Comprehensive Landscape of Diagnostic, Prognostic and Predictive Biomarkers in Colorectal Cancer: From Genomics to Multi-Omics Integration in Precision Medicine

Abstract

1. Introduction

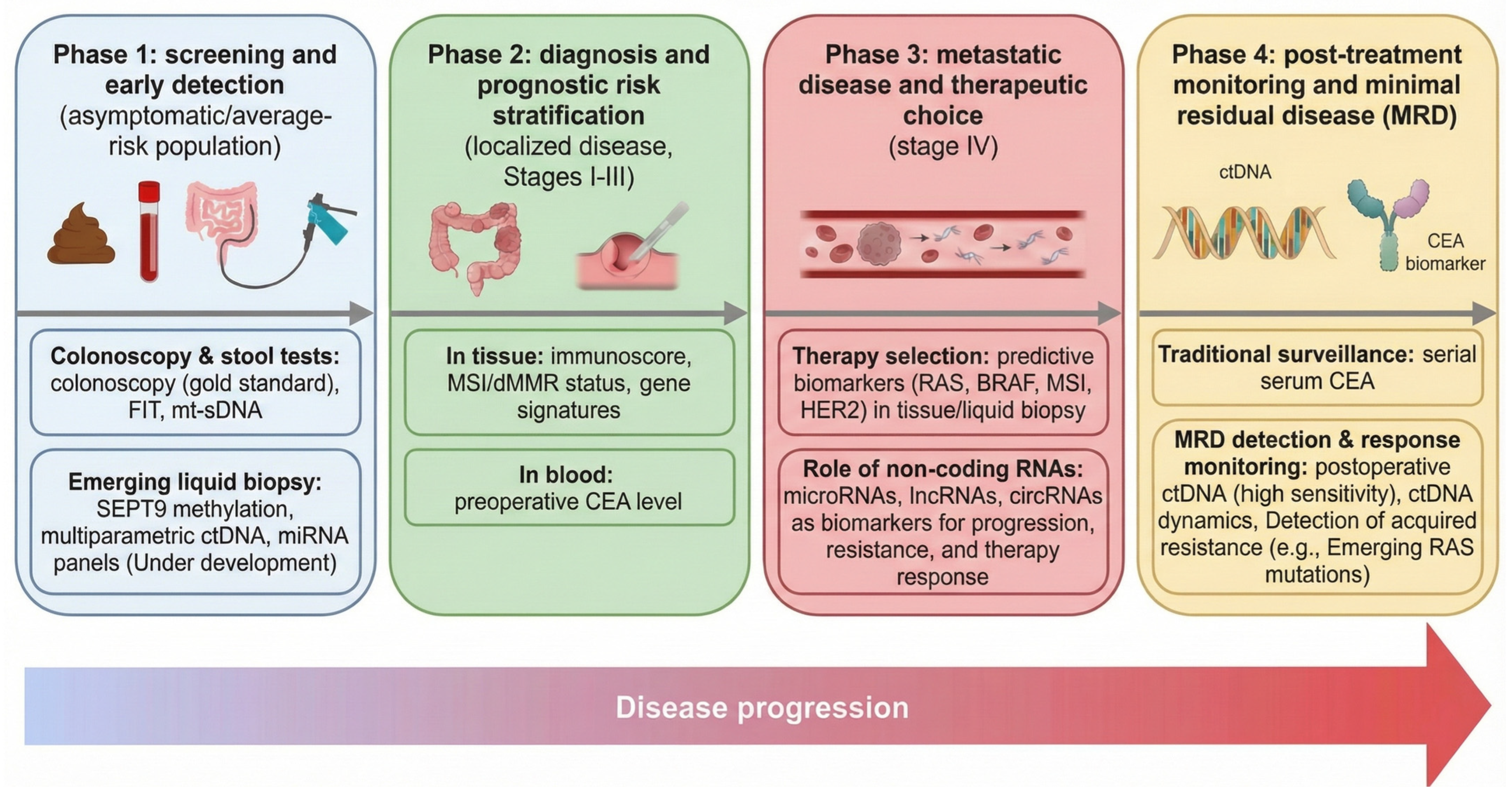

2. Diagnostic Biomarkers in Colorectal Cancer

2.1. Traditional Serum Tumor Markers

2.2. DNA-Based Biomarkers in Stool and Blood

2.3. RNA-Based Biomarkers

2.4. Other Emerging Biomarkers and Combined Approaches

3. Prognostic Biomarkers in Colorectal Cancer

3.1. Tumor-Based Prognostic Factors

3.2. Circulating Prognostic Biomarkers

3.3. Integrative and Multi-Omics Prognostic Approaches

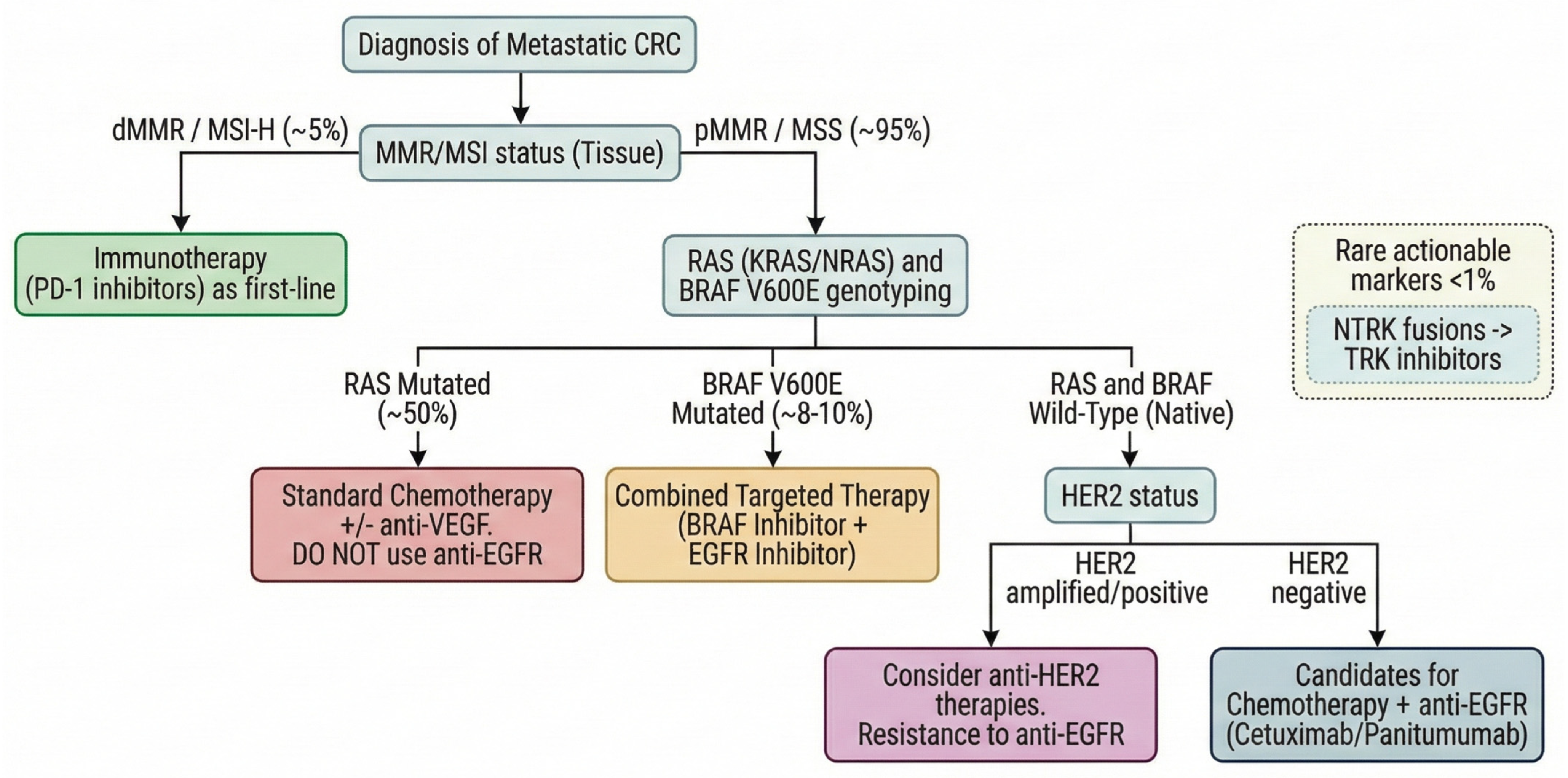

4. Predictive Biomarkers: Treatment Selection and Therapeutic Response Monitoring

4.1. Microsatellite Instability and Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor (ICI) Therapy

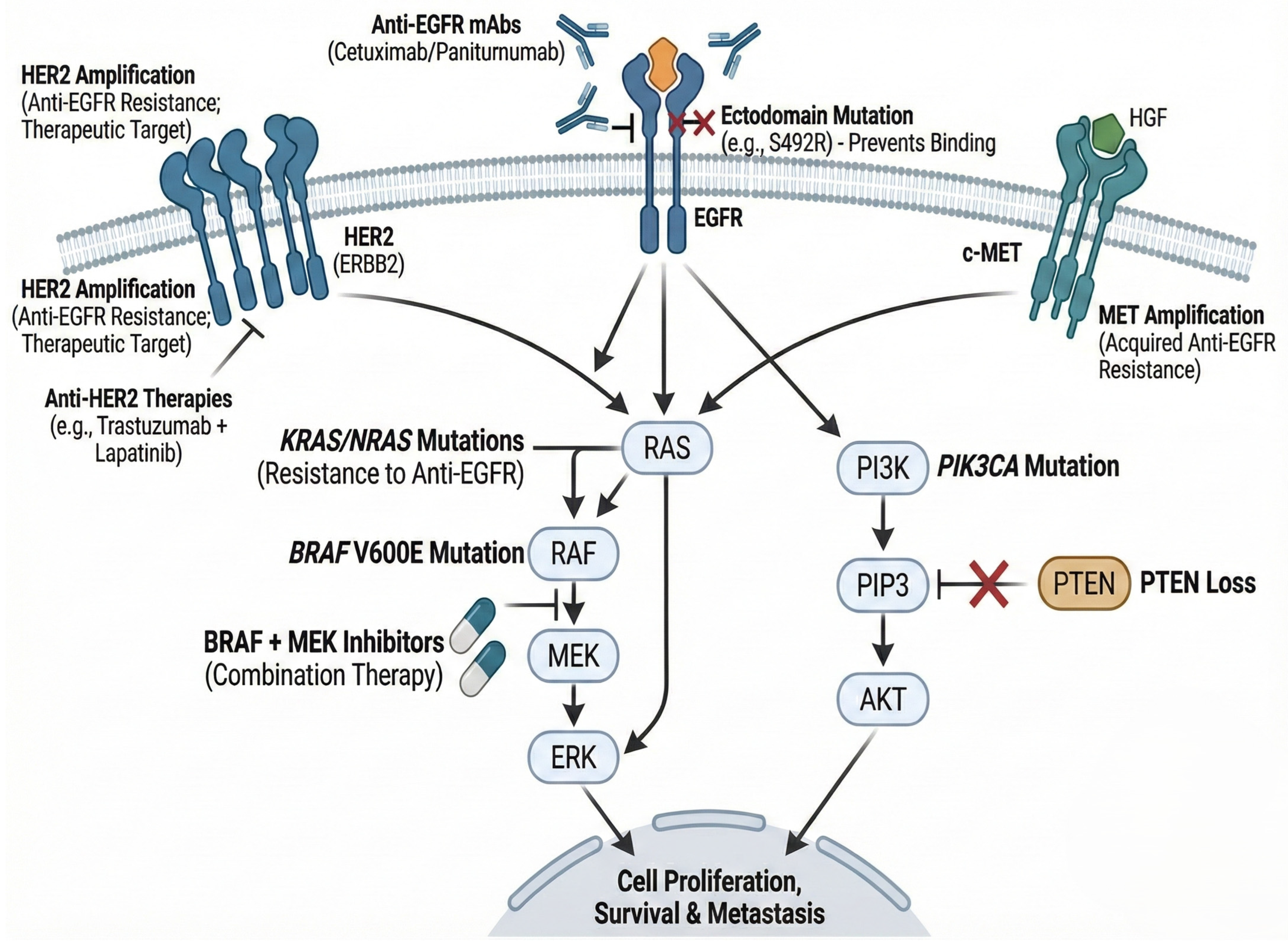

4.2. RAS/RAF/EGFR Pathway Alterations

4.3. HER2 and Other Emerging Predictive Biomarkers

4.4. Biomarkers for Therapeutic Response Monitoring

5. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADC | Antibody-drug conjugate |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| AUC | Area under the curve |

| CA19-9 | Carbohydrate antigen 19-9 |

| CEA | Carcinoembryonic antigen |

| cfDNA | Cell-free DNA |

| CMS | Consensus molecular subtype |

| CRC | Colorectal cancer |

| CTC | Circulating tumor cell |

| CSV | Cell-surface vimentin |

| ctDNA | Circulating tumor DNA |

| ctRNA | Circulating tumor RNA |

| dMMR | Deficient mismatch repair |

| EGFR | Epidermal growth factor receptor |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| EMT | Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition |

| EV | Extracellular vesicle |

| FIT | Fecal immunochemical test |

| FOBT | Fecal occult blood test |

| HER2 | Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 |

| HR | Hazard ratio |

| ICI | Immune checkpoint inhibitor |

| IHC | Immunohistochemistry |

| lncRNA | Long non-coding RNA |

| M2-PK | M2-pyruvate kinase |

| mCRC | Metastatic colorectal cancer |

| MMR | Mismatch repair |

| miRNA | MicroRNA |

| MRD | Minimal residual disease |

| MSI | Microsatellite instability |

| MSI-H | Microsatellite instability-high |

| MSS | Microsatellite stable |

| mt-sDNA | Multitarget stool DNA test |

| NCCN | National Comprehensive Cancer Network |

| NGS | Next-generation sequencing |

| NTRK | Neurotrophic tropomyosin receptor kinase |

| OS | Overall survival |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| PFS | Progression-free survival |

| PDO | Patient-derived organoid |

| PD-1 | Programmed death-1 |

| PD-L1 | Programmed death-ligand 1 |

| qPCR | Quantitative polymerase chain reaction |

| TGF-β | Transforming growth factor beta |

| TILs | Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes |

| TMB | Tumor mutational burden |

| TNM | Tumor-node-metastasis staging system |

| TRK | Tropomyosin receptor kinase |

| tsRNA | tRNA-derived small RNA |

| tRF | tRNA-derived fragment |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

