Simple Summary

Romania lacks comprehensive statistical data on vulvar cancer and has not been included in large multicentric European studies evaluating prognostic factors and Quality of Life for this condition. This creates a pressing need for research, especially in Romania and other Eastern European countries where patients often do not receive adequate government support. The findings of this study will lay the groundwork for future randomized controlled trials.

Abstract

Objectives: Despite the relatively high incidence of vulvar cancer, there is a noticeable lack of studies in Romania and other Eastern European countries focused on evaluating the long-term oncological outcomes and Quality of Life (QoL) for patients with this condition. Methods: A total of 91 patients were included in the study. The first objective was to evaluate the 5-year overall survival (OS) in patients with vulvar cancer at International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stages IA-IVA who underwent surgery, ±adjuvant radiotherapy (RT). Additionally, the study aimed to identify prognostic factors that could either positively or negatively influence survival outcomes in these patients. The second objective was to assess the QoL, conducted using validated questionnaires issued by the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, specifically the QLQ-CX30 and QLQ-VU34. Results: The patients had an average age of 67.7 years (38–91). At the time of assessment, 51.6% of the patients were alive. Additionally, the 5-year OS was reported at 45%. The multivariate analysis indicated that age ≤ 50 years (p < 0.03), FIGO stage IB (p < 0.007), and tumor differentiation grade I (p < 0.01) were associated with improved survival rates. Conversely, age > 80 years (p < 0.05), FIGO stages IIIB (p < 0.01) and IIIC (p < 0.06), tumor size > 5 cm (p < 0.02), positive resection margins (p < 0.03), lymph node metastasis (p < 0.06), and pelvic exenteration (p < 0.002) were identified as independent negative prognostic factors. Of the 47 living patients, 32 completed the QoL questionnaires. The respondents reported a decent overall QoL score of 65.3. However, treatment-specific symptoms, such as vulvar scarring, vulvar swelling, groin lymphedema, and leg lymphedema, had a negative impact on QoL. Consequently, functional symptoms like fatigue, pain, and sleep disturbances persisted, leading to a body image perception score of 33.7 on a scale from 0 to 100. Conclusions: This study highlights decent OS and QoL outcomes. It is important to note that vulvar cancer primarily affects older women. In this study, 51.6% of patients were over 70 years old at the time of surgery. Consequently, the 5-year OS of 45% could not be attributed solely to oncological factors, as most of these patients did not die from recurrences but rather from associated comorbidities. The findings of this study provide a foundation for future randomized controlled trials aimed at further enhancing vulvar cancer patients’ care and outcomes.

1. Introduction

Vulvar cancer is the fourth most common gynecological cancer, accounting for 5–8% of all gynecological malignancies, typically affecting postmenopausal women [1]. Approximately 65% of these cases are found in high-income countries [2]. According to the latest Globocan statistics, the global incidence of vulvar cancer is estimated at 45 cases per 100,000 women, with a mortality rate of 17.4 deaths per 100,000 women [3,4]. In Romania, the prevalence rate stands at 14.4 cases per 100,000 women [5]. Vulvar cancer can develop via two primary pathways: one associated with human papillomavirus (HPV) and another that occurs independently of HPV. The HPV-independent pathway is more commonly observed in older women [6]. HPV infection can result in the development of precancerous lesions, and if left untreated, approximately 80% can progress to invasive disease [7]. Other risk factors for the development of vulvar cancer include advancing age, cigarette smoking, inflammatory disorders affecting the vulva, and compromised immune function [6].

Squamous cell carcinomas make up 90% of all cancerous vulvar tumors, with about 50% of these cases asymptomatic [8]. According to the SEER database [6], 5-year overall survival (OS) rates differ by International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics [9] (FIGO) stage: 86% for localized disease (stages I–II), 57% for regional or locally advanced disease (stages III–IVA), and 17% for distant metastasis (stage IVB) [6]. In many higher-income countries, when measured, the estimated 5-year OS is about 50% to 70% [2,10].

The treatment approach is determined by the histological characteristics of the disease, its stage, and the patient’s overall performance status. This may include options such as surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and supportive care aimed at palliative management [11]. Patients diagnosed at an early stage of the disease are typically treated with either a wide local excision or a modified radical vulvectomy, which may include unilateral or bilateral sentinel lymph node biopsies (SLNB) or inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy [12,13]. The latter mentioned is often needed, particularly in cases where the tumor exceeds 4 cm, multiple invasive lesions are present, or there is a suspicion of inguinal lymph node involvement based on clinical or radiological findings [4,14]. A complete inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy involves the surgical excision of all lymph node-containing fatty tissue located in the superficial inguinal and deep femoral regions, specifically medial to the fossa ovalis [15]. However, approximately 30% of patients present with locally advanced disease that has spread to nearby organs and/or lymph nodes (LNs) [16]. The key risk factors associated with nodal metastasis include clinical nodal status, age, differentiation grade, tumor stage and size, the depth of stromal invasion, and the occurrence of lymphovascular space invasion (LVSI) [17]. In contrast, evidence on recurrence patterns in vulvar cancer is scarce, with most recurrences typically occurring within the vulvar area [8]. For these individuals, more extensive procedures, such as pelvic exenteration (PE), may be required to achieve clear resection margins. In cases of recurrent vulvar cancer, particularly after initial chemoradiation, PE remains the only treatment option that could provide a curative chance for select patients whose disease has spread to pelvic organs but not to distant sites [12].

This study aims to achieve two primary objectives. The first objective is to assess the prognostic factors that influence the 5-year OS in patients with vulvar cancer stages FIGO 2021 [9] IA-IVA undergoing surgery ± adjuvant radiation therapy (RT). The second objective is to evaluate the Quality of Life (QoL) of survivor patients through standardized questionnaires issued by the European Organization for Cancer Research and Treatment (EORTC), specifically the Quality of Life Questionnaires-QLQ-C30 [18] and QLQ-VU34 [19,20].

This study is necessary due to the absence of comparative research in Romania and other Eastern European countries. Although there are substantial studies on this topic in Central, Western, and Northern Europe, as well as in the USA and China, similar research is notably lacking in Romania and the broader Eastern European region. The only comparable study in Eastern Europe was conducted in Croatia in 2021 by Miljanovic-Spika et al. [7], which focused on prognostic factors in vulvar cancer but did not assess patients’ QoL.

2. Materials and Methods

This study received approval from our Institute’s Ethics Committee (approval code: 27499, 18 November 2024). Additionally, we obtained permission from the EORTC to use their QoL questionnaires, specifically the QLQ-VU34 [19,20] and QLQ-C30 [18]. All participating patients provided informed written consent.

