Transcriptomic Analysis of the Cold Resistance Mechanisms During Overwintering in Apis mellifera

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Preparation

2.2. RNA Sequencing and Analysis

2.3. Bioinformatic Data Processing

2.4. Enzyme Activity Assays

2.5. RT-qPCR Validation

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

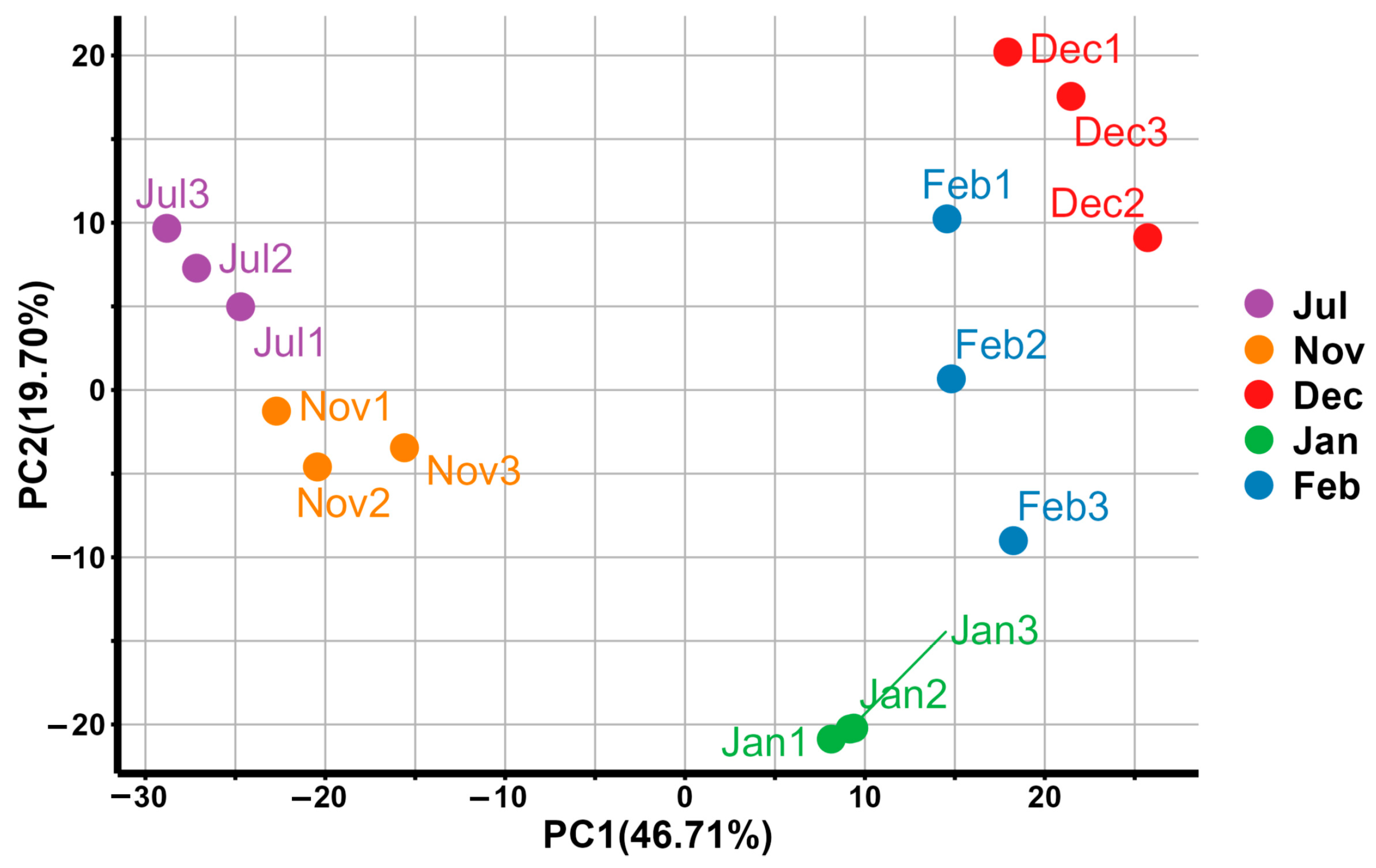

3.1. Comparison of Sequencing Data with the Reference Genome

3.2. Differences in Gene Expression Between Summer and Winter

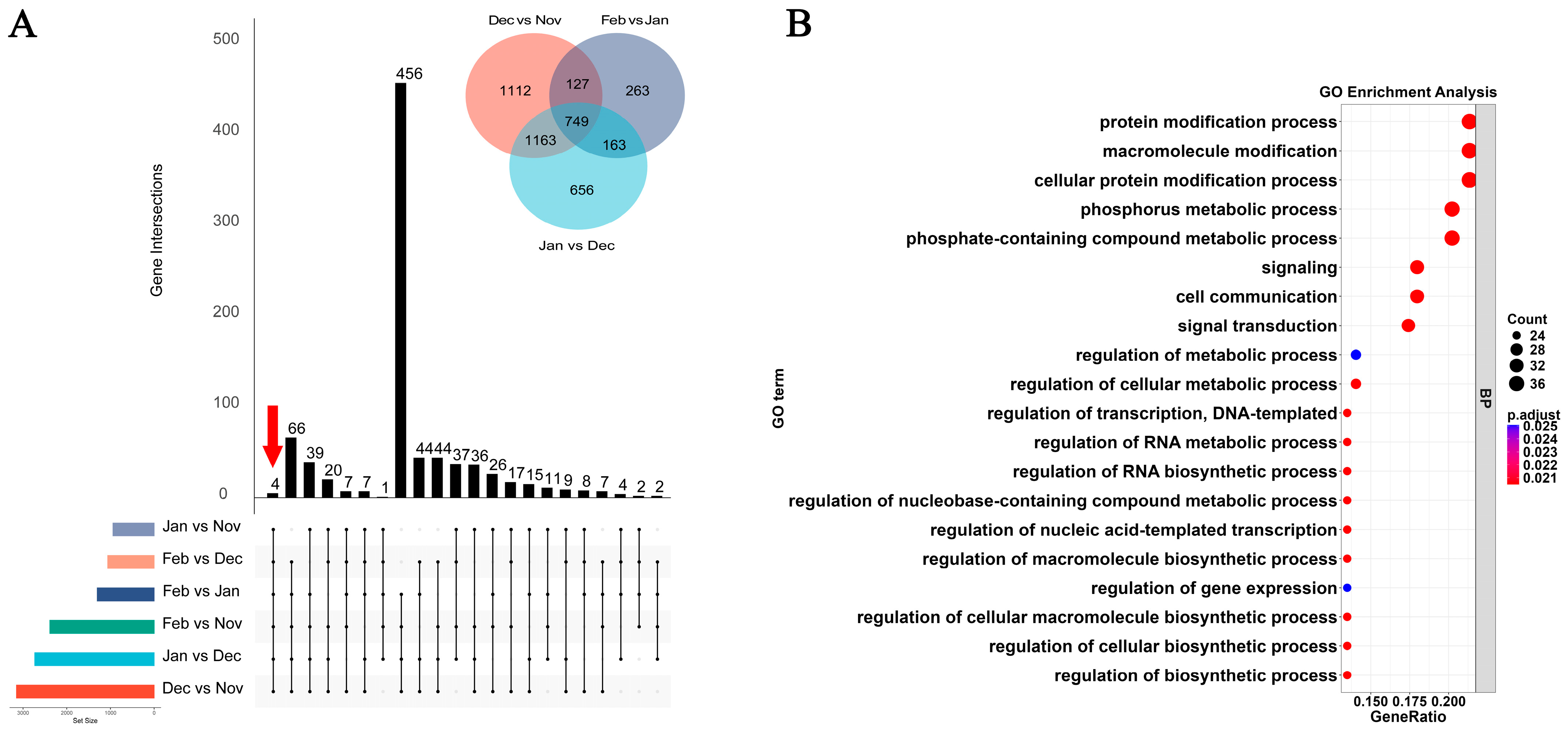

3.3. Shared DEGs Between Four Overwintering Intervals and the Summer Breeding Period

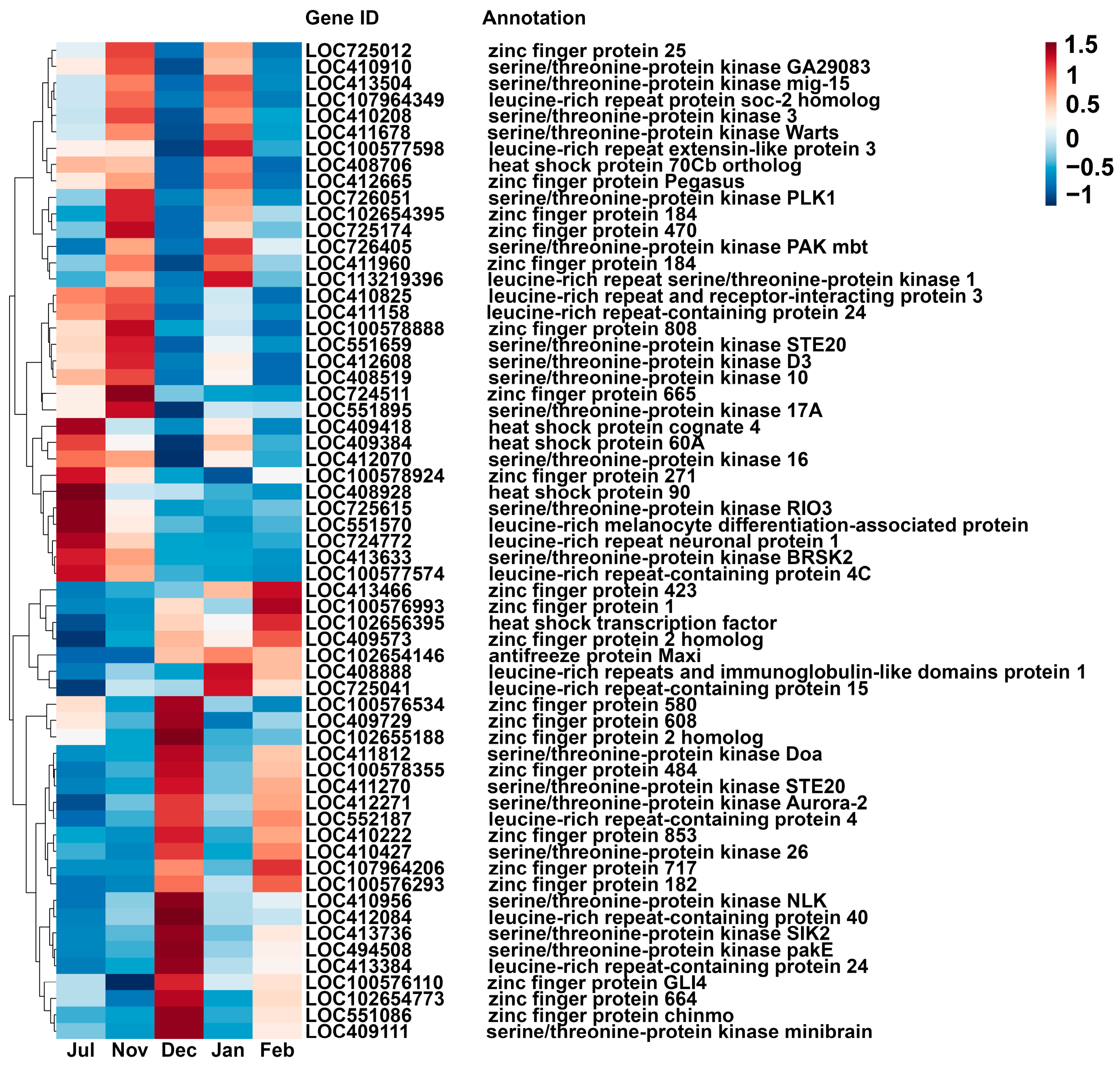

3.4. Identifying DEGs Related to Cold Resistance

3.5. Analysis of Shared DEGs Across Successive Overwintering Intervals

3.6. Shared Gene Set of the Overwintering Period

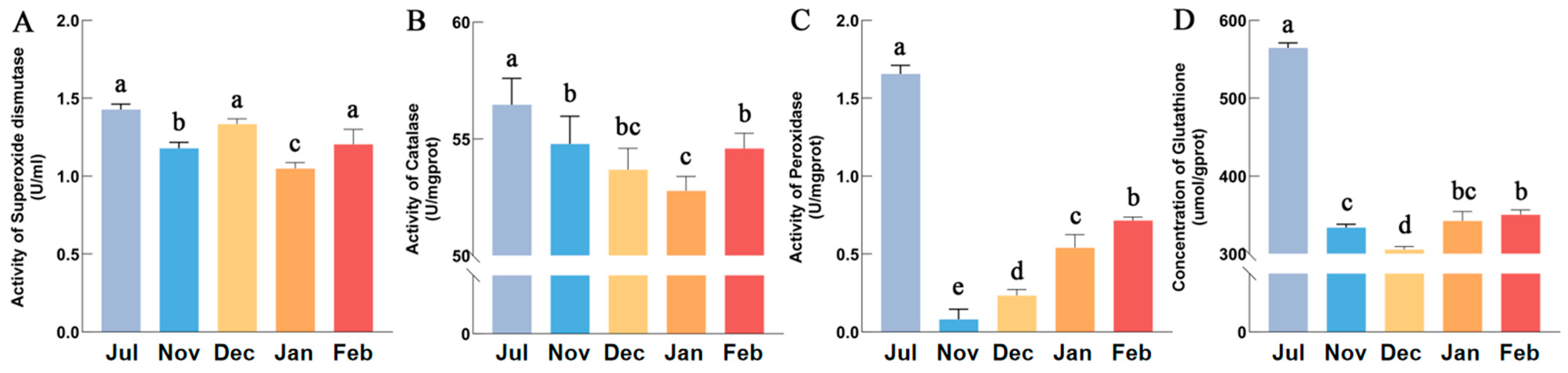

3.7. Antioxidant Capacity Hunchun Bee

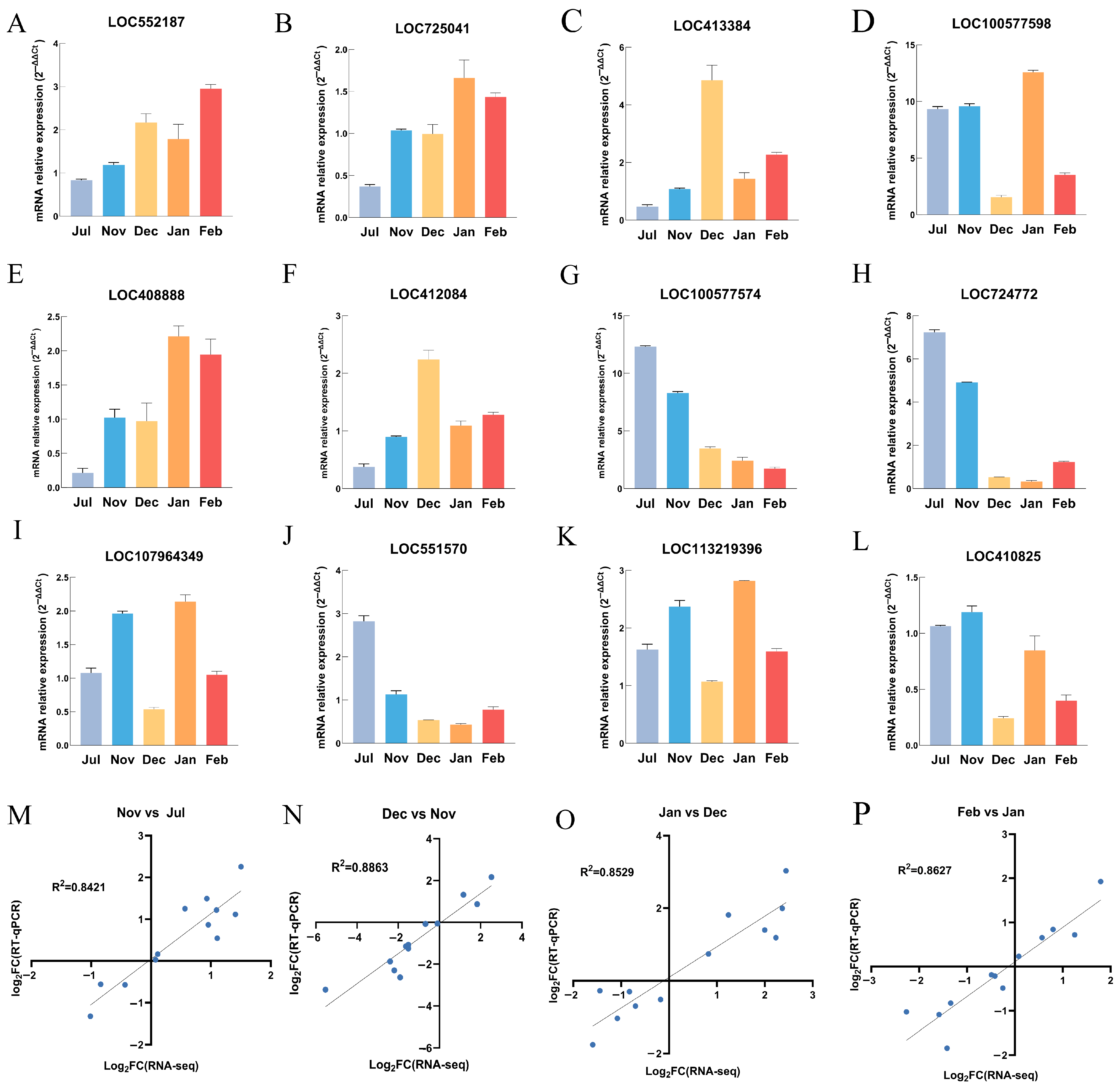

3.8. Verification of Transcriptome Gene

4. Discussion

4.1. Osmoregulatory Capacity Is Critical for Overwintering in Hunchun Bee

4.2. Antioxidant Stress Is Critical for Overwintering in Hunchun Bee

4.3. Fatty Acid Metabolism Degradation Is an Overwintering Strategy of Hunchun Bee

4.4. Expression Regulation of Cold Resistance-Related Protein Genes

4.5. Shared Genes of Hunchun Bee During Overwintering

