Dung Beetles, Dung Burial, and Plant Growth: Four Scarabaeoid Species and Sorghum

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site and Biological Material

2.2. Soil Preparation and Experimental Set-Up

2.3. Measurements of Physico-Chemical Parameters and Plant Growth

2.4. Chlorophyll and Carotenoids Measurements

2.5. Leaf Water Content

2.6. Soil Physico-Chemical Properties

2.7. Enzymatic Activities

2.8. Microbial Load

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

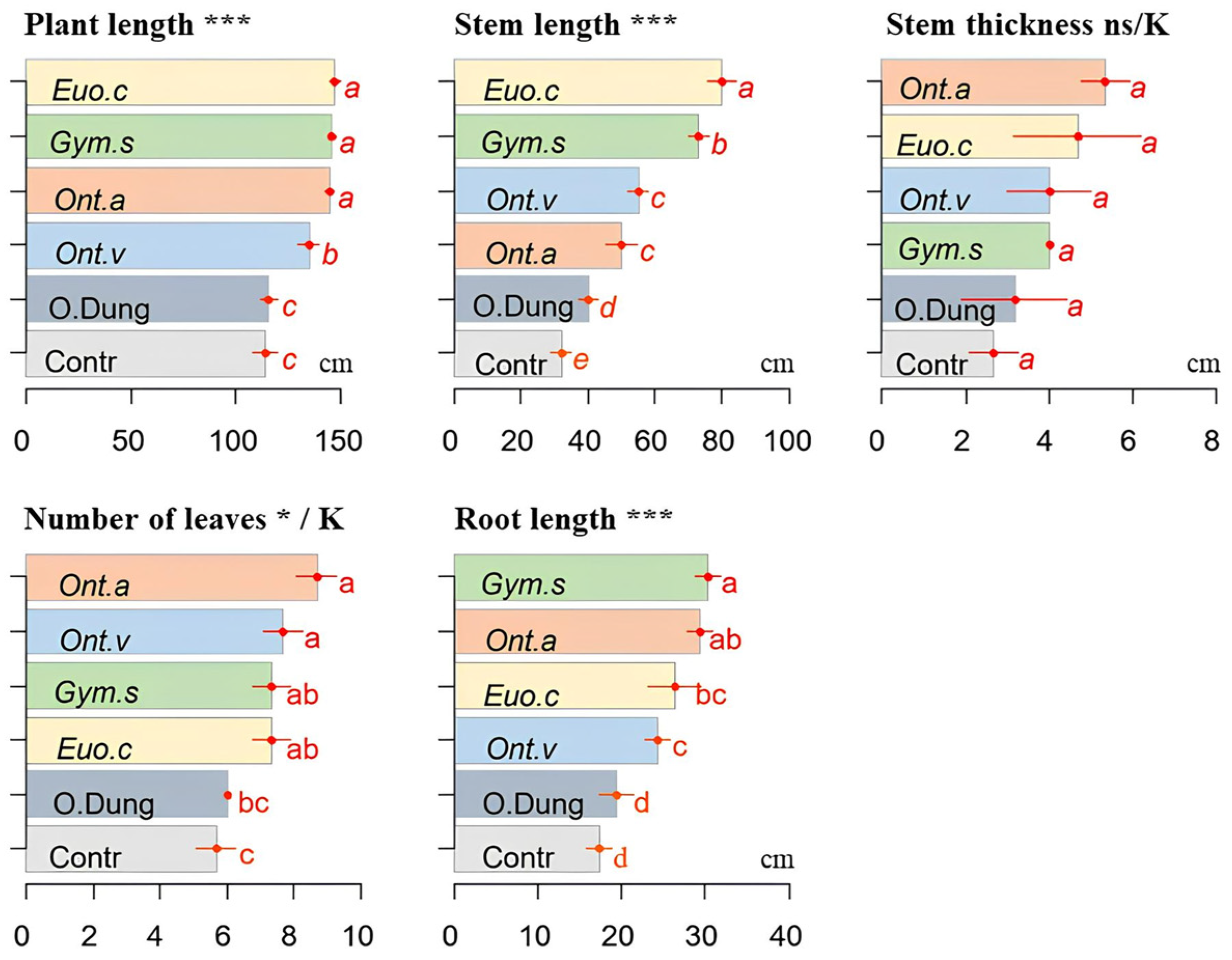

3.1. Agronomic Parameters

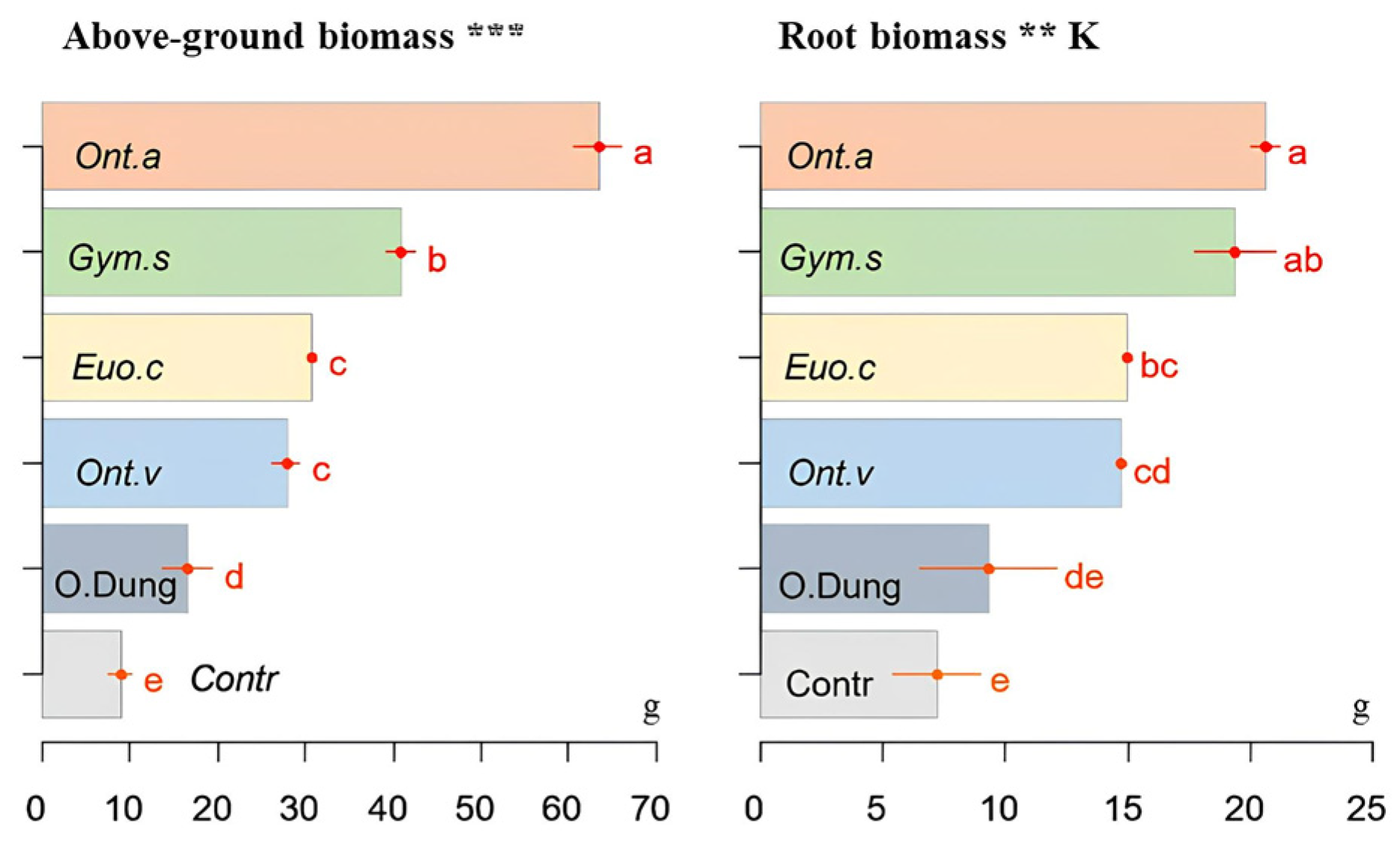

3.2. Biomass of Plants

3.3. Leaf Area and Water Content

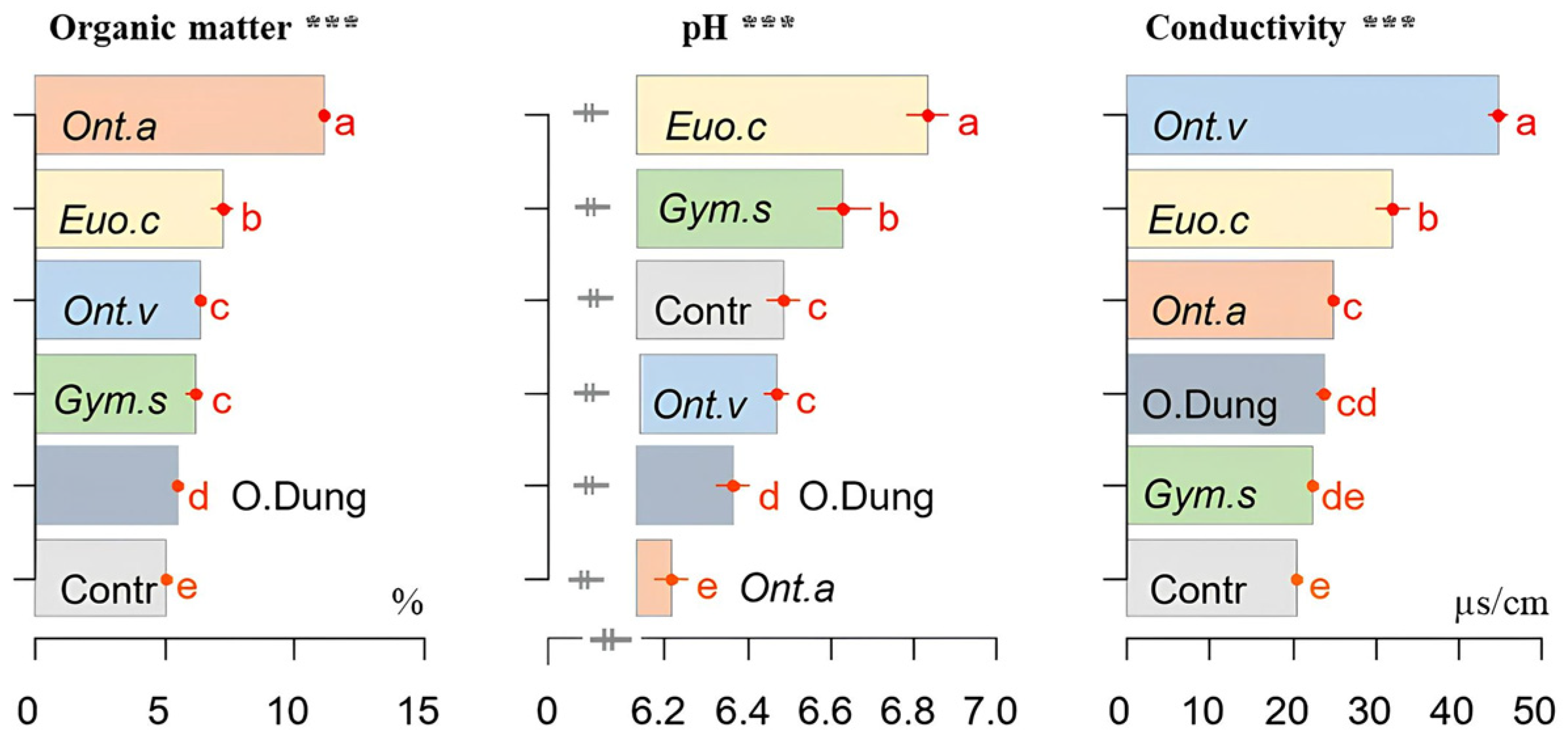

3.4. pH, Conductivity, and Soil Organic Matter

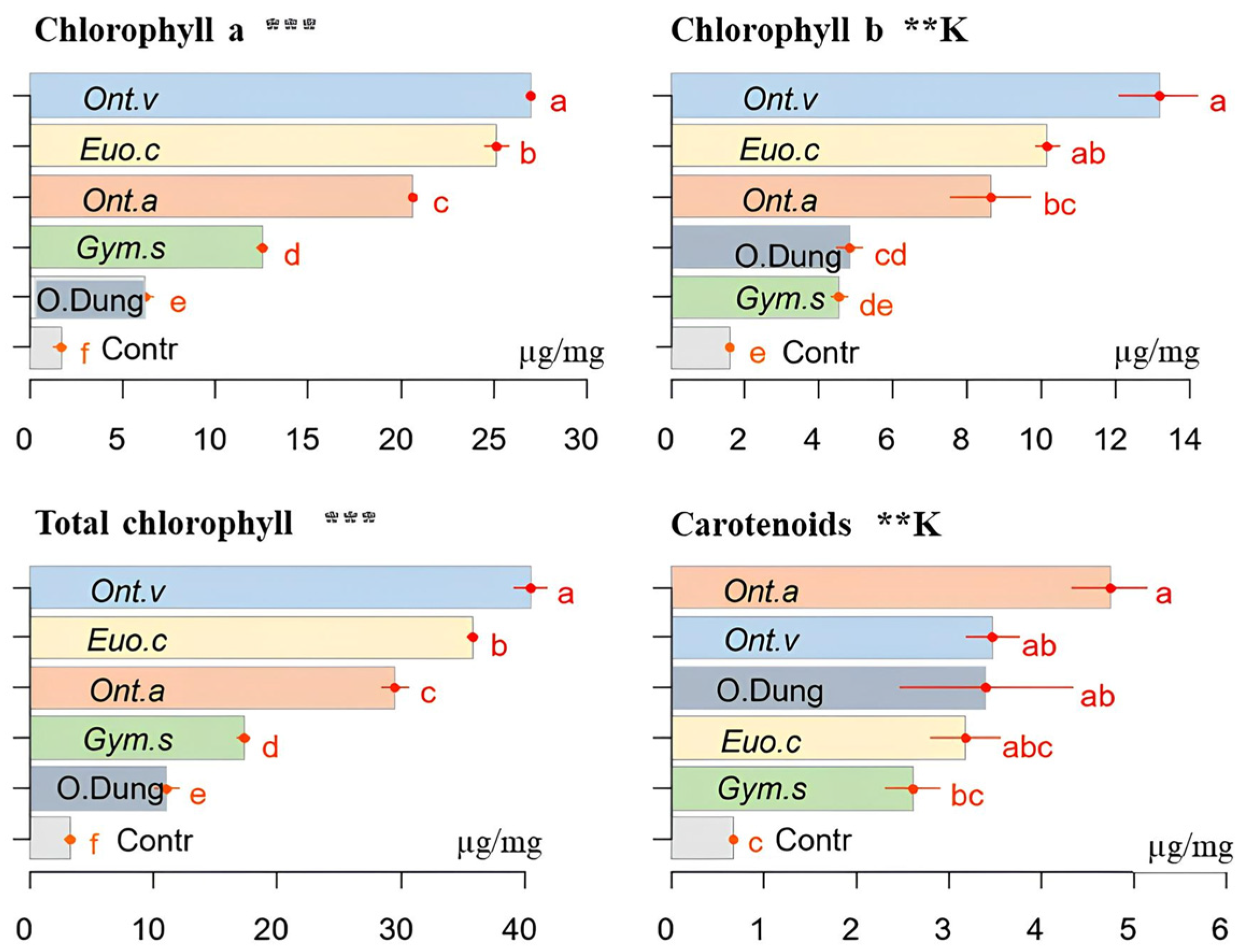

3.5. Chlorophylls and Carotenoids

3.6. Enzymatic Activity and Microbial Load

