Challenges in Septic Shock: From New Hemodynamics to Blood Purification Therapies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Improvement Programs in Sepsis: Early Recognition and Rescue

3. Dynamic Resuscitation in Sepsis in the Context of Fluid Tolerance

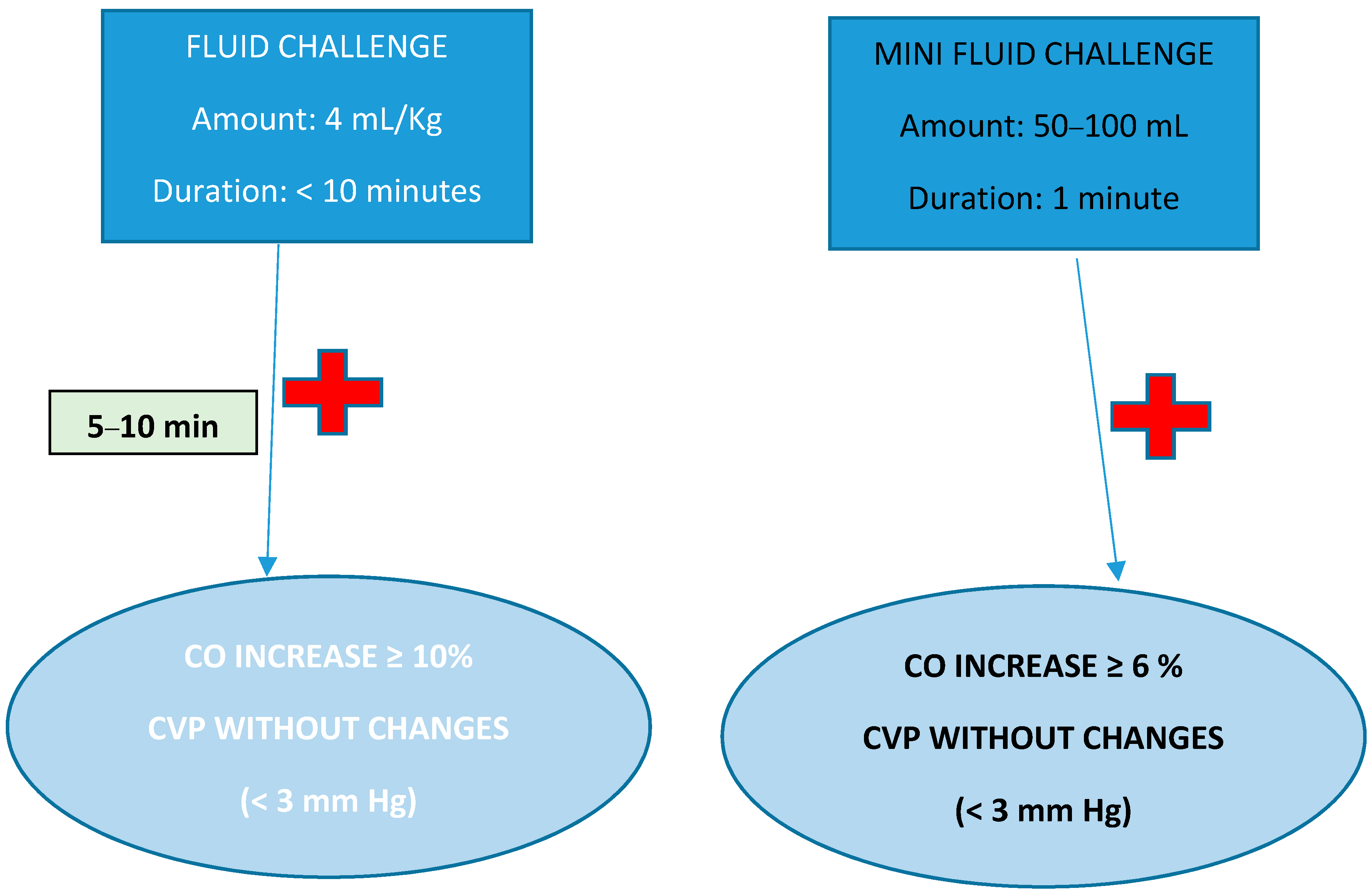

4. Fluid Responsiveness in Sepsis

- –

- Passive leg raising: reproduces the hemodynamic effects of a bolus of 300 mL volume, with a patient with a 10% increase in ≥CO being a volume responder [58].

- –

- End expiratory occlusion test: Consists of interrupting mechanical ventilation for a few seconds, observing the effect produced on OC. With this technique, the expected thresholds in CO variation are lower. A 5% increase is considered a volume response.

- –

- Tidal volume (Tv) challenge from 6 to 8 mL/kg ideal weight for 1 min in patients undergoing mechanical ventilation. It is considered positive when CO increases ≥3.5% [59].

- –

- Cyclic variations: stroke volume variation (SVV) or pulse pressure variation (PPV) during the respiratory cycle.

5. Macrohemodynamic Targets; Diastolic Blood Pressure; Vasoconstrictors: Norepinephrine and Vasopressin

- –

- MAP: The primary goal of resuscitation should always be tissue perfusion. Under normal conditions, the distribution of blood flow is controlled by metabolic demand through a self-regulating mechanism that is able to divert flow to organs or systems with high oxygen demand. In patients with sepsis, due to the high heterogeneity of organ and system involvement, together with the inflammatory state in which they are found, these mechanisms fail and perfusion becomes more dependent on pressure, which depends directly on MAP [62]. The SSC recommends an MAP of 65 mmHg as the lowest initial intervention threshold. From this threshold onwards, it should be individualized according to each patient [3,63].

- –

- Diastolic arterial pressure (DAP): One of the main mechanisms of hypotension and hypoperfusion in septic shock is decreased vasomotor tone. In these cases, DAP reflects vasodilation better than systolic arterial pressure (PAS) or MAP. The severity of vasodilation could influence therapeutic decisions, such as the early introduction of vasoactive agents, which would theoretically avoid unnecessary fluid administration and rapidly restore tissue perfusion [65].

- ✓

- What vasopressors do I use?

- Norepinephrine (NE) remains the most widely used vasopressor and the one recommended by the SSC as the first line [3]. Norepinephrine (NE) is both an alpha1- and beta1-agonist, and is therefore able to increase vascular tone and contractility. NE can improve microcirculatory flow by increasing perfusion pressure in hypotensive patients but can also decrease flow due to excessive vasoconstriction in high doses [68].

- The SSC recommends vasopressin (AVP) as a second-line vasopressor. The SSC suggests adding vasopressin to the NE (weak recommendation, low-quality evidence) with the intention of increasing the MAP or decreasing the dose of NE. This could prevent the deleterious consequences of excessive adrenergic load [3]. Vasopressin has a hemodynamic profile beyond its vasoconstrictor effect, related to its regional vasodilator effects at the renal and pulmonary levels that make it very attractive in several scenarios [69].

- ✓

- When do we start?

- Early administration could more quickly reverse the associated hypotension, preventing prolonged severe hypotension.

- Early infusion of NE could increase CO through several mechanisms: increasing preload in the early phase of septic shock and decreasing unstressed intravascular volume of capacitance vessels. In addition, NE may increase CO by increasing cardiac contractility.

- Administration of NE can recruit microvasculature and improve microcirculation in cases of severe hypotension through increased organ perfusion pressure.

- Early administration could prevent the detrimental effects of volume overload.

- Finally, early NE administration could improve patient prognosis [72].

6. Hemodynamic Monitoring

- The coexistence of different types of shock, which can make differential diagnosis difficult.

- Available hemodynamic monitoring systems have limitations.

- Organ-specific perfusion biomarkers are not available.

- (a)

- Basic monitoring: Central venous catheter, arterial catheter, and initial echocardiographic assessment. Currently, an echocardiographic approach is preferred for the initial evaluation of shock. It provides information to guide the initial diagnosis and assess the response to initial therapy. It is an excellent tool for assessing the condition of the volume. A major limitation of echocardiography is that the estimation of fill pressures is not very accurate and is more suitable for semiquantitative analyses or sequential measurements, as well as in the absence of continuous monitoring.

- (b)

- Advanced monitoring: If the patient’s response to initial treatment is positive and the shock situation resolves, the use of additional monitoring systems is not necessary. If the response is insufficient or inadequate, respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) coexists, or right ventricular dysfunction develops, then more advanced hemodynamic monitoring is recommended to assess cardiopulmonary function and guide more delicate fluid management [76].

