In Vitro Termiticidal Activity of Medicinal Plant Essential Oils Against Microcerotermes crassus

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Essential Oils, Reference Compound, and Preparation

2.2. Stock and Working Solutions

2.3. Termite Collection and Maintenance

2.4. Chemical Characterization of Essential Oils

2.5. Contact Toxicity Bioassays

2.5.1. Screening Bioassays

2.5.2. Toxicity Assays (Contact-Residue Under Sealed-Dish Conditions, Follow-Up to Screening)

2.6. Repellency Bioassays

2.7. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Screening and Chemical Composition of Essential Oils

3.2. Contact Toxicity and Lethal Time of Essential Oils

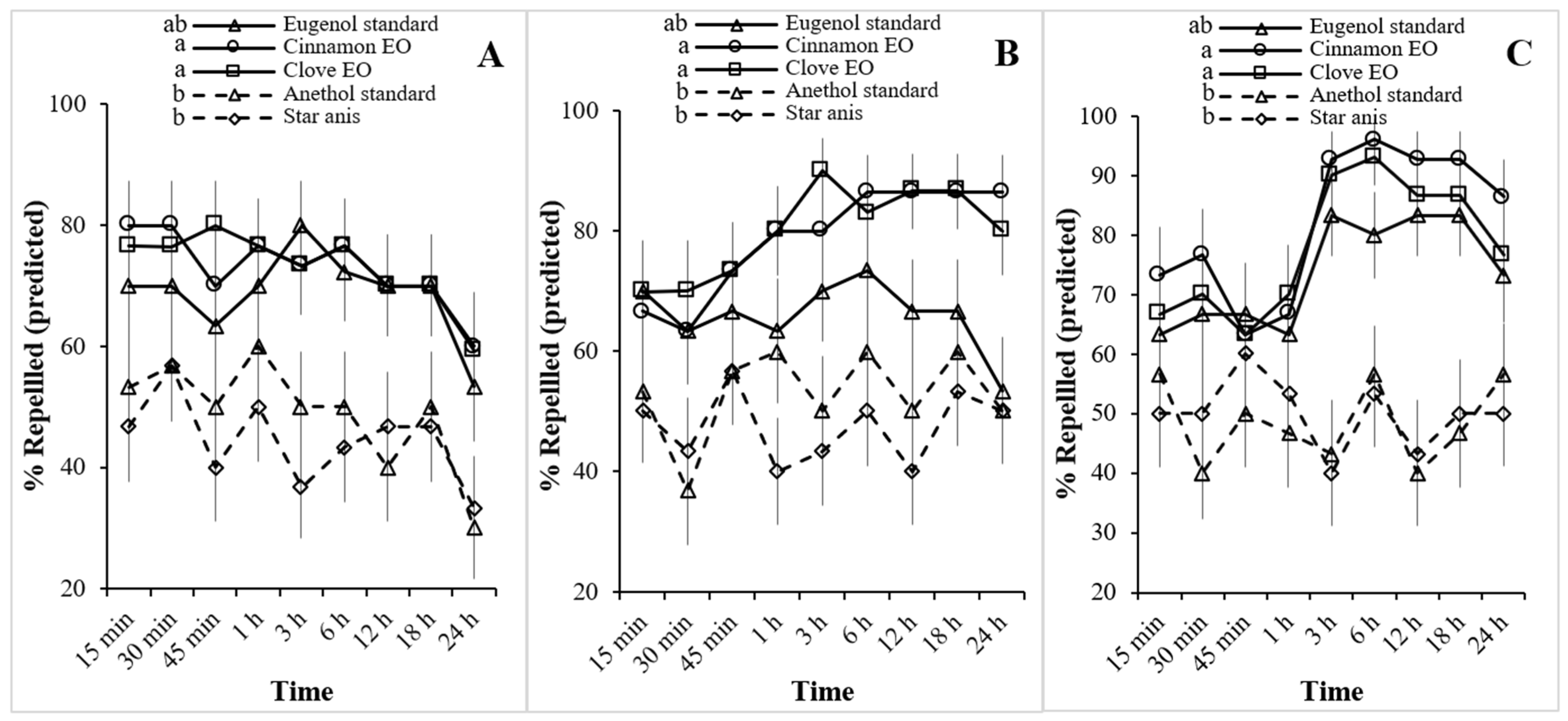

3.3. Repellent Activity of Essential Oils

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Krishna, K.; Grimaldi, D.A.; Krishna, V.; Engel, M.S. Treatise on the Isoptera of the world. Volume 1: Introduction. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 2013, 377, 1–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rust, M.K.; Su, N.-Y. Managing social insects of urban importance. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2012, 57, 355–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, T.A.; Forschler, B.T.; Grace, J.K. Biology of invasive termites: A worldwide review. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2013, 58, 455–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lertlumnaphakul, W.; Ngoen-Klan, R.; Vongkaluang, C.; Chareonviriyaphap, T.A. Review of termite species and their distribution in Thailand. Insects 2022, 13, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouquet, P.; Traoré, S.; Choosai, C.; Hartmann, C.; Bignell, D. Influence of termites on ecosystem functioning: Ecosystem services provided by termites. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2011, 47, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-Y.; Vongkaluang, C.; Lenz, M. Challenges to subterranean termite management of multi-genera faunas in Southeast Asia and Australia. Sociobiology 2007, 50, 213–221. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.-C.; Neoh, K.-B.; Lee, C.-Y. Caste composition and mound size of the subterranean termite Macrotermes gilvus. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 2012, 105, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vongkaluang, C.; Charoenkrung, K.; Sornnuwat, Y. Field trials in Thailand on the efficacy of some soil termiticides to prevent subterranean termites. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Urban Pests, Singapore, 11–13 July 2005; pp. 251–256. [Google Scholar]

