Development of Sarcophaga princeps Wiedemann (Diptera: Sarcophagidae) Under Constant Temperature and Its Implication in Forensic Entomology

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Laboratory Population Establishment

2.2. Observation of Developmental Duration and Measurement of Larval Body Length

2.3. Measurement of Pupal Length, Pupal Width, and Pupal Weight

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

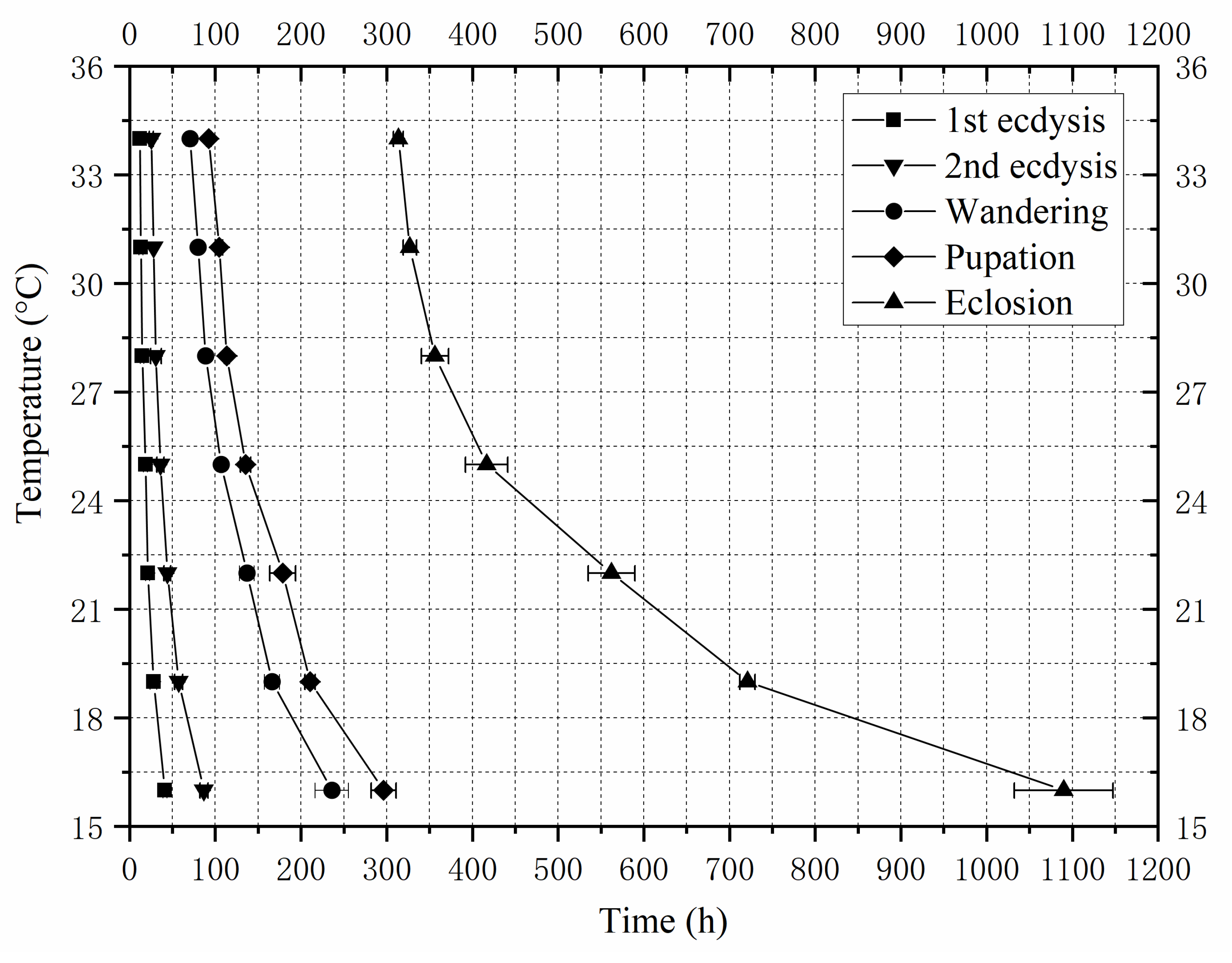

3.1. Developmental Duration and Isomorphen Diagram

3.2. Nonlinear Thermodynamic Optim SSI Model

3.3. Larval Body Length Variation and Isomegalen Diagram

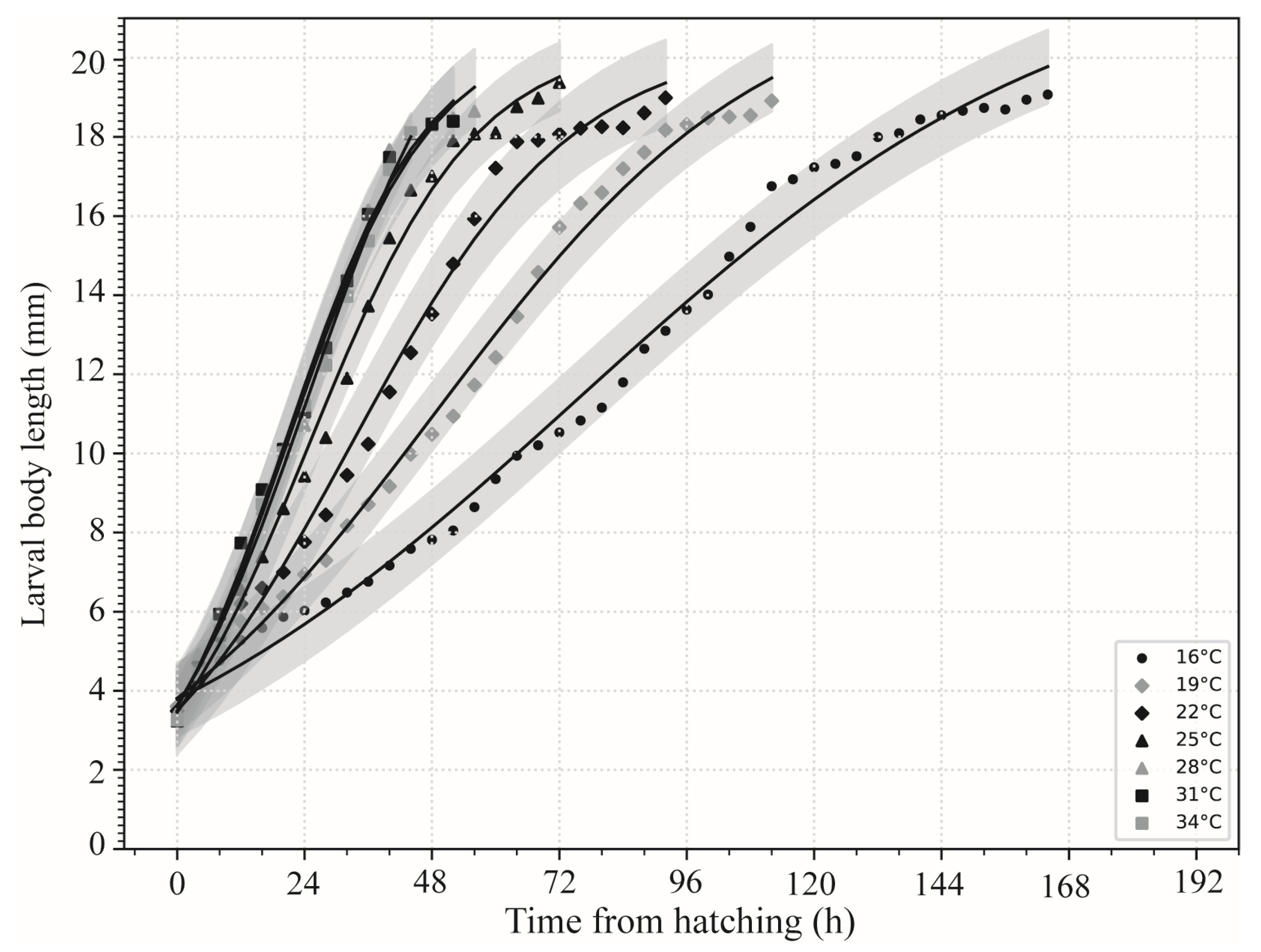

3.4. Pupal Weight, Pupal Length and Pupal Width at Different Constant Temperature

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Amendt, J.; Richards, C.S.; Campobasso, C.P.; Zehner, R.; Hall, M.J.R. Forensic entomology: Applications and limitations. Forensic Sci. Med. Pathol. 2011, 7, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iancu, L.; Sahlean, T.; Davis, T.; Simmons, R. Necrophagous insect species succession on decomposed pig carcasses in North Dakota, USA. J. Med. Entomol. 2024, 61, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, B. Flies as forensic indicators. J. Med. Entomol. 1991, 28, 565–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krosch, M.N.; Johnston, N.P.; Law, K.; Wallman, J.F.; Archer, M.S. Retrospective review of forensic entomology casework in eastern Australia from 1994 to 2022. Forensic Sci. Int. 2025, 367, 112355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matuszewski, S.; Mądra-Bielewicz, A. Field