References

- Zhou, J.; Yang, Q.; Zhao, S.; Sun, L.; Li, R.; Wang, J.; Wang, L.; Wang, D. Evolving Landscape of Colorectal Cancer: Global and Regional Burden, Risk Factor Dynamics, and Future Scenarios (the Global Burden of Disease 1990–2050). Ageing Res. Rev. 2025, 104, 102666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, E.; Arnold, M.; Gini, A.; Lorenzoni, V.; Cabasag, C.J.; Laversanne, M.; Vignat, J.; Ferlay, J.; Murphy, N.; Bray, F. Global Burden of Colorectal Cancer in 2020 and 2040: Incidence and Mortality Estimates from GLOBOCAN. Gut 2023, 72, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, H.; Heisser, T.; Cardoso, R.; Hoffmeister, M. Reduction in Colorectal Cancer Incidence by Screening Endoscopy. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 21, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, T.; Fujimoto, A.; Igarashi, Y. Colorectal Cancer: Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and Public Health Strategies. Digestion 2025, 106, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Zhu, H.; Liu, W.; Miao, J.; Mao, Y.; Li, Q. Prognostic and Predictive Molecular Biomarkers in Colorectal Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1532924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashouri, K.; Wong, A.; Mittal, P.; Torres-Gonzalez, L.; Lo, J.H.; Soni, S.; Algaze, S.; Khoukaz, T.; Zhang, W.; Yang, Y.; et al. Exploring Predictive and Prognostic Biomarkers in Colorectal Cancer: A Comprehensive Review. Cancers 2024, 16, 2796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Xu, X.; Chen, R.; Zhang, M.; Mei, Z.; Zhang, S. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors for Patients with Microsatellite Instability-High Colorectal Cancer: Protocol of a Pooled Analysis of Clinical Trials. Front. Oncol. 2024, 13, 1331937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponomaryova, A.A.; Rykova, E.Y.; Solovyova, A.I.; Tarasova, A.S.; Kostromitsky, D.N.; Dobrodeev, A.Y.; Afanasiev, S.A.; Cherdyntseva, N.V. Genomic and Transcriptomic Research in the Discovery and Application of Colorectal Cancer Circulating Markers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein-Scory, S.; Baraniskin, A.; Schmiegel, W.; Mika, T.; Schroers, R.; Held, S.; Heinrich, K.; Tougeron, D.; Modest, D.P.; Schwaner, I.; et al. Evaluation of Circulating Tumor DNA as a Prognostic and Predictive Biomarker in BRAF V600E Mutated Colorectal Cancer—Results from the FIRE-4.5 Study. Mol. Oncol. 2025, 19, 344–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Q.; Yuan, Z.; Hu, H.; Zhang, W.; Wang, G.; Wang, X. Genome-Wide Discovery of Circulating Cell-Free DNA Methylation Biomarkers for Colorectal Cancer Detection. Clin. Epigenet. 2023, 15, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, D.; Gao, X.; Wang, L.; Yin, H.; Feng, L.; Zhu, Y. Circulating Tumor DNA for MRD Detection in Colorectal Cancer: Recent Advances and Clinical Implications. Biomark. Res. 2025, 13, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiakanikas, P.; Adamopoulos, P.G.; Tsirba, D.; Artemaki, P.I.; Papadopoulos, I.N.; Kontos, C.K.; Scorilas, A. High Expression of a tRNAPro Derivative Associates with Poor Survival and Independently Predicts Colorectal Cancer Recurrence. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Pan, Y.; Li, Z.; Hu, K. tRNA-Derived Small RNAs: Their Role in the Mechanisms, Biomarkers, and Therapeutic Strategies of Colorectal Cancer. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Xu, X. Long Non-Coding RNA Signature in Colorectal Cancer: Research Progression and Clinical Application. Cancer Cell Int. 2023, 23, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pająk, W.; Kleinrok, J.; Pec, J.; Michno, K.; Wojtas, J.; Badach, M.; Teresińska, B.; Baj, J. Micro RNA in Colorectal Cancer—Potential Diagnostic and Prognostic Markers—An Updated Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 8615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesolato, S.E.; González-Gamo, D.; Barabash, A.; Claver, P.; de la Serna, S.C.; Domínguez-Serrano, I.; Dziakova, J.; de Juan, C.; Torres, A.J.; Iniesta, P. Expression Analysis of Hsa-miR-181a-5p, Hsa-miR-143-3p, Hsa-miR-132-3p and Hsa-miR-23a-3p as Biomarkers in Colorectal Cancer—Relationship to the Body Mass Index. Cancers 2023, 15, 3324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higareda-Almaraz, J.C.; Mancuso, F.M.; Canal-Noguer, P.; Kruusmaa, K.; Bertossi, A. Multiomics Signature Reveals Network Regulatory Mechanisms in a CRC Continuum. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argilés, G.; Tabernero, J.; Labianca, R.; Hochhauser, D.; Salazar, R.; Iveson, T.; Laurent-Puig, P.; Quirke, P.; Yoshino, T.; Taieb, J.; et al. Localised Colon Cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow-Up. Ann. Oncol. 2020, 31, 1291–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L.; Wagle, N.S.; Cercek, A.; Smith, R.A.; Jemal, A. Colorectal Cancer Statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2023, 73, 233–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dantas, A.A.G.; De Oliveira, N.P.D.; Costa, G.A.B.; Martins, L.F.L.; Dos Santos, J.E.M.; Migowski, A.; De Camargo Cancela, M.; De Souza, D.L.B. Multilevel Analysis of Social Determinants of Advanced Stage Colorectal Cancer Diagnosis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 9667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, X.-Y.; Li, Q.-Q.; Zeng, Y. Clinical Application of Liquid Biopsy in Colorectal Cancer: Detection, Prediction, and Treatment Monitoring. Mol. Cancer 2024, 23, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannucci, A.; Goel, A. Stool and Blood Biomarkers for Colorectal Cancer Management: An Update on Screening and Disease Monitoring. Mol. Cancer 2024, 23, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shweikeh, F.; Zeng, Y.; Jabir, A.R.; Whittenberger, E.; Kadatane, S.P.; Huang, Y.; Mouchli, M.; Castillo, D.R. The Emerging Role of Blood-Based Biomarkers in Early Detection of Colorectal Cancer: A Systematic Review. Cancer Treat. Res. Commun. 2024, 42, 100872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niedzielska, J.; Jastrzębski, T. Carcinoembryonic Antigen (CEA): Origin, Role in Oncology, and Concentrations in Serum and Peritoneal Fluid. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawicki, T.; Ruszkowska, M.; Danielewicz, A.; Niedźwiedzka, E.; Arłukowicz, T.; Przybyłowicz, K.E. A Review of Colorectal Cancer in Terms of Epidemiology, Risk Factors, Development, Symptoms and Diagnosis. Cancers 2021, 13, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, H.; Wei, L.; Wang, Q.; Tang, S.; Gan, J. Grading Carcinoembryonic Antigen Levels Can Enhance the Effectiveness of Prognostic Stratification in Patients with Colorectal Cancer: A Single-Centre Retrospective Study. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e084219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lișcu, H.-D.; Verga, N.; Atasiei, D.-I.; Badiu, D.-C.; Dumitru, A.V.; Ultimescu, F.; Pavel, C.; Stefan, R.-E.; Manole, D.-C.; Ionescu, A.-I. Biomarkers in Colorectal Cancer: Actual and Future Perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.; Teng, T.Z.J.; Shelat, V.G. Carbohydrate Antigen 19-9—Tumor Marker: Past, Present, and Future. World J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2020, 12, 468–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gramkow, M.H.; Mosgaard, C.S.; Schou, J.V.; Nordvig, E.H.; Dolin, T.G.; Lykke, J.; Nielsen, D.L.; Pfeiffer, P.; Qvortrup, C.; Yilmaz, M.K.; et al. The Prognostic Role of Circulating CA19–9 and CEA in Patients with Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Treat. Res. Commun. 2025, 43, 100907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.W.; Pourmorady, J.S.; Laine, L. Use of Fecal Occult Blood Testing as a Diagnostic Tool for Clinical Indications: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 115, 662–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.C.; Leite-Silva, P.; Tavares, F.; Bento, M.J.; Libânio, D.; Dinis-Ribeiro, M. An Organized Fecal Immunochemical Test-Based Screening Program Impacts Colorectal Cancer Early Diagnosis and Survival in the Short Term. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, B.T.; Xu, Y.; Daly, J.M.; Hoffman, R.M.; Dawson, J.D.; Shokar, N.K.; Zuckerman, M.J.; Molokwu, J.; Reuland, D.S.; Crockett, S.D. Comparative Performance of Common Fecal Immunochemical Tests: A Cross-Sectional Study. Ann. Intern. Med. 2024, 177, 1350–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imperiale, T.F.; Ransohoff, D.F.; Itzkowitz, S.H.; Levin, T.R.; Lavin, P.; Lidgard, G.P.; Ahlquist, D.A.; Berger, B.M. Multitarget Stool DNA Testing for Colorectal-Cancer Screening. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 370, 1287–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaukat, A.; Levin, T.R. Current and Future Colorectal Cancer Screening Strategies. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 19, 521–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffman, R.M.; Levy, B.T.; Allison, J.E. Rising Use of Multitarget Stool DNA Testing for Colorectal Cancer. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2122328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, K.W. mSEPT9 Blood Test (Epi proColon) for Colorectal Cancer Screening. Am. Fam. Physician 2019, 100, 10–11. [Google Scholar]