- Katsuda, Y.; Minamite, Y.; Vongkaluang, C. Development of silafluofen-based termiticides in Japan and Thailand. Insects 2011, 2, 532–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-C.; Neoh, K.-B.; Lee, C.-Y. Colony size affects the efficacy of bait containing chlorfluazuron against Macrotermes gilvus. J. Econ. Entomol. 2014, 107, 2154–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunasekara, A.S.; Truong, T.; Goh, K.S.; Spurlock, F.; Tjeerdema, R.S. Environmental fate and toxicology of fipronil. J. Pestic. Sci. 2007, 32, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agriculture and Environment Research Unit (AERU). Cypermethrin (Ref: OMS 2002). In Pesticide Properties DataBase (PPDB); Agriculture and Environment Research Unit (AERU), University of Hertfordshire: Hatfield, UK, 2025; Available online: https://sitem.herts.ac.uk/aeru/ppdb/en/Reports/197.htm (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Peer review of the pesticide risk assessment of the active substance cypermethrin. EFSA J. 2018, 16, e05402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weston, D.P.; Lydy, M.J. Toxicity of the insecticide fipronil and its degradates to benthic macroinvertebrates of urban streams. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 1290–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maund, S.J.; Hamer, M.J.; Lane, M.C.G.; Farrelly, E.; Rapley, J.H.; Goggin, U.M.; Gentle, W.E. Partitioning, bioavailability, and toxicity of the pyrethroid insecticide cypermethrin in sediments. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2002, 21, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suchail, S.; Guez, D.; Belzunces, L.P. Discrepancy between acute and chronic toxicity induced by imidacloprid and its metabolites in Apis mellifera. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2001, 20, 2482–2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Bayo, F.; Goka, K. Pesticide residues and bees—A risk assessment. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e94482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, G.L.; Roebuck, J.; Moore, C.B.; Waldvogel, M.G.; Schal, C. Origin and extent of resistance to fipronil in the German cockroach, Blattella germanica (L.) (Dictyoptera: Blattellidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 2003, 96, 1548–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, M.; Hansen, K.K.; Jensen, K.-M.V. Cross-resistance between dieldrin and fipronil in German cockroach (Dictyoptera: Blattellidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 2005, 98, 1305–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gondhalekar, A.D.; Scharf, M.E. Mechanisms underlying fipronil resistance in a multiresistant field strain of the German cockroach (Blattodea: Blattellidae). J. Med. Entomol. 2012, 49, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isman, M.B. Botanical insecticides, deterrents, and repellents in modern agriculture and increasingly regulated world. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2006, 51, 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regnault-Roger, C.; Vincent, C.; Arnason, J.T. Essential oils in insect control: Low-risk products in a high-stakes world. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2012, 57, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavela, R.; Benelli, G. Essential oils as eco-friendly biopesticides? Challenges and constraints. Trends Plant Sci. 2016, 21, 1000–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Du, C.; Duan, B.; Wang, W.; Guo, H.; Feng, J.; Xu, H.; Li, Y. Eugenol exposure inhibits embryonic development and swim bladder formation in zebrafish. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C: Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2023, 268, 109602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramod, G.N.; Ashwini, S.; Rao, P.J.; Priyadarshini, P. Assessment of acute and subacute toxicity, pharmacokinetics, and biodistribution of eugenol nanoparticles after oral exposure in Wistar rats. Nanotoxicology 2024, 18, 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Isman, M.B.; Tak, J.-H. Insecticidal activity of 28 essential oils and a commercial product containing Cinnamomum cassia bark essential oil against Sitophilus zeamais Motschulsky. Insects 2020, 11, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, V.K.; Srivastava, S.; Ashish Dash, K.K.; Singh, R.; Dar, A.H.; Singh, T.; Farooqui, A.; Shaikh, A.M.; Kovacs, B. Bioactive properties of clove (Syzygium aromaticum) essential oil nanoemulsion: A comprehensive review. Heliyon 2023, 10, e22437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plata-Rueda, A.; Campos, J.M.; da Silva Rolim, G.; Martínez, L.C.; Dos Santos, M.H.; Fernandes, F.L.; Serrão, J.E.; Zanuncio, J.C. Terpenoid constituents of cinnamon and clove essential oils cause toxic effects and behavior repellency response on granary weevil, Sitophilus granarius. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2018, 156, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adfa, M.; Livandri, F.; Meita, N.P.; Manaf, S.; Ninomiya, M.; Gustian, I.; Koketsu, M. Termiticidal activity of Acorus calamus Linn. rhizomes and its main constituents against Coptotermes curvignathus Holmgren. J. Asia-Pac. Entomol. 2015, 18, 47–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.S.; Ahn, Y.J. Fumigant activity of (E)-anethole from Illicium verum against Blattella germanica. Pest Manag. Sci. 2002, 58, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, L.; Hua, R.; Li, M.; Huang, Y.; Li, S.; He, Y.; Shen, Z. Chemical composition and biological activity of star anise (Illicium verum) extracts against maize weevil, Sitophilus zeamais adults. J. Insect Sci. 2014, 14, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pumnuan, J.; Sarapothong, K.; Sikhao, P.; Pattamadilok, C.; Insung, A. Film seeds coating with hexane extracts from Illicium verum Hook. f. and Syzygium aromaticum (L.) Merrill & Perry for controlling Callosobruchus maculatus (F.) and Callosobruchus chinensis L. Pest Manag. Sci. 2021, 77, 2512–2521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, I.K.; Shin, S.C. Fumigant activity of plant essential oils and components from garlic (Allium sativum) and clove bud (Eugenia caryophyllata) oils against the Japanese termite (Reticulitermes speratus Kolbe). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 4388–4392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, S.-S.; Liu, J.-Y.; Hsui, Y.-R.; Chang, S.-T. Anti-termitic activities of essential oils from coniferous trees against Coptotermes formosanus. Bioresour. Technol. 2007, 98, 456–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pumnuan, J.; Insung, A.; Klompanya, A. Effects of seven plant essential oils on mortalities of chicken lice (Lipeurus caponis L.) Adult. Curr. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2020, 20, 52–58. [Google Scholar]