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- De Farias, P.M.; Hernández, M.I.M. Dung Beetles Associated with Agroecosystems of Southern Brazil: Relationship with Soil Properties. Rev. Bras. Cienc. Solo 2017, 41, e0160248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrios, E. Soil biota, ecosystem services and land productivity. Ecol. Econ. 2007, 64, 269–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanafy, H.E.M.; El-Sayed, W. Soil nutrient as affected by activity of dung beetles, Scarabaeus sacer (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae) and toxicity of certain herbicides on beetles. J. Appl. Sci. Res. 2012, 8, 4752–4758. [Google Scholar]

- Nichols, E.; Spector, S.; Louzada, J.; Larsen, T.; Amezquita, S.; Favila, M.E. Ecological functions and ecosystem services provided by Scarabaeinae dung beetles. Biol. Conserv. 2008, 141, 1461–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slade, E.M.; Roslin, T.; Santalahti, M.; Bell, T. Disentangling the ‘brown world’ faecal–detritus interaction web: Dung beetle effects on soil microbial properties. Oikos 2016, 125, 629–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, H.S.; Lee, J.-H.; Kwon, O.S.; Na, Y.E.; Jang, Y.S.; Kim, W.H. Effects of paracoprid dung beetles (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae) on the growth of pasture herbage and on the underlying soil. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2005, 29, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, I.C. Natural manuring and soil conditioning by dung beetles. Trop. Ecol. 1993, 34, 150–159. [Google Scholar]

- Bornemissza, G.F.; Williams, C.H. An effect of dung beetle activity on plant yield. Pedobiologia 1970, 10, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbiati, C.; Bensi, C.; Conceição, C.H.C.; Florcovski, J.L.; Calafiori, M.H. Estudo comparativo entre besouros do esterco, Dichotomius analypticus (Mann, 1829) e Onthophagus gazella (F.), sobre as pastagens, em condições brasileiras. Ecossistema 1995, 20, 109–118. [Google Scholar]

- Kabir, S.M.H.; Howlader, A.J.; Begum, J. Effect of dung beetle activities on the growth and yield of wheat plants. Bangladesh J. Agric. Res. 1985, 10, 49–55. [Google Scholar]

