Cardiovascular Disease Self-Management: Pilot Testing of an mHealth Healthy Eating Program

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

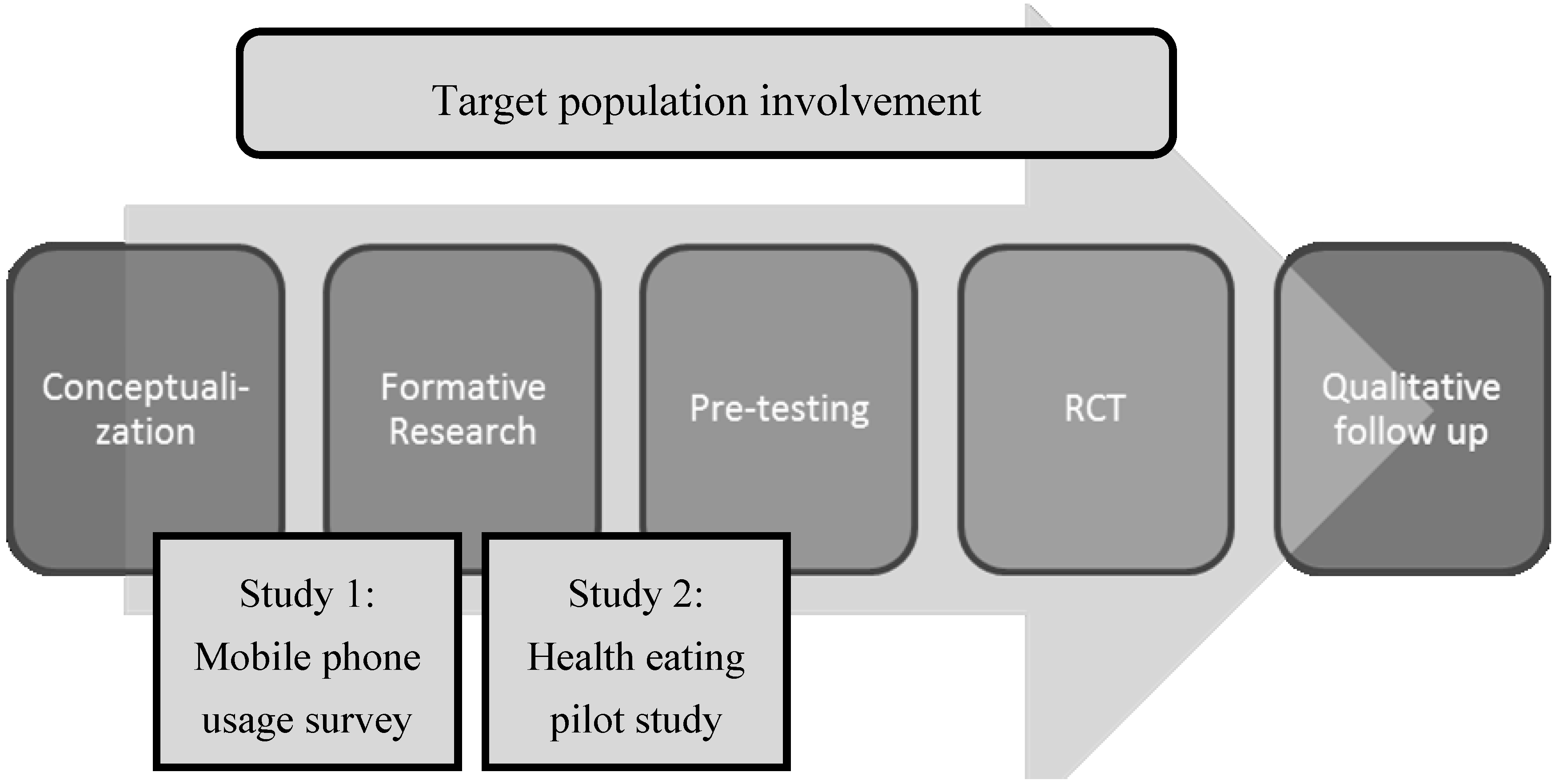

2.1. Overall Design

2.2. Step 1: Conceptualization

2.3. Step 2: Formative Research: Mobile Phone Usage among CR Participants across New Zealand

2.4. Step 3: Health Eating Pilot Study

- 1

- Text messages: A library of messages was developed providing participants with behavioral support to make healthy dietary changes and increase self-efficacy to change, revolving around a weekly theme (see Table 1 and Supplementary File 2). Mastery experiences, or building successful experiences [25], were created through messages encouraging goal setting and incorporating self-regulation skills to monitor progress to aid in achieving those goals. Social persuasion, or receiving verbal encouragement that one has the skills to succeed [25], was incorporated into the program through encouraging text messages.

