Knockdown of Serine–Arginine Protein Kinase 3 Impairs Sperm Development in Spodoptera frugiperda

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Insect Rearing and Maintenance

2.2. Detection of Sperm Bundles by Fluorescence in Situ Hybridization (FISH)

2.3. dsRNA Synthesis for RNAi

2.4. dsRNA Microinjection Through Hemolymph

2.5. Detection of Sperm Morphological Changes After SRPK3 Knockdown

2.6. Quantitative Real-Time PCR for Gene Expression Analysis

2.7. Data Analysis

3. Results

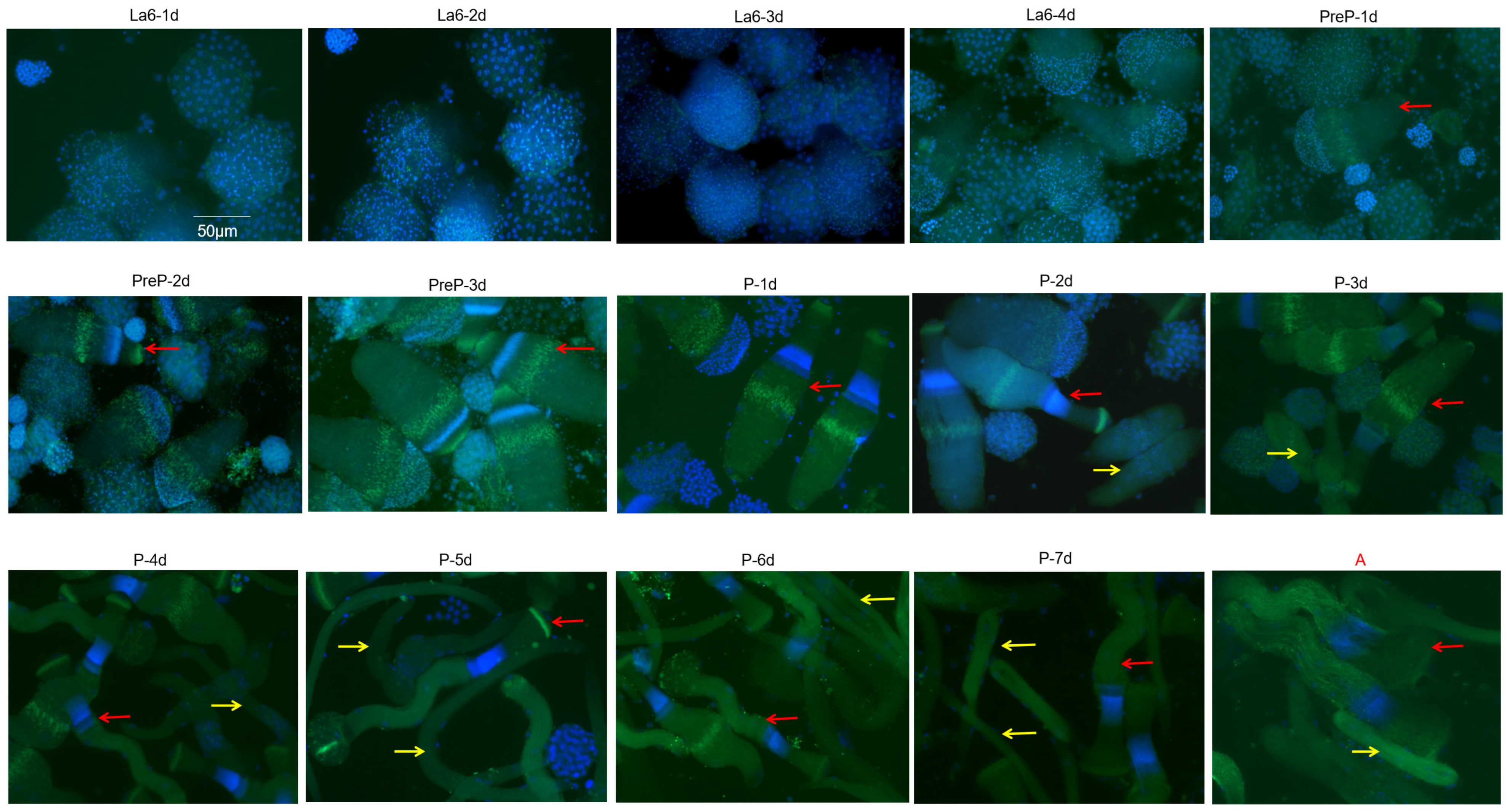

3.1. Elongation and Maturation of Eupyrene Sperm Bundles in S. frugiperda

3.2. Elongation and Maturation of Apyrene Sperm in S. frugiperda

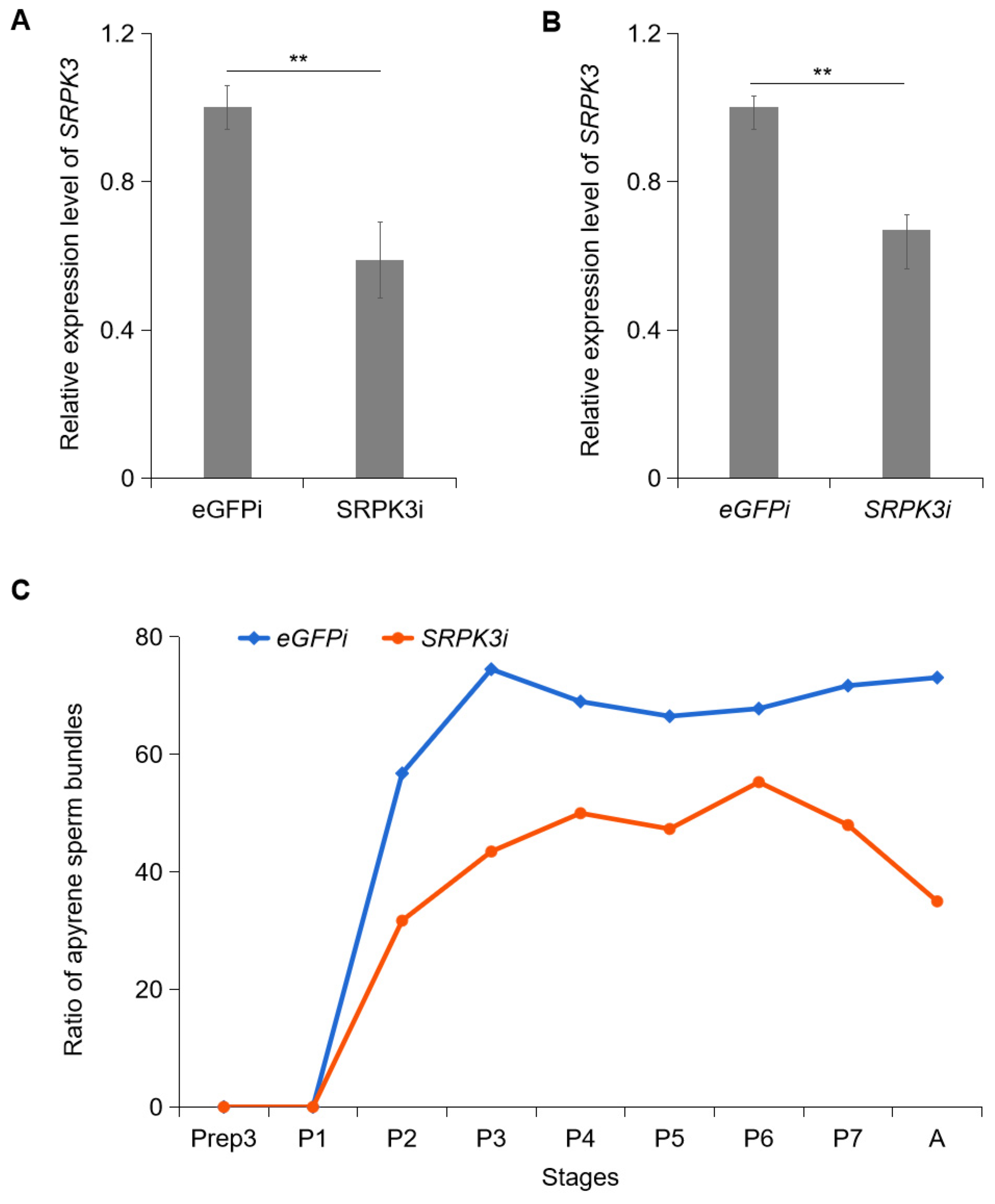

3.3. Knockdown of SRPK3 Impairs the Development of Apyrene Sperm in S. frugiperda

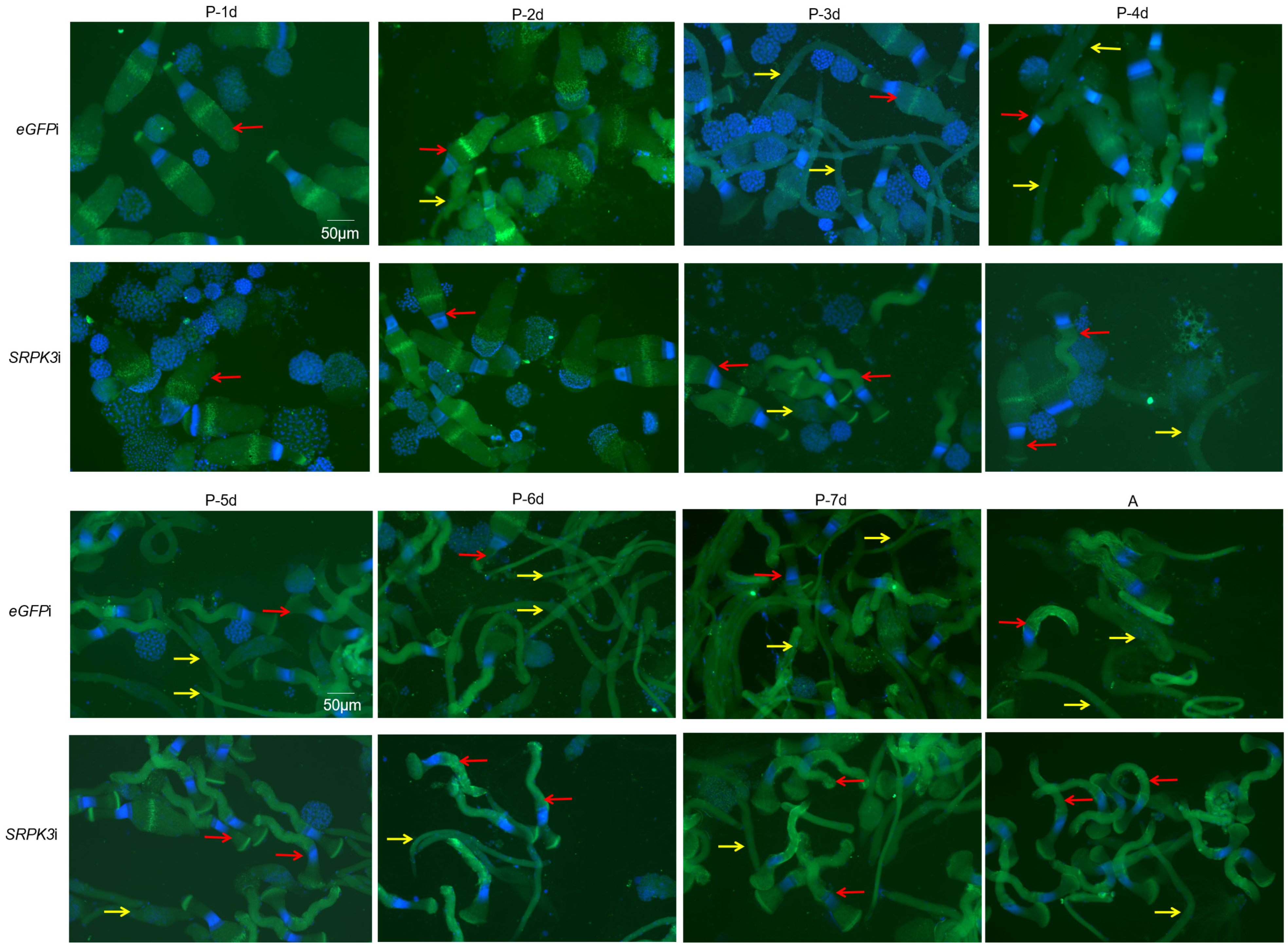

3.4. Morphological Changes in Sperm After SRPK3 Knockdown

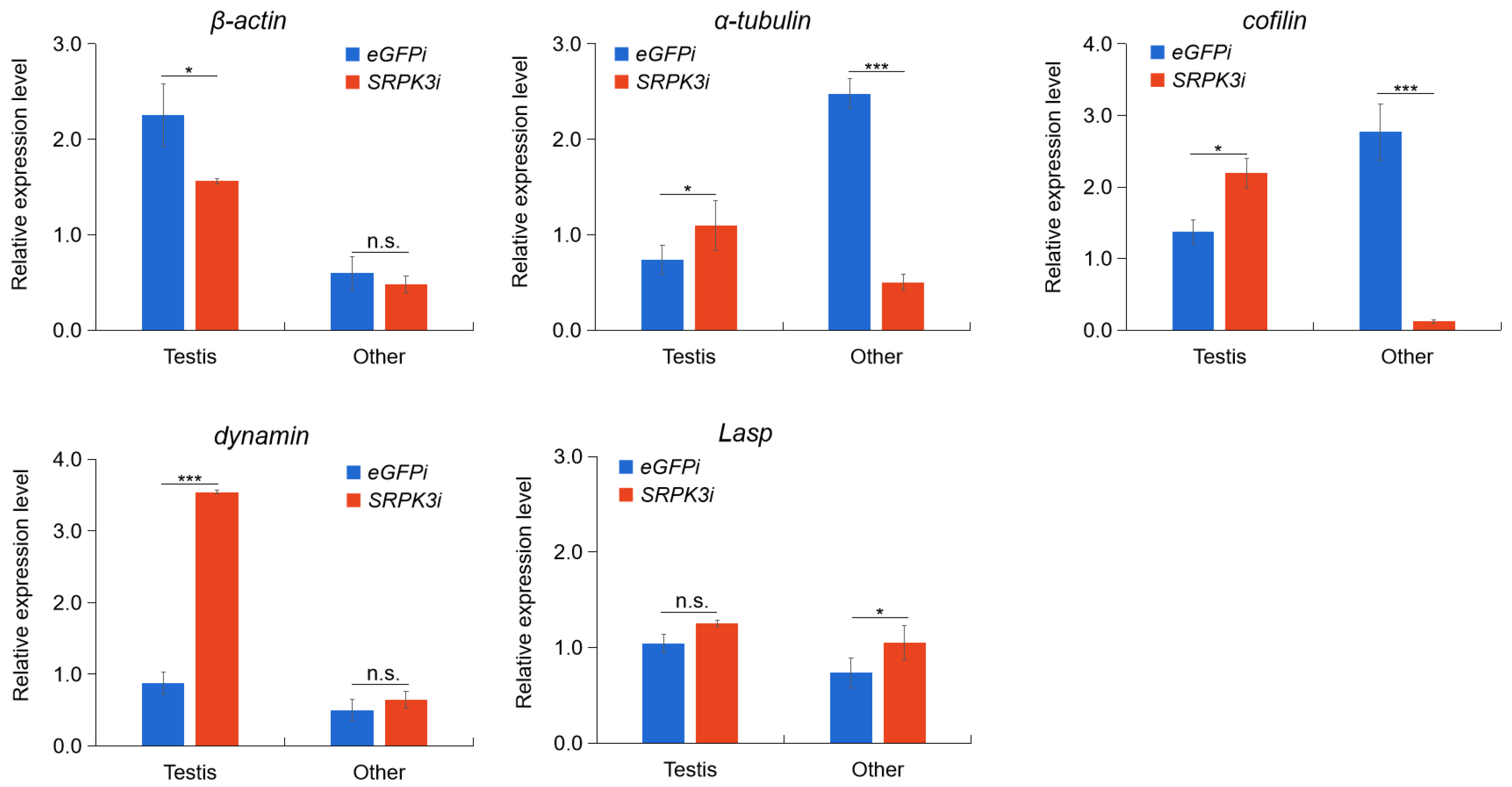

3.5. Altered Expression of Cytoskeletal Genes Following SRPK3 Knockdown

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ashley, T.R.; Wiseman, B.R.; Davis, F.M.; Andrews, K.L. The Fall Armyworm: A Bibliography. Fla. Entomol. 1989, 72, 152–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rane, R.; Walsh, T.K.; Lenancker, P.; Gock, A.; Dao, T.H.; Nguyen, V.L.; Khin, T.N.; Amalin, D.; Chittarath, K.; Faheem, M.; et al. Complex multiple introductions drive fall armyworm invasions into Asia and Australia. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montezano, D.G.; Specht, A.; Sosa-Gómez, D.R.; Roque-Specht, V.F.; Hunt, T. Host Plants of Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in the Americas. Afr. Entomol. 2018, 26, 286–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Liu, Y.; Yang, X.; Liu, Z.; Luo, X.; Xu, J.; Huang, Y. Dysfunction of dimorphic sperm impairs male fertility in the silkworm. Cell Discov. 2020, 6, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seth, R.K.; Yadav, P.; Reynolds, S.E. Dichotomous sperm in Lepidopteran insects: A biorational target for pest management. Front. Insect Sci. 2023, 3, 1198252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balder, P.; Jones, C.; Coward, K.; Yeste, M. Sperm chromatin: Evaluation, epigenetic signatures and relevance for embryo development and assisted reproductive technology outcomes. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2024, 103, 151429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedländer, M. Control of the eupyrene-apyrene sperm dimorphism in Lepidoptera. J. Insect Physiol. 1997, 43, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silberglied, R.E.; Dickinson, S.J.L. Eunuchs: The role of apyrene sperm in Lepidoptera? Am. Nat. 1984, 123, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldschmidt, R. The function of the apyrene spermatozoa. Science 1916, 44, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katsuno, S. Studies on Eupyrene and Apyrene Spermatozoa in the Silkworm, Bombyx mori L. (Lepidoptera: Bombycidae) VIII. The Length of Spermatozoa. Appl. Entomol. Zool. 1978, 13, 127–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osanai, M.; Kasuga, H.; Aigaki, T. Physiological role of apyrene spermatozoa of Bombyx mori. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. CMLS 1987, 43, 593–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, F.T.; Bach, P.V.; Najari, B.B.; Li, P.S.; Goldstein, M. Spermatogenesis in humans and its affecting factors. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2016, 59, 10–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, X.; Hu, B.; Chen, K.; Yu, Y.; Sun, C.; Zhu, D.; Bai, H.; Palli, S.R.; Tan, A. The mechanoreceptor Piezo is required for spermatogenesis in Bombyx mori. BMC Biol. 2024, 22, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Xu, J.; Chen, K.; Liu, Y.; Yang, X.; Tang, L.; Luo, X.; Liu, Z.; Li, M.; Walters, J.R.; et al. BmPMFBP1 regulates the development of eupyrene sperm in the silkworm, Bombyx mori. PLoS Genet. 2022, 18, e1010131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, H.; Oshima, H.; Yuri, K.; Gotoh, H.; Daimon, T.; Yaginuma, T.; Sahara, K.; Niimi, T. Dimorphic sperm formation by Sex-lethal. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 10412–10417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osanai, M.; Kasuga, H.; Aigaki, T. The spermatophore and its structural changes with time in the bursa copulatrix of the silkworm, Bombyx mori. J. Morphol. 1987, 193, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabian, L.; Brill, J.A. Drosophila spermiogenesis: Big things come from little packages. Spermatogenesis 2012, 2, 197–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogat, A.D.; Miller, K.G. A role for myosin VI in actin dynamics at sites of membrane remodeling during Drosophila spermatogenesis. J. Cell Sci. 2002, 115, 4855–4865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mermall, V.; Bonafé, N.; Jones, L.; Sellers, J.R.; Cooley, L.; Mooseker, M.S. Drosophila myosin V is required for larval development and spermatid individualization. Dev. Biol. 2005, 286, 238–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lee, S.; Zhou, L.; Kim, J.; Kalbfleisch, S.; Schöck, F. Lasp anchors the Drosophila male stem cell niche and mediates spermatid individualization. Mech. Dev. 2008, 125, 768–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.H.; Zong, Q.; Du, A.L.; Zhang, W.; Yao, H.C.; Yu, X.Q.; Wang, Y.F. Knockdown of Dynamitin in testes significantly decreased male fertility in Drosophila melanogaster. Dev. Biol. 2016, 420, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh-Roy, A.; Kulkarni, M.; Kumar, V.; Shirolikar, S.; Ray, K. Cytoplasmic dynein-dynactin complex is required for spermatid growth but not axoneme assembly in Drosophila. Mol. Biol. Cell 2004, 15, 2470–2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.G.; Serr, M.; Newman, E.A.; Hays, T.S. The Drosophila tctex-1 light chain is dispensable for essential cytoplasmic dynein functions but is required during spermatid differentiation. Mol. Biol. Cell 2004, 15, 3005–3014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noguchi, T.; Lenartowska, M.; Rogat, A.D.; Frank, D.J.; Miller, K.G. Proper cellular reorganization during Drosophila spermatid individualization depends on actin structures composed of two domains, bundles and meshwork, that are differentially regulated and have different functions. Mol. Biol. Cell 2008, 19, 2363–2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augière, C.; Lapart, J.A.; Duteyrat, J.L.; Cortier, E.; Maire, C.; Thomas, J.; Durand, B. salto/CG13164 is required for sperm head morphogenesis in Drosophila. Mol. Biol. Cell 2019, 30, 636–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács, L.; Nagy, Á.; Pál, M.; Deák, P. Usp14 is required for spermatogenesis and ubiquitin stress responses in Drosophila melanogaster. J. Cell Sci. 2020, 133, jcs237511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balhorn, R. The protamine family of sperm nuclear proteins. Genome Biol. 2007, 8, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, R. Protamines and male infertility. Hum. Reprod. Update 2006, 12, 417–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adenot, P.G.; Szöllösi, M.S.; Geze, M.; Renard, J.P.; Debey, P. Dynamics of paternal chromatin changes in live one-cell mouse embryo after natural fertilization. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 1991, 28, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.T.; Bonneau, A.R.; Giraldez, A.J. Zygotic genome activation during the maternal-to-zygotic transition. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2014, 30, 581–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gou, L.T.; Lim, D.H.; Ma, W.; Aubol, B.E.; Hao, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhao, J.; Liang, Z.; Shao, C.; Zhang, X.; et al. Initiation of Parental Genome Reprogramming in Fertilized Oocyte by Splicing Kinase SRPK1-Catalyzed Protamine Phosphorylation. Cell 2020, 180, 1212–1227.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, J.F.; Lane, W.S.; Fu, X.D. A serine kinase regulates intracellular localization of splicing factors in the cell cycle. Nature 1994, 369, 678–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roscigno, R.F.; Garcia-Blanco, M.A. SR proteins escort the U4/U6.U5 tri-snRNP to the spliceosome. RNA 1995, 1, 692–706. [Google Scholar]

