Three-Dimensional Printing in Hand Surgery: What Is New? A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

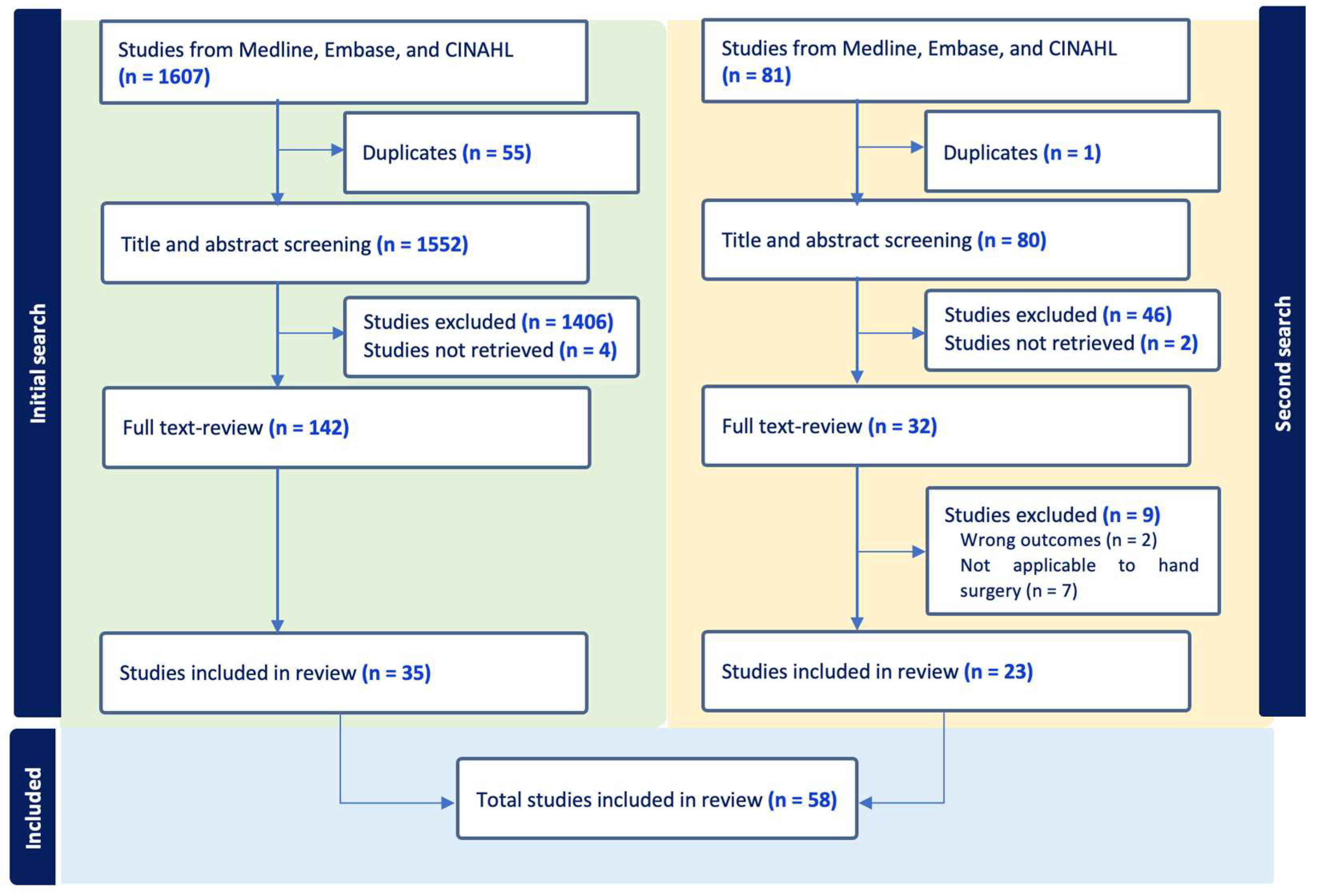

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Study Selection

2.3. Study Eligibility

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

3.2. Patient Characteristics

3.3. Clinical Uses

- (1)

- Preoperative Planning

- (2)

- Patient Education

- (3)

- Medical and Surgical Training

- (4)

- Intraoperative Assistance

- (5)

- Splinting and Casting

- (6)

