Abstract

The wheel–rail friction coefficient is a critical factor influencing train traction and braking performance. Low-adhesion conditions not only limit the enhancement of railway transport capacity but are also the primary cause of surface damage such as scratches, delamination, and flat spots. This study employs femtosecond laser technology to fabricate wavy groove textures on U75V rail surfaces, systematically investigating the effects of the wavy angle and texture area ratio on friction enhancement under various medium conditions. Findings indicate that parameter-optimized textured surfaces not only significantly increase the coefficient of friction but also exhibit superior wear resistance, vibration damping, and noise reduction properties. The optimally designed wavy textured surface achieves significant friction enhancement under water conditions. Among the tested configurations, the surface with parameters θ = 150°@η = 30% demonstrated the most pronounced friction enhancement, achieving a coefficient of friction as high as 0.57—a 42.5% increase compared to the non-textured surface (NTS). This enhancement is attributed to the unique hydrophilic and anisotropic characteristics of the textured surface, where droplets tend to spread perpendicular to the sliding direction, thereby hindering the formation of a continuous lubricating film as a third body. Analysis of friction vibration signals reveals that textured surfaces exhibit lower vibration signal amplitudes and richer frequency components. Furthermore, comparison of Stribeck curves under different lubrication regimes for the θ = 150°@η = 30% specimen and NTS indicated an overall upward shift in the curve for the textured sample. The amplitude, energy, and wear extent of the textured surface consistently decreased across boundary lubrication, hydrodynamic lubrication, and mixed lubrication regimes. These findings provide crucial theoretical insights and technical guidance for addressing low-adhesion issues at the wheel–rail interface, offering significant potential to enhance wheel–rail adhesion characteristics in engineering applications.

1. Introduction

The adhesion state at the wheel–rail rolling contact interface directly affects train traction, braking, and overall operational performance, playing a crucial role in railway operations [1]. Operating in an open environment, the wheel–rail system is susceptible to significant influence from third-body media such as rain, snow, leaves, and oil contaminants [2,3,4,5]. A low-adhesion condition occurs when the wheel–rail adhesion falls below the level required for normal traction or braking, leading to phenomena like wheel slip and slide, which can damage wheel and rail surfaces. Moreover, low adhesion causes insufficient braking force, resulting in issues like Signals Passed at Danger (SPADs) [6] and, in severe cases, may even trigger collision accidents. The low-adhesion phenomenon in the wheel–rail relationship is one of the important challenges faced by the rail transit field [7,8,9]. Implementing effective adhesion enhancement measures is fundamental to ensuring transportation safety and efficiency. Currently, common approaches to mitigate low adhesion include sanding, installing grinding wheel tread cleaning devices, and anti-slip systems. However, these approaches have practical limitations: introducing large amounts of sand accelerates rail surface wear and may damage surrounding components like trucks and braking systems. Additionally, adding external equipment increases the complexity of the wheel–rail system [10].

In engineering applications, surface texturing technology has demonstrated unique advantages and been widely applied in mechanical seals, diesel engine piston rings, thrust bearings, and other fields, achieving remarkable results [11]. Notably, Costa et al. [12] pointed out in their 2022 study that recent academic papers on surface texture predominantly focus on friction reduction, with only 1‰ of research addressing friction enhancement characteristics. This significant imbalance in research stands in stark contrast to practical engineering applications, highlighting the urgency and importance of studying friction-enhancing surface textures. Texture morphology parameter design, as a core method for regulating the tribological properties of material surfaces, plays a crucial role in precisely intervening in the contact behavior at friction interfaces. Through rational design of texture parameters, directional control of the friction coefficient and proactive management of wear behavior can be effectively achieved. Joshi et al. [13] indicated that the friction regulation mechanism of surface textures essentially involves a dynamic competition between friction reduction and friction increase: on one hand, surface textures help capture wear debris and retain lubricants, thereby reducing friction and wear; on the other hand, boundary effects and localized stress concentration induced by surface patterns can increase the friction coefficient. Vrbka et al. [14] conducted rolling fatigue tests using a twin-disc testing machine and found that textured surfaces could improve contact fatigue life compared to non-textured surfaces, and increasing the number of micro-textures further significantly extended fatigue life. Xing et al. [15] further confirmed that appropriate wavy and linear groove designs could increase the average friction coefficient by more than 20% and 15%, respectively, with wavy grooves exhibiting superior friction enhancement. Shimizu et al. [16] investigated the effect of varying texture area ratio on the friction coefficient and found that at lower area ratios, the ability of textures to capture wear debris and reduce friction was relatively limited, while the adhesion of debris had a more pronounced influence, leading to an increasing trend in friction coefficient as the area ratio decreased. Given the persistent issue of significant directional bias in current surface texturing research, most studies focus solely on regulating a single texturing parameter to achieve more precise control over enhancing the friction coefficient at contact interfaces. The majority of these studies concentrate on texturing morphology regulation. While research on wave-shaped texturing has reached a relatively mature stage, there remains a lack of investigation into the impact of key design parameters—such as different angles and area ratios—on tribological performance. This study investigates the effects of five distinct angles and area ratios of wave-shaped textures on tribological performance. While achieving enhanced friction and wear resistance, monitoring vibration signals released during friction reveals that textured surfaces exhibit certain vibration damping and noise reduction capabilities.

Additionally, vibration signals during friction processes can be utilized to monitor interface conditions. Wang et al. [17] collected vibration signals from friction braking tests and conducted time–frequency analysis in conjunction with instantaneous friction coefficient variations, revealing that this method effectively evaluates the evolution of interface conditions during high-speed train braking. In another study, Wang et al. [18] acquired vibration signals from the wear tests of micro-textured AlSiTiN-coated carbide against titanium alloy. By analyzing the time–frequency characteristics and image features derived from short-time Fourier transform, they identified the optimal parameters for preparing the micro-textured AlSiTiN coating. Xing et al. [19] distinguished two signal categories with distinct amplitude-frequency characteristics by collecting vibration signals emitted from sliding friction pairs under different lubrication conditions. Results confirmed that friction-induced vibration signals correlate closely with friction states, validating this approach as a reliable friction state identification method. Based on the existing literature studies mentioned above, surface texturing technology is predominantly employed to achieve anti-friction properties. However, there are few reports on the ability to enhance friction and reduce wear through surface texturing treatment when confronting low-adhesion phenomena. This paper innovatively proposes a texturing treatment for rail surfaces to enhance friction, while simultaneously analyzing friction interface contact states through friction vibration signal analysis. This approach aims to conduct a systematic investigation into the friction enhancement mechanism.