- ✓

- Noninvasive-to-minimally invasive monitors:

- ✓

- Invasive Monitoring:

- –

- Transpulmonary thermodilution systems:

7. Tissue Perfusion Monitoring: Lactate, Venoarterial Carbon Dioxide Gradient, and Capillary Refill Time

8. Hemodynamic Coherence

9. Nutrition in SEPSIS

- Calories:

- Proteins:

- Enteral vs. Parenteral Nutrition:

- Pharmaconutrition:

9.1. Current Nutrition Recommendations for Sepsis

Nutrition Stewardship

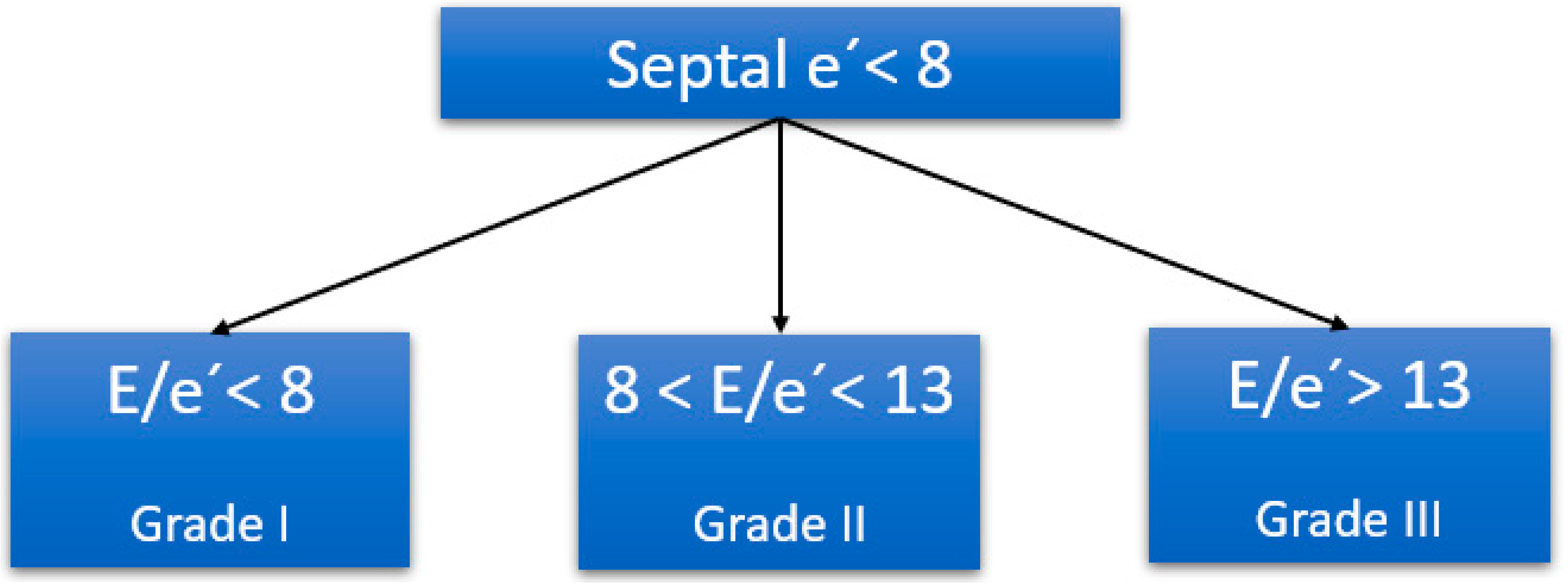

10. Myocardial Dysfunction in Sepsis

- –

- Systolic or diastolic ventricular dysfunction of the left and/or right ventricle;

- –

- CO preserved or diminished;

- –

- Arrhythmias.

- –

- Inflammatory and cardiac-depressant molecules: cytokines (especially tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and interleukin-1 (IL-1)), nitric oxide, prostanoids, and lipopolysaccharides (LPS).

- –

- Mitochondrial dysfunction and increased exosome secretion, leading to an increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS) and decreased adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production.

Cardiac Biomarkers in Sepsis

11. Role of Levosimendan in Sepsis

12. Role of Echocardiography in the Diagnosis, Resuscitation, and Management of Septic Patient Congestion

- (1)

- Differential diagnosis of the patient in shock;

- (2)

- Initial resuscitation of the patient with septic shock;

- (3)

- Managing the congestion or “evacuation” phase of sepsis.

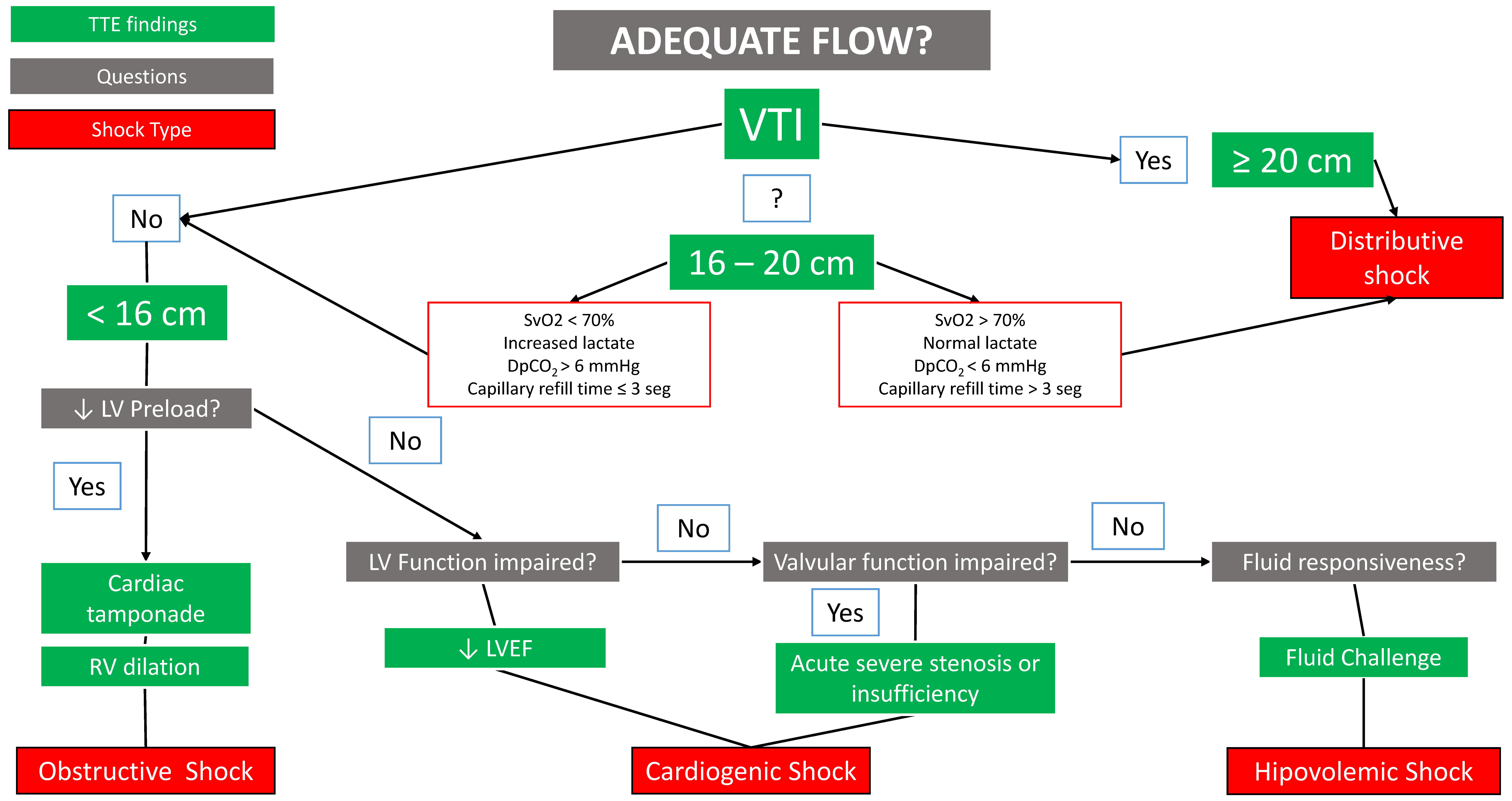

12.1. Differential Diagnosis of Shock

- –

- The order of the algorithm is not trivial: it is designed to avoid volume overload (for this reason, the last type of shock to be ruled out is hypovolemic).

- –

- Several shock mechanisms can coexist in the same patient, so the one considered the most predominant should be treated first, and the algorithm should always be completed to the end.

- –

- The algorithm does not cover 100% of shock causes.

