The Genetics behind Sulfation: Impact on Airway Remodeling

Abstract

1. Introduction

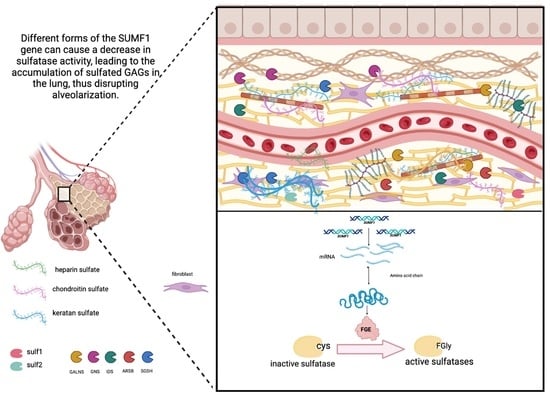

2. Alveolar Formation

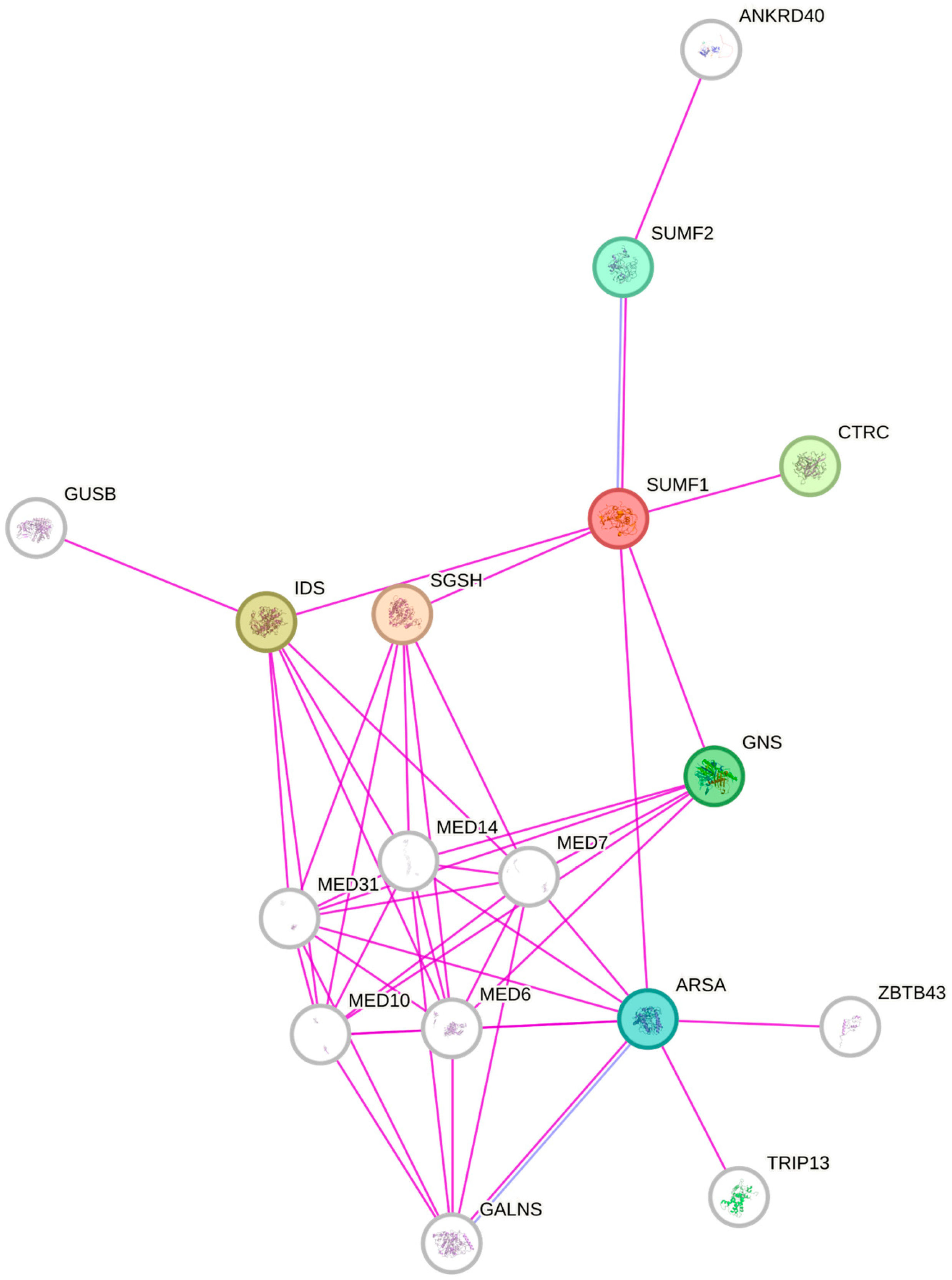

3. Sulfatases Pivotal in Extracellular Matrix Remodeling

4. Sulfatase Modifying Factor 1—The Master Regulator of Sulfatases Activity

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions—Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Banno, A.; Reddy, A.T.; Lakshmi, S.P.; Reddy, R.C. Bidirectional interaction of airway epithelial remodeling and inflammation in asthma. Clin. Sci. 2020, 134, 1063–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, S.P.; Agusti, A.; Bafadhel, M.; Christenson, S.A.; Bon, J.; Donaldson, G.C.; Sin, D.D.; Wedzicha, J.A.; Martinez, F.J. Phenotypes, Etiotypes, and Endotypes of Exacerbations of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2023, 208, 1026–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaeloudes, C.; Abubakar-Waziri, H.; Lakhdar, R.; Raby, K.; Dixey, P.; Adcock, I.M.; Mumby, S.; Bhavsar, P.K.; Chung, K.F. Molecular mechanisms of oxidative stress in asthma. Mol. Asp. Med. 2022, 85, 101026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, J.; Meng, Y.; Adcock, I.M.; Yao, X. Role of inflammatory cells in airway remodeling in COPD. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2018, 13, 3341–3348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viegi, G.; Maio, S.; Fasola, S.; Baldacci, S. Global Burden of Chronic Respiratory Diseases. J. Aerosol Med. Pulm. Drug Deliv. 2020, 33, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mookerjee, N.; Schmalbach, N.; Antinori, G.; Thampi, S.; Windle-Puente, D.; Gilligan, A.; Huy, H.; Andrews, M.; Sun, A.; Gandhi, R.; et al. Association of Risk Factors and Comorbidities with Chronic Pain in the Elderly Population. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2024, 15, 21501319241233463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercado, N.; Ito, K.; Barnes, P.J. Accelerated ageing of the lung in COPD: New concepts. Thorax 2015, 70, 482–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, M.O.S.; Souza, A.L.C.S.; Carvalho, M.B.; Pacheco, A.P.A.S.; Rocha, L.C.; Nascimento, V.M.L.D.; Figueiredo, C.V.B.; Guarda, C.C.; Santiago, R.P.; Adekile, A.; et al. Evaluation of Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Levels and SERPINA1 Gene Polymorphisms in Sickle Cell Disease. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragland, M.F.; Benway, C.J.; Lutz, S.M.; Bowler, R.P.; Hecker, J.; Hokanson, J.E.; Crapo, J.D.; Castaldi, P.J.; DeMeo, D.L.; Hersh, C.P.; et al. Genetic Advances in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Insights from COPDGene. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 200, 677–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonough, J.E.; Yuan, R.; Suzuki, M.; Seyednejad, N.; Elliott, W.M.; Sanchez, P.G.; Wright, A.C.; Gefter, W.B.; Litzky, L.; Coxson, H.O.; et al. Small-Airway Obstruction and Emphysema in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 365, 1567–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mebratu, Y.A.; Smith, K.R.; Agga, G.E.; Tesfaigzi, Y. Inflammation and emphysema in cigarette smoke-exposed mice when instilled with poly (I:C) or infected with influenza A or respiratory syncytial viruses. Respir. Res. 2016, 17, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soma, T.; Nagata, M. Immunosenescence, Inflammaging, and Lung Senescence in Asthma in the Elderly. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wernersson, S.; Pejler, G. Mast cell secretory granules: Armed for battle. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2014, 14, 478–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radermecker, C.; Sabatel, C.; Vanwinge, C.; Ruscitti, C.; Maréchal, P.; Perin, F.; Schyns, J.; Rocks, N.; Toussaint, M.; Cataldo, D.; et al. Locally instructed CXCR4hi neutrophils trigger environment-driven allergic asthma through the release of neutrophil extracellular traps. Nat. Immunol. 2019, 20, 1444–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Muhsen, S.; Johnson, J.R.; Hamid, Q. Remodeling in asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2011, 128, 451–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hough, K.P.; Curtiss, M.L.; Blain, T.J.; Liu, R.-M.; Trevor, J.; Deshane, J.S.; Thannickal, V.J. Airway Remodeling in Asthma. Front. Med. 2020, 7, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, I.; Kinnula, V.L.; Gorbunova, V.; Yao, H. SIRT1 as a therapeutic target in inflammaging of the pulmonary disease. Prev. Med. 2012, 54, S20–S28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhan, Y.; Huang, Q.; Deng, Z.; Chen, S.; Yang, R.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, M.; Wu, J.; Gu, Y.; et al. DNA hypomethylation-mediated upregulation of GADD45B facilitates airway inflammation and epithelial cell senescence in COPD. J. Adv. Res. 2024; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thun, G.A.; Imboden, M.; Ferrarotti, I.; Kumar, A.; Obeidat, M.; Zorzetto, M.; Haun, M.; Curjuric, I.; Alves, A.C.; Jackson, V.E.; et al. Causal and Synthetic Associations of Variants in the SERPINA Gene Cluster with Alpha1-antitrypsin Serum Levels. PLOS Genet. 2013, 9, e1003585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Zhang, H.; Xu, Y.; Ding, Y.; Chen, X.; Mei, Z.; Ding, H.; Jie, Z. Association among genetic polymorphisms of GSTP1, HO-1, and SOD-3 and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease susceptibility. SSRN Electron. J. 2019, 14, 2081–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reséndiz-Hernández, J.M.; Falfán-Valencia, R. Genetic polymorphisms and their involvement in the regulation of the inflammatory response in asthma and COPD. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2018, 27, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacheva, T.; Dimov, D.; Anastasov, A.; Zhelyazkova, Y.; Kurzawski, M.; Gulubova, M.; Drozdzik, M.; Vlaykova, T. Association of the MMP7-181A>G promoter polymorphism with early onset of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Balk. J. Med. Genet. 2017, 20, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Haq, I.; Chappell, S.; Johnson, S.R.; Lotya, J.; Daly, L.; Morgan, K.; Guetta-Baranes, T.; Roca, J.; Rabinovich, R.; Millar, A.B.; et al. Association of MMP-12 polymorphisms with severe and very severe COPD: A case control study of MMPs-1, 9 and 12in a European population. BMC Med. Genet. 2010, 11, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; He, L.; Zhu, Z.; Yang, F.; Ma, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liu, X. The mechanism of gut-lung axis in pulmonary fibrosis. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1258246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walma, D.A.C.; Yamada, K.M. The extracellular matrix in development. Development 2020, 147, dev175596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, E.; Song, Y.; Zhang, F.; Asarian, L.; Downs, I.; Young, B.; Han, X.; Ouyang, Y.; Xia, K.; Linhardt, R.J.; et al. Regional and disease-specific glycosaminoglycan composition and function in decellularized human lung extracellular matrix. Acta Biomater. 