Diversity and Functional Analysis of Gut Microbiota in the Adult of Lissorhoptrus oryzophilus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) by Metagenome Sequencing

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

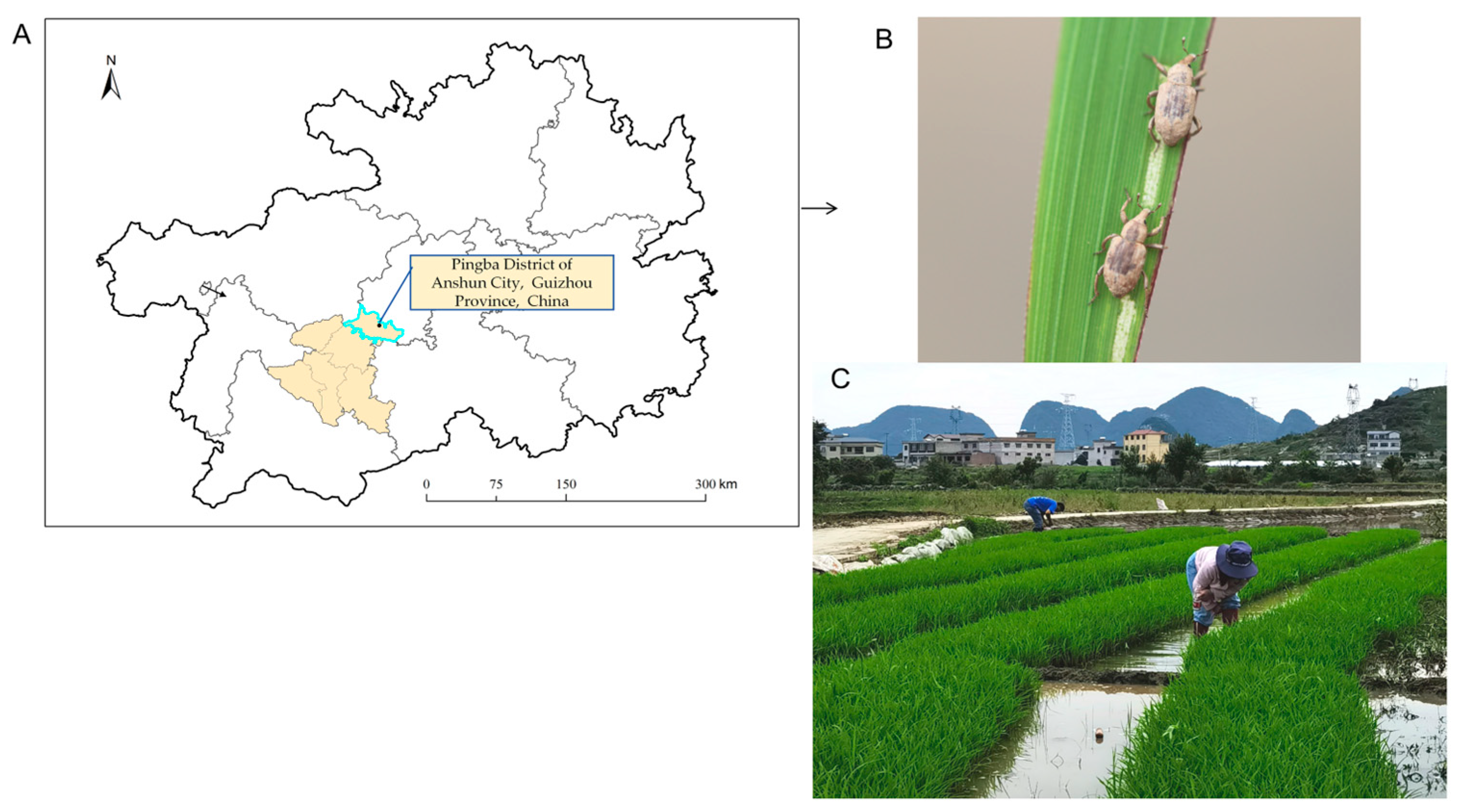

2.1. Species Collection

2.2. Gut Dissection

2.3. DNA Extraction of Gut Microbiota

2.4. Metagenome Sequencing and Bioinformatic Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Midgut DNA Extraction and Quality Assessment from L. oryzophilus