- Song, L.; Peng, X.; Li, Y.; Xiao, W.; Jia, J.; Dong, C.; Gong, Y.; Zhou, G.; Han, X. The SEPT9 Gene Methylation Assay Is Capable of Detecting Colorectal Adenoma in Opportunistic Screening. Epigenomics 2017, 9, 599–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, D.; Zhang, Q.; Li, L.; Luo, X.; Liang, B.; Lu, Y.; Hu, B.; Jiang, H. Methylated Septin9 Has Moderate Diagnostic Value in Colorectal Cancer Detection in Chinese Population: A Multicenter Study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022, 22, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariharan, R.; Jenkins, M. Utility of the Methylated SEPT9 Test for the Early Detection of Colorectal Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Diagnostic Test Accuracy. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2020, 7, e000355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, D.C.; Gray, D.M.; Singh, H.; Issaka, R.B.; Raymond, V.M.; Eagle, C.; Hu, S.; Chudova, D.I.; Talasaz, A.; Greenson, J.K.; et al. A Cell-Free DNA Blood-Based Test for Colorectal Cancer Screening. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 390, 973–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessa, X.; Vidal, J.; Balboa, J.C.; Márquez, C.; Duenwald, S.; He, Y.; Raymond, V.; Faull, I.; Burón, A.; Álvarez-Urturi, C.; et al. High Accuracy of a Blood ctDNA-Based Multimodal Test to Detect Colorectal Cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2023, 34, 1187–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Cao, D.; Li, M.; Zhao, F.; Wang, P.; Mei, S.; Song, Q.; Wang, P.; Nie, Y.; Zhao, W.; et al. Integration of Multiomics Features for Blood-Based Early Detection of Colorectal Cancer. Mol. Cancer 2024, 23, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Guo, H.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wang, C.; Bu, J.; Sun, T.; Wei, J. Liquid Biopsy in Cancer: Current Status, Challenges and Future Prospects. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenne, S.S.; Madsen, P.H.; Pedersen, I.S.; Hveem, K.; Skorpen, F.; Krarup, H.B.; Giskeødegård, G.F.; Laugsand, E.A. Colorectal Cancer Detected by Liquid Biopsy 2 Years Prior to Clinical Diagnosis in the HUNT Study. Br. J. Cancer 2023, 129, 861–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Zhao, Q.; Wei, W.; Zheng, L.; Yi, S.; Li, G.; Wang, W.; Sheng, H.; Pu, H.; Mo, H.; et al. Circulating Tumor DNA Methylation Profiles Enable Early Diagnosis, Prognosis Prediction, and Screening for Colorectal Cancer. Sci. Transl. Med. 2020, 12, eaax7533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakhsh, T.; Alhazmi, S.; Farsi, A.; Yusuf, A.S.; Alharthi, A.; Qahl, S.H.; Alghamdi, M.A.; Alzahrani, F.A.; Elgaddar, O.H.; Ibrahim, M.A.; et al. Molecular Detection of Exosomal miRNAs of Blood Serum for Prognosis of Colorectal Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 8902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, D.A.R.; Eiras, M.; Gonzalez-Santos, M.; Santos, M.; Pereira, C.; Santos, L.L.; Dinis-Ribeiro, M.; Lima, L. A Preliminary Assessment of a Stool-Based microRNA Profile for Early Colorectal Cancer Screening. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 28597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sado, A.I.; Batool, W.; Ahmed, A.; Zafar, S.; Patel, S.K.; Mohan, A.; Zia, U.; Aminpoor, H.; Kumar, V.; Tejwaney, U. Role of microRNA in Colorectal Carcinoma (CRC): A Narrative Review. Ann. Med. Surg. 2023, 86, 308–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Pan, L.; Wu, D.; Yao, L.; Jiang, W.; Min, J.; Xu, S.; Deng, Z. Comparison of the Diagnostic Value of Various microRNAs in Blood for Colorectal Cancer: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. BMC Cancer 2024, 24, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, D.A.R.; Gaiteiro, C.; Santos, M.; Santos, L.; Dinis-Ribeiro, M.; Lima, L. MicroRNA Biomarkers as Promising Tools for Early Colorectal Cancer Screening—A Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, D.; Kuwada, S. miRNA as a Biomarker for the Early Detection of Colorectal Cancer. Genes 2024, 15, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, B.; Kim, Y.I.; Lee, M.; Lim, S.; Shin, Y. Enhanced Early Detection of Colorectal Cancer via Blood Biomarker Combinations Identified Through Extracellular Vesicle Isolation and Artificial Intelligence Analysis. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2025, 14, e70088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Shen, H.; Zhang, N. Advances in Extracellular Vesicle (EV) Biomarkers for Precision Diagnosis and Therapeutic in Colorectal Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1581015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delshad, M.; Sanaei, M.-J.; Mohammadi, M.H.; Sadeghi, A.; Bashash, D. Exosomal Biomarkers: A Comprehensive Overview of Diagnostic and Prognostic Applications in Malignant and Non-Malignant Disorders. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duran-Sanchon, S.; Moreno, L.; Augé, J.M.; Serra-Burriel, M.; Cuatrecasas, M.; Moreira, L.; Martín, A.; Serradesanferm, A.; Pozo, À.; Costa, R.; et al. Identification and Validation of MicroRNA Profiles in Fecal Samples for Detection of Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology 2020, 158, 947–957.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Liu, X.; Wu, Z.; Tan, H.; Yu, F.; Wang, D.; Lin, X.; Chen, Z. Unveiling the Diagnostic Power of lncRNAs in Colorectal Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. Biomed. Eng. OnLine 2025, 24, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statello, L.; Guo, C.-J.; Chen, L.-L.; Huarte, M. Author Correction: Gene Regulation by Long Non-Coding RNAs and Its Biological Functions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2021, 22, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xi, W.; Sun, X.; Wang, M.; Wang, X.; Li, K.; Jiang, R.; Jia, X.; Wang, W. Identification of Progression Related LncRNAs in Colorectal Cancer Aggressiveness. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 17258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thean, L.F.; Blöcker, C.; Li, H.H.; Lo, M.; Wong, M.; Tang, C.L.; Tan, E.K.W.; Rozen, S.G.; Cheah, P.Y. Enhancer-Derived Long Non-Coding RNAs CCAT1 and CCAT2 at Rs6983267 Has Limited Predictability for Early Stage Colorectal Carcinoma Metastasis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; E, J.; Yu, E. LncRNA CASC21 Induces HGH1 to Mediate Colorectal Cancer Cell Proliferation, Migration, EMT and Stemness. RNA Biol. 2021, 18, 369–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Lu, J.; Wang, Y.; Sheng, H.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Wu, Q.; Zheng, J.; Chen, Y.; Yang, D.; et al. The lncRNA XIST/miR-125b-2-3p Axis Modulates Cell Proliferation and Chemotherapeutic Sensitivity via Targeting Wee1 in Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Med. 2021, 10, 2423–2441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Hu, W.; Feng, J.; Geng, Y. Promotion or Remission: A Role of Noncoding RNAs in Colorectal Cancer Resistance to Anti-EGFR Therapy. Cell Commun. Signal. CCS 2022, 20, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Li, D.; Sun, L.; Qin, H.; Fan, A.; Meng, L.; Graves-Deal, R.; Glass, S.E.; Franklin, J.L.; Liu, Q.; et al. Interaction of lncRNA MIR100HG with hnRNPA2B1 Facilitates m6A-Dependent Stabilization of TCF7L2 mRNA and Colorectal Cancer Progression. Mol. Cancer 2022, 21, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, J.; Fang, X.; Sun, Z.; Gai, L.; Dai, W.; Li, H.; Yan, X.; Du, J.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, L.; et al. Non-Coding RNAs Regulate the Resistance to Anti-EGFR Therapy in Colorectal Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2022, 11, 801319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakhpazyan, N.K.; Mikhaleva, L.M.; Bedzhanyan, A.L.; Sadykhov, N.K.; Midiber, K.Y.; Konyukova, A.K.; Kontorschikov, A.S.; Maslenkina, K.S.; Orekhov, A.N. Long Non-Coding RNAs in Colorectal Cancer: Navigating the Intersections of Immunity, Intercellular Communication, and Therapeutic Potential. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaprakash, S.; Madhaiyan, P.; Gopi, Y.; Bharathy, P.; Thanikachalam, P.V. Exosomes as Biomarkers and Therapeutic Targets in Colorectal Cancer Management. Next Res. 2025, 2, 100434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barhoum, M.; Brassart-Pasco, S.; Dupont-Deshorgue, A.; Thierry, A.; Kanagaratnam, L.; Brassart, B.; Ramaholimihaso, F.; Botsen, D.; Carlier, C.; Brugel, M.; et al. Circulating Exosomal Proteins as New Diagnostic Biomarkers for Colorectal Cancer (EXOSCOL01): A Pilot Case–Controlled Study Focusing on MMP14 Potential. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2025, 39, e70016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zepeda-Rivera, M.; Minot, S.S.; Bouzek, H.; Wu, H.; Blanco-Míguez, A.; Manghi, P.; Jones, D.S.; LaCourse, K.D.; Wu, Y.; McMahon, E.F.; et al. A Distinct Fusobacterium Nucleatum Clade Dominates the Colorectal Cancer Niche. Nature 2024, 628, 424–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Sánchez, A.; Nieto-Vitoria, M.Á.; López-López, J.A.; Martínez-Crespo, J.J.; Navarro-Mateu, F. Is the Oral Pathogen, Porphyromona Gingivalis, Associated to Colorectal Cancer?: A Systematic Review. BMC Cancer 2025, 25, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che Alhadi, S.; Wan Zain, W.Z.; Zahari, Z.; Md Hashim, M.N.; Syed Abd Aziz, S.H.; Zakaria, Z.; Wong, M.P.-K.; Zakaria, A.D. The Use of M2-Pyruvate Kinase as a Stool Biomarker for Detection of Colorectal Cancer in Tertiary Teaching Hospital: A Comparative Study. Ann. Coloproctol. 2020, 36, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Yang, X.; Jiang, G.; Zhang, H.; Ge, L.; Chen, F.; Li, J.; Liu, H.; Wang, H. 5′-tRF-GlyGCC: A tRNA-Derived Small RNA as a Novel Biomarker for Colorectal Cancer Diagnosis. Genome Med. 2021, 13, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Yang, X.; Zhu, D.; Liu, X.; Nie, J.; Xu, T.; Pan, Y.; Sun, H.; Wang, S. A Novel tRNA-Derived Small RNA 5′-tiRNA-His Is a Promising Biomarker for Diagnosis of Colorectal Cancer. Carcinogenesis 2025, 46, bgaf026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westwood, A.C.; Wilson, B.I.; Laye, J.; Grabsch, H.I.; Mueller, W.; Magee, D.R.; Quirke, P.; West, N.P. Deep-Learning Enabled Combined Measurement of Tumour Cell Density and Tumour Infiltrating Lymphocyte Density as a Prognostic Biomarker in Colorectal Cancer. BJC Rep. 2025, 3, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotan, H.T.; Emilescu, R.A.; Iaciu, C.I.; Orlov-Slavu, C.M.; Olaru, M.C.; Popa, A.M.; Jinga, M.; Nitipir, C.; Schreiner, O.D.; Ciobanu, R.C. Prognostic and Predictive Determinants of Colorectal Cancer: A Comprehensive Review. Cancers 2024, 16, 3928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanzi, A.; Pagès, F.; Lagorce-Pagès, C.; Galon, J. The Consensus Immunoscore: Toward a New Classification of Colorectal Cancer. Oncoimmunology 2020, 9, 1789032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruni, D.; Angell, H.K.; Galon, J. The Immune Contexture and Immunoscore in Cancer Prognosis and Therapeutic Efficacy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2020, 20, 662–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galon, J.; Lanzi, A. Immunoscore and Its Introduction in Clinical Practice. Q. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2020, 64, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagès, F.; Mlecnik, B.; Marliot, F.; Bindea, G.; Ou, F.-S.; Bifulco, C.; Lugli, A.; Zlobec, I.; Rau, T.T.; Berger, M.D.; et al. International Validation of the Consensus Immunoscore for the Classification of Colon Cancer: A Prognostic and Accuracy Study. Lancet 2018, 391, 2128–2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; He, T.; Gao, Q.; Chang, H.; Dai, X.; Yang, J.; Liu, S.; Zhang, S.; Shan, C.; Zhang, C. The Dysfunctional Wnt Pathway Down-Regulates MLH1/SET Expression and Promotes Microsatellite Instability and Immunotherapy Response in Colorectal Cancer. Genes Dis. 2023, 11, 542–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janeeh, A.S.; Bajbouj, K.; Rah, B.; Abu-Gharbieh, E.; Hamad, M. Interplay between Tumor Cells and Immune Cells of the Colorectal Cancer Tumor Microenvironment: Wnt/β-Catenin Pathway. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1587950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ros, J.; Balconi, F.; Baraibar, I.; Saoudi Gonzalez, N.; Salva, F.; Tabernero, J.; Elez, E. Advances in Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Combination Strategies for Microsatellite Stable Colorectal Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1112276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, G.; Zhang, G.; Hu, Y.; Xu, X.; Wang, Y. Correlation between Mismatch Repair Statuses and the Prognosis of Stage I–IV Colorectal Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2024, 13, 1278398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallaro, P.M.; Stafford, C.; Cauley, C.E.; Berger, D.L.; Bordeianou, L.; Kunitake, H.; Francone, T.; Ricciardi, R. Is Microsatellite Status Associated with Prognosis in Stage II Colon Cancer with High-Risk Features? Dis. Colon Rectum 2021, 64, 545–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baxter, N.N.; Kennedy, E.B.; Bergsland, E.; Berlin, J.; George, T.J.; Gill, S.; Gold, P.J.; Hantel, A.; Jones, L.; Lieu, C.; et al. Adjuvant Therapy for Stage II Colon Cancer: ASCO Guideline Update. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 892–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, R.; Taieb, J.; Fiskum, J.; Yothers, G.; Goldberg, R.; Yoshino, T.; Alberts, S.; Allegra, C.; de Gramont, A.; Seitz, J.-F.; et al. Microsatellite Instability in Patients with Stage III Colon Cancer Receiving Fluoropyrimidine with or Without Oxaliplatin: An ACCENT Pooled Analysis of 12 Adjuvant Trials. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 642–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasello, G.; Ghidini, M.; Galassi, B.; Grossi, F.; Luciani, A.; Petrelli, F. Survival Benefit with Adjuvant Chemotherapy in Stage III Microsatellite-High/Deficient Mismatch Repair Colon Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.-C.; Jin, Y.; Lei, X.-F.; Wang, Z.-X.; Zhang, D.-S.; Wang, F.-H.; Li, Y.-H.; Xu, R.-H.; Wang, F. Impact of Mismatch Repair or Microsatellite Status on the Prognosis and Efficacy to Chemotherapy in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Patients: A Bi-Institutional, Propensity Score-Matched Study. J. Cancer 2022, 13, 2912–2921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonardi, S.; Elez, E.; Jensen, L.H.; Cutsem, E.V.; Touchefeu, Y.; Garcia-Carbonero, R.; Tougeron, D.; Mendez, G.; Schenker, M.; Fouchardiere, C.D.L.; et al. Nivolumab (NIVO) plus Ipilimumab (IPI) vs. Chemotherapy (Chemo) or NIVO Monotherapy for Microsatellite Instability-High/Mismatch Repair-Deficient (MSI-H/dMMR) Metastatic Colorectal Cancer (mCRC): Expanded Analyses from CheckMate 8HW. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, 3501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wankhede, D.; Yuan, T.; Kloor, M.; Halama, N.; Brenner, H.; Hoffmeister, M. Clinical Significance of Combined Tumour-Infiltrating Lymphocytes and Microsatellite Instability Status in Colorectal Cancer: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 9, 609–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, W.-L.; Qiu, M.-Z.; He, C.-Y.; Yang, L.-Q.; Jin, Y.; Wang, Z.-Q.; Li, Y.-H.; Xu, R.-H.; Wang, F.-H. Clinicopathologic Features and Prognosis of BRAF Mutated Colorectal Cancer Patients. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 563407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinelli, E.; Arnold, D.; Cervantes, A.; Stintzing, S.; Cutsem, E.V.; Tabernero, J.; Taieb, J.; Wasan, H.; Ciardiello, F. European Expert Panel Consensus on the Clinical Management of BRAFV600E-Mutant Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2023, 115, 102541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellio, H.; Fumet, J.D.; Ghiringhelli, F. Targeting BRAF and RAS in Colorectal Cancer. Cancers 2021, 13, 2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koulouridi, A.; Karagianni, M.; Messaritakis, I.; Sfakianaki, M.; Voutsina, A.; Trypaki, M.; Bachlitzanaki, M.; Koustas, E.; Karamouzis, M.V.; Ntavatzikos, A.; et al. Prognostic Value of KRAS Mutations in Colorectal Cancer Patients. Cancers 2022, 14, 3320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Källberg, J.; Harrison, A.; March, V.; Bērziņa, S.; Nemazanyy, I.; Kepp, O.; Kroemer, G.; Mouillet-Richard, S.; Laurent-Puig, P.; Taly, V.; et al. Intratumor Heterogeneity and Cell Secretome Promote Chemotherapy Resistance and Progression of Colorectal Cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2023, 14, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, B.; Shulman, K.; Hubert, A.; Man, S.; Geva, R.; Ben-Aharon, I.; Fennig, S.; Mishaeli, M.; Yarom, N.; Bar-Sela, G.; et al. Treatments and Clinical Outcomes in Stage II Colon Cancer Patients with 12-Gene Oncotype DX Colon Recurrence Score® Assay-Guided Therapy: Real-World Data. ESMO Open 2024, 9, 103648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Daza, J.; Itzel, T.; Betge, J.; Zhan, T.; Marmé, F.; Teufel, A. Prognostic Cancer Gene Expression Signatures: Current Status and Challenges. Cells 2021, 10, 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balta, B.; Taylor, L.; Bogale, N.; Hailu, D.; Zerhouni, Y.A. Survival and Predictors of Mortality among Colorectal Cancer Patients on Follow-up in Hawassa University Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Sidama Region, Southern Ethiopia, 2022. A 5-Year Retrospective Cohort Study. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0304820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhu, H.; Pang, X.; Mao, Y.; Yi, X.; Li, C.; Lei, M.; Cheng, X.; Liang, L.; Wu, J.; et al. Preoperative Serum CA19-9 Should Be Routinely Measured in the Colorectal Patients with Preoperative Normal Serum CEA: A Multicenter Retrospective Cohort Study. BMC Cancer 2022, 22, 962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björkman, K.; Mustonen, H.; Kaprio, T.; Kekki, H.; Pettersson, K.; Haglund, C.; Böckelman, C. CA125: A Superior Prognostic Biomarker for Colorectal Cancer Compared to CEA, CA19-9 or CA242. Tumor Biol. 2021, 43, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colon Cancer—NCCN 2025 Guidelines. Available online: https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/guidelines-detail?id=1428 (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Ren, X.; Song, M.; Liu, X.; He, W. Circulating Tumor Cells: Mechanisms and Clinical Significance in Colorectal Cancer Metastasis. Mol. Cancer 2025, 24, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdalla, T.S.A.; Meiners, J.; Riethdorf, S.; König, A.; Melling, N.; Gorges, T.; Karstens, K.-F.; Izbicki, J.R.; Pantel, K.; Reeh, M. Prognostic Value of Preoperative Circulating Tumor Cells Counts in Patients with UICC Stage I–IV Colorectal Cancer. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0252897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Yang, M.; Peng, T.; Liu, Y.; Cao, Y. Evaluation of Cell Surface Vimentin Positive Circulating Tumor Cells as a Prognostic Biomarker for Stage III/IV Colorectal Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 18791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, Y.; Watanabe, J.; Akazawa, N.; Hirata, K.; Kataoka, K.; Yokota, M.; Kato, K.; Kotaka, M.; Kagawa, Y.; Yeh, K.-H.; et al. ctDNA-Based Molecular Residual Disease and Survival in Resectable Colorectal Cancer. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 3272–3283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faulkner, L.G.; Howells, L.M.; Pepper, C.; Shaw, J.A.; Thomas, A.L. The Utility of ctDNA in Detecting Minimal Residual Disease Following Curative Surgery in Colorectal Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Br. J. Cancer 2023, 128, 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotani, D.; Oki, E.; Nakamura, Y.; Yukami, H.; Mishima, S.; Bando, H.; Shirasu, H.; Yamazaki, K.; Watanabe, J.; Kotaka, M.; et al. Molecular Residual Disease and Efficacy of Adjuvant Chemotherapy in Patients with Colorectal Cancer. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yee, E.J.; McCarter, M.D.; Vogel, J.D.; Schulick, R.D.; Lieu, C.; Lentz, R.W. From Early Detection To Advanced Therapies: How Circulating Tumor DNA Is Transforming the Care of Colorectal Cancer. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2025, 27, 1464–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negro, S.; Pulvirenti, A.; Trento, C.; Indraccolo, S.; Ferrari, S.; Scarpa, M.; Urso, E.D.L.; Bergamo, F.; Pucciarelli, S.; Deidda, S.; et al. Circulating Tumor DNA as a Real-Time Biomarker for Minimal Residual Disease and Recurrence Prediction in Stage II Colorectal Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliyeva, T.; Siddiqui, H.; Natche, J.; Al-Wraikat, Y.A.; Hossain, F.M.; El-Amri, I. Prognostic Value of Circulating Tumor DNA for Recurrence Risk in Stage III Colorectal Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Color. Cancer, 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, H.T.; Nagayama, S.; Otaki, M.; Chin, Y.M.; Fukunaga, Y.; Ueno, M.; Nakamura, Y.; Low, S.-K. Tumor-Informed or Tumor-Agnostic Circulating Tumor DNA as a Biomarker for Risk of Recurrence in Resected Colorectal Cancer Patients. Front. Oncol. 2023, 12, 1055968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Li, W.; Dong, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, D.; Wang, J.; Zhou, L.; He, G. Precision Medicine in Colorectal Cancer: Leveraging Multi-Omics, Spatial Omics, and Artificial Intelligence. Clin. Chim. Acta 2024, 559, 119686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadian Rad, N.; Sosef, O.; Seegers, J.; Koolen, L.J.E.R.; Hoofwijk, J.J.W.A.; Woodruff, H.C.; Hoofwijk, T.A.G.M.; Sosef, M.; Lambin, P. Prognostic Models for Colorectal Cancer Recurrence Using Carcinoembryonic Antigen Measurements. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1368120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.; Gao, Q.; Wang, Z.; Xu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhang, L.; Xu, Y.; Zhou, Q.; et al. Exploration of Multi-Omics Liquid Biopsy Approaches for Multi-Cancer Early Detection: The PROMISE Study. Innovation 2025, 7, 101076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, S.; Heng, S.; Xie, S.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, J.; Yu, C.; Lin, Y.; Qi, X. Integrated Multi-Omics and Machine Learning Reveal an Immunogenic Cell Death-Related Signature for Prognostic Stratification and Therapeutic Optimization in Colorectal Cancer. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1606874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Dai, X.; Zhou, C.-C.; Li, K.; Zhang, Y.; Lou, X.-Y.; Zhu, Y.-M.; Sun, Y.-L.; Peng, B.-X.; Cui, W. Integrated Analysis of the Faecal Metagenome and Serum Metabolome Reveals the Role of Gut Microbiome-Associated Metabolites in the Detection of Colorectal Cancer and Adenoma. Gut 2022, 71, 1315–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badic, B.; Tixier, F.; Cheze Le Rest, C.; Hatt, M.; Visvikis, D. Radiogenomics in Colorectal Cancer. Cancers 2021, 13, 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, D.T.; Diaz, L.A.; Kim, T.W.; Van Cutsem, E.; Geva, R.; Jäger, D.; Hara, H.; Burge, M.; O’Neil, B.H.; Kavan, P.; et al. Pembrolizumab for Previously Treated, Microsatellite Instability-High/Mismatch Repair-Deficient Advanced Colorectal Cancer: Final Analysis of KEYNOTE-164. Eur. J. Cancer Oxf. Engl. 2023, 186, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- André, T.; Shiu, K.-K.; Kim, T.W.; Jensen, B.V.; Jensen, L.H.; Punt, C.J.A.; Smith, D.; Garcia-Carbonero, R.; Alcaide-Garcia, J.; Gibbs, P.; et al. Pembrolizumab versus Chemotherapy in Microsatellite Instability-High or Mismatch Repair-Deficient Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: 5-Year Follow-up from the Randomized Phase III KEYNOTE-177 Study. Ann. Oncol. 2025, 36, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Nivolumab Plus Ipilimumab for Untreated Unresectable or Metastatic Colorectal Cancer with High Microsatellite Instability or Mismatch Repair Deficiency; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: Technology Appraisals; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE): London, UK, 2025; ISBN 978-1-4731-7028-5. [Google Scholar]

