1. Introduction

Road traffic safety remains a critical global concern. With the rapid advancement of the automotive industry and electronic control technologies, Advanced Driving Assistance Systems (ADAS) and Autonomous Driving (AD) technologies are increasingly becoming standard features in modern vehicles. The core mission of these systems is to enhance driving safety, optimize ride comfort, and reduce driver workload [

1]. However, the fundamental prerequisite for both ADAS and AD algorithms to achieve safe and efficient vehicle control lies in the accurate perception of the vehicle and its external environment [

2,

3]. Among various environmental factors, the tire-road friction coefficient (TRFC)—a key physical parameter characterizing the limits of longitudinal and lateral force transmission between the tire and the road surface—directly influences braking distance, steering limits, and driving efficiency [

4]. It is undoubtedly one of the most critical variables in vehicle control systems.

Moreover, accurate estimation of TRFC is also essential for improving driving comfort and optimizing vehicle energy economy. Smooth acceleration, deceleration, and cornering require the control system to operate delicately within a range that approaches, but never exceeds, the physical limits of traction. Furthermore, for AD systems aiming to make fully independent decisions, precise road friction information is a prerequisite for global path planning and local trajectory generation. Examples include predicting a safe speed ahead of a curve or adopting more conservative driving strategies in adverse weather conditions.

Therefore, research into highly reliable and low-cost TRFC estimation methods holds significant theoretical value and engineering importance for overcoming current performance limitations of ADAS, ensuring driving safety, and enhancing overall travel quality. This paper focuses on an in-depth investigation of a fusion-based TRFC estimation technique that utilizes weather and road image information, aiming to provide key technical support for the development of safer and more intelligent next-generation vehicle control systems.

2. Related Work

For mass-produced vehicles equipped with conventional sensors, the TRFC is a parameter that cannot be measured directly. Numerous scholars have developed various methods to estimate TRFC, which can be broadly categorized into two types: cause-based methods and effect-based methods. The former typically requires additional sensors to measure and analyze factors influencing friction variation—such as road texture and tire contact characteristics—to estimate TRFC. The latter focuses on analyzing the dynamic response of the vehicle during driving to infer the friction coefficient based on vehicle dynamics [

5].

TRFC is complexly influenced by multiple factors including road material, surface conditions (e.g., dry or wet), tire properties, and temperature. Quan et al. deployed PVDF piezoelectric films in the tire inner liner to develop an intelligent tire model. Using finite element analysis and neural networks to estimate tire forces, they achieved high-precision TRFC estimation (with an error of 5.14%) via a brush model optimized with a genetic algorithm [

6]. In addition to piezoelectric sensors, tri-axial accelerometers are also commonly used in intelligent tires. Zou et al. transformed acceleration signals into a rotating coordinate system to extract contact patch length and lateral tire deformation directly from longitudinal and lateral acceleration features. They estimated the friction coefficient using a brush model fitted via least squares [

7]. Differing from vehicle-state-focused methods, Yu et al. systematically investigated the coupling effects of multiple factors such as road texture, tire pressure, and speed, and applied a BP neural network to predict macroscopic road friction coefficients [

8]. Han et al. focused on road roughness and texture, proposing a TRFC estimation method that considers effective contact characteristics between the tire and three-dimensional road surfaces. By integrating an effective contact area ratio into the LuGre tire model and optimizing vertical force transmission with a multi-point contact method, they achieved estimation using normalization and an unscented Kalman filter [

9].

Ye et al. introduced an adaptive tire stiffness-based TRFC estimation method. By analyzing the relationship between tire–road contact patch length and vertical load, they established an adaptive theoretical model for tire stiffness and incorporated it as a state variable into an improved fast-converging square-root cubature Kalman filter. This significantly enhanced estimation accuracy and convergence speed under various driving conditions, including extreme scenarios such as tire damage [

10]. Tao et al. proposed a two-stage TRFC estimation scheme based on two robust proportional multiple integral observers and a multilayer perceptron. By introducing a threshold screening mechanism to filter out invalid data frames, the accuracy and generalization capability of the MLP estimator were substantially improved [

11]. Zhang et al. developed a TRFC estimation framework based on a novel tire model and an improved square-root cubature Kalman filter (ISCKF). The novel tire model adaptively computes stiffness and effective friction coefficients to enhance force calculation accuracy, while the ISCKF adaptively updates measurement noise covariance based on the maximum correntropy criterion. This approach demonstrates strong robustness against abnormal noise interference and good adaptability to uncertainties in road friction distribution [

12].

However, most effect-based methods rely heavily on model accuracy and external excitation; their performance degrades significantly under low-excitation conditions. To overcome these limitations, many researchers have combined the strengths of various approaches to develop optimized fusion estimation methods. Wang et al. proposed a TRFC estimation framework that integrates event-triggered cubature Kalman filtering (ETCKF) with an extended Kalman neural network (EKFNet). The ETCKF handles sensor data loss, while the EKFNet uses a neural network to predict Kalman gains and optimize estimation performance [

13]. Zhao et al. introduced an adaptive TRFC estimation framework that fuses visual and vehicle dynamic information. Multi-temporal image fusion technology was employed to enhance road condition recognition, combined with a residual adaptive unscented Kalman filter (UKF) to improve estimation accuracy and robustness [

14].

In terms of environmental perception, weather is a critical factor affecting TRFC and can be used to assist in its estimation. With the rapid development of deep learning, convolutional neural networks have demonstrated remarkable performance in various computer vision tasks, leading to their widespread use in weather recognition. Xia et al. developed a simplified model termed ResNet15 based on ResNet50. Using convolutional layers of ResNet15 to extract weather features, the model incorporates four residual modules to facilitate feature propagation via shortcuts, followed by a fully connected layer and a Softmax classifier for weather image classification [

15]. Xiao et al. proposed MeteCNN, a novel CNN architecture based on VGG16, which embeds squeeze-and-excitation attention modules and introduces dilated convolutions (dilation rate = 2) in the initial and final convolutional layers. This model achieved a classification accuracy of 92.68% on a self-built dataset, outperforming mainstream models such as VGG, ResNet, and EfficientNet [

16]. However, these methods rely solely on CNN features for weather classification, neglecting weather-sensitive cues such as illumination changes and contrast variations, which limits their accuracy. Li et al. proposed a multi-feature weighted fusion method that extracts handcrafted weather-related features (e.g., haze, contrast, brightness) and fuses them with CNN features into a high-dimensional vector for weather image classification. This approach improved weather recognition accuracy compared to using CNN features alone [

17]. Nevertheless, manually extracting various weather features is cumbersome and requires extensive parameter tuning, resulting in poor robustness.

Although many researchers have applied neural networks to recognize road conditions, limited dataset diversity often restricts the generalization capability of these models, leading to unreliable performance in complex and varying driving environments. Studies have shown that directly using neural network outputs can cause oscillatory predictions, which is detrimental to TRFC estimation [

18,

19,

20,

21]. Guo et al. proposed a vision-vehicle dynamics fusion framework for estimating peak TRFC. A lightweight CNN identifies road type to determine a friction coefficient range, while a UKF estimates the friction coefficient based on vehicle dynamic states. After spatiotemporal synchronization, a confidence-based fusion strategy refines the final result [

22]. Although this confidence-based fusion reduces the impact of misclassified road images, the vision-based module fails to provide a stable and correct friction coefficient range when the vehicle encounters unseen road types not included in the training dataset.

