Efficacy and Safety of Omalizumab and Dupilumab in Pediatric Patients with Skin Diseases: An Observational Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Dosing

2.2. Administered Questionnaire

2.2.1. UAS7

2.2.2. EASI Score

2.2.3. NRS

2.2.4. c-DLQI

2.2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

3.2. Omalizumab in CSU

3.3. Dupilumab in AD

3.4. Safety

4. Discussion

4.1. Efficacy and Safety of Omalizumab

4.2. Efficacy and Safety of Dupilumab

4.3. Strength and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ogulur, I.; Pat, Y.; Ardicli, O.; Barletta, E.; Cevhertas, L.; Fernandez-Santamaria, R.; Huang, M.; Bel Imam, M.; Koch, J.; Ma, S.; et al. Advances and highlights in biomarkers of allergic diseases. Allergy 2021, 76, 3659–3686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licari, A.; Manti, S.; Marseglia, A.; De Filippo, M.; De Sando, E.; Foiadelli, T.; Marseglia, G.L. Biologics in Children with Allergic Diseases. Curr. Pediatr. Rev. 2020, 16, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fricke, J.; Ávila, G.; Keller, T.; Weller, K.; Lau, S.; Maurer, M.; Zuberbier, T.; Keil, T. Prevalence of chronic urticaria in children and adults across the globe: Systematic review with meta-analysis. Allergy 2020, 75, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bylund, S.; von Kobyletzki, L.B.; Svalstedt, M.; Svensson, Å. Prevalence and Incidence of Atopic Dermatitis: A Systematic Review. Acta Derm.-Venereol. 2020, 100, adv00160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holgate, S.; Casale, T.; Wenzel, S.; Bousquet, J.; Deniz, Y.; Reisner, C. The anti-inflammatory effects of omalizumab confirm the central role of IgE in allergic inflammation. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2005, 115, 459–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xolair (Omalizumab) Prescribing Information. Available online: https://www.gene.com/download/pdf/xolair_prescribing.pdf (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Caffarelli, C.; Paravati, F.; El Hachem, M.; Duse, M.; Bergamini, M.; Simeone, G.; Barbagallo, M.; Bernardini, R.; Bottau, P.; Bugliaro, F.; et al. Management of chronic urticaria in children: A clinical guideline. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2019, 45, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harb, H.; Chatila, T.A. Mechanisms of Dupilumab. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2020, 50, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupixent (Dupilumab) Prescribing Information. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/health/documents/community-register/2021/20210111150156/anx_150156_it.pdf (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Davis, D.M.R.; Drucker, A.M.; Alikhan, A.; Bercovitch, L.; Cohen, D.E.; Darr, J.M.; Eichenfield, L.F.; Frazer-Green, L.; Paller, A.S.; Schwarzenberger, K.; et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis in adults with phototherapy and systemic therapies. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2024, 90, e43–e56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manti, S.; Licari, A. How to obtain informed consent for research. Breathe 2018, 14, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawro, T.; Ohanyan, T.; Schoepke, N.; Metz, M.; Peveling-Oberhag, A.; Staubach, P.; Maurer, M.; Weller, K. The Urticaria Activity Score-Validity, Reliability, and Responsiveness. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2018, 6, 1185–1190.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanifin, J.M.; Thurston, M.; Omoto, M.; Cherill, R.; Tofte, S.J.; Graeber, M. The eczema area and severity index (EASI): Assessment of reliability in atopic dermatitis. EASI Evaluator Group. Exp. Dermatol. 2001, 10, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puelles, J.; Fofana, F.; Rodriguez, D.; Silverberg, J.I.; Wollenberg, A.; Dias Barbosa, C.; Vernon, M.; Chavda, R.; Gabriel, S.; Piketty, C. Psychometric validation and responder definition of the sleep disturbance numerical rating scale in moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. Br. J. Dermatol. 