Female Sexual Function After Radical Treatment for MIBC: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

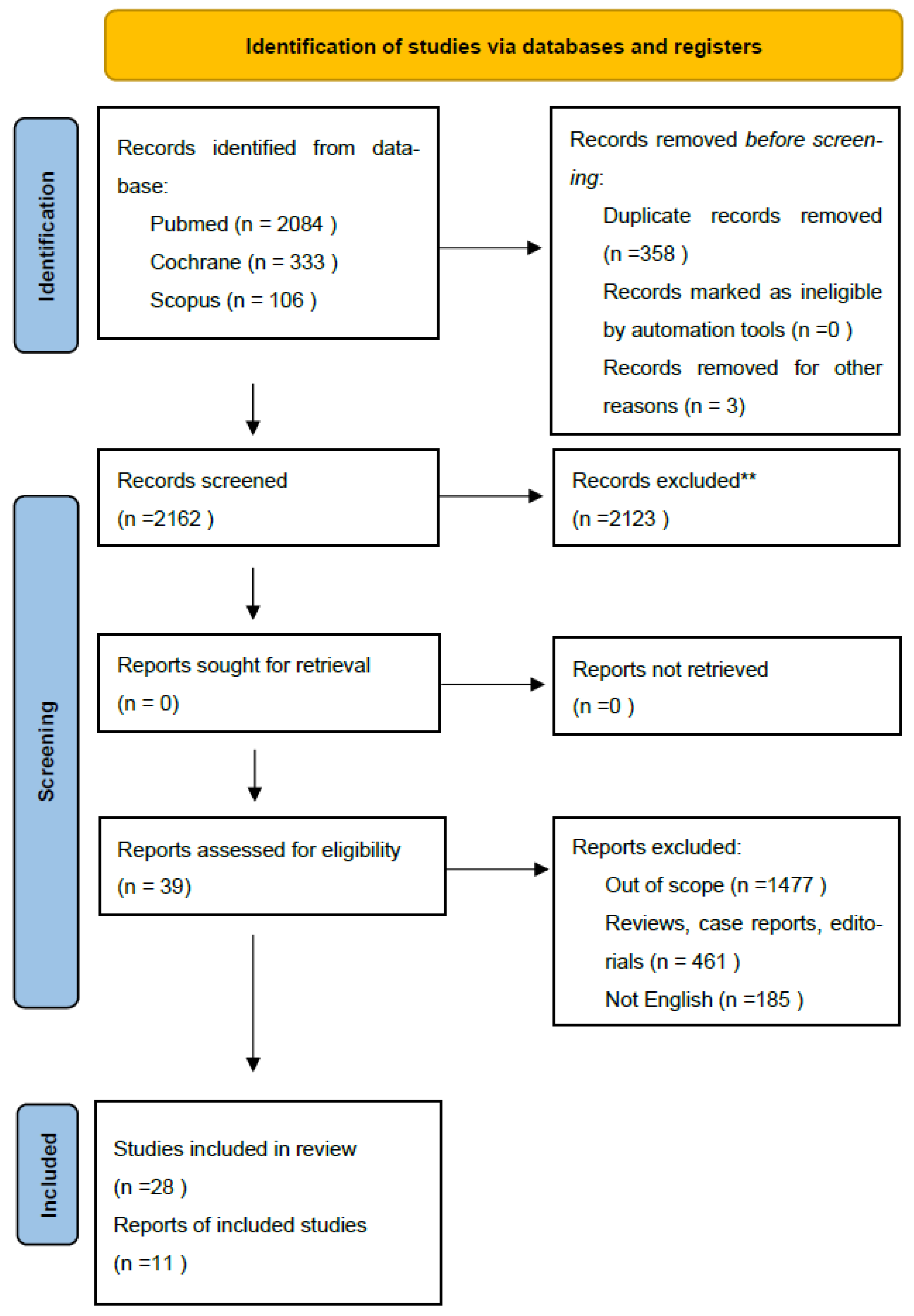

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Search Methods

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Screening Procedure

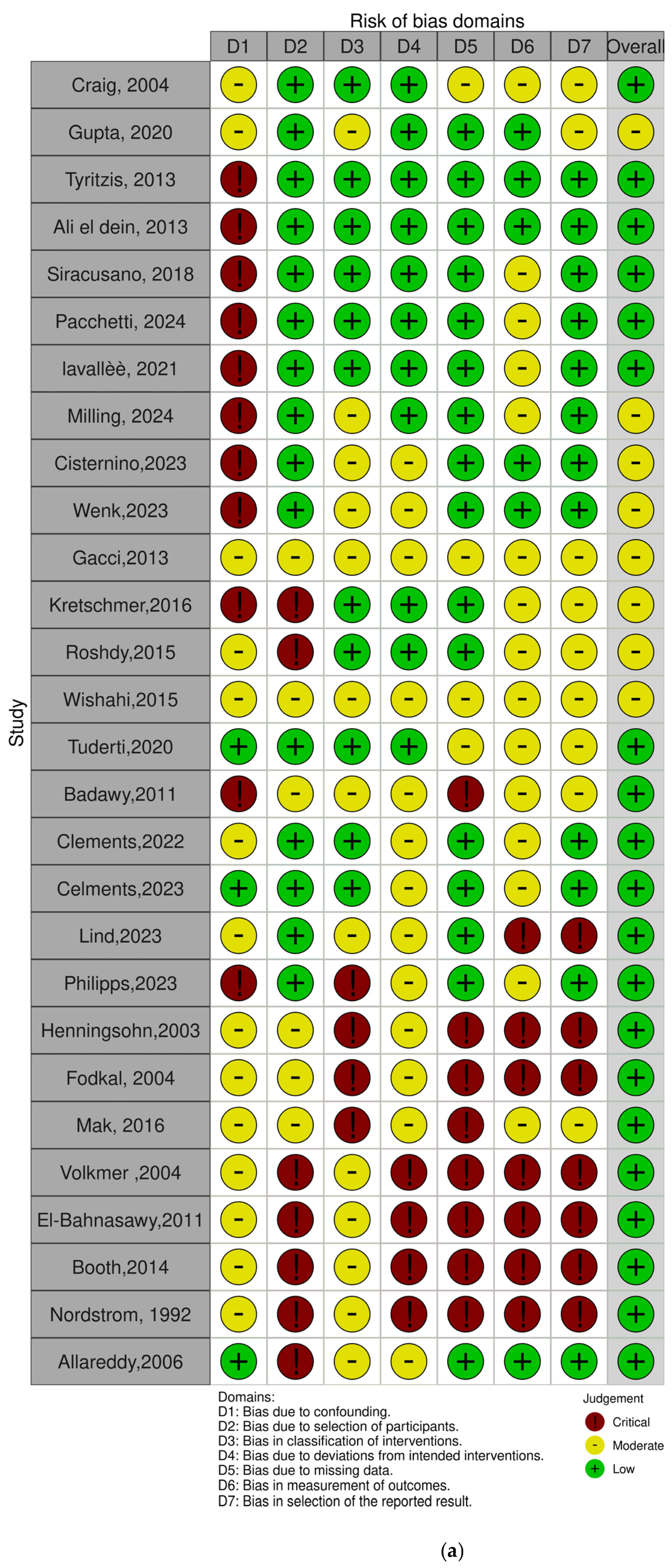

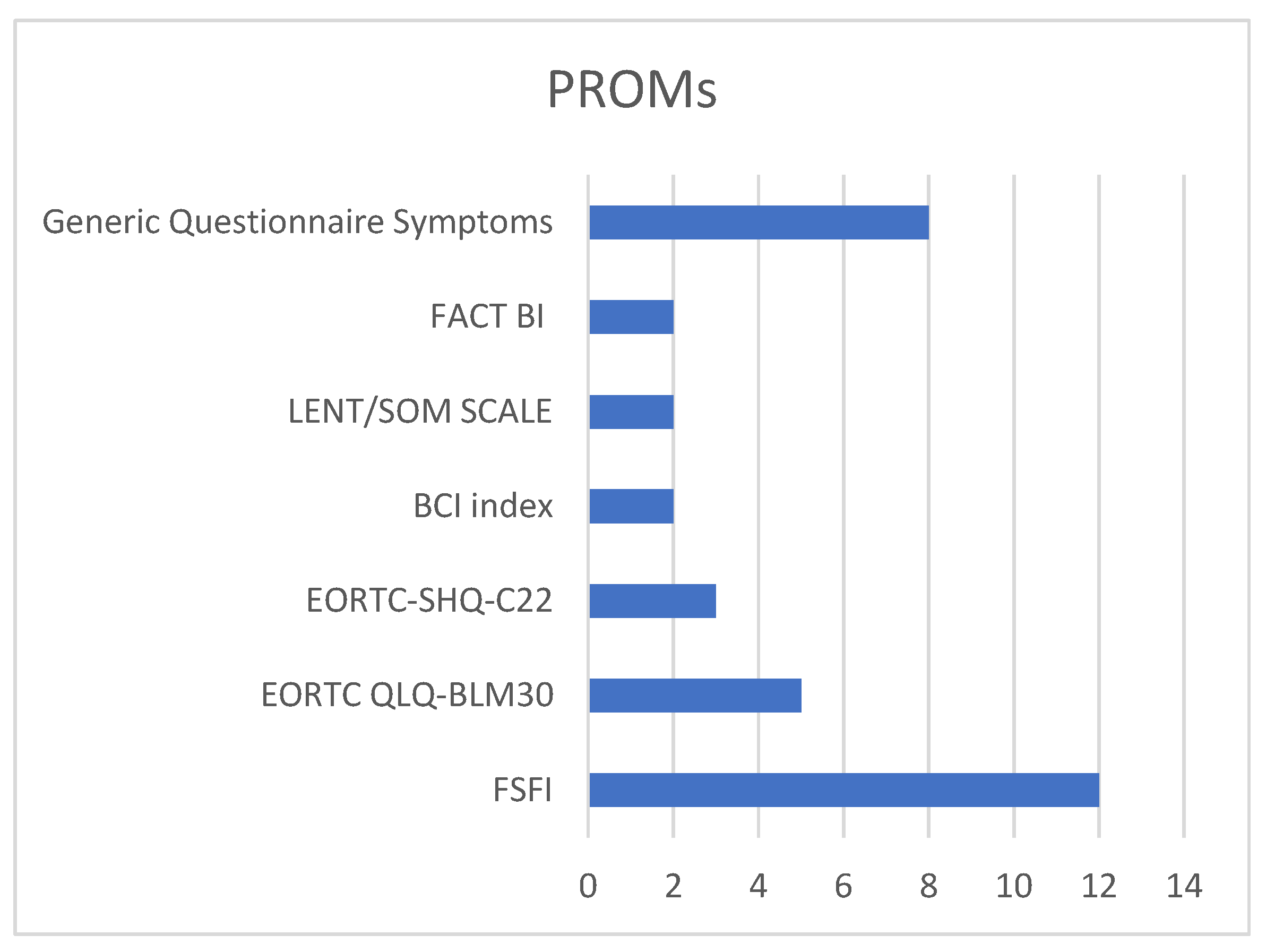

2.5. Risk of Bias

3. Results

3.1. Features of Included Studies

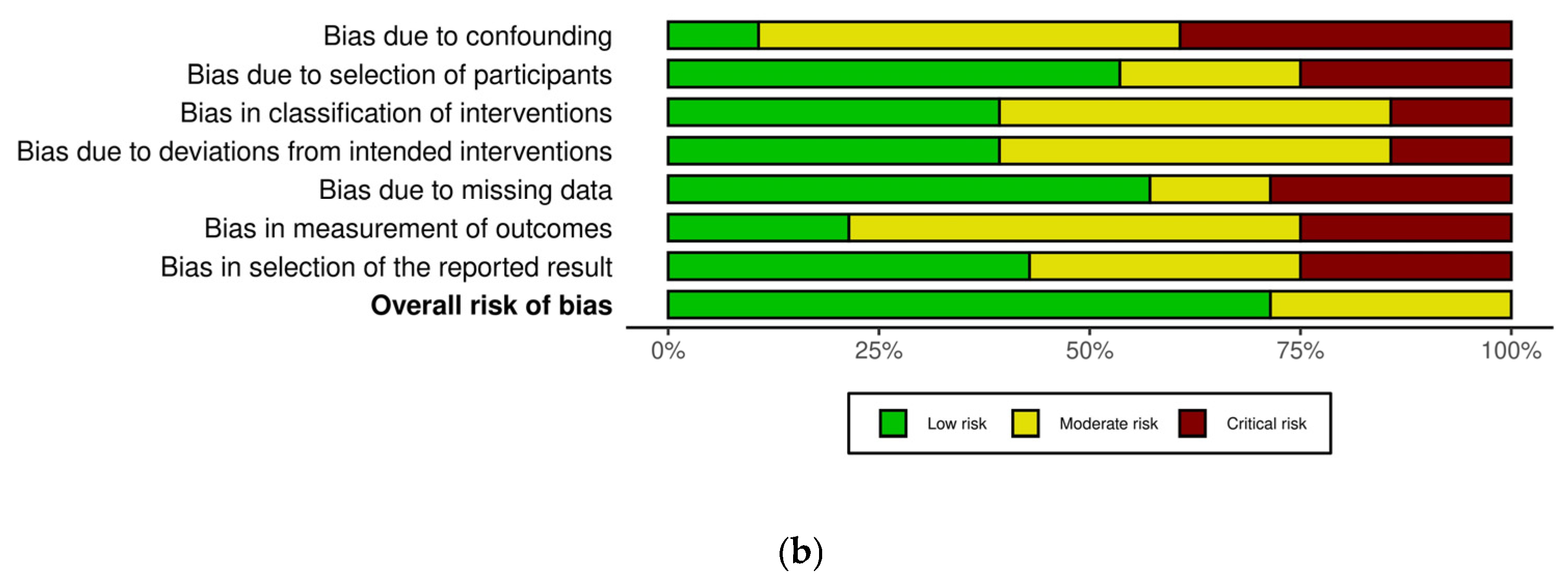

3.2. Assessment of Sexual Function in Female Patients

3.3. Timing of Questionnaire and Sexual Activity

3.4. Radical Cystectomy in Female Patients

3.5. Robot-Assisted Radical Cystectomy (RARC)

3.6. Organ-Sparing Radical Cystectomy

3.7. Type of Urinary Diversion

3.8. Radiation Therapy for Radical Cystectomy

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BC | Bladder cancer |

| MIBC | Muscle-invasive bladder cancer |

| NMIBC | Non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer |

| QoL | Quality of life |

| FSD | Female sexual dysfunction |

References

- Bizzarri, F.P.; Scarciglia, E.; Russo, P.; Marino, F.; Presutti, S.; Moosavi, S.K.; Ragonese, M.; Campetella, M.; Gandi, C.; Totaro, A.; et al. Elderly and bladder cancer: The role of radical cystectomy and orthotopic urinary diversion. Urologia 2024, 91, 500–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witjes, J.A.; Bruins, H.M.; Cathomas, R.; Compérat, E.M.; Cowan, N.C.; Gakis, G.; Hernández, V.; Espinós, E.L.; Lorch, A.; Neuzillet, Y.; et al. European Association of Urology Guidelines on Muscle-invasive and Metastatic Bladder Cancer: Summary of the 2020 Guidelines. Eur. Urol. 2021, 79, 82–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsimperis, S.; Tzelves, L.; Tandogdu, Z.; Ta, A.; Geraghty, R.; Bellos, T.; Manolitsis, I.; Pyrgidis, N.; Schulz, G.B.; Sridhar, A.; et al. Complications After Radical Cystectomy: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials with a Meta-regression Analysis. Eur. Urol. Focus 2023, 9, 920–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.; Renouf, T.; Rigby, J.; Hafeez, S.; Thurairaja, R.; Kumar, P.; Cruickshank, S.; Van-Hemelrijck, M. Female sexual function in bladder cancer: A review of the evidence. BJUI Compass 2022, 4, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Deimling, M.; Laukhtina, E.; Pradere, B.; Pallauf, M.; Klemm, J.; Fisch, M.; Shariat, S.F.; Rink, M. Radical cystectomy and urinary diversion in women: Techniques, outcomes, and challenges—A narrative review. Transl. Androl. Urol. 2022, 11, 1598–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quesada-Olarte, J.; Alvarez-Maestro, M.; Gomez-Rivas, J.; Toribio-Vazquez, C.; Aguilera Bazan, A.; Martinez-Pineiro, L. Organ-sparing cystectomy techniques: Functional and oncological outcomes, review and current recommendations. Arch. Esp. Urol. 2020, 73, 961–970. [Google Scholar]