- Lastro, E. Dung Beetles (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae and Geotrupidae) in North Carolina Pasture Ecosystem. Master’s Thesis, Entomology, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rougon, D. Coléoptères Coprophiles en Zone Sahélienne: Étude Biocénotique, Comportement Nidificateur, Intervention Dans Le recyclage de la Matière Organique du sol. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Orléans, Orléans, France, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Macqueen, A.; Beirne, B.P. Effects of cattle dung and dung beetle activity on growth of beardless wheatgrass in British Columbia. Can. J. Plant Sci. 1975, 55, 961–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hajji, H.; Janati-Idrissi, A.; Taybi, A.F.; Lumaret, J.-P.; Mabrouki, Y. Contribution of dung beetles to the enrichment of soil with organic matter and nutrients under controlled conditions. Diversity 2024, 16, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rougon, D.; Rougon, C.; Levieux, J.; Trichet, J. Variations in the amino-acid content in zebu dung in the Sahel during nesting by dung-beetles (Coleoptera, Scarabaeidae). Soil Biol. Biochem. 1990, 22, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rougon, D.; Rougon-Chassary, C. Nidification des Scarabaeidae et cleptoparasitisme des Aphodiidae en zone sahélienne (Niger). Leur rôle dans la fertilisation des sols sableux [Col.]. Bull. Soc. Entomol. Fr. 1983, 88, 496–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadiri, M.; Ater, M. Diversité des variétés « locales » du sorgho grain (Sorghum bicolor Moench L.) au nord-ouest du Maroc. In Ressources Phytogénétiques et Développement Durable. Actes du Séminaire National sur la Biodiversité Végétale, Organisé sous L’égide du MAMVA et du Min. Env. Rabat, 24 au 26 Octobre 1994; Birouk, A., Rejdali, M., Eds.; Actes Editions: Rabat, Maroc, 1997; pp. 203–218. [Google Scholar]