2.1. Study Design and Patient Population

This retrospective observational study included 91 patients who met the inclusion criteria, treated and followed up at the First Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinic of Târgu Mureș, Romania. The authors analyzed the demographic data, clinical details, diagnosis, staging, treatment methods, disease outcomes, and survival. Patients were evaluated by a multidisciplinary team consisting of experienced gynecologic oncologists, medical oncologists, radiotherapists, pathologists, radiologists, and anesthesiologists. Each patient underwent a series of essential clinical, hematological, imaging, and pathological assessments. For select individuals, imaging techniques such as computed tomography (CT) scans, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and cysto-sigmoidoscopy were recommended.

Disease staging was determined following the FIGO 2021 classification system [9]. Treatment plans were tailored based on the disease stage, histological type, performance status, and the possibility of achieving a tumor-free resection (R0). Regular follow-ups post-treatment were advised in accordance with ESGO guidelines [4]—every three months during the first year, followed by six-month intervals until the fifth year, and then annually thereafter.

2.2. Data Assesment and Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis involved descriptive statistics (frequency, percentage, mean, median, standard deviation) and inferential statistics. The Shapiro–Wilk test assessed data distribution. The Mann–Whitney test was used for comparing two non-Gaussian data sets, while the Kruskal–Wallis test, along with Dunn’s test for multiple comparisons, was used for more than two sets. The Chi-square test evaluated associations between qualitative variables. To examine the impact of multiple variables on event timing, univariable and multivariable Cox regression analyses with hazard ratio were performed, and Kaplan–Meier curves were analyzed for survival. A significance threshold of p < 0.05 was established. Analysis was conducted using SPSS version 29.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). The lack of a prospective power analysis suggests that the study might be underpowered to detect small to moderate effect sizes. Therefore, the results should be interpreted with caution, and further research with larger, prospectively designed studies is needed to confirm these findings.

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The study included patients with either recurrent or non-recurrent vulvar cancer, confirmed through clinical evaluation, histopathology, and imaging techniques, and categorized according to the revised FIGO 2021 stages IA-IVA [1,9]. These patients underwent surgery for vulvar cancer, with or without adjuvant RT. Other types of therapies were excluded due to their limited prevalence and potential to influence the results, which were not expected to yield statistically significant outcomes. Furthermore, patients with distant metastases or synchronous cancers were also excluded (see Table 1 and Table 2).

Table 1.

The features of the 91 participants involved in the study.

Table 2.

The features of the 91 participants involved in the study (continued).

In terms of QoL assessment, only patients who had no recurrence, no known comorbidities, and agreed to participate in the study were included. Additionally, only those with a known follow-up were considered eligible. The use of complete case analysis in the QoL assessment may have reduced the sample size and statistical power, potentially limiting the generalizability of the findings.

2.4. Treatment Administered

The patients received the following treatments: Wide local excision, which involves the removal of the area containing the lesion, along with a margin of healthy tissue surrounding it. This procedure is recommended for small tumors and for older patients; hemivulvectomy (anterior, posterior, left or right), which involves the removal of a portion of the vulva along with adjacent structures; and total radical vulvectomy, which entails the complete removal of the vulva along with the surrounding soft tissues.

In cases of urethral invasion, up to 2 cm of the distal urethra was resected without significantly affecting urinary continence. Additionally, in some patients, a distal colpectomy was performed to ensure clear resection margins.

PE involved the removal of all pelvic organs, including the vulva, vagina, cervix, uterus, and bladder ± rectum, including the need for inguinofemoral and/or pelvic lymphadenectomy.

In some patients, the perineal defect was successfully covered using a V-Y flap, a rhomboid flap, or a vertical rectus abdominis myocutaneous (VRAM) flap (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Vertical rectus abdominis myocutaneous (VRAM) flap in a patient with PE.

In relation to lymphadenectomy, sentinel lymph node biopsy could not be performed due to a lack of logistical support, despite the latest recommendations [4,21]. Consequently, the approach to lymphadenectomy was determined by the proximity of the tumor margin to the median line. If the tumor margin was less than 2 cm from the median line, a unilateral inguinal–femoral lymphadenectomy was performed. In cases where the tumor margin exceeded 2 cm from the median line, a bilateral inguinal–femoral lymphadenectomy was carried out.

Deep inguinal–femoral lymphadenectomy was conducted, beneath the cribriform fascia.

Adjuvant RT was administered following the final histopathological examination, which revealed positive resection margins and LN metastases.

2.5. Quality of Life Questionnaires-QLQ-C30 and QLQ-VU34

To all alive and eligible patients who met the inclusion criteria, a postal letter was sent that included an informed consent form and a set of validated self-administered questionnaires, along with a prepaid reply envelope. Those who did not respond to the letters were contacted by phone.

The EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaire [18] comprises 30 items and serves as a fundamental tool used across various types of malignancies. It features five functional scales (physical, role, emotional, cognitive, and social), three symptom scales (fatigue, pain, and nausea/vomiting), a global health QoL scale, and six individual items that address common symptoms reported by cancer patients (dyspnea, appetite loss, sleep disturbances, constipation, and diarrhea), as well as perceived financial issues.

The Vulva Module-QLQ-VU34 [19,20], which is still under testing in Phase IV, serves as an additional questionnaire module designed to function alongside the QLQ-C30. It encompasses ten multi-item scales to evaluate various conditions, including changes in vulva skin, vulva scarring, vulva swelling, lymphedema in the groin and legs, urgency and leakage for urine and bowels, body image, sexual enjoyment, and sexually related vaginal changes. Additionally, it includes a single-item assessment focused on vulvo-vaginal discharge. The scoring method for the QLQ-VU34 follows the same fundamental principles as the QLQ-C30.

