Exploring the Clinical Workflow in Pharmacogenomics Clinics: An Observational Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

“Some certifications in PGx. University of Florida also had a one-year online graduate program and precision medicine”(P2, Community Pharmacist (CP))

“They don’t yet have PGx certification through the board pharmacy specialties. …. there’s an organization that’s now called the American Association of Psychiatric pharmacists…. they had a training in Psych PGx. And then I did the ASHP PGx certificate program.”(P3, Hospital Pharmacist (HP))

“Certificate PGx course through CE impact”(P4, CP)

3.2. The Role of the Interprofessional Team and the Pharmacist

“Yes, the biggest thing would be the consultation. I am actually having to interpret the results. I get this whole panel and then I have to take that and determine what does that mean on prescribing. I am forming those whole recommendations.”(P4, CP)

“There’s the lab report, but then there’s report that they’re making that’s more personalized to the patient in the medications that they’re on… And then if the patients have any meds that they’re on where the genes are kind of in that red column, the higher risk, those patients are being flagged to recommend that they have genetic counselling, but everybody else is just getting a personalized summary report and so I’ve been helping with the generation of those reports.”(P2, CP)

“Being a genetic counsellor to me, it’s very important that people understand what the test can and cannot tell them and what some of the potential risks are or secondary findings of the testing.”(P2, CP)

“So, what I do is on my consult report, it basically is a table that says the ‘here’s it’. Let’s say they were an ultra-rapid metabolizer (UM). I put there in UM and then I put what this means and some of the drugs that are affected. I try to tailor that to their current medications or conditions. I try to focus on why did the patient seek out this service in the first place.”(P4, CP)

3.3. Patient and Healthcare Education

“Many times, when they (patients) have received them (PGx results). They said I looked at it, but I didn’t know what it means.”(P3, HP)

“We have a piece in education and supporting evidence-based medicine.”(P3, HP)

“National reviewed guidance for different topics. So, we have one that’s sort of a general provider guide. We have some patient information sheets.”(P3, HP)

“I’ve done a single lecture for the pharmacogenomics in the genetic counselling graduate programs. I’ve done a few for conferences, for the Missouri Pharmacy Association’s conference in August I’m doing an introductory to pharmacogenomics. That’ll be state-wide attended by pharmacists, pharmacy techs and pharmacy students.”(P2, CP)

“We can’t bill Insurance unless we’re doing it under some kind of collaborative agreement with a physician which I haven’t gotten to the point that I wanted to set such a thing up, so all cash pay so patients when they set up an appointment with me.”(P2, CP)

“So, the biggest hurdles we’re facing are the billing.”(P4, CP)

3.4. Resources Used for Interpretation of PGx Test Results

“We use PharmGKB, Pharmvar, I use a lot of Micromedex.”(P1, HP)

“Not just the genes that have CPIC genes and then the other genes that are reported on and then I go to PharmGKB and the literature and trying to find anything else I can to help explain things for a patient.”(P2, CP)

“You have to know how to utilize your resources. When I do the consultations, I reference a lot CPIC, PharmGKB.……I always want it to be evidence-based.”(P4, CP)

“So, it’s a software program that you can put the genetic information into along with all of the patient’s drugs and it will give you information about both drug and drug- gene interactions …. It’ll give you a list and you can quickly see which ones are green, yellow, red and sub them out quickly just to figure out which might be a good option.”(P2, CP)