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kim, H.; Frunze, O.; Lee, J.H.; Kwon, H.W. Enhancing honey bee health: Evaluating pollen substitute diets in field and cage experiments. Insects 2024, 15, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, S.K.; Evans, H.; Meikle, W.G.; Clouston, G. Hive orientation and colony strength affect honey bee colony activity during almond pollination. Insects 2024, 15, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Olhnuud, A.; Tscharntke, T.; Wang, M.; Wu, P.; Xu, H.; Liu, Y. Honeybees interfere with wild bees in apple pollination in China. J. Appl. Ecol. 2025, 62, 801–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, L.M.; Boyle, N.K.; Pitts-Singer, T.L. Osmia lignaria (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae) increase pollination of Washington sweet cherry and pear crops. Environ. Entomol. 2024, 53, 698–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajagopalan, K.; Degrandi-Hoffman, G.; Pruett, M.; Jones, V.P.; Corby-Harris, V.; Pireaud, J.; Curry, R.; Hopkins, B.; Northfield, T.D. Warmer autumns and winters could reduce honey bee overwintering survival with potential risks for pollination services. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 5410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, S.; Pokhrel, L.R.; Akula, S.M.; Ubah, C.S.; Richards, S.L.; Jensen, H.; Kearney, G.D. A scoping review on the effects of Varroa mite (Varroa destructor) on global honey bee decline. Sci. Total. Environ. 