Identification and Evaluation of Tool Tip Contact and Cutting State Using AE Sensing in Ultra-Precision Micro Lathes †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

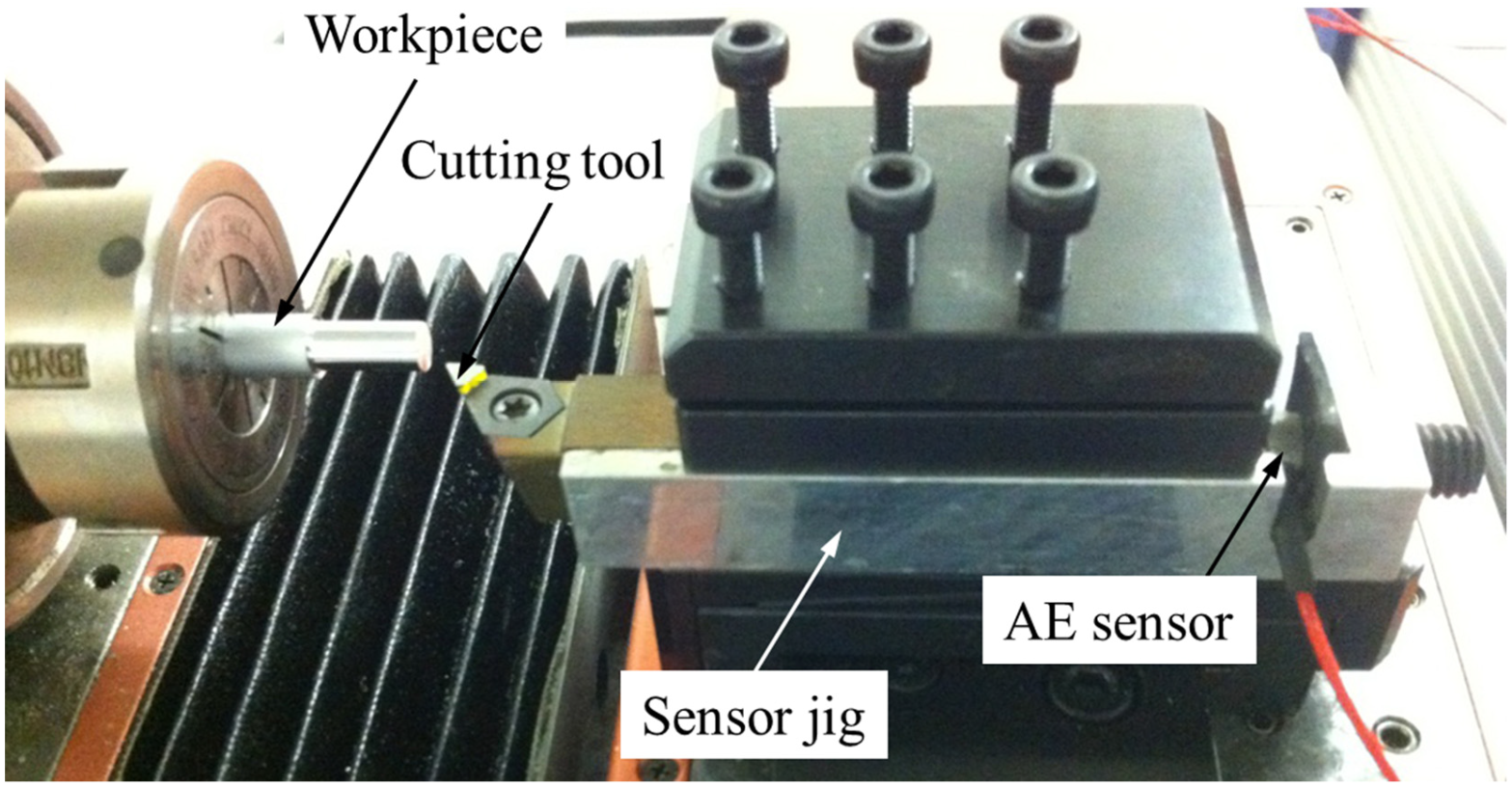

2.1. Cutting Experiments on an Ultra-Precision Micro Lathe

2.2. Cutting Simulations via the Finite Element Method

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Change in the AE Signal Waveform Detected from the Contact of the Cutting Tool and the Workpiece Until the Workpiece Was Cut

