Hippo and Wnt as Early Initiators: Integrated Multi-Omics Reveals the Signaling Basis for Corona-Induced Diapause Termination in Silkworm

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Silkworm Materials

2.2. RNA Extraction, Library Construction, and Sequencing

2.3. RNA-Seq Data Analysis

2.4. Proteomic

2.5. Function Enrichment Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Corona Treatments Promote the Hatching of Silkworm Eggs

3.2. Transcriptional Changes in Silkworm Eggs After Treatment with Corona

3.3. Trend of DEGs After Treatment with Corona

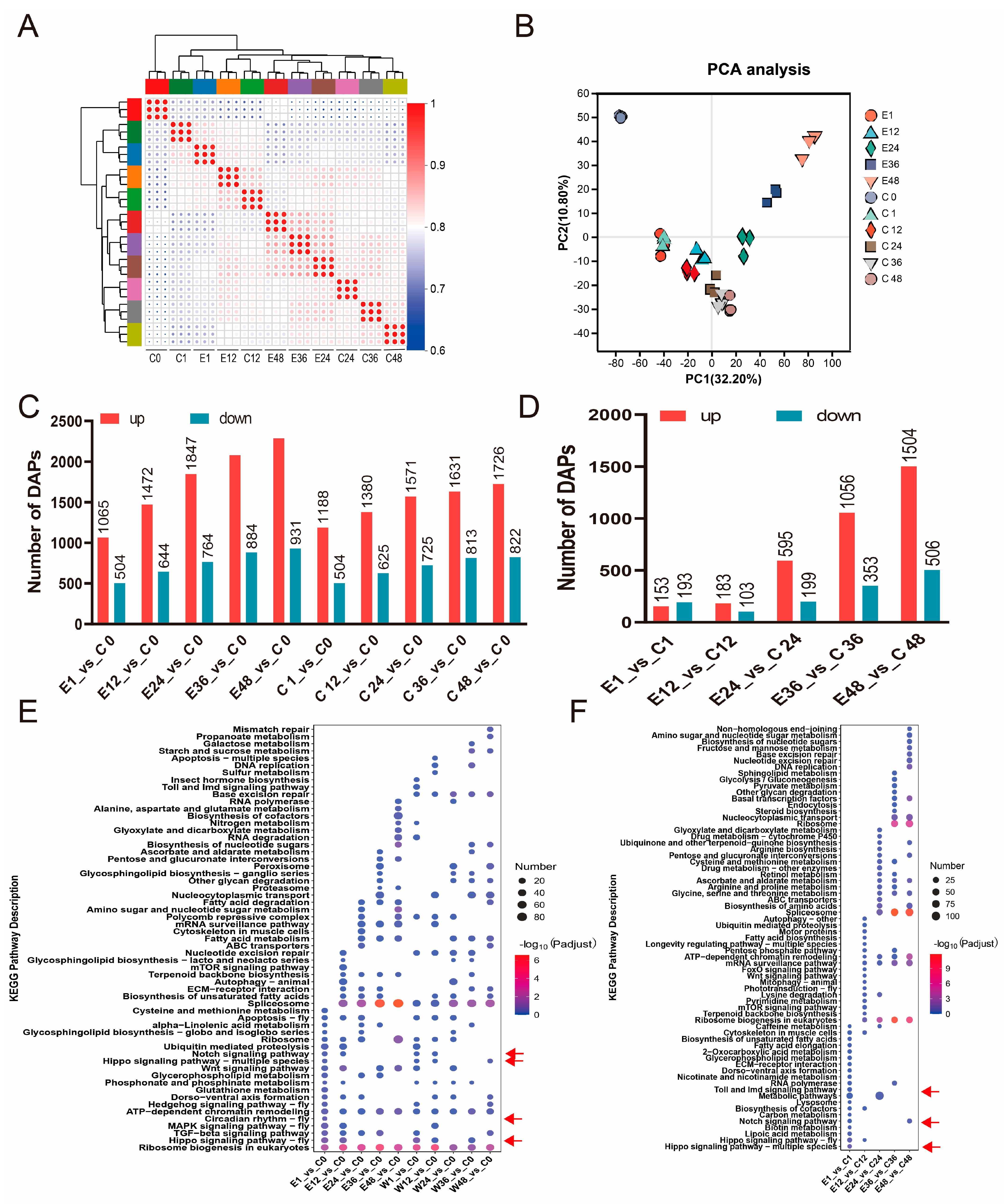

3.4. Protein Content Changes in Silkworm Eggs After Treatment with Corona

3.5. Functional Enrichment of DAPs After Treatment with Corona

3.6. Correlations of Transcriptomic and Proteomic Data

3.7. Hippo and Wnt Signaling Pathways Involved in Embryonic Development

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TPM | Transcripts per million reads |