- Figaroa, O.J.A.; Spaanderman, I.T.; Goedegebuure, R.S.A.; Cirkel, G.M.; Jeurissen, F.J.F.; Creemers, G.J.; Bins, A.D.; Tuynman, J.; Buffart, T.E. Treatment with Checkpoint Inhibitors for Unresectable Non-Metastatic Mismatch Repair Deficient Intestinal Cancer; A Case Series. BJC Rep. 2025, 3, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gandini, A.; Puglisi, S.; Pirrone, C.; Martelli, V.; Catalano, F.; Nardin, S.; Seeber, A.; Puccini, A.; Sciallero, S. The Role of Immunotherapy in Microsatellites Stable Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: State of the Art and Future Perspectives. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1161048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwamoto, M.; Ueda, K.; Kawamura, J. Neoadjuvant Treatment for Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer: Current Status and Future Directions. Cancers 2025, 17, 2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cercek, A.; Foote, M.B.; Rousseau, B.; Smith, J.J.; Shia, J.; Sinopoli, J.; Weiss, J.; Lumish, M.; Temple, L.; Patel, M.; et al. Nonoperative Management of Mismatch Repair–Deficient Tumors. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 392, 2297–2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heregger, R.; Huemer, F.; Steiner, M.; Gonzalez-Martinez, A.; Greil, R.; Weiss, L. Unraveling Resistance to Immunotherapy in MSI-High Colorectal Cancer. Cancers 2023, 15, 5090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ma, Y.; Wu, Z.; Zeng, F.; Song, B.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Lui, S.; Wu, M. Tumor Mutational Burden Predicting the Efficacy of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Colorectal Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 751407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobin, H.; Garvin, S.; Hagman, H.; Nodin, B.; Jirström, K.; Brunnström, H. The Prognostic Value of Programmed Death-Ligand 1 (PD-L1) Expression in Resected Colorectal Cancer without Neoadjuvant Therapy—Differences between Antibody Clones and Cell Types. BMC Cancer 2024, 24, 1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azcue, P.; Encío, I.; Guerrero Setas, D.; Suarez Alecha, J.; Galbete, A.; Mercado, M.; Vera, R.; Gomez-Dorronsoro, M.L. PD-L1 as a Prognostic Factor in Early-Stage Colon Carcinoma within the Immunohistochemical Molecular Subtype Classification. Cancers 2021, 13, 1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Guan, H.; Feng, X.; Liu, M.; Shao, J.; Liu, M.; He, J.; Jin, Y.; Zhu, J.; Zheng, C. Emerging Strategies in Colorectal Cancer Immunotherapy: Enhancing Efficacy and Survival. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1616414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steup, C.; Kennel, K.B.; Neurath, M.F.; Fichtner-Feigl, S.; Greten, F.R. Current and Emerging Concepts for Systemic Treatment of Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Gut 2025, 74, 2070–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biller, L.H.; Schrag, D. Diagnosis and Treatment of Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: A Review. JAMA 2021, 325, 669–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, L.F.; Noronha, M.M.; de Menezes, J.S.A.; da Conceição, L.D.; Almeida, L.F.C.; Cappellaro, A.P.; Belotto, M.; Biachi de Castria, T.; Peixoto, R.D.; Megid, T.B.C. Anti-EGFR Therapy in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: Identifying, Tracking, and Overcoming Resistance. Cancers 2025, 17, 2804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cervantes, A.; Adam, R.; Roselló, S.; Arnold, D.; Normanno, N.; Taïeb, J.; Seligmann, J.; Baere, T.D.; Osterlund, P.; Yoshino, T.; et al. Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow-Up. Ann. Oncol. 2023, 34, 10–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.; Wang, Z.; Lv, W.; Pan, H. The Role of Anti-EGFR Monoclonal Antibody in mCRC Maintenance Therapy. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9, 870395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, R.; Pudlarz, T.; Delattre, J.-F.; Colle, R.; André, T. Molecular Targets for the Treatment of Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Cancers 2020, 12, 2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouchahda, M.; Saffroy, R.; Karaboué, A.; Hamelin, J.; Innominato, P.; Saliba, F.; Lévi, F.; Bosselut, N.; Lemoine, A. Undetectable RAS-Mutant Clones in Plasma: Possible Implication for Anti-EGFR Therapy and Prognosis in Patients with RAS-Mutant Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. JCO Precis. Oncol. 2020, 4, 1070–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, H.-L.; Lin, C.-C.; Sung, Y.-C.; Chen, S.-H.; Chen, L.-T.; Jiang, J.-K.; Wang, J.-Y. The Emergence of RAS Mutations in Patients with RAS Wild-Type mCRC Receiving Cetuximab as First-Line Treatment: A Noninterventional, Uncontrolled Multicenter Study. Br. J. Cancer 2023, 129, 947–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holz, A.; Paul, B.; Zapf, A.; Pantel, K.; Joosse, S.A. Circulating Tumor DNA as Prognostic Marker in Patients with Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Undergoing Systemic Therapy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2025, 139, 102999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolazzo, C.; Magri, V.; Marino, L.; Belardinilli, F.; Di Nicolantonio, F.; De Renzi, G.; Caponnetto, S.; De Meo, M.; Giannini, G.; Santini, D.; et al. Genomic Landscape and Survival Analysis of ctDNA “Neo-RAS Wild-Type” Patients with Originally RAS Mutant Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1160673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaeger, R.; Weiss, J.; Pelster, M.S.; Spira, A.I.; Barve, M.; Ou, S.-H.I.; Leal, T.A.; Bekaii-Saab, T.S.; Paweletz, C.P.; Heavey, G.A.; et al. Adagrasib with or without Cetuximab in Colorectal Cancer with Mutated KRAS G12C. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Kang, R.; Tang, D. The KRAS-G12C Inhibitor: Activity and Resistance. Cancer Gene Ther. 2022, 29, 875–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakayama, I.; Hirota, T.; Shinozaki, E. BRAF Mutation in Colorectal Cancers: From Prognostic Marker to Targetable Mutation. Cancers 2020, 12, 3236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabernero, J.; Grothey, A.; Van Cutsem, E.; Yaeger, R.; Wasan, H.; Yoshino, T.; Desai, J.; Ciardiello, F.; Loupakis, F.; Hong, Y.S.; et al. Encorafenib Plus Cetuximab as a New Standard of Care for Previously Treated BRAF V600E–Mutant Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: Updated Survival Results and Subgroup Analyses from the BEACON Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trullas, A.; Delgado, J.; Koenig, J.; Fuerstenau, U.; Dedorath, J.; Hausmann, S.; Stock, T.; Enzmann, H.; Pignatti, F. The EMA Assessment of Encorafenib in Combination with Cetuximab for the Treatment of Adult Patients with Metastatic Colorectal Carcinoma Harbouring the BRAFV600E Mutation Who Have Received Prior Therapy. ESMO Open 2021, 6, 100031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopetz, S.; Yoshino, T.; Van Cutsem, E.; Eng, C.; Kim, T.W.; Wasan, H.S.; Desai, J.; Ciardiello, F.; Yaeger, R.; Maughan, T.S.; et al. Encorafenib, Cetuximab and Chemotherapy in BRAF-Mutant Colorectal Cancer: A Randomized Phase 3 Trial. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 901–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Shen, X.; Chen, G.; Du, J. Drug Resistance in Colorectal Cancer: From Mechanism to Clinic. Cancers 2022, 14, 2928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.-X.; Fu, P.-Y.; Zhang, C.; Li, L.; Huang, W.-T. Mesenchymal-Epithelial Transition Factor Amplification Correlates with Adverse Pathological Features and Poor Clinical Outcome in Colorectal Cancer. World J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2024, 16, 1395–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albadari, N.; Xie, Y.; Li, W. Deciphering Treatment Resistance in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: Roles of Drug Transports, EGFR Mutations, and HGF/c-MET Signaling. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 14, 1340401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grassilli, E.; Cerrito, M.G. Emerging Actionable Targets to Treat Therapy-Resistant Colorectal Cancers. Cancer Drug Resist. 2022, 5, 36–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ríos-Hoyo, A.; Monzonís, X.; Vidal, J.; Linares, J.; Montagut, C. Unveiling Acquired Resistance to Anti-EGFR Therapies in Colorectal Cancer: A Long and Winding Road. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1398419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, T.; Ang, A.; Boedigheimer, M.; Kim, T.W.; Li, J.; Cascinu, S.; Ruff, P.; Satya Suresh, A.; Thomas, A.; Tjulandin, S.; et al. Frequency of S492R Mutations in the Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor: Analysis of Plasma DNA from Patients with Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Treated with Panitumumab or Cetuximab Monotherapy. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2020, 21, 891–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Geng, S.; Luo, H.; Wang, W.; Mo, Y.-Q.; Luo, Q.; Wang, L.; Song, G.-B.; Sheng, J.-P.; Xu, B. Signaling Pathways Involved in Colorectal Cancer: Pathogenesis and Targeted Therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tardito, S.; Matis, S.; Zocchi, M.R.; Benelli, R.; Poggi, A. Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Targeting in Colorectal Carcinoma: Antibodies and Patient-Derived Organoids as a Smart Model to Study Therapy Resistance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaghi, C.; Tosi, F.; Mauri, G.; Bonazzina, E.; Amatu, A.; Bencardino, K.; Piscazzi, D.; Roazzi, L.; Villa, F.; Maggi, M.; et al. Targeting HER2 in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: Current Therapies, Biomarker Refinement, and Emerging Strategies. Drugs 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siena, S.; Raghav, K.; Masuishi, T.; Yamaguchi, K.; Nishina, T.; Elez, E.; Rodriguez, J.; Chau, I.; Di Bartolomeo, M.; Kawakami, H.; et al. HER2-Related Biomarkers Predict Clinical Outcomes with Trastuzumab Deruxtecan Treatment in Patients with HER2-Expressing Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: Biomarker Analyses of DESTINY-CRC01. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 10213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekaii-Saab, T.S.; Lach, K.; Hsu, L.-I.; Siadak, M.; Stecher, M.; Ward, J.; Beckerman, R.; Strickler, J.H. Impact of Anti-EGFR Therapies on HER2-Positive Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis of Clinical Outcomes. Oncologist 2023, 28, 885–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strickler, J.H.; Yoshino, T.; Graham, R.P.; Siena, S.; Bekaii-Saab, T. Diagnosis and Treatment of ERBB2-Positive Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: A Review. JAMA Oncol. 2022, 8, 760–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartore-Bianchi, A.; Lonardi, S.; Martino, C.; Fenocchio, E.; Tosi, F.; Ghezzi, S.; Leone, F.; Bergamo, F.; Zagonel, V.; Ciardiello, F.; et al. Pertuzumab and Trastuzumab Emtansine in Patients with HER2-Amplified Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: The Phase II HERACLES-B Trial. ESMO Open 2020, 5, e000911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strickler, J.H.; Cercek, A.; Siena, S.; André, T.; Ng, K.; Cutsem, E.V.; Wu, C.; Paulson, A.S.; Hubbard, J.M.; Coveler, A.L.; et al. Tucatinib plus Trastuzumab for Chemotherapy-Refractory, HER2-Positive, RAS Wild-Type Unresectable or Metastatic Colorectal Cancer (MOUNTAINEER): A Multicentre, Open-Label, Phase 2 Study. Lancet Oncol. 2023, 24, 496–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siena, S.; Bartolomeo, M.D.; Raghav, K.; Masuishi, T.; Loupakis, F.; Kawakami, H.; Yamaguchi, K.; Nishina, T.; Fakih, M.; Elez, E.; et al. Trastuzumab Deruxtecan (DS-8201) in Patients with HER2-Expressing Metastatic Colorectal Cancer (DESTINY-CRC01): A Multicentre, Open-Label, Phase 2 Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, 779–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westphalen, C.B.; Krebs, M.G.; Le Tourneau, C.; Sokol, E.S.; Maund, S.L.; Wilson, T.R.; Jin, D.X.; Newberg, J.Y.; Fabrizio, D.; Veronese, L.; et al. Genomic Context of NTRK1/2/3 Fusion-Positive Tumours from a Large Real-World Population. NPJ Precis. Oncol. 2021, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.-Y. TRK Inhibitors: Tissue-Agnostic Anti-Cancer Drugs. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, E.S.; Fan, W.; Knepper, T.C.; Schell, M.J.; Sahin, I.H.; Fleming, J.B.; Xie, H. Prognostic and Predictive Value of PIK3CA Mutations in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Target. Oncol. 2022, 17, 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, E.; Kelly, C.; Hay, J.; Sansom, O.; Maka, N.; Oien, K.; Iveson, T.; Saunders, M.; Kerr, R.; Tomlinson, I.; et al. Prognostic and Predictive Value of Immunoscore in Stage III Colorectal Cancer: Pooled Analysis of Cases From the SCOT and IDEA-HORG Studies. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 2207–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taniguchi, H.; Uehara, K.; Ishikawa, T.; Okochi, O.; Akazawa, N.; Okuda, H.; Hasegawa, H.; Shiozawa, M.; Kataoka, M.; Satake, H.; et al. BRAF V600E and Non-V600E Mutations in RAS Wild-Type Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: Prognostic and Therapeutic Insights from a Nationwide, Multicenter, Observational Study (J-BROS). Cancers 2025, 17, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadgar-Zankbar, L.; Elahi, Z.; Shariati, A.; Khaledi, A.; Razavi, S.; Khoshbayan, A. Exploring the Role of Fusobacterium Nucleatum in Colorectal Cancer: Implications for Tumor Proliferation and Chemoresistance. Cell Commun. Signal. CCS 2024, 22, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulhati, P.; Yin, J.; Pederson, L.; Schmoll, H.-J.; Hoff, P.; Douillard, J.-Y.; Hecht, J.R.; Tournigand, C.; Tebbut, N.; Chibaudel, B.; et al. Threshold Change in CEA as a Predictor of Non-Progression to First-Line Systemic Therapy in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Patients with Elevated CEA. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2020, 112, 1127–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titu, S.; Ilies, R.A.; Mocan, T.; Irimie, A.; Gata, V.A.; Lisencu, C.I. Evaluation of Carcinoembryonic Antigen as a Prognostic Marker for Colorectal Cancer Relapse: Insights from Postoperative Surveillance. Med. Sci. 2025, 13, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tie, J.; Wang, Y.; Lo, S.N.; Lahouel, K.; Cohen, J.D.; Wong, R.; Shapiro, J.D.; Harris, S.J.; Khattak, A.; Burge, M.E.; et al. Circulating Tumor DNA Analysis Guiding Adjuvant Therapy in Stage II Colon Cancer: 5-Year Outcomes of the Randomized DYNAMIC Trial. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 1509–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciardiello, D.; Martinelli, E.; Troiani, T.; Mauri, G.; Rossini, D.; Martini, G.; Napolitano, S.; Famiglietti, V.; Del Tufo, S.; Masi, G.; et al. Anti-EGFR Rechallenge in Patients with Refractory ctDNA RAS/BRAF Wt Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: A Nonrandomized Controlled Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e245635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folprecht, G.; Reinacher-Schick, A.; Weitz, J.; Lugnier, C.; Kraeft, A.-L.; Wisser, S.; Aust, D.E.; Weiss, L.; von Bubnoff, N.; Kramer, M.; et al. The CIRCULATE Trial: Circulating Tumor DNA Based Decision for Adjuvant Treatment in Colon Cancer Stage II Evaluation (AIO-KRK-0217). Clin. Color. Cancer 2022, 21, 170–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartore-Bianchi, A.; Pietrantonio, F.; Lonardi, S.; Mussolin, B.; Rua, F.; Crisafulli, G.; Bartolini, A.; Fenocchio, E.; Amatu, A.; Manca, P.; et al. Circulating Tumor DNA to Guide Rechallenge with Panitumumab in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: The Phase 2 CHRONOS Trial. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 1612–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iguchi, K.; Shiozawa, M.; Uchiyama, M.; Asari, M.; Numata, K.; Rino, Y.; Saito, A. Temporal Dynamics of RAS Mutations in Circulating Tumor DNA in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: Clinical Significance of Mutation Loss during Treatment. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 150, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussen, B.M.; Abdullah, S.T.; Abdullah, S.R.; Younis, Y.M.; Hidayat, H.J.; Rasul, M.F.; Mohamadtahr, S. Exosomal Non-Coding RNAs: Blueprint in Colorectal Cancer Metastasis and Therapeutic Targets. Non-Coding RNA Res. 2023, 8, 615–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, C.-M.; Pei, X.M.; Yeung, M.H.Y.; Jin, N.; Ng, S.S.M.; Tsang, H.F.; Cho, W.C.S.; Yim, A.K.-Y.; Yu, A.C.-S.; Wong, S.C.C. Exploring the Role of Circulating Cell-Free RNA in the Development of Colorectal Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrik, J.; Verbanac, D.; Fabijanec, M.; Hulina-Tomašković, A.; Čeri, A.; Somborac-Bačura, A.; Petlevski, R.; Grdić Rajković, M.; Rumora, L.; Krušlin, B.; et al. Circulating Tumor Cells in Colorectal Cancer: Detection Systems and Clinical Utility. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, F.; Sun, X.; Sun, J.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y. Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Colorectal Cancer Metastasis and Progression: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Strategies. Cell Death Discov. 2025, 11, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Biomarker | Specimen | Method | Sensitivity/ Specificity | Clinical Use or Guideline Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guaiac fecal occult blood test (gFOBT) | Stool | Chemical reaction (peroxidase) | ~70–80% (CRC) or ~60–80% (advanced adenoma)/~90% | Traditional screening (older); largely superseded by FIT due to diet confounders; still reduces CRC mortality. |