This study investigates the friction enhancement effects and wear surface damage impacts of varying wave-shaped texture angles and texture area ratios on friction pairs using a high-frequency reciprocating friction and wear test platform. Based on a series of experimental results, the structural parameters of the wavy texture that yield optimal friction enhancement were determined. Throughout this process, friction vibration signals are collected to conduct multi-faceted analyses of the tribological performance differences on textured rail surfaces. Furthermore, under the condition of specific texture parameters, the Stribeck curves across different dynamic pressure parameters, as well as the evolution of wear conditions and friction vibration signals under various lubrication regimes, were systematically analyzed. The study aims to establish a vibration signal-based methodology for assessing wheel–rail adhesion states and to provide deeper insights into the underlying mechanisms of friction enhancement through surface texturing.

2. Experimental Procedures

2.1. Test Specimens

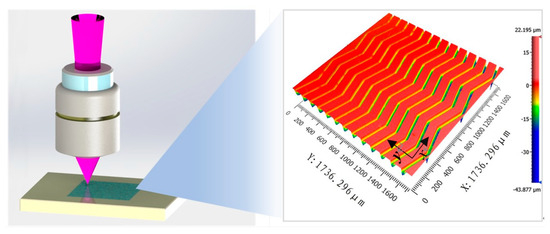

The substrate material used in this experiment was extracted from the head of a U75V rail, with dimensions of 30 mm × 25 mm × 3 mm. U75V rail steel is a eutectoid high-carbon low-alloy steel with a hardness of 330HV0.5, tensile strength (δb) greater than 980 MPa, and elongation after fracture exceeding 9%. The pin specimen for the friction pair was selected as 304 stainless steel (SUS304) with a diameter of 3 mm. The chemical compositions of both friction pair components are shown in Table 1. A femtosecond laser micro-nanofabrication system (Solstice Ace, Spectra-Physics, Andover, MA, USA), a high-power ultrafast femtosecond laser pulse system, was employed to fabricate the wavy texture patterns on the planar rail specimens, as illustrated in Figure 1. The prepared textured specimens exhibited groove width and depth of 40 μm and 20 μm, respectively. The area ratio η of the wavy texture was calculated using Equation (1), and specific parameters, including height, angle, and area ratio, are provided in Table 2. The laser system operated at a central wavelength of 800 nm with the following processing parameters: pulse frequency of 1 kHz, pulse duration of 104 fs, power of 200 MW, energy of 1.55 eV, scan speed of 0.004 mm/s, and 10 processing passes. To ensure a clean, flat, burr-free surface, both the non-textured regions before and after laser processing were ground and polished to a surface roughness Ra of approximately 0.8 μm.

Table 1.

Main components of rails and pins (mass fraction/%).

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of femtosecond laser processing wavy texture on steel rail surface.

Table 2.

Experimental group.

In the formula, S1 represents the area of the processed wavy texture (μm2), and S2 denotes the area of the region to be processed (μm2).

2.2. Tribological Test

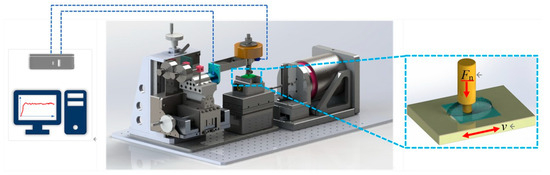

The tribological tests were conducted on a self-developed high-frequency reciprocating tribometer, whose schematic diagram is illustrated in Figure 2. A pin-on-flat contact configuration was adopted, with the upper specimen being the pin and the lower specimen being the rail flat. Before and after testing, both specimens were ultrasonically cleaned in anhydrous ethanol solution for 10 min and then dried with cold air from a blower. Subsequently, the tribological experiments were performed at room temperature (25 ± 1 °C). Preliminary tribological tests were carried out in a water-lubricated environment with the following parameters: normal load Fn = 20 N, reciprocating stroke L = 10 mm, frequency f = 2 Hz, and number of cycles N = 500. During testing, the upper specimen (pin) remained stationary while the lower specimen (flat) performed reciprocating motion. The relative sliding direction is indicated in Figure 2. Friction vibration signals were collected using a single-channel acquisition unit (model PXDAQ24260B), with the sensor magnetically mounted near the specimen.

Figure 2.

Schematic structure of the high-frequency reciprocating friction and wear tester.

To ensure the validity of the friction test results, each experiment was conducted with a minimum of three repetitions. After testing, the surface wear scars of the specimens were analyzed using optical microscopy (OM, Olympus BX53M, Tokyo, Japan), 3D optical profilometry (Zygo, ZeGageTM Pro HR, Middlefield, CT, USA), and scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Hitachi SU8010, Tokyo, Japan).

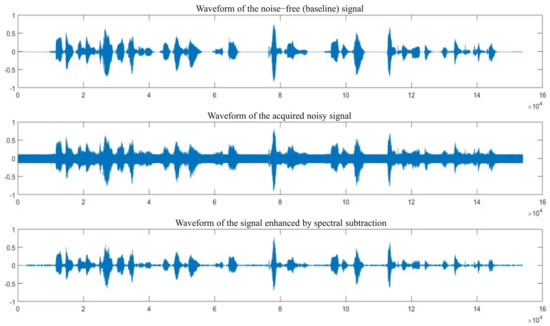

2.3. Friction Vibration Signal Processing

Considering the impact of environmental noise and equipment noise [20], we applied spectral subtraction to process the friction vibration signals in this paper. This algorithmic approach yielded a cleaner signal spectrum, enhancing data validity and precision. Figure 3 shows the signal diagram after spectral subtraction processing.

Figure 3.

Spectrum of the signal after spectral subtraction.

