaussandague, M.; Schinca, D.; Gigli, M.; Vial, A. Characterization of the iridescence-causing multilayer structure of the Ceroglossus suturalis beetle using bio-inspired optimization strategies. Opt. Express 2013, 21, 19189–19201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasik, B.R.; Liew, S.F.; Lilien, D.A.; Dinwiddie, A.J.; Noh, H.; Cao, H.; Monteiro, A. Artificial selection for structural color on butterfly wings and comparison with natural evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 12109–12114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Y.M.; Kavanaugh, D.H.; Rubio-Perez, B.; Salman, J.; Kats, M.A.; Schoville, S.D. The genomic landscape of metallic color variation in ground beetles. bioRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slatkin, M. Gene flow and genetic drift in a species subject to frequent local extinctions. Theor. Popul. Biol. 1977, 12, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, G.R., Jr.; Pfennig, D.W. Selection overrides gene flow to break down maladaptive mimicry. Nature 2008, 451, 1103–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Errabeli, R.; Will, K.; Arias, E.; Attygalle, A.B. 3-Methyl-1-(methylthio)-2-butene: A component in the foul-smelling defensive secretion of two Ceroglossus species (Coleoptera: Carabidae). Chemoecology 2019, 29, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Ramírez, C.P.; Bitton, P.-P.; Doucet, S.M.; Knowles, L.L. Mimics here and there, but not everywhere: Müllerian mimicry in Ceroglossus ground beetles? Biol. Lett. 2016, 12, 20160429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, M.; Kashiwai, N.; Su, Z.H.; Osawa, S. Sympatric convergence of the color pattern in the Chilean Ceroglossus ground beetles inferred from sequence comparisons of the mitochondrial ND5 gene. J. Mol. Evol. 2001, 53, 530–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-López, A.; Acosta, V.; Rataj, L.; Galián, J. Evolution and diversification of the Southern Chilean genus Ceroglossus (Coleoptera, Carabidae) during the Pleistocene glaciations. Syst. Entomol. 2021, 46, 856–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losos, J.B.; Jackman, T.R.; Larson, A.; Queiroz, K.D.; Rodríguez-Schettino, L. Adaptive Radiations of Island Lizards. Science 1998, 279, 2115–2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brower, A.V. Rapid morphological radiation and convergence among races of the butterfly Heliconius erato inferred from patterns of mitochondrial DNA evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1994, 91, 6491–6495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumbacher, J.P.; Fleischer, R.C. Phylogenetic evidence for colour pattern convergence in toxic pitohuis: Müllerian mimicry in birds? Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 2001, 268, 1971–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, F. Ituna and Thyridia: A remarkable case of mimicry in butterflies. Trans. Entomol. Soc. Lond. 1879, 1879, 20–29. [Google Scholar]

- Chouteau, M.; Arias, M.; Joron, M. Warning signals are under positive frequency-dependence in nature. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 2164–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoddard, M.C. Defensive mimicry and masquerade from the avian visual perspective. Curr. Zool. 2012, 58, 630–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrill, R.M.; Dasmahapatra, K.K.; Davey, J.W.; Dell’Aglio, D.D.; Hanly, J.J.; Huber, B.; Jiggins, J.D.; Joron, M.; Kozak, K.M.; Llaurens, V.; et al. The diversification of Heliconius butterflies: What have we learned in 150 years? J. Evol. Biol. 2015, 28, 1417–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallet, J.; Barton, N.H. Strong Natural Selection in a Warning-Color Hybrid Zone. Evolution 1989, 43, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masta, S.E.; Maddison, W.P. Sexual selection driving diversification in jumping spiders. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 4442–4447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeager, J.; Brown, J.L.; Morales, V.; Cummings, M.; Summers, K. Testing for selection on color and pattern in a mimetic radiation. Curr. Zool. 2012, 58, 668–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folmer, O.; Black, M.; Hoeh, W.; Lutz, R.; Vrijenhoek, R. DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I from diverse metazoan invertebrates. Mol. Mar. Biol. Biotechnol. 1994, 3, 294–299. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Suleski, M.; Sanderford, M.; Sharma, S.; Tamura, K. MEGA12: Molecular Evolutionary Genetic Analysis version 12 for adaptive and green computing. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2024, 41, msae263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlov, A.M.; Darriba, D.; Flouri, T.; Morel, B.; Stamatakis, A. RAxML-NG: A fast, scalable and user-friendly tool for maximum likelihood phylogenetic inference. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 4453–4455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darriba, D.; Posada, D.; Kozlov, A.M.; Stamatakis, A.; Morel, B.; Flouri, T. ModelTest-NG: A new and scalable tool for the selection of DNA and protein evolutionary models. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2020, 37, 291–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leigh, J.W.; Bryant, D.; Nakagawa, S. POPART: Full-feature software for haplotype network construction. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2015, 6, 1110–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Excoffier, L.; Lischer, H.E. Arlequin suite ver 3.5: A new series of programs to perform population genetics analyses under Linux and Windows. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2010, 10, 564–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajima, F. Statistical method for testing the neutral mutation hypothesis by DNA polymorphism. Genetics 1989, 123, 585–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, R. Molecular signatures of natural selection. Ann. Rev. Genet 2005, 39, 197–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddison, W.P. Mesquite: A modular system for evolutionary analysis. Evolution 2008, 62, 1103–1118. [Google Scholar]