To enhance interpretation, the scales and items from the questionnaires were converted to a 0 to 100 scale following a scoring manual. This transformation standardizes the data, making it easier to understand and compare the results [18]. In the EORTC QLQ-C30, a higher score on the global QoL and functional scales indicates better functioning and improved QoL, whereas higher scores on the item and symptom scales reflect greater levels of disturbance. For the VU34, higher scores indicate more severe symptoms and poorer functioning, except for the scales measuring sexual activity and sexual satisfaction, where higher scores signify better outcomes. All statistical results are presented as raw numbers and percentages and summarized as means (standard deviation), along with the 95% confidence interval of the mean score.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics and Survey Results

Between January 2013 and January 2025, 146 patients underwent surgery for vulvar cancer at the First Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinic of Târgu Mureș, Romania. Of these, 91 met the inclusion criteria for the study. The mean age of patients was 68 years (ranging from 38 to 91); 51.6% were over 70 years old at the time of surgery, with a predominance of 63.73% from rural areas. Histological examination revealed that 86.8% of patients had squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva, while 9.8% presented with other types. Additionally, 48.3% had synchronous VIN III lesions on the final pathological report. Tumor staging according to FIGO 2021 was as follows: IA (4.4%), IB (40.6%), II (14.2%), IIIA (15.3%), IIIB (5.4%), IIIC (15.3%), and IVA (4.4%). Tumors were also grouped according to size: 1 cm (3.3%), 2 cm (16.4%), 3 cm (15.3%), 4 cm (26.3%), and 5 cm (28.5%). Regarding tumor differentiation, 30% were grade 1 (well-differentiated), 38.4% grade 2 (moderately differentiated), and 30.7% grade 3 (poorly differentiated). The depth of stromal invasion indicated that 85.7% of patients had an invasion depth greater than 1 mm, while only 12% had a depth of 1 mm or less. Additional significant findings included positive LVSI in 43.9% of cases and positive resection margins in 30.7% (Table 1 and Table 2).

One of the most significant negative prognostic variables was LN metastases, which was found in 30.7% of patients (Table 2). The two most frequent postoperative complications were wound dehiscence and lymphedema (Table 2). Though, no significant intraoperative complications were reported.

In terms of treatment, 13.1% of patients underwent surgery alone, 18.6% underwent wide local excision, 37.2% underwent hemivulvectomy (anterior, posterior, left or right), 41.7% underwent total radical vulvectomy, and 3.3% underwent PE. Concerning adjuvant therapy, 84.6% received adjuvant RT.

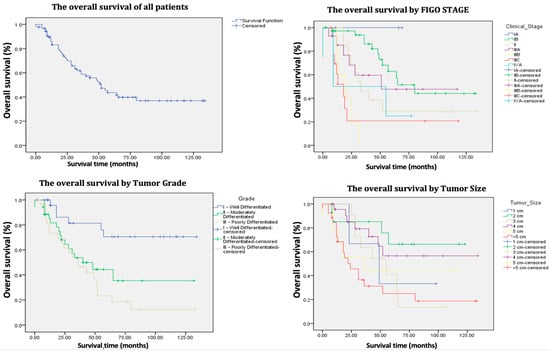

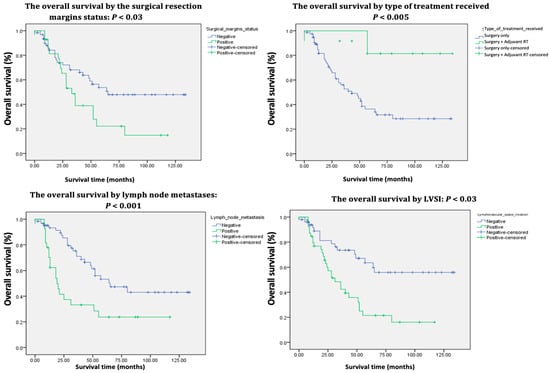

The average follow-up period for patients extended up to January 2025 and was 41.9 months (ranging from 0 to 134 months). At the time of assessment, 51.6% of the patients were alive, with a 5-year OS of 45% (Table 2, Figure 2 and Figure 3). Among the survivors, 85.1% were alive without disease, while 14.8% were alive with disease.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves of the 91 patients treated for vulvar cancer.

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves of the 91 patients treated for vulvar cancer (continued).

3.1.1. Univariate Cox Analysis (Table 1 and Table 2)

The univariate Cox analysis revealed that patients aged 50 years or younger had a significantly lower probability of death (p 0.03) and longer survival time, whereas those older than 80 years were associated with a significantly higher probability of death and shorter survival time (p = 0.03).

Furthermore, for each categorical increase in age (from 50 years or younger to 51–60, 61–70, 71–80, and >80 years), the risk of death increases by 1.599 times, which is statistically significant (p 0.002).

Regarding FIGO stage, each incremental increase in stage corresponds to a 1.373-fold increase in the risk of death, which is statistically significant (p 0.0001). Specifically, FIGO stages IIIB and IIIC were associated with significantly shorter survival rates (p 0.003 and p < 0.005, respectively). In contrast, FIGO stage IB demonstrated significantly longer survival compared to the other stages (p 0.006).

Moreover, an increase in tumor diameter by each centimeter is also associated with an elevated risk of mortality and poorer survival outcomes (p 0.01), with the worst survival rates linked to tumors larger than 5 cm (p 0.003).

In terms of tumor grade, grade I (well differentiated) is associated with longer survival (p 0.002) compared to grade III (poorly differentiated), which is associated with shorter survival (p 0.007).

Additionally, the presence of lymphovascular space invasion, positive resection margins, and lymph node metastasis were associated with a higher probability of mortality and shorter survival times, with p-values of 0.001, 0.05, and 0.002, respectively.

Patients undergoing surgery alone exhibited poorer survival rates compared to those who received adjuvant RT postoperatively (p 0.01). Moreover, PE was associated with an increased risk of mortality (p 0.03).

3.1.2. Multivariate Cox Analysis (Table 3)

In contrast to univariate analysis, which identifies multiple prognostic factors with either negative or positive significance, the multivariate analysis isolates the following favorable prognostic factors associated with a reduced risk of death and increased survival: age ≤ 50, FIGO stage IB, and tumor differentiation grade I—well differentiated, all with p-values < 0.05 (Table 3). Conversely, the following independent factors negatively influenced survival: age > 80, FIGO stages IIIB and IIIC, tumor size > 5 cm, positive resection margins, LN metastasis, and PE, all with p-values < 0.05 (Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariate Cox analysis.

Table 3.

Multivariate Cox analysis.

| Variables | p-Value | HR | 95.0% CI for OR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Age ≤ 50 | 0.03 | 0.111 | 0.014 | 0.904 |

| Age > 80 | 0.05 | 2.011 | 0.757 | 5.342 |

| FIGO stage IB | 0.007 | 0.275 | 0.107 | 0.710 |

| FIGO stage IIIB | 0.01 | 5.130 | 1.295 | 20.315 |

| FIGO stage IIIC | 0.006 | 5.532 | 1.617 | 18.923 |

| Grade I—Well Differentiated | 0.01 | 0.200 | 0.057 | 0.695 |

| Tumor size > 5 cm | 0.02 | 1.835 | 0.873 | 3.859 |

| Positive resection margins status | 0.03 | 0.319 | 0.319 | 1.918 |

| Lymph node metastasis | 0.006 | 0.069 | 0.069 | 1.042 |

| Pelvic exenteration | 0.002 | 3.019 | 3.019 | 25.310 |

HR: hazard ratio; CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio.