12.2. Cardiac Ultrasound to Guide Resuscitation and Initial Management of Sepsis

- –

- Cluster 1 “Well resuscitated”: patients with preserved bilateral ventricular function and no fluid responsiveness.

- –

- Cluster 2 “LV systolic dysfunction”: compromised systolic function, low CO, higher dose of vasopressors, and no fluid responsiveness.

- –

- Cluster 3 “Hyperkinetic state”: preserved ventricular function, elevated CO, and no fluid responsiveness.

- –

- Cluster 4 “RV failure”: RV dysfunction and dilation, hypoxemia, and no fluid responsiveness.

- –

- Cluster 5 “Still hypovolemic”: preserved ventricular function, low CO, and fluid responsiveness.

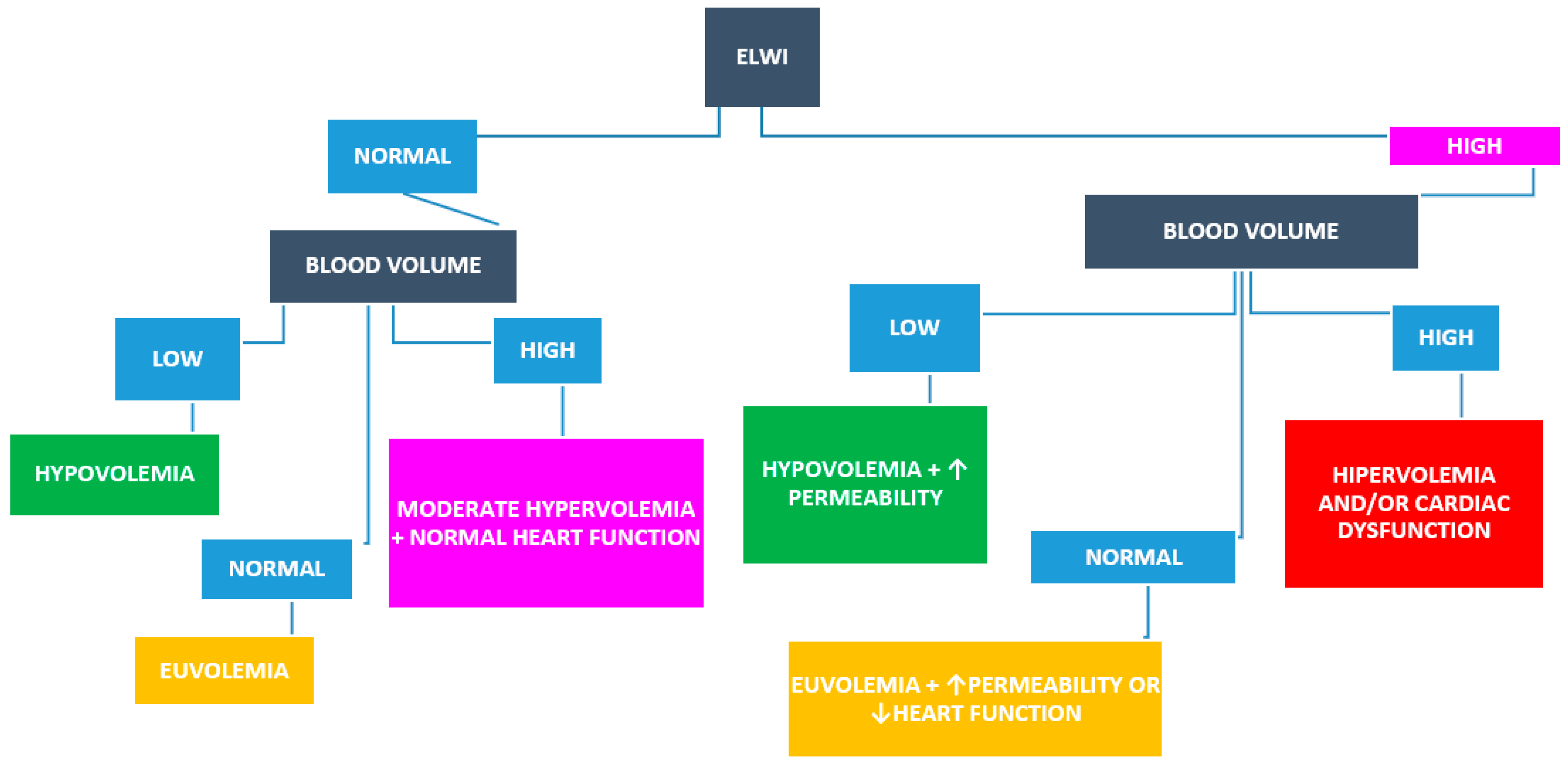

12.3. Volume Overload and Venous Congestion

- –

- The diameter of the inferior vena cava and its collapsibility.

- –

- Flow from the suprahepatic veins.

- –

- Portal vein flow.

- –

- The flow of intraparenchitmatous renal veins.