- Prosthetics and Functional Reconstruction

3.4. Postoperative Outcomes

3.5. Printer Characteristics

4. Discussion

4.1. Quality of Evidence

4.2. Functional and Operative Benefits

4.3. Complications and Safety

4.4. Cost and Feasibility

4.5. Educational and Patient-Centered Value

4.6. Evidence Gaps and Future Directions

4.7. Overall Interpretation

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Karabay, N. US findings in traumatic wrist and hand injuries. Diagn. Interv. Radiol. 2013, 19, 320–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janowski, J.; Coady, C.; Catalano, L.W., 3rd. Scaphoid Fractures: Nonunion and Malunion. J. Hand Surg. 2016, 41, 1087–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizzotto, N.; Tami, I.; Tami, A.; Spiegel, A.; Romani, D.; Corain, M.; Adani, R.; Magnan, B. 3D Printed models of distal radius fractures. Injury 2016, 47, 976–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, H.S.; Park, K.J.; Kil, K.M.; Chong, S.; Eun, H.J.; Lee, T.-S.; Lee, J.-P. Minimally invasive plate osteosynthesis using 3D printing for shaft fractures of clavicles: Technical note. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2014, 134, 1551–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matter-Parrat, V.; Liverneaux, P. 3D printing in hand surgery. Hand Surg. Rehabil. 2019, 38, 338–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlachopoulos, L.; Schweizer, A.; Graf, M.; Nagy, L.; Fürnstahl, P. Three-dimensional postoperative accuracy of extra-articular forearm osteotomies using CT-scan based patient-specific surgical guides. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2015, 16, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Cai, L.; Zheng, W.; Wang, J.; Guo, X.; Chen, H. The efficacy of using 3D printing models in the treatment of fractures: A randomised clinical trial. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2019, 20, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaneyama, S.; Sugawara, T.; Sumi, M. Safe and accurate midcervical pedicle screw insertion procedure with the patient-specific screw guide template system. Spine 2015, 40, E341–E348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mok, S.W.; Nizak, R.; Fu, S.C.; Ho, K.K.; Qin, L.; Saris, D.B.; Chan, K.-M.; Malda, J. From the printer: Potential of three-dimensional printing for orthopaedic applications. J. Orthop. Transl. 2016, 6, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tam, M.D.; Laycock, S.D.; Bell, D.; Chojnowski, A. 3-D printout of a DICOM file to aid surgical planning in a 6 year old patient with a large scapular osteochondroma complicating congenital diaphyseal aclasia. J. Radiol. Case Rep. 2012, 6, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Cai, L.; Zhang, C.; Wang, J.; Guo, X.; Zhou, Y. Treatment of Die-Punch Fractures with 3D Printing Technology. J. Investig. Surg. Off. J. Acad. Surg. Res. 2018, 31, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltorai, A.E.; Nguyen, E.; Daniels, A.H. Three-Dimensional Printing in Orthopedic Surgery. Orthopedics 2015, 38, 684–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizzotto, N.; Tami, I.; Santucci, A.; Adani, R.; Poggi, P.; Romani, D.; Carpeggiani, G.; Ferraro, F.; Festa, S.; Magnan, B. 3D Printed replica of articular fractures for surgical planning and patient consent: A two years multi-centric experience. 3D Print. Med. 2015, 2, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aydin, H.E.; Kaya, I.; Aydin, N.; Kizmazoglu, C.; Karakoc, F.; Yurt, H.; Hüsemoglu, R.B. Importance of Three-Dimensional Modeling in Cranioplasty. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2019, 30, 713–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerstle, T.L.; Ibrahim, A.M.S.; Kim, P.S.; Lee, B.T.; Lin, S.J. A plastic surgery application in evolution: Three-dimensional printing. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2014, 133, 446–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suszynski, T.M.; Serra, J.M.; Weissler, J.M.; Amirlak, B. Three-dimensional printing in rhinoplasty. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2018, 141, 1383–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, W.; Tringale, K.R.; Woller, S.A.; You, S.; Johnson, S.; Shen, H.; Schimelman, J.; Whitney, M.; Steinauer, J.; Xu, W.; et al. Rapid continuous 3D printing of customizable peripheral nerve guidance conduits. Mater. Today 2018, 21, 951–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Muinck Keizer, R.J.O.; Lechner, K.M.; Mulders, M.A.M.; Schep, N.W.L.; Eygendaal, D.; Goslings, J.C. Three-dimensional virtual planning of corrective osteotomies of distal radius malunions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Strateg. Trauma Limb Reconstr. 2017, 12, 77–89. [Google Scholar]

- Inge, S.; Brouwers, L.; van der Heijden, F.; Bemelman, M. 3D printing for corrective osteotomy of malunited distal radius fractures: A low-cost workflow. BMJ Case Rep. 2018, 2018, bcr2017223996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Li, J.; Fang, T.; Zhao, J.; Pan, W.; Wang, X.; Xu, J.; Zhou, Q. Evaluation of a Three-Dimensional Printed Guide and a Polyoxymethylene Thermoplastic Regulator for Percutaneous Pedicle Screw Fixation in Patients with Thoracolumbar Fracture. Med. Sci. Monit. Int. Med. J. Exp. Clin. Res. 2020, 26, e920578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilde, F.; Hanken, H.; Probst, F.; Schramm, A.; Heiland, M.; Cornelius, C.-P. Multicenter study on the use of patient-specific CAD/CAM reconstruction plates for mandibular reconstruction. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 2015, 10, 2035–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, B.; Schanandore, J.V. Using a 3D-Printed prosthetic to improve participation in a young gymnast. Pediatr. Phys. Ther. 2021, 33, E1–E6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belloti, J.C.; Alves, B.V.P.; Faloppa, F.; Balbachevsky, D.; Netto, N.A.; Tamaoki, M.J. The malunion of distal radius fracture: Corrective osteotomy through planning with prototyping in 3D printing. Injury 2021, 52, S44–S48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belloti, J.C.; Alves, B.V.P.; Archetti, N.; Nakachima, L.R.; Faloppa, F.; Tamaoki, M.J.S. Treatment of distal radio vicious consolidation: Corrective osteotomy through 3D printing prototyping. Rev. Bras. Ortop. 2021, 56, 384–389. [Google Scholar]

