Limited Cross Plant Movement and Non-Crop Preferences Reduce the Efficiency of Honey Bees as Pollinators of Hybrid Carrot Seed Crops

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Visits of A. mellifera to Male-Fertile and Cytoplasmically Male-Sterile Carrot cultivars

2.1.1. Visit Counts

2.1.2. Counts of Pollen in Relation to Flower Type

2.1.3. Collection and Analysis of Pollen from Foraging Bees Returning to the Hive

2.2. Modelling Visits to Carrot Flowers

3. Results

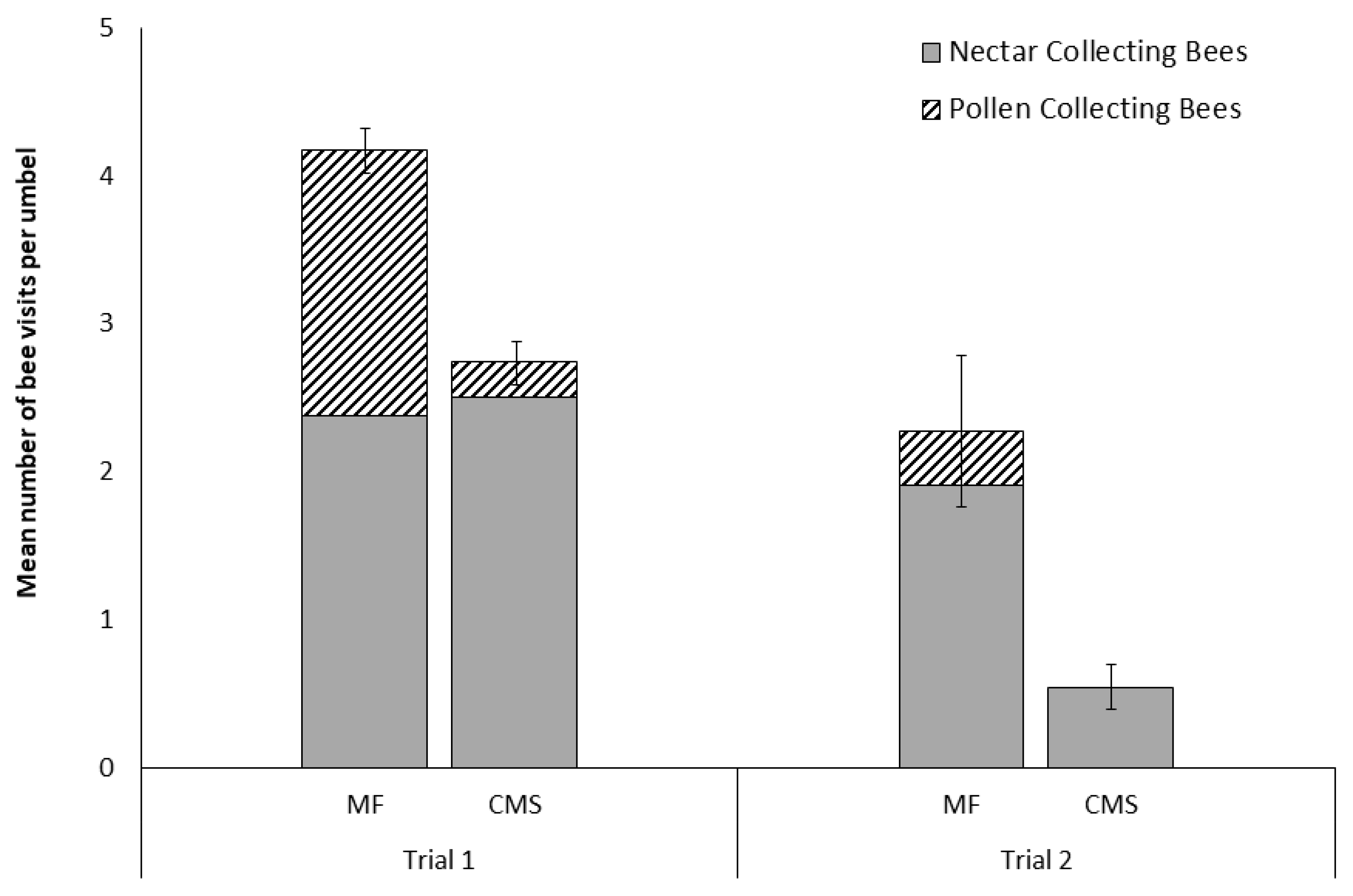

3.1. Visits of A. mellifera to Male-Fertile and Cytoplasmically Male-Sterile Carrot Cultivars

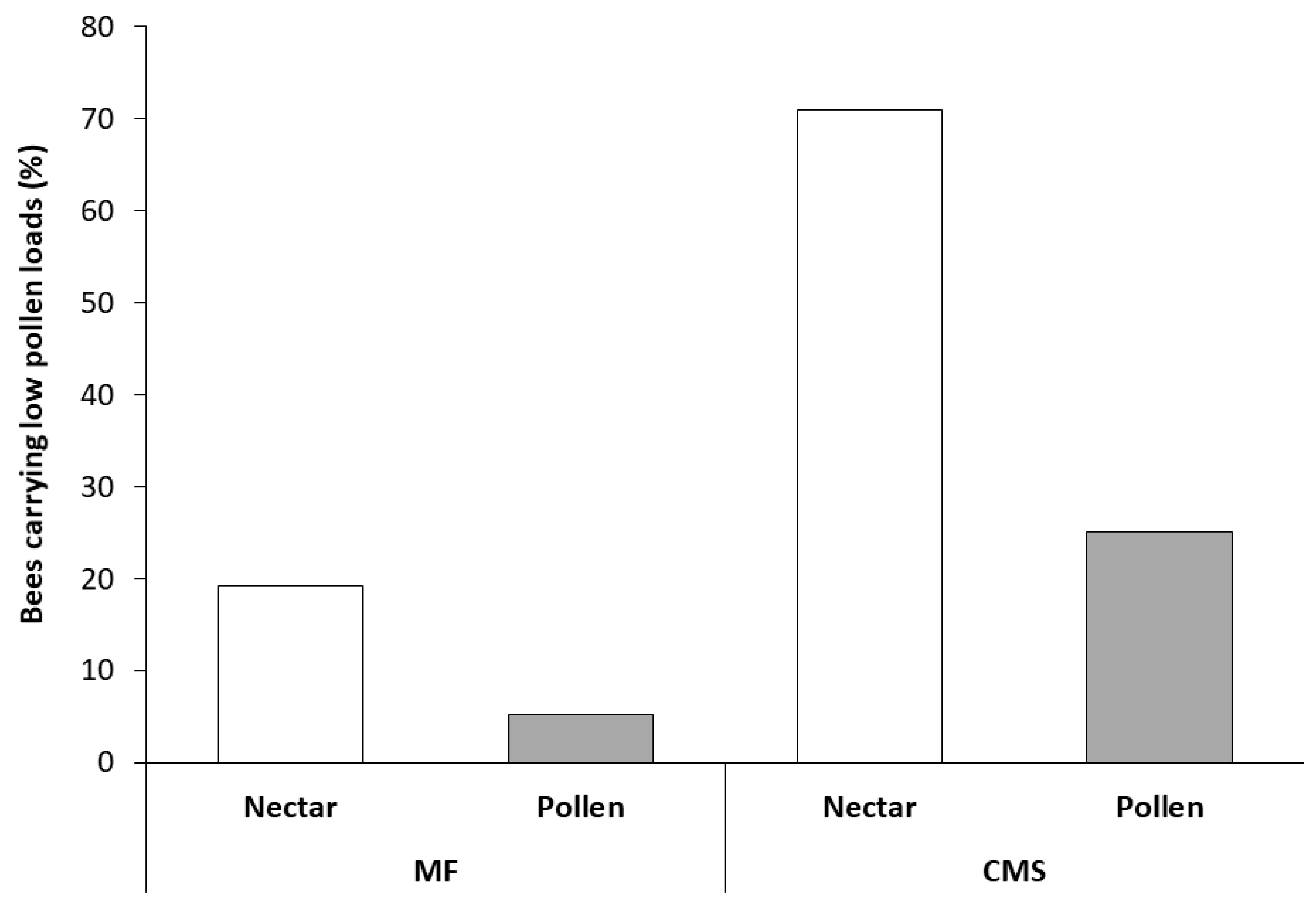

3.2. Collection and Analysis of Pollen from Foraging Bees Returning to the Hive

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rodet, G.; Torre Grossa, J.P.; Bonnet, A. Foraging behavior of Apis mellifera L. on male-sterile and male-fertile inbred lines of carrot (Daucus carota L.) in gridded encolsures. Acta Hortic. 1991, 288, 371–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, R.A.T. Vegetable Seed Production; Antony Rowe Limited: Eastbourne, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Rubatzky, V.E.; Quiros, C.F.; Simon, P.W. Carrots and related vegetable Umbelliferae; CABI Publishing: Wallford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- McGregor, S.E. Chapter 6. Common Vegetables for Seed and Fruit. In Insect Pollination of Cultivated Crop Plants; Agricultural Research Service, US Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Hawthorn, L.R.; Bohart, E.H.; Toole, W.P.; Nye, W.P.; Levin, M.D. Carrot seed production as affected by insect pollination. Bull. Utah Agric. Exp. Stn. 1960, 422, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Erickson, E.H.; Peterson, C.E.; Werner, P. Honey bee foraging and resultant seed set among male-fertile and cytoplasmically male-sterile carrot inbreds and hybrid seed parents. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 1979, 104, 635–638. [Google Scholar]

