Mechanism of Inner Rail Corrugation on Large-Radius Curves in Metro Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

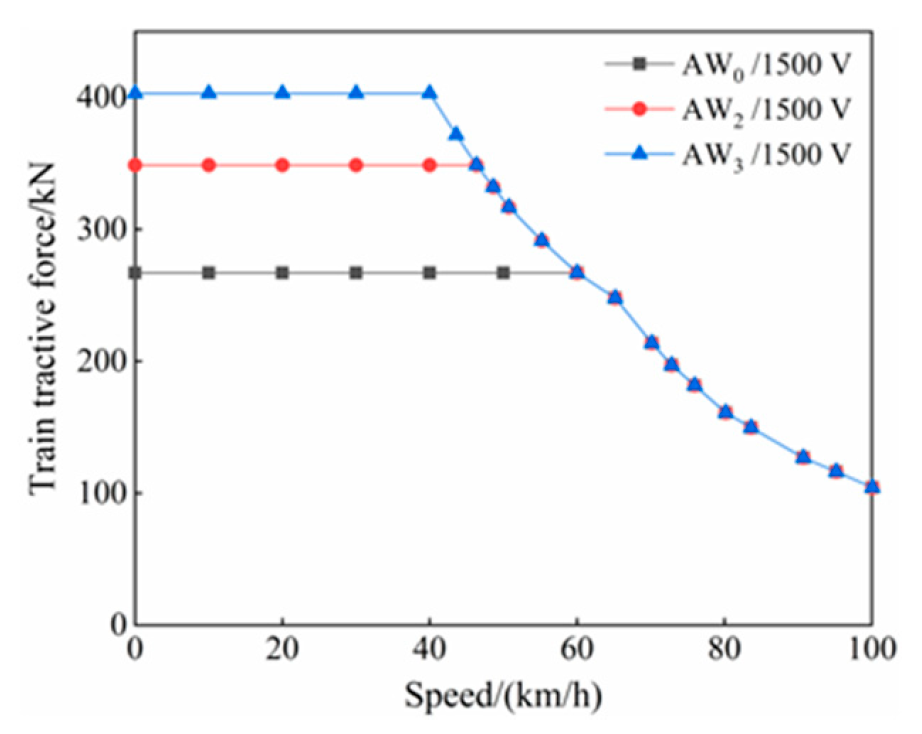

2. Analysis of Wheel–Rail Creep Characteristics on Large-Radius Curves

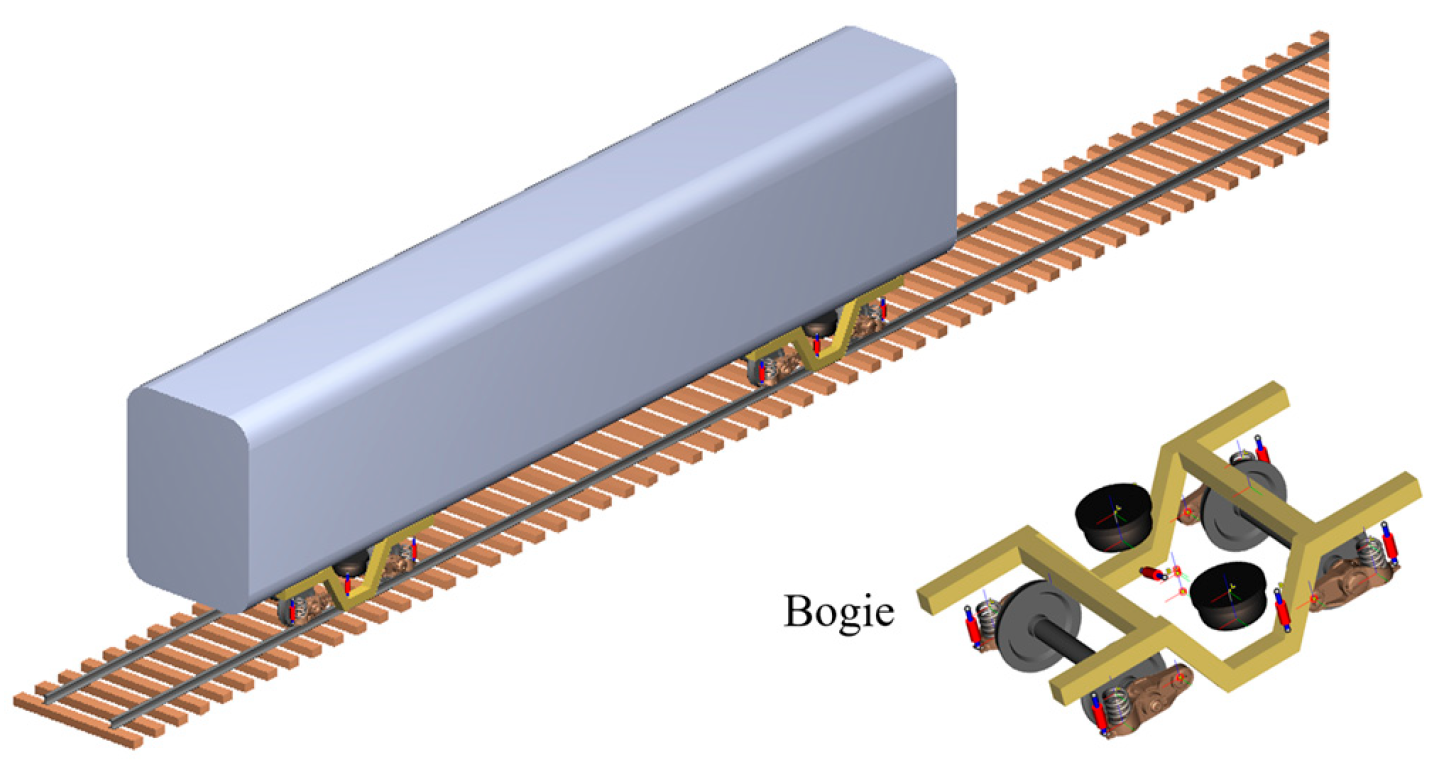

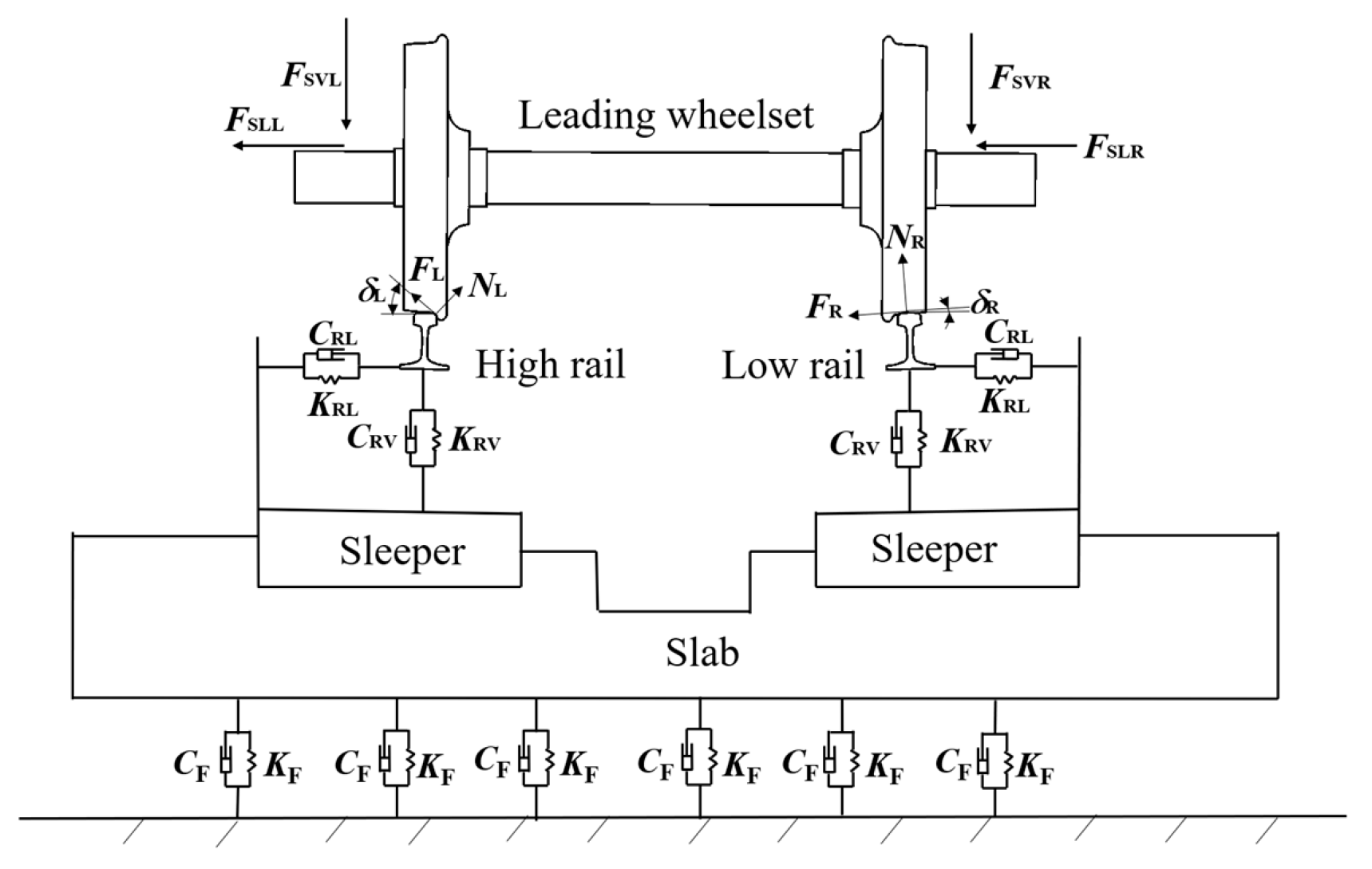