2024, 906, 167492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motta, E.V.S.; Moran, N.A. The honeybee microbiota and its impact on health and disease. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2024, 22, 122–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, M.; Bhunia, P.; Shubham; Sen, R.; Bhunia, R.; Gulia, J.; Mondal, T.; Zidane, Z.; Saha, T.; Chacko, A. The impact of weather change on honey bee populations and disease. J. Adv. Zool 2023, 44, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amsalem, E.; Derstine, N.; Murray, C. Hormetic response to pesticides in diapausing bees. Biol. Lett. 2025, 21, 20240612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hristov, P. Biotic and abiotic factors associated with colonies mortalities of managed honey bee (Apis mellifera). Diversity 2019, 11, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skandalis, D.A.; Richards, M.H.; Sformo, T.S.; Tattersall, G.J. Climate limitations on the distribution and phenology of a large carpenter bee, Xylocopa virginica (Hymenoptera: Apidae). Can. J. Zool 2011, 89, 785–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, B.J.; Alvarado, L.E.C.; Ferguson, L.V. An invitation to measure insect cold tolerance: Methods, approaches, and workflow. J. Therm. Biol. 2015, 53, 180–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teets, N.M.; Marshall, K.E.; Reynolds, J.A. Molecular mechanisms of winter survival. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2023, 68, 319–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, M.; Wang, H.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Xu, B. Changes in cold tolerance during the overwintering period in Apis mellifera ligustica. J. Apic. Res. 2019, 58, 702–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teets, N.M.; Denlinger, D.L. Physiological mechanisms of seasonal and rapid cold-hardening in insects. Physiol. Entomol. 2013, 38, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, F.; Abbas, A.; Gul, H.; Güncan, A.; Hafeez, M.; Gadratagi, B.G.; Cicero, L.; Ramirez-Romero, R.; Desneux, N.; Li, Z. Insect resilience: Unraveling responses and adaptations to cold temperatures. J. Appl. Ecol. 2024, 97, 1153–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetty, V.; Adelman, Z.N.; Slotman, M.A. Effects of circadian clock disruption on gene expression and biological processes in Aedes aegypti. BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weger, A.A.; Rittschof, C.C. The diverse roles of insulin signaling in insect behavior. Front. Insect Sci. 2024, 4, 