- Galuszka, H.; Tegrek, K. Honeybee (Apis mellifera L.) foraging in seed plantations of hybrid carrot (Daucus carota L.). In Proceedings of the XXXIst International Congress of Apiculture, Warsaw, Poland, 19–25 August 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Howlett, B.G. Hybrid carrot seed crop pollination by the fly Calliphora vicina (Diptera: Calliphoridae). J. Appl. Entomol. 2012, 136, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howlett, B.G.; Lankin-Vega, G.O.; Pattemore, D.E. Native and introduced bee abundances on carrot seed crops in New Zealand. N. Z. Plant Prot. 2015, 68, 373–379. [Google Scholar]

- Garibaldi, L.A.; Steffan-Dewenter, I.; Winfree, R.; Aizen, M.A.; Bommarco, R.; Cunningham, S.A.; Kremen, C.; Carvalheiro, L.G.; Harder, L.D.; Afik, O.; et al. Wild pollinators enhance fruit set of crops regardless of honey bee abundance. Science 2013, 339, 1608–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaffney, A.; Allen, G.R.; Brown, P.H. Insect visitation to flowering hybrid carrot seed crops. N. Z. J. Crop Hortic. Sci. 2011, 39, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaffney, A.; Bohman, B.; Quarrell, S.R.; Brown, P.H.; Allen, G.R. Frequent insect visitors are not always pollen carriers in hybrid carrot pollination. Insects 2018, 9, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaplane, K.S.; Mayer, D.F. Crop Pollination by Bees; CABI Publishing; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham, S.A.; Fournier, A.; Neave, M.J.; Le Feuvre, D. Improving spatial arrangement of honeybee colonies to avoid pollination shortfall and depressed fruit set. J. Appl. Ecol. 2016, 53, 350–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, H.; Wells, P.H. Optimal diet, minimal uncertainty and individual constancy in the foraging of honey bees, Apis mellifer. J. Anim. Ecol. 1986, 55, 881–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, P.S.M.; Wells, P.H.; Wells, H. Spontaneous flower constancy and learning in honey bees as a function of colour. Anim. Behav. 