1. Introduction

Numerous traits have been effectively linked to specific areas of the genome by genome-wide association studies (GWAS) [

1]. The process by which variations impact the phenotype that they are linked to is still unclear for many of these observations [

2]. The majority of trait-associated variations found by GWAS are thought to function by changing gene expression rather than changing the protein coding, and are found in regulatory areas of the genome [

3]. This hypothesis is supported by the discovery of overlaps between GWAS risk variants and genomic loci influencing markers of genome regulation (like histone modifications) and enrichment of expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs) at identified GWAS risk loci [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Therefore, combining GWAS with gene expression data is one plausible way to improve knowledge of the processes related to GWAS findings.

DNA methylation is a key process in gene regulation. As such, it is an essential intermediary molecular trait that connects genes to other macro-level phenotypes and may contribute to missing heritability [

8]. Despite their physiological importance, the genetic drivers of DNA methylation patterns remain poorly understood. There is evidence that genetic variation at certain loci correlates with the quantitative characteristic of DNA methylation [

9,

10,

11,

12]. Additionally, previous studies discovered that genetic variants at CpG sites (meSNPs) can possibly disrupt the substrate of methylation reactions and thus, severely alter the methylation status at a single CpG site [

13,

14].

While methylation-associated single-nucleotide polymorphisms (meSNPs) have been identified in various studies, it remains unclear if meSNPs constitute a major class of methylation quantitative trait loci (meQTLs), or if they significantly influence the methylation status of nearby CpG sites [

15,

16,

17,

18]. Most meQTL studies to date have been limited by relatively small sample sizes and the use of low-resolution methylation microarrays, in which meSNPs are sparsely represented. Furthermore, many current meQTL analyses deliberately exclude probes overlapping with sequence variants to avoid confounding due to disrupted probe hybridization [

15,

16].

Pharmacoepigenetics explores the complex relationship between epigenetic modifications and pharmacological responses, emphasizing how drugs can both alter and be affected by epigenetic mechanisms [

19,

20]. Gaining insight into these epigenetic changes is essential in pharmacology, as it could help optimize drug efficacy, reduce adverse reactions, and drive forward the progress of personalized medicine. As a multidisciplinary and continuously evolving field, pharmacoepigenetics merges pharmacology, epigenetics, and other life sciences to shape innovative therapeutic strategies and uncover new drug targets [

21]. Alongside pharmacogenomics—a pharmacological sub-discipline focused on genetic variability in drug response—Pharmacoepigenomics has emerged as a key area of interest. It concentrates on epigenetic therapy, the impact of epigenetic regulation on pharmacokinetics, and its implications in adverse drug reactions [

22].

Finally, both pharmacoepigenetics and pharmacogenomics play a vital role in advancing personalized medicine by shedding light on the intricate relationships between genes, epigenetic mechanisms, and drug responses [