Table 1. Example text messages. Theme Social cognitive theory construct Message Lowering my blood cholesterol Self-regulation Have you started to look at your nutrition labels?

Can you see how much total fat your packaged food contains?Choosing healthy meats and vegetarian alternatives Goal setting/Social persuasion Try replacing red meat with fish. Canned fish counts.

See if you can make this change twice this week. You can do it!Choosing healthy milk and milk products Mastery experience Small changes add up—ask the main shopper to switch from butter to a margarine blend. Less cost to your wallet and health! Packaged foods Outcome expectation Think you don’t have the willpower to avoid treat foods or takeaways? Think of your body, your mind, your family. - 2

- Role model video vignettes and educational Internet support: A library of brief video vignettes was developed to support vicarious learning, as people who observe role model behaviors and their favorable consequences are more likely to remember and repeat the behaviors endorsed by a model [25]. Cardiac patients (role models) were filmed discussing their experiences making dietary change. Brief cooking demonstrations and vignettes from dieticians and health professionals were also offered. Videos were viewed on a secure website where participants could set and review goals, view healthy recipes, meal ideas, and tips, and view links to other relevant web-based resources. The website was programmed to automatically release new content every three to four days, corresponding to the weekly theme.

2.5. Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Formative Research: Mobile Phone Usage

| Characteristic | Study 1 (n = 74) | Study 2 (n = 20) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 50 | 10 |

| Female | 24 | 10 |

| Age Group (in years) | ||

| ≤40 | 3 | 5 |

| 41–50 | 4 | 4 |

| 51–60 | 19 | 4 |

| 61–70 | 29 | 4 |

| 71–80 | 17 | 3 |

| ≥81 | 2 | 0 |

| Ethnicity a,b | ||

| New Zealand European | 50 | 14 |

| Māori | 16 | 2 |

| Pacific Islander | 0 | 3 |

| Other | 7 | 4 |

| Feature a | N = 74 (%) |

|---|---|

| Phone calls | 65 (88%) |

| Text messaging | 63 (85%) |

| Receive videos and/or photos | 17 (23%) |

| Internet search | 17 (23%) |

| Applications | 14 (19%) |

| Instant messaging | 5 (7%) |

| Social networks | 6 (8%) |

| Advice | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Healthy meal ideas and recipes | 47 (64%) |

| Practical ideas to manage stress | 40 (54%) |

| Setting goals | 19 (26%) |

| Steps to achieve goals | 20 (27%) |

| Exercise ideas | 48 (65%) |

| How to overcome cigarette cravings | 1 (1%) |

| How to remember to take your medications | 10 (14%) |

| Healthy eating tips for takeaways and dining out | 33 (45%) |

3.2. Pilot Testing: Healthy Eating Pilot Study

| Please rate the following according to whether you liked or disliked them | Liked | Disliked | No comment | Didn’t use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ideas on how to eat healthier | 19 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Information on the benefits of healthy eating | 18 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Information on cooking healthy meals | 16 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Receiving motivational messages | 15 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Being supported to feel like I could make these changes | 13 | 1 | 4 | 2 |

| Feeling like I belonged/like there were others going through the same thing as me | 11 | 1 | 6 | 2 |

| Receiving lots of text messages | 10 | 6 | 4 | 0 |

| The website | 10 | 1 | 3 | 6 |

| The time of day messages were sent | 9 | 2 | 9 | 0 |

| Seeing videos from health professionals | 9 | 0 | 2 | 9 |

| Being able to see ‘my goals’ on the website | 8 | 1 | 3 | 8 |

| Seeing videos from people like me | 4 | 0 | 6 | 10 |

- 1

- Text messaging was a convenient way to deliver healthy eating information. Participants felt that receiving texts was “quick and easy” and “non-invasive”. The content of the messages was “relevant”, “concise and interesting”.

- 2

- Texts were encouraging and an effective reminder to make informed healthy food choices. Participants felt the texts “encouraged and reminded me to make healthy choices”. The texts helped to serve “as alerts of what type of foods are good and are healthy substitutes”.

- 3

- I’d prefer a more personalized program. Seven participants commented on how to personalize the program, such as receiving feedback on their progress. Another suggestion was to tailor the time of day the messages were sent out, in order to send a relevant message at a time of day when people often struggled to make the healthy choice, such as “after dinner”. A few participants also mentioned they wanted some personal contact.

- 4

- Technical and time barriers prevented me from using the website. Three participants reported problems accessing the website; they forgot their password and revealed it wasn’t a priority to contact the research team for a new password. Some participants also commented that it was too time consuming to view the website, as they were “really busy at work” or “too tired to open the website again at home”.