2.1. Development of a Vehicle–Track Dynamic Model

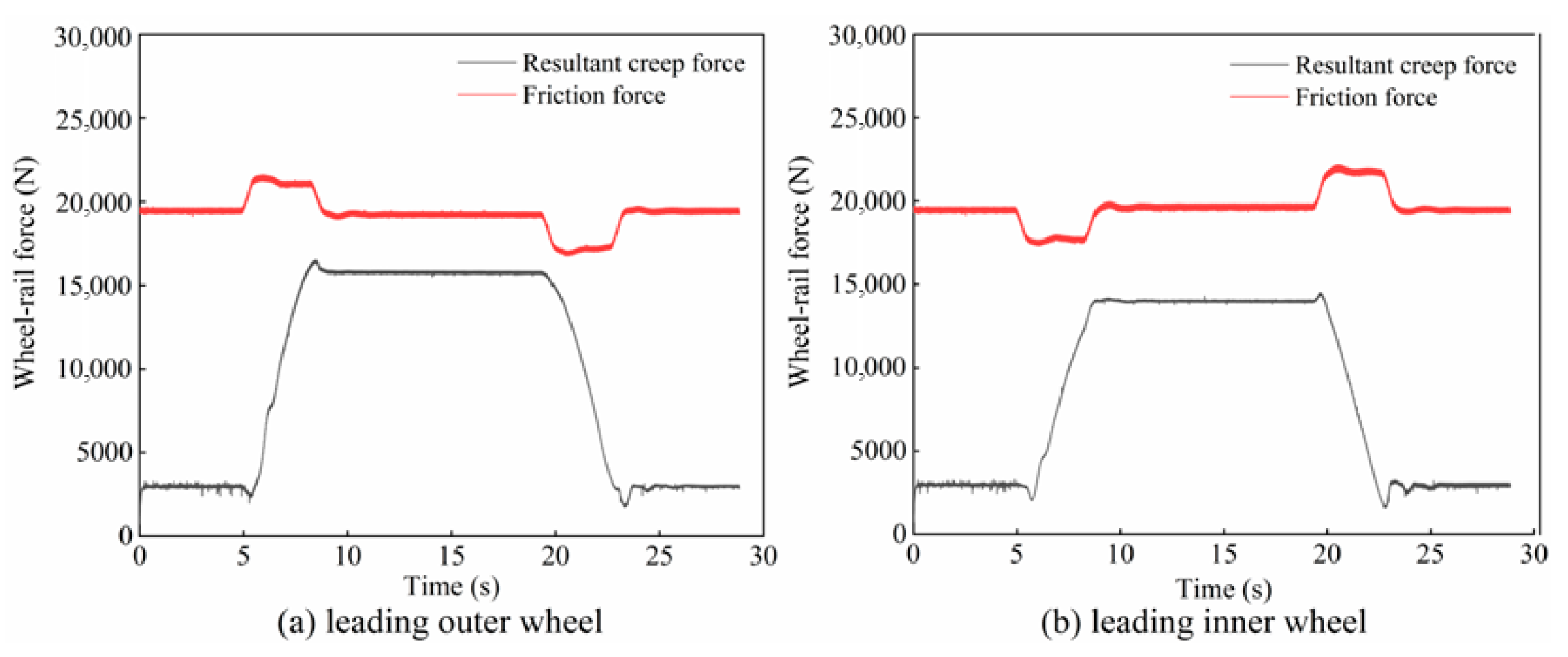

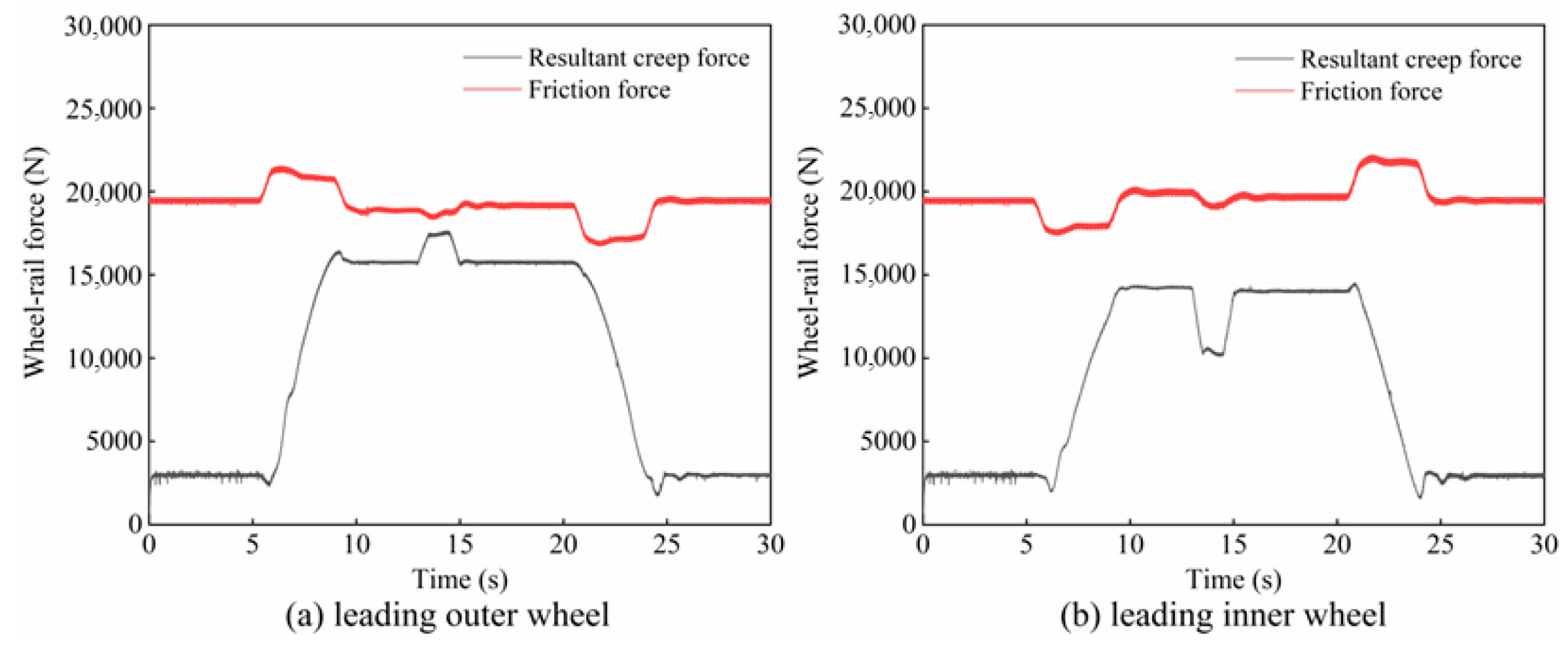

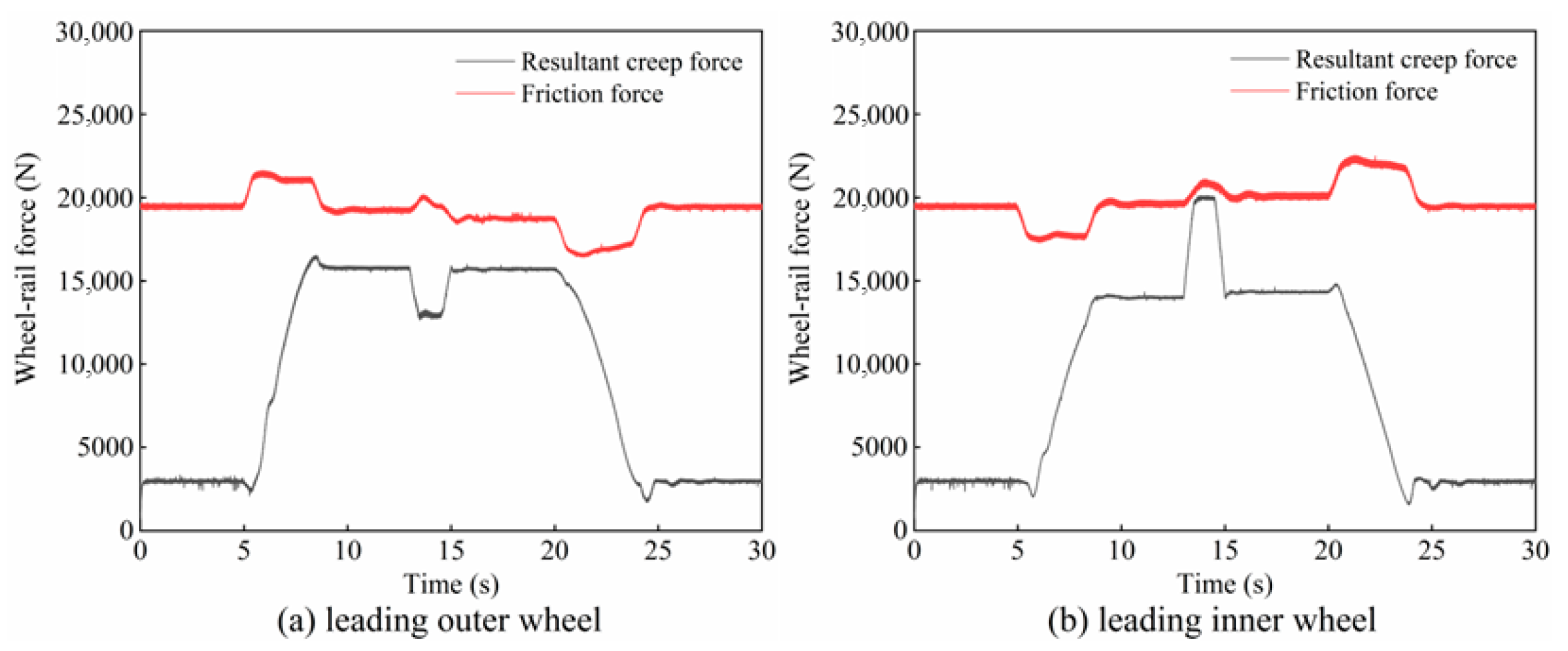

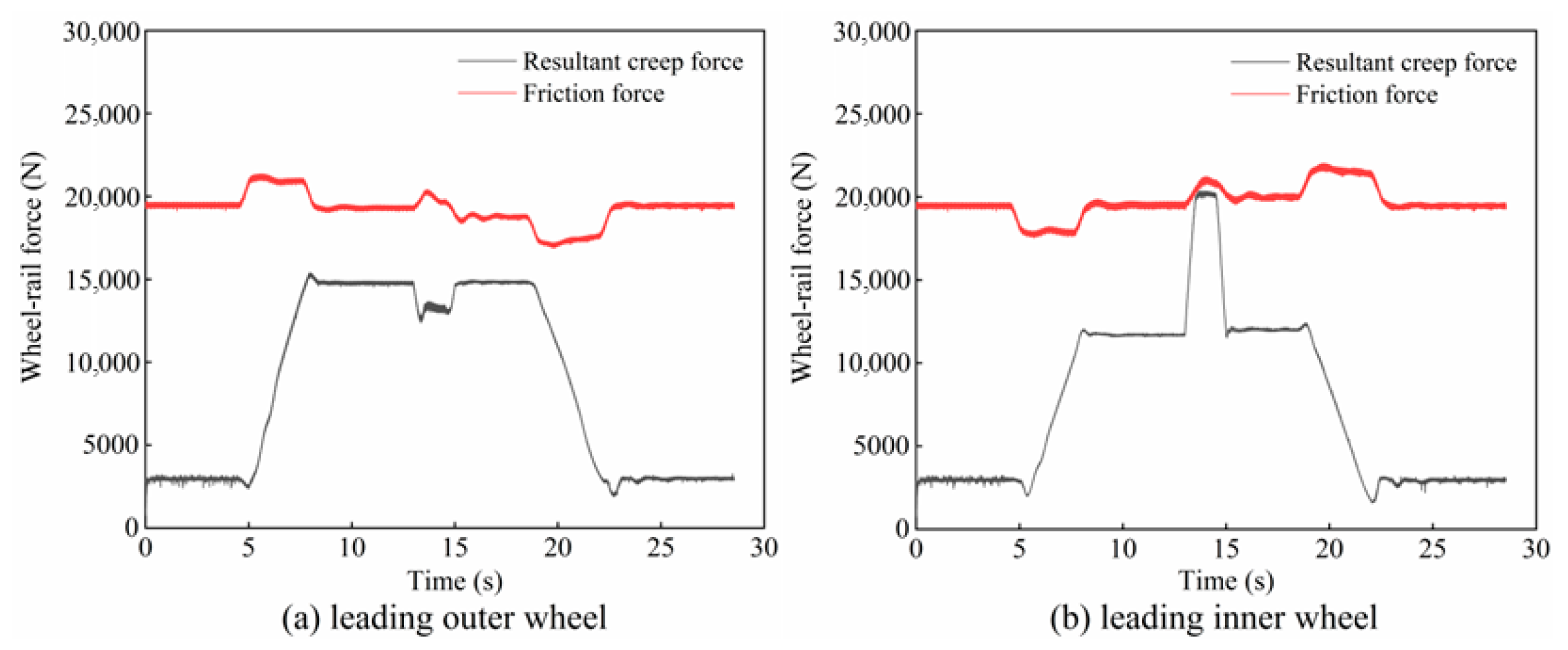

2.2. Creep Characteristics of the Wheel–Rail Interface During Coasting