- Hogg, E.K.J.; Findlay, G.M. Functions of SRPK, CLK and DYRK kinases in stem cells, development, and human developmental disorders. FEBS Lett. 2023, 597, 2375–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gui, J.F.; Tronchère, H.; Chandler, S.D.; Fu, X.D. Purification and characterization of a kinase specific for the serine- and arginine-rich pre-mRNA splicing factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1994, 91, 10824–10828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.Y.; Lin, W.; Dyck, J.A.; Yeakley, J.M.; Songyang, Z.; Cantley, L.C.; Fu, X.D. SRPK2: A differentially expressed SR protein-specific kinase involved in mediating the interaction and localization of pre-mRNA splicing factors in mammalian cells. J. Cell Biol. 1998, 140, 737–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koizumi, J.; Okamoto, Y.; Onogi, H.; Mayeda, A.; Krainer, A.R.; Hagiwara, M. The subcellular localization of SF2/ASF is regulated by direct interaction with SR protein kinases (SRPKs). J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 11125–11131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Qiu, J.; Liu, W.; Zhou, Y.; Plocinik, R.M.; Li, H.; Hu, Q.; Ghosh, G.; Adams, J.A.; Rosenfeld, M.G.; et al. The Akt-SRPK-SR axis constitutes a major pathway in transducing EGF signaling to regulate alternative splicing in the nucleus. Mol. Cell 2012, 47, 422–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsianou, D.; Nikolakaki, E.; Tzitzira, A.; Bonanou, S.; Giannakouros, T.; Georgatsou, E. The enzymatic activity of SR protein kinases 1 and 1a is negatively affected by interaction with scaffold attachment factors B1 and 2. FEBS J. 2009, 276, 5212–5227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen-Mahrt, S.K.; Estmer, C.; Ohrmalm, C.; Matthews, D.A.; Russell, W.C.; Akusjärvi, G. The splicing factor-associated protein, p32, regulates RNA splicing by inhibiting ASF/SF2 RNA binding and phosphorylation. EMBO J. 1999, 18, 1014–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, O.; Arnold, M.; Nakagawa, M.; Hamada, H.; Shelton, J.M.; Kusano, H.; Harris, T.M.; Childs, G.; Campbell, K.P.; Richardson, J.A.; et al. Centronuclear myopathy in mice lacking a novel muscle-specific protein kinase transcriptionally regulated by MEF2. Genes Dev. 2005, 19, 2066–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mylonis, I.; Giannakouros, T. Protein kinase CK2 phosphorylates and activates the SR protein-specific kinase 1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003, 301, 650–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassel-Duby, R.; Olson, E.N. Signaling pathways in skeletal muscle remodeling. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2006, 75, 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Yu, W.; Xiong, Y.; Xie, H.; Ren, Z.; Xu, D.; Lei, M.; Zuo, B.; Feng, X. Molecular characterization and expression patterns of serine/arginine-rich specific kinase 3 (SPRK3) in porcine skeletal muscle. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2011, 38, 2903–2909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, L.; Yang, X.; Xu, X.; Yang, D.; Zhu, C.; Yi, M.; Bi, H.; Wang, Y.; Huang, Y. SPSL1 is essential for spermatophore formation and sperm activation Spodoptera frugiperda. PLoS Genet. 2023, 19, e1011073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Bu, L.A.; Zhang, X.Y.; Zhang, Z.R.; Su, S.C.; Guo, D.; Gao, C.F.; Palli, S.R.; Champer, J.; Wu, S.F. β2-tubulin regulates the development and migration of eupyrene sperm in Spodoptera frugiperda. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. CMLS 2025, 82, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Q.; Zhou, J.; Zhu, K.; Zhang, Z.; Dong, H. A simple method for identifying sexuality of Spodoptera frugiperda (J.E. Smith) Pupae and adults. Plant Prot. 2019, 45, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, P.; He, Y.; Zou, L.; Gao, Q.; Xiao, Y. A simple method to identify sex at pre-pupal stages of Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). J. Appl. Entomol. 2024, 148, 703–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods 2001, 25, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stork, N.E. How Many Species of Insects and Other Terrestrial Arthropods Are There on Earth? Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2018, 63, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, J. The Study on the Dichotocarpism Spermatogenesis Related on the Silkworm. Master’s Thesis, Suzhou University, Suzhou, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Day, R.; Abrahams, P.; Bateman, M.; Beale, T.; Clottey, V.; Cock, M.; Colmenarez, Y.; Corniani, N.; Early, R.; Godwin, J.; et al. Oppong-Mensah, BirgittaPhiri, NoahPratt, CorinSilvestri, SilviaWitt, Arne. Fall Armyworm: Impacts and Implications for Africa. Outlooks Pest Manag. 2017, 28, 196–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanule, D.; Balkhande, J.V. Effect of temperature on reproductive and egg laying behavior of silk moth Bombyx mori L. Biosci. Discov. 2013, 4, 15–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, R. The Silk Road: Connecting Cultures, Creating Trust; Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage: Washington, DC, USA, 2002; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Peng, J.; Wu, M.; Sun, A.; Wu, X.; Zheng, J.; Shi, W.; Gao, G. Broad phosphorylation mediated by testis-specific serine/threonine kinases contributes to spermiogenesis and male fertility. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kueng, P.; Nikolova, Z.; Djonov, V.; Hemphill, A.; Rohrbach, V.; Boehlen, D.; Zuercher, G.; Andres, A.C.; Ziemiecki, A. A novel family of serine/threonine kinases participating in spermiogenesis. J. Cell Biol. 1997, 139, 1851–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, Z.; Jha, K.N.; Kim, Y.H.; Vemuganti, S.; Westbrook, V.A.; Chertihin, O.; Markgraf, K.; Flickinger, C.J.; Coppola, M.; Herr, J.C.; et al. Expression analysis of the human testis-specific serine/threonine kinase (TSSK) homologues. A TSSK member is present in the equatorial segment of human sperm. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2004, 10, 433–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Lin, G.; Wei, Y.; Hexige, S.; Niu, Y.; Liu, L.; Yang, C.; Yu, L. TSSK5, a novel member of the testis-specific serine/threonine kinase family, phosphorylates CREB at Ser-133, and stimulates the CRE/CREB responsive pathway. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005, 333, 742–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nozawa, K.; Garcia, T.X.; Kent, K.; Leng, M.; Jain, A.; Malovannaya, A.; Yuan, F.; Yu, Z.; Ikawa, M.; Matzuk, M.M. Testis-specific serine kinase 3 is required for sperm morphogenesis and male fertility. Andrology 2023, 11, 826–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Genes | Forward Primer (5’-3’) | Reverse Primer (5’-3’) |