3. Experimental Results and Discussion

3.1. Tribological Characteristics

3.1.1. Time-Varying Friction Coefficient Curve

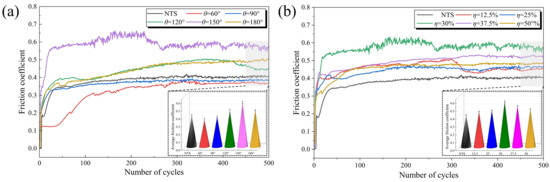

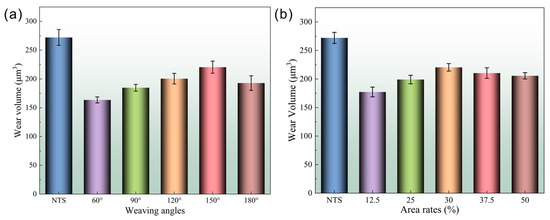

Figure 4 shows the time-varying friction coefficient curves corresponding to different texture angles under a 30% area ratio condition and different area ratios at an angle of 150°. As seen in Figure 4a, when the texture angle θ ≥ 120°, the friction coefficient remains higher than that of the NTS specimen throughout the entire friction stage. Among these, the wavy texture with θ = 150° exhibits the most effective friction enhancement, achieving a friction coefficient of 0.57. This indicates that altering the wave-shaped texture angle significantly influences the coefficient of friction, allowing for either friction enhancement or reduction at the contact interface by adjusting the texture angle. To further investigate the effect of area ratio on friction enhancement under θ = 150°, results are shown in Figure 4b. The optimal friction-increasing performance is achieved at an area ratio of η = 30%. Additionally, as the wave angle increased from θ = 60° to 180° and the area fraction rose from η = 12.5% to 50%, the average coefficient of friction (calculated from the last 50 friction coefficients during the cyclic stage) exhibited a trend of first increasing and then decreasing with changes in angle or area fraction. Notably, the textured surface with parameters θ = 150° and η = 30% attains an average friction coefficient of 0.57 during the steady-state phase, which is 42.5% higher than that of the non-textured surface (average friction coefficient of 0.4), demonstrating excellent friction enhancement performance.

Figure 4.

Time-varying curve of cyclic friction coefficient: (a) different texture angles; (b) different texture area ratios.

3.1.2. Analysis of Abrasion Conditions

Morphology curves were captured at the same locations on the wear track before and after the friction test. These curves were integrated, and the surface wear volume (V) was determined using Formula (2):

In the formula, V represents the wear volume (μm3), L denotes the wear track length (mm), and n indicates the number of sampling instances (n ≥ 3); Xi signifies the cross-sectional area (μm2) at that location prior to the friction test, while Yi indicates the cross-sectional area (μm2) at that location after the friction test. Both Xi and Yi are obtained through integration of the cross-sectional profile morphology.

Figure 5 shows the abrasion conditions of specimens with different texture parameters in areas excluding the texture pattern. As the wavy texture angle and area ratio increase, the wear volume of the specimens initially increases and then decreases in both cases. The specimen with texture parameters θ = 150° and η = 30% exhibits the largest wear volume (V = 220.5 μm3) among all textured specimens, yet this value is still 19.1% lower than that of the NTS specimen (V = 272.1 μm3). Overall, regardless of the wavy texture angle or area ratio, the textured surfaces show reduced wear compared to the NTS specimen. This improvement in wear resistance aligns with the widely reported benefits of friction-reducing textures [21]. It further confirms that even wavy textures designed for enhanced friction can effectively trap wear debris and retain lubricants, thereby continuously supplying lubrication to the friction interface and reducing wear of the friction pair.

Figure 5.

Plot of wear volume variation for different rail surfaces: (a) different angles; (b) different area rates.

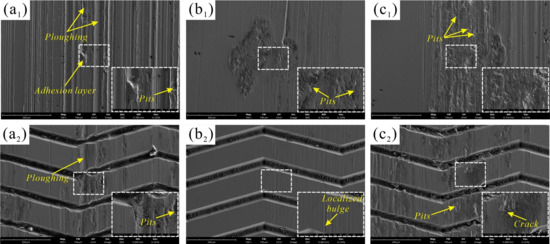

3.1.3. Analysis of Surface Damage Behavior

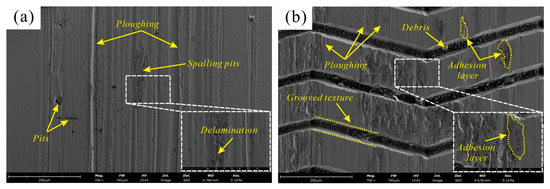

To further investigate the influence of surface texture on the damage behavior at the contact interface of U75V rail steel, Figure 6 presents the SEM micrographs of the worn surfaces of both the NTS specimen and the wavy-textured specimen (θ = 150°, η = 30%) after the friction and wear tests. Under a constant normal load, due to the presence of grooves, the contact area of the wavy-textured sample is smaller than that of the NTS sample. Consequently, the contact stress per unit area on the textured specimen surface increases. Simultaneously, the formation of numerous adhesive layers induces increased friction at the contact interfaces, leading to a significant rise in the coefficient of friction. Comparative analysis of Figure 6a,b reveals that the textured specimen—which exhibited a friction-enhancing effect—also demonstrates considerably improved wear resistance. On the non-textured regions of the textured surface, the number of ploughing is significantly reduced, while obvious debris accumulation is observed within the texture grooves. Notably, a large localized adhesive layer is present on the worn surface of the textured specimen, as shown in Figure 6b. In contrast, the NTS specimen shows distinctly different wear characteristics. Under the action of friction shear forces, the surface exhibits deep and wide ploughings accompanied by significant plastic deformation ridges on both sides, along with pits and spalling areas (see Figure 6a). These features indicate that the NTS specimen underwent a more severe wear process.

Figure 6.

Microscopic wear morphology of different U75V steel specimen surfaces: (a) NTS specimen surface; (b) Parametric (θ = 150°@η = 30%) specimen surface.