- Janati, A. Les cultures fourragères dans les oasis. In Les Systèmes Agricoles Oasiens, Options Méditerranéennes: Série A. Séminaires Méditerranéens; Ciheam: Montpellier, France, 1990; pp. 163–169. [Google Scholar]

- Cheik, S.; Jouquet, P. Integrating local knowledge into soil science to improve soil fertility. Soil Use Manag. 2020, 36, 561–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, D.; Lepage, M.; Konaté, S.; Linsenmair, K.E. Ecosystem services of termites (Blattoidea: Termitoidae) in the traditional soil restoration and cropping system Zaï in northern Burkina Faso (West Africa). Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2017, 236, 198–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fall, F.B. Évaluation Agro-Morphologique et Physiologique d’une Population « Stay Green » de Sorgho [Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench] Pour la Tolérance au Stress Hydrique Post-Floral. Master’s Thesis, Aménagement et Gestion Durable des Écosystèmes Forestiers et Agroforestiers (AGDEFA), Assane-Seck University, Ziguinchor, Sénégal, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Madre, J.-F. Mesurim Pro, Version 3.4 (Fr). Licence libre GNU. Académie d’Amiens, Institut Français de l’Éducation et Groupe Technique de l’Information et de la Communication en SVT. 2013. Available online: https://acces.ens-lyon.fr/acces/logiciels/applications/mesurim (accessed on 28 November 2024).

- Arnon, D.I. Copper enzymes in isolated chloroplasts. Polyphenoloxidase in Beta vulgaris. Plant Physiol. 1949, 24, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, G.; Teicher, K. Ein kolorimetrisches Verfahren zur Bestimmung der Ureaseaktivität in Böden. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 1961, 95, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabatabai, M.A.; Bremner, J.M. Use of p-nitrophenyl phosphate for assay of soil phosphatase activity. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1969, 1, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zantua, M.I.; Bremner, J.M. Preservation of soil samples for assay of urease activity. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1975, 7, 297–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, M.S. Introduction to Soil Microbiology: An Exploratory Approach; Current Topics in Soil Microbiology 10; Delmar Publishers: Albany, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Torsvik, V.; Øvreås, L. Microbial diversity and function in soil: From genes to ecosystems. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2002, 5, 240–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borcard, D.; Gillet, F.; Legendre, P. Numerical Ecology with R, 2nd ed.; Springer International: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, K.K.; Aneja, K.R.; Rana, D. Current status of cow dung as a bioresource for sustainable development. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2016, 3, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghesio, L.; Luzzatto, M.; Palestrini, C. Interactions between dung, plants and the dung fauna in a heathland in northern Italy. Pedobiologia 1999, 43, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyman, H.A. Rangeland degradation in a semi-arid South Africa—I: Influence on seasonal root distribution, root/shoot ratios and water-use efficiency. J. Arid. Environ. 2005, 60, 457–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, D.; Imura, O.; Shi, K.; Shibuya, T. Effect of tunneler dung beetles on cattle dung decomposition, soil nutrients and herbage growth. Grassl. Sci. 2007, 53, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, C.H.B.; Santos, J.C.C.; Bianchin, I. Contribuição de Onthophagus gazella à melhoria da fertilidade do solo pelo enterrio de massa fecal bovina fresca. Rev. Bras. Zootec. 1998, 27, 681–685. [Google Scholar]

