Natural Protein-Restricted Diets and Their Impact on Linear Growth in Patients with Propionic and Methylmalonic Acidemia: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

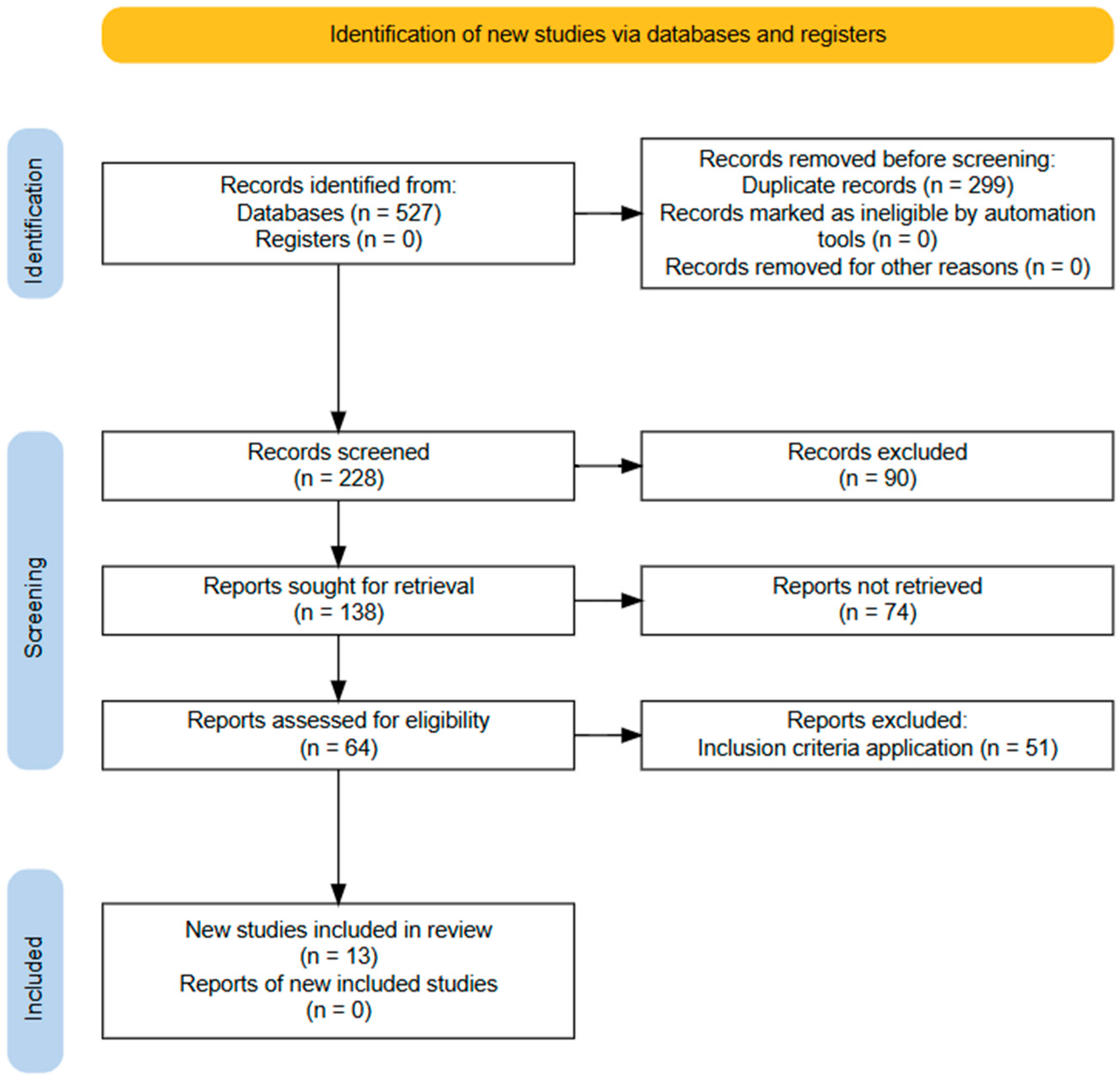

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Protein and Energy Intake Concerning Ponderal Growth

4.2. Amino Acids Imbalance

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Definition |

| Met Thr | Methionine Threonine |

| Val | Valine |

| Ile | Isoleucine |

| Leu | Leucine |

| MTVI | Methionine, Threonine, Valine, Isoleucine |

| PA | propionic acidemia |

| MMA | methylmalonic acidemia |

| PCC | Propionyl-CoA carboxylase |

| MUT0 | Non-responsive MMA |

| MUT- | Responsive MMA |

| MMA CblA, CblB, CblC | Cofactor deficiency of the mutase enzyme |

| RDA | Recommended Dietary Allowances |

| PS | Protein substitute protein |

| BBB | Blood–brain barrier |

| LAT-1 | Transporter of large, branched, and aromatic neutral amino acids |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis |