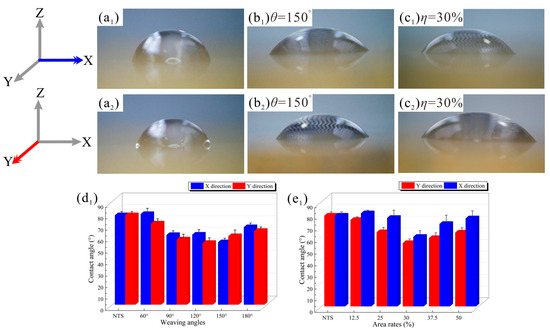

3.2. Wettability Analysis of Different Textured Surfaces

The wettability of solid surfaces generally reflects the ability to retain and spread lubricating media at the friction interface [22]. Precise design of surface micro-textures enables directional control over lubricant flow behavior, while modifications in texture channel morphology often lead to anisotropic wetting characteristics. The contact angle measurement parameters are droplet volume (1 mL), measurement time (5 s), ambient temperature (25 °C), humidity (30%), and droplet material (ultrapure water). Figure 7(a1–c2) present the contact angle (α) values of droplets along the X-direction and Y-direction for the NTS specimen and the specimen with wavy texture parameters θ = 150° and η = 0%. The results indicate that all textured surfaces exhibit hydrophilic properties (α< 90°; see Figure 7(d1,e1)) and demonstrate improved hydrophilicity compared to the NTS. Notably, variations in wavy texture parameters impart anisotropic wetting behavior to the surfaces. Among different texture angles, the specimens with θ = 120°~150° show superior hydrophilicity, with the lowest contact angle of 54.36° observed at θ = 150° (Figure 7(b1)), indicating easy droplet spreading along the X-direction. Regarding area ratio, as shown in Figure 7(c1,c2), the smallest contact angle is achieved at η = 30%. The contact angle may vary due to factors such as surface roughness [23]. As shown in Figure 6, the surface damage morphology analysis indicates that the textured specimen exhibits superior surface morphology and lower surface roughness. In summary, the textured surface with θ = 150° and η = 30% exhibits optimal hydrophilic characteristics. This enhanced hydrophilicity facilitates the expulsion of lubricating media toward both sides ahead of the pin during sliding, thereby inhibiting the formation of a continuous lubricating film at the friction interface. As a result, the actual contact area between the friction pairs increases, ultimately leading to an elevated friction coefficient.

Figure 7.

Contact angle of droplets on specimen surfaces at different directions: (a1) NTS&X-direction; (a2) NTS&Y-direction; (b1) θ = 150°&X-direction; (b2) θ = 150°&Y-direction; (c1) η = 30%&X-direction; (c2) η = 30%&Y-direction; (d1) average contact angle of specimens with different angles; (e1) average contact angle of specimens with different area rates.

In summary, based on the comprehensive analysis of surface wettability, friction coefficient, and wear behavior across different texture parameters, the specimen with texture parameters θ = 150° and η = 30% demonstrates the optimal overall performance in terms of friction enhancement and anti-wear capability.

3.3. Friction Vibration Signal Analysis

Time-domain waveforms and frequency spectra are essential tools for analyzing vibration signals [24]. The time-domain waveform visually represents the dynamic variation in vibration signals over time, enabling precise assessment of component wear conditions and detection of failures such as pitting and spalling induced by load impacts [25]. In contrast, the frequency spectrum focuses on the frequency characteristics of signals, where the frequency values reflect the diversity of vibrational components, and the amplitude magnitudes determine the prominence of corresponding vibrational modes within the signal [26].

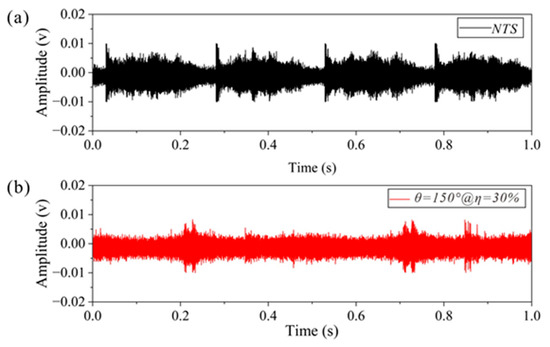

The vibration signals generated during the stable phase of the friction process were analyzed, focusing on a 1-s signal segment starting from the 450th cycle, as shown in Figure 8. Observation of the time-domain waveform of the friction vibration signal response curve during the stable phase reveals that the NTS specimen surface excites periodic, short-duration burst-type vibration signals during contact, with significantly higher amplitudes compared to the specimen with texture parameters θ = 150° and η = 30%. This indicates that the introduction of surface textures markedly reduces the intensity of friction-induced vibrations, suggesting an altered contact stress state and a smoother interaction at the textured interface during sliding.

Figure 8.

Time domain waveform of vibration signals: (a) the stable stage of the NTS specimen; (b) the stable stage of the specimen with parameters (θ = 150°@η = 30%).

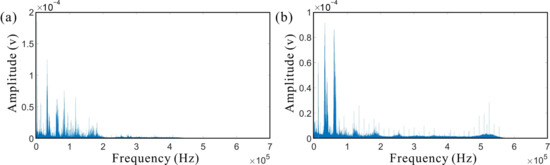

Figure 9 displays the amplitude-frequency spectra of signals during the stable phase for both the NTS specimen and the textured specimen with parameters θ = 150° and η = 30%. Analysis reveals that the dominant frequency components of both specimens are concentrated in the low-frequency range of 0~2 × 105 Hz. Notably, the textured specimen demonstrates lower spectral peak amplitudes compared to the NTS specimen. The NTS specimen reaches a maximum peak amplitude of approximately 1.25 × 10−4 V, whereas the peak amplitude of the textured specimen remains below 1 × 10−4 V. Furthermore, in the high-frequency range of 4–6 × 105 Hz, the textured specimen displays significant spectral components, while the NTS specimen shows only minimal amplitude in this region. These findings suggest that the introduction of wavy textures not only diversifies the types of signals generated during friction but also substantially enhances the intensity of high-frequency components. Therefore, the friction-induced vibration characteristics of the textured specimen are marked by reduced amplitudes in the low-frequency range and significantly strengthened high-frequency signal content.

Figure 9.