To address these challenges, this paper innovatively proposes a fusion estimation method for TRFC that utilizes both weather and road image information, without requiring additional sensors—only a single onboard camera. The contributions of this work are as follows:

- (1)

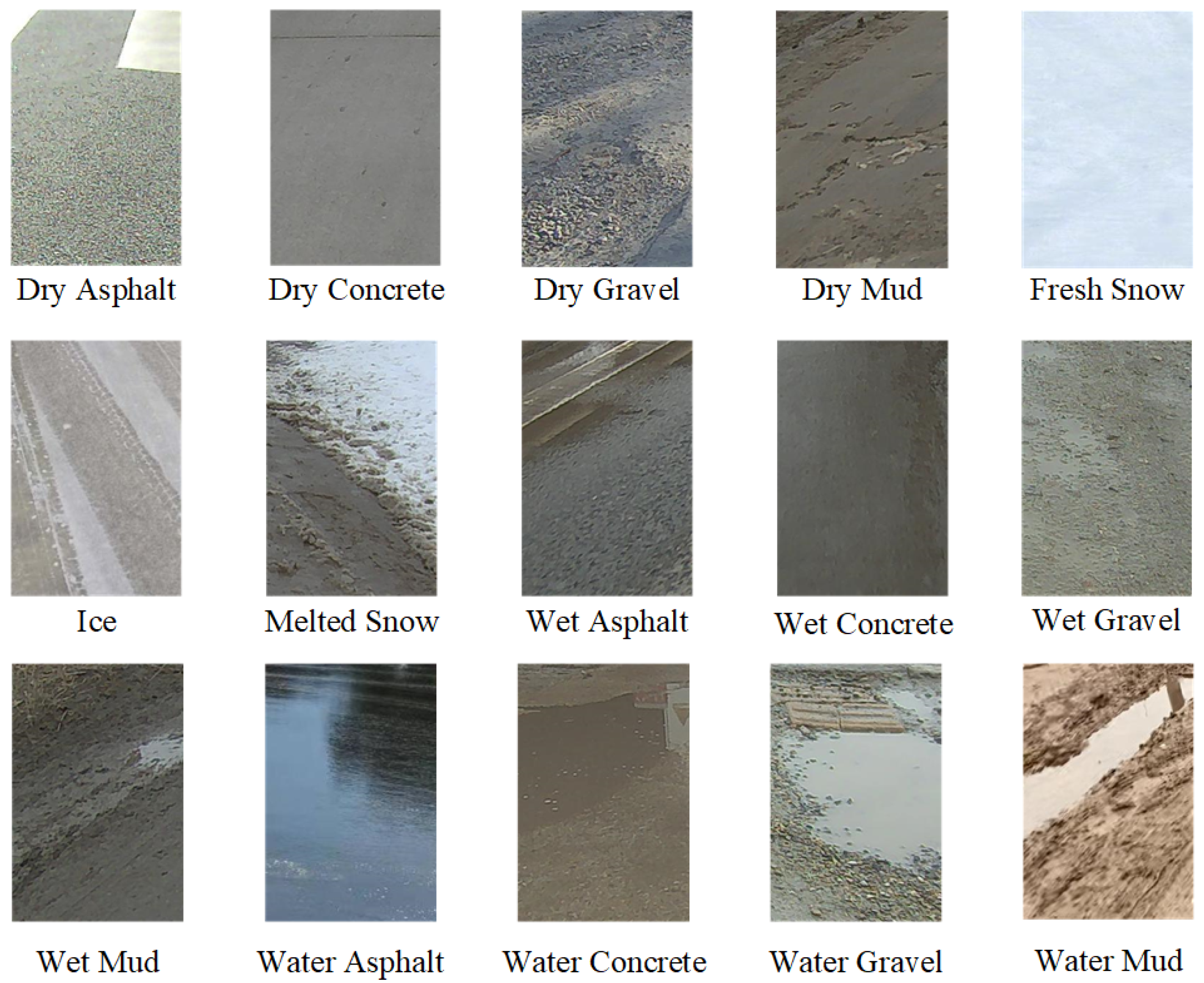