1997, 54, 615–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visscher, P.K.; Seeley, T.D. Foraging strategy of honeybee colonies in a temperate deciduous forest. Ecology 1982, 63, 1790–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimou, M.; Tananaki, C.; Liolios, V.; Thrasyvoulou, A. Pollen foraging by honey bees (Apis mellifera L.) in Greece: Botanical and geographical origin. J. Apic. Sci. 2014, 58, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, P.; Bryant, V.; Rangel, J. Determining the minimum number of pollen grains needed for accurate honey bee (Apis mellifera) colony pollen pellet analysis. Palynology 2018, 42, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida-Muradian, L.B.; Pamplona, L.C.; Coimbra, S.; Barth, O.M. Chemical composition and botanical evaluation of dried bee pollen pellets. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2005, 18, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, M. Pollination of Crops in Australia and New Zealand; Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation (RIRDC): Ruakura, New Zealand, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Winston, M.L. The Biology of the Honey Bee; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Weidenmüller, A.; Tautz, J. In-hive behavior of pollen foragers (Apis mellifera) in honey bee colonies under conditions of high and low pollen need. Ethology 2002, 108, 205–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thom, C.; Seeley, T.D.; Tautza, J. A scientific note on the dynamics of labor devoted to nectar foraging in a honey bee colony: Number of foragers versus individual foraging activity. Apidologie 2000, 31, 737–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson, E.H.; Peterson, C.E. Asynchrony of floral events and other differences in pollinator foraging stimuli between fertile and male-sterile carrot inbreds. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 1979, 104, 639–643. [Google Scholar]