| PICOS | The acronym is used to help formulate a well-defined research question. P: population; I: Intervention/exposure; C: comparison; O: outcome; S: Study design |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| H/A | Height per age |

| P:E | Protein energy and Energy ratio |

| IGF-1 | Insulin-like growth factor-1 |

References

- Baumgartner, M.R.; Hörster, F.; Dionisi-Vici, C.; Haliloglu, G.; Karall, D.; Chapman, K.A.; Huemer, M.; Hochuli, M.; Assoun, M.; Ballhausen, D.; et al. Proposed Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Methylmalonic and Propionic Acidemia. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2014, 9, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyfi, F.; Talebi, S.; Varasteh, A.-R. Methylmalonic Acidemia Diagnosis by Laboratory Methods. Rep. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2016, 5, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Chandler, R.J.; Venditti, C.P. Gene Therapy for Methylmalonic Acidemia: Past, Present, and Future. Hum. Gene Ther. 2019, 30, 1236–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forny, P.; Hörster, F.; Ballhausen, D.; Chakrapani, A.; Chapman, K.A.; Dionisi-Vici, C.; Dixon, M.; Grünert, S.C.; Grunewald, S.; Haliloglu, G.; et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of methylmalonic acidaemia and propionic acidaemia: First revision. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2021, 44, 566–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, A.; Pinto, A.; Evans, S.; Almeida, M.F.; Assoun, M.; Belanger-Quintana, A.; Bernabei, S.M.; Bollhalder, S.; Cassiman, D.; Champion, H.; et al. Dietary practices in propionic acidemia: A European survey. Mol. Genet. Metab. Rep. 2017, 13, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, A.; Evans, S.; Daly, A.; Almeida, M.F.; Assoun, M.; Belanger-Quintana, A.; Bernabei, S.M.; Bollhalder, S.; Cassiman, D.; Champion, H.; et al. Dietary practices in methylmalonic acidaemia: A European survey. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 33, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurecki, E.; Ueda, K.; Frazier, D.; Rohr, F.; Thompson, A.; Hussa, C.; Obernolte, L.; Reineking, B.; Roberts, A.M.; Yannicelli, S.; et al. Nutrition management guideline for propionic acidemia: An evidence- and consensus-based approach. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2019, 126, 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joint FAO; WHO; UNU Expert Consultation on Protein and Amino Acid Requirements in Human Nutrition; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; World Health Organization; United Nations University. Protein and Amino Acid Requirements in Human Nutrition: Report of a Joint FAO/WHO/UNU Expert Consultation; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43411 (accessed on 17 June 2023).

- U.S. Food and Drugs Administration (FDA). Medical Foods Guidance Documents & Regulatory Information. 2022 [Accessed 7 December 2022]. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/food/guidance-documents-regulatory-information-topic-food-and-dietary-supplements/medical-foods-guidance-documents-regulatory-information (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Myles, J.G.; Manoli, I.; Venditti, C.P. Effects of medical food leucine content in the management of methylmalonic and propionic acidemias. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2018, 21, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, R.A.; Joshi, M.; Jeoung, N.H.; Obayashi, M. Overview of the Molecular and Biochemical Basis of Branched-Chain Amino Acid Catabolism. J. Nutr. 2005, 135, 1527S–1530S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, L.E.; Burns, C.; Drumm, M.; Gaughan, S.; Sailer, M.; Baker, P.R., II. Impact on Isoleucine and Valine Supplementation When Decreasing Use of Medical Food in the Nutritional Management of Methylmalonic Acidemia. Nutrients 2020, 12, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, J.W.; Badaloo, A.; Wilson, L.; Taylor-Bryan, C.; Chambers, B.; Reid, M.; Forrester, T.; Jahoor, F. Dietary Supplementation with Aromatic Amino Acids Increases Protein Synthesis in Children with Severe Acute Malnutrition1–4. J. Nutr. 2014, 144, 660–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manary, M.J.; Yarasheski, K.E.; Berger, R.; Abrams, E.T.; Hart, C.A.; Broadhead, R.L. Whole-Body Leucine Kinetics and the Acute Phase Response during Acute Infection in Marasmic Malawian Children. Pediatr. Res. 2004, 55, 940–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, F.A.; Suryawan, A.; Orellana, R.A.; Gazzaneo, M.C.; Nguyen, H.V.; Davis, T.A. Differential effects of long-term leucine infusion on tissue protein synthesis in neonatal pigs. Amino Acids 2011, 40, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cota, D.; Proulx, K.; Smith, K.A.B.; Kozma, S.C.; Thomas, G.; Woods, S.C.; Seeley, R.J. Hypothalamic mTOR Signaling Regulates Food Intake. Science 2006, 312, 927–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, F.; Guo, Q.; Duan, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhong, Y.; Yang, Y.; Yin, Y. Leucine Supplementation: A Novel Strategy for Modulating Lipid Metabolism and Energy Homeostasis. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleemani, H.; Horvath, G.; Stockler-Ipsiroglu, S.; Elango, R. Determining ideal balance among branched-chain amino acids in medical formula for Propionic Acidemia: A proof of concept study in healthy children. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2022, 135, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, H.B. Nutricion. In Fisiología Humana; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2020; p. 987. [Google Scholar]