- Ruddit, A.; Pumnuan, J.; Lakyat, A.; Doungnapa, T.; Thipmanee, K. Effectiveness of Kratom (Mitragyna speciosa Korth) leaf extracts against adult of sweet potato weevil (Cylas formicarius Fabricius) in laboratory conditions. Int. J. Agric. Technol. 2024, 20, 1227–1236. [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara, R.B.; Kotze, D.J. Do not log-transform count data. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2010, 1, 118–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stutz, R.S.; Chu, C.C.; Morrison, W.R. Using statistical models to analyze repellency bioassays. Insects 2019, 10, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Huang, Y.; Ho, S.H.; Lee, H.C. Insecticidal properties of eugenol, isoeugenol and methyleugenol and their effects on nutrition of Sitophilus zeamais. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2002, 38, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isman, M.B. Botanical insecticides in the twenty-first century—Fulfilling their promise? Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2020, 65, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özcan, M.M.; Chalchat, J.C. Chemical composition and antifungal effect of anise (Pimpinella anisum L.) fruit oil at ripening stage. Ann. Microbiol. 2006, 56, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitrescu, E.; Muselin, F.; Tîrziu, E.; Folescu, M.; Dumitrescu, C.S.; Orboi, D.M.; Cristina, R.T. Pimpinella anisum L. essential oil a valuable antibacterial and antifungal alternative. Plants 2023, 12, 2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elhafeez, E.M.A.; Ramadan, B.R.; Abou-El-Hawa, S.H.M.; Rashwan, M.R.A. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of anise and fennel essential oils. Assiut J. Agric. Sci. 2023, 54, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Shahrajabian, M.H.; Cheng, Q. Anise (Pimpinella anisum L.), a dominant spice and traditional medicinal herb for both food and medicinal purposes. Cogent Food Agric. 2019, 5, 1673688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noumi, E.; Ahmad, I.; Adnan, M.; Patel, H.; Merghni, A.; Haddaji, N.; Bouali, N.; Alabbosh, K.F.; Kadri, A.; Caputo, L.; et al. Illicium verum L. (star anise) essential oil: GC/MS profile, molecular docking study, in silico ADME profiling, quorum sensing, and biofilm-inhibiting effect on foodborne bacteria. Molecules 2023, 28, 7691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trongtokit, Y.; Rongsriyam, Y.; Komalamisra, N.; Apiwathnasorn, C. Comparative repellency of 38 essential oils against mosquito bites. Phytother. Res. 2005, 19, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nerio, L.S.; Olivero-Verbel, J.; Stashenko, E. Repellent activity of essential oils: A review. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 372–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkan, M.; Ertürk, S. Insecticidal Efficacy and Repellency of Trans-Anethole Against Four Stored-Product Insect Pests. J. Agric. Sci. 2020, 26, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Family | Common Name | Thai Name | Scientific Name | Part Used | Effecacy 1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concentrations (µL/L) | |||||||

| 10,000 | 1000 | 500 | |||||

| Apiaceae | Anise | Thein-Sat-Ta-Butr | Pimpinella anisum | Seeds | VH | H | - |

| Lauraceae | Cinnamon | Ob-Choei | Cinnamomum zeylanicum | Leaves | VH | VH | VH |

| Rutaceae | Kaffir lime | Ma-Krut | Citrus hystrix | Peel | VH | VL | - |

| Schisandraceae | Star anise | Chan-Paet-Klip | Illicium verum | Flower | VH | VH | M |

| Poaceae | Lemon grass | Ta-Khrai-Ban | Cymbopogon citratus | Stem and leaves | VH | L | - |

| Citronella grass | Ta-Khrai-Hom | Cymbopogon nardus | Stem and leaves | VH | L | - | |

| Lamiaceae | Peppermint | Sa-Ra-Nae | Mentha spp. | Leaves | VH | VL | - |

| Sweet basil | Ho-Ra-Pha | Ocimum basilicum | Leaves | VH | VL | - | |

| Myrtaceae | Cajeput tree | Sa-Met | Melaleuca leucadendron | Leaves | VH | VL | - |

