Neurological Complications After Thoracic Endovascular Repair (TEVAR): A Narrative Review of the Incidence, Mechanisms and Strategies for Prevention and Management

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Overview of Neurological Complications After TEVAR

3.1. Cerebrovascular Events After TEVAR

3.2. Spinal Cord Ischemia After TEVAR

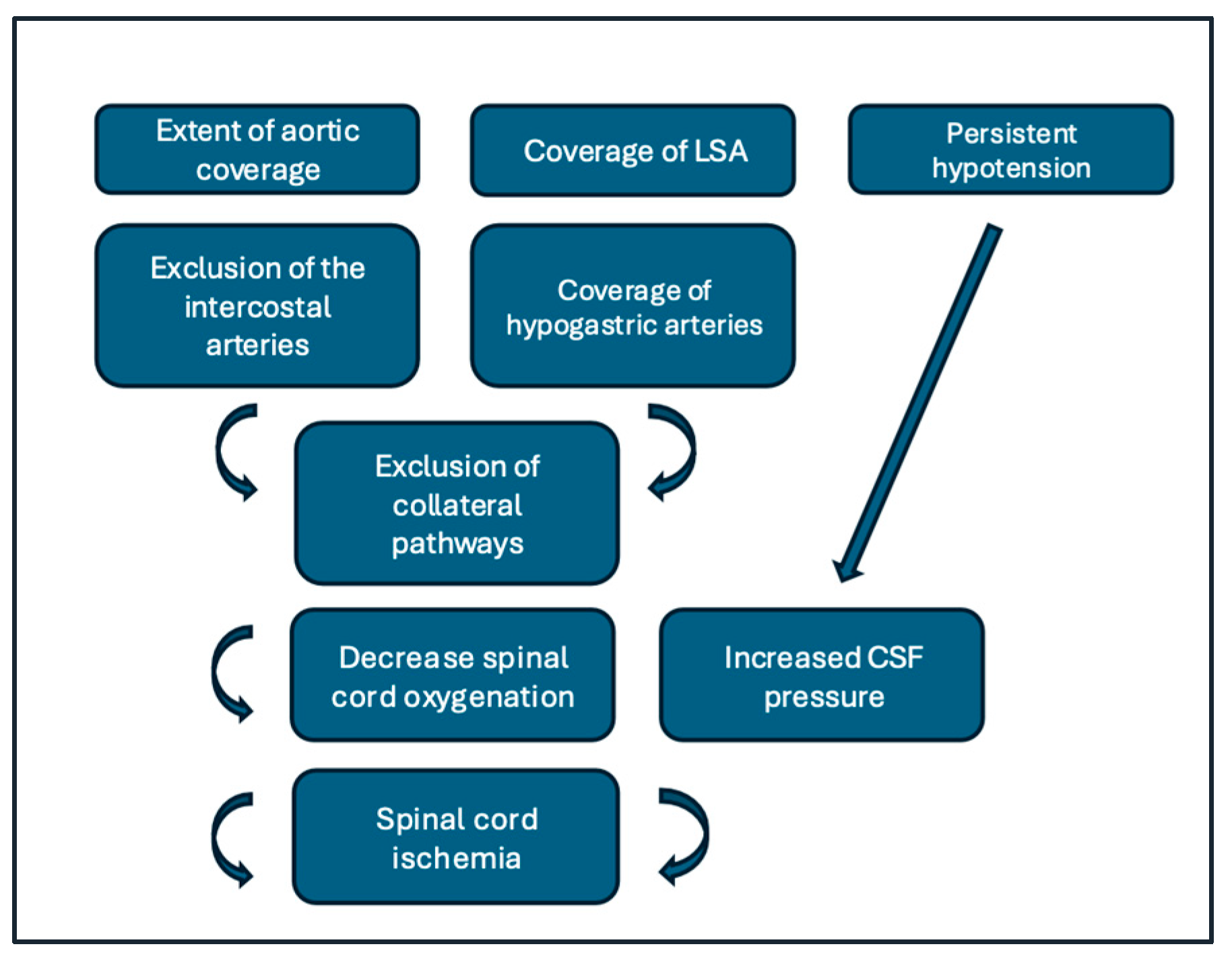

3.2.1. Pathophysiology

3.2.2. Incidence, Outcomes, and Prognosis

3.2.3. Risk Factors

3.2.4. Prevention Strategies

3.2.5. Management of Established Spinal Cord Ischemia (SCI)

3.3. Delirium and Cognitive Outcomes

- Preoperative cognitive screening (e.g., MoCA or other validated tools) to identify high-risk patients who may benefit from closer monitoring and targeted prevention.