2023, 168, 388–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garantziotis, S.; Savani, R.C. Hyaluronan biology: A complex balancing act of structure, function, location and context. Matrix Biol. 2019, 78–79, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esko, J.D.; Lindahl, U. Molecular diversity of heparan sulfate. J. Clin. Investig. 2001, 108, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bülow, H.E.; Hobert, O. The Molecular Diversity of Glycosaminoglycans Shapes Animal Development. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2006, 22, 375–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diez-Roux, G.; Ballabio, A. Sulfatases and human disease. Annu. Rev. Genom. Hum. Genet. 2005, 6, 355–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godoy-Guzmán, C.; Martin, S.S.; Pereda, J. Proteoglycan and collagen expression during human air conducting system development. Eur. J. Histochem. 2012, 56, e29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- I Izvolsky, K.; Shoykhet, D.; Yang, Y.; Yu, Q.; A Nugent, M.; Cardoso, W.V. Heparan sulfate–FGF10 interactions during lung morphogenesis. Dev. Biol. 2003, 258, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamhi, E.; Joo, E.J.; Dordick, J.S.; Linhardt, R.J. Glycosaminoglycans in infectious disease. Biol. Rev. 2013, 88, 928–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, P.; Zhang, Z.; Degeest, G.; Mortier, E.; Leenaerts, I.; Coomans, C.; Schulz, J.; N’kuli, F.; Courtoy, P.J.; David, G. Syndecan Recyling Is Controlled by Syntenin-PIP2 Interaction and Arf6. Dev. Cell 2005, 9, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, S.; Martínez-Burgo, B.; Sepuru, K.M.; Rajarathnam, K.; Kirby, J.A.; Sheerin, N.S.; Ali, S. Regulation of Chemokine Function: The Roles of GAG-Binding and Post-Translational Nitration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papakonstantinou, E.; Klagas, I.; Roth, M.; Tamm, M.; Stolz, D. Acute Exacerbations of COPD Are Associated with Increased Expression of Heparan Sulfate and Chondroitin Sulfate in BAL. Chest 2016, 149, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smits, N.C.; Shworak, N.W.; Dekhuijzen, P.R.; van Kuppevelt, T.H. Heparan Sulfates in the Lung: Structure, Diversity, and Role in Pulmonary Emphysema. Anat. Rec. 2010, 293, 955–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shannon, J.M.; McCormick-Shannon, K.; Burhans, M.S.; Shangguan, X.; Srivastava, K.; Hyatt, B.A. Chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans are required for lung growth and morphogenesis in vitro. Am. J. Physiol. Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2003, 285, L1323–L1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Srinoulprasert, Y.; Kongtawelert, P.; Chaiyaroj, S.C. Chondroitin sulfate B and heparin mediate adhesion of Penicillium marneffei conidia to host extracellular matrices. Microb. Pathog. 2006, 40, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosen, S.D.; Lemjabbar-Alaoui, H. Sulf-2: An extracellular modulator of cell signaling and a cancer target candidate. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2010, 14, 935–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, M.; Hosono-Fukao, T.; Tang, R.; Sugaya, N.; van Kuppevelt, T.H.; Jenniskens, G.J.; Kimata, K.; Rosen, S.D.; Uchimura, K. Direct detection of HSulf-1 and HSulf-2 activities on extracellular heparan sulfate and their inhibition by PI-88. Glycobiology 2009, 20, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, R.; Rosen, S.D. Functional Consequences of the Subdomain Organization of the Sulfs. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 21505–21514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morimoto-Tomita, M.; Uchimura, K.; Werb, Z.; Hemmerich, S.; Rosen, S.D. Cloning and characterisation of two extracellular heparin-degrading endosulfatases in mice and humans. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 49175–49185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohto, T.; Uchida, H.; Yamazaki, H.; Keino-Masu, K.; Matsui, A.; Masu, M. Identification of a novel nonlysosomal sulphatase expressed in the floor plate, choroid plexus and cartilate. Genes Cells 2002, 7, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambasta, R.K.; Ai, X.; Emerson, C.P. Quail Sulf1 Function Requires Asparagine-linked Glycosylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 34492–34499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.H.; Banini, B.A.; Asumda, F.Z.; Campbell, N.A.; Hu, C.; Moser, C.D.; Shire, A.M.; Han, S.; Ma, C.; Krishnan, A.; et al. Knockout of sulfatase 2 is associated with decreased steatohepatitis and fibrosis in a mouse model of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Am. J. Physiol. Liver Physiol. 2020, 319, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, I.; Asumda, F.Z.; Moser, C.D.; Kang, Y.N.N.; Lai, J.-P.; Roberts, L.R. Sulfatase-2 Regulates Liver Fibrosis through the TGF-β Signaling Pathway. Cancers 2021, 13, 5279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, T.; Keino-Masu, K.; Nagamine, S.; Kametani, F.; Ohto, T.; Hasegawa, M.; van Kuppevelt, T.H.; Kunita, S.; Takahashi, S.; Masu, M. Desulfation of Heparan Sulfate by Sulf1 and Sulf2 Is Required for Corticospinal Tract Formation. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 13847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosma, M.P.; Pepe, S.; Annunziata, I.; Newbold, R.F.; Grompe, M.; Parenti, G.; Ballabio, A. The Multiple Sulfatase Deficiency Gene Encodes an Essential and Limiting Factor for the Activity of Sulfatases. Cell 2003, 113, 445–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dierks, T.; Schmidt, B.; Borissenko, L.V.; Peng, J.; Preusser, A.; Mariappan, M.; Von Figura, K. Multiple Sulfatase Deficiency Is Caused by Mutations in the Gene Encoding the Human C-Formylglycine Generating Enzyme thyosis, and chondrodysplasia punctata (Hopwood and Ballabio, 2001). Mammalian cells synthesize sulfatases at ribosomes bound to the endoplasmic reticulum. During or shortly after protein translocation and while the sulfatase poly-of P23 with extracts from microsomes of bovine pan. Cell 2003, 113, 435–444. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, B.; Selmer, T.; Ingendoh, A.; von Figurat, K. A novel amino acid modification in sulfatases that is defective in multiple sulfatase deficiency. Cell 1995, 82, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zito, E.; Fraldi, A.; Pepe, S.; Annunziata, I.; Kobinger, G.; Di Natale, P.; Ballabio, A.; Cosma, M.P. Sulphatase activities are regulated by the interaction of sulphatase-modifying factor 1 with SUMF2. Embo Rep. 2005, 6, 655–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caird, R.; Williamson, M.; Yusuf, A.; Gogoi, D.; Casey, M.; McElvaney, N.G.; Reeves, E.P. Targeting of