2022, 186, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias-Barbosa, C.; Matos, R.; Vernon, M.; Carney, C.E.; Krystal, A.; Puelles, J. Content validity of a sleep numerical rating scale and a sleep diary in adults and adolescents with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. J. Patient-Rep. Outcomes 2020, 4, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holme, S.A.; Man, I.; Sharpe, J.L.; Dykes, P.J.; Lewis-Jones, M.S.; Finlay, A.Y. The Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index: Validation of the cartoon version. Br. J. Dermatol. 2003, 148, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agache, I.; Rocha, C.; Pereira, A.; Song, Y.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Solà, I.; Beltran, J.; Posso, M.; Akdis, C.A.; Akdis, M.; et al. Efficacy and safety of treatment with omalizumab for chronic spontaneous urticaria: A systematic review for the EAACI Biologicals Guidelines. Allergy 2021, 76, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Xiao, X.; Qin, D.; Cao, W.; Wang, L.; Xi, M.; Zou, Z.; Yang, Q.; Chen, S.; Liu, H.; et al. Temporal, Drug Dose, and Sample Size Trends in the Efficacy of Omalizumab for Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria: A Cumulative Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2024, 2024, 8202476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tharp, M.D.; Bernstein, J.A.; Kavati, A.; Ortiz, B.; MacDonald, K.; Denhaerynck, K.; Abraham, I.; Lee, C.S. Benefits and Harms of Omalizumab Treatment in Adolescent and Adult Patients with Chronic Idiopathic (Spontaneous) Urticaria: A Meta-analysis of “Real-world” Evidence. JAMA Dermatol. 2019, 155, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hide, M.; Park, H.-S.; Igarashi, A.; Ye, Y.M.; Kim, T.B.; Yagami, A.; Roh, J.; Lee, J.H.; Chinuki, Y.; Youn, S.W.; et al. Efficacy and safety of omal- izumab in Japanese and Korean patients with refractory chronic spontaneous urticaria. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2017, 87, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caminiti, L.; Galletta, F.; Foti Randazzese, S.; Barraco, P.; Passanisi, S.; Gambadauro, A.; Crisafulli, G.; Valenzise, M.; Manti, S. Early Assessment of Efficacy and Safety of Biologics in Pediatric Allergic Diseases: Preliminary Results from a Prospective Real-World Study. Children 2024, 11, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passanisi, S.; Arasi, S.; Caminiti, L.; Crisafulli, G.; Salzano, G.; Pajno, G.B. Omalizumab in children and adolescents with chronic spontaneous urticaria: Case series and review of the literature. Dermatol. Ther. 2020, 33, e13489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casale, T.B.; Murphy, T.R.; Holden, M.; Rajput, Y.; Yoo, B.; Bernstein, J.A. Impact of omalizumab on patient-reported outcomes in chronic idiopathic urticaria: Results from a randomized study (XTEND-CIU). J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2019, 7, 2487–2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Licari, A.; Castagnoli, R.; Denicolò, C.; Rossini, L.; Seminara, M.; Sacchi, L.; Testa, G.; De Amici, M.; Marseglia, G.L. Omalizumab in Childhood Asthma Italian Study Group. Omalizumab in Children with Severe Allergic Asthma: The Italian Real-Life Experience. Curr. Respir. Med. Rev. 2017, 13, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayres, J.; Higgins, B.; Chilvers, E.R.; Ayre, G.; Blogg, M.; Fox, H. Efficacy and tolerability of anti-immunoglobulin E therapy with omalizumab in patients with poorly controlled (moderate-to-severe) allergic asthma. Allergy 2004, 59, 701–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galletta, F.; Caminiti, L.; Lugarà, C.; Foti Randazzese, S.; Barraco, P.; D’Amico, F.; Irrera, P.; Crisafulli, G.; Manti, S. Long-Term Safety of Omalizumab in Children with Asthma and/or Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria: A 4-Year Prospective Study in Real Life. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calzari, P.; Chiei Gallo, A.; Barei, F.; Bono, E.; Cugno, M.; Marzano, A.V.; Ferrucci, S.M. Omalizumab for the Treatment of Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria in Adults and Adolescents: An Eight-Year Real-Life Experience. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 5610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blauvelt, A.; Guttman-Yassky, E.; Paller, A.S.; Simpson, E.L.; Cork, M.J.; Weisman, J.; Browning, J.; Soong, W.; Sun, X.; Chen, Z.; et al. Long-Term Efficacy and Safety of Dupilumab in Adolescents with Moderate-to-Severe Atopic Dermatitis: Results Through Week 52 from a Phase III Open-Label Extension Trial (LIBERTY AD PED-OLE). Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2022, 23, 365–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paller, A.S.; Siegfried, E.C.; Thaçi, D.; Wollenberg, A.; Cork, M.J.; Arkwright, P.D.; Gooderham, M.; Beck, L.A.; Boguniewicz, M.; Sher, L.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Dupilumab with Concomitant Topical Corticosteroids in Children 6 to 11 Years Old with Severe Atopic Dermatitis: A Randomized, Double-Blinded, Placebo-Controlled Phase 3 Trial. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2020, 83, 1282–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagan, A.D.; David, E.; Ungar, B.; Ghalili, S.; He, H.; Guttman-Yassky, E. Dupilumab Improves Clinical Scores in Children and Adolescents with Moderate to Severe Atopic Dermatitis: A Real-World, Single-Center Study. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2022, 10, 2378–2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini-Ashrafi, M.; Clayton, T.H.; Herring, M.; Herety, N.; Arkwright, P.D. Real-World Outcomes of Children Treated with Dupilumab for Moderate-to-Severe Atopic Dermatitis: A Single-Center Retrospective Observational UK Study. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2024, 49, 578–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patruno, C.; Fabbrocini, G.; Lauletta, G.; Boccaletti, V.; Colonna, C.; Cavalli, R.; Neri, I.; Ortoncelli, M.; Schena, D.; Stingeni, L.; et al. A 52-Week Multicenter Retrospective Real-World Study on Effectiveness and Safety of Dupilumab in Children with Atopic Dermatitis Aged 6 to 11 Years. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2023, 34, 2246602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napolitano, M.; Fabbrocini, G.; Neri, I.; Stingeni, L.; Boccaletti, V.; Piccolo, V.; Amoruso, G.F.; Malara, G.; De Pasquale, R.; Di Brizzi, E.V.; et al. Dupilumab Treatment in Children Aged 6–11 Years with Atopic Dermatitis: A Multicentre, Real-Life Study. Paediatr. Drugs 2022, 24, 671–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson, E.L.; Bieber, T.; Guttman-Yassky, E.; Beck, L.A.; Blauvelt, A.; Cork, M.J.; Silverberg, J.I.; Deleuran, M.; Kataoka, Y.; Lacour, J.-P.; et al. Two phase 3 trials of dupilumab versus placebo in atopic dermatitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 2335–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson, E.L.; Paller, A.S.; Siegfried, E.C.; Boguniewicz, M.; Sher, L.; Gooderham, M.J.; Beck, L.A.; Guttman-Yassky, E.; Pariser, D.; Blauvelt, A.; et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in adolescents with uncontrolled moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: A phase 3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2019, 156, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deleuran, M.; ThaçI, D.; Beck, L.A.; de Bruin-Weller, M.; Blauvelt, A.; Forman, S.; Bissonnette, R.; Reich, K.; Soong, W.; Hussain, I.; et al. Dupilumab shows long-term safety and efficacy in moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis patients enrolled in a phase 3 open- label extension study. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2019, 82, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, N.V.; Abdula, M.A.; Al Falasi, A.; Krishna, C.V. Long-term real-world experience of the side effects of dupilumab in 128 patients with atopic dermatitis and related conditions aged 6 years and above: Retrospective chart analysis from a single tertiary care center. Dermatol. Ther. 2022, 35, e15415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paller, A.S.; Simpson, E.L.; Siegfried, E.C.; Cork, M.J.; Wollenberg, A.; Arkwright, P.D.; Soong, W.; Gonzalez, M.E.; Schneider, L.C.; Sidbury, R.; et al. Dupilumab in Children Aged 6 Months to Younger than 6 Years with Uncontrolled Atopic Dermatitis: A Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet 2022, 400, 908–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | CSU | AD | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number, no. (%) | 13 (43.3) | 17 (56.7) | 30 (100) |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 14.8 (±1.55) | 14.6 (±2.49) | 14.7 (±2.1) |