validation of post-mortem interval estimation based on insect development. Part 1: Accuracy gains from the laboratory rearing of insect evidence. Forensic Sci. Int. 2024, 354, 111902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szpila, K.; Mądra, A.; Jarmusz, M.; Matuszewski, S. Flesh flies (Diptera: Sarcophagidae) colonising large carcasses in Central Europe. Parasitol. Res. 2015, 114, 2341–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Guo, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, Y.; Kang, C.; Hu, G.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J. Succession patterns of sarcosaprophagous insects on pig carcasses in different months in Yangtze River Delta, China. Forensic Sci. Int. 2023, 342, 111518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamany, A.S.; Elkhadragy, M.F.; Abdel-Gaber, R. Wohlfahrtia nuba (Wiedemann, 1830) (Diptera: Sarcophagidae) development and survival under fluctuating temperatures. Insects 2025, 16, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang, Y.; Amendt, J.; Wang, Y.; Ren, L.; Yang, F.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, C.; Guo, Y. Multimethod combination for age estimation of Sarcophaga peregrina (Diptera: Sarcophagidae) with implications for estimation of the postmortem interval. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2023, 137, 329–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VanLaerhoven, S.L.; Merritt, R.W. 50 years later, insect evidence overturns Canada’s most notorious case—Regina v. Steven Truscott. Forensic Sci. Int. 2019, 301, 326–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vairo, K.P.; Caneparo, M.F.D.C.; Corrêa, R.C.; Preti, D.; Moura, M.O. Can Sarcophagidae (Diptera) be the most important entomological evidence at a death scene? Microcerella halli as a forensic indicator. Rev. Bras. Entomol. 2017, 61, 275–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanford, M.R. Insects and associated arthropods analyzed during medicolegal death investigations in Harris County, Texas, USA: January 2013–April 2016. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0179404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasconcelos, S.D.; Soares, T.F.; Costa, D.L. Multiple colonization of a cadaver by insects in an indoor environment: First record of Fannia trimaculata (Diptera: Fanniidae) and Peckia (Peckia) chrysostoma (Sarcophagidae) as colonizers of a human corpse. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2014, 128, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, S.K. Study of life cycle of Seniorwhitea reciproca (Walker) (Diptera: Sarcophagidae) on coastal fish Panna microdon (Bleeker) in laboratory conditions. Rec. Zool. Surv. India 2009, 109, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z. The Keys of Common Flies of China, 2nd ed.; Science Press: Beijing, China, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C. Taxonomic Study of Sarcophaga in China (Diptera: Sarcophagidae). Ph.D. Thesis, Beijing Forestry University, Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bharti, M.; Singh, D.; Singh Sidhu, I. First record of some carrion flies (Diptera: Cyclorrhapha) from India. Uttar Pradesh J. Zool. 2001, 21, 267–268. [Google Scholar]