HHESES

| Scale (Mean ± SD) | Pre-intervention | Post-intervention | Difference (Post–Pre) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heart healthy eating | 4.59 ± 53 | 4.76 ± 66 | 0.20 ± 55 |

| Environmental | 4.22 ± 71 | 4.83 ± 70 | 0.62 b ± 74 |

| Total self-efficacy a | 4.41 ± 59 | 4.79 ± 66 | 0.39 b ± 64 |

| Outcome expectancy | 5.22 ± 77 | 5.37 ± 82 | 0.15 ± 65 |

3.3. Discussion

Suggestions for Future Research

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Files

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jolliffe, J.; Rees, K.; Taylor, R.R.S.; Thompson, D.R.; Oldridge, N.; Ebrahim, S. Exercise-based rehabilitation for coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heran, B.S.; Chen, J.M.; Ebrahim, S.; Moxham, T.; Oldridge, N.; Rees, K.; Thompson, D.R.; Taylor, R.S. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2011, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bethell, H.J.N.; Lewin, R.J.; Dalal, H.M. Cardiac rehabilitation in the United Kingdom. Heart 2009, 95, 271–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doolan-Noble, F.; Broad, J.; Riddell, T.; North, D. Cardiac rehabilitation services in New Zealand: Access and utilisation. N. Z. Med. J. 2004, 117, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Suaya, J.A.; Shepard, D.S.; Normand, S.-L.T.; Ades, P.A.; Prottas, J.; Stason, W.B. Use of cardiac rehabilitation by medicare beneficiaries after myocardial infarction or coronary bypass surgery. Circulation 2007, 116, 1653–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjarnason-Wehrens, B.; McGee, H.; Zwisler, A.D.; Piepoli, M.F.; Benzer, W.; Schmid, J.P.; Dendale, P.; Pogosova, N.G.; Zdrenghea, D.; Niebauer, J.; et al. Cardiac rehabilitation in Europe: Results from the European cardiac rehabilitation inventory survey. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Prev. Rehabil. 2010, 17, 410–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.; Jolly, K.; Raftery, J.; Lip, G.Y.; Greenfield, S. “DNA” may not mean “did not participate”: A qualitative study of reasons for non-adherence at home- and centre-based cardiac rehabilitation. Fam. Pract. 2007, 24, 343–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfaeffli, L.; Maddison, R.; Whittaker, R.; Stewart, R.; Kerr, A.; Jiang, Y.; Kira, G.; Carter, K.; Dalleck, L.A. mHealth cardiac rehabilitation exercise intervention: Findings from content development studies. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2012, 12, e36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubeck, L.; Freedman, S.B.; Clark, A.M.; Briffa, T.; Bauman, A.; Redfern, J. Participating in cardiac rehabilitation: A systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative data. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2012, 19, 494–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchholz, S.W.; Wilbur, J.; Ingram, D.; Fogg, L. Physical activity text messaging interventions in adults: A systematic review. Worldviews Evid. Based Nurs. 2013, 10, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Telecommunication Union ICT Facts and Figures. Available online: http://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Documents/facts/ICTFactsFigures2013-e.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2013).

- Ofcom. Fixed-Line Voice and Mobile Connections Per Head: 2010. Available online: http://stakeholders.ofcom.org.uk/market-data-research/market-data/communications-market-reports/cmr11/international/icmr-1.08/ (accessed on 23 May 2012).

- Commerce Commission New Zealand. Annual Telecommunications Monitoring Report 2011. Available online: http://www.nbr.co.nz/sites/default/files/images/2011-Annual-Telecommunications-Market-Monitoring-Report-30-April-2012.pdf (accessed on 23 May 2012).

- International Telecommunication Union. Measuring the Information Society 2011. Available online: http://www.itu.int/ITU-D/ict/publications/idi/material/2011/MIS2011-ExceSum-E.pdf (accessed on 25 June 2012).