- Brichacek, M.; Diaz-Abele, J.; Shiga, S.; Petropolis, C. Three-dimensional Printed Surgical Simulator for Kirschner Wire Placement in Hand Fractures. Plast. Reconstr. Surg.—Glob. Open 2018, 6, e1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casari, F.A.; Roner, S.; Fürnstahl, P.; Nagy, L.; Schweizer, A. Computer-assisted open reduction internal fixation of intraarticular radius fractures navigated with patient-specific instrumentation, a prospective case series. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2021, 141, 1425–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.J.; Lin, H.; Zhang, X.; Huang, W.; Shi, L.; Wang, D. Application of 3D-printed and patient-specific cast for the treatment of distal radius fractures: Initial experience. 3D Print. Med. 2017, 3, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.; Yin, Y.; Chen, C. Limb-salvage surgery using personalized 3D-printed porous tantalum prosthesis for distal radial osteosarcoma: A case report. Medicine 2021, 100, e27899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copeland, C.; Reyes, C.C.; Peck, J.L.; Srivastava, R.; Zuniga, J.M. Functional performance and patient satisfaction comparison between a 3D printed and a standard transradial prosthesis: A case report. Biomed. Eng. Online 2022, 21, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Khoury, G.; Libouton, X.; De Boeck, F.; Barbier, O. Use of a 3D-printed splint for the treatment of distal radius fractures: A randomized controlled trial. Orthop. Traumatol. Surg. Res. OTSR 2022, 108, 103326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exner, G.U.; Dumont, C.E.; Walker, J.; Fürnstahl, P. Cement Spacer Formed in a 3D-Printed Mold for Endoprosthetic Reconstruction of an Infected Sarcomatous Radius: A Case Report. JBJS Case Connect. 2021, 11, e20.00568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eyiis, E.; Mathijssen, N.M.; Kok, P.; Sluijter, J.; Kraan, G.A. Three-dimensional printed customized versus conventional plaster brace for trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis: A randomized controlled crossover trial. J. Hand Surg. 2023, 48, 412–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinčuk, A.; Petryla, G.; Masionis, P.; Sveikata, T.; Uvarovas, V.; Makulavičius, A. Short-term results and complications of the operative treatment of the distal radius fracture AO2R3 C type, planned by using 3D-printed models. Prospective randomized control study. J. Orthop. Surg. 2023, 31, 10225536231195127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guebeli, A.; Thieringer, F.; Honigmann, P.; Keller, M. In-house 3D-printed custom splints for non-operative treatment of distal radial fractures: A randomized controlled trial. J. Hand Surg. Eur. Vol. 2024, 49, 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honigmann, P.; Thieringer, F.; Steiger, R.; Haefeli, M.; Schumacher, R.; Henning, J. A Simple 3-Dimensional Printed Aid for a Corrective Palmar Opening Wedge Osteotomy of the Distal Radius. J. Hand Surg. 2016, 41, 464–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houdek, M.T.; Matsumoto, J.M.; Morris, J.M.; Bishop, A.T.; Shin, A.Y. Technique for 3-Dimesional (3D) Modeling of Osteoarticular Medial Femoral Condyle Vascularized Grafting to Replace the Proximal Pole of Unsalvagable Scaphoid Nonunions. Tech. Hand Up. Extremity Surg. 2016, 20, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.-Y.; Wang, T.-H.; Chang, B.-C.; Huang, C.-I.; Chou, L.-W.; Wang, S.-J.; Chen, W.-M. Printing a static progressive orthosis for hand rehabilitation. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 2021, 84, 795–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jew, N.; Lipman, J.D.; Carlson, M.G. The Use of Three-Dimensional Printing for Complex Scaphoid Fractures. J. Hand Surg. 2019, 44, 165.e1–165.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, S.Y.; Lee, S.Y.; Cho, Y.S.; Yi, S.; Seo, C.H. Clinical Utility of an Exoskeleton Robot Using Three-Dimensional Scanner Modeling in Burn Patient: A Case Report. J. Burn. Care Res. 2021, 42, 1030–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.J.; Kim, S.J.; Cha, Y.H.; Lee, K.H.; Kwon, J.Y. Effect of personalized wrist orthosis for wrist pain with three-dimensional scanning and printing technique: A preliminary, randomized, controlled, open-label study. Prosthet. Orthot. Int. 2018, 42, 636–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlhauser, M.; Vasilyeva, A.; Kamolz, L.-P.; Bürger, H.K.; Schintler, M. Metacarpophalangeal Joint Reconstruction of a Complex Hand Injury with a Vascularized Lateral Femoral Condyle Flap Using an Individualized 3D Printed Model—A Case Report. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Yang, G.; Yu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Li, S.; Zheng, Q.; Zhang, B. Surgical treatment of intra-articular distal radius fractures with the assistance of three-dimensional printing technique. Medicine 2020, 99, e19259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, S.V.; Gupta, S.K.; Holla, N.; Chatterjee, K. Resection of Osteoid Osteoma Using Three-Dimensional (3D) Printing. Indian J. Orthop. 2022, 56, 1657–1661. [Google Scholar]