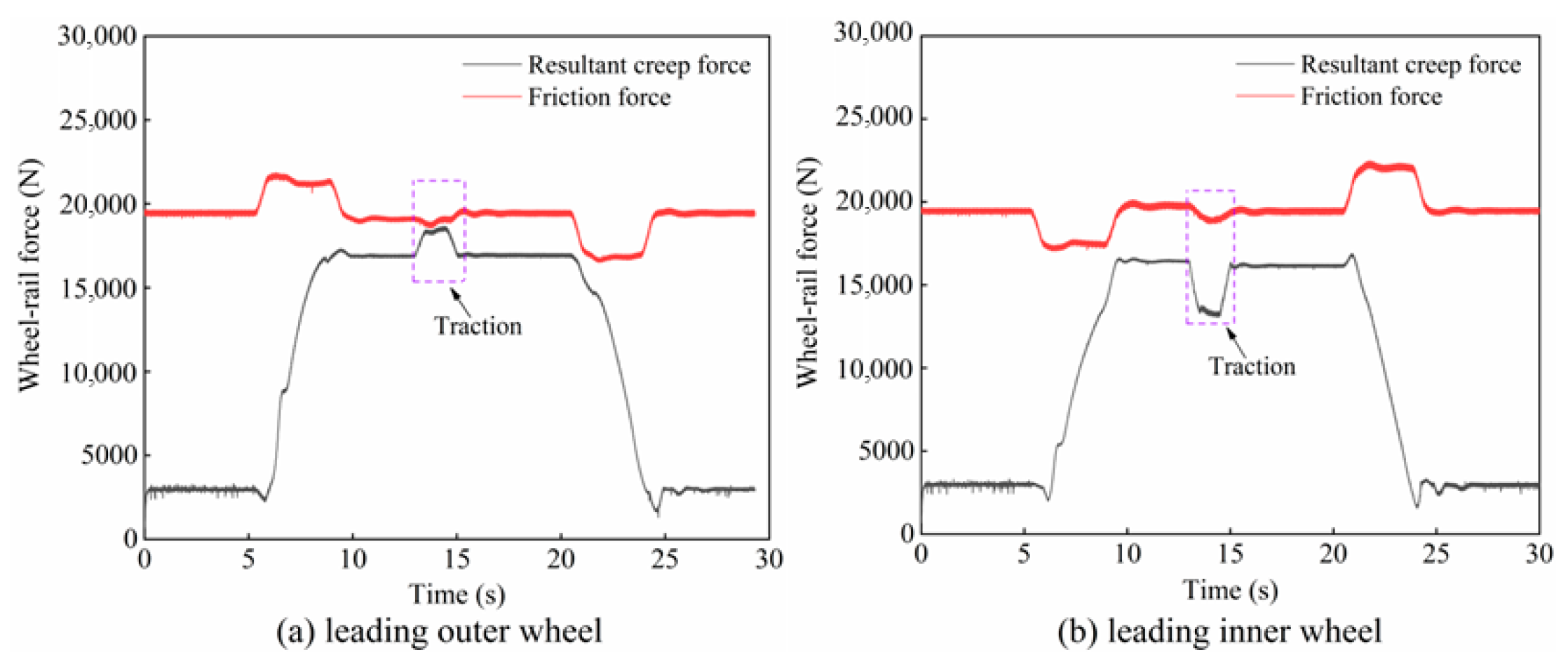

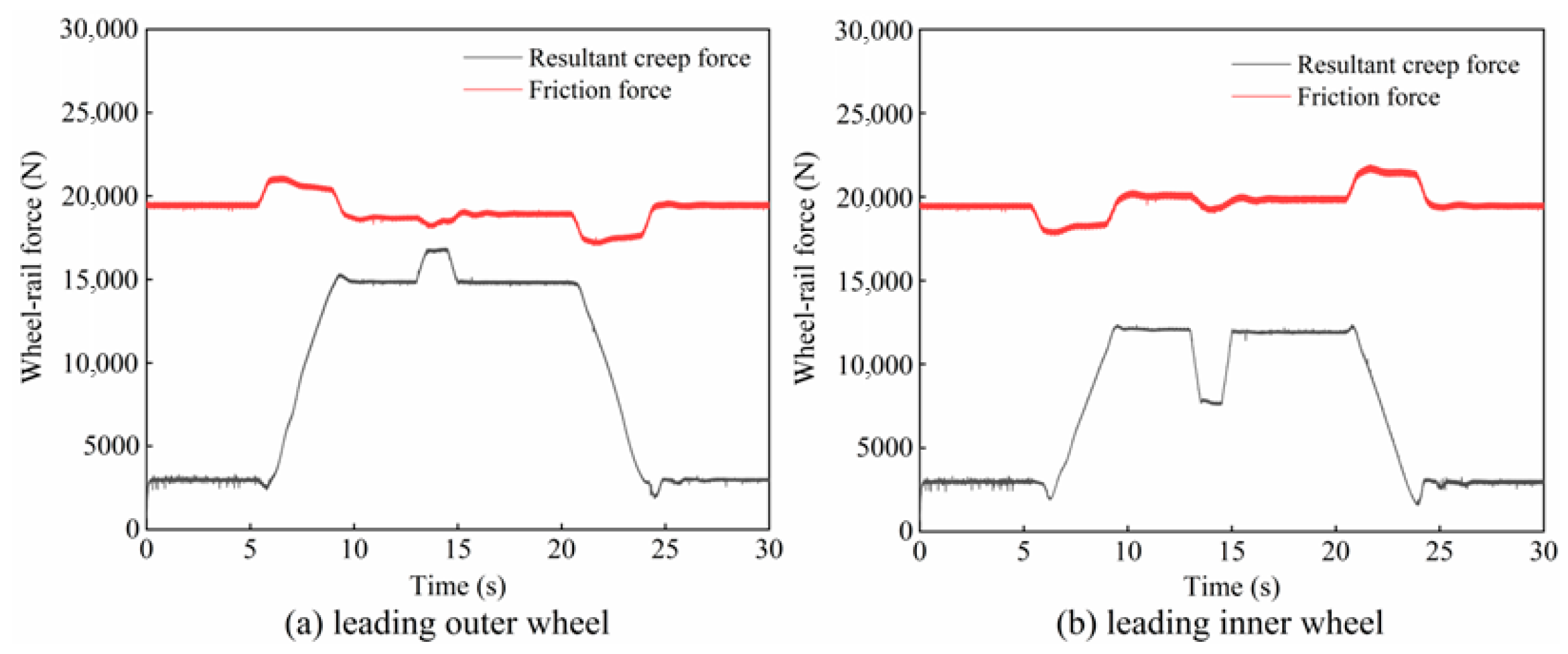

2.3. Creep Characteristics of the Wheel–Rail Interface During Traction

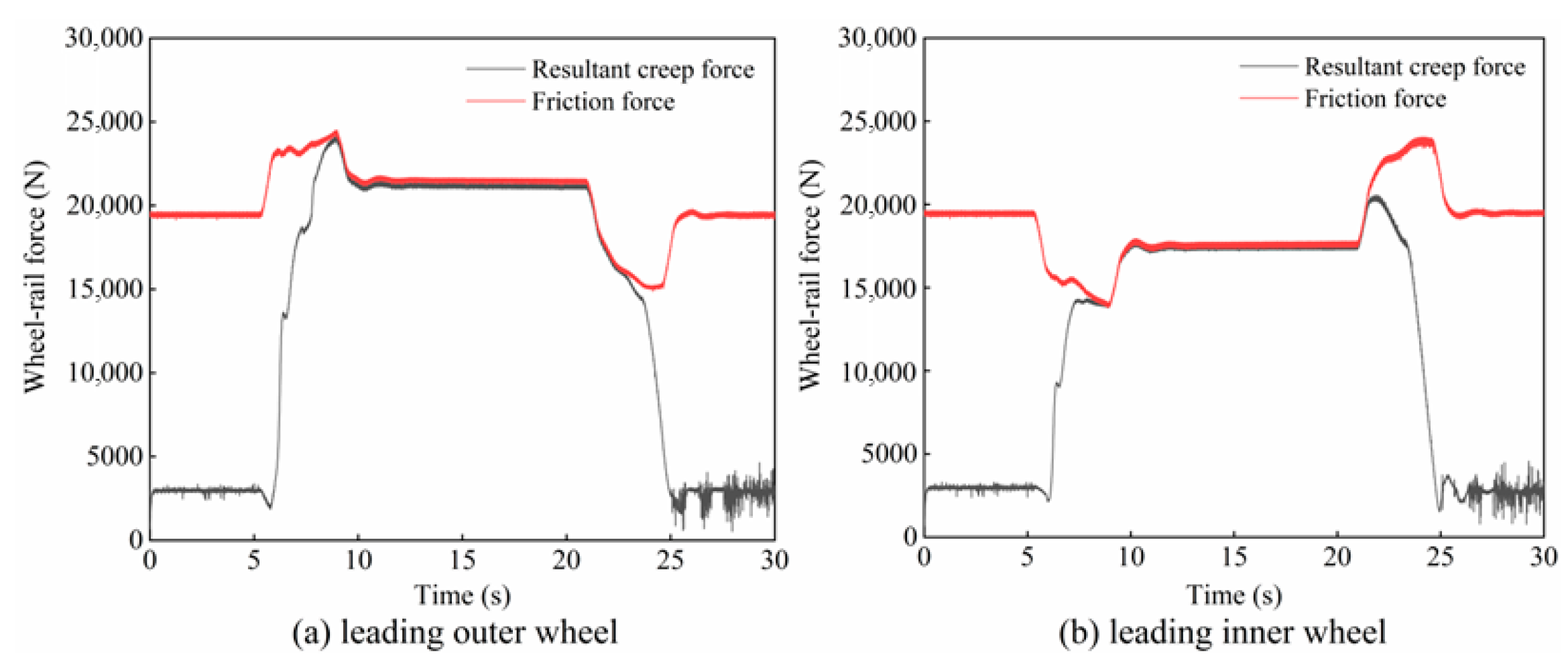

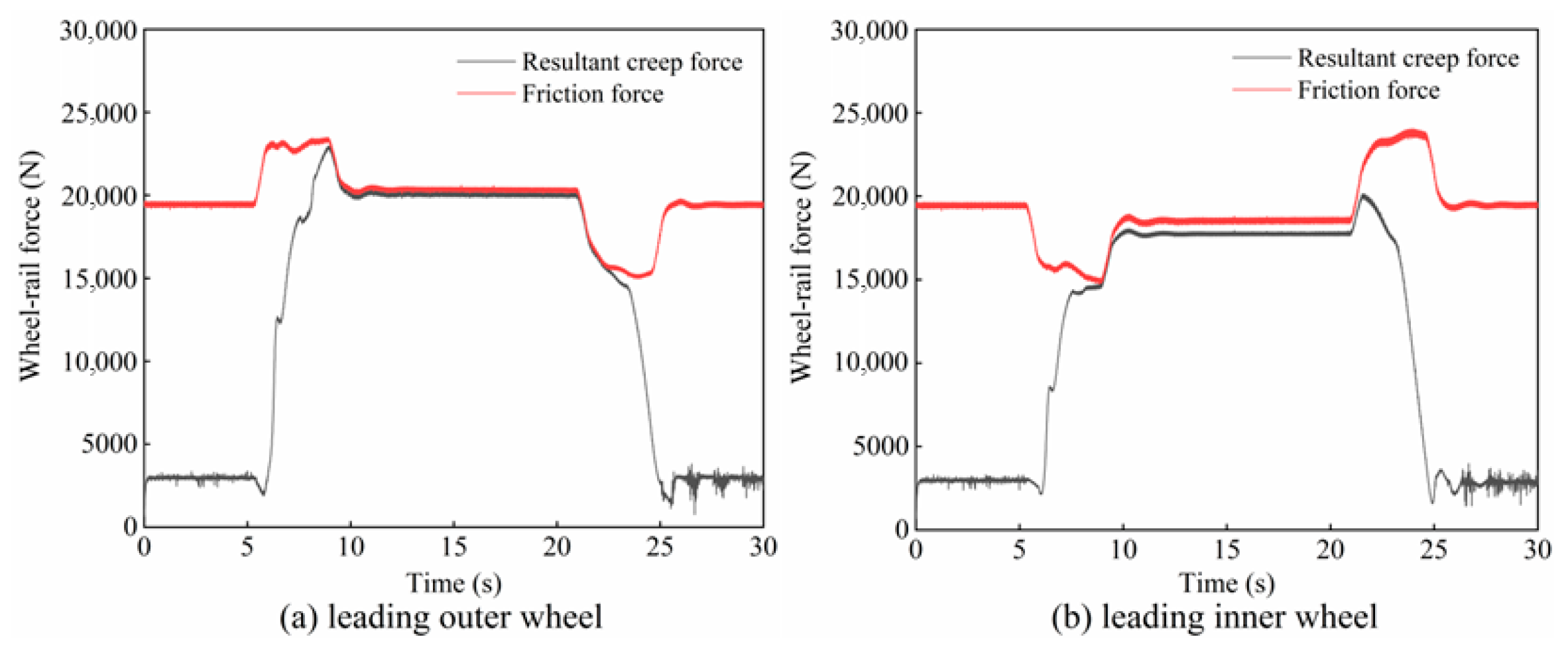

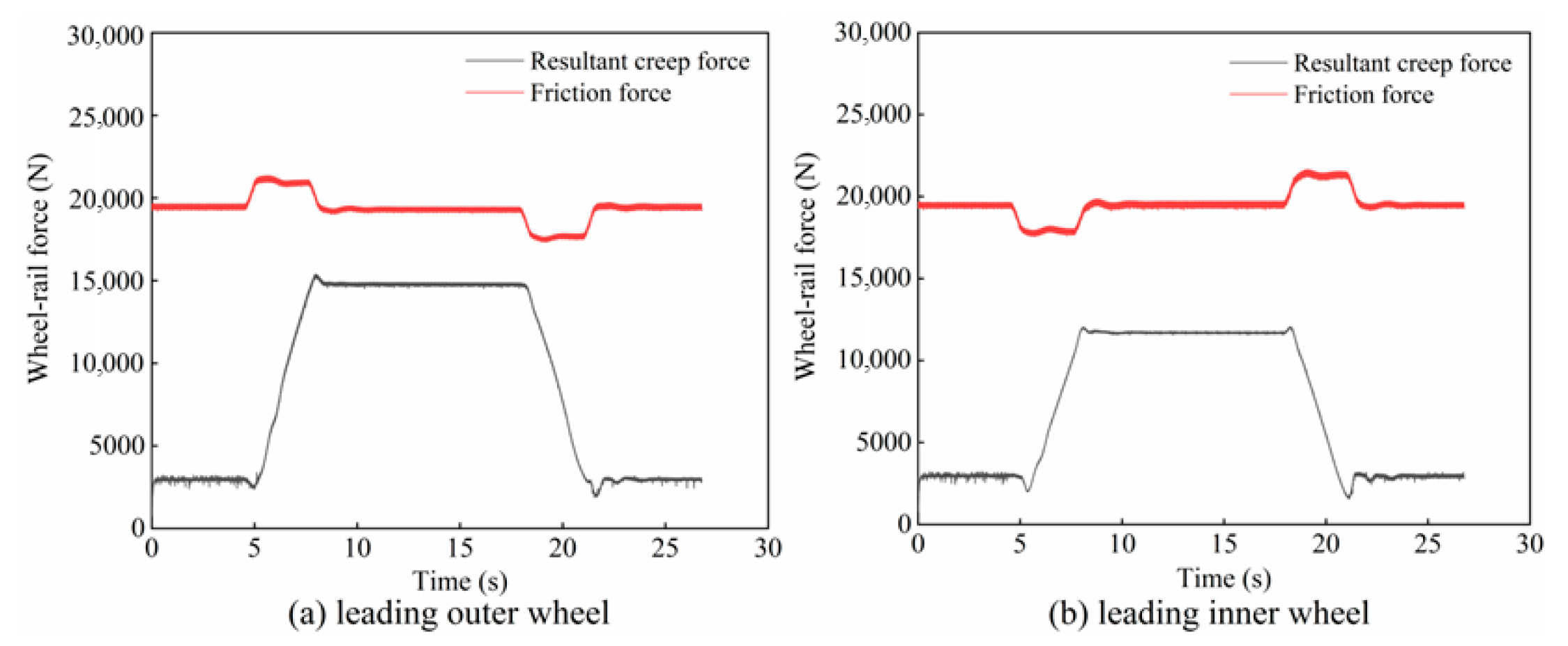

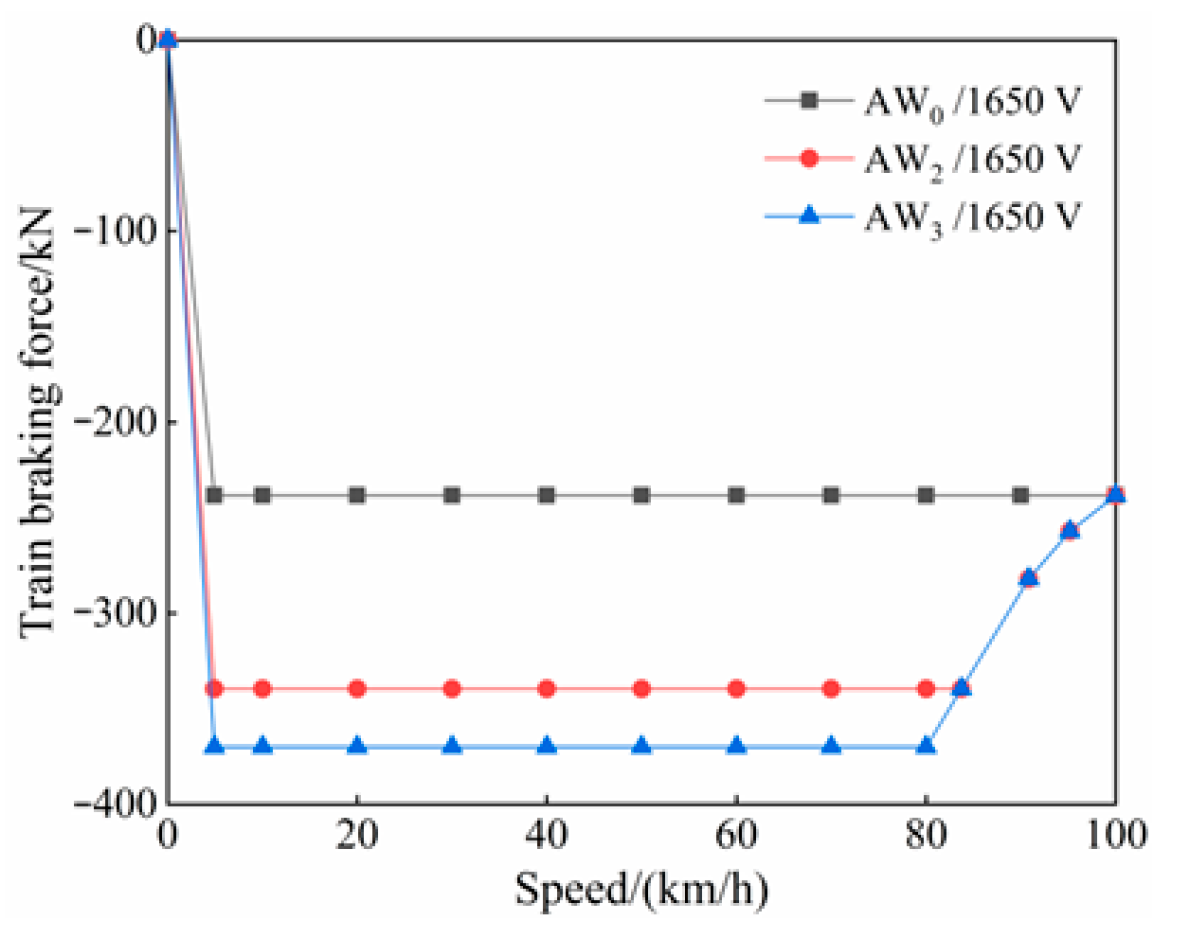