3.2. Detection of the AE Signal at Contact of the Cutting Tool and the Workpiece

3.3. Effect of the Spindle Rotating Speed and the Cutting Depth on the AE Signals

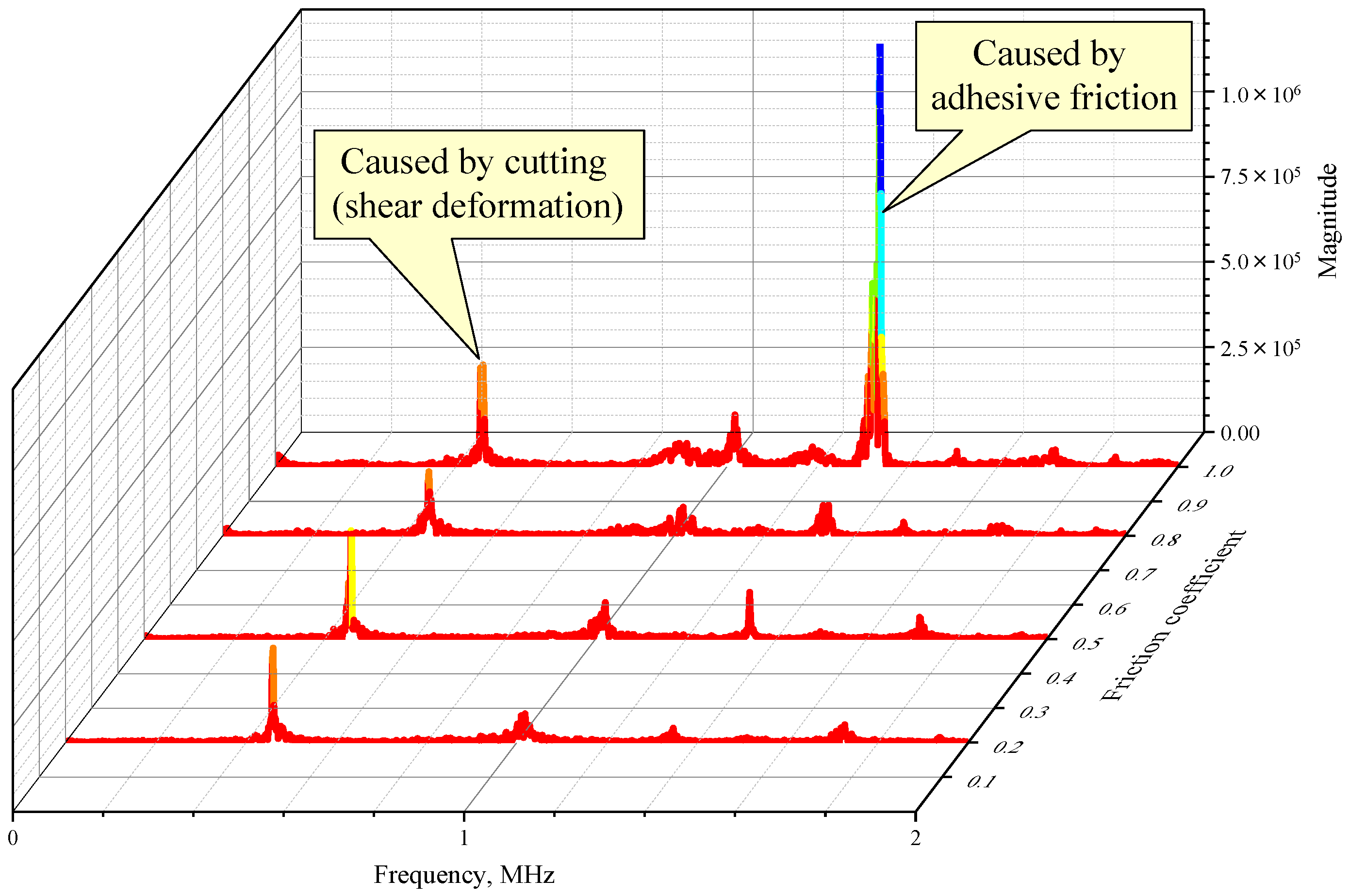

3.4. Identification of the Cutting State by the AE Frequency Spectrum

3.5. Verification of AE Frequency Changes Using Finite Element Analysis

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- The amplitude of the AE signal waveform changed stepwise during the following cutting processes: contact between the cutting tool and the workpiece, elastoplastic deformation of the workpiece, and formation of chips (shear deformation).

- (2)

- AE sensing can detect contact between the cutting tool and the workpiece with a high precision of 0.1 μm.

- (3)

- The amplitude of the AE signal waveform increases with increasing spindle rotation speed and increasing cutting depth, except in the case of abnormal cutting, such as when the workpiece material adheres to the cutting tool.

- (4)

- The AE frequency spectrum feature for each cutting process is as follows: a frequency peak occurs at ~0.2 MHz during the cutting process, and frequency peaks are observed above 1 MHz during adhesion of the workpiece material.