- Kumara, T.K.; Disney, R.H.L.; Hassan, A.A.; Flores, M.; Hwa, T.S.; Mohamed, Z.; CheSalmah, M.R.; Bhupinder, S. Occurrence of oriental flies associated with indoor and outdoor human remains in the tropical climate of north Malaysia. J. Vector Ecol. 2012, 37, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szpila, K.; Voss, J.G.; Pape, T. A new dipteran forensic indicator in buried bodies. Med. Vet. Entomol. 2010, 24, 278–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AL-Mekhlafi, F.A.; Al-Zahrani, O.; Al-Qahtni, A.H.; Al-Khalifal, M.S. Decomposition of buried rabbits and pattern succession of insect arrival on buried carcasses. Int. J. Trop. Insect Sci. 2024, 44, 1037–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, M.; Qi, X.; Shi, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Yang, T.; Ren, J.; Liu, F.; Zhang, G.; et al. Predicting the postmortem interval of burial cadavers based on microbial community succession. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2021, 52, 102488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonacci, T.; Mendicino, F.; Bonelli, D.; Carlomagno, F.; Curia, G.; Scapoli, C.; Pezzi, M. Investigations on arthropods associated with decay stages of buried animals in Italy. Insects 2021, 12, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, S.H.; Rizman-Idid, M.; Mohd-Aris, E.; Kurahashi, H.; Mohamed, Z. DNA-based characterisation and classification of forensically important flesh flies (Diptera: Sarcophagidae) in Malaysia. Forensic Sci. Int. 2010, 199, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, M.; Singh, D.; Sharma, A.K. Molecular identification of two forensically important Indian flesh flies (Diptera: Sarcophagidae). Int. J. Adv. Res. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2015, 2, 814–818. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Hu, G.; Kang, C.; Chen, J.; Wang, J.; et al. A novel mathematical model and application software for estimating the age of necrophagous fly larvae. Forensic Sci. Int. 2024, 354, 111894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikemoto, T.; Kiritani, K. Novel method of specifying low and high threshold temperatures using thermodynamic SSI Model of insect development. Environ. Entomol. 2019, 48, 479–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Shang, Y.; Ren, L.; Chen, W.; Wang, S.; Guo, Y. Development of Sarcophaga dux (Diptera: Sarcophagidae) at constant temperatures and differential gene expression for age estimation of the pupae. J. Therm. Biol. 2020, 93, 102735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matuszewski, S.; Mądra-Bielewicz, A. Field validation of post-mortem interval estimation based on insect development. Part 2: Pre-appearance interval, expert evidence selection and accuracy baseline data. Forensic Sci. Int. 2025, 367, 112316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, G.D.S.; Oliveira-Costa, J.; De Mello-Patiu, C.A. New records of Sarcophagidae species (Diptera) with forensic potential in Rio de Janeiro. Rev. Bras. Entomol. 2015, 59, 255–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vairo, K.P.E.; Ururahy-Rodrigues, A.; Osvaldo Moura, M.; Antunes De Mello-Patiu, C. Sarcophagidae (Diptera) with forensic potential in Amazonas: A pictorial key. Trop. Zool. 2014, 27, 140–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garção-Neto, C.H.; Cortinhas, L.B.; Mendonça, P.M.; Duarte, M.L.; Martins, R.T.; De Carvalho Queiroz, M.M. Dipteran succession on decomposing domestic pig carcasses in a rural area of southeastern Brazil. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 18496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Barros, S.E.G.; Bicho, C.D.L.; Ferreira, H.R.P.; Vasconcelos, S.D. Death, flies and environments: Towards a qualitative assessment of insect (Diptera) colonization of human cadavers retrieved from sites of death in Brazil. Forensic Sci. Int. 2024, 365, 112241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defilippo, F.; Bonilauri, P.; Dottori, M. Effect of temperature on six different developmental landmarks within the pupal stage of the forensically important blowfly Calliphora vicina (Robineau–Desvoidy) (Diptera: Calliphoridae). J. Forensic Sci. 2013, 58, 1554–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yang, L.; Tao, L.; Wang, J. Development of Chrysomya megacephala at constant temperatures within its colony range in Yangtze River Delta region of China. Forensic Sci. Res. 2018, 3, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, G.; Wang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, M.; Wang, J. Development of Chrysomya rufifacies (Diptera: Calliphoridae) at constant temperatures within its colony range in Yangtze River Delta Region of China. J. Med. Entomol. 2019, 56, 1215–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Wang, Y.; Hu, G.; Wang, Y.; Xu, W.; Wu, M.; Wang, J. Development of Lucilia sericata (Diptera: Calliphoridae) under constant temperatures and its significance for the estimation of time of death. J. Med. Entomol. 2020, 57, 1373–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, J.F.; Zhang, Y.N.; Tao, L.Y.; Wang, M. Forensically important Boettcherisca peregrina (Diptera: Sarcophagidae) in China: Development pattern and significance for estimating postmortem interval. J. Med. Entomol. 2017, 54, 1491–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, L.; Wang, J.; Wang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Chu, J.; Liu, K.; Hou, Y.; Tao, L. Temperature–dependent development of Parasarcophaga similis (meade 1876) and its significance in estimating postmortem interval. J. Forensic Sci. 2017, 62, 1234–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grassberger, M.; Reiter, C. Effect of temperature on development of Liopygia (=Sarcophaga) argyrostoma (Robineau-Desvoidy) (Diptera: Sarcophagidae) and its forensic implications. J. Forensic Sci. 2002, 47, 1332–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbosa, T.M.; Cruz, M.R.P.; Pontes, W.J.T.; Vasconcelos, S.D. Aspects of the reproductive behaviour and development of two forensically relevant species, Blaesoxipha (Gigantotheca) stallengi (Lahille, 1907) and Sarcophaga (Liopygia) ruficornis (Fabricius, 1794) (Diptera: Sarcophagidae). Rev. Bras. Entomol. 2019, 63, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesne, P.; Srivastav, S.P.; El-Hefnawy, A.; Parrott, J.J.; Sanford, M.R.; Tarone, A.M. Facultative Viviparity in a Flesh Fly (Diptera: Sarcophagidae): Forensic Implications of High Variability in Rates of Oviparity in Blaesoxipha plinthopyga (Diptera: Sarcophagidae). J. Med. Entomol. 2020, 57, 697–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, J.-A.; Anderson, G.S. Effect of Fluctuating Temperatures on the Development of a Forensically Important Blow Fly, Protophormia terraenovae (Diptera: Calliphoridae). Env. Entomol 2013, 42, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, R.; Gao, Y.; Shao, S.; Liu, S.; Wang, Y. Effect of fluctuating temperatures on the development of forensically important fly species, Chrysomya megacephala (Diptera: Calliphoridae). Forensic Sci. Int. 2025, 367, 112373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang, Y.; Yang, F.; Ngando, F.J.; Zhang, X.; Feng, Y.; Ren, L.; Guo, Y. Development of Forensically Important Sarcophaga peregrina (Diptera: Sarcophagidae) and Intra-Puparial Age Estimation Utilizing Multiple Methods at Constant and Fluctuating Temperatures. Animals 2023, 13, 1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Temperatures | First Ecdysis | Second Ecdysis | Wandering | Pupariation | Eclosion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 °C | 41.33 ± 2.31 | 86.67 ± 4.62 | 236.00 ± 19.52 | 296.33 ± 14.43 | 1090.00 ± 57.65 |