| Fecal immunochemical test (FIT) | Stool | Immunoassay (anti-hemoglobin Ab) | ~79%/94% | First-line CRC screening (guideline-recommended in adults 45–75; e.g., USPSTF Grade A). |

| Multitarget stool DNA (Cologuard) | Stool | DNA assay (methylated BMP3/NDRG4 + KRAS + hemoglobin) | ~92%/87% | FDA-approved (2014) for average-risk screening (3-year interval); endorsed as alternative to FIT by USPSTF/ACS. |

| Plasma mSEPT9 (Epi proColon) | Blood (plasma) | Methylation-specific PCR | ~60–70%/~80–90% | FDA-approved (2016) for CRC screening (ages ≥ 45) but has inferior sensitivity; usually reserved for patients refusing other screening. |

| Plasma ctDNA (Guardant Shield) | Blood | NGS-based multi-gene cfDNA assay | ~83%/90% | Newly FDA-approved (2024) multi-cancer CRC screen; not yet in routine guidelines; performance promising but evaluation ongoing. |

| Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) | Serum | Immunoassay | ~50–70% (advanced CRC)/low in early stage | Not used for screening; guideline-recommended only for post-treatment surveillance (e.g., NCCN) (periodic monitoring for recurrence). |

| Carbohydrate Ag19-9 (CA19-9) | Serum | Immunoassay | <50% (CRC) | Not used for CRC screening or diagnosis; has limited role in advanced disease. |

| Blood miRNA panel (e.g., miR-21, miR-92a) | Blood | qRT-PCR/NGS | ~80–90% (CRC, research studies) | Experimental—various panels reported high accuracy (e.g., stool miR panel with 88% CRC sensitivity); none validated or in guidelines. |

| Stool miRNA panel (e.g., miR-21-5p, miR-199a-5p) | Stool | qRT-PCR | ~88% (CRC)/96% (CRC + advanced adenoma) | Investigational—shows promise in small studies, but not approved or recommended. |

| Biomarker/Alteration | Mechanism of Resistance | Detection Technique | Clinical Relevance/Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| MET amplification | Bypasses EGFR blockade via activation of parallel PI3K/AKT/MAPK signaling. | FISH/NGS (tissue or ctDNA) | Found in up to 18% of acquired resistance cases without RAS/RAF mutations nor microsatellite instability. Potential target for MET inhibitors (e.g., capmatinib) + anti-EGFR. |

| EGFR ectodomain mutations (e.g., S492R) | Prevents binding of specific monoclonal antibodies (e.g., cetuximab) to the receptor. | Liquid biopsy (ctDNA)/NGS | Mutations may prohibit cetuximab binding but allow panitumumab efficacy. Highlights the utility of liquid biopsy. |

| HER2 amplification | Heterodimerization with EGFR or independent signaling activation. | IHC/ISH/NGS | Predictive of anti-EGFR resistance. Actionable target with dual HER2 blockade (e.g., trastuzumab + lapatinib/tucatinib). |

| NTRK fusions | Constitutive activation of TRK kinases driving tumor growth independent of EGFR. | IHC (pan-TRK)/NGS (RNA-seq) | Rare (<1%) but highly actionable with TRK inhibitors (larotrectinib, entrectinib). |

| Fusobacterium nucleatum | Modulates autophagy and immune microenvironment to support chemo/immunotherapy resistance. | qPCR (stool/tissue)/16S rRNA sequencing | High load correlates with recurrence and worse prognosis. Potential target for microbiome-modulating therapies. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Agüera-Sánchez, A.; Peña-Ros, E.; Martínez-Martínez, I.; García-Molina, F. Comprehensive Landscape of Diagnostic, Prognostic and Predictive Biomarkers in Colorectal Cancer: From Genomics to Multi-Omics Integration in Precision Medicine. J. Pers. Med. 2026, 16, 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16010048

Agüera-Sánchez A, Peña-Ros E, Martínez-Martínez I, García-Molina F. Comprehensive Landscape of Diagnostic, Prognostic and Predictive Biomarkers in Colorectal Cancer: From Genomics to Multi-Omics Integration in Precision Medicine. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2026; 16(1):48. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16010048

Chicago/Turabian StyleAgüera-Sánchez, Alfonso, Emilio Peña-Ros, Irene Martínez-Martínez, and Francisco García-Molina. 2026. "Comprehensive Landscape of Diagnostic, Prognostic and Predictive Biomarkers in Colorectal Cancer: From Genomics to Multi-Omics Integration in Precision Medicine" Journal of Personalized Medicine 16, no. 1: 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16010048

APA StyleAgüera-Sánchez, A., Peña-Ros, E., Martínez-Martínez, I., & García-Molina, F. (2026). Comprehensive Landscape of Diagnostic, Prognostic and Predictive Biomarkers in Colorectal Cancer: From Genomics to Multi-Omics Integration in Precision Medicine. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 16(1), 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16010048