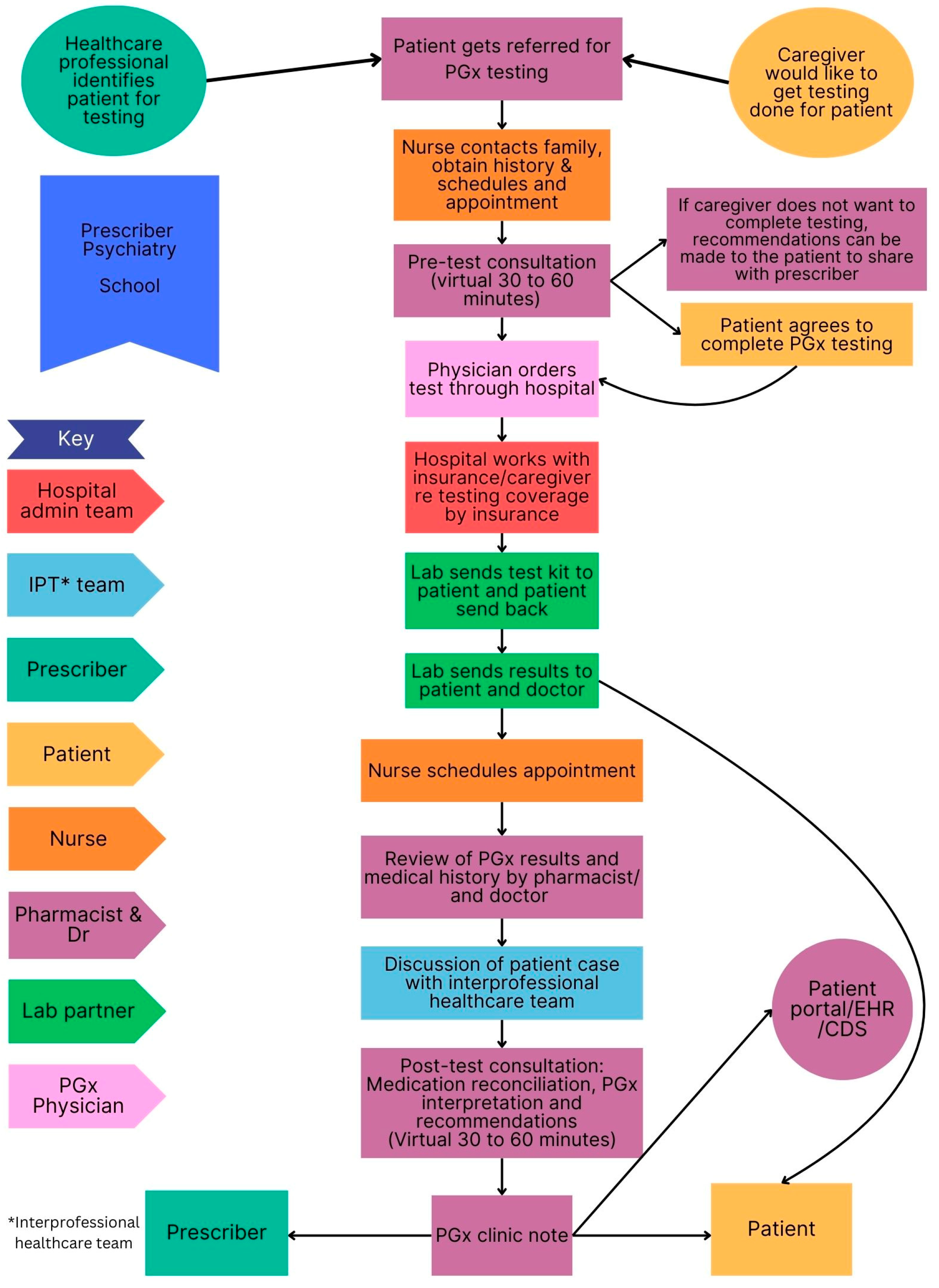

3.5. Clinical Workflow in Selected PGx Clinics

3.5.1. Similarities and Difference Among Sites

3.5.2. Pre-Test and Post-Test PGx Counselling

“They’re slotted for 1 h……... It takes 30 min, sometimes it takes the hour.”(P1, HP)

“I will normally set aside an hour for the pre-test consultation. Sometimes they don’t take that long. It just depends on how many questions the patient has and then for the post-test results I also usually set aside an hour, but those are more likely to take 30 min. I’ve had a few that take an hour.”(P2, CP)

“It’s a 15-to-30-min conversation. And then after the results come back, it’s at least a 30-min conversation.”(P4, CP)

“Here, we tried to educate our providers to provide the consenting, I have left it open that if there was someone that had a lot of questions about testing, I’d be willing to meet with them initially”(P3, HP)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CPIC | Clinical Pharmacogenomics Implementation Consortium |

| FDA | US Food and Drug Administration |

| PGx | Pharmacogenomics |

| PharmGKB | Pharmacogenomics Knowledge Base |

Appendix A

- To start, can you tell me your title and role here at (name of facility)

- How long have you been in this role?

- Could you please walk me though what happens when a patient visits your PGx clinic from first encounter to follow-up? We would like to know step-by step process and what takes place at each step, staff involved and the time it takes to complete the step.

- What is your role in this process?

- What qualifications do you have?

- What skills do you require to fulfil your position?

- What knowledge do you require to fulfil your position?

- What does the first visit entail?

- What is the typical duration of PGx consultations with patients?

- Who (what staff roles) is involved in PGx testing and interpretation?

- Who specifically performs patient counselling and medication reconciliation and at what point in the process? How does this happen—face to face or virtual?