- Nyhan, W.L.; Borden, M.; Childs, B. Idiopathic hyperglycinemia: A new disorder of amino acid metabolism. II. The concentrations of other amino acids in the plasma and their modification by the administration of leucine. Pediatrics 1961, 27, 539–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NHLBI. Study Quality Assessment Tools. 2021. Available online: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Satoh, T.; Narisawa, K.; Igarashi, Y.; Saitoh, T.; Hayasaka, K.; Ichinohazama, Y.; Onodera, H.; Tada, K.; Oohara, K. Dietary therapy in two patients with vitamin B12-unresponsive methylmalonic acidemia. Eur. J. Pediatr. 1981, 135, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queen, P.M.; Acosta, P.B.; Fernhoff, P.M. The effects of spacing protein intake on nitrogen balance and plasma amino acids in a child with propionic acidemia. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 1982, 1, 305–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, N.S.; Manoli, I.; Graf, J.C.; Sloan, J.; Venditti, C.P. Variable dietary management of methylmalonic acidemia: Metabolic and energetic correlations. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 93, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujisawa, D.; Nakamura, K.; Mitsubuchi, H.; Ohura, T.; Shigematsu, Y.; Yorifuji, T.; Kasahara, M.; Horikawa, R.; Endo, F. Clinical features and management of organic acidemias in Japan. J. Hum. Genet. 2013, 58, 769–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoli, I.; Myles, J.G.; Sloan, J.L.; Shchelochkov, O.A.; Venditti, C.P. A critical reappraisal of dietary practices in methylmalonic acidemia raises concerns about the safety of medical foods. Part 1: Isolated methylmalonic acidemias. Genet. Med. 2016, 18, 386–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manoli, I.; Myles, J.G.; Sloan, J.L.; Carrillo-Carrasco, N.; Morava, E.; Strauss, K.A.; Morton, H.; Venditti, C.P. A critical reappraisal of dietary practices in methylmalonic acidemia raises concerns about the safety of medical foods. Part 2: Cobalamin C deficiency. Genet. Med. 2016, 18, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, M.; Truby, H.; Boneh, A. The Relationship between Dietary Intake, Growth, and Body Composition in Inborn Errors of Intermediary Protein Metabolism. J. Pediatr. 2017, 188, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molema, F.; Gleich, F.; Burgard, P.; van der Ploeg, A.T.; Summar, M.L.; Chapman, K.A.; Lund, A.M.; Rizopoulos, D.; Kölker, S.; Williams, M.; et al. Decreased plasma l-arginine levels in organic acidurias (MMA and PA) and decreased plasma branched-chain amino acid levels in urea cycle disorders as a potential cause of growth retardation: Options for treatment. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2019, 126, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobarak, A.; Dawoud, H.; Nofal, H.; Zoair, A. Clinical Course and Nutritional Management of Propionic and Methylmalonic Acidemias. J. Nutr. Metab. 2020, 2020, 8489707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleemani, H.; Egri, C.; Horvath, G.; Stockler-Ipsiroglu, S.; Elango, R. Dietary management and growth outcomes in children with propionic acidemia: A natural history study. JIMD Rep. 2021, 61, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mobarak, A.; Stockler, S.; Salvarinova, R.; Van Karnebeek, C.; Horvath, G. Long term follow-up of the dietary intake in propionic acidemia. Mol. Genet. Metab. Rep. 2021, 27, 100757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molema, F.; Haijes, H.A.; Janssen, M.C.; Bosch, A.M.; van Spronsen, F.J.; Mulder, M.F.; Verhoeven-Duif, N.M.; Jans, J.J.M.; van der Ploeg, A.T.; Wagenmakers, M.A.; et al. High protein prescription in methylmalonic and propionic acidemia patients and its negative association with long-term outcome. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 3622–3630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busiah, K.; Roda, C.; Crosnier, A.-S.; Brassier, A.; Servais, A.; Wicker, C.; Dubois, S.; Assoun, M.; Belloche, C.; Ottolenghi, C.; et al. Pubertal origin of growth retardation in inborn errors of protein metabolism: A longitudinal cohort study. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2024, 141, 108123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häberle, J.; Chakrapani, A.; Ah Mew, N.; Longo, N. Hyperammonaemia in classic organic acidaemias: A review of the literature and two case histories. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2018, 13, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, K.A.; Ah Mew, N.; Mickle, N.; Starin, D.; MacLeod, E. Propionic acidemia and methylmalonic aciduria: A portrait of the first 3 years—Admissions and complications. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2025, 146, 109289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bos, C.; Tomé, D. Dietary Protein and Nitrogen Utilization. J. Nutr. 2000, 130, 1868S–1873S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yannicelli, S. Nutrition therapy of organic acidaemias with amino acid-based formulas: Emphasis on methylmalonic and propionic acidaemia. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2006, 29, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornejo, V.; Raimann, E.; Pérez, B.; Desviat, L.; Arias, C. Errores innatos del metabolismo de los aminoácidos. In Errores Innatos en el Metabolismo del Niño, 4th ed.; Universitaria: Santiago, Chile, 2017; pp. 131–136. [Google Scholar]

- FAO; WHO; UNU. Human Energy Requirements. 2004. Available online: http://www.fao.org/docrep/007/y5686e/y5686e00.HTM (accessed on 2 June 2013).