- Kunz, M.; Ma, B.; Rudan, J.F.; Ellis, R.E.; Pichora, D.R. Image-Guided Distal Radius Osteotomy Using Patient-Specific Instrument Guides. J. Hand Surg. 2013, 38, 1618–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuptniratsaikul, V.; Luangjarmekorn, P.; Charoenlap, C.; Hongsaprabhas, C.; Kitidumrongsook, P. Anatomic 3D-Printed Endoprosthetic with Multiligament Reconstruction After En Bloc Resection in Giant Cell Tumor of Distal Radius. JAAOS Glob. Res. Rev. 2021, 5, e20.00178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.Y.; Lee, S.H.; Leigh, J.H.; Nam, H.S.; Hwang, E.Y.; Lee, J.Y.; Han, S.; Lee, G. Functional improvement by body-powered 3D-printed prosthesis in patients with finger amputation: Two case reports. Medicine 2022, 101, e29182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Liu, Z.; Shi, Q.; Li, T.; Liu, Z.; Yang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Dai, K.; Yu, C.; et al. Varisized 3D-Printed Lunate for Kienböck’s Disease in Different Stages: Preliminary Results. Orthop. Surg. 2020, 12, 792–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A Marcano-Fernández, F.; Berenguer, A.; Fillat-Gomà, F.; Corderch-Navarro, S.; Cámara-Cabrera, J.; Sánchez-Flò, R. A customized percutaneous three-dimensional-printed guide for scaphoid fixation versus a freehand technique: A comparative study. J. Hand Surg. 2021, 46, 1081–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oka, K.; Shigi, A.; Tanaka, H.; Moritomo, H.; Arimitsu, S.; Murase, T. Intra-articular corrective osteotomy for intra-articular malunion of distal radius fracture using three-dimensional surgical computer simulation and patient-matched instrument. J. Orthop. Sci. 2020, 25, 847–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oki, S.; Matsuo, T.; Furuhata, R.; Iwabu, S. Scaphoid non-union with pre-existing screws treated by 3D preoperative planning. BMJ Case Rep. 2021, 14, e239548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osagie, L.; Shaunak, S.; Murtaza, A.; Cerovac, S.; Umarji, S. Advances in 3D Modeling: Preoperative Templating for Revision Wrist Surgery. Hand 2017, 12, NP68–NP72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, W.; Verstreken, F.; Vanhees, M. Correction of scaphoid nonunion humpback deformity using three-dimensional printing technology. J. Hand Surg. 2020, 46, 430–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raeker-Jordan, E.; Martinez, M.; Shimada, K. 3D Printing of Customizable Phantoms to Replace Cadaveric Models in Upper Extremity Surgical Residency Training. Materials 2022, 15, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roner, S.; Carrillo, F.; Vlachopoulos, L.; Schweizer, A.; Nagy, L.; Fuernstahl, P. Improving accuracy of opening-wedge osteotomies of distal radius using a patient-specific ramp-guide technique. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2018, 19, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Rossello, M.I. Short-term findings of a custom-made 3D-printed titanium partial scaphoid prosthesis and scapholunate interosseous ligament reconstruction. BMJ Case Rep. 2021, 14, e241090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samaila, E.M.; Negri, S.; Zardini, A.; Bizzotto, N.; Maluta, T.; Rossignoli, C.; Magnan, B. Value of three-dimensional printing of fractures in orthopaedic trauma surgery. J. Int. Med. Res. 2020, 48, 300060519887299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, M.; Holzbauer, M.; Kwasny, O.; Huemer, G.M.; Froschauer, S. 3D Printing for scaphoid-reconstruction with medial femoral condyle flap. Injury 2020, 51, 2900–2903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, M.; Holzbauer, M.; Froschauer, S.M. Metacarpal reconstruction with a medial femoral condyle flap based on a 3D-printed model: A case report. Case Rep. Plast. Surg. Hand Surg. 2022, 9, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutz, B.M.; Sudbury, D.; Scott, N.; Mayoh, B.; Chan, B. Customized Three-Dimensional Printed Splints for Neonates in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit: Three Case Reports. Am. J. Occup. Ther. Off. Publ. Am. Occup. Ther. Assoc. 2022, 76, 7606205020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweizer, A.; Fürnstahl, P.; Nagy, L. Three-Dimensional Correction of Distal Radius Intra-Articular Malunions Using Patient-Specific Drill Guides. J. Hand Surg. 2013, 38, 2339–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedigh, A.; Kachooei, A.R.; Vaccaro, A.R.; Rivlin, M. Contactless Remote 3D Splinting during COVID-19: Report of Two Patients. J. Hand Surg. Asian Pac. Vol. 2022, 27, 398–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shintani, K.; Kazuki, K.; Yoneda, M.; Uemura, T.; Okada, M.; Takamatsu, K.; Nakamura, H. Computer-Assisted Three-Dimensional Corrective Osteotomy for Malunited Fractures of the Distal Radius Using Prefabricated Bone Graft Substitute. J. Hand Surg. Asian Pac. Vol. 2018, 23, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štefanovič, B.; Michalíková, M.; Bednarčíková, L.; Trebuňová, M.; Živčák, J. Innovative approaches to designing and manufacturing a prosthetic thumb. Prosthet. Orthot. Int. 2020, 45, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Temmesfeld, M.J.; Hauksson, I.T.; Mørch, T. Intra-Articular Osteotomy of the Distal Radius with the Use of Inexpensive In-House 3D Printed Surgical Guides and Arthroscopy. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 2020, 10, e0424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayan, A.; Bhatia, V.; Arora, S.; Gupta, S. Completely digitally fabricated custom functional finger prosthesis. J. Indian Prosthodont. Soc. 2023, 23, 198–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, S.; Li, K.; Cao, P.; Li, J.; Wu, G. Clinical feasibility and application value of computer virtual reduction combined with 3D printing technique in complex acetabular fractures. Exp. Ther. Med. 2019, 17, 3630–3636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Min, L.; Lu, M.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, X.; Tang, F.; Luo, Y.; Duan, H.; et al. The functional outcomes and complications of different reconstruction methods for Giant cell tumor of the distal radius: Comparison of Osteoarticular allograft and three-dimensional-printed prosthesis. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2020, 21, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.-P.; Xu, H.-J.; Liao, W.; Li, Z.-H. Clinical application of instant 3D printed cast versus polymer orthosis in the treatment of colles fracture: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2024, 25, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, M.-M.; Tang, K.-L.; Yuan, C.-S. 3D printing lunate prosthesis for stage IIIc Kienböck’s disease: A case report. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2017, 138, 447–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhang, G.; He, Z.; Zhong, S.; Chen, Y.; Wei, C.; Zheng, Y.; Lin, H.; Li, W.; Huang, W. Anatomical reduction and precise internal fixation of intra-articular fractures of the distal radius with virtual X-ray and 3D printing. Phys. Eng. Sci. Med. 2019, 43, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, H.-W.; Feng, J.-T.; Yu, B.-F.; Shen, Y.-D.; Gu, Y.-D.; Xu, W.-D. 3D printing-assisted percutaneous fixation makes the surgery for scaphoid nonunion more accurate and less invasive. J. Orthop. Transl. 2020, 24, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, C.S.; Tang, Y.; Xie, H.Q.; Liang, T.T.; Li, H.T.; Tang, K.L. Application of 3 dimension-printed injection-molded polyether ether ketone lunate prosthesis in the treatment of stage III Kienböck’s disease: A case report. World J. Clin. Cases 2022, 10, 8761–8767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuang, F.; Hu, W.; Shao, Y.; Li, H.; Zou, H. Treatment of Intercondylar Humeral Fractures With 3D-Printed Osteosynthesis Plates. Medicine 2016, 95, e2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Cheung, T.F.; Fan, V.C.; Sin, K.M.; Wong, C.W.; Leung, G.K.K. Applications of Three-Dimensional Printing in Surgery. Surg. Innov. 2017, 24, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiner, A.J.; Schmidutz, F.; Ateschrang, A.; Ihle, C.; Stöckle, U.; Ochs, B.G.; Gonser, C. Periprosthetic tibial fractures in total knee arthroplasty—An outcome analysis of a challenging and underreported surgical issue. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2018, 19, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria | |

|---|---|---|

| Study design |

|

|

| Population |

|

|

| Intervention |

| |

| Outcome Measures |

| |

| Publication details |

|

| Study | Year | Methodology | Comparative Study | Funding | Country | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anderson et al. [23] | 2021 | Case report | No | No | USA | To investigate the use of a 3D-printed prosthetic hand in enhancing a child’s participation, confidence, and satisfaction in gymnastic classes |

| Belloti et al. [24] | 2021 | Prospective cohort | No | Yes | Brazil | Evaluate the functional and radiographic outcomes of corrective osteotomies for symptomatic distal radius malunions through planning with prototyping in 3D printing |

| Belloti et al. [25] | 2021 | Case series | No | Yes | Brazil | Prototyping based on 3D reconstruction of computed tomography scans showing its use in clinical cases |

| Bizzotto et al. [13] | 2015 | Prospective cohort | No | No | Italy | Surgeons’ appreciation of articular fragments dislocation, preoperative planning for placement fixation and patient/resident/student education |

| Bizzotto et al. [3] | 2016 | Technical note | No | Yes | Italy | Preoperative planning for placement of fixation and patient education |

| Brichacek et al. [26] | 2018 | Prospective cohort | No | No | Canada | Surgical education for K-wire placement in common hand fractures |

| Casari et al. [27] | 2021 | Prospective case series | Yes | Yes | Switzerland | Evaluate feasibility of computer-assisted surgical planning and 3D-printed patient-specific instrumentation for treatment of distal intraarticular radius fractures |

| Chen et al. [11] | 2018 | Case report | No | Yes | China | Report the use of a 3D-printed porous tantalum prosthesis in the limb-salvage surgery of a patient with distal radial osteosarcoma |

| Chen et al. [28] | 2017 | Randomized controlled trial | Yes | Yes | China | Evaluate the feasibility, accuracy, and effectiveness of applying 3D printing technology for preoperative planning for die-punch fractures |

| Chen et al. [29] | 2021 | Clinical trial | No | Yes | Hong Kong | Use 3D-printed casts, developed for distal radius fracture treatment, to provide the foundation for conducting additional clinical trials, and to perform clinical assessments |

| Chen et al. [7] | 2019 | Randomized controlled trial | Yes | Yes | China | Evaluate the use of 3D printing models for preoperative planning in cases of complex fracture |

| Copeland et al. [30] | 2022 | Case report | No | Yes | USA | Compare the functional outcomes and patient satisfaction of a standard clinic-fitted transradial prosthesis versus a remotely fitted 3D-printed prosthesis |

| El Khoury et al. [31] | 2022 | Randomized controlled trial | Yes | Yes | Belgium | Compare the effectiveness of 3D-printed splints with conventional removable splints in managing distal radius fractures |

| Exner et al. [32] | 2021 | Case report | No | No | Switzerland | Demonstrate the use of 3D printing technology to create a patient-specific mold for forming an antibiotic-loaded cement spacer in the treatment of an infected sarcomatous radius |

| Eyiis et al. [33] | 2023 | Randomized controlled crossover trial | Yes | No | Netherlands | Compare the effectiveness, patient satisfaction, and compliance of a 3D-printed customized brace versus a conventional plaster brace for the non-operative management of trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis |

| Grincuk et al. [34] | 2023 | Prospective randomized control study | Yes | No | Lithuania | Evaluate whether the use of 3D-printed models for preoperative planning improves short-term functional outcomes and reduces complication rates in the surgical treatment of distal radius fractures |

| Guebeli et al. [35] | 2024 | Randomized controlled trial | Yes | Yes | Netherlands | Compare clinical outcomes between 3D-printed splints made of photopolymer resin and traditional fiberglass casts for the treatment of distal radial fractures |

| Honigmann et al. [36] | 2016 | Case report | No | No | Switzerland | Describe a technique using a 3D-printed drill guide and template to simplify the surgical reconstruction of a malunited distal radius fracture |

| Houdek et al. [37] | 2016 | Case report | No | No | USA | Describe a novel technique for preoperative surgical planning for an osteoarticular medial femoral condyle graft to replace the proximal pole of a scaphoid |

| Huang et al. [38] | 2021 | Case series | No | Yes | Taiwan | Demonstrate the effectiveness of a 3D-printed orthosis for improving the range of motion in patients with wrist and thumb contractures. Describe and demonstrate a newly designed device to ease splint construction, a 3D-printed “shark fin”-shaped device that works as a static progressive orthosis for hand rehabilitation |

| Inge et al. [19] | 2018 | Case report | No | No | Netherlands | 3D virtual surgical planning for osteotomy and saw guides for osteotomy and iliac crest bone graft |

| Jew et al. [39] | 2019 | Case series | No | No | USA | Improve preoperative planning for a series of complex scaphoid fractures, particularly with implant choice and positioning |

| Joo et al. [40] | 2021 | Case report | No | Yes | South Korea | Evaluate the effectiveness of a 3D-printed exoskeleton robot in restoring hand function for a patient with hand dysfunction following burn injuries |

| Kim et al. [41] | 2018 | Randomized controlled trial | Yes | Yes | South Korea | Develop a personalized wrist orthosis using a 3D scanner/printer for patients with wrist pain |

| Kohlhauser et al. [42] | 2023 | Case report | No | No | Austria | Demonstrate the successful surgical management of a complex hand trauma using individualized 3D printing technology for joint reconstruction |