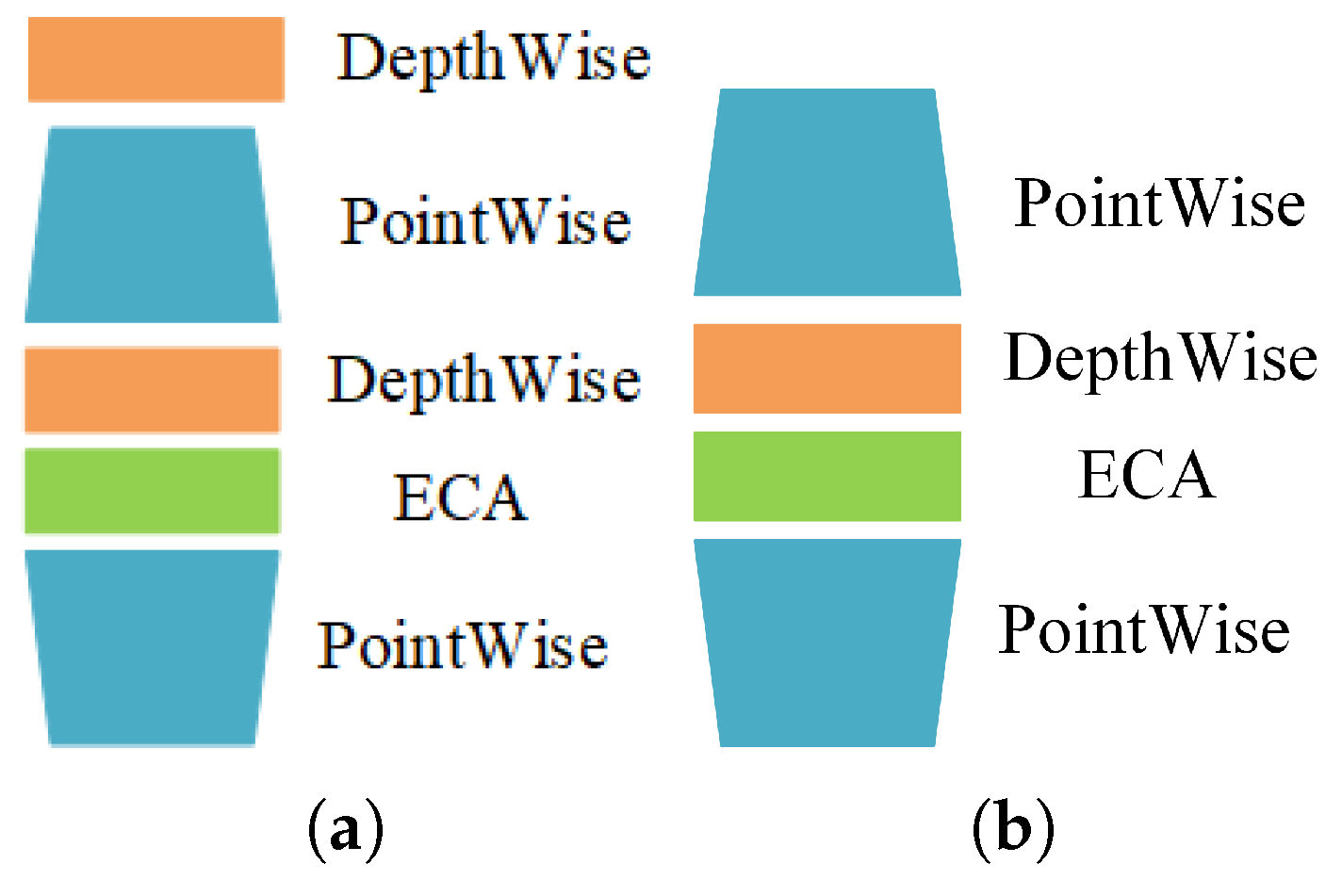

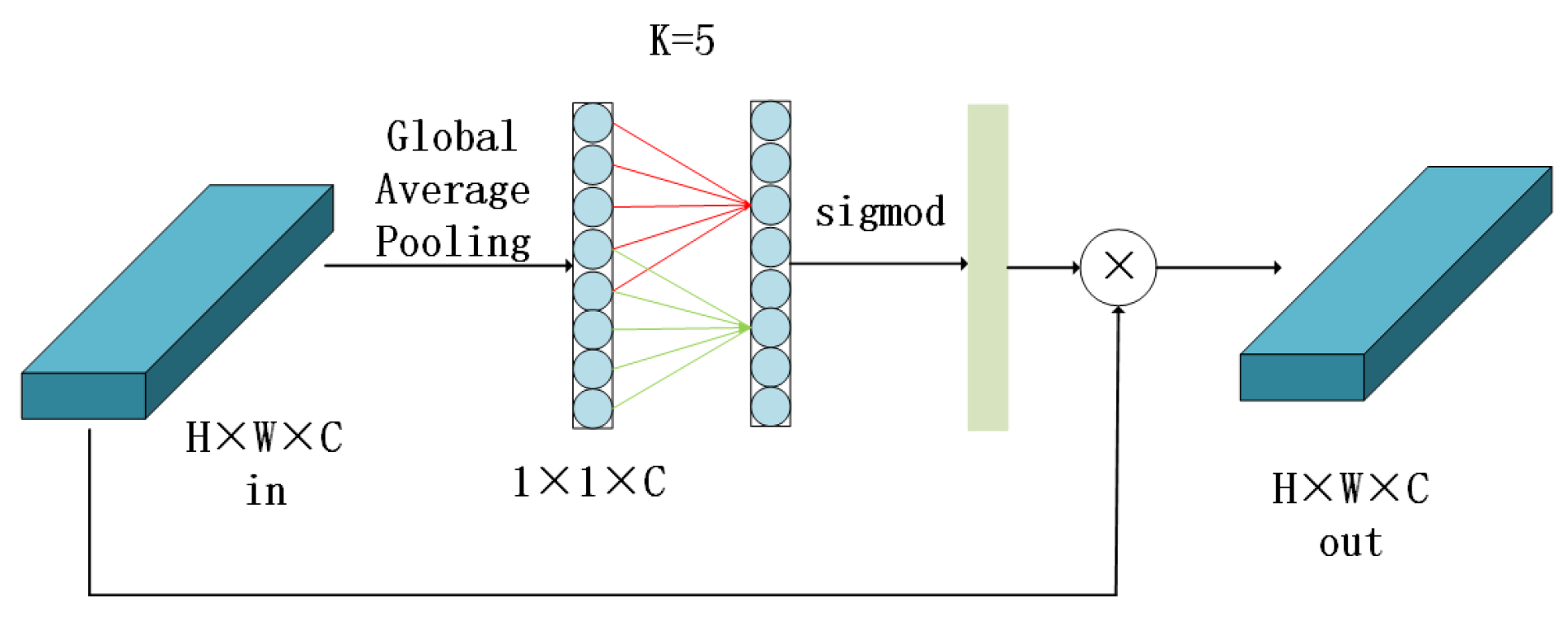

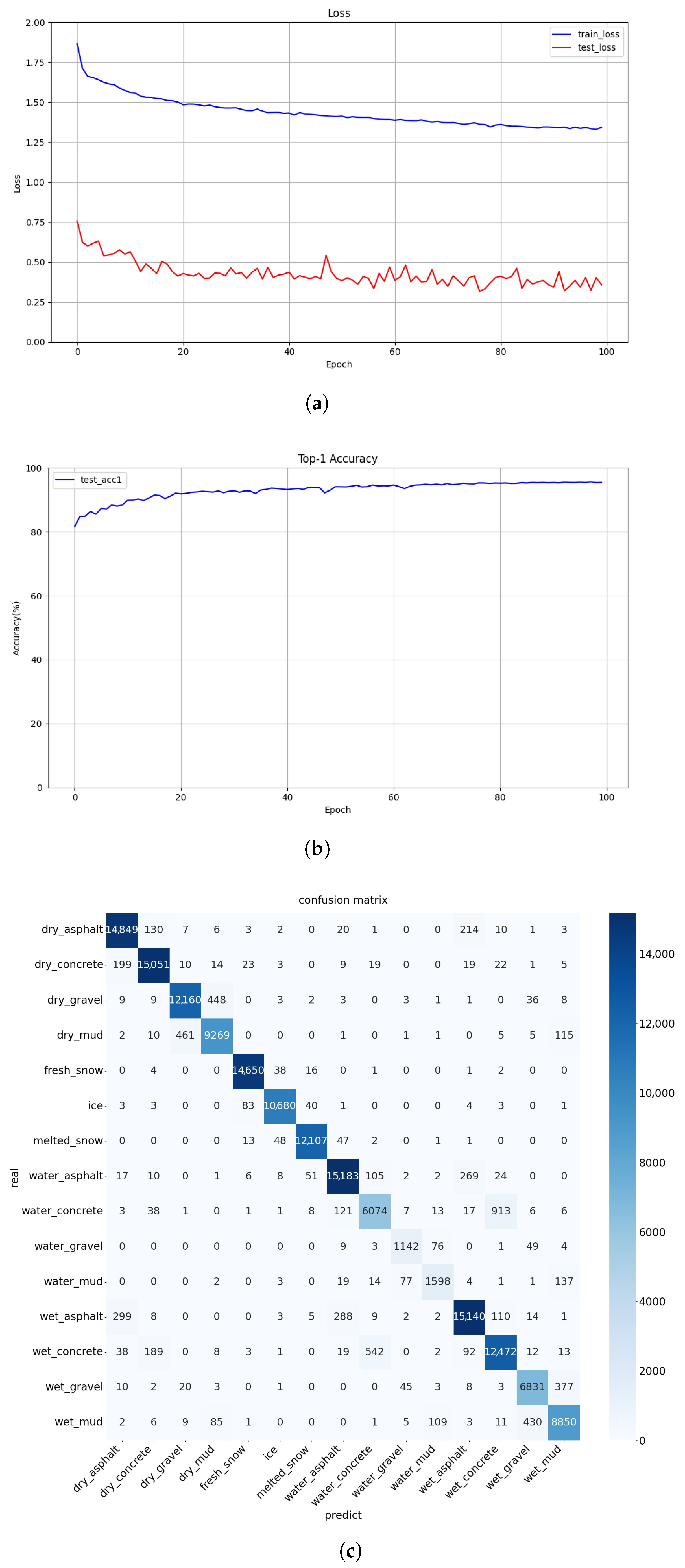

We incorporate the Efficient Channel Attention (ECA) mechanism into MobileNetV4-ConvSmall, achieving an accuracy of 95.63% in recognizing 15 different road types while maintaining a lightweight model architecture.