- (5)

- Adhesion of the workpiece material to the rake face of the cutting tool (i.e., the formation of a built-up edge) can be identified by detecting high-frequency (>1 MHz) AE signals.

- (6)

- FEA revealed that the strain-rate variations in the shear zone and on the tool rake face influence the AE waves generated during cutting.

- (7)

- The frequency spectrum of cutting forces obtained via FEA under high-friction conditions was found to be similar to the frequency spectrum of AE signals recorded during adhesion in cutting experiments.

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AE | Acoustic Emission |

| EV | Electric Vehicle |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| CNC | Computer Numerical Control |

| CAGR | Compound Annual Growth Rate |

| PZT | Lead Zirconate Titanate |

| JIS | Japanese Industrial Standards |

| FEA | Finite Element Analysis |

| FEM | Finite Element Method |

References

- Järvenpää, E.; Heikkilä, R.; Tuokko, R. TUT-microfactory—A small-size, modular and sustainable production system. In Proceedings of the 11th Global Conference on Sustainable Manufacturing, Berlin, Germany, 23–25 September 2013; pp. 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okazaki, Y. Microfactories: A new methodology for sustainable manufacturing. Int. J. Autom. Technol. 2010, 4, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashida, K. On-demand MEMS device production system by module-based microfactory. Int. J. Autom. Technol. 2010, 4, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S. Desktop CNC Machines Market; MRFR/IA-E/6134-HCR; Market Research Future: New York, NY, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, Q.; Zhang, X.; Wang, S.; Yu, X.; Liu, Q.; Liu, T. Milling Tool Wear Monitoring via the Multichannel Cutting Force Coefficients. Machines 2024, 12, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, E.; Jáuregui-Correa, J.C. Time–Frequency Approach for Cutting Tool Power Signal Separation in Face Milling Operations. Appl. Mech. 2024, 5, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, R.; Araújo, A. The Deterministic Nature of Sensor-Based Information for Condition Monitoring of the Cutting Process. Machines 2021, 9, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denkena, B.; Bergmann, B.; Stiehl, T.H. Transfer of Process References between Machine Tools for Online Tool Condition Monitoring. Machines 2021, 9, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheffer, C.; Heyns, P.S. Wear monitoring in turning operations using vibration and strain measurements. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2001, 15, 1185–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.H.; Kim, H.J.; Nam, J.H.; Lee, S.H. Ductile–Brittle Mode Classification for Micro-End Milling of Nano-FTO Thin Film Using AE Monitoring and CNN. Coatings 2025, 15, 933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sender, P.; Buj-Corral, I.; Álvarez-Flórez, J. Analysis of Roughness, the Material Removal Rate, and the Acoustic Emission Signal Obtained in Flat Grinding Processes. Machines 2024, 12, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maia, L.H.A.; Abrão, A.M.; Vasconcelos, W.L.; Júnior, J.L.; Fernandes, G.H.N.; Machado, Á.R. Enhancing Machining Efficiency: Real-Time Monitoring of Tool Wear with Acoustic Emission and STFT Techniques. Lubricants 2024, 12, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudzik, K.; Labuda, W. The Possibility of Applying Acoustic Emission and Dynamometric Methods for Monitoring the Turning Process. Materials 2020, 13, 2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sio-Sever, A.; Leal-Muñoz, E.; Lopez-Navarro, J.M.; Alzugaray-Franz, R.; Vizan-Idoipe, A.; de Arcas-Castro, G. Non-Invasive Estimation of Machining Parameters during End-Milling Operations Based on Acoustic Emission. Sensors 2020, 20, 5326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Min, S.; Lidde, J.; Raue, N.; Dornfeld, D. Acoustic emission based tool contact detection for ultra-precision machining. CIRP Ann. Manuf. Technol. 2011, 60, 141–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.E.; Wang, I.; Valente, C.M.O.; Oliveira, J.F.G.; Dornfeld, D.A. Precision manufacturing process monitoring with acoustic emission. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2006, 46, 176–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.B.; Ammula, S.C. Real-time acoustic emission monitoring for surface damage in hard machining. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2005, 45, 1622–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hase, A. Acoustic Emission Signal during Cutting Process on Super-Precision Micro-Machine Tool. In Proceedings of the Global Engineering, Science and Technology Conference, Singapore, 3–4 October 2013; No. 521. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, G.; Tang, A.; Zhang, Z.; Xing, H.; Xu, N.; Duan, R. Finite Element Simulation of Orthogonal Cutting of H13-Hardened Steel to Evaluate the Influence of Coatings on Cutting Temperature. Coatings 2024, 14, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Ge, X.; Qiu, C.; Lei, S. FEM assessment of performance of microhole textured cutting tool in dry machining of Ti-6Al-4V. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2016, 84, 2609–2621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikawa, M.; Mori, H.; Kitagawa, Y.; Okada, M. FEM simulation for orthogonal cutting of Titanium-alloy considering ductile fracture to Johnson-Cook model. Mech. Eng. J. 2016, 3, 15-00536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erturk, A.S.; Larsson, R. Subscale modeling of material flow in orthogonal metal cutting. Int. J. Mater. Form. 2025, 18, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajdu, D.; Astarloa, A.; Kovacs, I.; Dombovari, Z. The curved uncut chip thickness model: A general geometric model for mechanistic cutting force predictions. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2023, 188, 104019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimmel, R.J.; Endres, W.J.; Stevenson, R. Application of an Internally Consistent Material Model to Determine the Effect of Tool Edge Geometry in Orthogonal Machining. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. 2002, 124, 536–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinogradov, A.; Nadtochiy, M.; Hashimoto, S.; Miura, S. Correlation between Spectral Parameters of Acoustic Emission during Plastic Deformation of Cu and Cu–Al Single and Polycrystals. Mater. Trans. 1995, 36, 426–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, M.; Mizuno, M.; Sasada, T. Study on friction wear utilizing acoustic emission: Wear mode and AE spectrum of copper. J. Jpn. Soc. Prec. Eng. 1990, 56, 1474–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwata, T.; Fukuda, M.; Oikawa, M.; Kano, M.; Mihara, Y. Acoustic emission analysis of seizure transition process between steel journals and aluminum alloy plain bearings. Tribol. Int. 2025, 202, 110324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hase, A.; Mishina, H.; Wada, M. Correlation between features of acoustic emission signals and mechanical wear mechanisms. Wear 2012, 292–293, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hase, A.; Wada, M.; Mishina, H. Scanning electron microscope observation study for identification of wear mechanism using acoustic emission technique. Tribol. Int. 2014, 72, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hase, A. In Situ Measurement of the Machining State in Small-Diameter Drilling by Acoustic Emission Sensing. Coatings 2024, 14, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svenningsson, I.; Tatar, K. On the mechanism of three-body adhesive wear in turning. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2021, 113, 3457–3472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, V.F.C.; Silva, F.J.G. Recent Advances on Coated Milling Tool Technology—A Comprehensive Review. Coatings 2020, 10, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koga, T.; Hase, A.; Ninomiya, K.; Okita, K. Acoustic emission technique for contact detection and cutting state monitoring in ultra-precision turning. Mech. Eng. J. 2019, 6, 19-00169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Hao Cui, H.; Wang, Y.; Yang, W.; He, L. Multi-physics analytical modeling of the primary shear zone and milling force prediction. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2023, 316, 117949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, C.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Dong, Y. Physics-guided degradation trajectory modeling for remaining useful life prediction of rolling bearings. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2025, 224, 112192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cutting Tool | Cermet Single-Crystal Diamond |