| Clove | Kan-Phlu | Syzygium aromaticum | Buds | VH | VH | VH | |

| Blue gum | Eucalyptus | Eucalyptus camaldulensis | Leaves | VH | VL | - | |

| Zingiberaceae | Siam cardamom | Kra-Wan | Amomum krervanh | Roots | VH | VL | - |

| Phlai | Phlai | Zingiber cassumunar | Roots | VH | VL | - | |

| Turmeric | Khamin-Chan | Curcuma longa | Roots | H | VL | - | |

| Chemical Components | % | Formula | Molecular Weight (g/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clove essential oil | |||

| Eugenol | 66.69 | C10H12O2 | 164.20 |

| Caryophyllene | 17.34 | C15H24 | 204.35 |

| Humulene | 1.13 | C15H24 | 204.35 |

| α-Bisabolene | 6.22 | C15H24 | 204.35 |

| Cadinene | 2.74 | C15H24 | 204.35 |

| Neoclovene oxide | 1.20 | C15H24O | 220.35 |

| Betulenol | 1.39 | C30H50O2 | 442.72 |

| Other | 3.39 | ||

| Cinnamon essential oil | |||

| α-Pinene | 2.44 | C10H16 | 136.23 |

| Carene | 0.38 | C10H16 | 136.23 |

| p-Cymene | 2.26 | C10H14 | 134.22 |

| Linalool | 2.96 | C10H18O | 154.25 |

| Cinnamaldehyde | 1.75 | C9H8O | 132.16 |

| Safrole | 2.54 | C10H10O2 | 162.19 |

| Eugenol | 54.99 | C10H12O2 | 164.20 |

| Caryophyllene | 7.22 | C15H24 | 204.35 |

| Cinnamyl acetate | 3.88 | C11H12O2 | 176.21 |

| Humulene | 2.06 | C15H24 | 204.35 |

| Caryophyllene oxide | 2.00 | C15H24O | 220.35 |

| Benzyl Benzoate | 5.66 | C14H12O2 | 212.24 |

| Other | 11.86 | ||

| Star anise essential oil | |||

| Linalool | 1.39 | C10H18O | 154.25 |

| Anisic aldehyde | 1.81 | C8H8O2 | 136.15 |

| Anethole | 90.78 | C10H12O | 148.20 |

| α-Copaene | 0.81 | C15H24 | 204.35 |

| 1-(3-Methyl-2-butenoxy)-4-(1-propenyl)benzene | 1.23 | C14H18O | 202.29 |

| Other | 3.98 |

| Treatments/ After Treated (h) | % Mortality 1 (Means) | Regression Equation 2 | SE | χ2 | Toxicity Values 3 (µL/L) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concentrations (µL/L) | ||||||||||

| 0 | 100 | 250 | 500 | 750 | LC50 | LC90 | ||||

| Clove EO | ||||||||||

| 3 h | 0.0 d | 13.3 c | 66.7 b | 100.0 a | 100.0 a | Y = 0.011 − 2.358x | 0.229 | 1.606 | 208.6 | 322.0 |

| 6 h | 0.0 c | 30.0 b | 96.7 a | 100.0 a | 100.0 a | Y = 0.017 − 2.313x | 0.229 | 1.674 | 135.5 | 210.5 |

| 12 h | 0.0 c | 60.0 b | 100.0 a | 100.0 a | 100.0 a | Y = 0.039 − 3.630x | 2.240 | 0.017 | 93.6 | 126.7 |

| 18 h | 0.0 c | 70.0 b | 100.0 a | 100.0 a | 100.0 a | Y = 0.042 − 3.634x | 2.256 | 0.018 | 87.6 | 118.5 |

| 24 h | 0.0 b | 93.3 a | 100.0 a | 100.0 a | 100.0 a | Y = 0.050 − 3.561x | 1.996 | 0.023 | 70.6 | 96.0 |

| Cinnamon EO | ||||||||||

| 3 h | 0.0 c | 0.0 c | 20.0 b | 86.7 a | 100.0 a | Y = 0.009 − 3.109x | 0.263 | 2.323 | 362.6 | 512.1 |