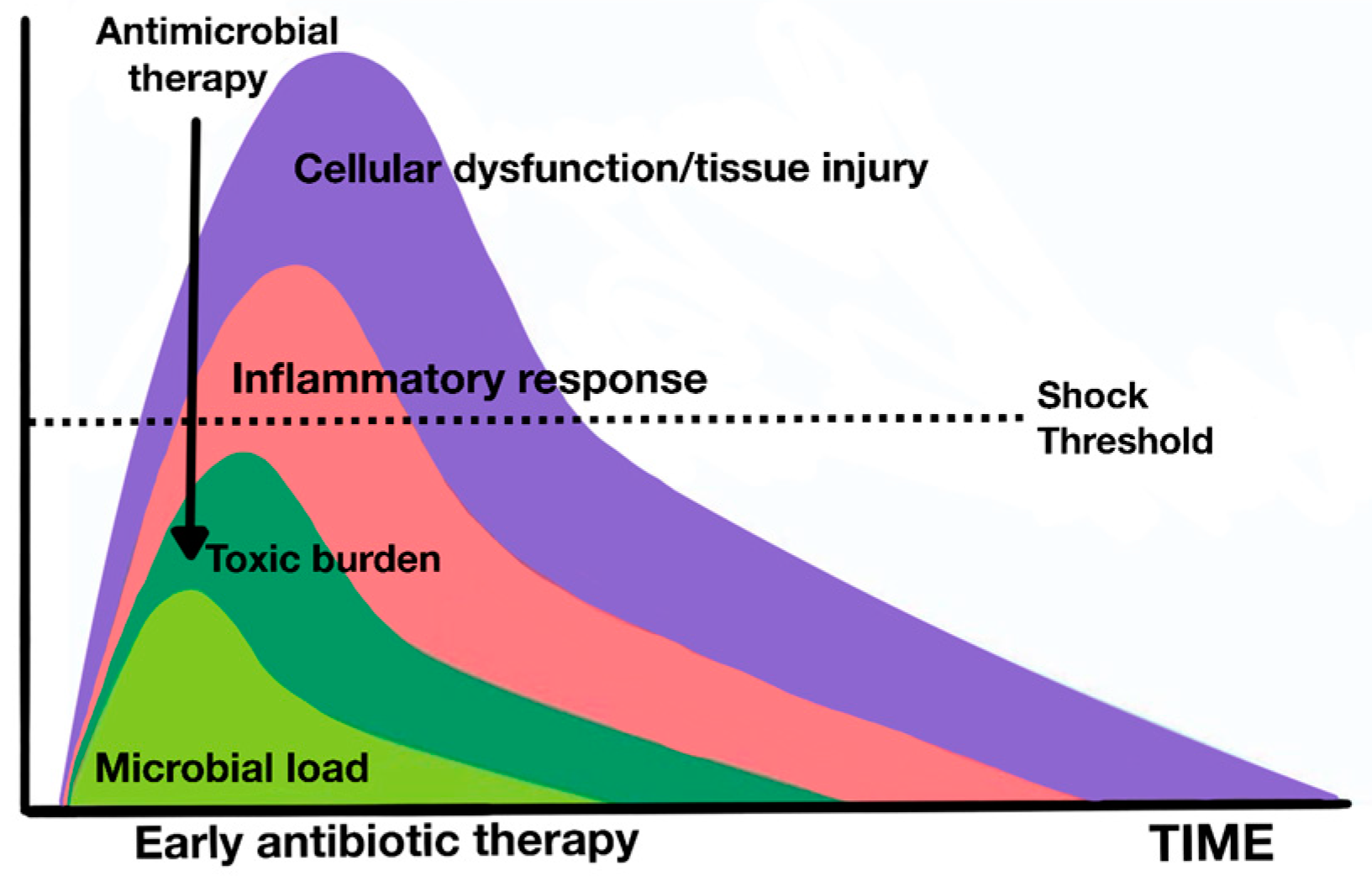

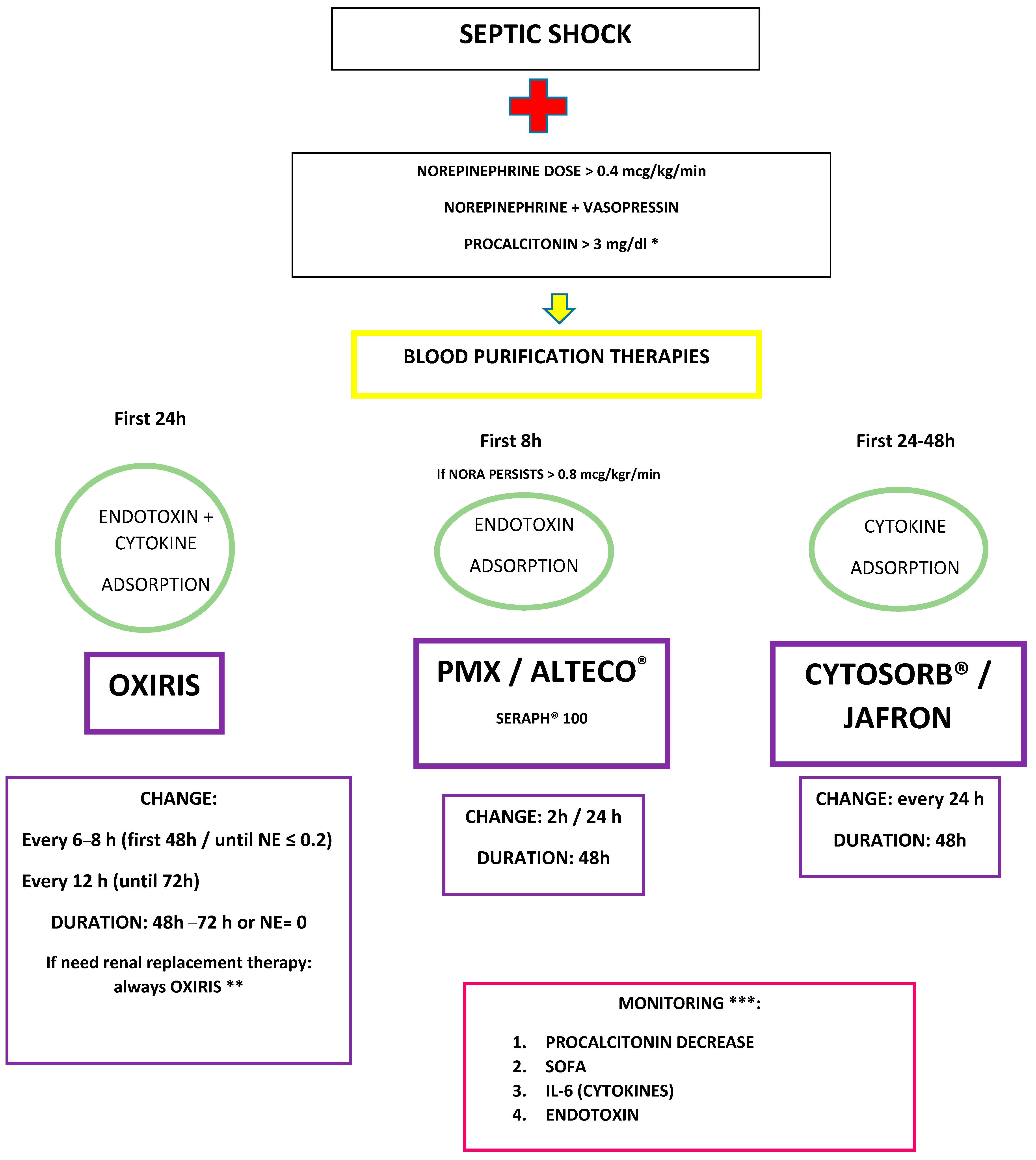

13. Blood Purification Therapies in Sepsis

13.1. Overview

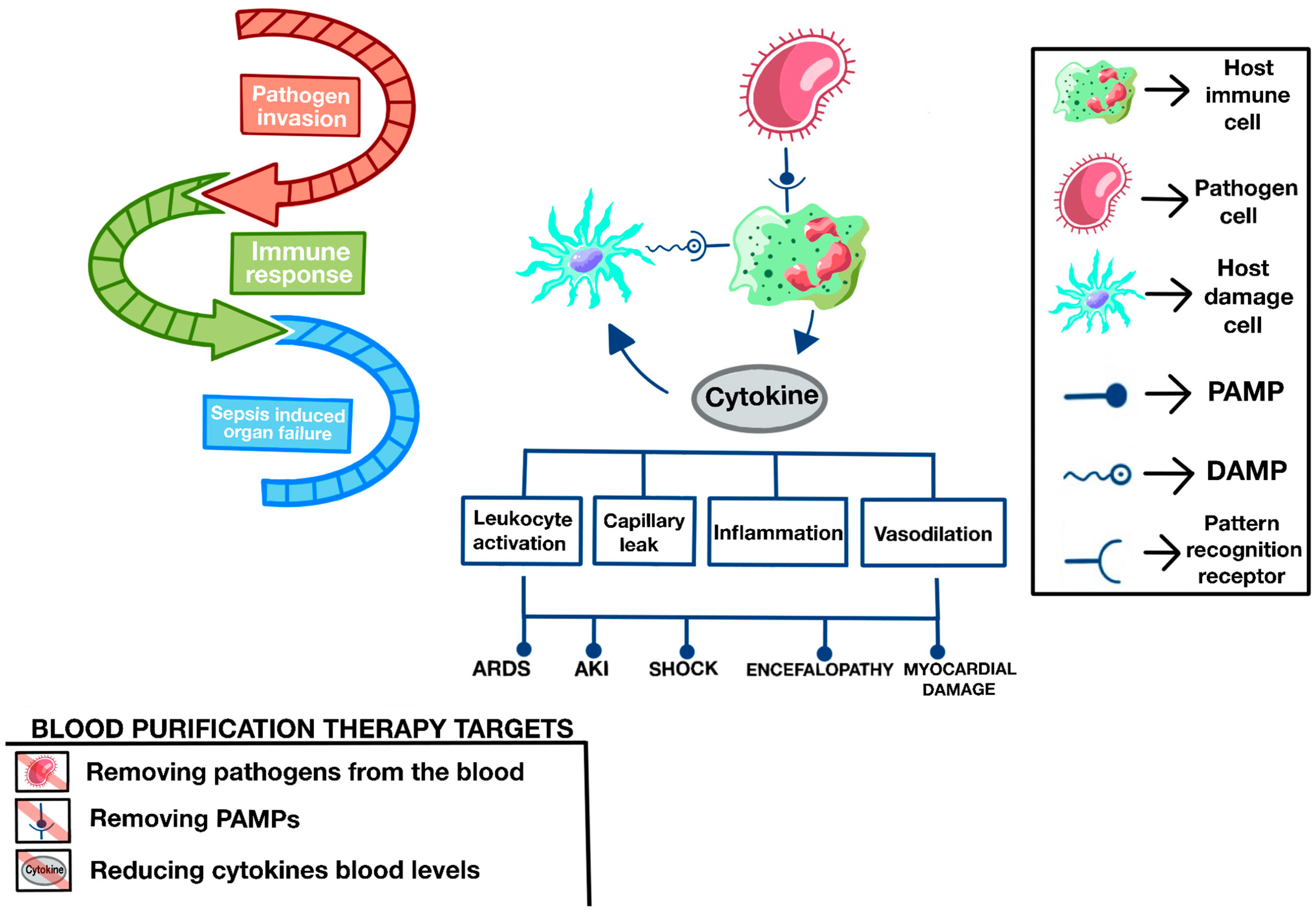

13.2. Rational of Blood Purification Therapies in Sepsis

13.3. Types of Blood Purification Therapies

- –

- Membranes that modulate the immune response to bacteria, mainly eliminating the endotoxin or the bacteria themselves.

- –

- Membranes that modulate the inflammatory response generated by the cells of the immune system, mainly by eliminating molecular patterns of damage and cytokines.

- –

- Membranes with both endotoxin removal possibilities, molecular standards, and cytokines.