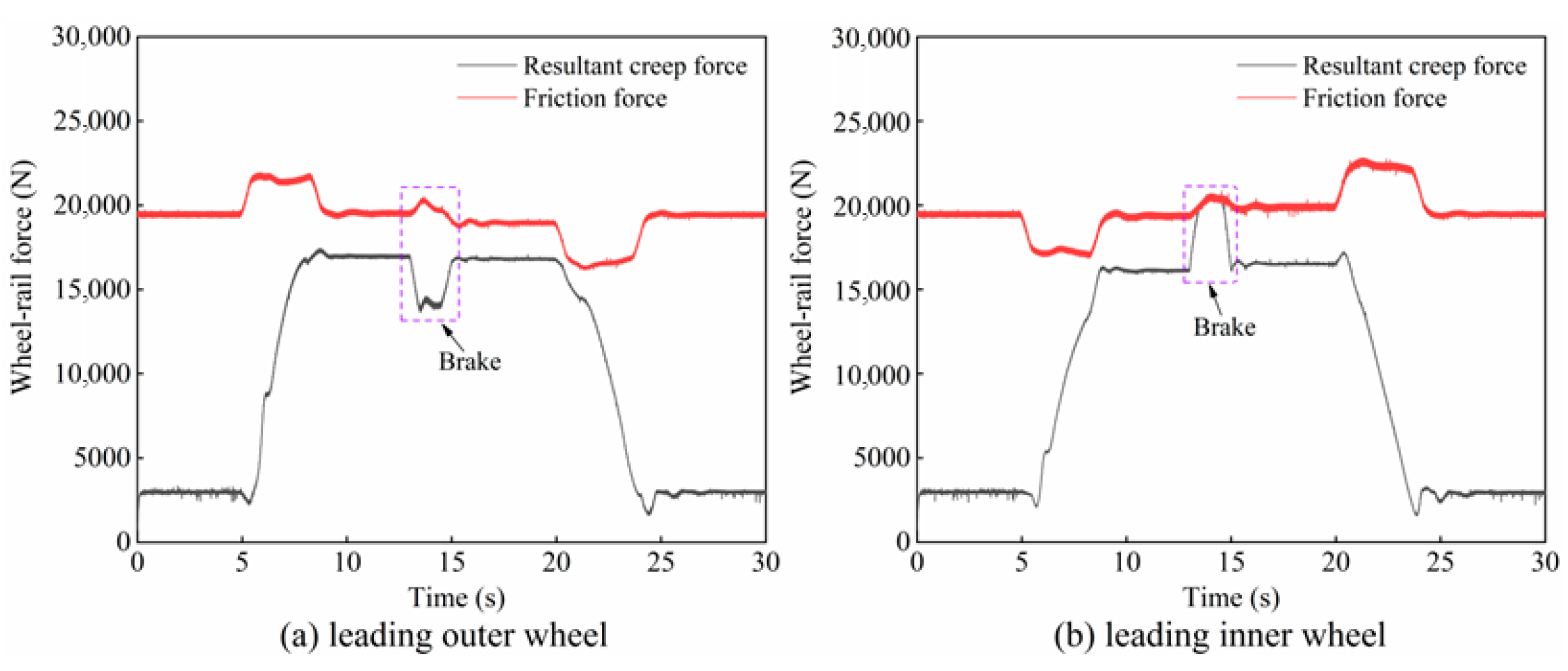

2.4. Creep Characteristics of the Wheel–Rail Interface During Braking

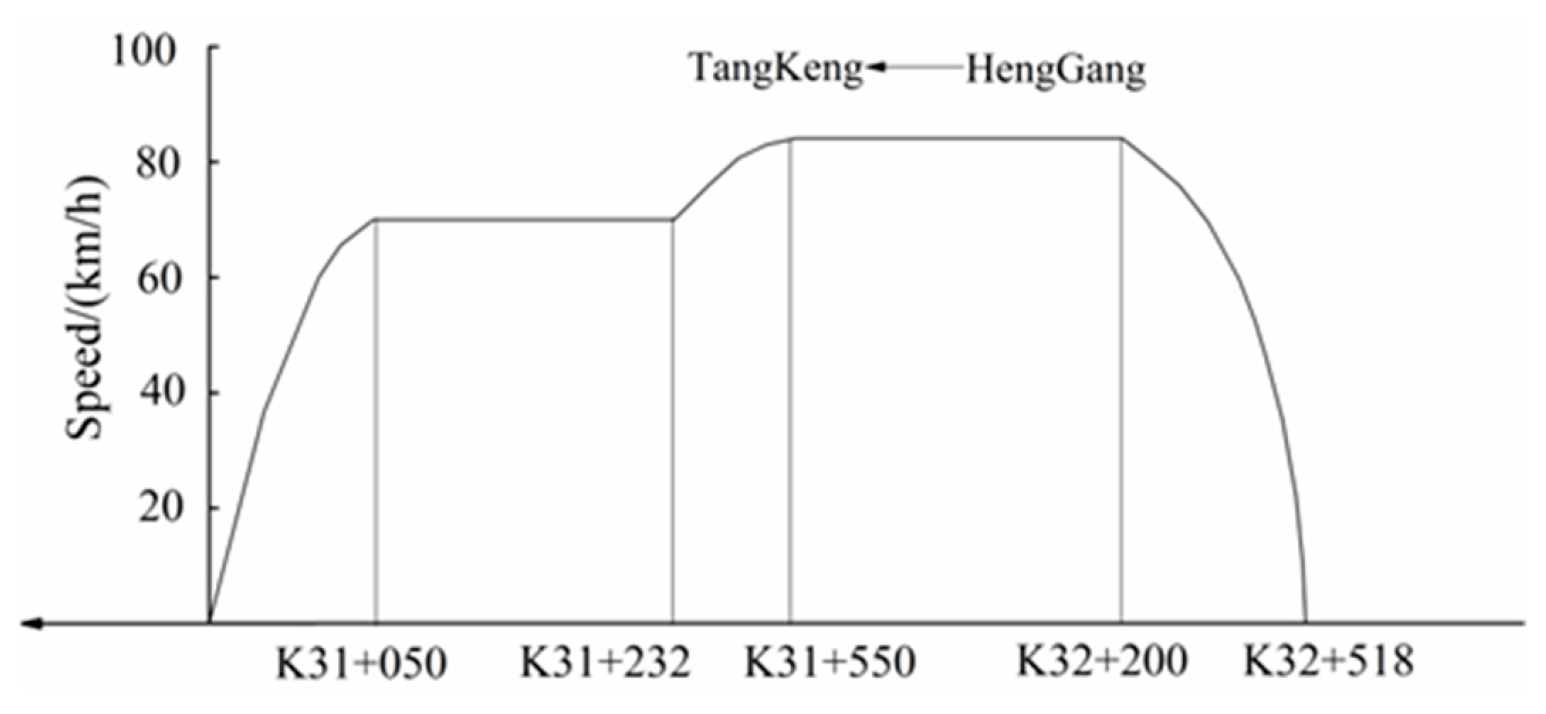

3. Case Study: Inner Rail Corrugation on Long Downhill Track

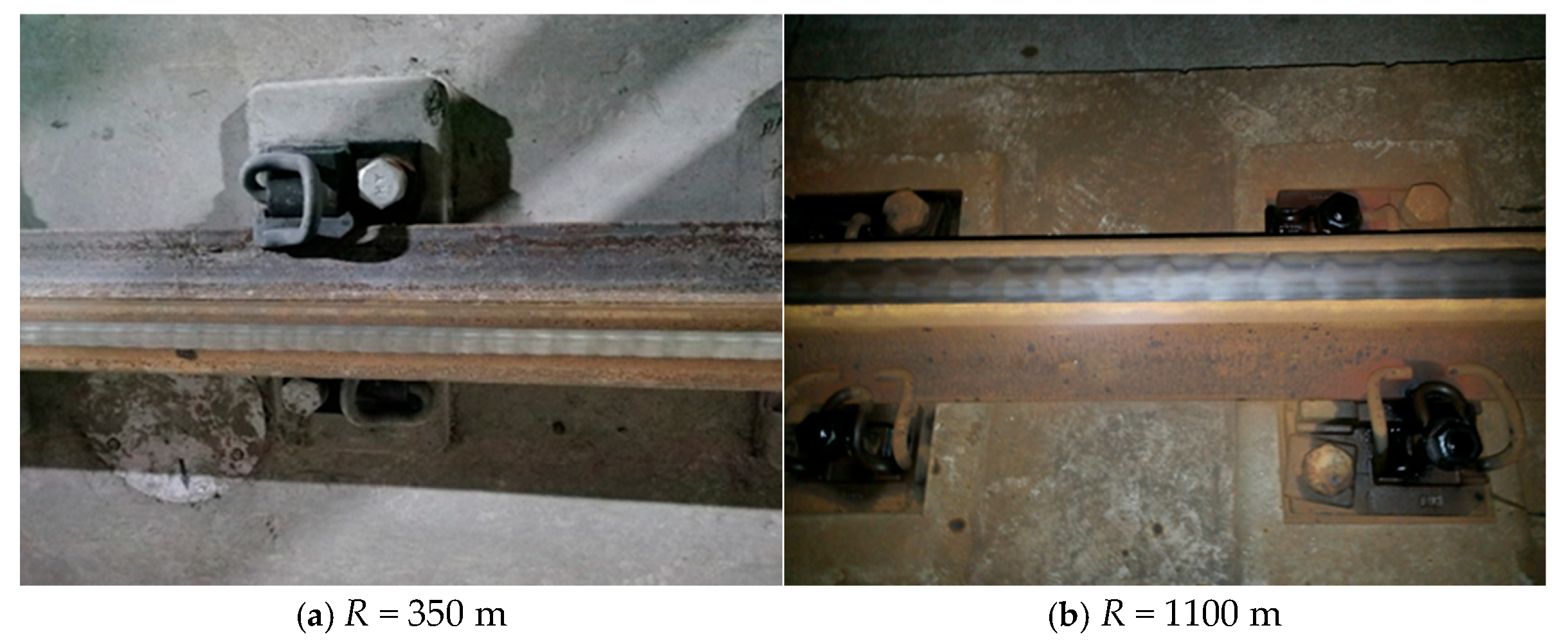

3.1. Phenomenon Description