| 19 °C | 28.00 ± 4.00 | 57.33 ± 4.62 | 166.33 ± 8.74 | 210.67 ± 6.11 | 721.00 ± 8.72 |

| 22 °C | 21.33 ± 2.31 | 44.00 ± 4.00 | 137.00 ± 8.66 | 178.67 ± 15.28 | 562.33 ± 27.21 |

| 25 °C | 18.67 ± 2.31 | 36.00 ± 4.00 | 107.00 ± 4.00 | 135.33 ± 5.86 | 416.67 ± 27.70 |

| 28 °C | 14.67 ± 2.31 | 30.67 ± 6.11 | 88.67 ± 3.21 | 113.33 ± 2.89 | 356.33 ± 16.01 |

| 31 °C | 13.33 ± 2.31 | 28.00 ± 0.00 | 80.00 ± 2.00 | 104.67 ± 4.16 | 327.00 ± 7.94 |

| 34 °C | 12.00 ± 0.00 | 25.33 ± 2.31 | 70.67 ± 4.62 | 92.33 ± 2.52 | 313.67 ± 5.69 |

| Parameter (Unit) | 1st Ecdysis | 2nd Ecdysis | Wandering | Pupariation | Eclosion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TΦ (℃) | 20.83 | 21.91 | 21.25 | 21.73 | 21.85 |

| ρΦ (day−1) | 0.99 | 0.53 | 0.17 | 0.14 | 0.04 |

| ∆HA (cal/mol) | 1.31 × 104 | 1.32 × 104 | 1.27 × 104 | 1.24 × 104 | 1.44 × 104 |