| Kong et al. [43] | 2020 | Randomized controlled trial | Yes | Yes | China | Evaluate the effectiveness and safety of surgical treatment of intra-articular distal radius fractures with the assistance of 3D printing technique |

| Krishnal et al. [44] | 2022 | Case report | No | No | India | Demonstrate the use of 3D printing technology in creating bone models and surgical guides for minimally invasive resection of osteoid osteoma in the distal radius without intraoperative imaging |

| Kunz et al. [45] | 2013 | Case series | No | Yes | Canada | Present a method in which patient-specific instrument guides are used to navigate the alignment of the distal and proximal fragments with respect to a preoperative plan and to assist with plate fixation to achieve planned realignment |

| Kuptniratsaikul et al. [46] | 2021 | Case report | No | Yes | Thailand | Presentation of a reconstruction technique using a custom 3D-printed endoprosthesis with multiple ligament reconstruction for anatomical restoration of a large defect |

| Lee et al. [47] | 2022 | Case series | No | Yes | South Korea | Demonstrate the use of body-powered 3D-printed finger prostheses, highlighting their potential as a functional and cost-effective alternative |

| Ma et al. [48] | 2020 | Retrospective case series | No | Yes | China | Evaluate the feasibility of arthroplasty with varisized 3D printing lunate prosthesis for the treatment of advanced Kienböck’s disease |

| Marcano-Fernandez et al. [49] | 2021 | Prospective cohort | Yes | No | Spain | Compare the accuracy and reliability of percutaneous fixation of minimally displaced scaphoid fractures using a custom 3D-printed guide with a conventional freehand method |

| Matter-Parrat and Liverneaux [5] | 2019 | Case report | No | No | France | Provide how 3D printed objects can be used in radial osteotomy and its application on a clinical case |

| Oka et al. [50] | 2020 | Retrospective case series | No | Yes | Japan | Investigate five patients with malunited intra-articular distal radius fracture who underwent corrective osteotomy performed using a patient-matched instrument designed/manufactured based on preoperative 3D computer simulation |

| Oki et al. [51] | 2021 | Case report | No | Yes | Japan | Demonstrate the use of a 3D-printed model volar plate for preoperative planning in a case of scaphoid fracture non-union |

| Osagie et al. [52] | 2017 | Case series | No | No | UK | Use of 3D printing in operative planning of wrist surgery revision |

| Peeters et al. [53] | 2021 | Letter to the editor | No | No | Belgium | Use of 3D printing technology to aid in the reconstruction of scaphoid non-union humpback deformities |

| Raeker-Jordan et al. [54] | 2022 | Case report | No | No | USA | Develop and validate novel, high-fidelity 3D-printed surgical training phantoms for distal radius fracture reductions as an alternative to traditional cadaveric models |

| Roner et al. [55] | 2018 | Retrospective cohort | Yes | Yes | Switzerland | Compare the accuracy of navigation of 3D planned opening-wedge osteotomies using a ramp-guide over guide techniques relying solely on pre-drilled holes |

| Rossello [56] | 2021 | Case report | No | No | Italy | Evaluate the use of a custom-made 3D-printed titanium implant for scaphoid replacement and scapholunate ligament reconstruction in a patient with non-union and necrosis. |

| Samaila et al. [57] | 2020 | Prospective cohort | No | None | Italy | Education of patients during informed consent and models used as templates for open reduction internal fixation planification |

| Schmidt et al. [58] | 2020 | Case report | No | No | Austria | Demonstrate the use of 3D printing-assisted medial femoral condyle flap for metacarpal reconstruction following the resection of a large giant cell tumor recurrence |

| Schmidt et al. [59] | 2022 | Case series | No | None | Austria | 3D virtual surgical planning for resection of proximal pole of scaphoid and intraoperative verification of medial femoral condyle flap to be harvested |

| Schutz et al. [60] | 2022 | Case series | No | No | USA | To assess the feasibility of utilizing 3D scanning, design, and printing technologies for creating customized splints for neonates |

| Schweizer et al. [61] | 2013 | Case series | No | NR | Switzerland | Analyze the feasibility of combining computer-assisted 3D planning with patient-specific drill guides and evaluate this technology’s surgical outcomes for distal radius intra-articular malunions |

| Sedigh et al. [62] | 2022 | Case series | No | No | USA | To explore the use of 3D-printed splints generated from calibrated 2D images, offering a contactless alternative to conventional splinting |

| Shintani et al. [63] | 2018 | Prospective cohort | No | NR | Japan | Investigate the results of a computer-assisted, 3D corrective osteotomy using prefabricated bone graft substitute to treat distal radius malunited fractures |

| Stefanovicet al. [64] | 2021 | Case report | No | No | Slovakia | Demonstrate the design and fabrication of an individual passive thumb prosthesis using 3D scanning and printing |

| Temmesfeld et al. [65] | 2020 | Case report | No | NR | Norward | Design and produce patient-specific surgical guides in-house with a benchtop 3D printer to perform an arthroscopy-assisted intra-articular osteotomy |

| Vijayan et al. [66] | 2023 | Case report | No | No | India | Demonstrate the use of 3D printing to create a functional prosthesis for an amputated index finger, aiming to improve functionality, efficiency, and psychological well-being |

| Wan et al. [67] | 2019 | Case series | No | Yes | China | Explore the feasibility of employing computer-aided design and 3D-printed personalized guide plate for the mini-invasive percutaneous internal screw fixation of fractured scaphoid |

| Wang et al. [68] | 2020 | Retrospective cohort | Yes | Yes | China | Compare the outcomes of an osteoarticular allograft versus a custom-made prosthesis reconstruction |

| Xiao et al. [69] | 2024 | Randomized controlled trial | Yes | Yes | China | To compare the short-term effectiveness, safety, and advantages of 3D-printed wrist casts versus polymer orthoses in the treatment of Colles fractures. |