- (2)

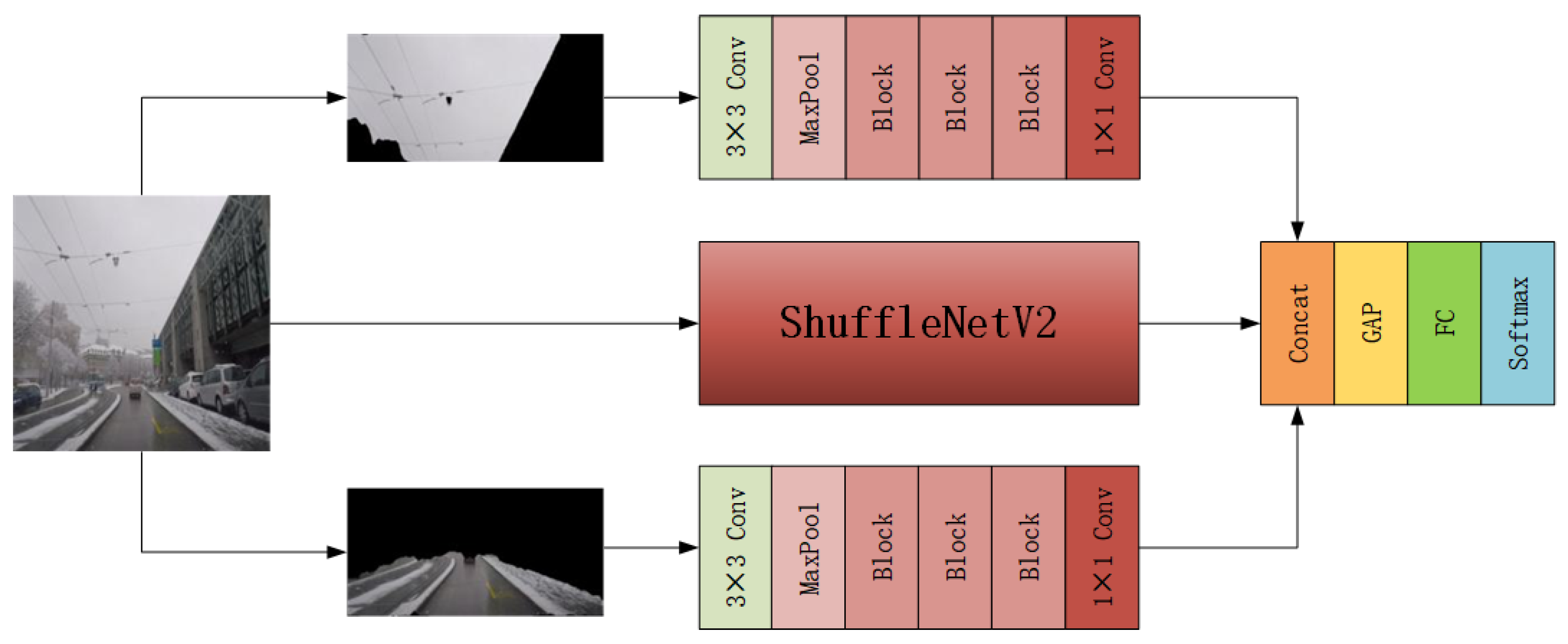

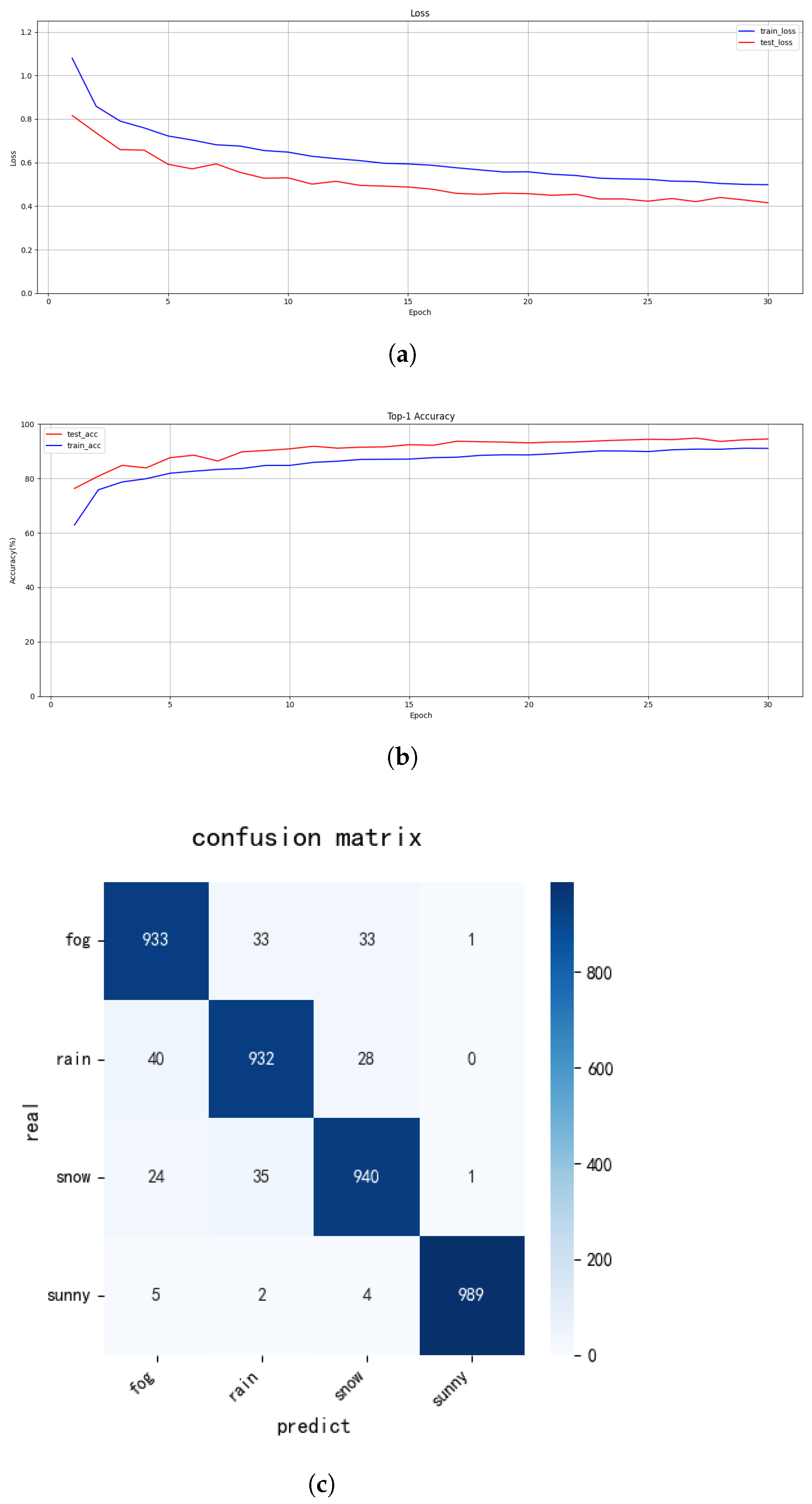

We develop a lightweight three-branch convolutional neural network that simultaneously captures sky, road, and global image features for effective weather recognition.