- Gavi, F.; Foschi, N.; Fettucciari, D.; Russo, P.; Giannarelli, D.; Ragonese, M.; Gandi, C.; Balocchi, G.; Francocci, A.; Bizzarri, F.P.; et al. Assessing Trifecta and Pentafecta Success Rates between Robot-Assisted vs. Open Radical Cystectomy: A Propensity Score-Matched Analysis. Cancers 2024, 16, 1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cestari, A.; Naspro, R.; Riva, M.; Bellinzoni, P.; Nava, L.; Rigatti, P.; Guazzoni, G. Nerve-sparing laparoscopic cystectomy. Curr. Urol. Rep. 2005, 6, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riou, O.; Hennequin, C.; Khalifa, J.; Sargos, P. News and prospects on radiotherapy for bladder cancer: Is trimodal therapy becoming the gold standard? Cancer/Radiothérapie 2024, 28, 623–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palermo, G.; Bizzarri, F.P.; Scarciglia, E.; Sacco, E.; Seyed, K.M.; Russo, P.; Gavi, F.; Giovanni, B.F.; Rossi, F.; Campetella, M.; et al. The mental and emotional status after radical cystectomy and different urinary diversion orthotopic bladder substitution versus external urinary diversion after radical cystectomy: A propensity score-matched study. Int. J. Urol. 2024, 31, 1423–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modh, R.A.; Mulhall, J.P.; Gilbert, S.M. Sexual dysfunction after cystectomy and urinary diversion. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2014, 11, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyson, M.D.; Barocas, D.A. Quality of Life After Radical Cystectomy. Urol. Clin. N. Am. 2018, 45, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avulova, S.; Chang, S.S. Role and Indications of Organ-Sparing “Radical” Cystectomy. Urol. Clin. N. Am. 2018, 45, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.B.; Crowell, K.; Woods, M.E.; Wallen, E.M.; Pruthi, R.S.; Nielsen, M.E.; Lee, C.T. Functional Outcomes Following Radical Cystectomy in Women with Bladder Cancer: A Systematic Review. Eur. Urol. Focus 2017, 3, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordström, G.M.; Nyman, C.R. Male and Female Sexual Function and Activity Following Ileal Conduit Urinary Diversion. Br. J. Urol. 1992, 70, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milling, R.V.; Seyer-Hansen, A.-D.; Graugaard-Jensen, C.; Jensen, J.B.; Kingo, P.S. Female Sexual Function After Radical Cystectomy: A Cross-sectional Study. Eur. Urol. Open Sci. 2024, 70, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zippe, C.D.; Raina, R.; Shah, A.D.; Massanyi, E.Z.; Agarwal, A.; Ulchaker, J.; Jones, S.; Klein, E. Female sexual dysfunction after radical cystectomy: A new outcome measure. Urology 2004, 63, 1153–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali-El-Dein, B.; Mosbah, A.; Osman, Y.; El-Tabey, N.; Abdel-Latif, M.; Eraky, I.; Shaaban, A. Preservation of the internal genital organs during radical cystectomy in selected women with bladder cancer: A report on 15 cases with long term follow-up. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. (EJSO) 2013, 39, 358–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Bahnasawy, M.S.; Osman, Y.; El-Hefnawy, A.; Hafez, A.; Abdel-Latif, M.; Mosbah, A.; Ali-Eldin, B.; Shaaban, A.A. Radical cystectomy and urinary diversion in women: Impact on sexual function. Scand. J. Urol. Nephrol. 2011, 45, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, B.B.; Rasmussen, A.; Jensen, J.B. Evaluating sexual function in women after radical cystectomy as treatment for bladder cancer. Scand. J. Urol. 2015, 49, 463–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuderti, G.; Mastroianni, R.; Flammia, S.; Ferriero, M.; Leonardo, C.; Anceschi, U.; Brassetti, A.; Guaglianone, S.; Gallucci, M.; Simone, G. Sex-Sparing Robot-Assisted Radical Cystectomy with Intracorporeal Padua Ileal Neobladder in Female: Surgical Technique, Perioperative, Oncologic and Functional Outcomes. JCM 2020, 9, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements, M.B.; Beech, B.B.; Atkinson, T.M.; Dalbagni, G.M.; Li, Y.; Vickers, A.J.; Herr, H.W.; Donat, S.M.; Sjoberg, D.D.; Tin, A.L.; et al. Health-related Quality of Life After Robotic-assisted vs Open