3.2. Quality Control of Gut Microbiota DNA Sequencing Data from L. oryzophilus

3.3. Metagenome Assembly of Gut Microbiota from L. oryzophilus

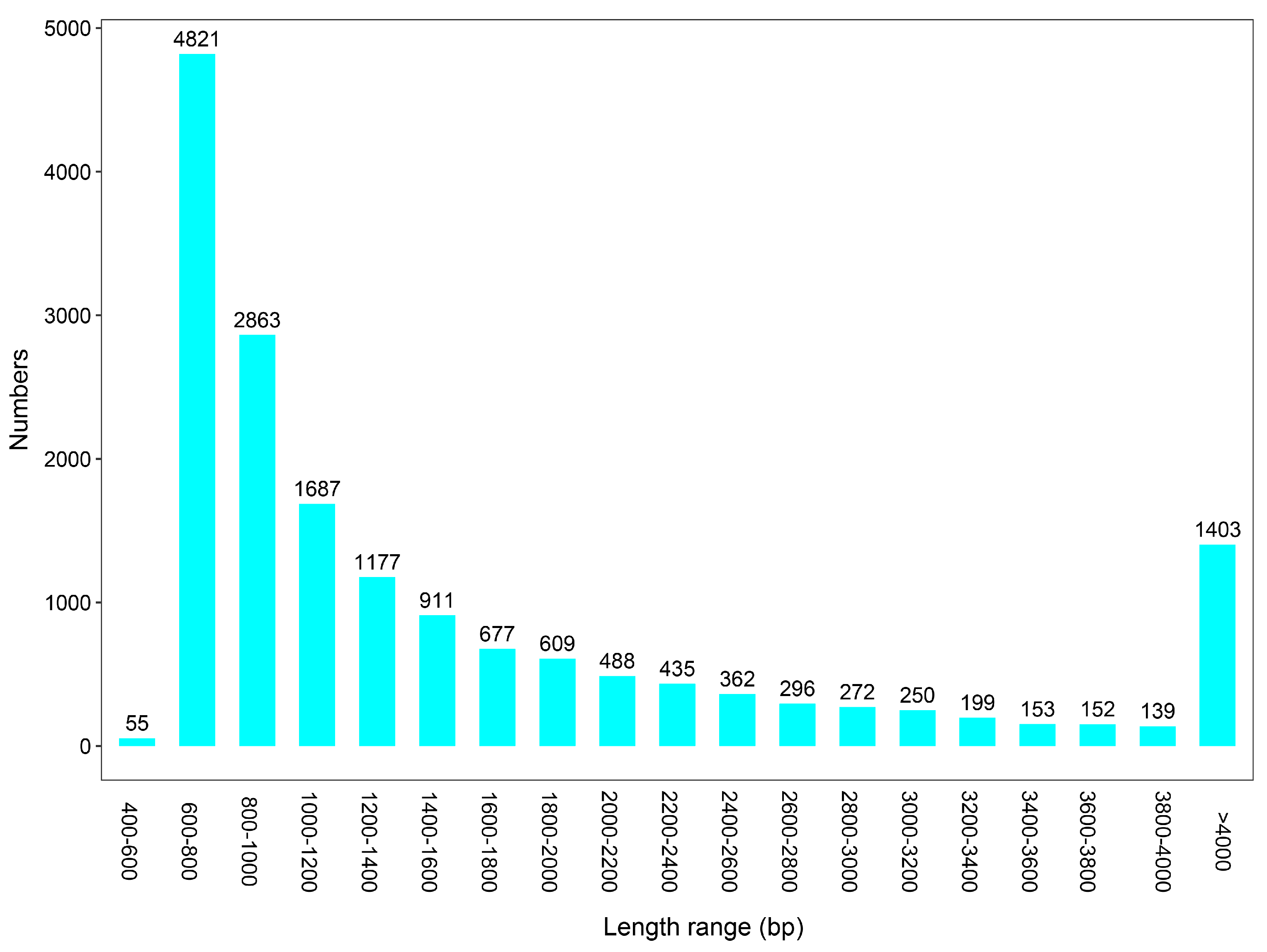

3.4. Composition Analysis of Gut Microbiota