- Millward, D.J.; Jackson, A.A. Protein/energy ratios of current diets in developed and developing countries compared with a safe protein/energy ratio: Implications for recommended protein and amino acid intakes. Public Health Nutr. 2004, 7, 387–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Mejía, L.A.; Fernández-Lainez, C.; Vela-Amieva, M.; Ibarra-González, I.; Guillén-López, S. The BMI Z-Score and Protein Energy Ratio in Early- and Late-Diagnosed PKU Patients from a Single Reference Center in Mexico. Nutrients 2023, 15, 957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornejo, V.; Cruchet, S. Recomendaciones y requerimiento de micro y macronutrientes. In Nutrición en el Ciclo Vital; Santiago, Chile, 2013; pp. 17–39. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nlmcatalog/101627301 (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Harris, J.A.; Benedict, F.G. A Biometric Study of Human Basal Metabolism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1918, 4, 370–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mifflin, M.D.; St Jeor, S.T.; Hill, L.A.; Scott, B.J.; Daugherty, S.A.; Koh, Y.O. A new predictive equation for resting energy expenditure in healthy individuals. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1990, 51, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, S.; Daly, A.; Wildgoose, J.; Cochrane, B.; Chahal, S.; Ashmore, C.; Loveridge, N.; MacDonald, A. Growth, Protein and Energy Intake in Children with PKU Taking a Weaning Protein Substitute in the First Two Years of Life: A Case-Control Study. Nutrients 2019, 11, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szmelcman, S.; Guggenheim, K. Interference between leucine, isoleucine and valine during intestinal absorption. Biochem. J. 1966, 100, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robredo García, I.; Grattarola, P.; Correcher Medina, P.; Abu-Sharif Bohigas, F.; Vélez García, V.; Vitoria Miñana, I.; Martínez Costa, C. Nutritional status in patients with protein metabolism disorders. Case-control study. An. Pediatría Engl. Ed. 2024, 101, 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yorifuji, T.; Muroi, J.; Uematsu, A.; Nakahata, T.; Egawa, H.; Tanaka, K. Living-related liver transplantation for neonatal-onset propionic acidemia. J. Pediatr. 2000, 137, 572–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morioka, D.; Kasahara, M.; Horikawa, R.; Yokoyama, S.; Fukuda, A.; Nakagawa, A. Efficacy of Living Donor Liver Transplantation for Patients with Methylmalonic Acidemia. Am. J. Transplant. 2007, 7, 2782–2787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakamoto, R.; Nakamura, K.; Kido, J.; Matsumoto, S.; Mitsubuchi, H.; Inomata, Y.; Endo, F. Improvement in the prognosis and development of patients with methylmalonic acidemia after living donor liver transplant. Pediatr. Transplant. 2016, 20, 1081–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai, N.R.; Stroup, B.M.; Poliner, A.; Rossetti, L.; Rawls, B.; Shayota, B.J.; Soler-Alfonso, C.; Tunuguntala, H.P.; Goss, J.; Craigen, W.; et al. Liver transplantation in propionic and methylmalonic acidemia: A single center study with literature review. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2019, 128, 431–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author and Year | Title | Design and Quality | Study Objective | Results | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Satoh T, et al., 1981 [23] | Dietary therapy in two patients with vitamin-B12 unresponsive methylmalonic acidemia | Case report (n = 2) (N/D) | To establish dietary management of vitamin B12 among subjects with non-responsive MMA under treatment. Evaluate response to different protein intake. | Case 1 -Total Protein contribution with PS: 0.6, 0.9, and 1.2 g/kg/d, negative changes were observed when the PS was removed, and a better response was obtained to treatment with 1.0 g/kg/d Natural Protein and 1.0 g/kg/d of PS. -PS provided 70–80 kcal/kg/d. Case 2: -Only total protein from Natural Protein without PS, best response with a combination of 1.2 g/kg/d Natural Protein and 1 g/kg/d SP -PS provided 125 kcal/kg/d. | The contribution of PS improved growth, as well as biochemistry, and also presented a significant weight gain. The authors suggest the use of the Natural Protein mixture with PS. |