3.2. Results of the QoL Study

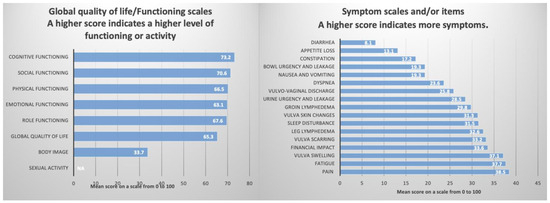

Of the 47 alive patients, 68% (n = 32) responded to the QoL questionnaires. The mean age of respondents was 66 years (range 40–79), with 75% (n = 24) receiving adjuvant RT following surgery. The patients were surveyed after a median follow-up period of 56.4 months.

3.2.1. EORTC QLQ-C30 Questionnaire

The EORTC QLQ-C30 [18] is a fundamental questionnaire widely utilized across various malignancies. The survivors reported a reasonably positive global QoL score of 65.3 (median). This result reflects the status of the patients during the week in which they were evaluated.

The functional scales assessing physical functioning, role functioning, cognitive functioning, emotional functioning, and social functioning also yielded satisfactory scores, in accordance with the overall QoL (Table 4, Figure 4).

Table 4.

The QoL of the 32 patients who answered the questionnaires.

Figure 4.

The QoL of the 32 patients who answered the EORTC QLQ-C30 and EORTC QLQ-VU34.

An important section of this questionnaire pertains to the assessment of symptoms experienced by the surveyed patients. The results for nausea, vomiting, dyspnea, appetite loss, constipation, and diarrhea were 19.3%, 23.6%, 13.1%, 17.2%, and 8.1%, respectively, indicating that these symptoms are not of significant concern. However, several symptoms and items reported had a detrimental impact on the QoL. Specifically, fatigue, pain, sleep disturbances, and financial impact were associated with scores of 37.7%, 38.5%, 31.5%, and 33.6%, respectively (Table 4, Figure 4).

3.2.2. EORTC QLQ-VU34 Questionnaire

The EORTC QLQ-VU34 [19,20] must be used in conjunction with QLQ-C30 and is designed to evaluate the specific symptoms associated with vulvar cancer. The results indicate that treatments received negatively impacted the QoL and self-image of these patients, as evidenced by a body image score of only 33.7. Furthermore, there was a complete lack of reported sexual activity, with questions 60–64 left unanswered. This may be attributable to the average age of the surveyed patients (66 years). Regarding the specific symptoms of vulvar cancer, the most concerning values were noted for vulvar swelling, vulvar scarring, leg lymphedema, and vulvar skin changes, all exceeding a score of 30.0 (Table 4 and Figure 4).

4. Discussion

Vulvar cancer is considered a rare condition; however, its incidence has been rising in recent decades, particularly among women under the age of 60 [22]. Radical surgery, particularly en bloc resection, has long been considered the primary therapeutic option despite its high complication rates and potential for significant disfigurement [23]. Taussing and Way [24] pioneered the radical vulvectomy technique, which included en bloc bilateral inguinal–femoral lymphadenectomy. Subsequently, the modified radical vulvectomy was introduced, focusing on extensive excision of the primary tumor. Over the years, the significance of inguinal–femoral lymphadenectomy—whether unilateral or bilateral—has evolved, especially with the introduction of SLN biopsy as a less invasive method for LN staging in patients with unifocal tumors under 4 cm and no suspicious groin nodes [23]. Treatment decisions for advanced primary tumors are challenging due to an inconsistent application of chemo/radiotherapy protocols for the vulva, groin, and pelvis, which vary internationally and between institutions [25]. Addressing locally advanced tumors with only radical vulvar excision often results in significant morbidity. Likewise, treatment strategies for advanced vulvar cancer are highly variable, influenced by the infrequency of cases at individual centers and continuous advancements in both surgical and radiation techniques, leaving the efficacy of these treatments somewhat ambiguous [26]. In regard to recurrences, according to the 2024 NCCN Guidelines [21] and 2023 ESGO Guidelines [4], the use of imaging techniques to identify asymptomatic distant metastases has not been shown to provide any clear benefits and is not expected to enhance survival rates, particularly due to the unfavorable prognosis and limited effectiveness of salvage treatments in patients experiencing distant recurrences [22]. Nevertheless, two months post-definitive chemoradiotherapy, at least a CT or a PET/CT should be conducted to confirm complete remission [4,21]. For vulvar recurrences, radical local excision combined with inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy is advised if no prior surgery or only SLN biopsy was performed. Adjuvant therapy indications mirror those for primary disease treatment. If surgery is not an option, external beam RT (EBRT), with or without brachytherapy or concurrent chemotherapy, is recommended [4,21]. In nodal recurrence, radical excision is preferred, with EBRT following surgery in previously untreated patients, while definitive chemoradiotherapy is suitable when surgical intervention is not viable [4,21,22].

In this study, the surgical procedures included wide local resection (18.6%), a type of hemivulvectomy (anterior, posterior, left or right) (37.2%), total radical vulvectomy (41.7%), and PE (3.3%), with a total of 84.6% of patients subsequently receiving adjuvant RT. Additionally, 68.1% of patients underwent LN dissection, with 83.8% receiving bilateral inguinal–femoral lymphadenectomy and 16.1% undergoing unilateral lymphadenectomy, consistent with findings reported by Mansouri et al. [27]. Within the entire cohort of patients who underwent surgery for vulvar cancer, additional neoadjuvant or adjuvant treatments were identified. However, to avoid biased results due to the limited number of these cases, they were excluded from the study.

4.1. Prognostic Factors and Survival

Broadly, the 5-year OS of patients with primary vulvar cancer varies between 40% and 90%, whereas the OS for patients experiencing recurrences falls between 25% and 50% [1,4,7,9,12,15,17,22,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36]. In the current study, 47 out of 91 patients (51.6%) were alive at the time of investigation, indicating a 5-year OS of 45% and a median survival time of 43 months. These results, while slightly less robust, are comparable to those reported in the earlier referenced studies (Table 1 and Table 2) (Figure 2 and Figure 3). Nevertheless, it is important to note that in the authors’ cohort of 91 patients, 47 (51.64%) were over 70 years old at the time of surgery. Consequently, the 5-year OS of 45% could not be attributed solely to oncological factors, as most of these patients did not die from recurrences but rather from associated comorbidities.