| Female, no. (%) | 9 (69.2) | 10 (58.8) | 19 (63.4) |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 25.44 (±5.29) | 22.65 (±3.92) | 23.9 (±4.7) |

| Other comorbidities, no. (%) | |||

| - Asthma | 2/13 (15.3) | 9/17 (52.9) | 11/30 (36.6) |

| - Allergic rhinitis | 5/13 (38.4) | 12/17 (70.6) | 17/30 (56.7) |

| - Allergic conjunctivitis | 3/13 (23) | 11/17 (64.7) | 14/30 (46.6) |

| - Food allergy | 0/13 (0) | 2/17 (11.7) | 2/30 (6.6) |

| - Obesity | 6/13 (46.1) | 2/17 (11.7) | 8/30 (26.7) |

| - Hashimoto’s thyroiditis | 2/13 (15.3) | 1/17 (5.6) | 3/30 (20) |

| - Neurological disorders | 0/13 (0) | 2/17 (11.7) | 2/30 (6.7) |

| - Caroli’s disease | 0/13 (0) | 1/17 (5.6) | 1/30 (3) |

| Previous therapies, no (%) | |||

| - Oral corticosteroids | 2/13 (15.4) | 5/17 (29.4) | 7/30 (23.3) |

| - Antihistamines | 13/13 (100) | 10/17 (58.8) | 23/30 (76.6%) |

| - Topical corticosteroids | / | 17/17 (100) | 17/30 (56.7) |

| - Calcineurin inhibitors | / | 5/17 (29.4) | 5/30 (16.7) |

| - Ciclosporin | / | 3/17 (17.6) | 3/30 (10) |

| T0 | T16 | p T0 vs. T16 | T52 | p T0 vs. T52 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