| 6 h | 0.0 c | 0.0 c | 43.3 b | 100.0 a | 100.0 a | Y = 0.023 − 5.922x | 3.646 | 0.024 | 256.8 | 312.4 |

| 12 h | 0.0 c | 3.3 c | 60.0 b | 100.0 a | 100.0 a | Y = 0.014 − 3.272x | 0.393 | 0.070 | 231.8 | 322.6 |

| 18 h | 0.0 d | 13.3 c | 76.7 b | 100.0 a | 100.0 a | Y = 0.013 − 2.486x | 0.243 | 0.934 | 191.9 | 290.8 |

| 24 h | 0.0 c | 20.0 b | 100.0 a | 100.0 a | 100.0 a | Y = 0.028 − 3.700x | 0.960 | 0.073 | 130.5 | 175.7 |

| Star anise EO | ||||||||||

| 3 h | 0.0 c | 0.0 c | 0.0 c | 46.7 b | 100.0 a | Y = 0.014 − 7.039x | 2.398 | 0.069 | 507.0 | 599.3 |

| 6 h | 0.0 d | 6.3 cd | 13.3 c | 50.0 b | 100.0 a | Y = 0.006 − 2.498x | 0.182 | 16.055 | 450.3 | 681.3 |

| 12 h | 0.0 d | 6.7 d | 23.3 c | 60.0 b | 100.0 a | Y = 0.005 − 2.226x | 0.162 | 10.403 | 408.1 | 643.1 |

| 18 h | 0.0 d | 13.3 d | 36.7 c | 63.3 b | 100.0 a | Y = 0.005 − 1.779x | 0.134 | 17.995 | 365.4 | 628.7 |

| 24 h | 0.0 e | 16.7 d | 43.3 c | 70.0 b | 100.0 a | Y = 0.005 − 1.635x | 0.128 | 18.050 | 332.8 | 593.7 |

| Eugenol standard | ||||||||||

| 3 h | 0.0 c | 0.0 c | 20.0 b | 100.0 a | 100.0 a | Y = 0.019 − 5.524x | 2.481 | 0.019 | 294.9 | 362.9 |

| 6 h | 0.0 c | 0.0 c | 46.7 b | 100.0 a | 100.0 a | Y = 0.023 − 5.799x | 3.039 | 0.047 | 252.8 | 308.6 |

| 12 h | 0.0 d | 13.3 c | 70.0 b | 100.0 a | 100.0 a | Y = 0.012 − 2.394x | 0.234 | 1.347 | 202.9 | 311.6 |

| 18 h | 0.0 d | 20.0 c | 86.7 b | 100.0 a | 100.0 a | Y = 0.014 − 2.329x | 0.221 | 1.517 | 167.0 | 258.9 |

| 24 h | 0.0 c | 43.3 b | 100.0 a | 100.0 a | 100.0 a | Y = 0.032 − 3.338x | 1.392 | 0.082 | 104.5 | 144.6 |

| Anethole standard | ||||||||||

| 3 h | 0.0 d | 0.0 d | 16.7 c | 66.7 b | 100.0 a | Y = 0.007 − 2.932x | 0.239 | 5.873 | 418.8 | 601.8 |

| 6 h | 0.0 c | 0.0 c | 26.7 b | 100.0 a | 100.0 a | Y = 0.020 − 5.520x | 3.039 | 0.024 | 281.2 | 346.5 |

| 12 h | 0.0 d | 16.7 c | 36.7 b | 100.0 a | 100.0 a | Y = 0.008 − 2.251x | 0.179 | 25.814 | 276.9 | 434.5 |

| 18 h | 0.0 d | 26.7 c | 43.3 b | 100.0 a | 100.0 a | Y = 0.008 − 1.813x | 0.154 | 21.926 | 234.3 | 399.8 |

| 24 h | 0.0 d | 36.7 c | 53.3 b | 100.0 a | 100.0 a | Y = 0.008 − 1.796x | 0.160 | 14.359 | 216.6 | 371.1 |