1360320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoll, S.; Pinna, W.; Varcasia, A.; Scala, A.; Cappai, M.G. The honey bee (Apis mellifera L., 1758) and the seasonal adaptation of productions. Highlights on summer to winter transition and back to summer metabolic activity. A review. Livest. Sci. 2020, 235, 104011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Zheng, C.; Shi, F.; Xu, Y.; Zong, S.; Tao, J. Expression analysis of genes related to cold tolerance in Dendroctonus valens. PeerJ 2021, 9, e10864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maigoro, A.Y.; Lee, J.H.; Yun, Y.; Lee, S.; Kwon, H.W. In the battle of survival: Transcriptome analysis of hypopharyngeal gland of the Apis mellifera under temperature-stress. BMC Genom. 2025, 26, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minaud, T.; Rebaudo, F.; Davidson, P.; Hatjina, F.; Hotho, A.; Mainardi, G.; Steffan-Dewenter, I.; Vardakas, P.; Verrier, E.; Requier, F. How stressors disrupt honey bee biological traits and overwintering mechanisms. Heliyon 2024, 10, e34390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, J.; Cheng, R.; Magaoya, T.; Duan, Y.; Chen, C. Comparative Transcriptome analysis of cold tolerance mechanism in honeybees (Apis mellifera sinisxinyuan). Insects 2024, 15, 790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Cao, M.; Li, C.; Zhu, C.; Li, H.; Tian, Y.; Shang, J.; Sun, J.; Zhou, B.; Wu, X.; et