- Ai, C.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, X.; Guo, D.; Zhou, W.; Huang, S. Distinct responses of soil bacterial and fungal communities to changes in fertilization regime and crop rotation. Geoderma 2018, 319, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Agarwal, S.K. Growth and yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum) as influenced by levels of farmyard manure and nitrogen. Indian J. Agron. 2001, 46, 462–467. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, J.; Scholtz, C.H.; Janeau, J.-L.; Grellier, S.; Podwojewski, P. Dung beetles (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae) can improve soil hydrological properties. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2010, 46, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaleri, A.R.; Ma, J.; Abro, S.; Faqir, Y.; Nabi, F.; Hakeem, A.; Jakhar, A.; Ahmed, A.; Ahmed, S.; Qing, Y.; et al. Dung beetle improves soil bacterial diversity and enzyme activity and enhances growth and antioxidant content of Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa ssp. pekinensis). J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2021, 21, 3387–3401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Hong, X.; Hu, K.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Du, S.; Li, Y.; Hu, D.; Cheng, K.; An, B.; et al. Impaired magnesium protoporphyrin IX methyltransferase (ChlM) impedes chlorophyll synthesis and plant growth in rice. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tixier, T.; Bloor, J.M.G.; Lumaret, J.-P. Species-specific effects of dung beetle abundance on dung removal and leaf litter decomposition. Acta Oecol. 2015, 69, 31–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Lashari, M.; Liu, X.; Ji, H.; Li, L.; Zheng, J.; Kibue, G.; Joseph, S.; Cheng, K. Changes in soil microbial community structure and enzyme activity with amendment of biochar-manure compost and pyroligneous solution in a saline soil from Central China. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2015, 70, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menéndez, R.; Webb, P.; Orwin, K. Complementarity of dung beetle species with different functional behaviours influence dung-soil carbon cycling. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2016, 92, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Huang, Y.; Wang, H.; Shen, Z.; Cece, Q.; Rong, L.; Shen, Q. Enzymatic activities triggered by the succession of microbiota steered fiber degradation and humification during co-composting of chicken manure and rice husk. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 258, 110014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nourbakhsh, F.; Monreal, C. Effects of soil properties and trace metals on urease activities of calcareous soils. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2004, 40, 359–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, P.; Das, S.; Shankhdhar, D.; Shankhdhar, S. Phosphate-solubilizing microorganisms: Mechanism and their role in phosphate solubilization and uptake. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2020, 21, 49–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hajji, H.; Rehali, M.; Taybi, A.F.; Lumaret, J.-P.; Mabrouki, Y. Dung Beetles, Dung Burial, and Plant Growth: Four Scarabaeoid Species and Sorghum. Insects 2024, 15, 1002. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects15121002

Hajji H, Rehali M, Taybi AF, Lumaret J-P, Mabrouki Y. Dung Beetles, Dung Burial, and Plant Growth: Four Scarabaeoid Species and Sorghum. Insects. 2024; 15(12):1002. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects15121002

Chicago/Turabian StyleHajji, Hasnae, Mariyem Rehali, Abdelkhaleq Fouzi Taybi, Jean-Pierre Lumaret, and Youness Mabrouki. 2024. "Dung Beetles, Dung Burial, and Plant Growth: Four Scarabaeoid Species and Sorghum" Insects 15, no. 12: 1002. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects15121002

APA StyleHajji, H., Rehali, M., Taybi, A. F., Lumaret, J.-P., & Mabrouki, Y. (2024). Dung Beetles, Dung Burial, and Plant Growth: Four Scarabaeoid Species and Sorghum. Insects, 15(12), 1002. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects15121002