Radical Cystectomy: Analysis of a Randomized Trial. J. Urol. 2023, 209, 901–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkmer, B.G.; Gschwend, J.E.; Herkommer, K.; Simon, J.; Küfer, R.; Hautmann, R.E. Cystectomy and orthotopic ileal neobladder: The impact on female sexuality. J. Urol. 2004, 172, 2353–2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kretschmer, A.; Grimm, T.; Buchner, A.; Stief, C.G.; Karl, A. Prognostic features for quality of life after radical cystectomy and orthotopic neobladder. Int. Braz. J. Urol. 2016, 42, 1109–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philipps, L.; Porta, N.; James, N.; Huddart, R.; Hafeez, S.; Ballas, L.; Hall, E. Differences in Quality of Life and Toxicity for Male and Female Patients following Chemo(radiotherapy) for Bladder Cancer. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 35, e336–e343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N.; Rasmussen, S.E.V.P.; Haney, N.; Smith, A.; Pierorazio, P.M.; Johnson, M.H.; Hoffman-Censits, J.; Bivalacqua, T.J. Understanding Psychosocial and Sexual Health Concerns Among Women With Bladder Cancer Undergoing Radical Cystectomy. Urology 2021, 151, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cisternino, A.; Capone, L.; Rosati, A.; Latiano, C.; Sebastio, N.; Colella, A.; Cretì, G. New concept in urologic surgery: The total extended genital sparing radical cystectomy in women. Arch. Ital. Urol. Androl. 2023, 95, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roshdy, S.; Senbel, A.; Khater, A.; Farouk, O.; Fathi, A.; Hamed, E.; Denewer, A. Genital Sparing Cystectomy for Female Bladder Cancer and its Functional Outcome; a Seven Years’ Experience with 24 Cases. Indian J. Surg. Oncol. 2015, 7, 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wishahi, M.; Elganozoury, H. Survival up to 5–15 years in young women following genital sparing radical cystectomy and ne-obladder: Oncological outcome and quality of life. Single–surgeon and single–institution experience. CEJU 2015, 68, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements, M.B.; Atkinson, T.M.; Dalbagni, G.M.; Li, Y.; Vickers, A.J.; Herr, H.W.; Donat, S.M.; Sandhu, J.S.; Sjoberg, D.S.; Tin, A.L.; et al. Health-related Quality of Life for Patients Undergoing Radical Cystectomy: Results of a Large Prospective Cohort. Eur. Urol. 2021, 81, 294–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lind, A.K.; Liedberg, F.; Aljabery, F.; Bläckberg, M.; Gårdmark, T.; Hosseini, A.; Jerlström, T.; Ströck, V.; Stenzelius, K. Health-related quality of life prior to and 1 year after radical cystectomy evaluated with FACT-G and FACT-VCI questionnaires. Scand. J. Urol. 2023, 58, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henningsohn, L.; Wijkström, H.; Steven, K.; Pedersen, J.; Ahlstrand, C.; Aus, G.; Kallestrup, E.B.; Bergmark, K.; Onelöv, E.; Steineck, G. Relative Importance of Sources of Symptom-Induced Distress in Urinary Bladder Cancer Survivors. Eur. Urol. 2003, 43, 651–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenk, M.J.; Westhoff, N.; Liedl, B.; Michel, M.S.; Grüne, B.; Kriegmair, M.C. Evaluation of sexual function and vaginal prolapse after radical cystectomy in women: A study to explore an under-evaluated problem. Int. Urogynecology J. 2023, 34, 2933–2943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gacci, M.; Saleh, O.; Cai, T.; Gore, J.L.; D’eLia, C.; Minervini, A.; Masieri, L.; Giannessi, C.; Lanciotti, M.; Varca, V.; et al. Quality of life in women undergoing urinary diversion for bladder cancer: Results of a multicenter study among long-term disease-free survivors. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2013, 11, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siracusano, S.; D’ELia, C.; Cerruto, M.A.; Gacci, M.; Ciciliato, S.; Simonato, A.; Porcaro, A.; De Marco, V.; Talamini, R.; Toffoli, L.; et al. Quality of life following urinary diversion: Orthotopic ileal neobladder versus ileal conduit. A multicentre study among long-term, female bladder cancer survivors. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. (EJSO) 2019, 45, 477–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyritzis, S.I.; Hosseini, A.; Collins, J.; Nyberg, T.; Jonsson, M.N.; Laurin, O.; Khazaeli, D.; Adding, C.; Schumacher, M.; Wiklund, N.P. Oncologic, Functional, and Complications Outcomes of Robot-assisted Radical Cystectomy with Totally Intracorporeal Neobladder Diversion. Eur. Urol. 2013, 64, 734–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacchetti, A.; Caviglia, A.; Lorusso, V.; Branger, N.; Maubon, T.; Rybikowski, S.; Perri, D.; Bozzini, G.; Pignot, G.; Walz, J. Robot-assisted radical cystectomy with neobladder diversion in females: Safety profile and functional outcomes. Asian J. Urol. 2024, 11, 618–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavallée, E.; Dovey, Z.; Pathak, P.; Dey, L.; Koskela, L.R.; Hosseini, A.; Waingankar, N.; Mehrazin, R.; Sfakianos, J.; Hosseini, A.; et al. Functional and Oncological Outcomes of Female Pelvic Organ–preserving Robot-assisted Radical Cystectomy. Eur. Urol. Open Sci. 2022, 36, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badawy, A.A.; Abolyosr, A.; Mohamed, E.R.; Abuzeid, A.M. Orthotopic diversion after cystectomy in women: A single-centre experience with a 10-year follow-up. Arab. J. Urol. 2011, 9, 267–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allareddy, V.; Kennedy, J.; West, M.M.; Konety, B.R. Quality of life in long-term survivors of bladder cancer. Cancer 2006, 106, 2355–2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fokdal, L.; Høyer, M.; Meldgaard, P.; Von Der Maase, H. Long-term bladder, colorectal, and sexual functions after radical radio-therapy for urinary bladder cancer. Radiother. Oncol. 2004, 72, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, K.S.; Smith, A.B.; Eidelman, A.; Clayman, R.; Niemierko, A.; Cheng, J.S.; Matthews, J.; Drumm, M.R.; Nielsen, M.E.; Feldman, A.S.; et al. Quality of Life in Long-term Survivors of Mus-cle-Invasive Bladder Cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol.* Biol.* Phys. 2016, 96, 1028–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keles, A.; Somun, U.F.; Kose, M.; Arikan, O.; Culpan, M.; Yildirim, A. Exploring the influence of health and digital health literacy on quality of life and follow-up compliance in patients with primary non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: A prospective, single-center study. World J. Urol. 2025, 43, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stover, A.M.; Mueller, D.; Carda-Auten, J.; Hilton, A.; Tsurutis, V.; Smith, A.B. Perceived Impact on Patient Routines/Responsibilities for Surgery and a Nonsurgical Primary Treatment Option in Recurrent Low-Grade Intermediate-Risk Nonmuscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer: Findings From the ENVISION Phase 3 Trial. J. Urol. 2025, 214, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witjes, J.A.; Lebret, T.; Compérat, E.M.; Cowan, N.C.; De Santis, M.; Bruins, H.M.; Hernández, V.; Espinós, E.L.; Dunn, J.; Rouanne, M.; et al. Updated 2016 EAU Guidelines on Mus-cle-invasive and Metastatic Bladder Cancer. Eur. Urol. 2017, 71, 462–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizzarri, F.P.; Campetella, M.; Russo, P.; Marino, F.; Gavi, F.; Rossi, F.; Foschi, N.; Sacco, E. Risk factors for benign uretero-enteric anastomotic strictures after open radical cystectomy and ileal conduit. Urol. J. 2024, 92, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Incrocci, L.; Jensen, P.T. Pelvic Radiotherapy and Sexual Function in Men and Women. J. Sex. Med. 2013, 10, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pederzoli, F.; Campbell, J.D.; Matsui, H.; Sopko, N.A.; Bivalacqua, T.J. Surgical Factors Associated With Male and Female Sexual Dysfunction After Radical Cystectomy: What Do We Know and How Can We Improve Outcomes? Sex. Med. Rev. 2018, 6, 469–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Study Design | Center Involved | Female Eligible Patients | Age (Median or Average) | Follow-Up | Pre RC Sexual Activity | Intervention |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Craig et al., 2004 [17] | Retrospective | Single center | 34 | m54.79 | 24.2 (15–65) | 29 | RC |