| Queen PM, et al. 1982 [24] | The effects of spacing protein intake on nitrogen balance and plasma amino acids in a child with propionic acidemia | Case report (n = 1) (N/D) | To evaluate the effect of protein distribution on nitrogen balance and plasma aminogram in a 34-month-old child with propionic acidemia. | H/A percentile: -H/A percentile 10–25 (90.4 cm) -Relationship between NEAA and EAA (r = 4.29 and 4.02) Reference value: (r = 4.0) Total protein intake: 1 g/kg/d | Nitrogen retention was acceptable for linear growth, regardless of protein distribution. Plasma aminogram was adequate for essential amino acids. The authors recommend distributing protein evenly throughout the day. |

| Hauser NS, et al. 2011 [25] | Variable dietary management of methylmalonic acidemia: metabolic and energetic correlations | Retrospective (n = 29) Good | To document different nutritional approaches used to treat patients with MMA, measure estimated energy requirement, and analyze the dependence of estimated energy requirement on body composition, biochemical, and nutritional variables. | H/A z-score: -Non-responsive MMA < 20 y: −0.04 ± 1.2 SD. Females: −1.49 ± −1.4 SD, Males: −0.76 ± 0.9 SD. -Responsive MMA: 0.24 ± 0.9 SD. CblA = 0.78 (males) and −0.84 SD (females) CblB = −1.48 ± 2.7 SD. Natural Protein intake: -Non-responsive MMA Mut0 2–9 y (n = 10): 0.84 ± 0.17 g/kg/d 10–18 y (n = 07): 0.82 ± 0.46 g/kg/d -Responsive MMA ClbA (n = 5): 1.0 ± 0.63 g/kg/d -Responsive MMA CblB (n = 2): 0.67 g/kg/d PS intake: -Non-responsive MMA Mut0 2–9 y: 0.72 ± 0.63 g/kg/d 10–18 y: 0.64 ± 0.60 g/kg/d -Responsive MMA ClbA: 0.31 ± 0.52 g/kg/d Energy intake: -MMA (entire group) (38.7 ± 10.7 kcal/kg/d). Low average according to WHO. -MMA (entire group) 2–9 y = 43.1 ± 5.3 kcal/kg/d 10–18 y = 41.2 ± 14 kcal/kg/d -Energy consumption was lower than predicted by the Harris-Benedict and Schofield equations *** -Responsive MMA ClbA: 37.0 ± 9.0 kcal/kg/d -Responsive MMA ClbB: 36.9 ± 19.0 kcal/kg/d Total protein intake: -Average intake: 0.38 ± 2.94 g/kg/d (33% and 98% of natural protein based on RDA). -Non-responsive MMA (n = 21): 1.3304 ± 0.72 g/kg/d -Responsive MMA CblA (n = 5): 1.32 ± 0.72 g/kg/d -Responsive MMA CblB (n = 1): 0.67 g/kg/d R2 for protein intake, age, creatinine clearance, and height = 0.66. | Lower energy intake among subjects with MMA. Cases with PS and Natural Protein exceed RDA. Females with responsive MMA had a shorter height than men (H/A z-score < −1 SD). 5 cases had Val and Ile levels below recommended levels and were supplemented. |

| Fujisawa D, et al. 2013 [26] | Clinical features and organic acidemias in Japan | Retrospective (n = 119) Good | To investigate the clinical presentation and evaluate therapies used to improve long-term outcomes in MMA and PA subjects in Japan. | -PA: (n = 19) 47% natural protein restriction in the acute phase and 50% in the chronic phase. -Non-responsive MMA (n = 25) had a restriction of 88% in Natural Protein in the acute phase and 93% in the chronic phase; 69% presented failure to thrive. -Responsive MMA (n = 15) had 38.5% restriction of Natural Protein in the acute phase and 25% in the chronic phase; 30% presented failure to thrive. -70% of the non-responsive MMA had failure to thrive, and 30% in responsive MMA and PA. -Failure to thrive was considered a mortality factor in all forms of MMA (p < 0.001) -95% of subjects evaluated received L-carnitine supplementation. | Non-responsive MMA have a lower survival rate. Growth impairment is directly affected by Natural Protein restriction. |