Spectrum diagram of stable stage: (a) NTS specimen; (b) Texture parameter (θ = 150°@η = 30%) specimen.

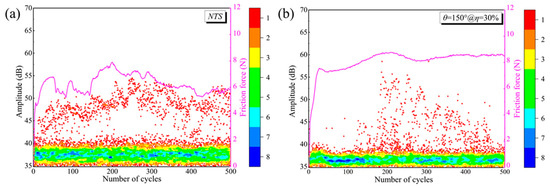

The friction coefficient formula indicates that friction force exhibits a linear relationship with the friction coefficient [27]. Figure 10 illustrates the evolution of friction force and signal amplitude over cycle counts for textured and non-textured specimens. We observe strong synchrony between friction force and signal on the time scale (cycle count). When friction force increases sharply, the contact state at the friction interface changes, accompanied by a sudden surge in the friction vibration signal. Compared to the NTS specimen, the textured specimen exhibits higher friction force at the contact interface, indicating the achievement of enhanced friction. Comparing the amplitude of the friction vibration signals reveals that the surface texturing treatment significantly reduces vibration and noise.

Figure 10.

Evolutionary Patterns of Friction Force and Friction Vibration Signal Amplitude: (a) NTS specimen; (b) Texture parameter (θ = 150°@η = 30%) specimen.

Therefore, the mechanism of increased friction and wear resistance in textured surfaces can be explained from two perspectives: On one hand, the groove edges of the textures continuously induce a micro-cutting effect on the friction pair during sliding, leading to an increased friction coefficient. Simultaneously, under specific textural conditions, adhesive effects between interfaces become dominant. The formation of extensive adhesive layers induces adhesive wear, further driving up the coefficient of friction. On the other hand, the groove structures function as reservoirs for wear debris and lubricating media. During motion, detached wear particles are captured by the grooves, thereby effectively mitigating oxidative wear and abrasive wear. It is noteworthy that the wavy texture, owing to its hydrophilic and anisotropic nature, facilitates the expulsion of lubricating media toward both sides ahead of the sliding counterpart. This inhibits the formation of a continuous third-body lubricating film, creating conditions favorable for boundary lubrication and even two-body wear, while also promoting the development of adhesive layers. From the perspective of friction vibration signal characteristics, the textured surface designed for friction enhancement exhibits vibration characteristics with lower amplitudes and a broader frequency distribution. In summary, these findings demonstrate that through rational design of surface textures, it is possible to synergistically enhance both friction and wear performance.

3.4. Analysis of Friction Enhancement Characteristics of Optimal Texture Parameters Under Different Lubrication Conditions

3.4.1. Stribeck Curves at Different Dynamic Pressure Parameters

This section investigates the variation in the friction coefficient on the contact surfaces of both the NTS specimen and textured specimens with parameters θ = 150° and η = 30% under different lubrication regimes by controlling the hydrodynamic parameter P (determined by lubricant viscosity η, sliding speed v, and applied load W). The lubricants used included deionized water with a dynamic viscosity of 1 mPa·s and imported Dow Corning dimethyl silicone oils with viscosities of 100 mPa·s, 500 mPa·s, 1000 mPa·s, and 10,000 mPa·s. While maintaining a constant applied load, the reciprocating speed v and lubricant viscosity η were varied to plot the Stribeck curves, thereby studying the influence of different hydrodynamic parameters on the lubrication state of the specimen contact surfaces. The NTS specimen served as the control group. The hydrodynamic parameter P is calculated using the following Formula (3) [15]:

In the formula, P represents the dynamic pressure parameter of the fluid (Pa), η denotes the dynamic viscosity of the lubricant (mPa·s), v indicates the velocity (m/s), and W signifies the load (N).

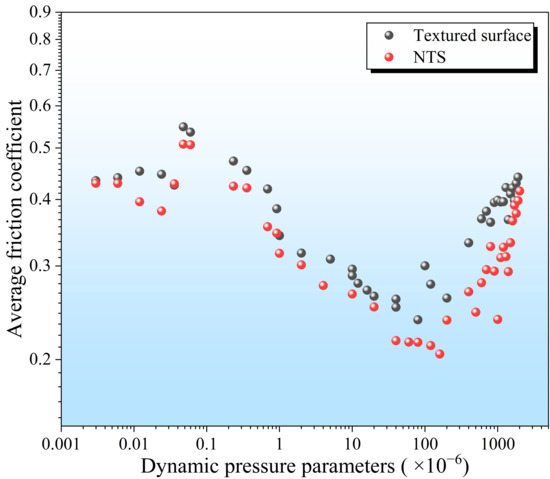

Friction and wear tests were conducted on both the NTS specimen and the textured specimen with parameters θ = 150° and η = 30%, yielding the variation curves under different hydrodynamic parameters shown in Figure 11. Each data point represents the average of three measurements. The obtained curves align well with the general form of the Stribeck curve [28]. Observations indicate that the friction coefficient exhibits a significant correlation with the hydrodynamic parameter P, and the textured surface consistently demonstrates higher friction coefficients than the NTS specimen. As the hydrodynamic parameter P increases, the friction coefficient generally shows a trend of initially decreasing and then increasing. When P < 0.1 × 10−6, the friction coefficients of both surfaces fluctuate only slightly, remaining around 0.51 and 0.57, respectively, indicating that both surfaces are in the boundary lubrication regime. Upon entering the mixed lubrication regime, the friction coefficient continues to decrease with increasing P, reaching its minimum at P = 100 × 10−6 Pa, where the friction coefficients of the NTS and textured specimens are 0.2 and 0.24, respectively. At this point, the lubrication state transitions from mixed lubrication to hydrodynamic lubrication. With further increase in the hydrodynamic parameter, the friction coefficients of both specimens begin to rise. Overall, the Stribeck curve of the textured surface is clearly shifted upward compared to that of the NTS.

Figure 11.

Stribeck curve with different dynamic pressure parameters.