3.2. Study on the Self-Excited Vibrations on the Long Downhill Curved Track

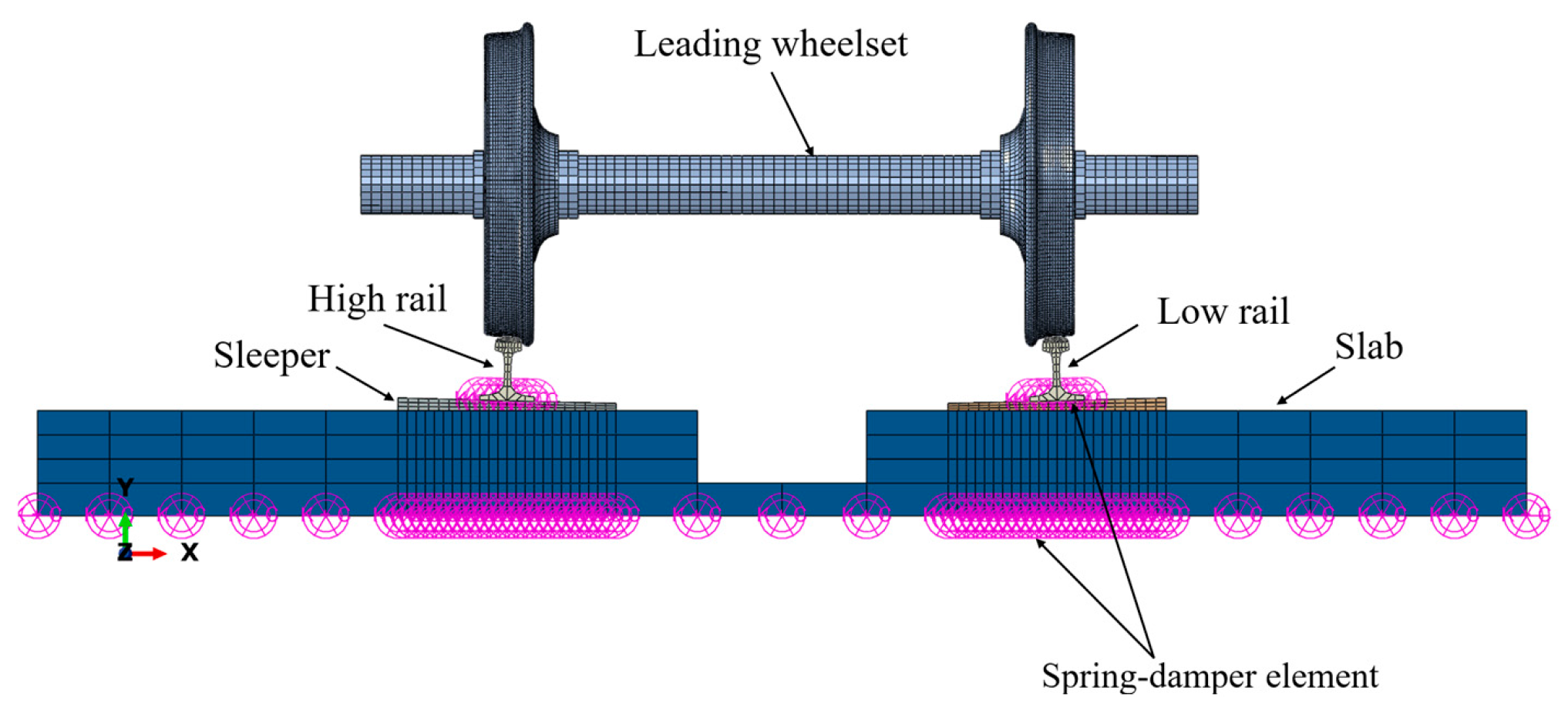

3.2.1. Finite Element Modeling

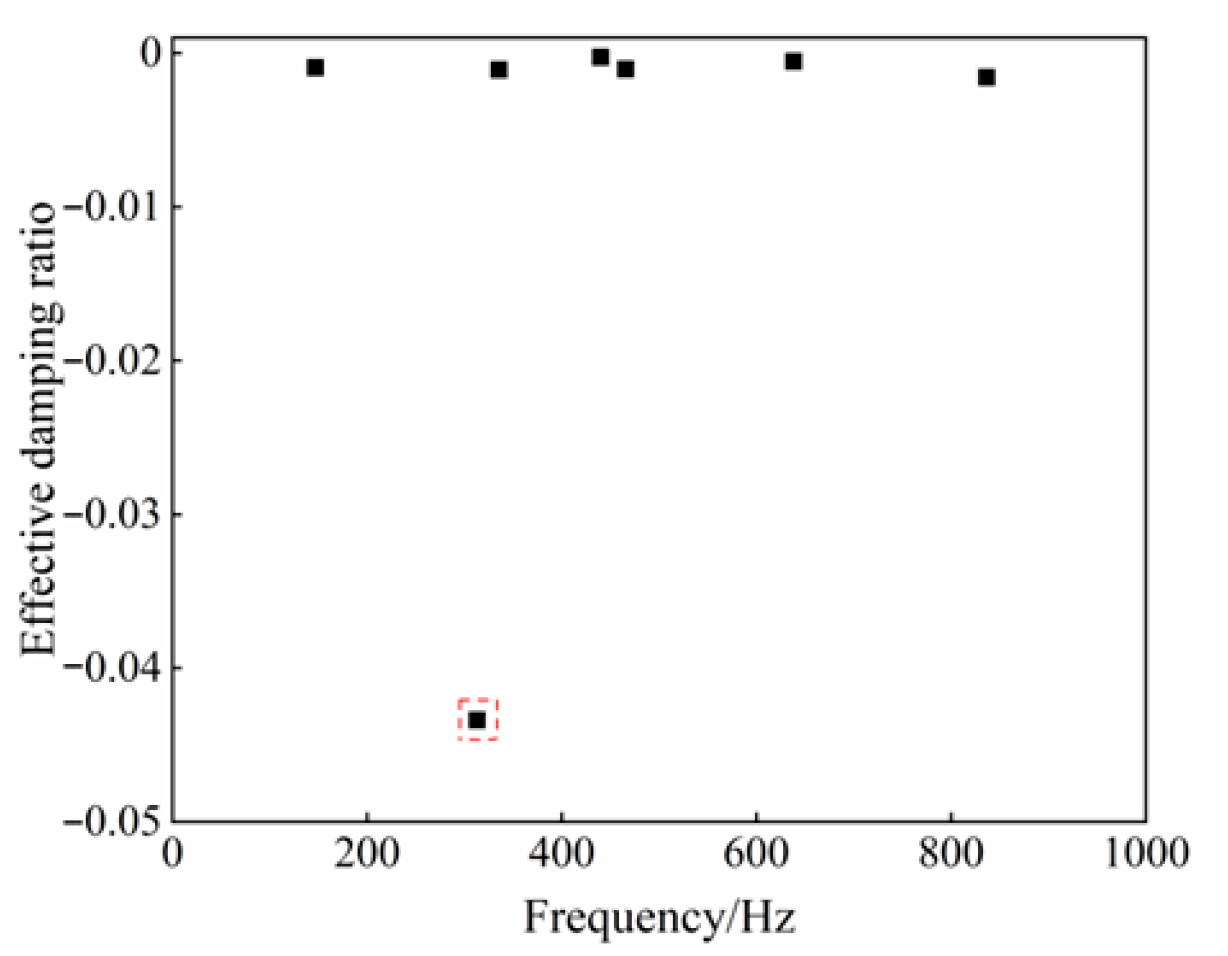

3.2.2. Complex Eigenvalue Analysis

3.2.3. Solution Procedure

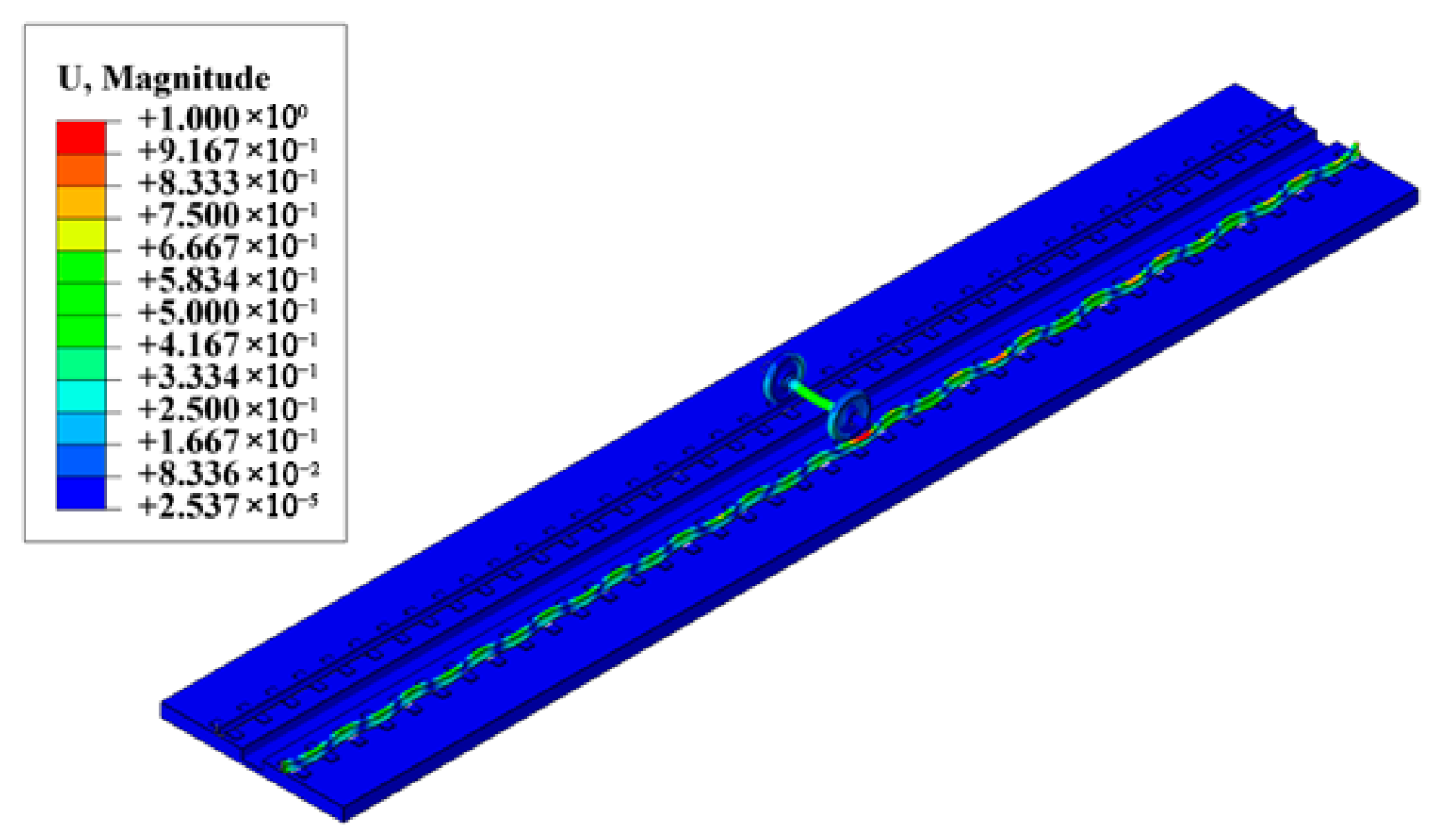

3.2.4. Numerical Simulation Results

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- During coasting on a large-radius curve, the creep forces at the contact interfaces generally remain unsaturated. This characteristic accounts for the markedly lower incidence of rail corrugation on large-radius curves in metro systems compared with that on small-radius curves.

- (2)

- During braking on a large-radius curve, the creep force on the guiding inner wheel may reach saturation, causing relative sliding between the wheel and rail. This braking-induced sliding can excite friction-induced self-excited oscillations, thereby promoting corrugation formation on the inner rail.