The univariate analysis reveals that survival was negatively impacted by age, FIGO stage, tumor size, tumor differentiation grade, LVSI, resection margin status, LN metastases, and the type of treatment received, all of which displayed p-values < 0.05 (Table 1 and Table 2). Conversely, the multivariate analysis exposes age ≤ 50 (p < 0.03), FIGO stage IB (p < 0.007), and tumor differentiation grade I (p < 0.01) to be linked to a decreased risk of mortality and improved survival rates (Table 3) while age > 80 (p < 0.05), FIGO stages IIIB (p < 0.01) and IIIC (p < 0.06), tumor size > 5 cm (p < 0.02), positive resection margins (p < 0.03), LN metastasis (p < 0.06), and PE (p < 0.002) were identified as independent negative prognostic factors. The results of the univariate and multivariate analyses are consistent and comparable with those of other similar studies [7,8,22,27,34,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45].

Patients who received adjuvant RT demonstrated superior survival rates compared to those who underwent only surgical procedures, with a 5-year overall survival (OS) rate of 76% (p < 0.005). This finding aligns with the research of Woelber et al. [46] and Matsumoto et al. [33]. In terms of age, our study revealed that the risk of mortality increases with each decade, contrasting with the findings of Miljanovic-Spika et al. [7], who found no statistically significant correlations. Younger women are more likely to engage in regular gynecological check-ups, which allows for earlier detection and treatment of vulvar lesions. In contrast, older women typically present with more advanced stages of the disease [43].

Despite the influence of positive resection margins and tumor size greater than 5 cm on the 5-year OS, the historical consensus remains that nodal status is the most significant independent predictor of survival and recurrence in vulvar cancer [8,47]. Baiocchi et al. [30] report that the 5-year OS for patients with positive LN ranges from 30% to 58.5%, whereas this rate increases to between 64.7% and 90.9% for individuals without LN involvement. These findings corroborate the results of the current study, which revealed a 5-year OS of 82% for patients with negative LN (Table 1). Since 62 patients had clinically involved groin nodes, they underwent full inguinal–femoral lymphadenectomy followed by adjuvant groin RT. While this treatment yielded a good response, it was associated with complications, the most common of which included wound dehiscence, lymphedema, and lymphocysts, as also demonstrated by Swift et al. [26]. The 5-year OS was 70% for those without complications (Table 1).

4.2. Quality of Life

As observed, the 5-year OS is 45%, with a median survival time of 43 months. Consequently, as many patients with vulvar cancer succeed in surviving the disease, there is an increase in the time they live with treatment-related long-term complications and sequelae. Therefore, post-treatment QoL should be given careful consideration when counseling women regarding their treatment options. Those who undergo surgery for vulvar cancer are particularly vulnerable to sexual dysfunction [48]. A recent longitudinal study revealed a notable reduction in various QoL scales [49]. In this study, nearly 30% of patients received adjuvant RT, and the authors linked the decline in QoL at least in part to the side effects associated with RT. However, treatment satisfaction and stable psychosexual health may not primarily rely on the specific treatment option chosen; rather, they are likely to be more affected by counseling that is customized to meet the patients’ individual preferences [50].

Thus, for the first time in Romania and Eastern European countries, the QoL of patients who have undergone surgery ± adjuvant RT for vulvar cancer will be presented, evaluated using the two questionnaires EORTC QLQ-C30 and EORTC QLQ-VU34. Unsurprisingly, the comparison of the current results with others is limited by the small number of available studies in the literature and the limited number of patients responding to the questionnaires. Additionally, there is significant heterogeneity regarding the therapeutic protocols applied for vulvar cancer across different countries, as well as variations in patient selection criteria, among other factors.

The patients in this study were surveyed after an average follow-up period of 56.4 months post-treatment. Out of the 47 living patients, 32 responded to the questionnaires. The respondents reported a decent overall QoL of 65.3, which is comparable to the results obtained by Novackova et al. [48], although slightly lower than those reported by Hellinga et al. [51]. The patients surveyed underwent either exclusively surgery (25%) or received adjuvant RT (75%), which further impacted their QoL.

However, symptoms specific to the treatment, including vulvar scarring, vulvar swelling, groin lymphedema, and leg lymphedema, negatively affected QoL. Consequently, functional symptoms such as fatigue, pain, and sleep disturbances persisted at an average follow-up of 56.4 months after treatment, leading to a body image perception score of only 33.7 on a scale from 0 to 100 (Table 4). Overall, the results were anticipated and aligned with findings from other studies [48,51,52,53,54,55].

Similarly to the results of Novackova et al. [48], no patients responded to questions regarding sexual functioning (Table 4) (Figure 4). This lack of response may be attributed to the average age of the responding patients (66 years), the delicate and intimate nature of the questions, the absence of a partner, or other reasons. In the study by Trott et al. [52], responses regarding sexual functioning were obtained from only 18.6% of patients, while Oonk et al. [56] received responses from 17.7% and Melo Ferreira et al. [53] from 21.4%. Common among all these studies is the finding that both QoL and sexual functioning are significantly influenced by the type of treatment administered and the average age of the patients. The implementation of targeted physical therapy interventions can play a crucial role in the effective management of lymphedema, helping to reduce swelling, improve limb function, and enhance patients’ overall QoL. Additionally, addressing psychological well-being through supportive counseling or body image therapy is essential, as it can help patients cope with emotional and psychological challenges. Integrating these supportive measures into the multidisciplinary care approach may significantly improve both physical and mental health outcomes for patients [57].

4.3. Strength and Limitations

Vulvar cancer is a rare disease. Although there are substantial studies on this topic in Central, Western, and Northern Europe, as well as in the USA and China, similar research is notably lacking in Romania and the broader Eastern European region. The only comparable study in this area was conducted in Croatia in 2021 by Miljanovic-Spika et al. [7], which focused on prognostic factors in vulvar cancer but did not assess patients’ QoL.

Thus, the originality of this study lies in its uniqueness both in Romania and across Eastern European countries. Despite the heterogeneity of the study group and the treatment administered, the analysis effectively provides a description of QoL that is comparable to findings from other studies [48,49,52,53,54,55,56]. Additionally, the identified prognostic factors align with results from similar research [1,4,7,9,12,15,17,22,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36].