Metagenome in L. oryzophilus

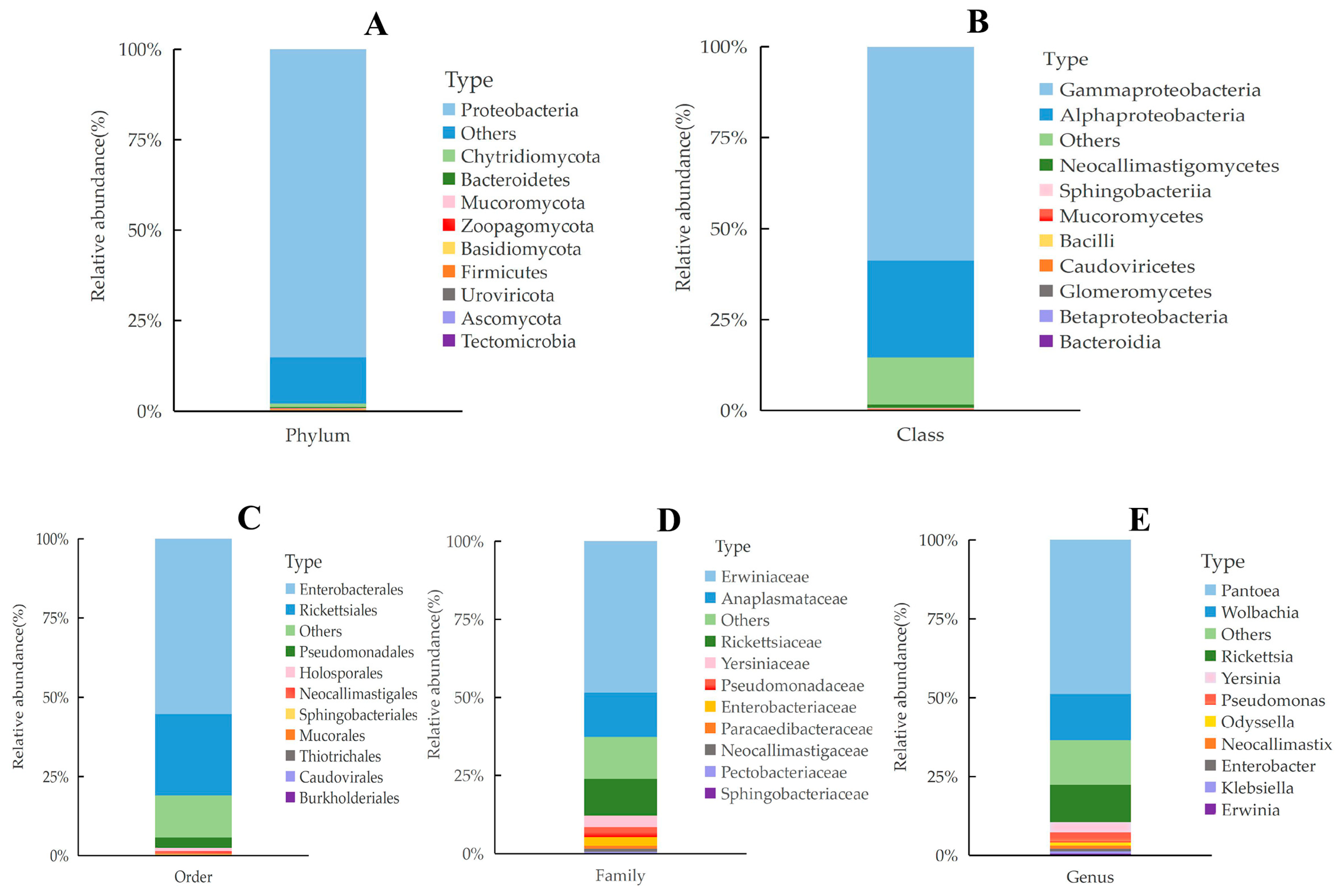

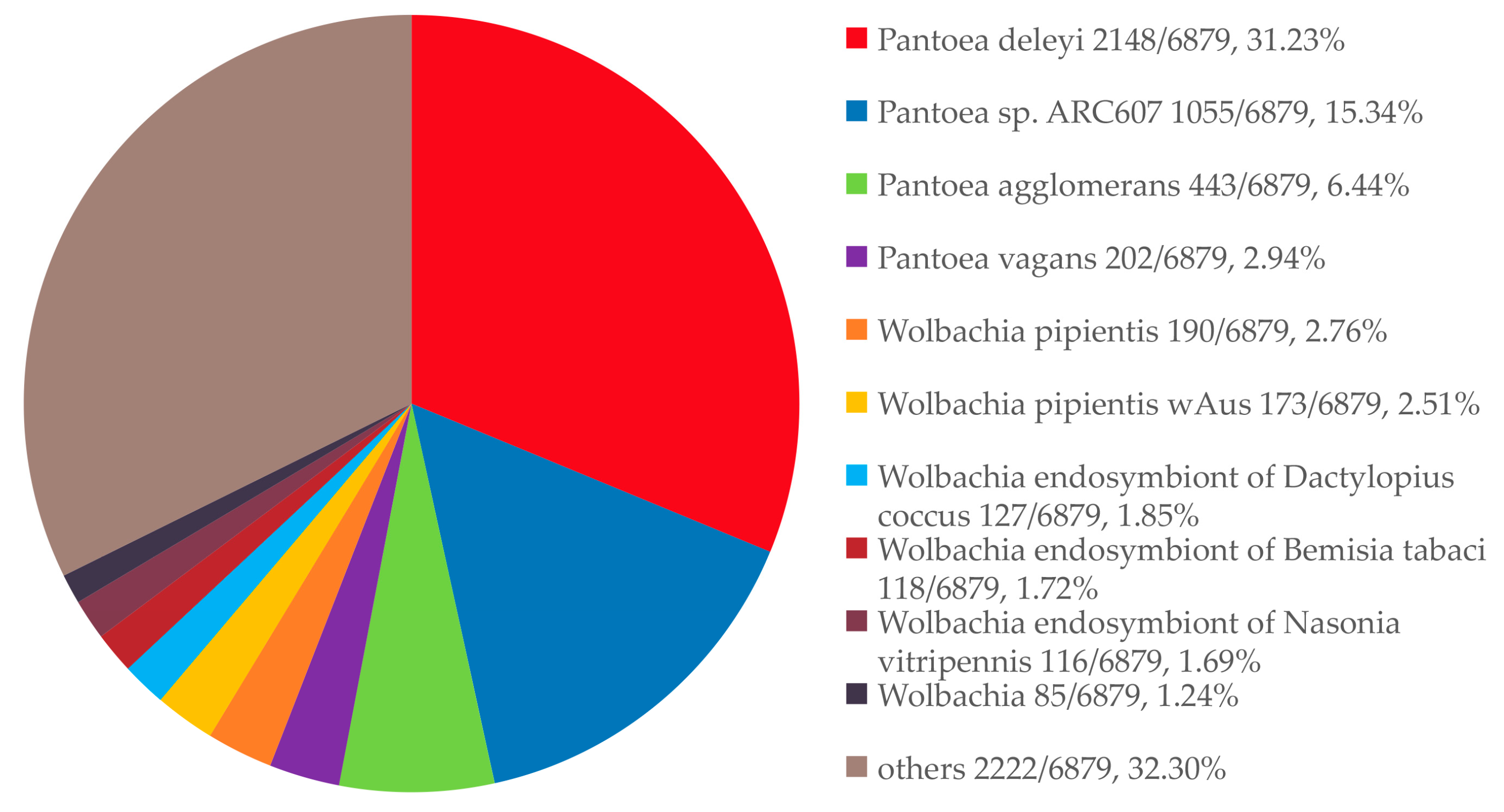

3.5. Taxonomic Composition and Relative Abundance of Gut Microbiota in L. oryzophilus