|---|---|---|

| SRPK3-dsRNA (XM_035588961.2) | GAAATTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCAGGAACCCCTATGTCTGA | GAAATTAATACGACTCACTATAGGCGTCACGGCTATACCCATCT |

| eGFP-dsRNA (MH070103.1) | GAAATTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGTACGGCGTGCAGTGCT | GAAATTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGTGATCGCGCTTCTCG |

| SRPK3 (XM_035588961.2) | AAGAAACGGCATAAACTCGG | GCGTATTGCTCGTCCTCATC |

| actin (KT218672.1) | GATGTCGGGACGGGATA | TCATACGGCGAGTGCTT |

| Cofilin (JX087452.1) | ATCAGGGATGAGAAACAAAT | GTACTCGAAGTCGAAGAGGC |

| Lasp (XM_050702629.1) | AGAGGGCCTCCGCTACACTT | GTCGCTGGCTTCGTAATCGT |

| Dynamin (XM_035574929.2) | GGAAAGAGTTCGGTGTTAGA | CTGGTGATATGCCCTTGTTA |

| β-actin (OK319028.1) | CCACCCTGAGTTCTCCAATG | AGTCTCCTGCCAAAGTCCCT |

| α-tubulin (HQ008728.1) | TACGCCCGTGGTCACTACAC | CTCCAGCTTGGACTTCTTGC |

| EF1α (PV705599.1) | ATCGGTGGTATTGGTACGGT | CCTTGGGTGGGTTGTTCTTG |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Song, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, R.; Zhang, B.; Li, Z.; Liu, X.; Li, D. Knockdown of Serine–Arginine Protein Kinase 3 Impairs Sperm Development in Spodoptera frugiperda. Insects 2025, 16, 1256. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16121256

Song Y, Zhou Y, Wang R, Zhang B, Li Z, Liu X, Li D. Knockdown of Serine–Arginine Protein Kinase 3 Impairs Sperm Development in Spodoptera frugiperda. Insects. 2025; 16(12):1256. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16121256

Chicago/Turabian StyleSong, Yilin, Yi Zhou, Ruoke Wang, Bing Zhang, Zhongwei Li, Xiangyu Liu, and Dandan Li. 2025. "Knockdown of Serine–Arginine Protein Kinase 3 Impairs Sperm Development in Spodoptera frugiperda" Insects 16, no. 12: 1256. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16121256

APA StyleSong, Y., Zhou, Y., Wang, R., Zhang, B., Li, Z., Liu, X., & Li, D. (2025). Knockdown of Serine–Arginine Protein Kinase 3 Impairs Sperm Development in Spodoptera frugiperda. Insects, 16(12), 1256. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16121256