3.4.2. Analysis of Wear Morphology Under Different Lubrication Conditions

Based on the Stribeck curves obtained above, a comparative analysis of the worn surfaces under different lubrication regimes in oil media was conducted using SEM. Figure 12(a1,a2) show the microscopic wear morphologies of the NTS and textured specimens under boundary lubrication conditions, revealing significant differences in their wear characteristics. The NTS specimen exhibits deep wear tracks with evident spalling pits and ploughings, indicating that the primary wear mechanisms are oxidative wear and abrasive wear. In contrast, the textured specimen, while displaying deep ploughings and minor spalling pits in the central wear track, is predominantly characterized by abrasive wear. The groove structures effectively capture wear debris, thereby reducing wear between the friction pairs. The groove structures effectively capture wear debris, thereby reducing wear between the friction pairs. During this stage, the ratio of lubricant film thickness to the composite surface roughness of the friction pair ranged between 0.4–1, resulting in inadequate lubrication performance. As a consequence, the normal load was directly supported by a large number of asperities. In addition, the limited friction-reducing capability of the lubricant further promoted the generation of wear debris and intensified mechanical wear.

Figure 12.

Wear morphology of NTS and texture parameters(θ = 150°@η = 30%) specimens in different lubricating conditions, the white dotted squares indicate a locally magnified view: (a1) NTS & boundary lubrication condition; (a2) Texture & boundary lubrication condition; (b1) NTS & mixed lubrication condition; (b2) Texture & mixed lubrication condition; (c1) NTS & hydrodynamic lubrication condition; (c2) Texture & hydrodynamic lubrication condition.

Under mixed lubrication conditions, the wear morphologies of the NTS and textured specimens are shown in Figure 12(b1,b2), respectively. Compared to the boundary lubrication regime, both types of specimens exhibit significantly mitigated wear, with smoother worn surfaces and markedly reduced wear track depths, indicating improved lubrication conditions at the contact interface. While the NTS specimen still shows evident ploughings and spalling traces, the textured specimen presents only minor and shallow wear tracks. This contrast demonstrates that the improved lubrication state effectively alleviates surface damage, confirming that the textured design significantly enhances the anti-wear performance of the contact surface under this lubrication regime.

Figure 12(c1,c2) present the surface damage morphologies of the NTS and textured specimens under hydrodynamic lubrication conditions. It can be clearly observed that both surfaces are largely free of plastic deformation caused by interfacial shear stresses. However, the NTS specimen exhibits extensive spalling and ploughings, while the textured specimen also shows numerous ploughings and spalling pits. These spalling pits are attributed to localized impact and transient high temperatures induced by the collapse of high-pressure cavitation bubbles, leading to cavitation erosion and fluid erosion [29]. Surface micro-cracks are likely caused by the oil wedge effect [30], wherein normal pressure forces lubricant into existing spalling pits, thereby aggravating surface damage. Overall, the extent of surface damage under hydrodynamic lubrication lies between that observed in boundary and mixed lubrication regimes—more severe than under mixed lubrication but significantly milder than under boundary lubrication conditions.

3.4.3. Analysis of Friction Vibration Signals Under Different Lubrication Conditions

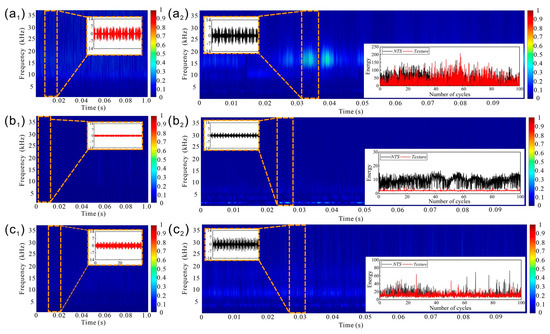

Friction vibration signals provide a quantitative representation of the dynamic evolution at contact interfaces, exhibiting a clear mapping relationship between their inherent signal characteristics and the friction state [31]. Accordingly, by analyzing these vibration signals, it is possible to uncover the intrinsic regulatory mechanism of surface textures on friction behavior and clarify the tribological performance of textured surfaces under various lubrication conditions [32], thereby overcoming the limitations of “black-box prediction”. To facilitate intuitive comparison of friction vibration signals between non-textured (NTS) and textured specimens under different lubrication regimes, normalized time–frequency representations were generated, as shown in Figure 13, illustrating the time–frequency characteristics of the signals for both specimen types across lubrication states.

Figure 13.

CWT maps of friction vibration signals for NTS specimens and texture specimens under different lubrication conditions: (a1) Texture & boundary lubrication condition; (a2) NTS & boundary lubrication condition; (b1) Texture & mixed lubrication condition; (b2) NTS & mixed lubrication condition; (c1) Texture & hydrodynamic lubrication condition; (c2) NTS & hydrodynamic lubrication condition.

For NTS specimens, under both boundary lubrication and hydrodynamic lubrication regimes, the friction vibration signals exhibit significant fluctuation amplitudes (see Figure 13(a2,c2)), which are notably higher than those observed under mixed lubrication conditions (see Figure 13(b2)). From an energy release perspective, the mixed lubrication state is characterized by low-energy features with minimal fluctuations (see Figure 13(b2)), reflected in the CWT map as an almost complete absence of high-frequency signals, as shown in Figure 13(b2). In contrast, boundary lubrication demonstrates high-energy characteristics with substantial fluctuations, where high-frequency signals are predominantly distributed within the 7.5–35 kHz (see Figure 13(a2)). For the textured specimen, both signal amplitude and energy reach their maximum under boundary lubrication, with fluctuation magnitudes significantly exceeding those in other regimes. The CWT map in Figure 13(a1) also reveals a predominance of high-frequency signals. Under mixed lubrication, the signal amplitude remains stable (see Figure 13(b1)), indicating consistent energy release from the textured surface and suggesting favorable lubrication conditions with uniformly distributed contact forces and minimized friction coefficient. In the hydrodynamic lubrication stage, as shown in Figure 13(c1), the occurrence of high-frequency signals is more frequent than in mixed lubrication, though low-frequency components remain dominant.