- Optimization of modifiable risk factors, such as correction of hyponatremia and other electrolyte disturbances, meticulous management of renal function, and avoidance of unnecessary benzodiazepines and anticholinergic agents [54].

- Implementation of a multimodal delirium-prevention bundle, comprising orientation aids, preservation of circadian rhythm and sleep, early mobilization, adequate pain control with opioid-sparing strategies.

3.4. Other Neurological Complications

4. Gaps in Knowledge and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TEVAR | Thoracic Endovascular Aortic Repair |

| SCI | Spinal Cord Ischemia |

| LSA | Left Subclavian Artery |

| CSF | Cerebro Spinal Fluid |

| CTa | Computed Tomography Angiography |

| ASA | Anterior Spinal Artery |

| AKA | Adamkiewicz Artery |

| EVAR | Endovascular Aortic Repair |

| MAP | Mean Arterial Pressure |

| VQI | Vascular Quality Initiative |

| LIMA | Left Internal Mammary Artery |

| MIS2ACE | Minimally Invasive Segmental Artery Coil Embolization |

| CSFD | Cerebro Spinal Fluid Drainage |

| SCPP | Spinal Cord Perfusion Pressure |

| F/B EVAR | Fenestrated/Branch Endovascular Aortic Repair |

| SSEPs | Somatosensory Evoked Potentials |

| MEPs | Motor Evoked Potentials |

| POD | Postoperative Delirium |

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| MoCA | Montreal Cognitive Assessment |

| PRES | Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| CES | Cholesterol Embolization Syndrome |