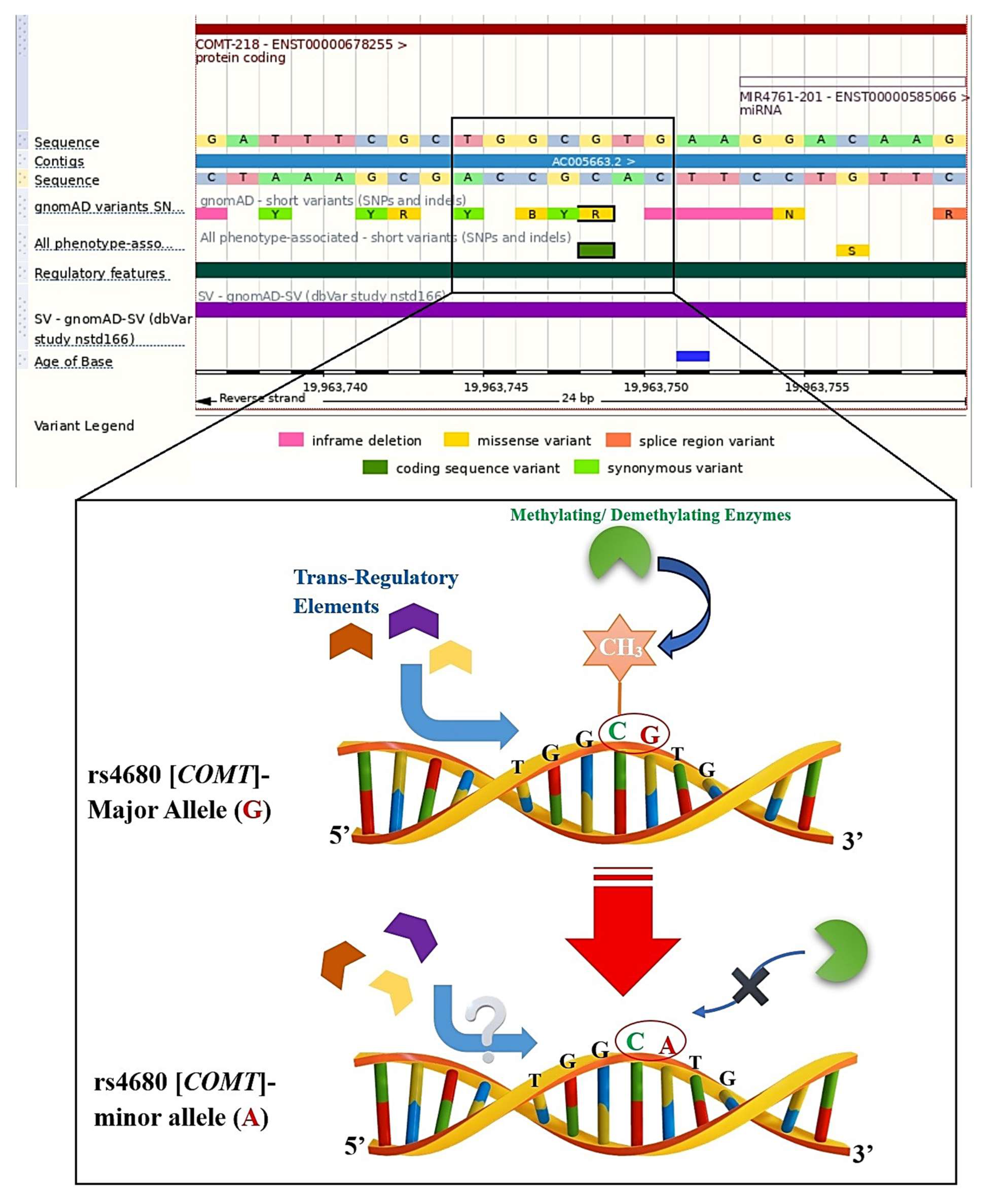

22]. Here, we introduce an innovative idea to test the Genomic-Epigenomic-Phenomic-Pharmacogenomics (G-E-Ph-PGx) axis by employing CpG-PGx SNPs (whose PGx roles are known) and possible CpG-PGx SNPs.