| Treatments/ Concentrations (µL/L or mg/L) | % Mortality 1 (Means) | Regression Equation 2 | SE | χ2 | Toxicity Values 3 (h) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| After Various Exposure Times (h) | LT50 | LT90 | |||||||||

| 3 | 6 | 12 | 18 | 24 | |||||||

| Clove EO | |||||||||||

| 100 | 13.3 d | 30.0 cd | 60.0 bc | 70.0 ab | 93.3 a | Y = 0.012 − 1.274x | 0.126 | 6.621 | 11.42 | 22.91 | |

| 250 | 66.7 b | 96.7 a | 100.0 a | 100.0 a | 100.0 a | Y = 0.469 − 0.975x | 0.355 | <0.001 | 2.08 | 4.81 | |

| Cinnamon EO | |||||||||||

| 100 | 0.0 c | 0.0 c | 3.3 bc | 13.3 ab | 20.0 a | Y = 0.096 − 3.038x | 0.333 | 3.259 | 31.65 | 45.00 | |

| 250 | 20.0 d | 43.3 c | 60.0 bc | 76.7 b | 100.0 a | Y = 0.116 − 1.083x | 0.124 | 12.877 | 9.31 | 20.32 | |

| Star anise EO | |||||||||||

| 100 | 0.0 | 6.3 | 6.7 | 13.3 | 16.7 | Y = 0.050 − 2.097x | 0.200 | 5.21 | 41.91 | 67.51 | |

| 250 | 0.0 | 13.3 | 23.3 | 36.7 | 43.3 | Y = 0.072 − 1.750x | 0.152 | 11.983 | 24.283 | 42.062 | |

| Eugenol standard | |||||||||||

| 100 | 0.0 c | 0.0 c | 13.3 b | 20.0 b | 43.3 a | Y = 0.109 − 2.752x | 0.245 | 7.752 | 25.19 | 36.92 | |

| 250 | 20.0 e | 46.7 d | 70.0 c | 86.7 b | 100.0 a | Y = 0.134 − 1.083x | 0.128 | 7.429 | 8.07 | 17.63 | |

| Anethole standard | |||||||||||

| 100 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 16.7 | 26.7 | 36.7 | Y = 0.092 − 2.441x | 0.213 | 13.143 | 25.91 | 39.52 | |

| 250 | 16.7 | 26.7 | 36.7 | 43.3 | 53.3 | Y = 0.045 − 0.968x | 0.119 | 1.638 | 21.41 | 49.76 | |

| Insecticides (Recommended dose) | |||||||||||

| Fipronil | 250 | 43.3 b | 90.0 a | 100.0 a | 100.0 a | 100.0 a | Y = 0.484 − 1.620x | 0.304 | 0.001 | 3.35 | 6.00 |

| Cypermethrin | 2000 | 100.0 a | 100.0 a | 100.0 a | 100.0 a | 100.0 a | - | - | - | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chantarapitak, C.; Pumnuan, J.; Chanpitak, C.; Kramchote, S. In Vitro Termiticidal Activity of Medicinal Plant Essential Oils Against Microcerotermes crassus. Insects 2025, 16, 1261. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16121261

Chantarapitak C, Pumnuan J, Chanpitak C, Kramchote S. In Vitro Termiticidal Activity of Medicinal Plant Essential Oils Against Microcerotermes crassus. Insects. 2025; 16(12):1261. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16121261

Chicago/Turabian StyleChantarapitak, Chaiamon, Jarongsak Pumnuan, Chaiwat Chanpitak, and Somsak Kramchote. 2025. "In Vitro Termiticidal Activity of Medicinal Plant Essential Oils Against Microcerotermes crassus" Insects 16, no. 12: 1261. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16121261

APA StyleChantarapitak, C., Pumnuan, J., Chanpitak, C., & Kramchote, S. (2025). In Vitro Termiticidal Activity of Medicinal Plant Essential Oils Against Microcerotermes crassus. Insects, 16(12), 1261. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16121261