13.4. Membranes That Modulate the Immune Response to Bacteria (Endotoxin/Bacteria)

13.5. Adsorption Systems That Remove Endotoxin

13.5.1. Polymyxin Membranes—TORAYMYXIN™

13.5.2. ALTECO® LPS Adsorber Membrane

13.5.3. Seraph® 100

13.6. Membranes That Modulate the Inflammatory Response Generated in the Immune System, Mainly by Eliminating Molecular Patterns of Damage and Cytokines

13.6.1. CYTOSORB®

13.6.2. JAFRON Medical

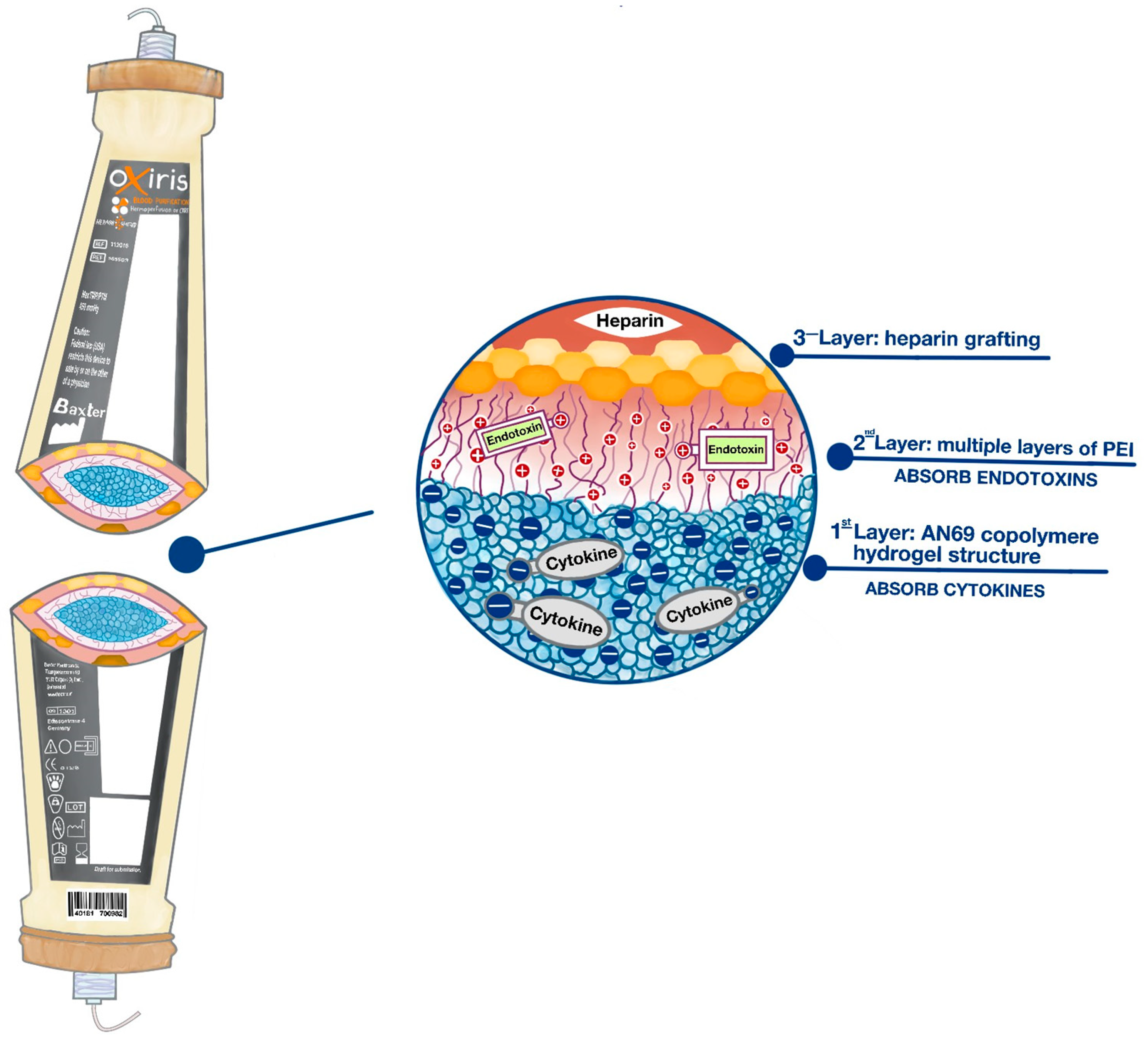

13.7. Membranes with Endotoxin-Scavenging Capabilities, Molecular Patterns, and Cytokines

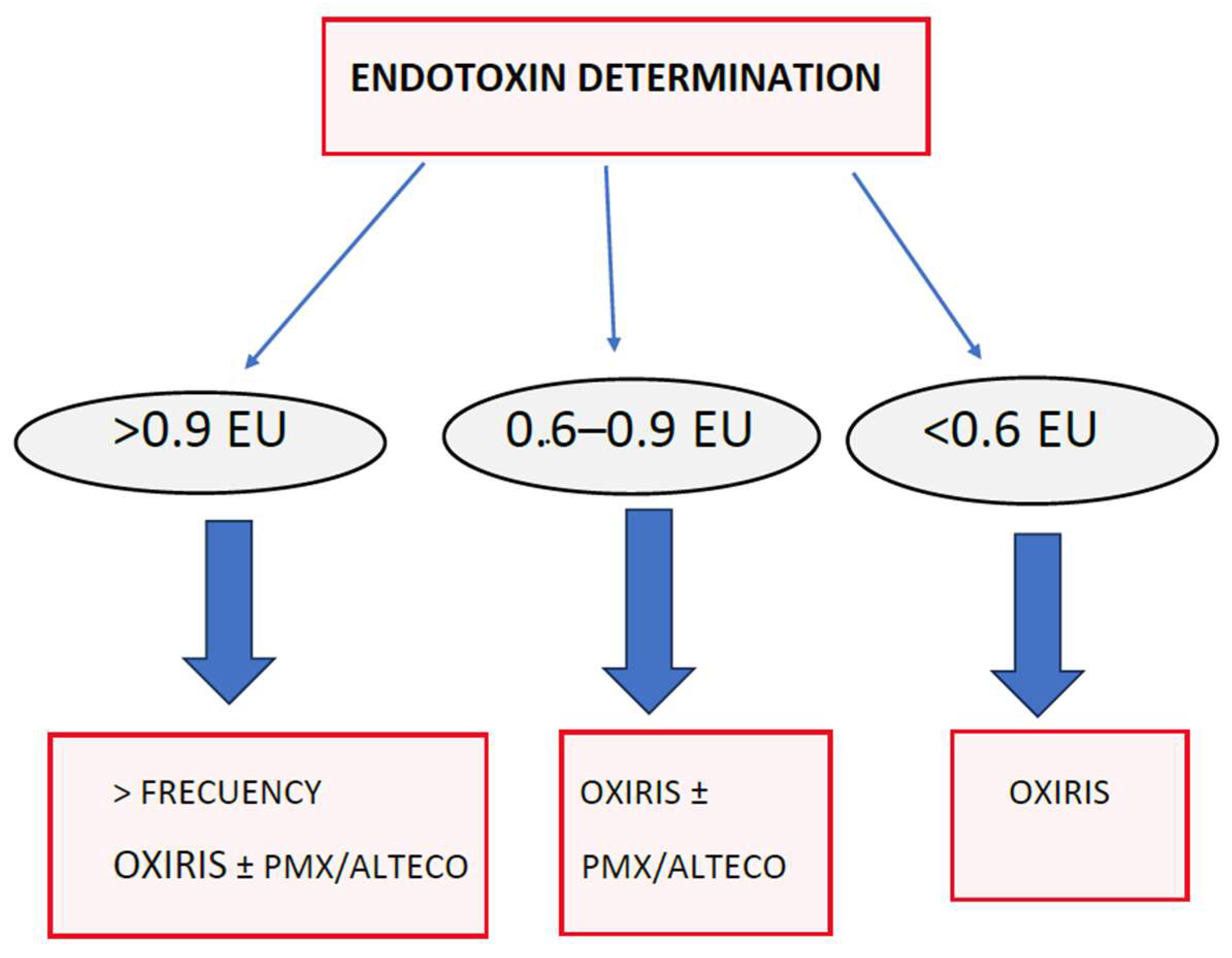

OXIRIS

13.8. Sequential or Synergistic Therapies with OXIRIS Adsorption Therapies

- Removing pathogens directly from the circulation, as with Seraph®.

- Eliminating PAMPs (the most emblematic endotoxins), as with TORAYMYXIN™, ALTECO®, and OXIRIS.