2. Materials and Methods

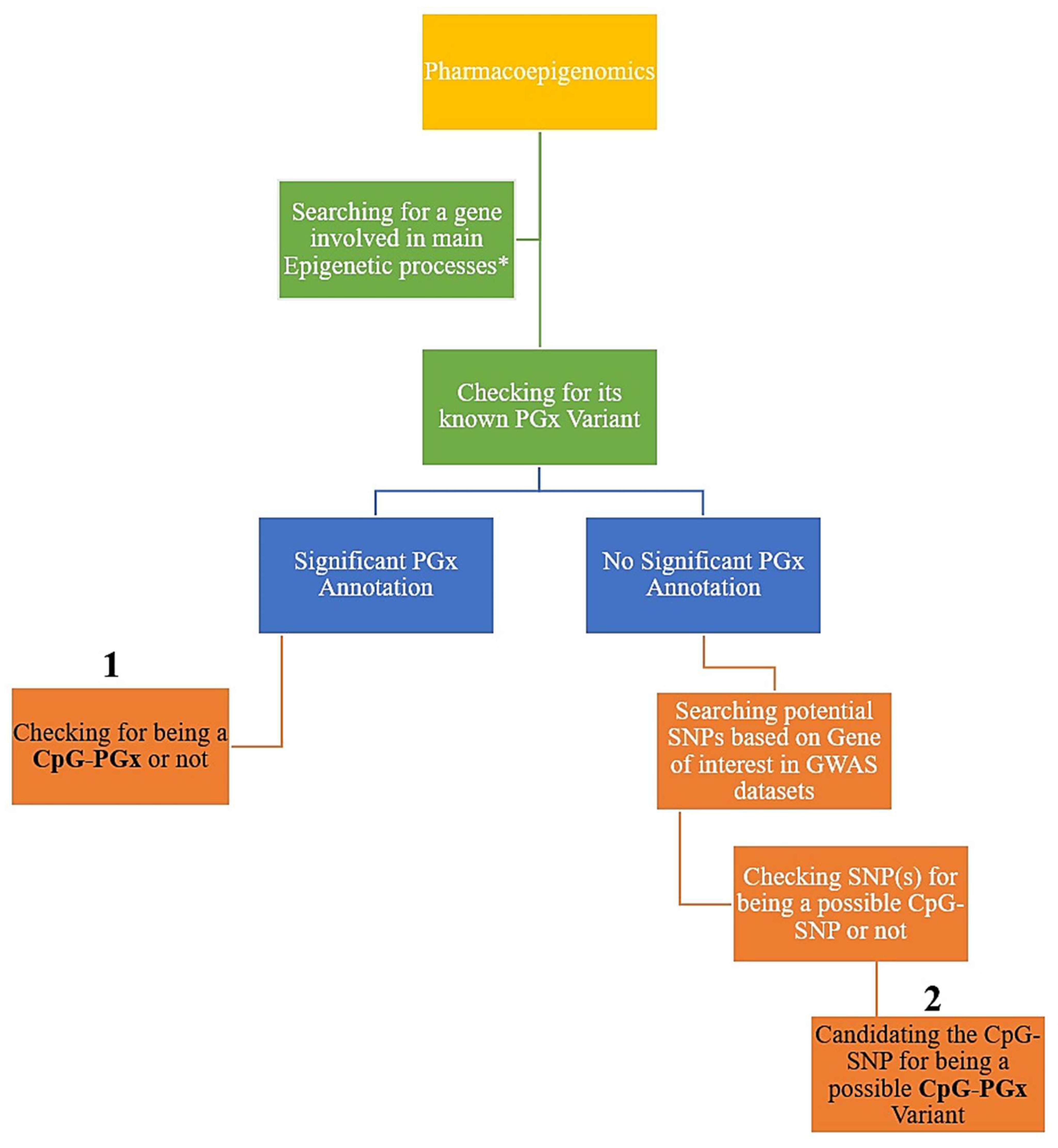

2.1. General Design

Firstly, we analyzed the four major processes in epigenetics, including methylation, demethylation, acetylation, and deacetylation. Then, we searched for the best-scored genes in each epigenetic process according to the relevance score of GeneCards (access date: 1 July 2025,

https://www.genecards.org/) [

23]. Accordingly, we calculated the 1st–25th best-scored genes for each of the 4 epigenetic processes. Secondly, we checked every 100 top genes in PharmGKB (access date: 1 July 2025, now ClinPGx available at:

https://www.clinpgx.org/) [

24] to see if they had at least one significant PGx annotation. Thirdly, each PGx variant was subsequently checked for possible categorization as a CpG-PGx SNP. To accomplish this, we employed the Ensembl genome browser with reference genome GRCh38; more specifically, we manually searched the rsID for each SNP in Ensembl (Ensembl 114 corresponding release of Ensembl Genomes 61). We also checked the major allele, a nucleotide pre-and post to determine its location relevant to a CpG dinucleotide. Following this event, we checked the minor allele accordingly. If the major allele was in a CpG dinucleotide, then it would be a CpG-SNP, which could be disrupted by a minor allele, and if the major allele shaped a new CpG-SNP, then it could be considered as a forming CpG site. Ensembl was also utilized to determine SNP functions, including exonic (missense or synonymous), intronic (regulatory), upstream (5′UTR), and downstream (3′UTR). It is indeed noteworthy that the classification of regions linking SNPs was directly obtained from Ensembl (access date: 1 July 2025,

https://www.ensembl.org/index.html), such as Epigenetically Modifiable Accessible Region (EMAR), Promoter, Enhancers, and CTCF Binding Sites (CBS). Thus, these regions were automatically displayed by zooming the sequential viewer. To determine any newly found CpG-PGx SNP based on our hypothesis-generating approach, we investigated genes that had no significant PGx annotation in the GWAS catalog (access date: 1 July 2025,

https://www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas/home) [

25]. Finally, we checked the potential SNPs (based on the best

p-values) for possible categorization as a CpG SNP. These CpG SNPs were designated in the

Section 3 as new CpG-PGx SNPs. The whole process adhered to a hierarchal flow which provided any potential role SNPS of PGx annotations in both epigenetic processes or as a pharmacoepigenetic factor (

Figure 1).