|---|---|

| Workpiece material | Free-cutting brass Aluminum alloy |

| Spindle rotating speed N, rpm | 500, 1000, 1500, 2000, 3000 |

| Cutting depth d, µm | 100, 10, 1, 0.1 |

| AE amplification factor, dB | 80 |

| AE band-pass filter, MHz | High-pass filter: 0.1 Low-pass filter: THRU |

| Free-Cutting Brass (C3640) | 57.0% to 61.0% Cu, 1.8% to 3.7% Pb, Up to 0.50% Fe, 1.0% Impurities Excluding Fe, Remainder Zn |

|---|---|

| Aluminum alloy (A6063) | Al balance, 0.20% to 0.6% Si, up to 0.35% Fe, up to 0.10% Cu, up to 0.10% Mn, 0.45% to 0.9% Mg, up to 0.10% Cr, up to 0.10% Zn, and up to 0.10% Ti |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hase, A. Identification and Evaluation of Tool Tip Contact and Cutting State Using AE Sensing in Ultra-Precision Micro Lathes. Lubricants 2026, 14, 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants14010007

Hase A. Identification and Evaluation of Tool Tip Contact and Cutting State Using AE Sensing in Ultra-Precision Micro Lathes. Lubricants. 2026; 14(1):7. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants14010007

Chicago/Turabian StyleHase, Alan. 2026. "Identification and Evaluation of Tool Tip Contact and Cutting State Using AE Sensing in Ultra-Precision Micro Lathes" Lubricants 14, no. 1: 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants14010007

APA StyleHase, A. (2026). Identification and Evaluation of Tool Tip Contact and Cutting State Using AE Sensing in Ultra-Precision Micro Lathes. Lubricants, 14(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants14010007