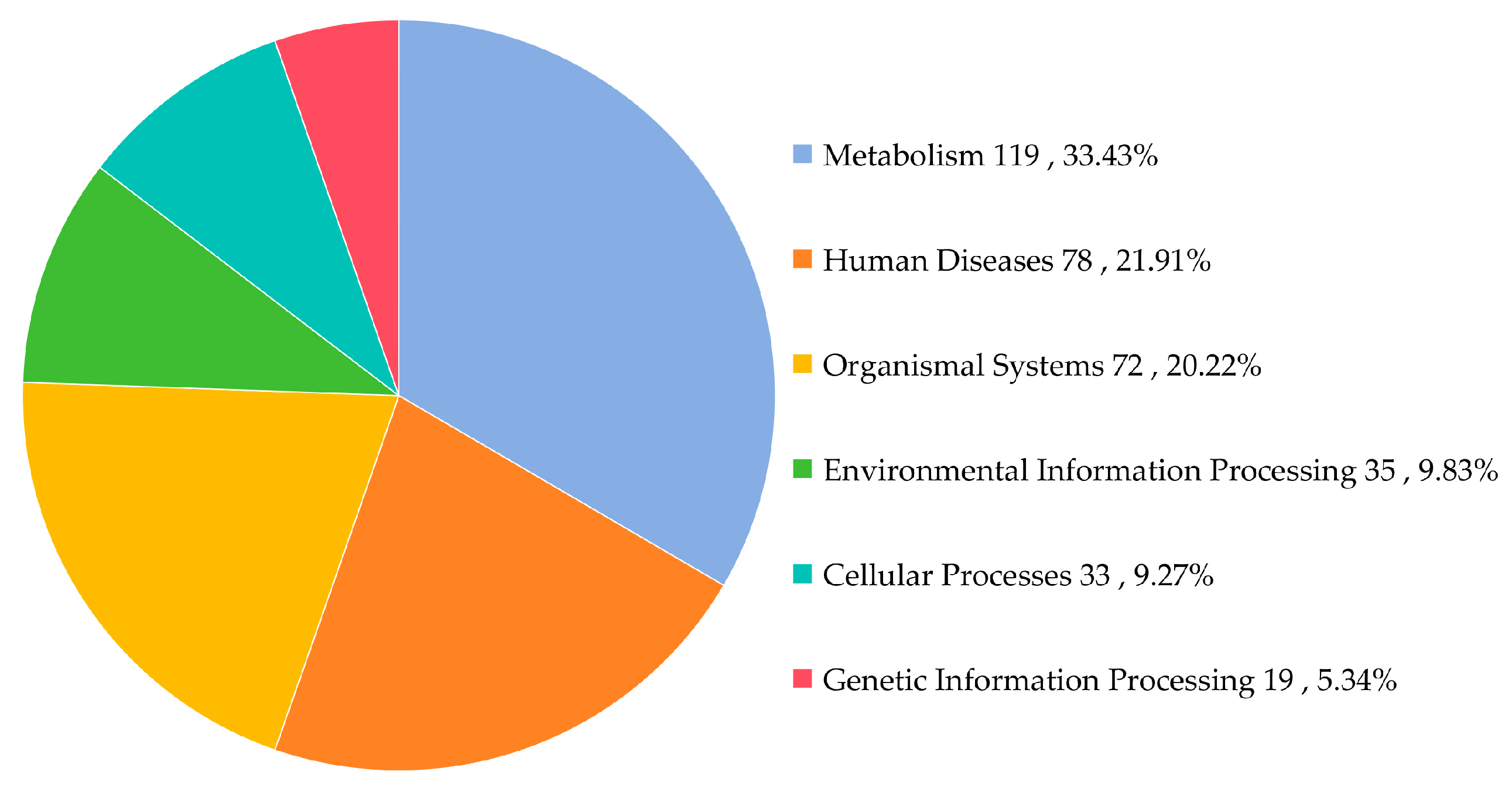

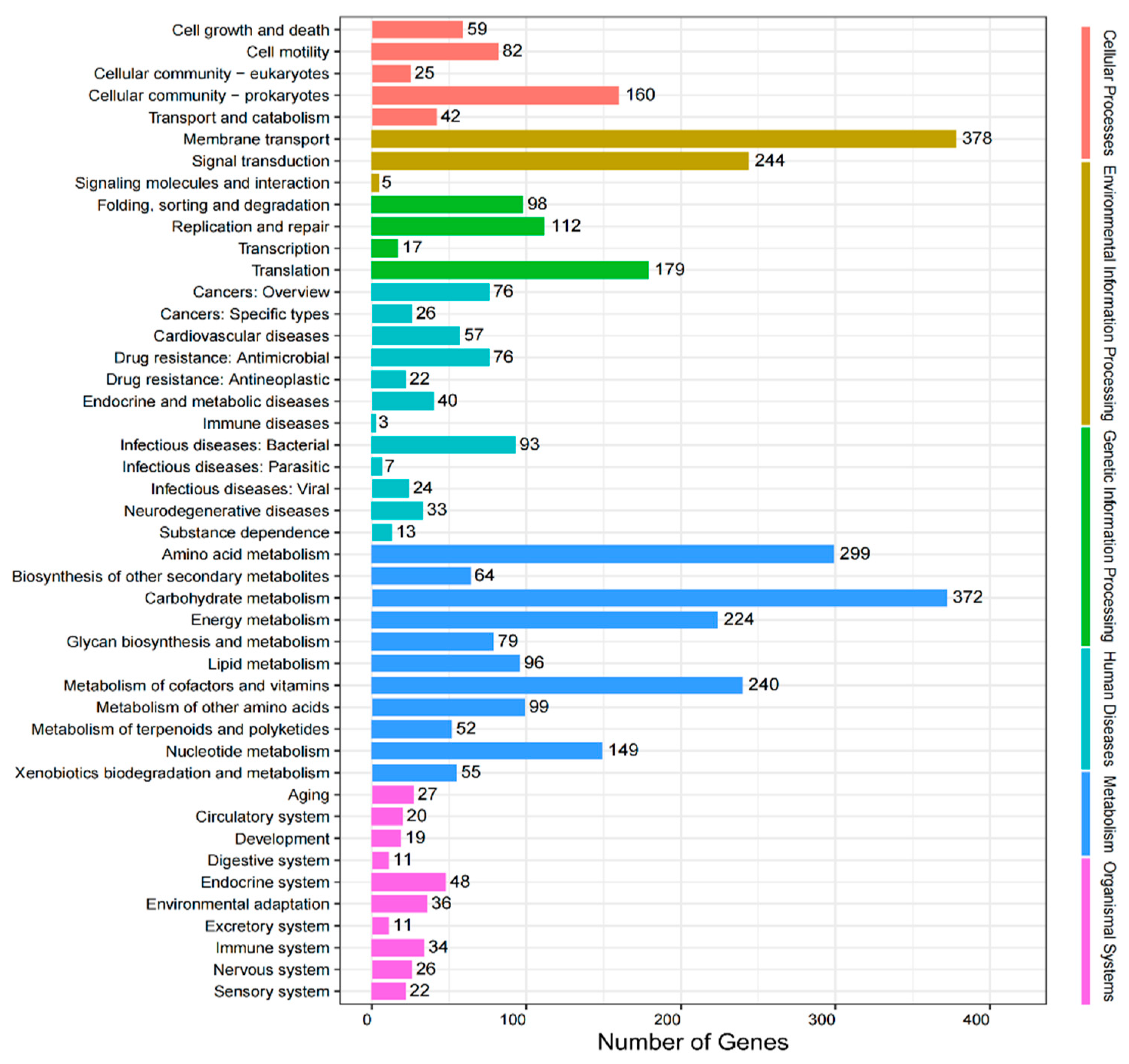

3.6. KEGG Pathway Analysis of Gut Microbiota in L. oryzophilus

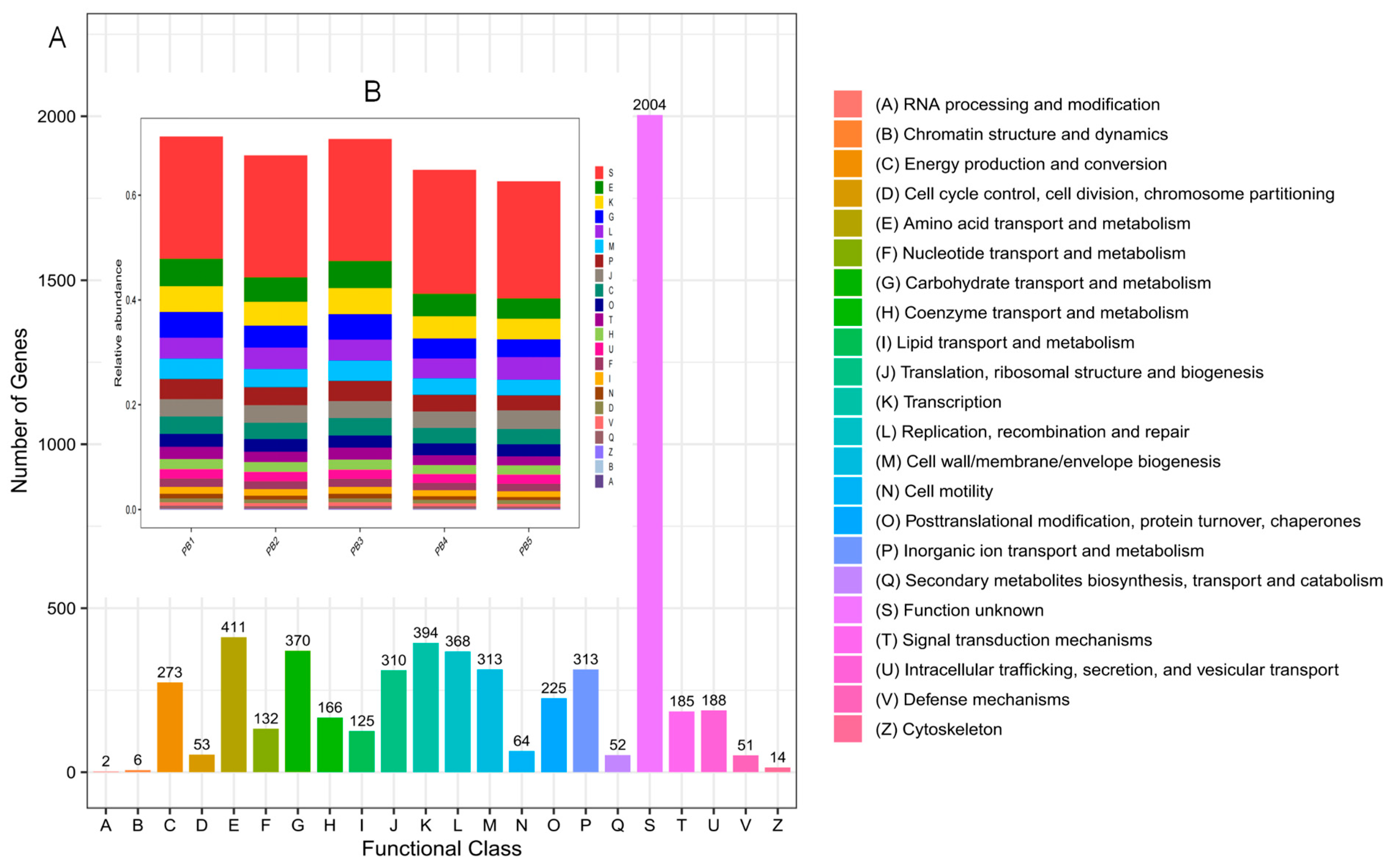

3.7. Functional Annotation Based on the eggNOG Database