| Xie et al. [70] | 2018 | Case report | No | Yes | China | Test the lunate prosthesis intraoperatively to stage IIIc Kienböck’s disease |

| Xu et al. [71] | 2019 | Prospective cohort | No | Yes | China | To evaluate and precisely internal fix intra-articular distal radial fracture using virtual X-ray and 3D printing technologies |

| Yin et al. [72] | 2020 | Prospective cohort | Yes | Yes | China | Determine whether a 3D-printed guiding plate system could facilitate the modified procedure for arthroscopic treatment of nondisplaced scaphoid non-union |

| Yuan et al. [73] | 2022 | Case report | No | Yes | China | To evaluate the clinical efficacy of a 3D-printed lunate prosthesis in the treatment of stage III Kienböck’s disease |

| N | |

|---|---|

| Patients | 493 (65.6%) |

| Controls | 258 (34.6%) |

| Age (years) | 38 (SD: 14) |

| Time from injury (days) | 356 [IQR: 60–652] |

| Sex * | |

| M | 302 (50.2%) |

| F | 300 (49.8%) |

| Anatomic Area of Interest | |

| Distal radius | 34 (51.5%) |

| Metacarpals | 6 (9.1%) |

| Phalanges | 5 (7.6%) |

| Scaphoid | 10 (15.2%) |

| Lunate | 3 (4.5%) |

| Carpus | 1 (1.5%) |

| Ulnar styloid | 1 (1.5%) |

| Wrist | 2 (3.0%) |

| Trapeziometacarpal joint | 1 (1.5%) |

| Entire hand | 3 (4.5%) |

| Diagnosis | |

| Distal radius fracture | 20 (30.7%) |

| Bennett’s fracture | 1 (1.5%) |

| Metacarpal facture | 3 (4.6%) |

| Phalanx fracture | 2 (3.1%) |

| Distal radius malunion/non-union | 7 (10.8%) |

| Scaphoid avascular necrosis/malunion/non-union | 8 (12.3%) |

| Kienböck | 3 (4.6%) |

| Ulnar malunion/non-union | 1 (1.5%) |

| Degenerative wrist | 2 (3.1%) |

| Tumor | 6 (9.2%) |

| Scaphoid fracture | 2 (3.1%) |

| Skeletal dysplasia | 1 (1.5%) |

| Chromosomal abnormalities | 1 (1.5%) |

| Congenital hand deficiency | 1 (1.5%) |

| Trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis | 1 (1.5%) |

| Proximal interphalangeal joint amputation | 2 (3.1%) |

| Transradial amputation | 1 (1.5%) |

| Burn | 1 (1.5%) |

| Congenital absence of the thumb | 1 (1.5%) |

| FPL rupture | 1 (1.5%) |

| Study | Printer Used | Type of Material | Manufacture Time | Price per Surgery | Printer Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anderson et al. [23] | Lulzbot TAZ 6 | Polylactic Acid (PLA) | <2 days (printing, assembling) | USD 25 | NR |

| Belloti et al. [24] | NR | Polylactic acid | NR | NR | NR |

| Belloti et al. [25] | 3D printer (Makerbot, São Paulo, Brazil) | Polylactic acid | NR | NR | NR |

| Bizzotto et al. [13] | Pro-Jet 660 Color | Gypsum-dust material | 4 h | USD 10/model | NR |

| Bizzotto et al. [3] | Stratasys uPrint SE (Stratasys Ltd. 7665 Commerce Way, Eden Prairie, MN 55344, USA) | Acrylonitrile butadiene styrene material | 3–4 h | NR | NR |

| Brichacek et al. [26] | NR | Polyurethane foam with iron powder | NR | USD 50 | NR |

| Casari et al. [27] | NR | NR | NR | USD 220–320/case | NR |

| Chen et al. [11] | 3D printer (3D ORTHO; Waston Med Inc., Changzhou, Jiangsu, China) | NR | 5 h (1 h pre-processing, 3–4 h printing) | NR | NR |

| Chen et al. [28] | Selective laser sintering (SLS) EOS P395 or Stereolithography (SLA) printer RS4500 (UnionTech, China) | Polypropylene (PP) and polyamide (PA2200) | NR | USD 150/cast | NR |

| Chen et al. [29] | UP BOX+ 3D printer | Polylactic Acid (PLA) | NR | NR | NR |

| Chen et al. [7] | 3D printer (3D ORTHO; Waston Med Inc., Changzhou, Jiangsu, China) | Polylactic acid | ~5 h (1 h pre-processing, 3–4 h printing) | NR | NR |

| Copeland et al. [30] | Ultimaker 2 Extended | Polylactic acid (PLA) | 2 days (construction) 8–10 h (printing) | NR | NR |

| El Khoury et al. [31] | NR | Polyolefin materials (mixture of additive and polypropylene) | 15 h | NR | NR |

| Exner et al. [32] | EOS Formiga | Polyamid | 8 h (preoperative planning and guide design) 3 workdays to receive the printed molds | USD 2500 (planning and guide design) USD 600 (manufacturing) | NR |

| Eyiis et al. [33] | NR | NR | NR | EUR 590 | NR |

| Grincuk et al. [34] | Zortrax M200Plus | Polylactic Acid (PLA) | NR | NR | NR |

| Guebeli et al. [35] | Atum 3D DLP Station | Photopolymer resin | 145 min (scanning, modeling, printing, post-processing, and application) | USD 20/EUR 17.50 | USD 30,000 |

| Honigmann et al. [36] | Stratasys (Objet Eden 250) | Biocompatible UV curable acrylate (Med-610, Stratasys) | NR | NR | NR |

| Houdek et al. [37] | Polyjet 3D printer | Proprietary polymer | NR | NR | NR |

| Huang et al. [38] | UP Box 3D printer, Go Hot Technologies Co., Ltd., Taiwan | Polylactic Acid (PLA) | 7 h | USD 4/model | NR |

