Evaluating Real-Time PCR to Quantify Drosophila suzukii Infestation of Fruit Crops

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

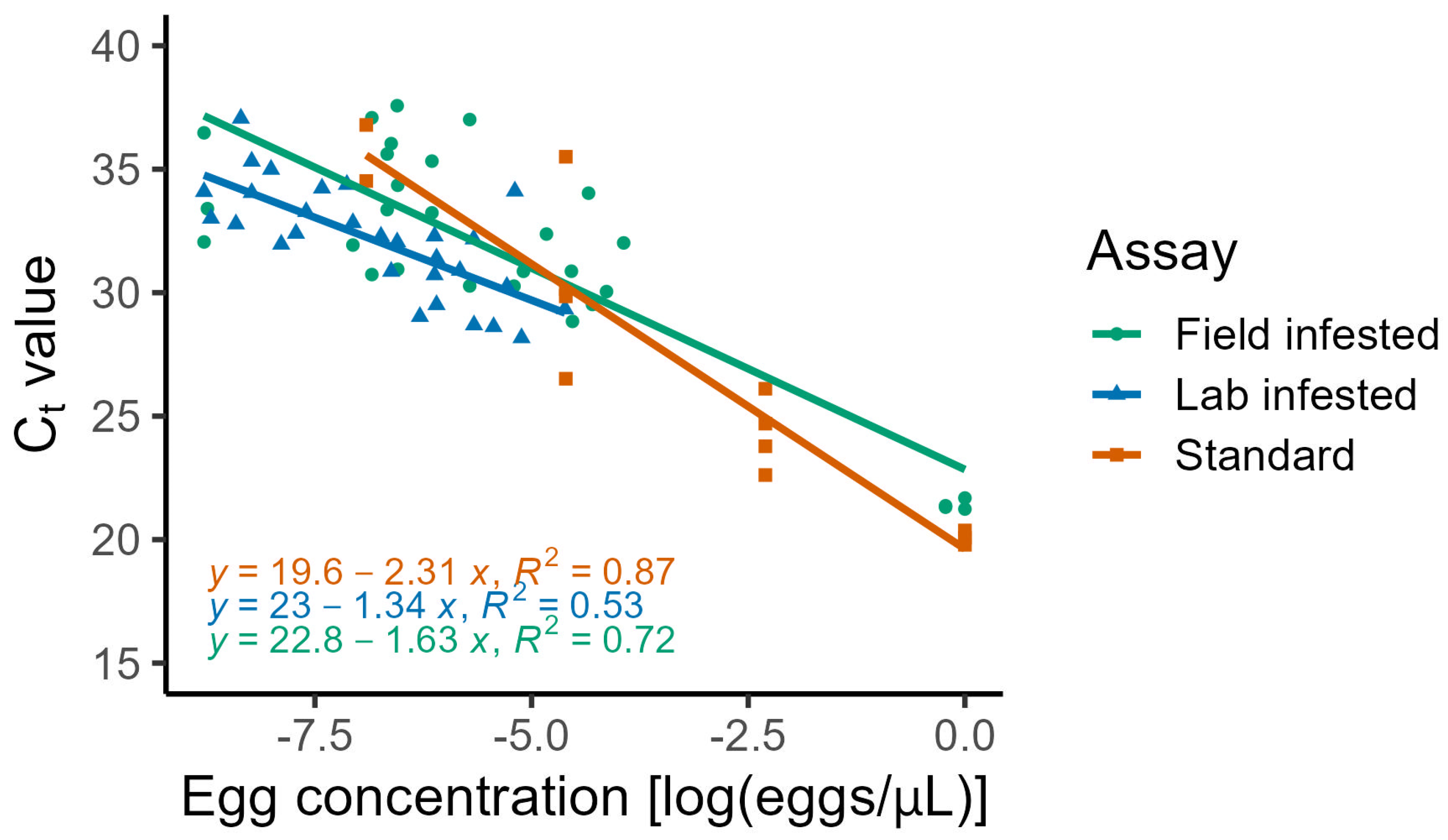

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| qPCR | Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction |

| Ct | Cycle threshold |

| PVP | Polyvinylpyrrolidone |

References

- Venette, R.C.; Hutchison, W.D. Invasive Insect Species: Global Challenges, Strategies & Opportunities. Front. Insect Sci. 2021, 1, 8–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asplen, M.K.; Anfora, G.; Biondi, A.; Choi, D.S.; Chu, D.; Daane, K.M.; Gibert, P.; Gutierrez, A.P.; Hoelmer, K.A.; Hutchison, W.D.; et al. Invasion Biology of Spotted Wing Drosophila (Drosophila suzukii): A Global Perspective and Future Priorities. J. Pest Sci. 2015, 88, 469–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, M. A Historic Account of the Invasion of Drosophila suzukii (Matsumura) (Diptera: Drosophilidae) in the Continental United States, with Remarks on Their Identification. Pest Manag. Sci. 2011, 67, 1352–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cini, A.; Anfora, G.; Escudero-Colomar, L.A.; Grassi, A.; Santosuosso, U.; Seljak, G.; Papini, A. Tracking the Invasion of the Alien Fruit Pest Drosophila suzukii in Europe. J. Pest Sci. 2014, 87, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deprá, M.; Poppe, J.L.; Schmitz, H.J.; De Toni, D.C.; Valente, V.L.S. The First Records of the Invasive Pest Drosophila suzukii in the South American Continent. J. Pest Sci. 2014, 87, 379–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissinen, A.I.; Latvala, S.; Lindqvist, I.; Parikka, P.; Kumpula, R.; Rikala, K.; Blande, J.D. First Observations of Drosophila suzukii (Matsumura) (Diptera: Drosophilidae) Suggest That It Is a Transient Species in Finland. Agric. Food Sci. 2023, 32, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, D.A.; Drummond, F.A.; Gómez, M.I.; Fan, X. The Economic Impacts and Management of Spotted Wing Drosophila (Drosophila suzukii): The Case of Wild Blueberries in Maine. J. Econ. Entomol. 2020, 113, 1262–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burrack, H.J.; Asplen, M.; Bahder, L.; Collins, J.; Drummond, F.A.; Guédot, C.; Isaacs, R.; Johnson, D.; Blanton, A.; Lee, J.C.; et al. Multistate Comparison of Attractants for Monitoring Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae) in Blueberries and Caneberries. Environ. Entomol. 2015, 44, 704–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Timmeren, S.; Diepenbrock, L.M.; Bertone, M.A.; Burrack, H.J.; Isaacs, R. A Filter Method for Improved Monitoring of Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae) Larvae in Fruit. J. Integr. Pest Manag. 2017, 8, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, B.; Cannon, M.F.L.; Buss, D.S.; Cross, J.V.; Brain, P.; Fountain, M.T. Comparison of Extraction Methods for Quantifying Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae) Larvae in Soft- and Stone-Fruits. Crop Prot. 2019, 124, 104868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Timmeren, S.; Davis, A.R.; Isaacs, R. Optimization of Larval Sampling Method for Monitoring Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae) in Blueberries. J. Econ. Entomol. 2021, 114, 1690–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.C.; Shearer, P.W.; Barrantes, L.D.; Beers, E.H.; Burrack, H.J.; Dalton, D.T.; Dreves, A.J.; Gut, L.J.; Hamby, K.A.; Haviland, D.R.; et al. Trap Designs for Monitoring Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae). Environ. Entomol. 2013, 42, 1348–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, H.; Van Timmeren, S.; Wetzel, W.; Isaacs, R. Predicting Within- and between-Year Variation in Activity of the Invasive Spotted Wing Drosophila (Diptera: Drosophilidae) in a Temperate Region. Environ. Entomol. 2019, 48, 1223–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganjisaffar, F.; Abrieux, A.; Gress, B.E.; Chiu, J.C.; Zalom, F.G. Drosophila Infestations of California Strawberries and Identification of Drosophila suzukii Using a TaqMan Assay. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 8783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhami, M.K.; Kumarasinghe, L. A HRM Real-Time PCR Assay for Rapid and Specific Identification of the Emerging Pest Spotted-Wing Drosophila (Drosophila suzukii). PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e98934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y.; Lin, Q.