al. Biochemical and transcriptomic analysis reveals low temperature-driven oxidative stress in pupal Apis mellifera neural system. Insects 2025, 16, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, K.; Du, Y.; He, J.; Sun, Z.; Jiang, H.; Niu, Q.; Liu, Y.; Su, S. Sequencing and expression characterization of antifreeze protein maxi-like in Apis cerana cerana. J. Insect Sci. 2018, 18, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado, A.; Brunet, J.L.; Peruzzi, M.; Bonnet, M.; Bordier, C.; Crauser, D.; Le Conte, Y.; Alaux, C. Warmer winters are associated with lower levels of the cryoprotectant glycerol, a slower decrease in vitellogenin expression and reduced virus infections in winter honeybees. J. Insect Physiol. 2022, 136, 104348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Ren, Z.; Ren, Q.; Chang, Z.; Li, J.L.; Li, X.; Sun, Z.; He, J.M.; Niu, Q.; Xing, X. Full length transcriptomes analysis of cold-resistance of Apis cerana in Changbai Mountain during overwintering period. Gene 2022, 830, 146503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Q.; Xu, K.; Du, Y.; He, J.; Sun, Z.; Jiang, H.; Niu, Q.; Liu, Y.; Su, S. Expression characteristics of vitellogenin and juvenile hormone in honeybees during overwintering period. J. Environ. Entomol. 2024, 46, 941–947. [Google Scholar]