Applying GeneCards, we included 100 best-scored genes based on 4 epigenetic processes, including methylation, demethylation, acetylation, and deacetylation (25 top genes of each one). It is noteworthy that all of the included genes were protein-coding due to the major interactions of protein–drugs in real-world findings. As such, this provided high confidence in our introduction of new CpG-PGx SNP(s) for future confirmations. As a well-known dataset, we established our strategy utilizing PharmGKB information regarding its basis, consisting of CPIC and DPWG as its main pillars. Finally, to further confirm the new CpG-PGx SNPs, we utilized the GWAS catalog for a gene of interest and refined the potential SNPs based on its classified data.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

According to our analysis strategy, we prioritized and filtered genes, PGx annotations, and CpG-SNPs related to various statistical scores. Firstly, we utilized GeneCards data for determining the top genes in 4 epigenetic processes (methylation, demethylation, acetylation, and deacetylation) based on Elasticsearch 7.11, including the Relevance score. The theory behind Relevance Scoring is that Lucene (and thus Elasticsearch) utilizes the Boolean model to find matching documents, and a formula termed “the practical scoring function” to compute relevance. This formula, itself, borrows concepts from the term frequency/inverse document frequency and the vector space model; however, it adds more-modern characteristics such as a field length normalization, coordination factor, and term/query clause boosting. Importantly, supplementary boosting is provided for the annotations, including the Symbol, Aliases, and Descriptions, Accessions for the major bioinformatics databases (NCBI, Ensembl, SwissProt), Molecular function(s), Gene Summaries, Variants with Clinical Significance, and Elite disorders. Additionally, we also employed PharmGKB, which is a pharmacogenomics resource that incorporates clinical data, including clinical guidelines and medication labels, associations of potentially clinically actionable gene-drug, and genotype-phenotype linkages. To note, PharmGKB collects, curates, and publicizes knowledge regarding the effect of human genetic variation on drug responses. This is accomplished via several activities such as annotating the genetic variants and gene–drug–disease relationships via literature review: summarizing the vital pharmacogenomic genes, associations between genetic variants and drugs, and drug pathways, and curating FDA drug labels covering pharmacogenomic data. The main filtering step in PharmGKB actually considered a significant p-value of lower than 0.05 for all obtained PGx annotations. Finally, we mined a number of genes generating the primary list (remained/extracted from step 1) in the GWAS catalog, and also adjusted the False Discovery Rate (FDR). Moreover, we considered the critical threshold of p-value < 5 × 10−8. Thus, we included the most significant GWAS-based SNPs in the current study to increase the validation of our predictions and narrow the possibilities to be close to future real-world findings.

4. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first hypothesis-generating approach introducing CpG-PGx SNP as a multi-dimensional candidate in a Genomic-Epigenomic-Phenomic-Pharmacogenomics (GEPh-PGx) axis. GEPh-PGx suggests a complicated network of regulatory-functional interactions initiated from the smallest genetic block (SNP) to the broader cellular and molecular interplay leading to known and unknown phenotypes, which, in turn, are linked to pharmacological interactions and treatments. Briefly, GEPh-PGx represents a new aspect of personalized medicine based on the disruption or formation of a CpG site by allele changes in an SNP. This phenomenon clearly helps explain the trans-regulation processes in which these CpG sites can present or remove the possible epigenetic tags for Methylation/Demethylation reactions.

We designed a logical and comprehensive strategy of analysis based on the well-known and documented list of various genes in all four classical epigenetic processes, including methylation, demethylation, acetylation, and deacetylation. In the current investigation, we mined the CpG sites for all these genes involved in methylation/demethylation and also included genes for acetylation and deacetylation processes. Therefore, we selected 100 genes and, following the removal of the duplications (some genes were present in more than one epigenetic process, like TP53), 91 unique genes remained. We followed two pathways, including searching for and introducing potential CpG-PGx SNPs and possible CpG-SNPs to be newly confirmed CpG-PGx SNPs. We found 3 major genes for having the highest number of potential CpG-PGx SNPs, including CYP2B6, CYP2C19, and CYP2D6. Among them, CYP2D6 was found to be the heart of Pharmacoepigenomics. Finally, after a deep search based on GWAS data, we found TET2 as the top-scored candidate for future PGx confirmations according to its number of possible CpG-SNPs.

There are some studies concerning CpG-SNP(s) directly in their titles (26 papers in PubMed) and also in their abstracts (20 papers in PubMed). All the PubMed-indexed papers for CpG-SNPs in their titles can be divided into three main categories, including Neuropsychological disorders, such as suicidal behavior in subjects with schizophrenia [

28], psychosis [

29] and major depressive disorder [

30], metabolic disorders, including type 2 diabetes [

31,

32] and obesity [

33,

34], and cancer biology [

35].