- Maddison, W.P.; Slatkin, M. Null models for the number of evolutionary steps in a character on a phylogenetic tree. Evolution 1991, 45, 1184–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024; Available online: https://www.R-project.org (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- Fox, J. Effect displays in R for generalised linear models. J. Stat. Softw. 2003, 8, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrill, R.M.; Wallbank, R.W.; Bull, V.; Salazar, P.C.; Mallet, J.; Stevens, M.; Jiggins, C.D. Disruptive ecological selection on a mating cue. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2012, 279, 4907–4913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkbeiner, S.D. Communal roosting in Heliconius butterflies (Nymphalidae): Roost recruitment, establishment, fidelity, and resource use trends based on age and sex. J. Lepid. Soc. 2014, 68, 10–16. [Google Scholar]

- Chouteau, M.; Angers, B. The role of predators in maintaining the geographic organization of aposematic signals. Am. Nat. 2011, 178, 810–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, A.; Armesto, J.J.; Schlatter, R.P.; Rozzi, R.; Torres-Mura, J.C. La dieta del chucao (Scelorchilus rubecola), un Passeriforme terrícola endémico del bosque templado húmedo de Sudamérica austral. Rev. Chil. Hist. Nat. 1990, 63, 197–202. [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez, J.E.; Jaksic, F.M. Variación estacional de la dieta del caburé grande (Glaucidium nanum) en Chile y su relación con la abundancia de presas. El Hornero 1993, 13, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balza, U.; Lois, N.A.; Polito, M.J.; Pütz, K.; Salom, A.; Raya Rey, A. The dynamic trophic niche of an island bird of prey. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 10, 12264–12276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Rodríguez, E.A.; Ortega-Solís, G.R.; Jimenez, J.E. Conservation and ecological implications of the use of space by chilla foxes and free-ranging dogs in a human-dominated landscape in southern Chile. Austral Ecol. 2010, 35, 765–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Localities | Latitude | Longitude | Phenotype | Vouchers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Termas Malleco | −38.2325 | −71.7283 | Blue | TT2Cc01-04, 6–11; TT3Cc01 |

| Camino Tolhuaca Km. 28 | −38.2611 | −71.7577 | Green | CT28Cc01-05; CT28Cc09,13,15; CT35Cc01-02 |

| Camino Tolhuaca Km. 22 | −38.3072 | −71.7847 | Red-Green | CT22Cc07 |

| Camino Tolhuaca Km. 15 | −38.3478 | −71.8344 | Red-Green | CT15Cc01-04 |

| Camino Tolhuaca Km. 7 | −38.3730 | −71.8984 | Red-Green | CT7Cc01-02, CT7Cc04-07 |

| Cerro Córdoba | −38.4033 | −71.8360 | Red-Green | NA |

| Salto de la Princesa | −38.4747 | −71.6758 | Red | Man1bCc01-05, Man1bCc07-08, Man1bCc10, CurCc04 |

| Phenotypes | Red-Green | Green | Red-Red |

|---|---|---|---|

| Red-Green | |||

| Green | 0.057 * | ||

| Red | 0.124 * | 0.012 | |

| Blue | 0.160 * | 0.056 * | 0.033 |

| Phenotypes | N | S | π | D | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Red-Green | 11 | 7 | 2.14 | −0.415 | 0.361 |

| Green | 10 | 25 | 6.62 | −1.193 | 0.114 |

| Red | 9 | 15 | 3.69 | −1.595 | 0.051 |

| Blue | 11 | 20 | 5.64 | −0.791 | 0.225 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Arenas-Gutierrez, B.; Rivera-Hutinel, A.; Muñoz-Ramírez, C.P. Coalescent Simulations and Field Experiments Support Natural Selection as the Driving Force Maintaining Color Differences Between Adjacent Populations of Ceroglossus chilensis (Coleoptera: Carabidae). Insects 2026, 17, 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010044

Arenas-Gutierrez B, Rivera-Hutinel A, Muñoz-Ramírez CP. Coalescent Simulations and Field Experiments Support Natural Selection as the Driving Force Maintaining Color Differences Between Adjacent Populations of Ceroglossus chilensis (Coleoptera: Carabidae). Insects. 2026; 17(1):44. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010044

Chicago/Turabian StyleArenas-Gutierrez, Benjamín, Antonio Rivera-Hutinel, and Carlos P. Muñoz-Ramírez. 2026. "Coalescent Simulations and Field Experiments Support Natural Selection as the Driving Force Maintaining Color Differences Between Adjacent Populations of Ceroglossus chilensis (Coleoptera: Carabidae)" Insects 17, no. 1: 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010044

APA StyleArenas-Gutierrez, B., Rivera-Hutinel, A., & Muñoz-Ramírez, C. P. (2026). Coalescent Simulations and Field Experiments Support Natural Selection as the Driving Force Maintaining Color Differences Between Adjacent Populations of Ceroglossus chilensis (Coleoptera: Carabidae). Insects, 17(1), 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010044