References

- Chen, S.W.; Lee, K.B.; Napolitano, M.A.; Murillo-Berlioz, A.E.; Sattah, A.P.; Sarin, S.; Trachiotis, G. Complications and Management of the Thoracic Endovascular Aortic Repair. Aorta 2020, 8, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piazza, M.; Squizzato, F.; Milan, L.; Miccoli, T.; Grego, F.; Antonello, M. Incidence and Predictors of Neurological Complications Following Thoracic Endovascular Aneurysm Repair in the Global Registry for Endovascular Aortic Treatment. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2019, 58, 512–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scali, S.T.; Giles, K.A.; Wang, G.J.; Kubilis, P.; Neal, D.; Huber, T.S.; Upchurch, G.R.; Siracuse, J.J.; Shutze, W.P.; Beck, A.W. National Incidence, Mortality Outcomes, and Predictors of Spinal Cord Ischemia after Thoracic Endovascular Aortic Repair. J. Vasc. Surg. 2020, 72, 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rinaldi, E.; Loschi, D.; Favia, N.; Santoro, A.; Chiesa, R.; Melissano, G. Spinal Cord Ischemia in Open and Endovascular Aortic Repair. Aorta 2022, 10, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, S.K.; Mahapatra, R.P.; Barik, R.; Acharya, D.; Panda, D.; Malla, S.R.; Karthik Kowtarapu, S.; Mohanan, S.P.; Singh, P.K. Paraplegia Following Thoracic Endovascular Aneurysm Repair. JACC Case Rep. 2025, 30, 105071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullery, B.W.; Wang, G.J.; Low, D.; Cheung, A.T. Neurological Complications of Thoracic Endovascular Aortic Repair. Semin. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2011, 15, 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, R.A.; Ozdemir, B.A.; Matthews, D.; Loftus, I.M. A Systematic Review of Postoperative Cognitive Decline Following Open and Endovascular Aortic Aneurysm Surgery. Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl. 2017, 99, 97–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houghton, J.S.M.; Nickinson, A.T.O.; Bridgwood, B.; Nduwayo, S.; Pepper, C.J.; Rayt, H.S.; Gray, L.J.; Haunton, V.J.; Sayers, R.D. Prevalence of Cognitive Impairment in Individuals with Vascular Surgical Pathology: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2021, 61, 664–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaolanis, G.I.; Antonopoulos, C.N.; Charbonneau, P.; Georgakarakos, E.; Moris, D.; Scali, S.; Kotelis, D.; Donas, K. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Stroke Rates in Patients Undergoing Thoracic Endovascular Aortic Repair for Descending Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm and Type B Dissection. J. Vasc. Surg. 2022, 76, 292–301.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanos, K.; Kellert, L.; Rantner, B.; Banafsche, R.; Tsilimparis, N. The Importance of Definitions and Reporting Standards for Cerebrovascular Events After Thoracic Endovascular Aortic Repair. J. Endovasc. Ther. 2018, 25, 737–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Allmen, R.S.; Gahl, B.; Powell, J.T. Editor’s Choice—Incidence of Stroke Following Thoracic Endovascular Aortic Repair for Descending Aortic Aneurysm: A Systematic Review of the Literature with Meta-Analysis. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2017, 53, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piazza, M.; Squizzato, F.; Ferri, M.; Pratesi, G.; Gatta, E.; Orrico, M.; Giudice, R.; Antonello, M.; Antonello, M.; Piazza, M.; et al. Outcomes of Off-the-Shelf Preloaded Inner Branch Device for Urgent Endovascular Thoraco-Abdominal Aortic Repair in the ItaliaN Branched Registry of E-Nside EnDograft. J. Vasc. Surg. 2024, 80, 1350–1360.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiBartolomeo, A.D.; Ding, L.; Weaver, F.A.; Han, S.M.; Magee, G.A. Risk of Stroke with Thoracic Endovascular Aortic Repair of the Aortic Arch. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2023, 97, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.D.; Chia, M.C.; Eskandari, M.K. Thoracic Endovascular Aortic Repair with Supra-Aortic Trunk Revascularization Is Associated with Increased Risk of Periprocedural Ischemic Stroke. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2022, 87, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riambau, V.; Böckler, D.; Brunkwall, J.; Cao, P.; Chiesa, R.; Coppi, G.; Czerny, M.; Fraedrich, G.; Haulon, S.; Jacobs, M.J.; et al. Editor’s Choice—Management of Descending Thoracic Aorta Diseases. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2017, 53, 4–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Marco, L.; Nocera, C.; Buia, F.; Campanini, F.; Attinà, D.; Murana, G.; Lovato, L.; Pacini, D. Total Endovascular Arch Repair: Initial Experience in Bologna. JTCVS Tech. 2024, 28, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lescan, M. New Insights into Ischaemic Complications after Thoracic Endovascular Aneurysm Repair. Eur. J. Cardio-Thorac. Surg. 2023, 64, ezad264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presta, V.; Figliuzzi, I.; Citoni, B.; Miceli, F.; Battistoni, A.; Musumeci, M.B.; Coluccia, R.; De Biase, L.; Ferrucci, A.; Volpe, M.; et al. Effects of Different Statin Types and Dosages on Systolic/Diastolic Blood Pressure: Retrospective Analysis of 24-hour Ambulatory Blood Pressure Database. J. Clin. Hypertens. 2018, 20, 967–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griepp, E.B.; Di Luozzo, G.; Schray, D.; Stefanovic, A.; Geisbüsch, S.; Griepp, R.B. The Anatomy of the Spinal Cord Collateral Circulation. Ann. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2012, 1, 350–357. [Google Scholar]