| Manoli, I. et al. 2016 [27] | A critical reappraisal of dietary practices in methylmalonic acidemia raises concerns about the safety of medical foods. Part 1: isolated methylmalonic acidemias | Cohort (n = 61) Good | To evaluate the effects of unbalanced BCAA intake on metabolic and growth parameters in a cohort of patients with MMA. | H/A z-score: -Non-responsive MMA: Mut0 (n = 28) = −2.07 ± 1.71. (Height < 10th percentile: 66% of men and 25% of women) Mut-, Responsive MMA CblA and CblB =< −1 SD. Total Protein and Natural Protein intake: -Non-responsive MMA Mut0: 0.99 ± 0.32 g/kg/d (102 ± 30% RDA). -MMA: 2–9 y = 2.04 ± 0.81 g/kg/d (1.06 g/kg/d) (105% RDA). 10–18 y = 1.67 ± 0.73 g/kg/d (0.94/kg/d) (99.8% RDA). -Responsive MMA ClbA: 1.58 ± 0.89 g/kg/d (1.26 ± 0.56 g/kg/d Natural Protein) -Responsive MMA ClbB: 1.04 ± 0.29 g/kg/d (0.56 ± 0.15 g/kg/d Natural Protein) PS intake: -Non-responsive MMA (all): 0.78 ± 0.68 g/kg/d 2–9 y = 0.98 ± 0.68 g/kg/d. 10–18 y = 0.72 ± 0.55 g/kg/d. -Responsive MMA CblA = 0.31 ± 0.49 g/kg/d. CblB = 0.47 ± 0.40 g/kg/d. Amino acid intake: -Leu/Val or Leu/Ile was significantly higher in patients with PS. -Leu intake: Non-responsive MMA (all) 2–9 y = 222.0 ± 24.9 mg/d 10–18 y = 173.33 ± 55.6 mg/d | The PS provides between 4 and 5 times more Leu than recommended by WHO/FAO/UNU 2007 [8], and was negatively correlated with growth. Significant negative correlation between protein from PS intake and plasma concentration of Val r = −0.569 and Ile r = −0.469. Significant negative correlation between Leu/Val intake and height in patients with non-responsive H/A z-score and Mut0: r = −0.341 (n = 23) and R2 = 0.123. After adding serum creatinine factors to the model, the correlation improved to R2 = 0.296 and IGF-1 to R2 = 0.478. |

| Manoli I, et al. 2016 [28] | A critical reappraisal of dietary practices in methylmalonic acidemia raises concerns about the safety of medical foods. Part 2: cobalamin C deficiency | Cohort (n = 28) Good | To examine the effects of an unbalanced intake of branched-chain amino acids on growth in patients with CblC-responsive MMA. | H/A z-score: -Mean = −1.04 ± 1.33 SD 14 subjects with congenital microcephaly and seizures = −2.16 ± 1.04 SD. Natural Protein Intake: 21% of subjects receive less than 85% of RDA. PS intake: 32% of subjects who received PS had H/A z-score = −1.72 ± 1.01 SD. | A greater relationship was observed between the intake of Leu with Met or with Val, when they were with PS, and a negative correlation was detected with H/A z-score (r = −0.673; p = 0.033) Positive correlation between Natural Protein intake and H/A z-score: r = 0.575 Negative correlation of Met entry through the BBB compared to Leu ***. |

| Evans M, et al. 2017 [29] | The relationship between dietary intake, growth, and body composition in inborn errors of intermediary protein metabolism | Longitudinal retrospective (n = 14) Good | To examine the relationship between protein and energy (P:E) intake and growth in patients with inborn errors of metabolism, and determine a safe P:E ratio for optimal growth. | H/A z-score: 50% of subjects with PA/MMA = H/A z-score less than −1 SD, the other 50% between −1 and +1 SD. Natural Protein intake: -Decreases with age (1.5 y = 1.2 g/kg/d) (3, 6 and 11 y = 0.95 g/kg/d) -Negative correlation between Natural Protein intake and energy (n = 6) r = −0.522, p = 0.0288. -A positive correlation was observed between Total Protein intake and weight (n = 10; r = 0.56; p = 0.08), but not so with height. -Negative correlation between Natural Protein intake and the lowest fat% (n = 11; r = −0.74 **). -A correlation was obtained between the P:E ratio between 1.5 and 2.9 gr prot/100 kcal/day with optimal growth, BMI, and % fat | Despite adequate protein and energy intake, growth outcomes in patients with inborn errors of intermediary protein metabolism are not always ideal. They also show that a P:E ratio range of >1.5–<2.9 g protein/100 kcal/day correlates with optimal growth, BMI, and fat mass % in those with inborn errors of intermediary protein metabolism. |

| Molema F, et al. 2019 [30] | Decreased plasma L-arginine levels in organic acidurias (MMA and PA) and decreased plasma branched-chain amino acid levels in urea cycle disorders as a potential cause of growth retardation: Options for treatment. | Longitudinal (n = 263) Good | To study the correlation between the level of L-arginine, BCAA, and height among patients with PA/MMA and in urea cycle disorders. | H/A z-score at birth: -PA/MMA = −0.52 SD (range −5.53 to 3.48). First appointment post-diagnosis: 33% had a H/A z-score less than −2.0 SD. -In non-responsive MMA Mut0 = −1.7 ± 1.56 SD Natural protein intake: -Greater protein restriction in symptomatic individuals (Z = −2.38 *) and in those receiving PS (Z = −2.087 *). At the first visit, the average caloric prescription was 105% of the RDA, and in relation to the Natural Protein:E ratio, it was 1.23 (range: 0.37–3.33), and Total Protein:E was 1.83 (range: 0.63–4.56). Natural Protein intake with using PS: -Average natural protein intake prescription of 110% (range: 18–278%) of RDA with the PS. Plasma amino acids: -Decrease in the plasma level of Ile and Val in the first control. -Val level was < in subjects with Natural Protein restriction *** -Val and Ile levels were lower in subjects receiving the PS ***. | PA/MMA: positive association between plasma levels of L-Arg and L-Val, Natural Protein:E ratio, and H/A z-score. In the multilevel analysis, a positive correlation was observed between H/A z-score and the ratio of Natural Protein: E ***, and a negative correlation with the amount of PS ** and the age at visit ***. Authors suggest optimizing levels of these amino acids to improve the Natural Protein:E ratio and promote adequate growth. |