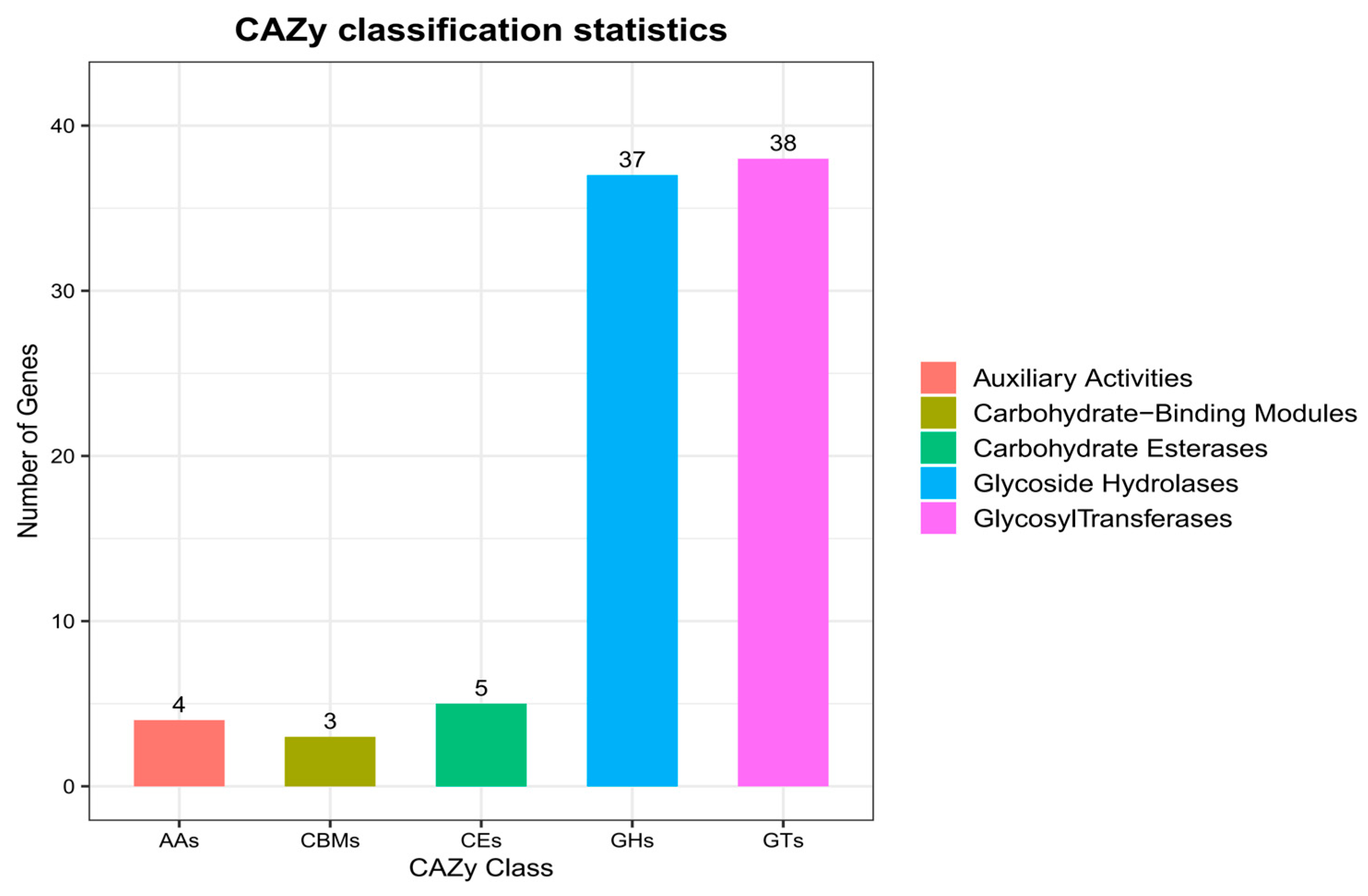

3.8. Functional Annotation Based on the Carbohydrate-Active Enzymes (CAZy) Database

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| Nr | Non-Redundant Protein Database |