Figure 13(a1,a2) present the time–frequency characteristics and signal energy distribution of friction vibration signals in the steady-state stage under boundary lubrication for the textured and NTS specimens, respectively. A strong synchrony in the variation in signal amplitude and energy can be observed between the NTS and textured specimens, both exhibiting high-energy and high-amplitude signal characteristics. In the corresponding CWT maps, signals are distributed predominantly within the 7.5–35 kHz frequency band. As shown in Figure 12(a1,a2), distinct ploughing phenomena are evident under boundary lubrication. The formation of ploughing is accompanied by substantial energy release, along with deterioration of the contact interface condition, leading to a sharp increase in signal energy and amplitude. Moreover, due to the thin lubricating film under boundary lubrication, effective separation of the friction pairs is inadequate, resulting in intensified fluctuation of friction force and more pronounced amplitude variations in the friction vibration signals. Figure 13(b1,b2) illustrate the signal characteristics in the steady-state stage under mixed lubrication. The amplitude of friction vibration signals for the textured surface is significantly lower than that of the NTS specimen. This behavior is directly related to the magnitude of the interaction force (i.e., friction force) between the friction pairs. A comparison between boundary and mixed lubrication reveals that the signal amplitude and energy under boundary lubrication are substantially higher. Under mixed lubrication, normal pressure causes partial expulsion of the lubricant from the contact zone, leaving localized solid–solid contact regions. However, the ratio of lubricant film thickness to the composite surface roughness of the friction pair lies between 1–3. In this regime, both boundary and hydrodynamic lubrication films share the normal load. The presence of the hydrodynamic film effectively reduces the contact force acting directly on the asperities, significantly enhancing lubrication performance and thereby reducing friction and wear. This is ultimately reflected in a notable decrease in signal amplitude and energy. Figure 13(c1,c2) depict the friction vibration signals under hydrodynamic lubrication. In this regime, the signal amplitude and energy exhibit a unique intermediate state: lower than that under boundary lubrication but higher than under mixed lubrication. This phenomenon arises because, under hydrodynamic lubrication, the contact interface is fully separated by a continuous lubricating film, with the film thickness reaching 3–5 times the composite surface roughness of the friction pair. In this case, the interaction between the friction pairs is governed entirely by the viscous shear force of the lubricant, which increases significantly with sliding velocity, leading to enhanced friction and wear. It is worth noting that as the two surfaces are effectively separated by the lubricating film, mechanical wear is avoided. The dominant wear mechanisms transition to cavitation erosion, liquid-induced wear, and surface fatigue wear. The coupling of these mechanisms shapes the unique signal response characteristics under this lubrication condition. A comparative analysis of Figure 13(a1–c2) indicates that the amplitude and energy of the NTS specimen are consistently higher than those of the textured specimen across all lubrication regimes. This implies that surface texturing not only enhances anti-friction and anti-wear performance but also contributes to vibration damping and noise reduction. The effect is most pronounced under mixed lubrication, offering significant potential for improving ride comfort in high-speed train applications.

4. Conclusions

In this study, wavy surface textures with different structural parameters were fabricated on U75V rail specimens using femtosecond laser technology. The influence of various texture parameters on friction enhancement was systematically investigated through friction and wear tests, revealing the underlying friction-increasing mechanisms under different lubrication environments. Meanwhile, friction vibration signals under different lubrication regimes were monitored, providing a reliable basis for identifying the friction state of textured surfaces. The main conclusions are as follows:

(1) Comparative analysis of the effects of texture angle and area ratio on the friction coefficient and wear behavior showed that when the texture angle θ ≥ 120°, the friction coefficient exceeded that of the NTS specimen, indicating a friction-enhancing effect. The most pronounced enhancement was observed at θ = 150°. In contrast, specimens with smaller angles (θ = 60° and 90°) exhibited friction-reducing characteristics. With a fixed texture angle of θ = 150°, textured specimens with different area ratios consistently demonstrated higher friction coefficients than the NTS specimen. At an area ratio η = 30%, the average friction coefficient reached 0.57, representing a 42.5% increase compared to the NTS specimen.

(2) Analysis of the surface wettability under different texture parameters revealed that the textured surfaces exhibited hydrophilic and anisotropic characteristics. Among them, the specimen with parameters (θ = 150°, η = 30%) showed the smallest contact angle, indicating the strongest hydrophilicity, with droplets spreading preferentially in the X-direction. This property facilitates the expulsion of lubricant to both sides during friction, hindering the formation of a continuous lubricating film and thereby promoting boundary lubrication conditions conducive to adhesive wear. In addition, the texture grooves effectively trap wear debris and lubricant, reducing abrasive and oxidative wear. As a result, the wear volume of this specimen was 19.1% lower than that of the NTS specimen, achieving a synergistic optimization of friction enhancement and wear resistance.

(3) The introduction of texture significantly altered the characteristics of the friction vibration signals. During the stable friction phase, the maximum amplitude of the vibration signal for the textured specimen was below 1 × 10−4 V, with frequencies distributed between 0~6 × 105 Hz, whereas the NTS specimen exhibited values of 1.25 × 10−4 V and 0~2 × 105 Hz, respectively. A systematic study of the lubrication behavior of textured surfaces under different dynamic pressure parameters revealed that the Stribeck curves of textured surfaces exhibited a significant overall upward shift compared to NTS specimens, confirming their friction-enhancing properties. Further analysis of different lubrication states reveals a variation pattern where boundary lubrication is superior to fluid dynamic lubrication, which in turn is superior to mixed lubrication.

Due to the significant differences in contact pressure and sliding speed between laboratory conditions and actual service conditions, the obtained research results cannot be directly applied to real wheel–rail systems. The core contribution of our work lies in exploring the underlying mechanisms under near-idealized conditions. We demonstrate the principle feasibility of regulating interfacial friction behavior and enhancing friction-wear performance through surface texturing.

Author Contributions

J.Z.: Investigation, Visualization, Data curation and Writing of the original draft. Z.W.: Investigation, Visualization, Supervision. L.M.: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Funding acquisition and Writing—review & editing. J.W., Y.W. and Z.B.: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology. M.S.: Conceptualization, Investigation, Visualization, Supervision and Writing—review & editing.All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 52375181 and 52061012), Natural Science Foundation Project of Jiangxi Province (nos. 20224ACB204012) and Technology Research and Development Project from the CHINA RAILWAY (N2021T012).