| Gupta et al., 2020 [26] | Retrospective | Single center | 16 | 67.5 (60.5–79.5) | 12 | 4 | RC |

| Tyritzis et al., 2013 [36] | Retrospective | Single center | 8 | N/A | N/A | 6 | RC |

| Ali el dein et al., 2013 [18] | Retrospective | Single center | 15 | m42 | 70 (37–99) | N/A | RC |

| Siracusano et al., 2018 [35] | Prospective | Multicentric | 73 | 67 (44–86) ON 67 (44–86) IC | 43 (16–138) ON 54 (6–153) IC | N/A | RC |

| Pacchetti et al., 2024 [37] | Retrospective | Multicentric | 22 | 62 (57–66) | 29 (16–44) | 15 | RC |

| Lavallèè et al., 2021 [38] | Retrospective | Multicentric | 23 | 54 (34–79) | 20 (7–151) | 23 | RC |

| Milling et al., 2024 [16] | Retrospective | N/A | 289 | 72 (65–75) | N/A | 117 | RC |

| Cisternino et al., 2023 [27] | Retrospective | Single center | 14 | 57.6 (30–65) | N/A | N/A | RC |

| Wenk et al., 2013 [33] | Retrospective | Single center | 322 | m65.89 | N/A | N/A | RC |

| Gacci et al., 2013 [34] | Retrospective | Multicentric | 41 | m67.3 | 60.1 (36–122) | N/A | RC |

| Kretschmer et al., 2016 [24] | Retrospective | Single center | 19 | N/A | m48 | N/A | RC |

| Roshdy et al., 2015 [28] | Retrospective | Single center | 70 | 51 (45–60) | 48 (36–58) | 24 | RC |

| Wishahi et al., 2015 [29] | Retrospective | Single center | 30 | m39.4 | N/A | 13 | RC |

| Tuderti et al., 2020 [21] | Retrospective | Single center | 11 | m47.1 | 28 (14–51) | 11 | RC |

| Badawy et al., 2021 [39] | Retrospective | Single center | 78 | 42.4 (36–58) | m62 | 78 | RC |

| Clements et al., 2022 [30] | Prospective | Single center | 88 | N/A | m24 | N/A | RC |

| Clements et al., 2023 [22] | Retrospective | Single center | 15 | N/A | m24 | N/A | RC |

| Lind et al., 2023 [31] | Prospective | Multicentric | 40 | 69.5 (46–87) | 12 | 40 | RC |

| Philips et al., 2023 [25] | Prospective | Single center | 85 | N/A | 60 | 25 | RC |

| Henningsohn et al., 2003 [32] | Retrospective | Multicentric | 91 | m65.0 | N/A | N/A | RC |

| Fodkal et al., 2004 [41] | Retrospective | Single center | 16 | N/A | 29 (18–102) | 7 | RT |

| Mak et al., 2006 [42] | Prospective | Single center | 41 | 66 (59–71) | 5.6 | 29 | RT |

| Volkmer et al., 2004 [23] | Retrospective | Single center | 86 | 61 | 12 | 17 | RC |

| El-bahnasawy et al., 2011 [19] | Retrospective | Single center | 73 | 52.3 ± 6.5 | N/A | 73 | RC |