- (3)

- The train braking zone is a high-incidence area for rail corrugation on large-radius curves. Regulating the braking torque to prevent creep force saturation can effectively mitigate the progression of rail corrugation. This strategy offers a valuable reference for track maintenance.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| VTS | Vehicle–Track System |

References

- Dong, B.J.; Chen, G.X.; Song, Q.F.; Feng, X.H.; Ren, W.J.; Mei, G.M. Fatigue life analysis of subway e-clips under multiwavelength rail corrugation excitation. Fatigue Fract. Eng. Mater. Struct. 2024, 47, 3153–3170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, B.; Wu, X.W.; Chen, Z.H.; Wang, W.; Yang, N.R.; Liu, Y.; Liu, J.Z.; Mi, C.Y.; Chi, M.R. Fatigue failure mechanism of a metro bogie frame and its Mitigation method. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2025, 174, 109511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassie, S.L. Rail corrugation: Characteristics, causes, and treatments. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part F J. Rail Rapid Transit 2009, 223, 581–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, M.; Moto, T.; Takikawa, M. The effect of lateral creepage force on rail corrugation on low rail at sharp curves. Wear 2002, 253, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, W.; Horwood, R.J.; Meehan, P.; Wheatley, N. Analysis of rail corrugation in cornering. Wear 2008, 265, 1183–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saulot, A.; Descartes, S.; Berthier, Y. Sharp curved track corrugation: From corrugation observed on-site, to corrugation reproduced on simulators. Tribol. Int. 2009, 42, 1691–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hempelmann, K.; Knothe, K. An extended linear model for the prediction of short pitch corrugation. Wear 1996, 191, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Műller, S. A linear wheel–rail model to investigate stability and corrugation on straight track. Wear 2000, 243, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torstensson, P.; Pieringer, A.; Nielsen, J. Simulation of rail roughness growth on small radius curves using a non-Hertzian and non-steady wheel-rail contact model. Wear 2013, 314, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vila, P.; Baeza, L.; Martínez-Casas, J.; Carballeira, J. Rail corrugation growth accounting for the flexibility and rotation of the wheel set and the non-Hertzian and non-steady-state effects at contact patch. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 2014, 52, 92–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Guan, Q.; Wen, Z. Influence of P2 resonance of metro wheel–rail system on fatigue failure of rail fastening clips. Int. J. Rail Transp. 2025, 13, 539–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.L.; Ge, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Qi, Y.; Ding, H.; Guo, L.; Zhao, X. Mechanism of novel phenomenon of rail corrugation on small radius curves with rail joint in mountainous city metros. Ind. Lubr. Tribol. 2024, 77, 921–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Wang, W.D.; Liu, J.Z.; Sun, S.C. The transient response of high-speed wheel/rail rolling contact on “roaring rails” corrugation. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part F J. Rail Rapid Transit 2019, 233, 1068–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Q.; Wen, Z.; Liu, B.; Wang, H.; Liang, S. A new perspective on rail corrugation and its practical implications. Wear 2025, 564–565, 205743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.R.; Wu, T.X. The growth and mitigation of rail corrugation due to vibrational interference between moving wheels and resilient track. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 2020, 58, 1257–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, G.Q.; Yuan, Q.; Yang, X.Y.; Wu, X.W.; Xie, Q.L.; Guan, Q.H.; Li, W.; Wen, Z.F. On short-pitch rail corrugation of suburban express railway caused by localized rail-bending vibrations within the bogie wheelbase. Int. J. Rail Transp. 2025, 13, 1200–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Gao, L.; Xin, T.; Cai, X.; Wang, P. The dynamic resonance under multiple flexible wheelset-rail interactions and its influence on rail corrugation for high-speed railway. J. Sound Vib. 2021, 498, 115968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.Z.; Zhu, S.Y.; Yang, J.J.; Zhai, W.M. Evolution and formation mechanism of rail corrugation in high-speed railways involving the longitudinal wheel-track coupling relationship. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2024, 67, 3612–3625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.Q.; Simson, S. Wagon–track modelling and parametric study on rail corrugation initiation due to wheel stick-slip process on curved track. Wear 2008, 265, 1193–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.G.; Wang, P. Investigation of the generation mechanism of rail corrugation based on friction induced torsional vibration. Wear 2021, 468–469, 203593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.Q.; Lei, Z.Y. Trend analysis of rail corrugation on the metro based on wheel–rail stick-slip characteristics. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 2023, 62, 147–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockley, C.A.; Ko, P.L. An investigation of rail corrugation using friction-induced vibration theory. Wear 1988, 128, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wang, H.Y.; Wen, Z.F.; Du, X.; Wu, L.; Li, X.; Jin, X.S. An investigation into the mechanism of metro rail corrugation using experimental and theoretical methods. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part F J. Rail Rapid Transit 2015, 230, 1025–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.X.; Zhou, Z.R.; Ouyang, H.J.; Jin, X.S.; Zhu, M.H.; Liu, Q.Y. A finite element study on rail corrugation based on saturated creep force-induced self-excited vibration of a wheelset–track system. J. Sound Vib. 2010, 329, 4643–4655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.L.; Chen, G.X.; Ouyang, H.J. Study on the effect of track curve radius on friction-induced oscillation of a wheelset–track system. Tribol. Trans. 2019, 62, 688–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.X.; Zhang, S.; Wu, B.W.; Zhao, X.N.; Wen, Z.F.; Ouyang, H.J.; Zhu, M.H. Field measurement and model prediction of rail corrugation. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part F J. Rail Rapid Transit 2020, 234, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.J.; Chen, G.X.; Chen, Q.Y.; Feng, X.H.; Ren, W.J.; Mei, G.M. Mechanisms underlying rail corrugation on tracks equipped with Cologne-Egg fasteners. Tribol. Trans. 2024, 67, 1016–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, G.M.; Chen, G.X.; Yan, S.; Chen, R.X. Study on a heuristic wheelset structure without rail corrugation on sharply curved tracks. Shock Vib. 2021, 2021, 3874005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Beshbichi, O.; Wan, C.; Bruni, S.; Kassa, E. Complex eigenvalue analysis and parameters analysis to investigate the formation of railhead corrugation in sharp curves. Wear 2020, 450–451, 203150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourie, D.; Fröhling, R.; Heyns, S. Railhead corrugation resulting from mode-coupling instability in the presence of veering modes. Tribol. Int. 2020, 152, 106499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.H.; Wang, Y.L.; Ao, W.K.; Yang, Y.F.; Ni, Y.Q. Case study of fastener clip failure in small-radius curve track by field test and numerical simulation. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2026, 183, 110237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.X.; Cui, X.L.; Qian, W.J.; Mo, J.L.; Mei, G.M. Research on Rail Corrugation and Wheel Polygonal Wear in Railways, 3rd ed.; China Science Press: Beijing, China, 2025; pp. 70–99. ISBN 9787030806376. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Yao, X.; Wen, Z.; Hou, T. Influence of wheelset and track flexibility on short pitch rail corrugation on metro tracks with vanguard fasteners. Int. J. Rail Transp. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, W.J.; Huang, Z.Q.; Ouyang, H.; Chen, G.X.; Yang, H. Numerical investigation of the effects of rail vibration absorbers on wear behaviour of rail surface. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part J J. Eng. Tribol. 2018, 233, 424–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.F.; Chen, G.X.; Dong, B.J.; Ren, W.J.; Feng, X.H. Study on the formation mechanism for high rail corrugation. Tribol. Trans. 2024, 67, 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.J.; Chen, G.X.; Song, Q.F.; Feng, X.H.; Zhang, J.C.; Mei, G.M. Study on long-term tracking of rail corrugation and the influence of parameters. Wear 2023, 523, 204768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.Q. Study on rail corrugation on metro tracks and its suppression. Railw. Signal. Commun. 2014, 50, 18–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddyhoff, T.; Dobre, O.; Le Rouzic, J.; Gotzen, N.A.; Parton, H.; Dini, D. Friction induced vibration in windscreen wiper contacts. J. Vib. Acoust. 2015, 137, 041009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, J.; Do, H.; Kang, J. Investigation of friction induced vibration in lead screw system using FE model and its experimental validation. Appl. Acoust. 2017, 122, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.H.; Chen, G.X.; Dong, B.J.; Song, Q.F.; Ren, W.J. Study on the generation mechanism of curve squeal and its relationship with wheel/rail wear. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part F J. Rail Rapid Transit 2024, 238, 1084–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter Identifier | Value |

|---|---|

| Lateral suspension force at the left axle end FSLL (N) | 3240 |

| Lateral suspension force at the right axle end FSLR (N) | 3300 |

| Vertical suspension force at the right axle end FSVR (N) | 50,658 |

| Vertical suspension force at the left axle end FSVL (N) | 45,300 |

| Contact angle at the outer wheel δL | 11° |

| Contact angle at the inner wheel δR | 3.1° |

| Vertical stiffness of the fastener KRV (MN/m) | 40.73 |

| Vertical damping of the fastener CRV (N·s/m) | 9900 |

| Lateral stiffness of the fastener KRL (MN/m) | 8.79 |

| Lateral damping of the fastener CRL (N·s/m) | 1927.96 |

| Foundation support stiffness KF (MN/m) | 170 |

| Foundation support damping CF (N·s/m) | 31,000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Song, Q.; Hu, Y.; Wen, F.; Sang, H.; Kang, X.; Zhang, D. Mechanism of Inner Rail Corrugation on Large-Radius Curves in Metro Systems. Lubricants 2026, 14, 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants14010019

Song Q, Hu Y, Wen F, Sang H, Kang X, Zhang D. Mechanism of Inner Rail Corrugation on Large-Radius Curves in Metro Systems. Lubricants. 2026; 14(1):19. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants14010019

Chicago/Turabian StyleSong, Qifeng, Yan Hu, Feng Wen, Hutang Sang, Xi Kang, and Dapeng Zhang. 2026. "Mechanism of Inner Rail Corrugation on Large-Radius Curves in Metro Systems" Lubricants 14, no. 1: 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants14010019

APA StyleSong, Q., Hu, Y., Wen, F., Sang, H., Kang, X., & Zhang, D. (2026). Mechanism of Inner Rail Corrugation on Large-Radius Curves in Metro Systems. Lubricants, 14(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants14010019