| Mobarak A, et al. 2020 [31] | Clinical course and nutritional management of Propionic and Methylmalonic Acidemias | Retrospective (n = 20) Good | Provide information on clinical response and long-term complications by identifying possible factors correlated with complications. | 10 PA and 10 MMA were analyzed. Average height percentile of 10.85 ± 6.71; 65% were below the 10th percentile. Total protein intake: -Total group (n = 20) 2.09 ± 0.24 g/kg/d of which 0.73 ± 0.1 g/kg/d was natural protein and 1.37 ± 0.24 g/kg/d was PS. -PA (n = 10) 2.08 ± 0.28 g/kg/d of which 0.71 ± 0.1 g/kg/d was natural protein and 1.38 ± 0.26 g/kg/d was PS. -MMA (n = 10) 2.12 ± 0.2 g/kg/d of which 0.75 ± 0.1 g/kg/d was natural protein and 1.36 ± 0.23 g/kg/d was PS. 2 cases had an intake under the RDA and had a height in the 3rd percentile. -Albumin level correlated positively with Natural Protein (r = 0.8 ***) and negatively with the PS (r = −0.48 *). -The levels of both albumin and prealbumin were positively correlated with Natural Protein. | A greater consumption of PS was observed, and a lower intake of Natural Protein was associated with a lower height percentile. It is suggested that individuals may have a better outcome with a higher intake of Natural Protein. PS should only be used in cases where patients do not meet 100–120% of their RDA. |

| Saleemani H, et al. 2021 [32] | Dietary management and growth outcomes in children with propionic acidemia: A natural history study | Longitudinal retrospective (n = 4) Good | To describe the protein and caloric intake and the long-term impact on the growth of four patients with PA. | H/A z-score: 0–5 y: average −0.72 SD (−1.36 to −0.2 SD). 5–10 y: average −1.03 SD (−1.78 to −0.23 SD) 10–18 y: average −1.4 SD. -One case was treated with growth hormone at 9 years old. Parent height: -Father > 1.70 m and mother > 1.6 m. -Expected height and actual height achieved at age 18, 3/4 below expected; 1 patient died before age 18. Sibling height: 2 brothers of 2 subjects evaluated: H/A z-score from 0 to 1 SD. Energy intake (Total Protein:E ratio): -Total Protein:E = 2.75 g/100 kcal. -Natural Protein: E = 0.9 g/100 kcal. | Although caloric and Total Protein intake covered the RDA, the H/A z-score was lower than expected. Natural Protein intake was lower, with a Natural Protein:E ratio lower than recommended. Optimal dietary management is suggested for PA, balancing the use of Natural Protein and PS, using the Natural Protein:E ratio. |

| Mobarak A., et al. 2021 [33] | Long-term follow-up of the dietary intake in propionic acidemia | Longitudinal retrospective (n = 4) Good | To provide a detailed view of the dietary intake, plasma amino acid profiles, and long-term growth parameters of 4 subjects with PA. | H/A z-score: -H/A z-score was the most affected, with an average of −1.08 ± 0.96 SD (range −6.1 to 1.81) Total protein intake (natural + PS): -Total Protein intake = 1.81 ± 0.51 g/kg/d (182 ± 50% above RDA) -Natural Protein = 0.79 ± 0.15 g/kg/d (80 ± 13% adequacy with RDA) -PS = 1.02 ± 0.49 g/kg/d (103 ± 49% adequacy according to RDA). Amino acid intake: -Average supplementation of 180 mg/d Val (17 ± 9%) due to low plasma levels. -Average Met intake under RDA recommendations and remained low in two evaluation points (1–4 y: 204.34 ± 71.27 mg/d; and 4–7 y: 355.76 ± 94.18 mg/d; d). -Average Leu intake = 362 ± 165% above the RDA. -High Leu/Val and Leu/Ile ratio. Plasma amino acid level: -Decreased levels of Val and Ile by 91% and 42%, respectively (Val: 67.41 ± 33.05 μmol/L; Ile: 49.79 ± 25.67 μmol/L) | Despite an increased intake of Total Protein and amino acids, an imbalance was observed in the ratios of BCAA, so it is suggested to monitor them. Use PS only in patients who do not meet RDAs for Natural Protein and monitor plasma amino acid levels. |