| eggNOG | Evolutionary Genealogy of Genes: Non-supervised Orthologous Groups |

| CAZy | Carbohydrate-Active enZymes |

| GHs | Glycoside hydrolases |

| GTs | Glycosyl transferases |

| PLs | Polysaccharide lyases |

| CEs | Carbohydrate esterases |

| AAs | Auxiliary activities |

| CBMs | Carbohydrate-binding modules |

References

- Kuschel, G. Revision of Lissorhoptrus of Contey generos vecinos in America. Rev. Chil. Entomol. 1951, 1, 23–74. [Google Scholar]

- Heinrichs, E.A.; Quisenberry, S.S. Germplasm evaluation and utilization for insect resistance in rice. In Global Plant Genetic Resources for Insect-Resistance Crops; Clement, S.L., Quisenberry, S.S., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1999; pp. 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China. Announcement of the Former State Environmental Protection Administration: The Second Batch of Invasive Alien Species in China (Huan Fa [2010] No. 4). 2010. Available online: https://www.mee.gov.cn/gkml/hbb/bwj/201001/t20100126_184831.htm (accessed on 7 January 2010).

- Announcement No. 1897 of the Ministry of Agriculture of the People’s Republic of China. J. Biosaf. 2013, 22, 215–216. [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. Announcement No. 567: Catalogue of Key Managed Invasive Alien Species. 2022. Available online: http://www.moa.gov.cn/govpublic/KJJYS/202211/t20221109_6415160.htm (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- Heinrichs, E.A. Host plant resistance. In Biology and Management of Rice Insects; Heinrichs, E.A., Ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1994; pp. 517–547. ISBN 978-04-702-1814-3. [Google Scholar]