| Both et al., 2014 [20] | Retrospective | Single center | 71 | 67 (39–91) | N/A | 41 | RC |

| Nordstrom et al., 1992 [15] | Retrospective | Single center | 26 | N/A | N/A | 6 | RC |

| Allareddy et al., 2006 [40] | Retrospective | Single center | 58 | 64.4 | N/A | N/A | RT |

| Study | Type of Surgery | Type of Urinary Diversion | Organ Sparing | Vaginal Sparing | Pathological Stage (Number of Patients) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Craig et al., 2004 [17] | ORC | IC, ON, IP | N/A | 10 | T1: 20 T2: 14 |

| Gupta et al., 2020 [26] | ORC | IC and ON | N/A | 13 | T1: 8 T2-T4: 8 |

| Tyritzis et al., 2013 [36] | RARC | ON | 8 | N/A | N/A |

| Ali el dein et al., 2013 [18] | N/A | ON | 13 | N/A | T2: 14 T4: 1 |

| Siracusano et al., 2018 [35] | N/A | IC and ON | N/A | N/A | T1-Cis: 21 T2: 23 T3: 29 |

| Pacchetti et al., 2024 [37] | RARC | ON | N/A | 19 | T1-Cis: 13 T2: 3 T3: 6 |

| Lavallèè et al., 2021 [38] | RARC | IC and ON | 23 | N/A | T1-Cis: 10 T2: 13 |

| Milling et al., 2024 [16] | RARC | IC and ON | N/A | N/A | T2-T4: 86 |

| Cisternino et al., 2023 [27] | RARC and ORC | ON | N/A | N/A | T1-Cis: 8 T2: 4 T3: 2 |

| Wenk et al., 2013 [33] | N/A | IC, ON, UCS, IP | N/A | 6 | T1-Cis: 19 T2: 16 |

| Gacci et al., 2013 [34] | N/A | IC, ON, UCS | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Kretschmer et al., 2016 [24] | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Roshdy et al., 2015 [28] | ORC | ON | 24 | N/A | T1-Cis: 4 T2: 20 |

| Wishahi et al., 2015 [29] | ORC | ON | 13 | N/A | T1-Cis: 4 T2: 6 T3: 3 |

| Tuderti et al., 2020 [21] | RARC | ON | 11 | N/A | T1-Cis: 7 T3: 4 |

| Badawy et al., 2021 [39] | N/A | ON | 9 | N/A | N/A |

| Clements et al., 2022 [30] | RARC and ORC | IC and ON | N/A | 49 | N/A |

| Clements et al., 2023 [22] | RARC and ORC | IC and ON | N/A | 10 | N/A |

| Lind et al., 2023 [31] | RARC and ORC | IC, ON, UCS | N/A | N/A | T1-Cis: 12 T2: 22 T3: 5 T4: 1 |

| Philips et al., 2023 [25] | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Henningsohn et al., 2003 [32] | ORC | IC, ON, IP | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Volkmer et al., 2004 [23] | ORC | ON | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| El-bahnasawy et al., 2011 [19] | ORC | IC, ON | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Both et al., 2014 [20] | ORC | IC, ON, IP | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Nordstrom et al., 1992 [15] | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bizzarri, F.P.; Campetella, M.; Recupero, S.M.; Bellavia, F.; D’Amico, L.; Rossi, F.; Gavi, F.; Filomena, G.B.; Russo, P.; Palermo, G.; et al. Female Sexual Function After Radical Treatment for MIBC: A Systematic Review. J. Pers. Med. 2025, 15, 415. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15090415

Bizzarri FP, Campetella M, Recupero SM, Bellavia F, D’Amico L, Rossi F, Gavi F, Filomena GB, Russo P, Palermo G, et al. Female Sexual Function After Radical Treatment for MIBC: A Systematic Review. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2025; 15(9):415. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15090415

Chicago/Turabian StyleBizzarri, Francesco Pio, Marco Campetella, Salvatore Marco Recupero, Fabrizio Bellavia, Lorenzo D’Amico, Francesco Rossi, Filippo Gavi, Giovanni Battista Filomena, Pierluigi Russo, Giuseppe Palermo, and et al. 2025. "Female Sexual Function After Radical Treatment for MIBC: A Systematic Review" Journal of Personalized Medicine 15, no. 9: 415. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15090415

APA StyleBizzarri, F. P., Campetella, M., Recupero, S. M., Bellavia, F., D’Amico, L., Rossi, F., Gavi, F., Filomena, G. B., Russo, P., Palermo, G., Foschi, N., Totaro, A., Ragonese, M., Sighinolfi, M. C., Racioppi, M., Sacco, E., & Rocco, B. (2025). Female Sexual Function After Radical Treatment for MIBC: A Systematic Review. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 15(9), 415. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15090415