Pharmacoepigenetics and Pharmacoepigenomics revealed a better resulting outcome compared with CpG-SNPs in the literature. We found 24 papers in PubMed with the pharmacoepigenetics or Pharmacoepigenomics linked in their titles. Interestingly, similar to the aforementioned 3 major categories, these papers focused on the same categories. Montagna was one of the first scientists who discussed the epigenetic and pharmacoepigenetic processes in primary headaches and pain [

36]. Leach et al. reviewed pharmacoepigenetics in heart failure and cardiovascular disease (CVD) and concluded that, because epigenetics has a vital role in shaping phenotypic variation in health and disease, understanding and manipulating the epigenome has a massive capacity for the treatment and prevention of common human diseases [

37]. In the context of cancer, Candelaria et al., with an emphasis on gemcitabine, reviewed an update of genetic and epigenetic bases that might account for inter-individual variations in therapeutic results [

38]. Accordingly, Nasr et al. studied pharmacoepigenetics in breast cancer [

39], Fornaro et al. reviewed pharmacoepigenetics in gastrointestinal cancer [

40], and Gutierrez-Camino et al. reported on pharmacoepigenetics in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia [

41]. In a meta-analysis, Chu and Yang systematically studied the population diversity impact of DNA methylation on the treatment response and drug ADME in various tissues and cancer types. They concluded that ethnicity should be cautiously considered for future pharmacoepigenetics explorations [

42]. Notably, Nuotio et al. performed a genome-wide methylation analysis of responsiveness to four classes of antihypertensive drugs in the pharmacoepigenetics of hypertension [

43].

The last and most important topic in pharmacoepigenetics is psychological and behavioral phenotypes, such as generalized anxiety disorder [

44], Alzheimer’s disease [

45], and depression [

46], and opioid addiction [

47].

Epigenetic variants have been found near genes and gene regulators, which control the metabolism of drugs, suggesting a role for epigenetic mechanisms in modulating pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics [

48,

49,

50]. Pharmacoepigenetics is a field that studies how epigenetic variability impacts variability in drug response [

20]. Of note, Smith et al.’s idea is completely consistent with our standpoint. They stated that first, we can detect variation in epigenetic markers, second, we can choose key epigenetic biomarker(s) in regions of variance, and third, we can map these biomarker(s) to a drug response phenotype [

20]. Smith et al.’s idea clearly agrees with our initial idea of a GEPh-PGx axis.

Since we found that the

TET2 gene was top, it is important to point out that it is a key player in epigenetics, hematopoiesis, and cancer biology. Its full name is Tet methylcytosine dioxygenase two, located on chromosome 4q24. TET2 is part of the TET family of enzymes, which convert 5-methylcytosine (5mC) to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC), playing a role in DNA demethylation and epigenetic regulation. Specifically, TET2 is involved in the regulation of gene expression, stem cell differentiation, especially in hematopoiesis (formation of blood cells), immune system regulation, and epigenetic reprogramming during development. Interestingly, mutations in

TET2 are somatic (acquired) and commonly found in (1) myeloid malignancies such as myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), acute myeloid leukemia (AML), chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML); myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs); and (2) lymphoid cancers such as Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL) and Peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL). It is also known that

TET2 mutations are among the most common in Clonal Hematopoiesis of Indeterminate Potential (CHIP), a condition where aging individuals develop hematopoietic clones without having full-blown cancer, but with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease and leukemia. Clinically,

TET2 mutations may signal different outcomes depending on the context of the disease.

TET2-mutant cancers may respond differently to hypomethylating agents (like azacitidine or decitabine). Vitamin C (ascorbate) has been studied to enhance

TET activity and DNA demethylation in TET2-deficient cells (preclinical).

TET2 mutations often co-occur with others (e.g.,

ASXL1,

DNMT3A,

IDH2), affecting disease progression and treatment [

51,

52].

Limitations

The current study faces some limitations, which should be considered in similar future investigations. First of all, we used GeneCards data, which may receive updates based on novel findings in the literature. The other limitation may rely on the number of included genes, whereby future investigations would potentially generate an augmented primary gene list. Importantly, in vitro, in vivo, and clinical validations are the vital parts of testing our presented hypothesis-generating approach. More specifically, in vitro validations can be checked by expression and regulatory experiments, in vivo validations can be designed on knock down/known out of CpG-PGx SNPs in the animal of interest (mouse, rat, rabbit) and monitoring the drug’s effects on the living body; furthermore, clinical validations can be checked on individuals receiving specific drugs who performed Epigenomics or epigenetic molecular detection on the suggested CpG-PGx SNP(s). All of these validations can be widened to trans-regulation interactions of both potential CpG-PGx SNPs and possible CpG-PGx SNPs; more clearly, a forming CpG site SNP should be verified for its new positive/negative binding affinities. We believe it is plausible that CpG islands would help predict CpG-PGx SNPs in future investigations. Obviously, both clinical and real-world confirmations are highly recommended for validating our findings.