| Inge et al. [19] | Ultimaker 3 | NR | 1 h | EUR 10/saw guide | EUR 3626 |

| Jew et al. [39] | Dimension Elite 3-dimensional printer (Stratasys) | Acrylonitrile butadiene styrene | NR | NR | NR |

| Joo et al. [40] | FlashForge Creator Pro | Polylactic Acid (PLA) | < 2 h | USD 30 | NR |

| Kim et al. [41] | FINEBOT Z420 | Thermoplastic polyurethane | 6 h | USD 70 USD/splint | NR |

| Kohlhauser et al. [42] | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Kong et al. [43] | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Krishnal et al. [44] | Ultimaker S5 Bundle | Polylactic Acid (PLA) | NR | NR | NR |

| Kunz et al. [45] | Stratasys, Dimension SST | Thermoplastic acrylonitrile butadiene styrene | NR | NR | NR |

| Kuptniratsaikul et al. [46] | Mlab 200R | Titanium (Ti-6AI-4V grade) | NR | NR | NR |

| Lee et al. [47] | Fused filament fabrication type 3D printer | Acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS) and thermoplastic polyurethane resin | 1 day (measurement to prosthesis production) | USD 30 | NR |

| Ma et al. [48] | NR | Photosensitive resin for model and titanium alloy (Ti-6Al-4V) for prosthesis | NR | NR | NR |

| Marcano-Fernandez et al. [49] | FORMIGA P 110 Velocis (EOS GmbH- Electro Optical Systems, Munich, Germany) | Polyamide, PA2200 | 6–8 h | EUR 330/guide | NR |

| Matter-Parrat and Liverneaux [5] | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Oka et al. [50] | Formiga P, EOS GmbH Electro Systems, Krailling, Germany or Eden250, Objet Geometries, Rehovot, Israel | Medical-grade resin | NR | USD 1500–2000 USD/model | NR |

| Oki et al. [51] | Uprint SE Plus | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Osagie et al. [52] | NR | Polyethylene | 144 h | GBP ~34/model | NA |

| Peeters et al. [53] | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Raeker-Jordan et al. [54] | Raise3D Pro2 printer series, FormLabs Form3 resin printer | Holden’s HX-80 latex, FormLabs resin | > 60 h (printing: 20 h, preparation: 10–15 h, curing and cooling: 30 h) | USD 80 | NR |

| Roner et al. [55] | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Rossello [56] | NR | Titanium | NR | NR | NR |

| Samaila et al. [57] | 3D printer (HP Design Jet 3D, Hewlett-Packard, Palo Alto, CA, USA) | Acrylonitrile butadiene styrene | 4 h | EUR 50 | NR |

| Schmidt et al. [58] | Formlabs (form 2 printer) | Clear photopolymer resin | NR | NR | NR |

| Schmidt et al. [59] | Formlabs 2 printer | Clear photopolymer resin | NR | NR | NR |

| Schutz et al. [60] | Fusion3 F410 | Acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS) | 1.5 h (design) 25 min (printing) | USD 0.50/splint | NR |

| Schweizer et al. [61] | Materialise and Medacta (Castel San Pietro, Switzerland) | Polyamide (PA-12) | 2–4 h | USD 220–320/case | NR |

| Sedigh et al. [62] | NR | Polylactic Acid (PLA) | NR | USD 300–900 | NR |

| Shintani et al. [63] | Z Printer 650®; 3D Systems Inc., Valencia, CA, USA | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Stefanovicet al. [64] | MakerBot Replicator1 Fused filament fabrication (FFF) 3D printer, Bq Witbox FFF 3D printer, | Polylactic Acid (PLA), Arnitel Eco | NR | NR | NR |

| Temmesfeld et al. [65] | M200 benchtop 3D printer (Zortrax) | 1.75 mm proprietary ultra-filament | NR | USD 30–40/model | NR |

| Vijayan et al. [66] | Digital Light Processing 3D Printer | Photopolymer resin | NR | NR | NR |

| Wan et al. [67] | NR | MED610 biocompatible resin | 12.5 h | USD ~420/design | NR |

| Wang et al. [68] | Electron beam melting technology (ARCAM Q10, Mölndal, Sweden) | Ultrahigh-molecular-weight polyethylene | 2–4 w | NR | NR |

| Xiao et al. [69] | BY-3D-I instant 3D external fixation printer | Polyester fiber polymer material | 25 min | NR | NR |

| Xie et al. [70] | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Xu et al. [71] | Zortrax M200 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Yin et al. [72] | Stratasys Objet30 prime | Photopolymer of medical compatibility | 30 h | USD 300/3D guiding plate | NR |

| Yuan et al. [73] | NR | Polyether ether ketone | NR | NR | NR |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dababneh, S.; Dababneh, N.; El Sewify, O.; Legler, J.; Ma, X.; Chan, C.M.; Danino, A.; Efanov, J.I. Three-Dimensional Printing in Hand Surgery: What Is New? A Systematic Review. J. Pers. Med. 2025, 15, 611. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15120611

Dababneh S, Dababneh N, El Sewify O, Legler J, Ma X, Chan CM, Danino A, Efanov JI. Three-Dimensional Printing in Hand Surgery: What Is New? A Systematic Review. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2025; 15(12):611. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15120611

Chicago/Turabian StyleDababneh, Said, Nadine Dababneh, Omar El Sewify, Jack Legler, Xiya Ma, Chung Ming Chan, Alain Danino, and Johnny I. Efanov. 2025. "Three-Dimensional Printing in Hand Surgery: What Is New? A Systematic Review" Journal of Personalized Medicine 15, no. 12: 611. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15120611

APA StyleDababneh, S., Dababneh, N., El Sewify, O., Legler, J., Ma, X., Chan, C. M., Danino, A., & Efanov, J. I. (2025). Three-Dimensional Printing in Hand Surgery: What Is New? A Systematic Review. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 15(12), 611. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15120611