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ma, H.; Niu, Y.; Zou, X.C.; Zhang, J. Experimental Study of Effects of the Third Medium on the Maximum Friction Coefficient between Wheel and Rail for High-Speed Trains. Shock Vib. 2021, 2021, 6904346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.Y.; Chen, B.; Cai, Y.W.; Wang, J. Experimental investigation of high-speed wheel-rail adhesion characteristics under large creepage and water conditions. Wear 2024, 540, 205254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.S. Research Progress of High-Speed Wheel-Rail Relationship. Lubricants 2022, 10, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galas, R.; Omasta, M.; Shi, L.-B.; Ding, H.; Wang, W.-J.; Krupka, I.; Hartl, M. The low adhesion problem: The effect of environmental conditions on adhesion in rolling-sliding contact. Tribol. Int. 2020, 151, 106521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Wen, Z.; Wang, H.; Jin, X. Numerical analysis on wheel/rail adhesion under mixed contamination of oil and water with surface roughness. Wear 2014, 314, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Chen, D.; Shi, J.; Li, Z. Research on wheel-rail dynamic interaction of high-speed railway under low adhesion condition. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 157, 107935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.C.; Liang, P.; Guo, F.; Li, S.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, F. The Influence of Scratches on the Tribological Performance of Friction Pairs Made of Different Materials under Water-Lubrication Conditions. Lubricants 2023, 11, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Xiao, G.; An, B.; Wu, T.; Shen, Q. Numerical study of wheel/rail dynamic interactions for high-speed rail vehicles under low adhesion conditions during traction. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2022, 137, 106266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, G.; Wu, B.; Yao, L.; Shen, Q. The traction behaviour of high-speed train under low adhesion condition. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2022, 131, 105858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.F.; Ling, L.; Wang, J.; Zhai, W. A numerical study on tread wear and fatigue damage of railway wheels subjected to anti-slip control. Friction 2023, 11, 1470–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.; Wood, R.J.K. Tribological performance of surface texturing in mechanical applications-a review. Surface Topogr.-Metrol. Prop. 2020, 8, 043001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, H.L.; Schille, J.; Rosenkranz, A. Tailored surface textures to increase friction-A review. Friction 2022, 10, 1285–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, G.S.; Putignano, C.; Gaudiuso, C.; Stark, T.; Kiedrowski, T.; Ancona, A.; Carbone, G. Effects of the micro surface texturing in lubricated non-conformal point contacts. Tribol. Int. 2018, 127, 296–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrbka, M.; Šamánek, O.; Šperka, P.; Návrat, T.; Křupka, I.; Hartl, M. Effect of surface texturing on rolling contact fatigue within mixed lubricated non-conformal rolling/sliding contacts. Tribol. Int. 2010, 43, 1457–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Deng, J.; Wu, Z.; Wu, F. High friction and low wear properties of laser-textured ceramic surface under dry friction. Opt. Laser Technol. 2017, 93, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, J.; Nakayama, T.; Watanabe, K.; Yamamoto, T.; Onuki, T.; Ojima, H.; Zhou, L. Friction characteristics of mechanically microtextured metal surface in dry sliding. Tribol. Int. 2020, 149, 105634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, Z.W.; Mo, J.L.; Zhu, S.; Gou, Q. Evaluation of the dynamic behaviors of a train braking system considering disc-block interface characteristics. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2023, 192, 110234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Tong, X.; Yang, S.; Han, P. Analysis of friction and wear vibration signals in Micro-Textured coated Cemented Carbide and Titanium Alloys using the STFT-CWT method. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2025, 224, 112237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, P.; Li, G.; Gao, H.; Wang, G. Experimental investigation on identifying friction state in lubricated tribosystem based on friction-induced vibration signals. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2020, 138, 106590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.Y.; Pan, Y.L.; Zhao, X.Z. Humanoid Identification of Fabric Material Properties by Vibration Spectrum Analysis. Sensors 2018, 18, 1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Liu, Y.; Mostaghimi, J.; Zhang, N. Effect of laser preparation strategy on surface wettability and tribological properties under starved lubrication. Tribol. Int. 2024, 191, 109107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, S.; Bai, P.; Jia, W.; Xu, Q.; Meng, Y.; Ma, L.; Tian, Y. Surface wettability effect on aqueous lubrication: Van der Waals and hydration force competition induced adhesive friction. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 599, 667–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özakin, B.; Gültekin, K. Synergetic effect of hybrid surface treatment on the mechanical properties of adhesively bonded AA2024-T3 joints. J. Adhes. 2025, 101, 1033–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash Kumar, J.; Chauhan, P.S.; Prakash Pandit, P. Time domain vibration analysis techniques for condition monitoring of rolling element bearing: A review. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 62, 6336–6340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.; Cheng, Y.; Wu, J.; Zhu, H. Cross-domain intelligent diagnostics for rotating machinery using domain adaptive and adversarial networks. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2024, 42, 100722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, R.F., Jr.; Areias, I.A.D.S.; Gomes, G.F. Fault detection and diagnosis using vibration signal analysis in frequency domain for electric motors considering different real fault types. Sens. Rev. 2021, 41, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oestringer, L.J.; Proppe, C. On the calculation of a dry friction coefficient. PAMM 2019, 19, e201900407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Gutierrez, R.; Kirkby, T.; Bouassida, H.; Hilbert, M.; Yu, M.; Reddyhoff, T. Complete Stribeck curve prediction by applying machine learning to acoustic emission data from a lubricated sliding contact. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2025, 241, 113544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Chen, A.; Yu, Y.; Li, J. Investigation into the erosion damage mechanism of High-Temperature, High-Pressure, and High-Speed gasflow on metal surfaces. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2025, 167, 108976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, M.F.; Antunes, F.V.; Prates, P.A.; Branco, R.; Vojtek, T. Effect of Young’s modulus on fatigue crack growth. Int. J. Fatigue 2020, 132, 105375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.F.; Ta, W.R.; Zhou, Y.H. Estimation of the friction coefficient by identifying the evolution of rough surface topography. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2024, 125, 181601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Ni, H.; Wang, P.; Chen, H. Investigation on the tribological performance of micro-dimples textured surface combined with longitudinal or transverse vibration under hydrodynamic lubrication. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2020, 174, 105474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).