The heterogeneity of the patient population and treatments, along with the lack of stratification by surgical procedure, comorbidities, or age, limits the ability to draw definitive conclusions about specific subgroups. Future research should aim to address these limitations through larger, more homogenous cohorts and detailed subgroup analyses to provide more nuanced insights.

Nevertheless, the limitations of this study primarily stem from its cross-sectional retrospective observational nature, the heterogeneity of the patient group analyzed, and the different treatments administered. Additionally, the precise timing of disease recurrence could not be accurately determined, which hampered a thorough examination, although this would certainly be of significant interest. Furthermore, the QoL study lacks a control group, such as healthy patients, and does not include a pre-treatment assessment of QoL. Moreover, the analysis did not differentiate QoL outcomes based on the type of treatment received.

5. Conclusions

The VULCAN study [8] is acknowledged as the only large multicentric European study focused on evaluating prognostic factors in patients with vulvar cancer. Notably, Romania was not included in its analysis, despite the country’s lack of comprehensive statistical data on the disease.

In the current study, 47 out of 91 patients (51.6%) were alive at the time of investigation, reflecting a 5-year OS of 45% and a median survival time of 43 months. These results, though slightly lower, are comparable to other similar studies [1,4,7,9,12,15,17,22,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36]. However, it is important to note that 51.64% of patients were over 70 years old at the time of surgery. Consequently, the OS rate could not be attributed solely to oncological factors, as most of these patients did not die from recurrences but rather from associated comorbidities.

Regarding QoL, respondents reported an good overall QoL score of 65.3, but treatment-related symptoms, such as vulvar scarring, vulvar swelling, and groin and leg lymphedema, adversely affected QoL.

This study highlights relatively favorable OS and QoL outcomes for patients who have undergone surgery ± adjuvant RT for vulvar cancer. It emphasizes the importance of early disease detection and the necessity of special attention to long-term follow-up care. The authors, who have conducted previous research on QoL [58,59], seek to underscore the critical need to consider QoL factors for not only patients with vulvar cancer but also for all gynecological oncology patients. This issue is particularly relevant in a part of Europe where these patients often do not receive adequate government support. While this study identifies key prognostic factors and highlights the importance of QoL, further research is needed to develop specific, evidence-based strategies for incorporating these findings into patient counseling and individualized follow-up plans. Future studies should focus on translating these insights into practical tools for clinical decision-making to optimize patient care and outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S.; methodology, M.S.; software, M.S., H.B., A.-M.P., C.-I.C., and D.M.C.; validation, M.E.C.; investigation, M.S., H.B., A.-M.P., S.L.K., C.-I.C., and D.M.C.; resources, M.S. and M.E.C.; writing—original draft, preparation, and editing, M.S.; supervision, M.E.C.; project administration, M.S. and M.E.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of our Institute (approval code: 27499, 18 November 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

We will provide our data for the reproducibility of this study in other centers if they are requested.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interests.

References

- Virarkar, M.; Vulasala, S.S.; Daoud, T.; Javadi, S.; Lall, C.; Bhosale, P. Vulvar Cancer: 2021 Revised FIGO Staging System and the Role of Imaging. Cancers 2022, 14, 2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Martel, C.; Plummer, M.; Vignat, J.; Franceschi, S. Worldwide Burden of Cancer Attributable to HPV by Site, Country and HPV Type. Int. J. Cancer 2017, 141, 664–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oonk, M.H.M.; Planchamp, F.; Baldwin, P.; Mahner, S.; Mirza, M.R.; Fischerová, D.; Creutzberg, C.L.; Guillot, E.; Garganese, G.; Lax, S.; et al. European Society of Gynaecological Oncology Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Vulvar Cancer—Update 2023. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2023, 33, 1023–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferlay, J.; Ervik, M.; Lam, F.; Laversanne, M.; Colombet, M.; Mery, L.; Piñeros, M.; Znaor, A.; Soerjomataram, I.; Bray, F. Statistics at a Glance, 2022 Top 5 Most Frequent Cancers Number of New Cases Number of Prevalent Cases (5-Year) 301 870 Males Females Both Sexes; Global Cancer Observatory: Lyon, France, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Koh, W.J.; Greer, B.E.; Abu-Rustum, N.R.; Campos, S.M.; Cho, K.R.; Chon, H.S.; Chu, C.; Cohn, D.; Crispens, M.A.; Dizon, D.S.; et al. Vulvar Cancer, Version 1.2017, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2017, 15, 92–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miljanović-špika, I.; Drežnjak Madunić, M.; Topolovec, Z.; Kujadin Kenjereš, D.; Vidosavljević, D. Prognostic Factors For Vulvar Cancer. Acta Clin. Croat. 2021, 60, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zapardiel, I.; Iacoponi, S.; Coronado, P.J.; Zalewski, K.; Chen, F.; Fotopoulou, C.; Dursun, P.; Kotsopoulos, I.C.; Jach, R.; Buda, A.; et al. Prognostic Factors in Patients with Vulvar Cancer: The VULCAN Study. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2020, 30, 1285–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olawaiye, A.B.; Cotler, J.; Cuello, M.A.; Bhatla, N.; Okamoto, A.; Wilailak, S.; Purandare, C.N.; Lindeque, G.; Berek, J.S.; Kehoe, S. FIGO Staging for Carcinoma of the Vulva: 2021 Revision. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2021, 155, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vulvar Cancer—Cancer Stat Facts. Available online: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/vulva.html (accessed on 29 December 2024).