- Saito, T.; Hirai, K.; Way, M.O. The rice water weevil, Lissorhoptrus oryzophilus Kusehel (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Appl. Entomol. Zool. 2005, 40, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Way, M.O. Insect pest management in rice in the United States. In Pest Management in Rice; Grayson, B.T., Green, M.B., Copping, L.G., Eds.; Elsevier Applied Science Publishers: Barking, UK, 1990; pp. 181–189. ISBN 978-94-009-0775-1. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, L.I.; Stout, M.J.; Dundand, R.T. The effects of feeding by the rice water weevil, Lissorhoptrus oryzophilus Kushel, on the growth and yield components of rice, Oryza sativa. Agric. For. Entomol. 2004, 6, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reay-Jones, F.P.F.; Way, M.O.; Tarpley, L. Nitrogen fertilization at the rice panicle differentiation stage to compensate for rice water weevil (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) injury. Crop. Prot. 2008, 27, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.L.; Reitz, S.R. Emerging themes in our understanding of species displacements. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2017, 62, 165–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macke, E.; Tasiemski, A.; Massol, F.; Callens, M.; Decaestecker, E. Life history and eco-evolutionary dynamics in light of the gut microbiota. Oikos 2017, 126, 508–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Lin, J.; Lin, Z.; Li, Q.R.; Huang, J.Y.; Wu, Q.J.; Ji, Q.H. Functions and applications of intestinal symbiotic microorganisms in insects. Asian Agric. Res. 2024, 16, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Fang, Y.; Zhou, Z.B.; He, Y.Q.; Zhang, Y. Research progress on pathogens carried by sand flies and their gut microbiota. Chin. J. Parasitol. Parasit. Dis. 2025, 43, 129–139. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, L.V.; Bry, L.; Falk, P.G.; Gordon, J.I. Hosts-microbial symbiosis in the mammalian intestine: Exploring an internal ecosystem. BioEssays 1998, 20, 336–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omondi, Z.N.; Arserim, S.K.; Töz, S.; Özbel, Y. Host-parasite interactions: Regulation of Leishmania infection in sand fly. Acta Parasitol. 2022, 67, 606–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.L.; Lyu, B.Q.; Yang, F.; Tu, Y.; Jiang, F.Y.D.; Qi, K.X.; Li, Z.C. Isolation, identification and functional analysis of intestinal microorganisms of Brontispa longissimi Gestro. Chin. J. Tropic. Crops 2021, 42, 1066–1070. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.T.; Lan, B.M.; Wang, Q.; Xia, X.F.; You, M.S. Isolation and Preliminary functional analysis of the larval gut bacteria from Spodoptera litura larvae. Biot. Resour. 2017, 39, 264–271. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.J.; Lu, F.; Jiang, M.X.; Way, M.O. Identification and biological role of the endosymbionts Wolbachia in rice water weevil (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Environ. Entomol. 2012, 41, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, F.; Kang, X.; Jiang, C.; Lou, B.G.; Jiang, M.X.; Way, M.O. Isolation and characterization of bacteria from midgut of the rice water weevil (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Environ. Entomol. 2013, 42, 874–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, F.; Kang, X.; Lorenz, G.; Espino, L.; Jiang, M.X.; Way, M.O. Culture-independent analysis of bacterial communities in the gut of rice water weevil (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 2014, 107, 592–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, A.E. Multiorganismal insects: Diversity and function of resident microorganisms. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2015, 60, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Li, H. Research progress in the application of metagenomics in animal gut microbes. Anhui Agric. Sci. 2022, 50, 18–20+29. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suau, A.; Bonnet, R.; Sutren, M.; Godon, J.J.; Gibson, G.R.; Collins, M.D.; Doré, J. Direct analysis of genes encoding 16S rRNA from complex communities reveals many novel molecular species within the human gut. Appl. Environ. Microb. 1999, 65, 4799–4807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furrie, E. A molecular revolution in the study of intestinal microflora. Gut 2006, 55, 141–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Ning, K. Metagenomics of insect gut: New borders of microbial big data. Acta Microbiol. Sin. 2018, 58, 964–984. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, P.; Moran, N.A. The gut microbiota of insects-diversity in structure and function. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2013, 37, 699–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, C.N.; Trautman, E.P.; Crawford, J.M.; Stabb, E.V.; Handelsman, J.O.; Broderick, N.A. Metabolite exchange between microbiome members produces compounds that influence Drosophila behavior. Elife 2017, 6, e18855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, F.; Pang, Z.C.; Yu, X.Q.; Wang, X.Y. Insect gut microbiota research: Progress and applications. Chin. J. Appl. Entomol. 2020, 57, 600–607. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.X.; Liu, Y.Q.; Li, Q.; Xia, R.X.; Wang, H. Research progress on intestinal microbial diversity of insects. J. Henan Agric. Sci. 2016, 45, 1–7. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D.F.; Li, H.J.; Lu, Y.Y. Research progress of the influence of microorganisms on insect behavior. Acta Entomol. Sin. 2021, 64, 743–756. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji-Hyun, Y.; Woon, S.R.; Woong, T.W.; Jung, M.J.; Kim, M.S.; Park, D.S.; Yoon, C.M.; Nam, Y.D.; Kim, Y.J.; Choi, J.H.; et al. Insect gut bacterial diversity determined by environmental habitat, diet, developmental stage, and phylogeny of host. Appl. Environ. Microb. 2014, 80, 5254–5264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.J.; Li, H.W.; Li, X.Y.; Shen, A.D.; Yu, Y.X. Diversity analysis of gut microbes of yellow spined bamboo locust Ceracris kiangsu Tsai. J. Environ. Entomol. 2023, 45, 952–964. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.W.; Zhang, H.Y. The impact of environmental heterogeneity and life stage on the hindgut microbiota of Holotrichia parallela larvae (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae). PLoS ONE 2017, 8, e57169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.X.; Guo, Q.Y.; Wang, X.X.; Duffy, K.J.; Dai, X.H. Midgut bacterial diversity of a leaf-mining beetle, Dactylispa xanthospila (Gestro) (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae: Cassidinae). Biodivers. Data J. 2021, 9, e62843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.Z.; Wang, Z.L.; Zhu, H.F.; Wang, Z.Y.; Yu, X.P. Analysis of the gut microbial diversity of the brown planthopper, Nilaparvata lugens (Hemiptera: Delphacidae) by high-throughput sequencing. Acta Entomol. Sin. 2019, 62, 323–333. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schloss, D.P.; Delalibera, I.; Handelsman, J.; Raffa, K.F. Bacteria associated with the guts of two wood-boring beetles: Anoplophora glabripennis and Saperda vestita (Cerambycidae). Environ. Entomol. 2006, 35, 625–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.L.; Nan, X.N.; Ren, Z.Z.; Ming, J.; Tang, G.H. Diversity of intestinal bacteria communities from Atrijuglans hetaohei (Lepidoptera: Heliodinidae) and Dichocrocis punctiferalis (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) larvae estimated by PCR-DGGE and T-RFLP analysis. Sci. Silvae Sin. 2016, 52, 76–85. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.Y.; Sun, B.; Wu, H.L.; Hu, X.M.; Hao, Y.; Ye, J.M. Research progress on function of insect’s gut microbiota and the microbial of Bombyx mori. N. Seric. 2015, 36, 1–4+33. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.H.; Zhou, Y.; Xia, X.H.; Zhao, X.Y.; Qiao, H.; Tan, J.J.; Hao, D.J. Diversity and function of intestinal bacteria in adult Monochamus alternatus Hope (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) fed indoors and outdoors. Acta Microbiol. Sin. 2021, 61, 683–694. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, S.P.; Beran, F. Gut microbiota degrades toxic isothiocyanates in a flea beetle pest. Mol. Ecol. 2020, 29, 4692–4705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.H.; Wu, W.J.; Fu, Y.G. Bacterial community in Aleurodicus dispersus (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) estimated by PCR-DGGE and 16S rRNA gene library analysis. Acta Entomol. Sin. 2012, 55, 772–781. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, S.M.; Raven, R.J.; McGraw, E.M. Wolbachia pipientis in Australian spiders. Curr. Microbiol. 2004, 49, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartelt, K.; Oehme, R.; Frank, H.; Brockmann, S.O.; Hassler, D.; Kimmig, P. Pathogens and symbionts in ticks: Prevalence of Anaplasma phagocytophilum (Ehrlichia sp.), Wolbachia sp., Rickettsia sp., and Babesia sp. in southern Germany. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2004, 293, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiggins, F.M. The rate of recombination in Wolbachia bacteria. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2002, 19, 1640–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ros, V.I.D.; Breeuwer, J.A.J.; Menken, S.B.J. Origins of asexuality in Bryobia mites (Acari: Tetranychidae). BMC Evol. Biol. 2008, 31, 8–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilgenboecker, K.; Hammerstein, P.; Schlattmann, P.; Telschow, A.; Werren, J.H. How many species are infected with Wolbachia?—A statistical analysis of current data. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2008, 281, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werren, J.H.; Baldo, L.; Clark, M.E. Wolbachia: Master manipulators of invertebrate biology. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2008, 6, 741–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Hernández, M.G.; Rincón-Rosales, R.; Rincón-Molina, C.I.; Manzano-Gómez, L.A.; Gen-Jiménez, A.; Maldonado-Gómez, J.C.; Rincón-Molina, F.A. Diversity and functional potential of gut bacteria associated with the insect Arsenura armida (Lepidoptera: Saturniidae). Insects 2025, 16, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suen, G.; Scott, J.J.; Aylward, F.O.; Adams, S.M.; Tringe, S.G.; Pinto-Tomás, A.A.; Foster, C.E.; Pauly, M.; Weimer, P.J.; Barry, K.W.; et al. An insect herbivore microbiome with high plant biomass-degrading capacity. PLoS Genet. 2010, 6, e1001129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.T.; Sanchez, L.G.; Fierer, N. A cross-taxon analysis of insect-associated bacterial diversity. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Serial Number | Sample Name | Qubit Concentration (ng/μL) | Total Amount (μg) | OD260/280 | OD260/230 | Sample Grade * | Test Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PB1 | 152.0 | 5.32 | 2.062 | 2.384 | A | eligible |