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, X.; Liu, T.; Yu, Y. Identification and Validation of Reference Genes for Quantitative Real-Time PCR in Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae). PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e106800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, K.A.; Unruh, T.R.; Zhou, L.M.; Zalom, F.G.; Shearer, P.W.; Beers, E.H.; Walton, V.M.; Miller, B.; Chiu, J.C. Using Comparative Genomics to Develop a Molecular Diagnostic for the Identification of an Emerging Pest Drosophila suzukii. Bull. Entomol. Res. 2015, 105, 364–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renkema, J.M.; Mcfadden-Smith, W.; Chen, S. Semi-Quantitative Detection of Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae) from Bulk Trap Samples Using PCR Technology. J. Econ. Entomol. 2022, 115, 990–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrader, C.; Schielke, A.; Ellerbroek, L.; Johne, R. PCR Inhibitors—Occurrence, Properties and Removal. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2012, 113, 1014–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heikrujam, J.; Kishor, R.; Behari Mazumder, P. The Chemistry Behind Plant DNA Isolation Protocols. In Biochemical Analysis Tools—Methods for Bio-Molecules Studies; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2020; Volume 11, p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Dalton, D.T.; Walton, V.M.; Shearer, P.W.; Walsh, D.B.; Caprile, J.; Isaacs, R. Laboratory Survival of Drosophila suzukii under Simulated Winter Conditions of the Pacific Northwest and Seasonal Field Trapping in Five Primary Regions of Small and Stone Fruit Production in the United States. Pest Manag. Sci. 2011, 67, 1368–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schierenbeck, K.A. Modified Polyethylene Glycol DNA Extraction Procedure for Silica Gel-Dried Tropical Woody Plants. BioTechniques 1994, 16, 392–394. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team R. A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Gullickson, M.; Hodge, C.F.; Hegeman, A.; Rogers, M. Deterrent Effects of Essential Oils on Spotted-Wing Drosophila (Drosophila suzukii): Implications for Organic Management in Berry Crops. Insects 2020, 11, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markow, T.A.; Beall, S.; Matzkin, L.M. Egg Size, Embryonic Development Time and Ovoviviparity in Drosophila Species. J. Evol. Biol. 2009, 22, 430–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Lakonishok, M.; Gelfand, V.I. The Dynamic Duo of Microtubule Polymerase Mini Spindles/XMAP215 and Cytoplasmic Dynein Is Essential for Maintaining Drosophila Oocyte Fate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2303376120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gullickson, M.G.; Digiacomo, G.; Rogers, M.A. Efficacy and Economic Viability of Organic Control Methods for Spotted-Wing Drosophila in Day-Neutral Strawberry Production in the Upper Midwest. HortTechnology 2024, 34, 618–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullickson, M.G.; Rogers, M.A.; Burkness, E.C.; Hutchison, W.D. Efficacy of Organic and Conventional Insecticides for Drosophila suzukii When Combined with Erythritol, a Non-Nutritive Feeding Stimulant. Crop Prot. 2019, 125, 104878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gullickson, M.G.; Averello, V., IV; Rogers, M.A.; Hutchison, W.D.; Hegeman, A. Evaluating Real-Time PCR to Quantify Drosophila suzukii Infestation of Fruit Crops. Insects 2026, 17, 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010102

Gullickson MG, Averello V IV, Rogers MA, Hutchison WD, Hegeman A. Evaluating Real-Time PCR to Quantify Drosophila suzukii Infestation of Fruit Crops. Insects. 2026; 17(1):102. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010102

Chicago/Turabian StyleGullickson, Matthew G., Vincenzo Averello, IV, Mary A. Rogers, William D. Hutchison, and Adrian Hegeman. 2026. "Evaluating Real-Time PCR to Quantify Drosophila suzukii Infestation of Fruit Crops" Insects 17, no. 1: 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010102

APA StyleGullickson, M. G., Averello, V., IV, Rogers, M. A., Hutchison, W. D., & Hegeman, A. (2026). Evaluating Real-Time PCR to Quantify Drosophila suzukii Infestation of Fruit Crops. Insects, 17(1), 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010102