- China Committee on Animal Genetic Resources. Animal Genetic Resources in China Bees; China Agriculture Press: Beijing, China, 2011; pp. 86–90. [Google Scholar]

- Macmillan, H.A. Dissecting cause from consequence: A systematic approach to thermal limits. J. Exp. Biol. 2019, 222, jeb191593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macmillan, H.A.; Sinclair, B.J. Mechanisms underlying insect chill-coma. J. Insect Physiol. 2010, 57, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosler, J.S.; Burns, J.E.; Esch, H.E. Flight muscle resting potential and species-specific differences in chill-coma. J. Insect Physiol. 2000, 46, 621–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayley, J.S.; Winther, C.B.; Andersen, M.K.; Grnkjr, C.; Nielsen, O.B.; Pedersen, T.H.; Overgaard, J. Cold exposure causes cell death by depolarization-mediated Ca2+ overload in a chill-susceptible insect. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 9737–9744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overgaard, J.; Gerber, L.; Andersen, M.K. Osmoregulatory capacity at low temperature is critical for insect cold tolerance. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2021, 47, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, V.H.; Oyen, K.; Ávila, O.; Ospina, R. Thermal limits of Africanized honey bees are influenced by temperature ramping rate but not by other experimental conditions. J. Therm. Biol. 2022, 110, 103369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Zou, Y.; Zhao, C.; Huang, T.; Jiang, W.; Li, F.; Wu, S. Glutathione-s-transferase regulates oxidative stress in Megalurothrips usitatus in response to environmental stress. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2025, 208, 106299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodrík, D.; Bednářová, A.; Zemanová, M.; Krishnan, N. Hormonal regulation of response to oxidative stress in insects-an update. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 788–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, B.; Le Lann, C.; Hahn, D.A.; Lammers, M.; Nieberding, C.M.; Alborn, H.T.; Enriquez, T.; Scheifler, M.; Harvey, J.A.; Ellers, J. Many parasitoids lack adult fat accumulation, despite fatty acid synthesis: A discussion of concepts and considerations for future research. Curr. Res. Insect Sci. 2023, 3, 100055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowański, S.; Lubawy, J.; Paluch-Lubawa, E.; Gołębiowski, M.; Colinet, H.; Słocińska, M. Metabolism dynamics in tropical cockroach during a cold-induced recovery period. Biol. Res. 2025, 58, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhoseny, M.M.M.; El-Didamony, S.E.; Atwa, W.A.A.; Althoqapy, A.A.; Gouda, H.I.A. New insights into changing honey bee (Apis mellifera) immunity molecules pattern and fatty acid esters, in responses to Ascosphaera apis infection. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2024, 202, 108028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anparasan, L.; Pilecky, M.; Ramirez, M.I.; Hobson, K.A.; Kainz, M.J.; Wassenaar, L.I. Essential and nonessential fatty acid composition and use in overwintering monarch butterflies. J. Comp. Physiol. A 2025, 211, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya-Zeeb, S.; Engelmayer, L.; Straburger, M.; Bayer, J.; Bhre, H.; Seifert, R.; Scherf-Clavel, O.; Thamm, M. Octopamine drives honeybee thermogenesis. Elife 2022, 11, e75334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Wang, M.; Liu, X.; Zhou, K.; Xu, Z.; Zhou, F.; Xu, H. Efficient inhibition of ice recrystallization during frozen storage: Based on the diffusional suppression effect of silk fibroin. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 21763–21771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bale, J.S.; Hayward, S.A.L. Insect overwintering in a changing climate. J. Exp. Biol. 2010, 213, 980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Zhu, Y.; Li, J. Design of eco-friendly antifreeze peptides as novel inhibitors of gas-hydration kinetics. J. Chem. Phys. 2024, 161, 054701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.R.; Wang, C.; Ban, F.X.; Zhu, D.T.; Wang, X.W. Genome-wide identification and characterization of HSP gene superfamily in whitefly (Bemisia tabaci) and expression profiling analysis under temperature stress. Insect Sci. 2019, 26, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fulcher, L.J.; Sapkota, G.P. Functions and regulation of the serine/threonine protein kinase CK1 family: Moving beyond promiscuity. Biochem. J. 2020, 477, 4603–4621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Li, X.; Shen, J.; Du, Y.; Xu, K.; Jiang, Y. Transcriptomic analysis reveals Apis mellifera adaptations to high temperature and high humidity. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 184, 109599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Z.; Wang, T.; Chen, D.; Shen, L.; Zhang, G.; Qian, Q.; Li, Z. Leucine-rich repeat protein family regulates stress tolerance and development in plants. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 32, 32–43. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.J.; Xu, W.; Chen, Q.M.; Sun, L.N.; Anderson, A.; Xia, Q.Y.; Papanicolaou, A. A phylogenomics approach to characterizing sensory neuron membrane proteins (SNMPs) in Lepidoptera. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2020, 118, 103313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso-Junior, C.A.M.; Ronai, I.; Hartfelder, K.; Oldroyd, B.P. Queen pheromone modulates the expression of epigenetic modifier genes in the brain of honeybee workers. Biol. Lett. 2020, 16, 20200440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovegrove, M.R.; Dearden, P.K.; Duncan, E.J. Honeybee queen mandibular pheromone induces a starvation response in Drosophila melanogaster. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2023, 154, 103908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Deng, X.; Du, Y.; Wu, J.; He, J.; Jiang, H.; Liu, Y.; Niu, Q.; Xu, K. Transcriptomic Analysis of the Cold Resistance Mechanisms During Overwintering in Apis mellifera. Insects 2026, 17, 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010059

Deng X, Du Y, Wu J, He J, Jiang H, Liu Y, Niu Q, Xu K. Transcriptomic Analysis of the Cold Resistance Mechanisms During Overwintering in Apis mellifera. Insects. 2026; 17(1):59. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010059

Chicago/Turabian StyleDeng, Xiaoyin, Yali Du, Jiaxu Wu, Jinming He, Haibin Jiang, Yuling Liu, Qingsheng Niu, and Kai Xu. 2026. "Transcriptomic Analysis of the Cold Resistance Mechanisms During Overwintering in Apis mellifera" Insects 17, no. 1: 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010059

APA StyleDeng, X., Du, Y., Wu, J., He, J., Jiang, H., Liu, Y., Niu, Q., & Xu, K. (2026). Transcriptomic Analysis of the Cold Resistance Mechanisms During Overwintering in Apis mellifera. Insects, 17(1), 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010059