| 2 | PB2 | 148.1 | 5.19 | 2.068 | 2.356 | A | eligible |

| 3 | PB3 | 148.9 | 5.21 | 2.062 | 2.416 | A | eligible |

| 4 | PB4 | 119.9 | 4.2 | 2.007 | 2.436 | A | eligible |

| 5 | PB5 | 147.3 | 5.16 | 2.007 | 2.365 | A | eligible |

| Sample | Raw Reads | Raw Bases | Trimmed Reads | Trimmed Bases | Trimmed_Q20 | Trimmed_Q30 | Trimmed_GC | Effective |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PB1 | 765,994 | 114,899,100 | 764,622 | 112,788,700 | 99.72% | 98.79% | 47.00% | 98.16% |

| PB2 | 675,668 | 101,350,200 | 673,830 | 97,153,533 | 99.44% | 98.17% | 45.77% | 95.86% |

| PB3 | 792,488 | 118,873,200 | 790,040 | 114,780,156 | 99.40% | 98.03% | 47.08% | 96.56% |

| PB4 | 590,862 | 88,629,300 | 588,910 | 85,678,697 | 99.43% | 98.12% | 44.10% | 96.67% |

| PB5 | 603,798 | 90,569,700 | 601,938 | 88,026,543 | 99.39% | 98.00% | 43.14% | 97.19% |

| Sample | Number | Total Len (bp) | Average Len (bp) | Max Len (bp) | Min Len (bp) | N50 | L50 | N90 | L90 | GC (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PB1 | 3141 | 4,999,651 | 1591.74 | 13,320 | 600 | 2024 | 732 | 753 | 2394 | 53.75 |

| PB2 | 3079 | 6,522,469 | 2118.37 | 19,046 | 502 | 3401 | 543 | 832 | 2151 | 49.68 |

| PB3 | 2900 | 7,109,211 | 2451.45 | 70,421 | 507 | 5740 | 268 | 818 | 1888 | 49.13 |

| PB4 | 4036 | 6,301,918 | 1561.43 | 14,834 | 545 | 1931 | 939 | 756 | 3108 | 48.61 |

| PB5 | 3793 | 6,012,806 | 1585.24 | 27,067 | 515 | 1948 | 836 | 761 | 2908 | 48.07 |

| Sample | Number | Integrity: Start | Integrity: End | Integrity: All | Integrity: None | Total Len (bp) | Average Len (bp) | Max Len (bp) | Min Len (bp) | N50 | L50 | GC (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PB1 | 6493 | 1241 (19.11%) | 1970 (30.34%) | 3056 (47.07%) | 226 (3.48%) | 3,919,968 | 603.72 | 3807 | 102 | 831 | 1599 | 55.85 |

| PB2 | 7246 | 1000 (13.80%) | 1657 (22.87%) | 4440 (61.28%) | 149 (2.06%) | 4,924,452 | 679.61 | 6732 | 102 | 939 | 1741 | 52.61 |

| PB3 | 7189 | 766 (10.66%) | 1279 (17.79%) | 5043 (70.15%) | 101 (1.40%) | 5,225,364 | 726.86 | 17,046 | 102 | 1011 | 1707 | 52.94 |

| PB4 | 7405 | 1275 (17.22%) | 2215 (29.91%) | 3708 (50.07%) | 207 (2.80%) | 4,449,258 | 600.85 | 4905 | 102 | 831 | 1796 | 52.40 |

| PB5 | 7282 | 1238 (17.00%) | 2156 (29.61%) | 3681 (50.55%) | 207 (2.84%) | 4,372,515 | 600.46 | 5271 | 102 | 834 | 1733 | 51.07 |

| Kingdom | Phylum | Class | Order | Family | Genus | Species |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | Proteobacteria | Gammaproteobacteria | Enterobacterales | Erwiniaceae | Pantoea | Pantoea deleyi |

| Pantoea sp. ARC607 | ||||||

| Pantoea agglomerans | ||||||

| Pantoea vagans | ||||||

| Alphaproteobacteria | Rickettsiales | Anaplasmataceae | Wolbachia | Wolbachia pipientis | ||

| Wolbachia pipientis wAus | ||||||

| Wolbachia endosymbiont of Dactylopius coccus | ||||||

| Wolbachia endosymbiont of Bemisia tabaci | ||||||

| Wolbachia endosymbiont of Nasonia vitripennis | ||||||

| Wolbachia |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jin, J.-X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, G.-F.; Ye, Z.-C.; Liu, B.; Yao, D.-D.; Jiang, Z.-C.; He, Y.-F. Diversity and Functional Analysis of Gut Microbiota in the Adult of Lissorhoptrus oryzophilus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) by Metagenome Sequencing. Insects 2025, 16, 1260. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16121260

Jin J-X, Wang Y, Zhang G-F, Ye Z-C, Liu B, Yao D-D, Jiang Z-C, He Y-F. Diversity and Functional Analysis of Gut Microbiota in the Adult of Lissorhoptrus oryzophilus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) by Metagenome Sequencing. Insects. 2025; 16(12):1260. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16121260

Chicago/Turabian StyleJin, Jian-Xue, Yu Wang, Gui-Fen Zhang, Zhao-Chun Ye, Bo Liu, Dan-Dan Yao, Zhao-Chun Jiang, and Yong-Fu He. 2025. "Diversity and Functional Analysis of Gut Microbiota in the Adult of Lissorhoptrus oryzophilus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) by Metagenome Sequencing" Insects 16, no. 12: 1260. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16121260

APA StyleJin, J.-X., Wang, Y., Zhang, G.-F., Ye, Z.-C., Liu, B., Yao, D.-D., Jiang, Z.-C., & He, Y.-F. (2025). Diversity and Functional Analysis of Gut Microbiota in the Adult of Lissorhoptrus oryzophilus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) by Metagenome Sequencing. Insects, 16(12), 1260. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16121260