| ∆HL (cal/mol) | −1.14 × 105 | −7.26 × 104 | −8.15 × 104 | −5.75 × 105 | −7.87 × 104 |

| ∆HH (cal/mol) | 4.47 × 104 | 4.94 × 104 | 4.25 × 104 | 4.53 × 104 | 5.44 × 104 |

| TL (℃) | 12.13 | 10.49 | 10.40 | 7.86 | 11.11 |

| TH (℃) | 38.3 | 37.20 | 39.17 | 38.83 | 35.88 |

| χ2 | 8.20 × 10−3 | 5.21 × 10−3 | 6.03 × 10−4 | 1.01 × 10−3 | 2.82 × 10−4 |

| R2 | 0.993 | 0.991 | 0.997 | 0.993 | 0.994 |

| Model | SE | |

|---|---|---|

| / | (1) | |

| ±0.2600 | (2a) | |

| ±0.8589 | (2b) | |

| ±0.0025 | (2c) |

| Temperatures | Pupal Body Weight (g) | Pupal Body Length (mm) | Pupal Body Width (mm) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Max | Min | Avg ± SD | Max | Min | Avg ± SD | Max | Min | Avg ± SD | |

| 34 °C | 0.1281 | 0.0651 | 0.0944 ± 0.0145 | 11.67 | 9.65 | 10.65 ± 0.1877 | 4.73 | 3.74 | 4.27 ± 0.2218 |

| 31 °C | 0.1395 | 0.0660 | 0.0991 ± 0.0157 | 11.63 | 9.65 | 10.67 ± 0.5261 | 4.82 | 3.84 | 4.27 ± 0.2165 |

| 28 °C | 0.1442 | 0.0838 | 0.1117 ± 0.0113 | 12.15 | 9.95 | 10.84 ± 0.4902 | 4.63 | 3.96 | 4.31 ± 0.1662 |

| 25 °C | 0.1385 | 0.0866 | 0.1106 ± 0.0125 | 11.96 | 9.49 | 10.69 ± 0.4885 | 4.96 | 3.88 | 4.33 ± 0.2503 |

| 22 °C | 0.1357 | 0.0778 | 0.1097 ± 0.0135 | 12.34 | 9.54 | 10.76 ± 0.5148 | 4.81 | 3.93 | 4.42 ± 0.2251 |

| 19 °C | 0.1351 | 0.0745 | 0.1009 ± 0.0151 | 12.09 | 9.13 | 10.82 ± 0.6631 | 4.91 | 3.92 | 4.50 ± 0.2208 |

| 16 °C | 0.1302 | 0.0731 | 0.1088 ± 0.0122 | 11.70 | 9.39 | 10.41 ± 0.4312 | 4.69 | 3.99 | 4.33 ± 0.1608 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, L.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, G.; Zhuo, Y.; Jin, J.; Fang, Q.; Li, X.; Li, S.; Wang, Y. Development of Sarcophaga princeps Wiedemann (Diptera: Sarcophagidae) Under Constant Temperature and Its Implication in Forensic Entomology. Insects 2025, 16, 1153. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16111153

Li L, Zhang Y, Hu G, Zhuo Y, Jin J, Fang Q, Li X, Li S, Wang Y. Development of Sarcophaga princeps Wiedemann (Diptera: Sarcophagidae) Under Constant Temperature and Its Implication in Forensic Entomology. Insects. 2025; 16(11):1153. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16111153

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Liangliang, Yingna Zhang, Gengwang Hu, Yumeng Zhuo, Jianjun Jin, Qiang Fang, Xuebo Li, Shujin Li, and Yu Wang. 2025. "Development of Sarcophaga princeps Wiedemann (Diptera: Sarcophagidae) Under Constant Temperature and Its Implication in Forensic Entomology" Insects 16, no. 11: 1153. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16111153

APA StyleLi, L., Zhang, Y., Hu, G., Zhuo, Y., Jin, J., Fang, Q., Li, X., Li, S., & Wang, Y. (2025). Development of Sarcophaga princeps Wiedemann (Diptera: Sarcophagidae) Under Constant Temperature and Its Implication in Forensic Entomology. Insects, 16(11), 1153. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16111153