| DEGs | Differentially expressed genes |

| PAGE | Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis |

| LC-MS/MS | Liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry |

| DIA | Data-independent acquisition |

| DAPs | Differentially abundant proteins |

| FDR | False discovery rate |

| WGCNA | Weighted Gene Co-Expression Network Analysis |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

References

- Hand, S.C.; Denlinger, D.L.; Podrabsky, J.E.; Roy, R. Mechanisms of animal diapause: Recent developments from nematodes, crustaceans, insects, and fish. Am. J. Physiol.-Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2016, 310, R1193–R1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podrabsky, J.E.; Hand, S.C. Physiological strategies during animal diapause: Lessons from brine shrimp and annual killifish. J. Exp. Biol. 2015, 218, 1897–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, H.; Chen, P.; Li, G.; Qiu, F.; Guo, X. Diapause induction in Apolygus lucorum and Adelphocoris suturalis (Hemiptera: Miridae) in northern China. Environ. Entomol. 2012, 41, 1606–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.Y.; Mu, J.Y.; Hu, C.; Wang, H.G. Photoperiodic control of adult diapause in chrysoperla sinica (tjeder) (neuroptera: Chrysopidae) -i. critical photoperiod and sensitive stages of adult diapause induction. Insect Sci. 2004, 11, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Q.; Cheng, D.; Duan, J.; Wang, G.; Cheng, T.; Zha, X.; Liu, C.; Zhao, P.; Dai, F.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Microarray-based gene expression profiles in multiple tissues of the domesticated silkworm, Bombyx mori. Genome Biol. 2007, 8, R162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Q.; Zhou, Z.; Lu, C.; Cheng, D.; Dai, F.; Li, B.; Zhao, P.; Zha, X.; Cheng, T.; Chai, C.; et al. A draft sequence for the genome of the domesticated silkworm (Bombyx mori). Science 2004, 306, 1937–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakagaki, M.; Takei, R.; Nagashima, E.; Yaginuma, T. Cell cycles in embryos of the silkworm, Bombyx mori: G2-arrest at diapause stage. Roux’s Arch. Dev. Biol. 1991, 200, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.Q.; Zhong, Y.S.; Chen, F.Y.; Yan, H.C.; Lin, J.R. Research progress on insect diapause mechanism. Guangdong Agric. Sci. 2014, 20, 81–90. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, J.; Tian, S.; Zhou, X.; Yang, H.; Zhu, Y.; Hou, Y. Transcriptional response of silkworm (Bombyx mori) eggs to O2 or HCl treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.L.; Huang, Y.; Wang, P.Y.; Li, Q.; Bi, L.H.; Zhao, A.C.; Xiang, Z.H.; Long, D.P. Very early corona treatment-mediated artificial incubation of silkworm eggs and germline transformation of diapause silkworm strains. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 843543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, O. Diapause hormone of the silkworm, Bombyx mori: Structure, gene expression and function. J. Insect Physiol. 1996, 42, 669–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akitomo, S.; Egi, Y.; Nakamura, Y.; Suetsugu, Y.; Oishi, K.; Sakamoto, K. Genome-wide microarray screening for Bombyx mori genes related to transmitting the determination outcome of whether to produce diapause or nondiapause eggs. Insect Sci. 2017, 24, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasibhushan, S.; Ponnuvel, K.M.; Vijayaprakash, N.B. Changes in diapause related gene expression pattern during early embryonic development in HCl-treated eggs of bivoltine silkworm Bombyx mori (Lepidoptera: Bombycidae). Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2013, 56, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Lin, J.; Zhong, Y.; Liu, J. Shotgun proteomic analysis on the diapause and non-diapause eggs of domesticated silkworm Bombyx mori. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e60386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Jiang, M.; Wang, P.; Wang, X.; Cui, Q.; Sun, Q. Corona or hydrochloric acid modulates embryonic diapause in silkworms by activating different signaling pathways. PeerJ 2025, 13, e18966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. fastp: An ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, F.; Wei, Z.; Luo, Y.; Guo, H.; Zhang, G.; Xia, Q.; Wang, Y. SilkDB 3.0: Visualizing and exploring multiple levels of data for silkworm. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, D749–D755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.; Paggi, J.M.; Park, C.; Bennett, C.; Salzberg, S.L. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertea, M.; Pertea, G.M.; Antonescu, C.M.; Chang, T.C.; Mendell, J.T.; Salzberg, S.L. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pertea, M.; Kim, D.; Pertea, G.M.; Leek, J.T.; Salzberg, S.L. Transcript-level expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with HISAT, StringTie and Ballgown. Nat. Protoc. 2016, 11, 1650–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Dewey, C.N. RSEM: Accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinform. 2011, 12, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, L.; Futschik, M.E. Mfuzz: A software package for soft clustering of microarray data. Bioinformation 2007, 2, 5–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, E.I.; Weng, S.; Gollub, J.; Jin, H.; Botstein, D.; Cherry, J.M.; Sherlock, G. GO::TermFinder--open source software for accessing Gene Ontology information and finding significantly enriched Gene Ontology terms associated with a list of genes. Bioinformatics 2004, 20, 3710–3715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Furumichi, M.; Sato, Y.; Kawashima, M.; Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG for taxonomy-based analysis of pathways and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D587–D592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.; Jiao, Z.; Yu, F.X. The Hippo signaling pathway in development and regeneration. Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 113926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Xu, M.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, C. The role of Hippo pathway in ovarian development. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1198873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Guan, K.L. Hippo Signaling in Embryogenesis and Development. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2021, 46, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frum, T.; Ralston, A. Visualizing HIPPO Signaling Components in Mouse Early Embryonic Development. Methods Mol. Biol. 2019, 1893, 335–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astone, M.; Tesoriero, C.; Schiavone, M.; Facchinello, N.; Tiso, N.; Argenton, F.; Vettori, A. Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Regulates Yap/Taz Activity during Embryonic Development in Zebrafish. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, W.; Wang, Z.; Hu, W.; Ge, C.; Yuan, W.; Shen, Q.; Li, W.; Chen, W.; Tang, J.; Xiao, Z.; et al. Bexarotene regulates zebrafish embryonic development by activating Wnt signaling pathway. Life Sci. 2025, 373, 123664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurice, M.M.; Angers, S. Mechanistic insights into Wnt-β-catenin pathway activation and signal transduction. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2025, 26, 371–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Beyer, A.; Aebersold, R. On the Dependency of Cellular Protein Levels on mRNA Abundance. Cell 2016, 165, 535–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogel, C.; Marcotte, E.M. Insights into the regulation of protein abundance from proteomic and transcriptomic analyses. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2012, 13, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, X.W.; Xu, W.H. Hexokinase is a key regulator of energy metabolism and ROS activity in insect lifespan extension. Aging 2016, 8, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sun, Q.; Liu, X.; Zhang, G.; Chen, X.; Xie, W.; Wang, P.; Wang, X.; Cui, Q.; Zhang, Y. Hippo and Wnt as Early Initiators: Integrated Multi-Omics Reveals the Signaling Basis for Corona-Induced Diapause Termination in Silkworm. Insects 2026, 17, 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010123

Sun Q, Liu X, Zhang G, Chen X, Xie W, Wang P, Wang X, Cui Q, Zhang Y. Hippo and Wnt as Early Initiators: Integrated Multi-Omics Reveals the Signaling Basis for Corona-Induced Diapause Termination in Silkworm. Insects. 2026; 17(1):123. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010123

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Quan, Xinghui Liu, Guizheng Zhang, Xinxiang Chen, Wenxin Xie, Pingyang Wang, Xia Wang, Qiuying Cui, and Yuli Zhang. 2026. "Hippo and Wnt as Early Initiators: Integrated Multi-Omics Reveals the Signaling Basis for Corona-Induced Diapause Termination in Silkworm" Insects 17, no. 1: 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010123

APA StyleSun, Q., Liu, X., Zhang, G., Chen, X., Xie, W., Wang, P., Wang, X., Cui, Q., & Zhang, Y. (2026). Hippo and Wnt as Early Initiators: Integrated Multi-Omics Reveals the Signaling Basis for Corona-Induced Diapause Termination in Silkworm. Insects, 17(1), 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010123