- Eliminating DAMPs (the most representative being HMGB1), as with OXIRIS, CYTOSORB®, and SERAPH, among others.

- Eliminating cytokines (interleukins and TNF-alpha, among many others) and immunomodulating the secondary response to microorganisms and PAMPs and DAMPs, as with OXIRIS, CYTOSORB®, and JAFRON.

- Extracorporeal organ support, mainly renal, but increasingly respiratory and cardiological.

14. Conclusions

- The challenges related to sepsis have to do with the balance between guidelines and evidence, with a personalized approach and in certain contexts. The high mortality rate of septic shock obligates us to explore cutting-edge therapies.

- Sepsis is a time-dependent pathology, and it is necessary to implement sepsis care programs to improve outcomes.

- Hemodynamics is directed toward personalized medicine and the recognition of different phenotypes to discover the timing of the initiation of vasopressor treatment and the appropriate dose of fluid therapy. The evaluation of perfusion, for example, with the capillary refill time, is key in clinical decision making.

- At present, the focus is not only on the initial timing but also on the so-called “deresuscitation”, with the early weaning of support therapies and targeted elimination of fluids. The novel concept of fluid tolerance is the new framework.

- Cardiac POCUS is a useful tool for the diagnosis and characterization of shock, the detection of myocardial dysfunction associated with sepsis, and for guiding fluid therapy in patients with sepsis.

- Blood purification therapies, mainly those aimed at eliminating endotoxins and cytokines, are becoming attractive in the early management of patients in septic shock. Sequential therapy of endotoxin and then cytokine removal with different devices; in parallel, eliminating both at the same time; or with the same purification system that eliminates both without the need for two devices, are promising strategies in certain phenotypes and with appropriate timing.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- De Backer, D.; Cecconi, M.; Lipman, J.; Machado, F.; Myatra, S.N.; Ostermann, M.; Perner, A.; Teboul, J.-L.; Vincent, J.-L.; Walley, K.R. Challenges in the management of septic shock: A narrative review. Intensive Care Med. 2019, 45, 420–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavaillon, J.; Singer, M.; Skirecki, T. Sepsis therapies: Learning from 30 years of failure of translational research to propose new leads. EMBO Mol. Med. 2020, 12, e10128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, L.; Rhodes, A.; Alhazzani, W.; Antonelli, M.; Coopersmith, C.M.; French, C.; Machado, F.R.; Mcintyre, L.; Ostermann, M.; Prescott, H.C.; et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: International guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock 2021. Intensive Care Med. 2021, 47, 1181–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gyawali, B.; Ramakrishna, K.; Dhamoon, A.S. Sepsis: The evolution in definition, pathophysiology, and management. SAGE Open Med. 2019, 7, 2050312119835043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivers, E.; Nguyen, B.; Havstad, S.; Ressler, J.; Muzzin, A.; Knoblich, B.; Peterson, E.; Tomlanovich, M. Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 345, 1368–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, J.; Kattan, E.; Annane, D.; Castro, R.; Cecconi, M.; De Backer, D.; Dubin, A.; Evans, L.; Gong, M.N.; Hamzaoui, O.; et al. Current practice and evolving concepts in septic shock resuscitation. Intensive Care Med. 2022, 48, 148–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, F.; Tarrant, C.; Hamilton, V.; Kiernan, F.M.; Jenkins, D.; Krockow, E.M. Sepsis and antimicrobial stewardship: Two sides of the same coin. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2019, 28, 758–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Waele, J.J.; Dhaese, S. Antibiotic stewardship in sepsis management: Toward a balanced use of antibiotics for the severely ill patient. Expert. Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2019, 17, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garduno, A.; Martín-Loeches, I. Efficacy and appropriateness of novel antibiotics in response to antimicrobial-resistant gram-negative bacteria in patients with sepsis in the ICU. Expert. Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2022, 20, 513–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schinkel, M.; Nanayakkara, P.W.B.; Wiersinga, W.J. Sepsis Performance Improvement Programs: From Evidence Toward Clinical Implementation. Crit. Care 2022, 26, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Waele, E.; Malbrain, M.L.; Spapen, H. Nutrition in Sepsis: A Bench-to-Bedside Review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nandhabalan, P.; Ioannou, N.; Meadows, C.; Wyncoll, D. Refractory septic shock: Our pragmatic approach. Crit. Care 2018, 22, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Backer, D.; Cecconi, M.; Chew, M.S.; Hajjar, L.; Monnet, X.; Ospina-Tascón, G.A.; Ostermann, M.; Pinsky, M.R.; Vincent, J.-L. A plea for personalization of the hemodynamic management of septic shock. Crit. Care 2022, 26, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kattan, E.; Bakker, J.; Estenssoro, E.; Ospina-Tascón, G.A.; Cavalcanti, A.B.; De Backer, D.; Vieillard-Baron, A.; Teboul, J.-L.; Castro, R.; Hernández, G.; et al. Hemodynamic phenotype-based, capillary refill time-targeted resuscitation in early septic shock: The ANDROMEDA-SHOCK-2 Randomized Clinical Trial study protocol. Rev. Bras. Ter. Intensive 2022, 34, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prescott, H.C.; Iwashyna, T.J. Improving Sepsis Treatment by Embracing Diagnostic Uncertainty. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2019, 16, 426–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuurman, A.R.; Sloot, P.M.A.; Wiersinga, W.J.; van der Poll, T. Embracing complexity in sepsis. Crit. Care 2023, 27, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, J.-L.; Singer, M.; Einav, S.; Moreno, R.; Wendon, J.; Teboul, J.-L.; Bakker, J.; Hernandez, G.; Annane, D.; de Man, A.M.E.; et al. Equilibrating SSC guidelines with individualized care. Crit. Care 2021, 25, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damiani, E.; Donati, A.; Serafini, G.; Rinaldi, L.; Adrario, E.; Pelaia, P.; Busani, S.; Girardis, M. Effect of performance improvement programs on compliance with sepsis bundles and mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0125827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrejón, E.P.; del Castillo, J.G.; Rueda, F.R.; González, F.J.; Artola, B.S.; von Wernitz Teleki, A.; Vidal, F.G.; Iglesias, P.R.; Redondo, G.B.; Serrano, D.A.R.; et al. Documento de consenso para la implantación y desarrollo del Código Sepsis en la Comunidad de Madrid. Rev. Esp. Quim. 2019, 32, 400–409. [Google Scholar]

- de Dios, B.; Borges, M.; Smith, T.D.; Del Castillo, A.; Socias, A.; Gutiérrez, L.; Nicolás, J.; Lladó, B.; Roche, J.A.; Díaz, M.P.; et al. Computerised sepsis protocol management. Description of an early warning system. Enfermedades Infecc. Microbiol. Clin. Engl. Ed. 2018, 36, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safe Patients, Smart Hospitals: How One Doctor’s Checklist Can Help Us Change Health Care from the Inside Out—Pronovost, Peter; Vohr, Eric: 9781594630644—AbeBooks. Available online: https://www.abebooks.com/9781594630644/Safe-Patients-Smart-Hospitals-Doctors-159463064X/plp (accessed on 25 August 2023).