- Free, J.B. Effect of flower shape and nectar guides on the behaviour of foraging honeybees. Behaviour 1970, 37, 269–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohart, G.E.; Nye, W.P. Insect pollinators of carrots in Utah. Bull. Utah State Univ. Agric. Exp. Stn. 1960, 419, 416. [Google Scholar]

- Macgillivray, D. A centrifuging method for the removal of insect pollen loads. J. Entomol. Soc. S. Afr. 1987, 50, 522–523. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, L.A. On partitioning χ2 and detecting partial association in three-way contingency tables. J. R. Stat. Soc. 1969, 31, 486–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, T.C.; Thorp, R.W.; Briggs, D.; Skinner, J.; Parisian, T. Effects of Pollen Traps on Honey Bee (Hymenoptera: Apidae) Foraging and Brood Rearing During Almond and Prune Pollination. Environ. Entomol. 1985, 14, 683–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spurr, C. Identification and Management of Factors Limiting Hybrid Carrot Seed Production in Australia. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Agricultural Science, University of Tasmania, Hobart, Australia, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ish-Am, G.; Eisikowitch, D. Low attractiveness of avocado (Persea americana Mill.) flowers to honeybees (Apis mellifera L.) limits fruit set in Israel. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 1998, 73, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohart, G.E. Pollination of alfalfa and red clover. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1957, 2, 355–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nye, W.P.; Waller, G.D.; Waters, N.D. Factors affecting pollination of onions in Idaho during 1969. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 1971, 96, 330–332. [Google Scholar]

- Currah, L.; Ockendon, D.J. Pollination activity by blowflies and honeybees on onions in breeders’ cages. Ann. Appl. Biol. 1984, 105, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrol, D.P. Impact of insect pollination on carrot seed production. Insect Environ. 1997, 3, 61. [Google Scholar]

- Vicens, N.; Bosch, J. Weather-dependent pollinator activity in an apple orchard, with special reference to Osmia cornuta and Apis mellifera (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae and Apidae). Environ. Entomol. 2000, 29, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, D.; Robert, D. Predictive modelling of honey bee foraging activity using local weather conditions. Apidologie 2018, 49, 386–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, M.D.; Bohart, E.H. Selection of pollens by honey bees. Am. Bee J. 1955, 95, 392–393. [Google Scholar]