- (3)

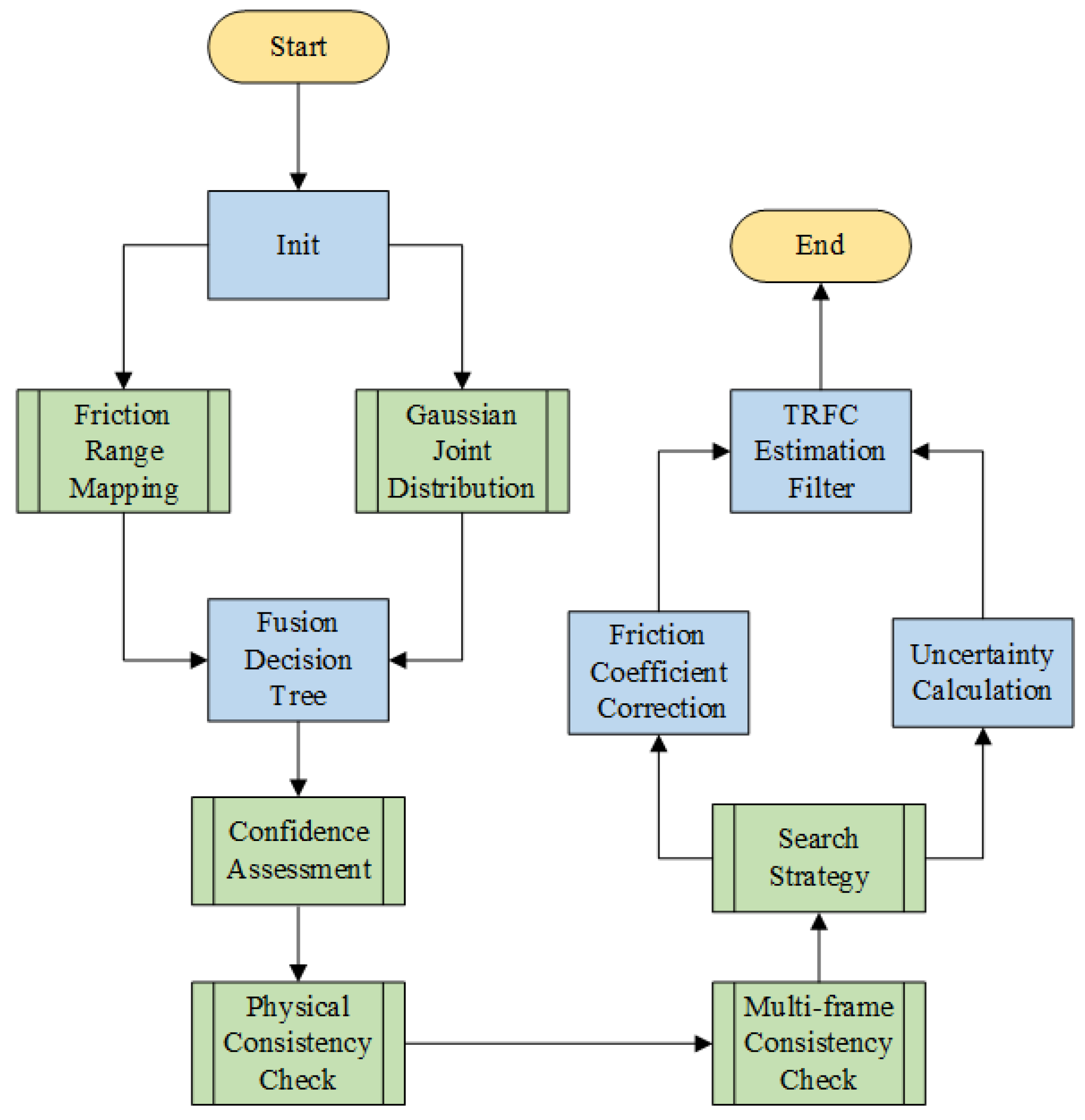

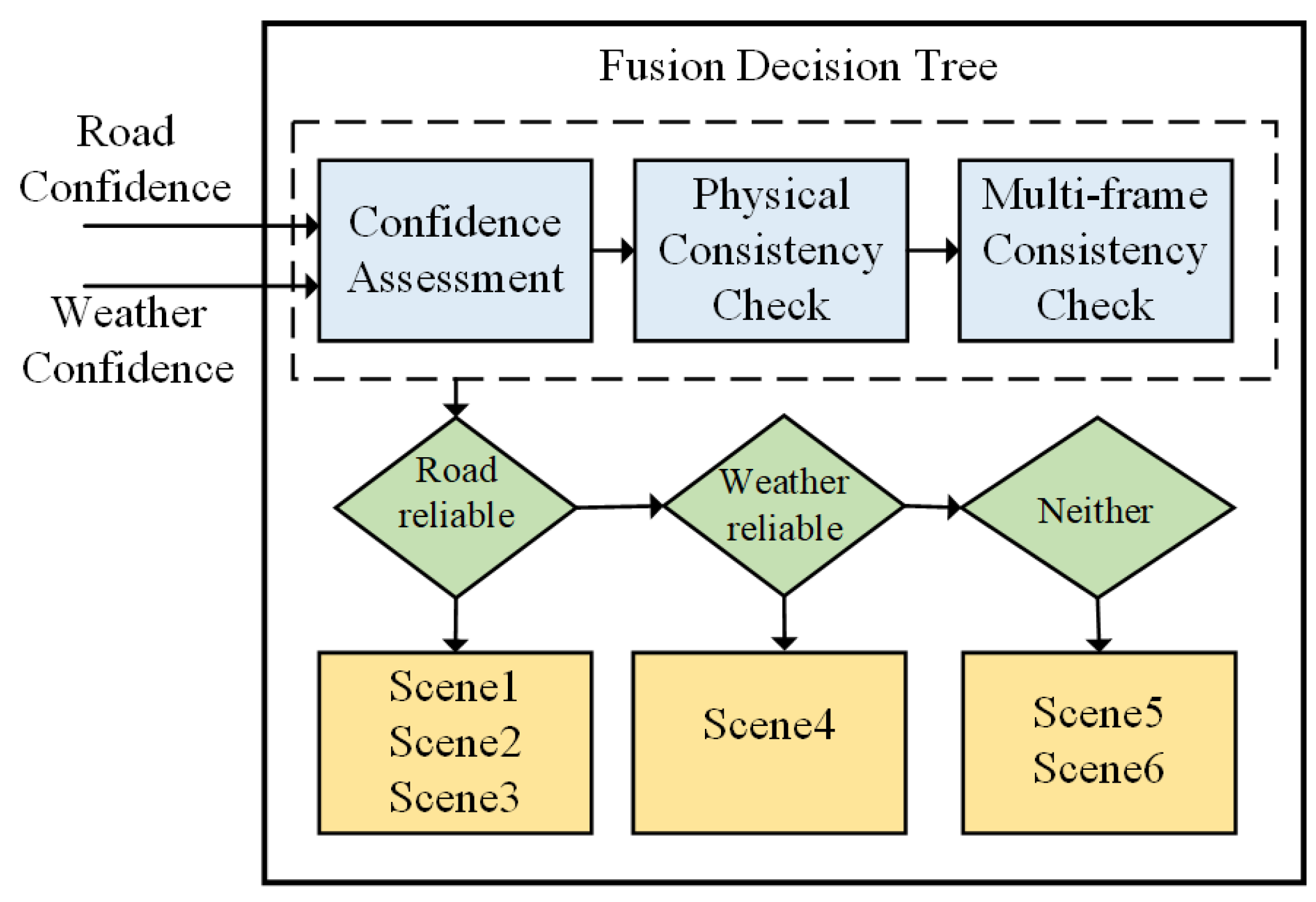

We propose a novel fusion strategy that accounts for uncertainties in both road and weather recognition. This approach enables reliable estimation even when the road type is unseen or recognition results are unreliable, significantly enhancing system robustness.