- Seike, Y.; Nishii, T.; Yoshida, K.; Yokawa, K.; Masada, K.; Inoue, Y.; Fukuda, T.; Matsuda, H. Covering the Intercostal Artery Branching of the Adamkiewicz Artery during Endovascular Aortic Repair Increases the Risk of Spinal Cord Ischemia. JTCVS Open 2024, 17, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etz, C.D.; Kari, F.A.; Mueller, C.S.; Silovitz, D.; Brenner, R.M.; Lin, H.-M.; Griepp, R.B. The Collateral Network Concept: A Reassessment of the Anatomy of Spinal Cord Perfusion. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2011, 141, 1020–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, D.; Narsinh, K. Editorial. The Relevance of the Artery of Adamkiewicz in the 21st Century. J. Neurosurg. Spine 2023, 38, 230–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohira, S.; Lansman, S.L.; Spielvogel, D. Collateral Network Concept in 2023. Ann. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2023, 12, 450–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaudino, M.; Khan, F.M.; Rahouma, M.; Naik, A.; Hameed, I.; Spadaccio, C.; Robinson, N.B.; Ruan, Y.; Demetres, M.; Oakley, C.T.; et al. Spinal Cord Injury after Open and Endovascular Repair of Descending Thoracic and Thoracoabdominal Aortic Aneurysms: A Meta-Analysis. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2022, 163, 552–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzghari, T.; An, K.R.; Harik, L.; Rahouma, M.; Dimagli, A.; Perezgorvas-Olaria, R.; Demetres, M.; Cancelli, G.; Soletti, G., Jr.; Lau, C.; et al. Spinal Cord Injury after Open and Endovascular Repair of Descending Thoracic Aneurysm and Thoracoabdominal Aortic Aneurysm: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ann. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2023, 12, 409–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brisard, L.; El Batti, S.; Borghese, O.; Maurel, B. Risk Factors for Spinal Cord Injury during Endovascular Repair of Thoracoabdominal Aneurysm: Review of the Literature and Proposal of a Prognostic Score. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 7520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lella, S.K.; Waller, H.D.; Pendleton, A.; Latz, C.A.; Boitano, L.T.; Dua, A. A Systematic Review of Spinal Cord Ischemia Prevention and Management after Open and Endovascular Aortic Repair. J. Vasc. Surg. 2022, 75, 1091–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torre, D.E.; Pirri, C. Spinal Cord Protection in Open and Endovascular Aortic Surgery: Current Strategies, Controversies and Future Directions. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2025, 12, 1671350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aucoin, V.J.; Motyl, C.M.; Novak, Z.; Eagleton, M.J.; Farber, M.A.; Gasper, W.; Oderich, G.S.; Mendes, B.; Schanzer, A.; Tenorio, E.; et al. Predictors and Outcomes of Spinal Cord Injury Following Complex Branched/Fenestrated Endovascular Aortic Repair in the US Aortic Research Consortium. J. Vasc. Surg. 2023, 77, 1578–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSart, K.; Scali, S.T.; Feezor, R.J.; Hong, M.; Hess, P.J.; Beaver, T.M.; Huber, T.S.; Beck, A.W. Fate of Patients with Spinal Cord Ischemia Complicating Thoracic Endovascular Aortic Repair. J. Vasc. Surg. 2013, 58, 635–642.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sufali, G.; Faggioli, G.; Gallitto, E.; Pini, R.; Vacirca, A.; Mascoli, C.; Gargiulo, M. Results of a Multidisciplinary Spinal Cord Ischemia Prevention Protocol in Elective Repair of Crawford’s Extent I-III Thoracoabdominal Aneurysm by Fenestrated and Branched Endografts. Vessel Plus 2024, 8, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feezor, R.J.; Martin, T.D.; Hess, P.J.; Daniels, M.J.; Beaver, T.M.; Klodell, C.T.; Lee, W.A. Extent of Aortic Coverage and Incidence of Spinal Cord Ischemia After Thoracic Endovascular Aneurysm Repair. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2008, 86, 1809–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisdas, T.; Panuccio, G.; Sugimoto, M.; Torsello, G.; Austermann, M. Risk Factors for Spinal Cord Ischemia after Endovascular Repair of Thoracoabdominal Aortic Aneurysms. J. Vasc. Surg. 2015, 61, 1408–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuozzo, S.; Martinelli, O.; Brizzi, V.; Miceli, F.; Flora, F.; Sbarigia, E.; Gattuso, R. Early Experience with Ovation Alto Stent-Graft. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2023, 88, 346–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinelli, O.; Cuozzo, S.; Miceli, F.; Gattuso, R.; D’Andrea, V.; Sapienza, P.; Bellini, M.I. Elective Endovascular Aneurysm Repair (EVAR) for the Treatment of Infrarenal Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms of 5.0–5.5 cm: Differences between Men and Women. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 4364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xodo, A.; D’Oria, M.; Mendes, B.; Bertoglio, L.; Mani, K.; Gargiulo, M.; Budtz-Lilly, J.; Antonello, M.; Veraldi, G.F.; Pilon, F.; et al. Peri-Operative Management of Patients Undergoing Fenestrated-Branched Endovascular Repair for Juxtarenal, Pararenal and Thoracoabdominal Aortic Aneurysms: Preventing, Recognizing and Treating Complications to Improve Clinical Outcomes. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiraoka, T.; Komiya, T.; Tsuneyoshi, H.; Shimamoto, T. Risk Factors for Spinal Cord Ischaemia after Thoracic Endovascular Aortic Repair. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2018, 27, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, H.A.; Ding, L.; Han, S.M.; Fleischman, F.; Weaver, F.A.; Magee, G.A. Spinal Cord Ischemia and Reinterventions Following Thoracic Endovascular Repair for Acute Type B Aortic Dissections. J. Vasc. Surg. 2024, 80, 656–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doering, A.; Nana, P.; Torrealba, J.I.; Panuccio, G.; Trepte, C.; Chindris, V.; Kölbel, T. Intra- and Early Post-Operative Factors Affecting Spinal Cord Ischemia in Patients Undergoing Fenestrated and Branched Endovascular Aortic Repair. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 3978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidemann, F.; Tsilimparis, N.; Rohlffs, F.; Debus, E.S.; Larena-Avellaneda, A.; Wipper, S.; Kölbel, T. Staged Procedures for Prevention of Spinal Cord Ischemia in Endovascular Aortic Surgery. Gefasschirurgie 2018, 23, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branzan, D.; Etz, C.D.; Moche, M.; Von Aspern, K.; Staab, H.; Fuchs, J.; Then Bergh, F.; Scheinert, D.; Schmidt, A. Ischaemic Preconditioning of the Spinal Cord to Prevent Spinal Cord Ischaemia during Endovascular Repair of Thoracoabdominal Aortic Aneurysm: First Clinical Experience. EuroIntervention 2018, 14, 828–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brotis, A.G.; Kalogeras, A.; Bareka, M.; Arnaoutoglou, E.; Spanos, K.; Matsagkas, M.; Fountas, K.N. Prevention and Management of Spinal Cord Ischemia after Aortic Surgery: An Umbrella Review. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aucoin, V.J.; Bolaji, B.; Novak, Z.; Spangler, E.L.; Sutzko, D.C.; McFarland, G.E.; Pearce, B.J.; Passman, M.A.; Scali, S.T.; Beck, A.W. Trends in the Use of Cerebrospinal Drains and Outcomes Related to Spinal Cord Ischemia after Thoracic Endovascular Aortic Repair and Complex Endovascular Aortic Repair in the Vascular Quality Initiative Database. J. Vasc. Surg. 2021, 74, 1067–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sickels, A.D.; Novak, Z.; Scali, S.T.; St. John, R.; Pearce, B.J.; Rowse, J.W.; Beck, A.W. A Prevention Protocol Reduces Spinal Cord Ischemia in Patients Undergoing Branched/Fenestrated Endovascular Aortic Repair. J. Vasc. Surg. 2025, 81, 29–37.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosvall, L.; Karelis, A.; Sonesson, B.; Dias, N.V. A Dedicated Preventive Protocol Sustainably Avoids Spinal Cord Ischemia after Endovascular Aortic Repair. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2024, 11, 1440674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenorio, E.R.; Oderich, G.S. Spinal Cord Protection: Lessons Learned from Endovascular Repair. Ann. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2023, 12, 484–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Eisenberg, N.; Beaton, D.; Lee, D.S.; Aljabri, B.; Al-Omran, L.; Wijeysundera, D.N.; Rotstein, O.D.; Lindsay, T.F.; de Mestral, C.; et al. Using Machine Learning to Predict Outcomes Following Thoracic and Complex Endovascular Aortic Aneurysm Repair. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2025, 14, e039221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rijken, L.; Zwetsloot, S.; Smorenburg, S.; Wolterink, J.; Išgum, I.; Marquering, H.; van Duivenvoorde, J.; Ploem, C.; Jessen, R.; Catarinella, F.; et al. Developing Trustworthy Artificial Intelligence Models to Predict Vascular Disease Progression: The VASCUL-AID-RETRO Study Protocol. J. Endovasc. Ther. 2025, 15266028251313963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasiah, M.G.; Konings, T.J.; Nio, A.; Moriconi, S.; Patel, A.S.; Smith, A.; Abdelhalim, M.A.; Delhaas, T.; Cardoso, M.J.; Lamata, P.; et al. In Silico Modelling of Changes in Spinal Cord Blood Flow after Endovascular Aortic Aneurysm Repair. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2512.10048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellauzi, H.; Arora, H.; Elefteriades, J.A.; Zaffar, M.A.; Ellauzi, R.; Popescu, W.M. Cerebrospinal Fluid Drainage for Prevention of Spinal Cord Ischemia in Thoracic Endovascular Aortic Surgery—Pros and Cons. AORTA 2022, 10, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spratt, J.R.; Walker, K.L.; Neal, D.; Arnaoutakis, G.J.; Martin, T.D.; Back, M.R.; Zasimovich, Y.; Franklin, M.; Shahid, Z.; Upchurch, G.R.; et al. Rescue Therapy for Symptomatic Spinal Cord Ischemia after Thoracic Endovascular Aortic Repair. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2024, 168, 15–25.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzolai, L.; Teixido-Tura, G.; Lanzi, S.; Boc, V.; Bossone, E.; Brodmann, M.; Bura-Rivière, A.; De Backer, J.; Deglise, S.; Della Corte, A.; et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the Management of Peripheral Arterial and Aortic Diseases. Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, 3538–3700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanhainen, A.; Van Herzeele, I.; Bastos Goncalves, F.; Bellmunt Montoya, S.; Berard, X.; Boyle, J.R.; D’Oria, M.; Prendes, C.F.; Karkos, C.D.; Kazimierczak, A.; et al. Editor’s Choice—European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) 2024 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management of Abdominal Aorto-Iliac Artery Aneurysms. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2024, 67, 192–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Yang, F.; Luo, S.; Li, C.; Liu, W.; Liu, Y.; Huang, W.; Xie, E.; Chen, L.; Su, S.; et al. Incidence, Predictors and Outcomes of Delirium in Complicated Type B Aortic Dissection Patients After Thoracic Endovascular Aortic Repair. Clin. Interv. Aging 2021, 16, 1581–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, C.; Huang, H.; Wang, H.; Mao, J. Development and Validation of a Nomogram to Predict Postoperative Delirium in Type B Aortic Dissection Patients Underwent Thoracic Endovascular Aortic Repair. Front. Surg. 2022, 9, 986185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, T.; Zhao, C.; Lin, D. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Risk Factors for Postoperative Delirium in Patients with Acute Type A Aortic Dissection. J. Thorac. Dis. 2023, 15, 668–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhang, L.; Tang, W.; Zhao, S.; Li, M.; Li, J.; Shao, Y. A Nomogram for Predicting the Risk of Postoperative Delirium in Individuals Undergoing Cardiovascular Surgery. Eur. J. Neurol. 2024, 31, e16483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, H.; Liao, G.; Ye, B.; Wen, M.; Li, J. Establishment and Validation of a Nomogram of Postoperative Delirium in Patients Undergoing Cardiac Surgery: A Retrospective Study of MIMIC-IV. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2025, 25, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Meng, Y.; Qian, X.; Wu, H.; Liu, Y.; Ji, P.; Chen, H. Prediction Model for Delirium in Patients with Cardiovascular Surgery: Development and Validation. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2022, 17, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodijk, D.; Banning, L.B.D.; Te Velde-Keyzer, C.A.; van Munster, B.C.; Bakker, S.J.L.; van Leeuwen, B.L.; Zeebregts, C.J.; Pol, R.A. Preoperative Cognitive Performance and Its Association with Postoperative Complications in Vascular Surgery Patients: A Prospective Study. Am. J. Surg. 2025, 239, 115784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Styra, R.; Larsen, E.; Dimas, M.A.; Baston, D.; Elgie-Watson, J.; Flockhart, L.; Lindsay, T.F. The Effect of Preoperative Cognitive Impairment and Type of Vascular Surgery Procedure on Postoperative Delirium with Associated Cost Implications. J. Vasc. Surg. 2019, 69, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janczak, D.; Ziomek, A.; Kobecki, J.; Malinowski, M.; Pormańczuk, K.; Chabowski, M. Neurological Complications after Thoracic Endovascular Aortic Repair. Does the Left Subclavian Artery Coverage without Revascularization Increase the Risk of Neurological Complications in Patients after Thoracic Endovascular Aortic Repair? J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2019, 14, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oderich, G.S.; Pereira, A.A.; Rabinstein, A.A.; Mendes, B.C.; Pulido, J.N. Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome from Induced Hypertension during Endovascular Thoracoabdominal Aortic Aneurysm Repair. J. Vasc. Surg. 2015, 61, 1062–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shields, L.B.E.; Johnson, J.R.; Shields, C.B. Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome Following a Thoracic Discectomy–Induced Dural Leak: Case Report. J. Neurosurg. Spine 2016, 25, 586–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geocadin, R.G. Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 2171–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, S.; Koizumi, S.; Koyama, T. Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome After Thoraco-Abdominal Aortic Replacement. EJVES Vasc. Forum 2023, 58, 19–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, F.; Park, J.; Chow, K.; Chen, A.; Walsworth, M.K. Avoiding Peripheral Nerve Injury in Arterial Interventions. Diagn. Interv. Radiol. 2019, 25, 380–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoglio, L.; Oderich, G.; Melloni, A.; Gargiulo, M.; Kölbel, T.; Adam, D.J.; Di Marzo, L.; Piffaretti, G.; Agrusa, C.J.; Van den Eynde, W.; et al. Multicentre International Registry of Open Surgical Versus Percutaneous Upper Extremity Access During Endovascular Aortic Procedures. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2023, 65, 729–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piazza, M.; Squizzato, F.; Pratesi, G.; Parlani, G.; Simonte, G.; Giudice, R.; Mansour, W.; Veraldi, G.F.; Gennai, S.; Antonello, M.; et al. Editor’s Choice—Outcomes of Off the Shelf Outer Branched Versus Inner Branched Endografts in the Treatment of Thoraco-Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm in the B.R.I.O. (BRanched Inner—Outer) Study Group. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2024, 68, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkok, A. Cholesterol-Embolization Syndrome: Current Perspectives. Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 2019, 15, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.W.; Kang, I.S. Cholesterol Embolization Syndrome Presenting with Multifocal Cerebral Infarction After Thoracic Endovascular Aortic Repair: A Case Report. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Risk Factor | Effect on SCI Risk | Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Long extent of aortic coverage | Strongly increases up to >8–10% | Feezor et al. [32]; Bisdas et al. [33]. |