- Pernal, S.F.; Currie, R.W. Discrimination and preferences for pollen-based cues by foraging honeybees, Apis mellifera L. Anim. Behav. 2002, 63, 369–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, S.M.; Awmack, C.S.; Murray, D.A.; Williams, I.H. Are honey bees’ foraging preferences affected by pollen amino acid composition? Ecol. Entomol. 2003, 28, 622–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarchin, S.; Dag, A.; Salomon, M.; Hendriksma, H.P.; Shafir, S. Honey bees dance faster for pollen that complements colony essential fatty acid deficiency. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2017, 71, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, S.M.; Sandoz, J.C.; Martin, A.P.; Murray, D.A.; Poppy, G.M.; Williams, I.H. Could learning of pollen odours by honey bees (Apis mellifera) play a role in their foraging behaviour? Physiol. Entomol. 2005, 30, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenas, A.; Farina, W.M. Learned olfactory cues affect pollen-foraging preferences in honeybees, Apis mellifera. Anim. Behav. 2012, 83, 1023–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larue, A.A.C.; Raguso, R.A.; Junker, R.R. Experimental manipulation of floral scent bouquets restructures flower-visitor interactions in the field. J. Anim. Ecol. 2016, 85, 396–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broussard, M.A.; Mas, F.; Howlett, B.; Pattemore, D.; Tylianakis, J.M. Possible mechanisms of pollination failure in hybrid carrot seed and implications for industry in a changing climate. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0180215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mas, F.; Harper, A.; Horner, R.; Welsh, T.; Jaksons, P.; Suckling, D.M. The importance of key floral bioactive compounds to honey bees for the detection and attraction of hybrid vegetable crops and increased seed yield. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 98, 4445–4453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Collection Date | Time | Total Weight (g) | 100-Ball Weight (g) | Est. Pollen Balls # | Pollen Balls/day | Tmin (°C) | Tmax (°C) | Rain (mm) | Evaporation (mm) | Bright Sunshine (h) | Crop in Flower (%) ⬧ | Carrot Pollen (%) * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 06 Jan | 12:00 | 7.81 | 0.67 | 1175 | 2431 | 7.4 | 25.5 | 0 | 5.8 | 12.6 | 32 | 1.7 |

| 06 Jan | 17:30 | 10.04 | 0.80 | 1256 | 0 | |||||||

| 12 Jan | 12:00 | 7.67 | 0.68 | 1125 | 1591 | 8.6 | 20.4 | 0 | 8.0 | 12.6 | 40 | 3.3 |

| 12 Jan | 21:30 | 3.66 | 0.78 | 466 | 6.7 | |||||||

| 15 Jan | 12:00 | 6.94 | 0.68 | 1016 | 1286 | 12.5 | 24.9 | 0 | 9.6 | 9.7 | 49 | 3.3 |

| 15 Jan | 21:00 | 2.21 | 0.82 | 270 | 1.7 | |||||||

| 19 Jan | 12:00 | 4.40 | 0.64 | 690 | 1112 | 5.1 | 24.8 | 0 | 4.8 | 13.5 | 58 | 1.7 |

| 19 Jan | 21:00 | 2.91 | 0.69 | 422 | 1.7 | |||||||

| 23 Jan | 12:00 | 6.38 | 0.55 | 1160 | 1819 | 11.4 | 22.2 | 0 | 8.0 | 11.3 | 59 | 3.3 |

| 23 Jan | 21:00 | 3.85 | 0.58 | 660 | 3.3 | |||||||

| 04 Feb | 12:00 | 33.75 | 0.78 | 4327 | 5953 | 11.4 | 22.3 | 0 | 3.2 | 10.2 | 76 | 0 |

| 04 Feb | 21:45 | 10.19 | 0.63 | 1626 | 0 | |||||||

| 10 Feb | 12:00 | 14.00 | 0.79 | 1770 | 2588 | 11.7 | 18.2 | 0 | 4.8 | 4 | 87 | 0 |

| 10 Feb | 20:45 | 6.23 | 0.76 | 818 | 1.7 | |||||||

| 13 Feb | 12:00 | 34.87 | 0.76 | 4605 | 5054 | 10.5 | 23.4 | 0 | 5.6 | 8.5 | 80 | 0 |

| 13 Feb | 20:45 | 2.52 | 0.56 | 449 | 3.3 | |||||||

| 16 Feb | 12:35 | 33.49 | 0.82 | 4109 | 5288 | 10 | 20.7 | 0 | 4.2 | 12.4 | 73 | 0 |