- Kumar, N.; Ray, M.D.; Sharma, D.N.; Pandey, R.; Lata, K.; Mishra, A.; Wankhede, D.; Saikia, J. Vulvar Cancer: Surgical Management and Survival Trends in a Low Resource Setting. J. Egypt. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2020, 32, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valstad, H.; Eyjolfsdottir, B.; Wang, Y.; Kristensen, G.B.; Skeie-Jensen, T.; Lindemann, K. Pelvic Exenteration for Vulvar Cancer: Postoperative Morbidity and Oncologic Outcome—A Single Center Retrospective Analysis. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2023, 49, 106958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zach, D.; Åvall-Lundqvist, E.; Falconer, H.; Hellman, K.; Johansson, H.; Flöter Rådestad, A. Patterns of Recurrence and Survival in Vulvar Cancer: A Nationwide Population-Based Study. Gynecol. Oncol. 2021, 161, 748–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aznar, A.L.; Pérez-Benavente, A.; Cabrera, S.; Bebia, V.; Gil-Moreno, A.; Angeles, M.A. Inguinofemoral Lymphadenectomy Technique in 10 Steps. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2023, 33, 1823–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadducci, A.; Tana, R.; Barsotti, C.; Guerrieri, M.E.; Genazzani, A.R. Clinico-Pathological and Biological Prognostic Variables in Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Vulva. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2012, 83, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meltzer-Gunnes, C.J.; Småstuen, M.C.; Kristensen, G.B.; Tropé, C.G.; Lie, A.K.; Vistad, I. Vulvar Carcinoma in Norway: A 50-Year Perspective on Trends in Incidence, Treatment and Survival. Gynecol. Oncol. 2017, 145, 543–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olawaiye, A.B.; Cuello, M.A.; Rogers, L.J. Cancer of the Vulva: 2021 Update. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2021, 155, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaronson, N.K.; Ahmedzai, S.; Bergman, B.; Bullinger, M.; Cull, A.; Duez, N.J.; Filiberti, A.; Flechtner, H.; Fleishman, S.B.; Haes, J.C.J.M.D.; et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: A Quality-of-Life Instrument for Use in International Clinical Trials in Oncology. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1993, 85, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vulva Cancer|EORTC—Quality of Life. Available online: https://qol.eortc.org/questionnaire/qlq-vu34/ (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Froeding, L.P.; Greimel, E.; Lanceley, A.; Oberguggenberger, A.; Schmalz, C.; Radisic, V.B.; Nordin, A.; Galalaei, R.; Kuljanic, K.; Vistad, I.; et al. Assessing Patient-Reported Quality of Life Outcomes in Vulva Cancer Patients: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2018, 28, 808–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Rustum, N.R.; Yashar, C.M.; Arend, R.; Barber, E.; Bradley, K.; Brooks, R.; Campos, S.M.; Chino, J.; Chon, H.S.; Crispens, M.A.; et al. Vulvar Cancer, Version 3.2024, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2024, 22, 117–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrado, M.A.; Horta, M.; Cunha, T.M. State of the Art in Vulvar Cancer Imaging. Radiol. Bras. 2019, 52, 316–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannini, A.; D’Oria, O.; Chiofalo, B.; Bruno, V.; Baiocco, E.; Mancini, E.; Mancari, R.; Vincenzoni, C.; Cutillo, G.; Vizza, E. The Giant Steps in Surgical Downsizing toward a Personalized Treatment of Vulvar Cancer. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2022, 48, 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taussig, F.J. Cancer of the Vulva: An Analysis of 155 Cases (1911–1940). Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1940, 40, 764–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woelber, L.; Kock, L.; Gieseking, F.; Petersen, C.; Trillsch, F.; Choschzick, M.; Jaenicke, F.; Mahner, S. Clinical Management of Primary Vulvar Cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 2011, 47, 2315–2321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swift, B.E.; Khoja, L.; Matthews, J.; Croke, J.; Laframboise, S.; Leung, E.; Gien, L.T. Management of Inguinal Lymph Nodes in Locally Advanced, Surgically Unresectable, Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Vulva. Gynecol. Oncol. 2024, 187, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, H.; Zemni, I.; Sakhri, S.; Ayadi, M.A.; Boujelbene, N.; Ben Dhiab, T. Lymph Node Ratio as an Indicator of Nodal Status in the Assessment of Survival and Recurrence in Vulvar Cancer: A Cohort Study. Women’s Health 2024, 20, 17455057241285396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nooij, L.S.; Brand, F.A.M.; Gaarenstroom, K.N.; Creutzberg, C.L.; de Hullu, J.A.; van Poelgeest, M.I.E. Risk Factors and Treatment for Recurrent Vulvar Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2016, 106, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konidaris, S.; Bakas, P.; Gregoriou, O.; Kalampokas, T.; Kondi-Pafiti, A. Surgical Management of Invasive Carcinoma of the Vulva. A Retrospective Analysis and Review. Eur. J. Gynaecol. Oncol. 2011, 32, 505–508. [Google Scholar]