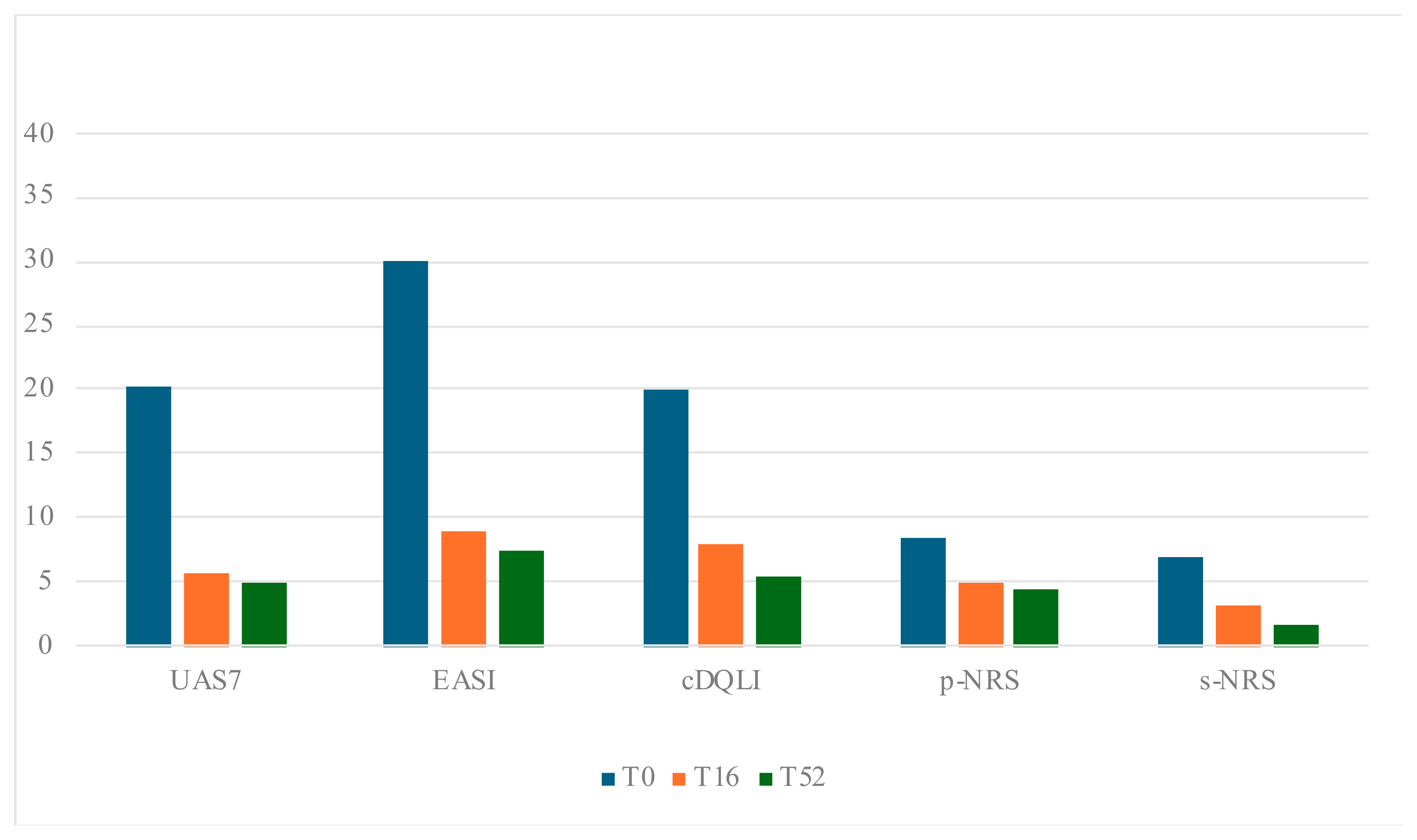

| UAS7 mean (SD) | 20.3 (±3.2) | 5.7 (±3.6) | p < 0.001 | 5 (±2.5) | p < 0.001 |

| DLQI/c-DLQI, mean (SD) | 16.8 (±3.4) | 4.4 (±3.5) | p < 0.001 | 3.30 (±1.9) | p < 0.001 |

| T0 | T16 | p T0 vs. T16 | T52 | p T0 vs. T52 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EASI, mean (SD) | 30.0 (±14.9) | 8.9 (±6.6) | p < 0.001 | 7.4 (± 5.3) | p < 0.001 |

| p-NRS, mean (SD) | 8.5 (±1.1) | 5.1 (± 2.8) | p < 0.001 | 4.5 (±2.5) | p < 0.001 |

| s-NRS, mean (SD) | 7.0 (±2.7) | 3.3 (±3.1) | p < 0.001 | 1.8 (±2.4) | p < 0.001 |

| DLQI/c-DLQI, mean (SD) | 20.1 (±6.3) | 8.1 (±4.0) | p < 0.001 | 5.5 (±3.2) | p < 0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Galletta, F.; Rizzuti, L.; Passanisi, S.; Rosa, E.; Caminiti, L.; Manti, S. Efficacy and Safety of Omalizumab and Dupilumab in Pediatric Patients with Skin Diseases: An Observational Study. J. Pers. Med. 2025, 15, 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15020064

Galletta F, Rizzuti L, Passanisi S, Rosa E, Caminiti L, Manti S. Efficacy and Safety of Omalizumab and Dupilumab in Pediatric Patients with Skin Diseases: An Observational Study. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2025; 15(2):64. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15020064

Chicago/Turabian StyleGalletta, Francesca, Ludovica Rizzuti, Stefano Passanisi, Emanuela Rosa, Lucia Caminiti, and Sara Manti. 2025. "Efficacy and Safety of Omalizumab and Dupilumab in Pediatric Patients with Skin Diseases: An Observational Study" Journal of Personalized Medicine 15, no. 2: 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15020064

APA StyleGalletta, F., Rizzuti, L., Passanisi, S., Rosa, E., Caminiti, L., & Manti, S. (2025). Efficacy and Safety of Omalizumab and Dupilumab in Pediatric Patients with Skin Diseases: An Observational Study. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 15(2), 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15020064