| 16 Feb | 21:00 | 8.29 | 0.70 | 1180 | 0 | |||||||

| 20 Feb | 21:00 | 5.57 | 0.79 | 702 | 702 | 10.3 | 24.9 | 2.8 | 5.8 | 7.1 | 62 | 0 |

| 24 Feb | 21:30 | 8.36 | 0.79 | 1062 | 1062 | 4.1 | 18.8 | 0 | 5.4 | 11.3 | 52 | 0 |

| 27 Feb | 12:00 | 12.56 | 0.76 | 1650 | 2656 | 13.9 | 23.3 | 0 | 5.8 | 6.9 | 57 | 0 |

| 27 Feb | 20:00 | 8.79 | 0.87 | 1005 | 0 | |||||||

| 01 Mar | 12:30 | 2.61 | 0.70 | 374 | NA | 9.5 | 17.7 | 1.4 | 2.2 | 4.4 | 60 | 0 |

| Plant type | Family | Distance (km) | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chenopodium alba, fat hen | Chenopodiaceae | 0 | Frequent |

| Hypochoeris radicata, cats ear | Asteraceae | 0 | Frequent |

| Malva sp., mallow | Malvaceae | 0 | Frequent |

| Trifolium sp., clover | Fabaceae | 0 | Frequent |

| Plantago lanceolata, plantain | Plantaginaceae | 0 | Frequent |

| Raphanus raphanistrum, wild radish | Brassicaceae | 0 | Frequent |

| Taraxacum sp., dandelion | Asteraceae | 0 | Infrequent |

| Gazania sp. | Asteraceae | 0.5 | Frequent |

| Onopordum sp., thistle | Asteraceae | 0.5 | Infrequent |

| Rosa rubiginosa, sweet briar | Rosaceae | 0.5 | very frequent |

| Rosa sp., rose | Rosaceae | 0.5 | single plant |

| Rubus fruticosus, blackberry | Rosaceae | 0.5 | single plant |

| Bursaria spinosa, prickly box | Pittosporaceae | 2.2 | Frequent |

| Cassinia sp. | Asteraceae | 2.2 | Frequent |

| Eucalyptus sp. | Myrtaceae | 2.2 | Frequent |

| Ozothamnus sp. | Asteraceae | 2.2 | Frequent |

| Asteraceae sp., daisy | Asteraceae | 2.7 | Infrequent |

| Lobularia maritimus, sweet alyssum | Brassicaceae | 2.7 | Infrequent |

| Pelargonium sp. | Geraniaceae | 2.7 | Infrequent |

| Tropaeolum majus, nasturtium, | Tropaeolaceae | 2.7 | Frequent |

| Acacia mearnsii, black wattle | Fabaceae | 0.5–2.3 | Frequent |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gaffney, A.; Bohman, B.; Quarrell, S.R.; Brown, P.H.; Allen, G.R. Limited Cross Plant Movement and Non-Crop Preferences Reduce the Efficiency of Honey Bees as Pollinators of Hybrid Carrot Seed Crops. Insects 2019, 10, 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects10020034

Gaffney A, Bohman B, Quarrell SR, Brown PH, Allen GR. Limited Cross Plant Movement and Non-Crop Preferences Reduce the Efficiency of Honey Bees as Pollinators of Hybrid Carrot Seed Crops. Insects. 2019; 10(2):34. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects10020034

Chicago/Turabian StyleGaffney, Ann, Björn Bohman, Stephen R. Quarrell, Philip H. Brown, and Geoff R. Allen. 2019. "Limited Cross Plant Movement and Non-Crop Preferences Reduce the Efficiency of Honey Bees as Pollinators of Hybrid Carrot Seed Crops" Insects 10, no. 2: 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects10020034

APA StyleGaffney, A., Bohman, B., Quarrell, S. R., Brown, P. H., & Allen, G. R. (2019). Limited Cross Plant Movement and Non-Crop Preferences Reduce the Efficiency of Honey Bees as Pollinators of Hybrid Carrot Seed Crops. Insects, 10(2), 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects10020034