| Previous aortic surgery | Up to three-fold increase | Bisdas et al. [33]. |

| LSA coverage without revascularization | Increased risk of SCI and posterior stroke | Hiraoka et al. [37]; Xodo et al. [36]. |

| Bilateral hypogastric artery occlusion | Independent predictor of SCI | Xodo et al. [36]. |

| Acute complicated type B dissection | Nearly double SCI risk | Potter et al. [38]; Alzghari et al. [25]. |

| Intra or post-operative low mean arterial pressure | Reduce spinal cord perfusion pressure | Doering et al. [39]. |

| Prolonged operative time | Associated with higher SCI incidence | Doering et al. [39]; Bisdas et al. [33]. |

| Extensive single-stage repair | Associated with higher SCI incidence | Doering et al. [39]. |

| Chronic kidney disease | Independent predictor of SCI | Aucoin et al [29]. |

| Combined assessment of coverage length, prior surgery, renal insufficiency | Stratifies SCI risk from 2–3% up to 15% | Brisard et al [26]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Miceli, F.; Ascione, M.; Cangiano, R.; Marzano, A.; Di Girolamo, A.; Gagliardo, G.; di Marzo, L.; Mansour, W. Neurological Complications After Thoracic Endovascular Repair (TEVAR): A Narrative Review of the Incidence, Mechanisms and Strategies for Prevention and Management. J. Pers. Med. 2026, 16, 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16020077

Miceli F, Ascione M, Cangiano R, Marzano A, Di Girolamo A, Gagliardo G, di Marzo L, Mansour W. Neurological Complications After Thoracic Endovascular Repair (TEVAR): A Narrative Review of the Incidence, Mechanisms and Strategies for Prevention and Management. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2026; 16(2):77. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16020077

Chicago/Turabian StyleMiceli, Francesca, Marta Ascione, Rocco Cangiano, Antonio Marzano, Alessia Di Girolamo, Giovanni Gagliardo, Luca di Marzo, and Wassim Mansour. 2026. "Neurological Complications After Thoracic Endovascular Repair (TEVAR): A Narrative Review of the Incidence, Mechanisms and Strategies for Prevention and Management" Journal of Personalized Medicine 16, no. 2: 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16020077

APA StyleMiceli, F., Ascione, M., Cangiano, R., Marzano, A., Di Girolamo, A., Gagliardo, G., di Marzo, L., & Mansour, W. (2026). Neurological Complications After Thoracic Endovascular Repair (TEVAR): A Narrative Review of the Incidence, Mechanisms and Strategies for Prevention and Management. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 16(2), 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16020077