- Parker, S.J.; Jessel, S.; Richardson, J.E.; Reid, M.C. Older adults are mobile too! Identifying the barriers and facilitators to older adults’ use of mHealth for pain management. BMC Geriatr. 2013, 13, e43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, J.; Allen, J. Mobile Phone interventions to increase physical activity and reduce weight: A systematic review. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2013, 28, 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, S.; Boren, S.; Balas, E. Healthcare via cell phones: A systematic review. Telemed. e-Health 2009, 15, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole-Lewis, H.; Kershaw, T. Text messaging as a tool for behavior change in disease prevention and management. Epidemiol. Rev. 2010, 32, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fjeldsoe, B.S.; Marshall, A.L.; Miller, Y.D. Behavior change interventions delivered by mobile phone telephone short-message service. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2009, 36, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddison, R.; Whittaker, R.; Stewart, R.; Kerr, A.J.; Jiang, A.; Kira, G.; Carter, K.H.; Pfaeffli, L. HEART: Heart exercise and remote technologies: A randomized controlled trial study protocol. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, K.; Maddison, R.; Whittaker, R.; Stewart, R.; Kerr, A.; Jiang, Y.; Pfaeffli, L.; Rawstorn, J. Heart: Efficacy of a mHealth exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation program. Heart Lung Circ. 2013, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittaker, R.; Merry, S.; Dorey, E.; Maddison, R. A Development and evaluation process for mHealth interventions: Examples from New Zealand. J. Health Commun. 2012, 17, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittaker, R.; Dorey, E.; Bramley, D.; Bullen, C.; Denny, S.; Elley, R.; Maddison, R.; McRobbie, H.; Parag, V.; Rodgers, A.; et al. A theory-based video messaging mobile phone intervention for smoking cessation: Randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2011, 13, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- New Zealand Guidelines Group. Evidence-Based Best Practice Guideline: Cardiac Rehabilitation 2002. Available online: http://www.health.govt.nz/publication/cardiac-rehabilitation-guideline/ (accessed on 6 January 2014).

- Bandura, A. Health promotion from the perspective of social cognitive theory. Psychol. Health 1998, 13, 623–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, P.B.; Salyer, J. Self-efficacy and barriers to healthy diet in cardiac rehabilitation participants and nonparticipants. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2012, 27, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thabane, L.; Ma, J.; Chu, R.; Cheng, J.; Ismaila, A.; Rios, L.P.; Robson, R.; Thabane, M.; Giangregorio, L.; Goldsmith, C.H. A tutorial on pilot studies: The what, why and how. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2010, 10, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaughan, M.E. Heart healthy eating self-efficacy: An effective tool for managing eating behavior change interventions for hypercholesterolemia. Top. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 18, 229–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LimeSurvey Project Team. LimeSurvey: An Open Source Survey Tool 2012. Available online: http://www.limesurvey.org/ (accessed on 6 January 2014).

- Thomas, D.R. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. Am. J. Eval. 2006, 27, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofcom. Adults Media Use and Attitudes Report: 2012. Available online: http://stakeholders.ofcom.org.uk/market-data-research/media-literacy/archive/medlitpub/medlitpubrss/adults-media-use-attitudes/ (accessed on 7 June 2012).

- Norman, G.J.; Zabinski, M.F.; Adams, M.A.; Rosenberg, D.E.; Yaroch, A.L.; Atienza, A.A. A review of eHealth interventions for physical activity and dietary behavior change. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2007, 33, 336–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ. Behav. 2004, 31, 143–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, W.; Rivera, D.; Atienza, A.; Nilsen, W.; Allison, S.; Mermelstein, R. Health behavior models in the age of mobile interventions: Are our theories up to the task? Transl. Behav. Med. 2011, 1, 53–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klasnja, P.; Pratt, W. Healthcare in the pocket: Mapping the space of mobile-phone health interventions. J. Biomed. Inform. 2012, 45, 184–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Free, C.; Phillips, G.; Galli, L.; Watson, L.; Felix, L.; Edwards, P.; Patel, V.; Haines, A. The effectiveness of mobile-health technology-based health behaviour change or disease management interventions for health care consumers: A systematic review. PLoS Med. 2013, 10, e1001362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Dale, L.P.; Whittaker, R.; Eyles, H.; Mhurchu, C.N.; Ball, K.; Smith, N.; Maddison, R. Cardiovascular Disease Self-Management: Pilot Testing of an mHealth Healthy Eating Program. J. Pers. Med. 2014, 4, 88-101. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm4010088

Dale LP, Whittaker R, Eyles H, Mhurchu CN, Ball K, Smith N, Maddison R. Cardiovascular Disease Self-Management: Pilot Testing of an mHealth Healthy Eating Program. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2014; 4(1):88-101. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm4010088

Chicago/Turabian StyleDale, Leila Pfaeffli, Robyn Whittaker, Helen Eyles, Cliona Ni Mhurchu, Kylie Ball, Natasha Smith, and Ralph Maddison. 2014. "Cardiovascular Disease Self-Management: Pilot Testing of an mHealth Healthy Eating Program" Journal of Personalized Medicine 4, no. 1: 88-101. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm4010088

APA StyleDale, L. P., Whittaker, R., Eyles, H., Mhurchu, C. N., Ball, K., Smith, N., & Maddison, R. (2014). Cardiovascular Disease Self-Management: Pilot Testing of an mHealth Healthy Eating Program. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 4(1), 88-101. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm4010088