- Baiocchi, G.; Silva Cestari, F.M.; Rocha, R.M.; Lavorato-Rocha, A.; Maia, B.M.; Cestari, L.A.; Kumagai, L.Y.; Faloppa, C.C.; Fukazawa, E.M.; Badiglian-Filho, L.; et al. Prognostic Value of the Number and Laterality of Metastatic Inguinal Lymph Nodes in Vulvar Cancer: Revisiting the FIGO Staging System. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2013, 39, 780–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, F.; Ismail, L.; Sabbagh, A.; Hardern, K.; Owens, R.; Gozzini, E.; Soleymani Majd, H. Adjuvant Radiotherapy for Groin Node Metastases Following Surgery for Vulvar Cancer: A Systematic Review. Oncol. Rev. 2024, 18, 1389035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Survival of Vulval Cancer|Cancer Research UK. Available online: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/vulval-cancer/survival (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- Matsumoto Videira, H.; Miguel Camargo, M.; Cesar Teixeira, J.; Evangelista Santiago, A.; Bastos Eloy Costa, L.; Bhadra Vale, D. Surgery as Primary Treatment Improved Overall Survival in Vulvar Squamous Cancer: A Single Center Study with 108 Women. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2024, 294, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwish, A.; Ismail, L.; Manek, S.; Hellner, K.; Kehoe, S.; Soleymani majd, H. Prognostic Characteristics, Recurrence Patterns, and Survival Outcomes of Vulval Squamous Cell Carcinoma—A Twelve-Year Retrospective Analysis of a Tertiary Centre. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2024, 50, 108447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, B.S.; Bernard, M.E.; Lin, J.F.; Balasubramani, G.K.; Rajagopalan, M.S.; Sukumvanich, P.; Krivak, T.C.; Olawaiye, A.B.; Kelley, J.L.; Beriwal, S. Impact of Adjuvant Chemotherapy with Radiation for Node-Positive Vulvar Cancer: A National Cancer Data Base (NCDB) Analysis. Gynecol. Oncol. 2015, 137, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, X.; Guo, S.; Feng, X.; Ai, J.; Yang, J. Overall Survival Associated with Surgery, Radiotherapy, and Chemotherapy in Metastatic Vulvar Cancer: A Retrospective Cohort Study Based on the SEER Database. Cancer Pathog. Ther. 2023, 2, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palaia, I.; Bellati, F.; Calcagno, M.; Musella, A.; Perniola, G.; Panici, P.B. Invasive Vulvar Carcinoma and the Question of the Surgical Margin. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2011, 114, 120–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maggino, T.; Landoni, F.; Sartori, E.; Zola, P.; Gadducci, A.; Alessi, C.; Soldà, M.; Coscio, S.; Spinetti, G.; Maneo, A.; et al. Patterns of Recurrence in Patients with Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Vulva A Multicenter CTF Study. Cancer 2000, 89, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, M.P.M.; Hollema, H.; Emanuels, A.G.; Krans, M.; Pras, E.; Bouma, J. The Importance of the Groin Node Status for the Survival of T1 and T2 Vulval Carcinoma Patients. Gynecol. Oncol. 1995, 57, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raspagliesi, F.; Hanozet, F.; Ditto, A.; Solima, E.; Zanaboni, F.; Vecchione, F.; Kusamura, S. Clinical and Pathological Prognostic Factors in Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Vulva. Gynecol. Oncol. 2006, 102, 333–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.K.; Sugiyama, V.; Pham, H.; Gu, M.; Rutgers, J.; Osann, K.; Cheung, M.K.; Berman, M.L.; DiSaia, P.J. Margin Distance and Other Clinico-Pathologic Prognostic Factors in Vulvar Carcinoma: A Multivariate Analysis. Gynecol. Oncol. 2007, 104, 636–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahner, S.; Jueckstock, J.; Hilpert, F.; Neuser, P.; Harter, P.; De Gregorio, N.; Hasenburg, A.; Sehouli, J.; Habermann, A.; Hillemanns, P.; et al. Adjuvant Therapy in Lymph Node-Positive Vulvar Cancer: The AGO-CaRE-1 Study. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2015, 107, dju426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mack, L.C.; Hagemeier, A.; Forner, D.M. Influence of Stage and Age on Survival of Patients with Vulvar Cancer in Germany: A Retrospective Study. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e077960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muangchang, M.; Suprasert, P.; Khunamornpong, S. Clinicopathological Prognostic Factors Influencing Survival Outcomes of Vulvar Cancer. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2021, 22, 2541–2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, S.; Kumar Sharma, M.; Kaur, I.; Khurana, R.; Batra Modi, K.; Narang, R.; Mandal, A.; Dutta, S. Vulvar Carcinoma: Dilemma, Debates, and Decisions. Cancer Manag. Res. 2018, 10, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woelber, L.; Eulenburg, C.; Choschzick, M.; Kruell, A.; Petersen, C.; Gieseking, F.; Jaenicke, F.; Mahner, S. Prognostic Role of Lymph Node Metastases in Vulvar Cancer and Implications for Adjuvant Treatment. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2012, 22, 503–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, L.; Tan, L.; Zhao, X.; Zeng, F.; Xu, D. A Prognostic Nomogram Based on Lymph Node Ratio for Postoperative Vulvar Squamous Cell Carcinoma from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Database: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Ann. Transl. Med. 2020, 8, 1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novackova, M.; Halaska, M.J.; Robova, H.; Mala, I.; Pluta, M.; Chmel, R.; Rob, L. A Prospective Study in the Evaluation of Quality of Life after Vulvar Cancer Surgery. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2015, 25, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, G.L.; Jacques, R.M.; Thompson, J.; Wood, H.J.; Hughes, J.; Ledger, W.; Alazzam, M.; Radley, S.C.; Tidy, J.A. The Impact of Surgery for Vulval Cancer upon Health-Related Quality of Life and Pelvic Floor Outcomes during the First Year of Treatment: A Longitudinal, Mixed Methods Study. Psychooncology 2016, 25, 656–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trutnovsky, G.; Holter, M.; Gold, D.; Kopera, D.; Deban, J.; Misut, D.; Aust, S.; Tamussino, K.; Greimel, E. Aesthetic Outcome and Psychosexual Distress After Treatment for Vulvar High-Grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesions. J. Low. Genit. Tract Dis. 2024, 28, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellinga, J.; Te Grootenhuis, N.C.; Werker, P.M.N.; De Bock, G.H.; Van Der Zee, A.G.J.; Oonk, M.H.M.; Stenekes, M.W. Quality of Life and Sexual Functioning after Vulvar Reconstruction with the Lotus Petal Flap. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2018, 28, 1728–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trott, S.; Höckel, M.; Dornhöfer, N.; Geue, K.; Aktas, B.; Wolf, B. Quality of Life and Associated Factors after Surgical Treatment of Vulvar Cancer by Vulvar Field Resection (VFR). Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2020, 302, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Melo Ferreira, A.P.; De Figueiredo, E.M.; Lima, R.A.; Cândido, E.B.; De Castro Monteiro, M.V.; De Figueiredo Franco, T.M.R.; Traiman, P.; Da Silva-Filho, A.L. Quality of Life in Women with Vulvar Cancer Submitted to Surgical Treatment: A Comparative Study. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2012, 165, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aerts, L.; Enzlin, P.; Vergote, I.; Verhaeghe, J.; Poppe, W.; Amant, F. Sexual, Psychological, and Relational Functioning in Women after Surgical Treatment for Vulvar Malignancy: A Literature Review. J. Sex. Med. 2012, 9, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Likes, W.M.; Stegbauer, C.; Tillmanns, T.; Pruett, J. Correlates of Sexual Function Following Vulvar Excision. Gynecol. Oncol. 2007, 105, 600–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oonk, M.H.M.; van Os, M.A.; de Bock, G.H.; de Hullu, J.A.; Ansink, A.C.; van der Zee, A.G.J. A Comparison of Quality of Life between Vulvar Cancer Patients after Sentinel Lymph Node Procedure Only and Inguinofemoral Lymphadenectomy. Gynecol. Oncol. 2009, 113, 301–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Rodriguez, A.M.; De la Fuente-Costa, M.; Escalera-de la Riva, M.; Perez-Dominguez, B.; Paseiro-Ares, G.; Casaña, J.; Blanco-Diaz, M. AI-Enhanced Evaluation of YouTube Content on Post-Surgical Incontinence Following Pelvic Cancer Treatment. SSM Popul. Health 2024, 26, 101677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanca, M.; Căpîlna, D.M.; Trâmbițaș, C.; Căpîlna, M.E. The Overall Quality of Life and Oncological Outcomes Following Radical Hysterectomy in Cervical Cancer Survivors Results from a Large Long-Term Single-Institution Study. Cancers 2022, 14, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanca, M.; Căpîlna, D.M.; Căpîlna, M.E. Long-Term Survival, Prognostic Factors, and Quality of Life of Patients Undergoing Pelvic Exenteration for Cervical Cancer. Cancers 2022, 14, 2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).