- How do you identify patients for PGx testing?

- Do you offer any experiential learning opportunities for healthcare professionals or healthcare professional students at your facility?

- Are you involved in any research in the field of PGx at your facility?

- Are you part of any professional PGx organisations?

- What resources do you use to assist with PGx result interpretation?

- Maintain the process perspective: What, where, how, roles involved in the process

- Define the scope of the process and identify any additional steps in the process

- Identify any additional decision points, loops, reworks, bottlenecks

- Identify process time at each step and between steps: best case scenario, worst case scenario, average time

- Identify if any movement takes place between the steps, such as walking to a different floor, carrying forms to a different office, etc.

- Define external and internal customers

- Identify any obstacles/barriers/wastes in the process

- Identify any variation in the process

- What are some replicable best practices/ facilitators to the current process?

References

- Kisor, D.; Smith, H.; Grace, E.; Johnson, A.; Weitzel, K. The DNA of pharmacy education: CAPE Outcomes and Pharmacogenomics. 2015. Available online: https://www.aacp.org/sites/default/files/2017-10/The_DNA_of_Pharmacy_Education-CAPE_Outcomes_and_Pharmacogenomics_2015.pdf (accessed on 21 March 2025).

- Chart, N.; Kisor, D.; Farrell, C. Defining the role of pharmacists in medication-related genetic counseling. Pers. Med. 2021, 18, 509–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabbani, D.; Akika, R.; Wahid, A.; Daly, A.K.; Cascorbi, I.; Zgheib, N.K. Pharmacogenomics in practice: A review and implementation guide. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1189976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradley, P.; Shiekh, M.; Mehra, V.; Vrbicky, K.; Layle, S.; Olson, M.C.; Maciel, A.; Cullors, A.; Garces, J.A.; Lukowiak, A.A. Improved efficacy with targeted pharmacogenetic-guided treatment of patients with depression and anxiety: A randomized clinical trial demonstrating clinical utility. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2018, 96, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greden, J.F.; Parikh, S.V.; Rothschild, A.J.; Thase, M.E.; Dunlop, B.W.; DeBattista, C.; Conway, C.R.; Forester, B.P.; Mondimore, F.M.; Shelton, R.C.; et al. Impact of pharmacogenomics on clinical outcomes in major depressive disorder in the GUIDED trial: A large, patient- and rater-blinded, randomized, controlled study. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2019, 111, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magavern, E.F.; Kaski, J.C.; Turner, R.M.; Drexel, H.; Janmohamed, A.; Scourfield, A.; Burrage, D.; Floyd, C.N.; Adeyeye, E.; Tamargo, J.; et al. The role of pharmacogenomics in contemporary cardiovascular therapy: A position statement from the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Cardiovascular Pharmacotherapy. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacother. 2022, 8, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- US Food and Drug Administration. Table of Pharmacogenetic Associations. 2022. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/precision-medicine/table-pharmacogenetic-associations (accessed on 14 November 2024).

- Weitzel, K.W.; Duong, B.Q.; Arwood, M.J.; Owusu-Obeng, A.; Abul-Husn, N.S.; Bernhardt, B.A.; Decker, B.; Denny, J.C.; Dietrich, E.; Gums, J.; et al. A stepwise approach to implementing pharmacogenetic testing in the primary care setting. Pharmacogenomics 2019, 20, 1103–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicali, E.J.; Lemke, L.; Al Alshaykh, H.; Nguyen, K.; Cavallari, L.H.; Wiisanen, K. How to implement a pharmacogenetics service at your institution. J. Am. Coll. Clin. Pharm. 2022, 5, 1161–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haga, S.B. The critical role of pharmacists in the clinical delivery of pharmacogenetics in the U.S. Pharmacy 2023, 11, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gammal, R.S.; Lee, Y.M.; Petry, N.J.; Iwuchukwu, O.; Hoffman, J.M.; Kisor, D.F.; Empey, P.E. Pharmacists leading the way to precision medicine: Updates to the core pharmacist competencies in genomics. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2022, 86, 8634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, M.E.; Parvez, M.M.; Shin, J.G. Clinical implementation of pharmacogenomics for personalized precision medicine: Barriers and solutions. J. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 106, 2368–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhaddad, Z.A.; AlMousa, H.A.; Younis, N.S. Pharmacists’ knowledge, and insights in implementing pharmacogenomics in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klomp, S.D.; Manson, M.L.; Guchelaar, H.J.; Swen, J.J. Phenoconversion of Cytochrome P450 metabolism: A systematic review. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arwood, M.J.; Dietrich, E.A.; Duong, B.Q.; Smith, D.M.; Cook, K.; Elchynski, A.; Rosenberg, E.I.; Huber, K.N.; Nagoshi, Y.L.; Wright, A.; et al. Design and early implementation successes and challenges of a pharmacogenetics consult clinic. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zgheib, N.K.; Patrinos, G.P.; Akika, R.; Mahfouz, R. Precision medicine in low- and middle-income countries. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 107, 29–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.R. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. Am. J. Eval. 2006, 27, 237–246. [Google Scholar]