| Molema F, et al. 2021 [34] | High protein prescription in methylmalonic and propionic acidemia patients and its negative association with long-term outcome | Retrospective Cohort (n = 76) Fair | To evaluate the association of longitudinal dietary treatment, in relation to Natural Protein, PS, and Total Protein, with episodes of metabolic decompensation, long-term mitochondrial complications, cognitive development, and height. | H/A z-score: -Cohort (n = 76): most participants showed impaired growth. -Non-responsive MMA (n = 24): negative association with age and a positive association with a higher P:E ratio. Total protein intake: -Cohort: 150 ± 52% of the RDA. The RDA was exceeded in 84% of assessments. -Non-responsive MMA: 149 ± 48% of the RDA. The RDA was exceeded in 80%. -Responsive MMA: 141% of the RDA. The RDA was exceeded in 79%. -PA, early diagnosis: 154 ± 49% of the RDA. The RDA was exceeded in 91%. -PA, late diagnosis: 142% of the RDA. The RDA was exceeded in 81%. -A higher Total Protein:E ratio was associated with a greater H/A z-score in subjects with non-responsive MMA. Natural protein intake: 78% had a diet restricted in Natural Protein throughout the follow-up. -Cohort: 37% exceeded the RDA for natural protein. -Non-responsive MMA: the RDA was exceeded in 34%. -Responsive MMA: the RDA was exceeded in 53%. -PA, early diagnosis: the RDA was exceeded in 26%. -PA, late diagnosis: the RDA was exceeded in 44%. PS intake: 84% received the PS. -Higher PS intake was negatively associated with H/A z-score in all except subjects with early diagnosed PA. -MMA group: High prescription was associated with more mitochondrial complications. | The prescription of Natural Protein was above the RDA; however, subjects still received the PS. High protein intake was negatively associated with metabolic decompensation, cognitive development, and height. It is suggested to adapt the protein prescription according to the RDA, especially in the most severe forms, and provide PS when there is a deficiency. |

| Busiah K., et al. 2024 [35] | Pubertal origin of growth retardation in inborn errors of protein metabolism: A longitudinal cohort study | Longitudinal retrospective (n = 89) Good | Inherited aminoacid metabolism disorders (IAAMDs) require a lifelong protein-restricted diet. We aimed to investigate: 1/whether IAAMDs were associated with growth, pubertal, bone mineral apparent density, or body composition impairments; And associations linking height, PS, plasma amino acids, and IGF-1 concentrations. | H/A z-score: Early infancy (0–4 y): average −0.1 SD (1.3 SD). 7.7% < −2 SD. Prepubertal (4–8 y girls and 4–9 boys): average −0.3 SD (1.7 SD). 14.9% < −2 SD. Pubertal: average −1.0 SD. 31% < −2 SD. Total protein intake (natural + PS): -Total Protein intake = Early infancy 1.1 ± 0.4 g/kg/d (100 ± 38.8% above RDA); Prepubertal 1.1 ± 0.4 g/kg/d (106.4 ± 37.6% above RDA); Pubertal 0.8 ± 0.3 g/kg/d (94.8 ± 33.5% above RDA) -Natural Protein = Early infancy 0.9 ± 0.4 g/kg/d (78.9 ± 40.6% adequacy with RDA); Prepubertal 0.9 ± 0.3 g/kg/d (85.7 ± 32.6% adequacy with RDA); Pubertal 0.7 ± 0.3 g/kg/d (78.4 ± 34.3% adequacy with RDA). -PS = Early infancy 0.7 ± 0.2 g/kg/d; Prepubertal 0.5 ± 0.2 g/kg/d; Pubertal 0.4 ± 0.2 g/kg/d. Energy intake (Total Protein:E ratio): -P:E = Early infancy 1.3 ± 0.4 g/100 kcal; Prepubertal 1.5 ± 0.5 g/100 kcal; Pubertal 1.9 ± 0.7 g/100 kcal. | In early patients, overall height (SD) correlated positively with total protein/energy ratio, but not with IGF1. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ramirez, J.; Leal-Witt, M.J.; Cabello, J.F.; Cornejo, V. Natural Protein-Restricted Diets and Their Impact on Linear Growth in Patients with Propionic and Methylmalonic Acidemia: A Systematic Review. J. Pers. Med. 2026, 16, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16010004

Ramirez J, Leal-Witt MJ, Cabello JF, Cornejo V. Natural Protein-Restricted Diets and Their Impact on Linear Growth in Patients with Propionic and Methylmalonic Acidemia: A Systematic Review. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2026; 16(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleRamirez, Jessica, María Jesús Leal-Witt, Juan Francisco Cabello, and Verónica Cornejo. 2026. "Natural Protein-Restricted Diets and Their Impact on Linear Growth in Patients with Propionic and Methylmalonic Acidemia: A Systematic Review" Journal of Personalized Medicine 16, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16010004

APA StyleRamirez, J., Leal-Witt, M. J., Cabello, J. F., & Cornejo, V. (2026). Natural Protein-Restricted Diets and Their Impact on Linear Growth in Patients with Propionic and Methylmalonic Acidemia: A Systematic Review. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 16(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16010004