5. Conclusions

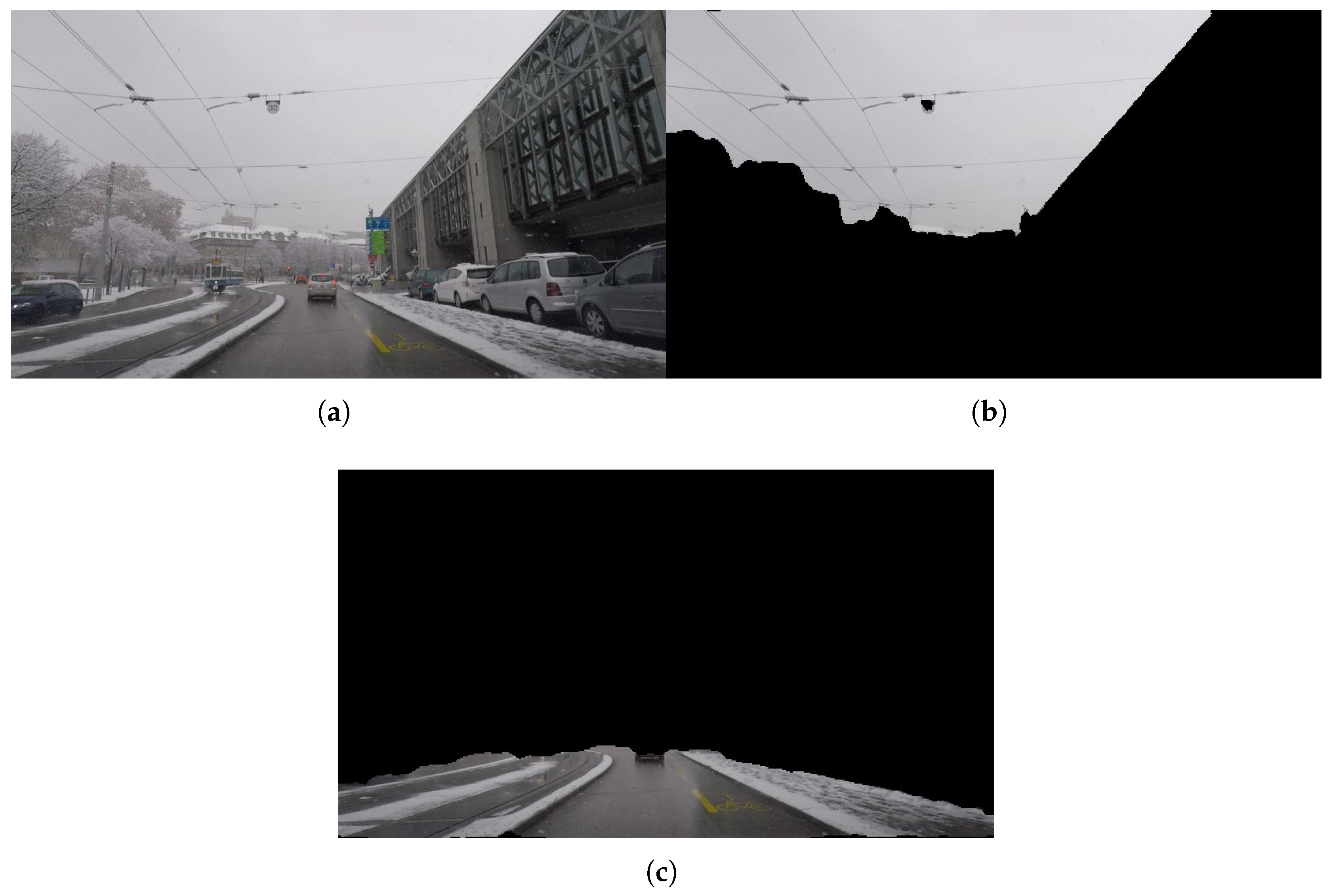

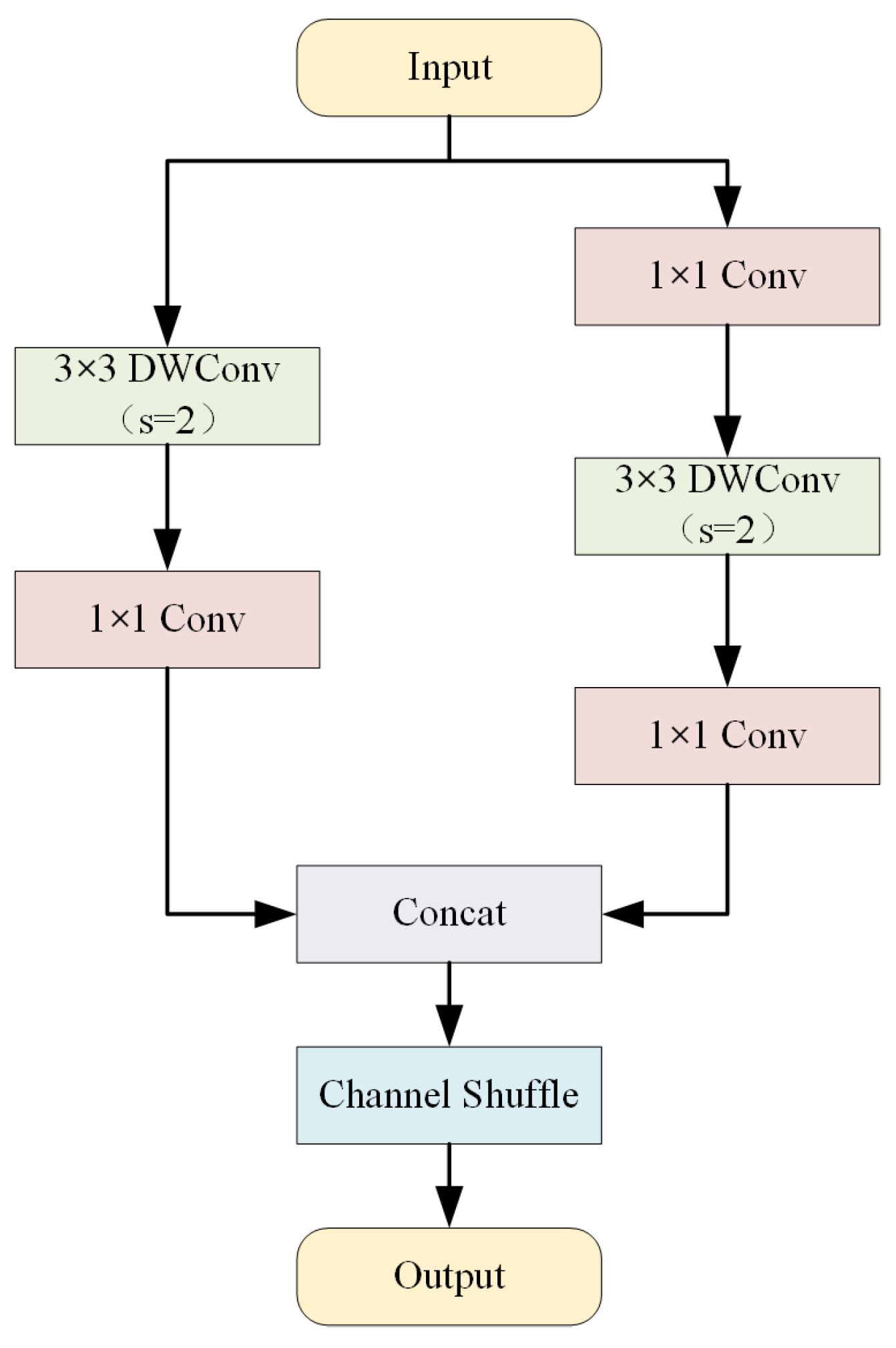

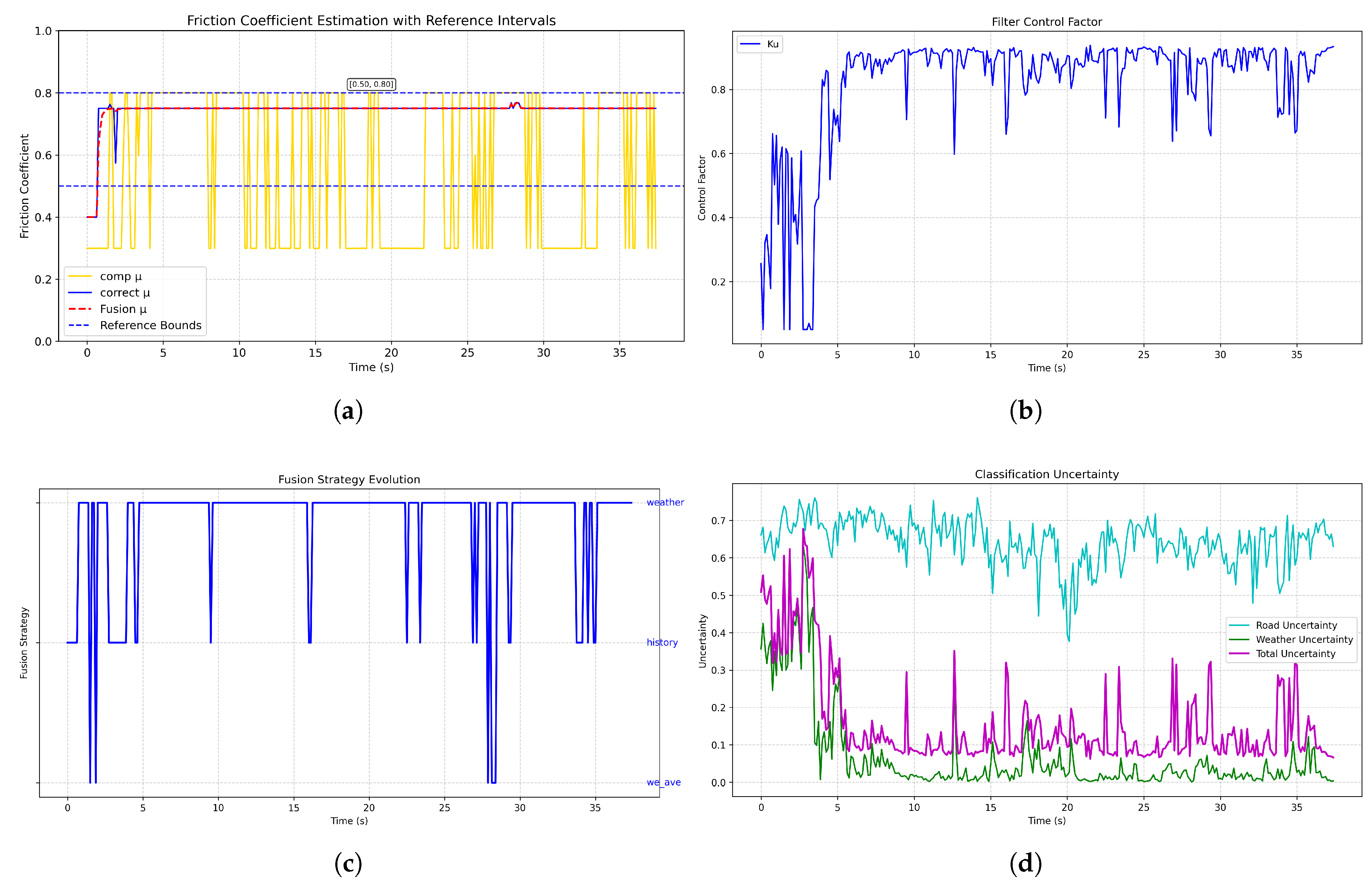

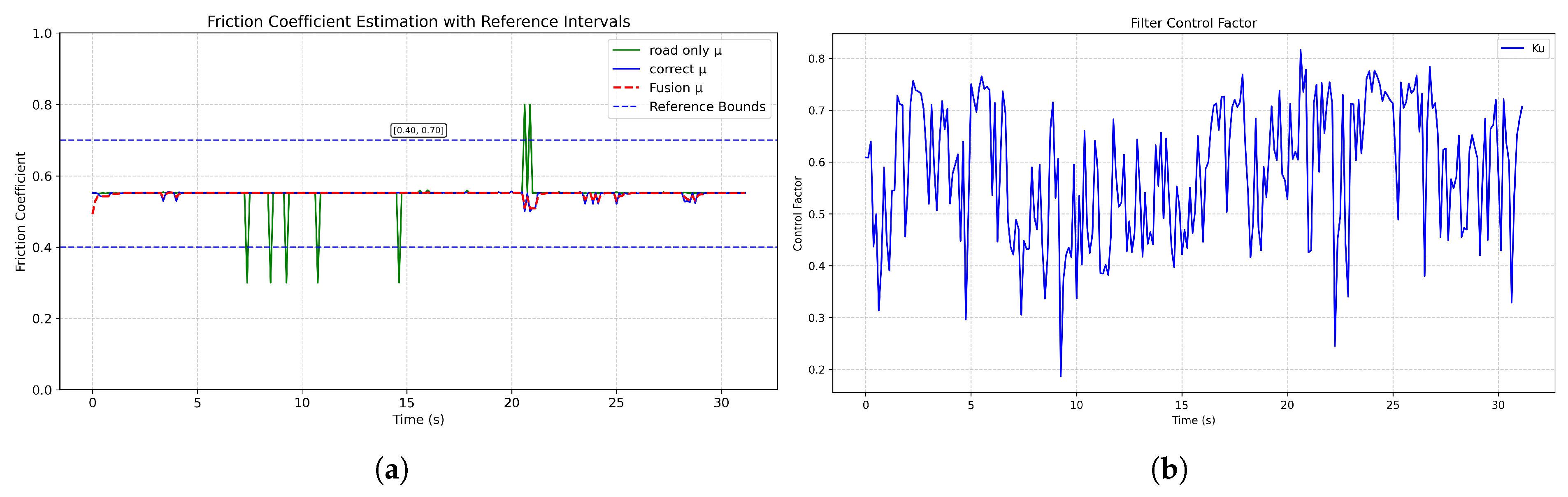

To address the poor generalization capability of vision-only methods in TRFC estimation, this paper proposes a novel TRFC estimation framework that fuses weather and road image information. By employing semantic segmentation to extract sky and road features separately, and incorporating an improved lightweight MobileNetV4 along with a three-branch convolutional network, the system achieves high-precision weather and road type recognition while maintaining computational efficiency. Furthermore, through a fusion decision tree and an uncertainty modeling mechanism, the system dynamically adjusts the estimation strategy to effectively handle conflicts or unreliable recognition results, significantly enhancing robustness and adaptability.