Glycosaminoglycans in Genetic and Inflammatory Airway Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraldi, A.; Biffi, A.; Lombardi, A.; Visigalli, I.; Pepe, S.; Settembre, C.; Nusco, E.; Auricchio, A.; Naldini, L.; Ballabio, A.; et al. SUMF1 enhances sulfatase activities in vivo in five sulfatase deficiencies. Biochem. J. 2007, 403, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zito, E.; Buono, M.; Pepe, S.; Settembre, C.; Annunziata, I.; Surace, E.M.; Dierks, T.; Monti, M.; Cozzolino, M.; Pucci, P.; et al. Sulfatase modifying factor 1 trafficking through the cells: From endoplasmic reticulum to the endoplasmic reticulum. EMBO J. 2007, 26, 2443–2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Settembre, C.; Arteaga-Solis, E.; McKee, M.D.; de Pablo, R.; Al Awqati, Q.; Ballabio, A.; Karsenty, G. Proteoglycan desulfation determines the efficiency of chondrocyte autophagy and the extent of FGF signaling during endochondral ossification. Genes Dev. 2008, 22, 2645–2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Settembre, C.; Annunziata, I.; Spampanato, C.; Zarcone, D.; Cobellis, G.; Nusco, E.; Zito, E.; Tacchetti, C.; Cosma, M.P.; Ballabio, A. Systemic inflammation and neurodegeneration in a mouse model of multiple sulfatase deficiency. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 4506–4511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arteaga-Solis, E.; Settembre, C.; Ballabio, A.; Karsenty, G. Sulfatases are determinants of alveolar formation. Matrix Biol. 2012, 31, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Weidner, J.; Jarenbäck, L.; de Jong, K.; Vonk, J.M.; Berge, M.v.D.; Brandsma, C.-A.; Boezen, H.M.; Sin, D.; Bossé, Y.; Nickle, D.; et al. Sulfatase modifying factor 1 (SUMF1) is associated with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Respir. Res. 2017, 18, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roth-Kleiner, M.; Post, M. Similarities and dissimilarities of branching and septation during lung development. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2005, 40, 113–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarenbäck, L.; Frantz, S.; Weidner, J.; Ankerst, J.; Nihlén, U.; Bjermer, L.; Wollmer, P.; Tufvesson, E. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the sulfatase-modifying factor 1 gene are associated with lung function and COPD. ERJ Open Res. 2022, 8, 00668–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; McDonald, M.-L.N.; Cho, M.H.; Wan, E.S.; Castaldi, P.J.; Hunninghake, G.M.; Marchetti, N.; A Lynch, D.; Crapo, J.D.; A Lomas, D.; et al. DNAH5 is associated with total lung capacity in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir. Res. 2014, 15, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dierks, T.; Dickmanns, A.; Preusser-Kunze, A.; Schmidt, B.; Mariappan, M.; von Figura, K.; Ficner, R.; Rudolph, M.G. Molecular Basis for Multiple Sulfatase Deficiency and Mechanism for Formylglycine Generation of the Human Formylglycine-Generating Enzyme. Cell 2005, 121, 541–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlotawa, L.; Ennemann, E.C.; Radhakrishnan, K.; Schmidt, B.; Chakrapani, A.; Christen, H.-J.; Moser, H.; Steinmann, B.; Dierks, T.; Gärtner, J. SUMF1 mutations affecting stability and activity of formylglycine generating enzyme predict clinical outcome in multiple sulfatase deficiency. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2011, 19, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickmanns, A.; Schmidt, B.; Rudolph, M.G.; Mariappan, M.; Dierks, T.; von Figura, K.; Ficner, R. Crystal Structure of Human pFGE, the Paralog of the Cα-formylglycine-generating Enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 15180–15187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, C.; Beecham, A.; Wang, L.; Slifer, S.; Wright, C.B.; Blanton, S.H.; Rundek, T.; Sacco, R.L. Genetic loci for blood lipid levels identified by linkage and association analyses in Caribbean Hispanics. J. Lipid Res. 2011, 52, 1411–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, J.F.; Meyer, N.J.; Qu, L.; Xue, C.; Liu, Y.; DerOhannessian, S.L.; Rushefski, M.; Paschos, G.K.; Tang, S.; Schadt, E.E.; et al. Integrative genomics identifies 7p11.2 as a novel locus for fever and clinical stress response in humans. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014, 24, 1801–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gande, S.L.; Mariappan, M.; Schmidt, B.; Pringle, T.H.; von Figura, K.; Dierks, T. Paralog of the formylglycine-generating enzyme–retention in the endoplasmic reticulum by canonical and noncanonical signals. FEBS J. 2008, 275, 1118–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mariappan, M.; Preusser-Kunze, A.; Balleininger, M.; Eiselt, N.; Schmidt, B.; Gande, S.L.; Wenzel, D.; Dierks, T.; von Figura, K. Expression, Localization, Structural, and Functional Characterization of pFGE, the Paralog of the Cα-Formylglycine-generating Enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 15173–15179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preusser-Kunze, A.; Mariappan, M.; Schmidt, B.; Gande, S.L.; Mutenda, K.; Wenzel, D.; von Figura, K.; Dierks, T. Molecular Characterization of the Human Cα-formylglycine-generating Enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 14900–14910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Li, Z.; Xue, L.; Jiang, X.; Liu, F. SUMF2 interacts with interleukin-13 and inhibits interleukin-13 secretion in bronchial smooth muscle cells. J. Cell. Biochem. 2009, 108, 1076–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royce, S.G.; Tan, L.; Koek, A.A.; Tang, M.L. Effect of extracellular matrix composition on airway epithelial cell and fibroblast structure: Implications for airway remodeling in asthma. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2009, 102, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farooq, M.; Khan, A.W.; Kim, M.S.; Choi, S. The Role of Fibroblast Growth Factor (FGF) Signaling in Tissue Repair and Regeneration. Cells 2021, 10, 3242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzy, R.D.; Stoilov, I.; Elton, T.J.; Mecham, R.P.; Ornitz, D.M. Fibroblast Growth Factor 2 Is Required for Epithelial Recovery, but Not for Pulmonary Fibrosis, in Response to Bleomycin. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2015, 52, 116–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, D.; Wang, L.; Jiang, P.; Kang, R.; Xie, Y. Correlation between hs-CRP, IL-6, IL-10, ET-1, and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Combined with Pulmonary Hypertension. J. Healthc. Eng. 2022, 2022, 3247807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranenburg, A.R.; Willems-Widyastuti, A.; Mooi, W.J.; Saxena, P.R.; Sterk, P.J.; I de Boer, W.; Sharma, H.S. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is associated with enhanced bronchial expression of FGF-1, FGF-2, and FGFR-1. J. Pathol. 2005, 206, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Zhou, F.; Zheng, D.; Wang, D.; Li, X.; Zhao, C.; Huang, X. FGF/FGFR signaling: From lung development to respiratory diseases. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2021, 62, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papakonstantinou, E.; Karakiulakis, G. The ‘sweet’ and ‘bitter’ involvement of glycosaminoglycans in lung diseases: Pharmacotherapeutic relevance. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2009, 157, 1111–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizumoto, S.; Fongmoon, D.; Sugahara, K. Interaction of chondroitin sulfate and dermatan sulfate from various biological sources with heparin-binding growth factors and cytokines. Glycoconj. J. 2013, 30, 619–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, H.-Y.; Olson, S.K.; Esko, J.D.; Horvitz, H.R. Caenorhabditis elegans early embryogenesis and vulval morphogenesis require chondroitin biosynthesis. Nature 2003, 423, 439–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iozzo, R.V. MATRIX PROTEOGLYCANS: From Molecular Design to Cellular Function. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1998, 67, 609–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kai, Y.; Yoneyama, H.; Koyama, J.; Hamada, K.; Kimura, H.; Matsushima, K. Treatment with chondroitinase ABC alleviates bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Med. Mol. Morphol. 2007, 40, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizuguchi, S.; Uyama, T.; Kitagawa, H.; Nomura, K.H.; Dejima, K.; Gengyo-Ando, K.; Mitani, S.; Sugahara, K.; Nomura, K. Chondroitin proteoglycans are involved in cell division of Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 2003, 423, 443–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souza-Fernandes, A.B.; Pelosi, P.; Rocco, P.R. Bench-to-bedside review: The role of glycosaminoglycans in respiratory disease. Crit. Care 2006, 10, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, S.; Gao, H.; He, T.; Li, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, L.; Chen, J.; Xie, Y.; Bao, J.; Gao, Y.; et al. Association between SUMF1 polymorphisms and COVID-19 severity. BMC Genet. 2023, 24, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, A.N.; Li, X.; A Largaespada, D.; Sato, A.; Kaneda, A.; Zurawski, S.M.; Doyle, E.L.; Milatovich, A.; Francke, U.; Copeland, N.G. Structural comparison and chromosomal localization of the human and mouse IL-13 genes. J. Immunol. 1993, 150, 5436–5444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ntenti, C.; Papakonstantinou, E.; Fidani, L.; Stolz, D.; Goulas, A. The Genetics behind Sulfation: Impact on Airway Remodeling. J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, 248. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm14030248

Ntenti C, Papakonstantinou E, Fidani L, Stolz D, Goulas A. The Genetics behind Sulfation: Impact on Airway Remodeling. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2024; 14(3):248. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm14030248

Chicago/Turabian StyleNtenti, Charikleia, Eleni Papakonstantinou, Liana Fidani, Daiana Stolz, and Antonis Goulas. 2024. "The Genetics behind Sulfation: Impact on Airway Remodeling" Journal of Personalized Medicine 14, no. 3: 248. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm14030248

APA StyleNtenti, C., Papakonstantinou, E., Fidani, L., Stolz, D., & Goulas, A. (2024). The Genetics behind Sulfation: Impact on Airway Remodeling. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 14(3), 248. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm14030248