- Nowell, L.S.; Norris, J.M.; White, D.E.; Moules, N.J. Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2017, 16, 1609406917733847. [Google Scholar]

- Mack, N.; Woodsong, C.; Macqueen, K.M.; Guest, G.; Namey, E. Qualitative Research Methods: A Data Collectors Field Guide; Family Health International: Durham, NC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Antonacci, G.; Lennox, L.; Barlow, J.; Evans, L.; Reed, J. Process mapping in healthcare: A systematic review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 342. [Google Scholar]

- George, M.; Rowlands, D.; Price, M.; Maxey, J. The Lean Six Sigma Pocket Toolbook: A Quick Reference Guide to Nearly 100 Tools for Improving Process Quality, Speed and Complexity; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- BenGrahamCorporation. The Key to Good Process Mapping. 2006. Available online: http://www.worksimp.com/articles/key-to-process-mapping.htm (accessed on 13 November 2024).

- Clinical Pharmacogenomics Implementation Consortium. 2024. Available online: https://cpicpgx.org/ (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Arwood, M.J.; Chumnumwat, S.; Cavallari, L.H.; Nutescu, E.A.; Duarte, J.D. Implementing pharmacogenomics at your institution: Establishment and overcoming implementation challenges. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2016, 9, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, J.K.; Aquilante, C.L.; Dunnenberger, H.M.; Gammal, R.S.; Funk, R.S.; Aitken, S.L.; Bright, D.R.; Coons, J.C.; Dotson, K.M.; Elder, C.T.; et al. Precision pharmacotherapy: Integrating pharmacogenomics into clinical pharmacy practice. J. Am. Coll. Clin. Pharm. 2019, 2, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Morris, S.A.; Nguyen, D.G.; Morris, V.; Mroz, K.; Kwange, S.O.; Patel, J.N. Integrating pharmacogenomic results in the electronic health record to facilitate precision medicine at a large multisite health system. JACCP 2024, 7, 845–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ausi, Y.; Barliana, M.I.; Postma, M.J.; Suwantika, A.A. One step ahead in realizing pharmacogenetics in low- and middle-income countries: What should we do? J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2024, 17, 4863–4874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. The Ethical, Legal and Social Implications of Pharmacogenomics in Developing Countries: Report of an International Group of Experts. 2007. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/43669/9789241595469_eng.pdf;jsessionid=D498BA8178B3BDE1FAF51BE5B0C8B738?sequence=1 (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Stratton, T.P.; Olson, A.W. Personalizing personalized medicine: The confluence of pharmacogenomics, a person’s medication experience and ethics. Pharmacy 2023, 11, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, L.H.; Sherburn, I.A.; Gaff, C.; Taylor, N.; Best, S. Structured approaches to implementation of clinical genomics: A scoping review. Genet. Med. 2022, 24, 1415–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Description | Hospital | Community | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site A | Site C | Site B | Site D | |

| Patient counselling performed by pharmacist | ||||

| Pre-test counselling | x | x | x | |

| Post-test counselling | x | x | x | x |

| Virtual | x | x | x | x |

| Face-to-face | x | |||

| PGx testing method | ||||

| Saliva/buccal swab | x | x | x | |

| Phlebotomy | x | |||

| Payment method | ||||

| Out of pocket | x | x | x | |

| Insurance | x | x | x | |

| Other | x | |||

| Involvement of healthcare team | ||||

| Pharmacist only | x | x | ||

| Pharmacist and physician | x | |||

| Interprofessional team (pharmacist, physician, nurse, specialists, laboratory personnel) | x | x | ||

| Distribution of PGx results | ||||

| Electronic health records | x | x | x | |

| Physician | x | x | x | |

| Patient | x | x | x | x |

| Discussion Points | Description | Results from Interviews/Observations |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-test counselling | ||

| Discuss reason for referral or need for PGx testing | Referrals may be from specialists, school, physician, patient self-referral, pharmacy technicians or community healthcare workers. |