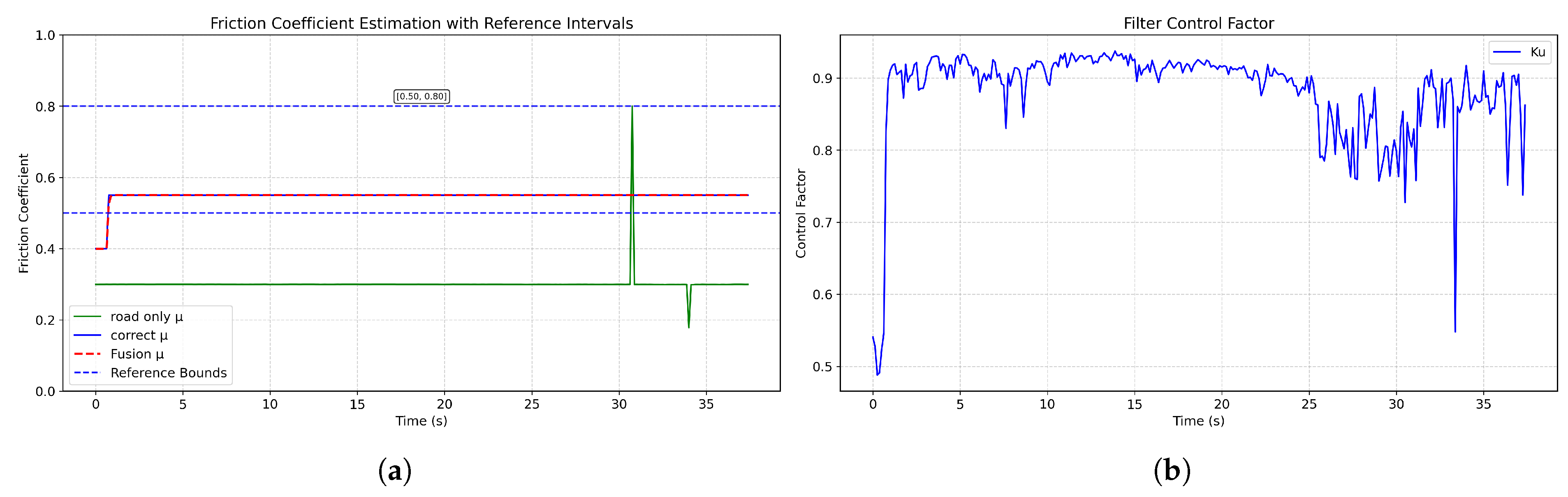

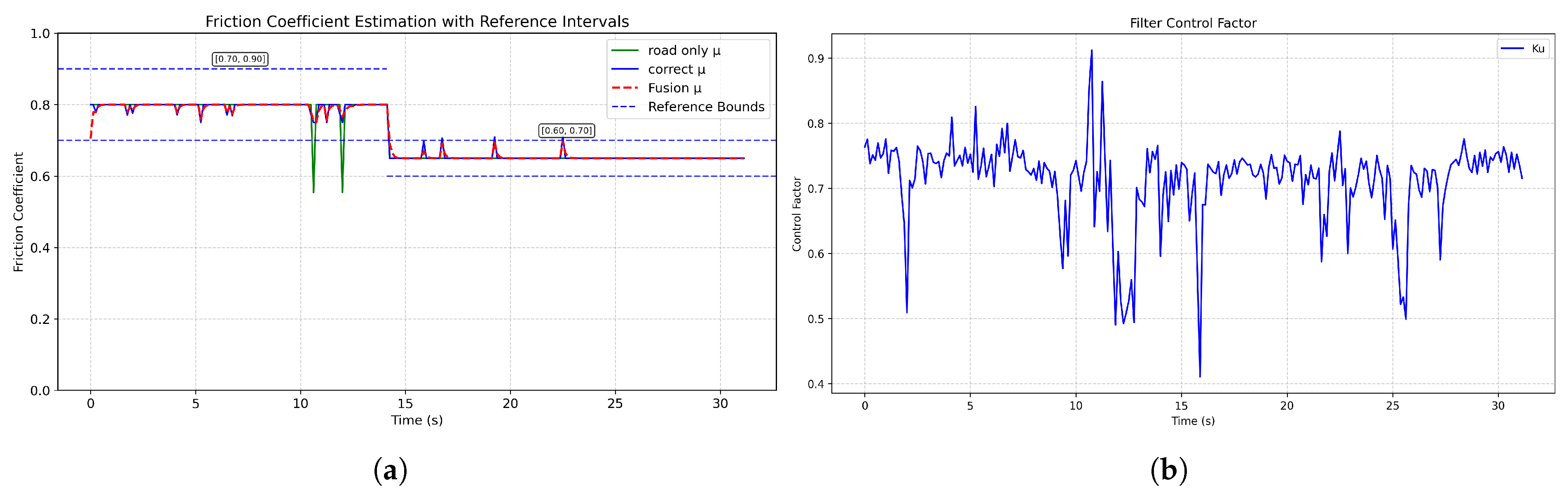

Ablation experiments demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed fusion method under various complex scenarios, including unknown road surfaces and transition roads. Compared to single-modality road recognition methods, the proposed approach significantly reduces estimation oscillation and improves convergence speed and stability, thereby providing more reliable environmental perception for intelligent driving systems.

Quantitatively, the proposed fusion method consistently delivers estimates that fall within physically plausible friction ranges and outperform vision-only baselines. As summarized in

Table 7, for the “Sunny Weather with Unknown Road Surface” scenario the method attains an in-range accuracy of 98.00%, a mean deviation of +0.0924, and an RMSE of 0.1049. For the “Fog Weather with Asphalt Road Surface” case it achieves 98.00% in-range accuracy, a mean deviation of −0.1031, and an RMSE of 0.1052. These results indicate that fusing weather information and applying uncertainty-aware filtering substantially improves estimation robustness in challenging and previously unseen conditions.

However, we also note some limitations. Under extreme low-visibility conditions (e.g., dense fog, night driving or dirty lens), visual signals may be insufficient to determine road surface details, which limits the attainable accuracy of TRFC estimates—a limitation common to vision-based methods.

Future work will focus on overcoming these limitations by integrating non-visual modalities (e.g., vehicle-dynamics modeling) and applying image-enhancement techniques (e.g., dehazing or thermal imaging) to achieve improved performance at minimal additional cost. These extensions are expected to further enhance TRFC estimation accuracy and provide better environmental perception for ADAS and AD systems.