[Patient discussions appeared patient-centred) |

| History taking and medication reconciliation | Conducted through interaction with healthcare professional (pharmacist, nurse, patient/caregiver), and medical records. |

|

| Ask relevant questions related to symptoms, current medicines and concerns with past medication, including challenges and effectiveness. |

[At Site A, a nurse requests all the patient history for the physician and pharmacists and meets with the patient before a pre-test counselling session.] | |

| Family history (e.g., family history of cholesterol). |

| |

| Discussion with patient on what a PGx test is and available options so informed decisions can be made | A tool to optimize medicine and dosage. What the test can and cannot tell you and possibly secondary/incidental findings. Limitations of PGx tests. | [During the patient counselling session, the researcher observed that the physician and pharmacist emphasized that PGx is only a tool to optimize patient outcome. Limitations of the test were also discussed; there might be insufficient evidence to support recommendations due to poor quality of research, e.g., trial design.] |

| Discuss the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic process | Similar to explaining in post-test counselling. | [The physician and pharmacist communicated in a way that the patient understood. Discussion on pharmacokinetics and the role of drug metabolism. Discussed pharmacodynamics results and what they mean. Physician highlighted whether there is insufficient evidence to make an evidence-based recommendation. Lastly, drug–gene interaction table lists were shown. Discussion on, for example, which pain medication to avoid considering patient results, if applicable. Mentioned HLA genes that may cause allergic reaction.] |

| PGx terminology | Appropriate terminology should be used that is understandable for patients. | [During the researcher’s observation of patient consultations, the physician described the meaning of an intermediate, poor, normal and rapid metabolizer.] |

| Costs | Discussion on method of payment. | [PGx testing can be paid by insurance, by the patient or covered by the hospital due to service to the country (Site C only).] |

| Method of testing | Buccal cheek swab Phlebotomy | [Patient can either receive the saliva test kit in the post or a pharmacist can perform a cheek swab.] [Only Site C uses phlebotomy for PGx testing.] |

| Ethical and legal implications | Patients need to give permission to conduct the testing, and provide healthcare professionals access to medical records |

[Pharmacists work closely with physicians and the patient to access the necessary patient information while maintaining ethical and legal considerations.] |

| Post-test counselling | ||

| Interpretation of test results | Discuss clinically actionable findings, drug–gene interactions, the implications and relevance to current medicines. Also highlight possible future implications and drug–drug interactions. | [The physician and pharmacist communicated in a way that the patient understood. Discussion on pharmacokinetics and the role of drug metabolism. Discussed pharmacodynamics results and what they mean. Physician highlighted whether there is insufficient evidence to make an evidence-based recommendation. The two actionable genes (CYP2C19 and CYP2D6) based on the patient’s current medication list were discussed. Lastly, drug–gene interaction table lists were shown. Discussion on, for example, which pain medication to avoid considering patients results, if applicable. Mentioned HLA genes that may cause allergic reaction.]

|

| Discussion of other non-PGx focused concerns | Discuss and address any other concerns the patient might have. | [How and when to take iron supplements. When to take the different formulations of methylphenidate.] |

| Knowledge re-check | Re-check the patient’s understanding of their results and implications. | [During observations of patient counselling sessions, the pharmacist and physician regularly asked the patient if they had any questions. Patients were overall very grateful for the information. ] |

| Limitations of results | Discuss limitations of findings. | [Laboratories reported on genes which do not have actionable recommendations; for example, some genes which are relevant to ADHD medication do not have actionable recommendations. These limitations were discussed with the patients.] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Keuler, N.; McCartney, J.; Coetzee, R.; Crutchley, R. Exploring the Clinical Workflow in Pharmacogenomics Clinics: An Observational Study. J. Pers. Med. 2025, 15, 146. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15040146

Keuler N, McCartney J, Coetzee R, Crutchley R. Exploring the Clinical Workflow in Pharmacogenomics Clinics: An Observational Study. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2025; 15(4):146. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15040146

Chicago/Turabian StyleKeuler, Nicole, Jane McCartney, Renier Coetzee, and Rustin Crutchley. 2025. "Exploring the Clinical Workflow in Pharmacogenomics Clinics: An Observational Study" Journal of Personalized Medicine 15, no. 4: 146. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15040146

APA StyleKeuler, N., McCartney, J., Coetzee, R., & Crutchley, R. (2025). Exploring the Clinical Workflow in Pharmacogenomics Clinics: An Observational Study. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 15(4), 146. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15040146