- Méndez, R.; Figuerola, A.; Chicot, M.; Barrios, A.; Pascual, N.; Ramasco, F.; Rodríguez, D.; García, I.; von Wernitz, A.; Zurita, N.; et al. Sepsis Code: Dodging mortality in a tertiary hospital. Rev. Esp. Quim. Publ. Soc. Esp. Quim. 2022, 35, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bein, B.; Seewald, S.; Gräsner, J.-T. How to avoid catastrophic events on the ward. Best. Pr. Res. Clin. Anaesthesiol. 2016, 30, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lafonte, M.; Cai, J.; Lissauer, M.E. Failure to rescue in the surgical patient: A review. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 2019, 25, 706–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghaferi, A.A.; Dimick, J.B. Variation in mortality after high-risk cancer surgery: Failure to rescue. Surg. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 2012, 21, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, A.; Meier, J.; Bhat, A.; Balentine, C. Hospital Performance on Failure to Rescue Correlates with Likelihood of Home Discharge. J. Surg. Res. 2023, 287, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seymour, C.W.; Liu, V.X.; Iwashyna, T.J.; Brunkhorst, F.M.; Rea, T.D.; Scherag, A.; Rubenfeld, G.; Kahn, J.M.; Shankar-Hari, M.; Singer, M.; et al. Assessment of Clinical Criteria for Sepsis: For the Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA 2016, 315, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Cui, X.; Song, Z. Predicting Sepsis Onset in ICU Using Machine Learning Models: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Infect. Dis. 2023; Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michard, F.; Bellomo, R.; Taenzer, A. The rise of ward monitoring: Opportunities and challenges for critical care specialists. Intensive Care Med. 2019, 45, 671–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michard, F. Should we M.O.N.I.T.O.R ward patients differently? Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. EJA 2022, 39, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudd, K.E.; Johnson, S.C.; Agesa, K.M.; Shackelford, K.A.; Tsoi, D.; Kievlan, D.R.; Colombara, D.V.; Ikuta, K.S.; Kissoon, N.; Finfer, S.; et al. Global, regional, and national sepsis incidence and mortality, 1990–2017: Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 2020, 395, 200–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecconi, M.; Evans, L.; Levy, M.; Rhodes, A. Sepsis and septic shock. Lancet 2018, 392, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, J.-L.; De Backer, D. Circulatory Shock. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 1726–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hariri, G.; Joffre, J.; Leblanc, G.; Bonsey, M.; Lavillegrand, J.-R.; Urbina, T.; Guidet, B.; Maury, E.; Bakker, J.; Ait-Oufella, H. Narrative review: Clinical assessment of peripheral tissue perfusion in septic shock. Ann. Intensive Care 2019, 9, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malbrain, M.L.N.G.; Van Regenmortel, N.; Saugel, B.; De Tavernier, B.; Van Gaal, P.-J.; Joannes-Boyau, O.; Teboul, J.-L.; Rice, T.W.; Mythen, M.; Monnet, X. Principles of fluid management and stewardship in septic shock: It is time to consider the four D’s and the four phases of fluid therapy. Ann. Intensive Care 2018, 8, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monnet, X.; Lai, C.; Ospina-Tascon, G.; De Backer, D. Evidence for a personalized early start of norepinephrine in septic shock. Crit. Care 2023, 27, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez, G.; Messina, A.; Kattan, E. Invasive arterial pressure monitoring: Much more than mean arterial pressure! Intensive Care Med. 2022, 48, 1495–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robba, C.; Wong, A.; Poole, D.; Al Tayar, A.; Arntfield, R.T.; Chew, M.S.; Corradi, F.; Douflé, G.; Goffi, A.; Lamperti, M.; et al. Basic ultrasound head-to-toe skills for intensivists in the general and neuro intensive care unit population: Consensus and expert recommendations of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med. 2021, 47, 1347–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Backer, D.; Aissaoui, N.; Cecconi, M.; Chew, M.S.; Denault, A.; Hajjar, L.; Hernandez, G.; Messina, A.; Myatra, S.N.; Ostermann, M.; et al. How can assessing hemodynamics help to assess volume status? Intensive Care Med. 2022, 48, 1482–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legrand, M.; De Backer, D.; Dépret, F.; Ait-Oufella, H. Recruiting the microcirculation in septic shock. Ann. Intensive Care 2019, 9, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongkolpun, W.; Orbegozo, D.; Cordeiro, C.P.R.; Franco, C.J.C.S.; Vincent, J.-L.M.; Creteur, J. Alterations in Skin Blood Flow at the Fingertip Are Related to Mortality in Patients with Circulatory Shock. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 48, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Shen, F.; Teboul, J.-L.; Anguel, N.; Beurton, A.; Bezaz, N.; Richard, C.; Monnet, X. Cardiac dysfunction induced by weaning from mechanical ventilation: Incidence, risk factors, and effects of fluid removal. Crit. Care 2016, 20, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruste, M.; Sghaier, R.; Chesnel, D.; Didier, L.; Fellahi, J.L.; Jacquet-Lagrèze, M. Perfusion-based deresuscitation during continuous renal replacement therapy: A before-after pilot study (The early dry Cohort). J. Crit. Care 2022, 72, 154169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kattan, E.; Castro, R.; Miralles-Aguiar, F.; Hernández, G.; Rola, P. The emerging concept of fluid tolerance: A position paper. J. Crit. Care 2022, 71, 154070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenny, J.-E.S. Assessing Fluid Intolerance with Doppler Ultrasonography: A Physiological Framework. Med. Sci. 2022, 10, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Z.; Jiang, L.; Xi, X.; Jiang, Q.; Zhu, B.; Wang, M.; Xing, J.; Zhang, D. Prognostic value of extravascular lung water assessed with lung ultrasound score by chest sonography in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. BMC Pulm. Med. 2015, 15, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaubien-Souligny, W.; Rola, P.; Haycock, K.; Bouchard, J.; Lamarche, Y.; Spiegel, R.; Denault, A.Y. Quantifying systemic congestion with Point-Of-Care ultrasound: Development of the venous excess ultrasound grading system. Ultrasound J. 2020, 12, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jozwiak, M.; Teboul, J.-L.; Monnet, X. Extravascular lung water in critical care: Recent advances and clinical applications. Ann. Intensive Care 2015, 5, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berlin, D.A.; Bakker, J. Starling curves and central venous pressure. Crit. Care 2015, 19, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prager, R.; Argaiz, E.; Pratte, M.; Rola, P.; Arntfield, R.; Beaubien-Souligny, W.; Denault, A.Y.; Haycock, K.; Aguiar, F.M.; Bakker, J.; et al. Doppler identified venous congestion in septic shock: Protocol for an international, multi-centre prospective cohort study (Andromeda-VEXUS). BMJ Open 2023, 13, e074843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monnet, X.; Marik, P.E.; Teboul, J.-L. Prediction of fluid responsiveness: An update. Ann. Intensive Care 2016, 6, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messina, A.; Bakker, J.; Chew, M.; De Backer, D.; Hamzaoui, O.; Hernandez, G.; Myatra, S.N.; Monnet, X.; Ostermann, M.; Pinsky, M.; et al. Pathophysiology of fluid administration in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med. Exp. 2022, 10, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kattan, E.; The ANDROMEDA-SHOCK Investigators; Ospina-Tascón, G.A.; Teboul, J.-L.; Castro, R.; Cecconi, M.; Ferri, G.; Bakker, J.; Hernández, G. Systematic assessment of fluid responsiveness during early septic shock resuscitation: Secondary analysis of the ANDROMEDA-SHOCK trial. Crit. Care 2020, 24, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, J.-L.; Cecconi, M.; De Backer, D. The fluid challenge. Crit. Care 2020, 24, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biais, M.; de Courson, H.; Lanchon, R.; Pereira, B.; Bardonneau, G.; Griton, M.; Sesay, M.; Nouette-Gaulain, K. Mini-fluid Challenge of 100 ml of Crystalloid Predicts Fluid Responsiveness in the Operating Room. Anesthesiology 2017, 127, 450–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monnet, X.; Lai, C.; Teboul, J.-L. How I personalize fluid therapy in septic shock? Crit. Care Lond. Engl. 2023, 27, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monnet, X.; Shi, R.; Teboul, J.-L. Prediction of fluid responsiveness. What’s new? Ann. Intensive Care 2022, 12, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monnet, X.; Teboul, J.-L. Passive leg raising: Five rules, not a drop of fluid! Crit. Care 2015, 19, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messina, A.; Montagnini, C.; Cammarota, G.; De Rosa, S.; Giuliani, F.; Muratore, L.; Della Corte, F.; Navalesi, P.; Cecconi, M. Tidal volume challenge to predict fluid responsiveness in the operating room: An observational study. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 2019, 36, 583–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vignon, P.; Repessé, X.; Bégot, E.; Léger, J.; Jacob, C.; Bouferrache, K.; Slama, M.; Prat, G.; Vieillard-Baron, A. Comparison of Echocardiographic Indices Used to Predict Fluid Responsiveness in Venti-lated Patients. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2017, 195, 1022–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virág, M.; Leiner, T.; Rottler, M.; Ocskay, K.; Molnar, Z. Individualized Hemodynamic Management in Sepsis. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gidwani, H.; Gómez, H. The crashing patient: Hemodynamic collapse. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 2017, 23, 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshimoto, H.; Fukui, S.; Higashio, K.; Endo, A.; Takasu, A.; Yamakawa, K. Optimal target blood pressure in critically ill adult patients with vasodilatory shock: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 962670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamzaoui, O.; Teboul, J.-L. Central venous pressure (CVP). Intensive Care Med. 2022, 48, 1498–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ospina-Tascón, G.A.; Teboul, J.-L.; Hernandez, G.; Alvarez, I.; Sánchez-Ortiz, A.I.; Calderón-Tapia, L.E.; Manzano-Nunez, R.; Quiñones, E.; Madriñan-Navia, H.J.; Ruiz, J.E.; et al. Diastolic shock index and clinical outcomes in patients with septic shock. Ann. Intensive Care 2020, 10, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamzaoui, O.; Teboul, J.-L. Importance of diastolic arterial pressure in septic shock: PRO. J. Crit. Care 2019, 51, 238–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlos Sanchez, E.; Pinsky, M.R.; Sinha, S.; Mishra, R.C.; Lopa, A.J.; Chatterjee, R. Fluids and Early Vasopressors in the Management of Septic Shock: Do We Have the Right Answers Yet? J. Crit. Care Med. Univ. Med. Si. Farm Din. Targu-Mures 2023, 9, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández, G.; Teboul, J.-L.; Bakker, J. Norepinephrine in septic shock. Intensive Care Med. 2019, 45, 687–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Álvarez, R.; Arboleda-Salazar, R. Vasopressin in Sepsis and Other Shock States: State of the Art. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, R.; Hamzaoui, O.; De Vita, N.; Monnet, X.; Teboul, J.-L. Vasopressors in septic shock: Which, when, and how much? Ann. Transl. Med. 2020, 8, 794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamzaoui, O.; Goury, A.; Teboul, J.-L. The Eight Unanswered and Answered Questions about the Use of Vasopressors in Septic Shock. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 4589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbouhy, M.A.; Soliman, M.; Gaber, A.; Taema, K.M.; Abdel-Aziz, A. Early Use of Norepinephrine Improves Survival in Septic Shock: Earlier than Early. Arch. Med. Res. 2019, 50, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudiger, A.; Singer, M. Decatecholaminisation during sepsis. Crit. Care 2016, 20, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerci, P.; Belveyre, T.; Mongardon, N.; Novy, E. When to start vasopressin in septic shock: The strategy we propose. Crit. Care 2022, 26, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, J.-L.; Pelosi, P.; Pearse, R.; Payen, D.; Perel, A.; Hoeft, A.; Romagnoli, S.; Ranieri, V.M.; Ichai, C.; Forget, P.; et al. Perioperative cardiovascular monitoring of high-risk patients: A consensus of 12. Crit. Care 2015, 19, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jozwiak, M.; Monnet, X.; Teboul, J.-L. Less or more hemodynamic monitoring in critically ill patients. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 2018, 24, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vincent, J.-L.; Rhodes, A.; Perel, A.; Martin, G.S.; Rocca, G.; Vallet, B.; Pinsky, M.R.; Hofer, C.K.; Teboul, J.-L.; de Boode, W.-P.; et al. Clinical review: Update on hemodynamic monitoring—A consensus of 16. Crit. Care 2011, 15, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecconi, M.; De Backer, D.; Antonelli, M.; Beale, R.; Bakker, J.; Hofer, C.; Jaeschke, R.; Mebazaa, A.; Pinsky, M.R.; Teboul, J.L.; et al. Consensus on circulatory shock and hemodynamic monitoring. Task force of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med. 2014, 40, 1795–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnar, Z.; Szabo, Z.; Nemeth, M. Multimodal individualized concept of hemodynamic monitoring. Curr. Opin. Anaesthesiol. 2017, 30, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavelli, F.; Teboul, J.L.; Monnet, X. How can CO2-derived indices guide resuscitation in critically ill patients? J. Thorac. Dis. 2019, 11 (Suppl. S11), S1528–S1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ait-Oufella, H.; Bige, N.; Boelle, P.Y.; Pichereau, C.; Alves, M.; Bertinchamp, R.; Baudel, J.L.; Galbois, A.; Maury, E.; Guidet, B. Capillary refill time exploration during septic shock. Intensive Care Med. 2014, 40, 958–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara, B.; Enberg, L.; Ortega, M.; Leon, P.; Kripper, C.; Aguilera, P.; Kattan, E.; Castro, R.; Bakker, J.; Hernandez, G. Capillary refill time during fluid resuscitation in patients with sepsis-related hyperlactatemia at the emergency department is related to mortality. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0188548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, G.; Ospina-Tascón, G.A.; Damiani, L.P.; Estenssoro, E.; Dubin, A.; Hurtado, J.; Friedman, G.; Castro, R.; Alegría, L.; Teboul, J.-L.; et al. Effect of a Resuscitation Strategy Targeting Peripheral Perfusion Status vs Serum Lactate Levels on 28-Day Mortality Among Patients with Septic Shock: The ANDROMEDA-SHOCK Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2019, 321, 654–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacquet-Lagrèze, M.; Bouhamri, N.; Portran, P.; Schweizer, R.; Baudin, F.; Lilot, M.; Fornier, W.; Fellahi, J.-L. Capillary refill time variation induced by passive leg raising predicts capillary refill time response to volume expansion. Crit. Care 2019, 23, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ince, C. Hemodynamic coherence and the rationale for monitoring the microcirculation. Crit. Care 2015, 19, S8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubin, A.; Pozo, M.O.; Casabella, C.A.; Pálizas, F.; Murias, G.; Moseinco, M.C.; Kanoore Edul, V.S.; Pálizas, F.; Estenssoro, E.; Ince, C. Increasing arterial blood pressure with norepinephrine does not improve microcir-culatory blood flow: A prospective study. Crit. Care 2009, 13, R92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilty, M.P.; Ince, C. Automated quantification of tissue red blood cell perfusion as a new resuscitation target. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 2020, 26, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bendavid, I.; Singer, P.; Theilla, M.; Themessl-Huber, M.; Sulz, I.; Mouhieddine, M.; Schuh, C.; Mora, B.; Hiesmayr, M. NutritionDay ICU: A 7 year worldwide prevalence study of nutrition practice in intensive care. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 36, 1122–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, K.-Y.; Chen, Y.-M.; Wang, C.-C.; Wang, Y.-H.; Lin, C.-Y.; Chang, Y.-T.; Huang, K.-T.; Lin, M.-C.; Fang, W.-F. Insufficient Nutrition and Mortality Risk in Septic Patients Admitted to ICU with a Focus on Immune Dysfunction. Nutrients 2019, 11, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wischmeyer, P.E. Nutrition Therapy in Sepsis. Crit. Care Clin. 2018, 34, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zusman, O.; Theilla, M.; Cohen, J.; Kagan, I.; Bendavid, I.; Singer, P. Resting energy expenditure, calorie and protein consumption in critically ill patients: A retrospective cohort study. Crit. Care 2016, 20, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preiser, J.C. High protein intake during the early phase of critical illness: Yes or no? Crit. Care 2018, 22, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyland, D.K.; Patel, J.; Compher, C.; Rice, T.W.; E Bear, D.; Lee, Z.-Y.; González, V.C.; O’Reilly, K.; Regala, R.; Wedemire, C.; et al. The effect of higher protein dosing in critically ill patients with high nutritional risk (EFFORT Protein): An international, multicentre, pragmatic, registry-based randomised trial. Lancet 2023, 401, 568–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancl, E.E.; Muzevich, K.M. Tolerability and safety of enteral nutrition in critically Ill patients receiving intravenous vasopressor therapy. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2013, 37, 641–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, S.R.; Schofield-Robinson, O.J.; Alderson, P.; Smith, A.F. Enteral versus parenteral nutrition and enteral versus a combination of enteral and parenteral nutrition for adults in the intensive care unit. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 6, CD012276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, F.; Heighes, P.T.; Allingstrup, M.J.; Doig, G.S. Early Enteral Nutrition Provided Within 24 Hours of ICU Admission: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 46, 1049–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reignier, J.; Boisramé-Helms, J.; Brisard, L.; Lascarrou, J.B.; Ait Hssain, A.; Anguel, N.; Argaud, L.; Asehnoune, K.; Asfar, P.; Bellec, F. Enteral versus parenteral early nutrition in ventilated adults with shock: A randomised, controlled, multicentre, open-label, parallel-group study (NUTRIREA-2). Lancet 2018, 391, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaser, A.R.; ESICM Working Group on Gastrointestinal Function; Starkopf, J.; Alhazzani, W.; Berger, M.M.; Casaer, M.P.; Deane, A.M.; Fruhwald, S.; Hiesmayr, M.; Ichai, C.; et al. Early enteral nutrition in critically ill patients: ESICM clinical practice guidelines. Intensive Care Med. 2017, 43, 380–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierre, J.F.; Heneghan, A.F.; Lawson, C.M.; Wischmeyer, P.E.; Kozar, R.A.; Kudsk, K.A. Pharmaconutrition review: Physiological mechanisms. JPEN J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2013, 37, 51S–65S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langlois, P.L.; D’Aragon, F.; Hardy, G.; Manzanares, W. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in critically ill patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrition 2019, 61, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Jativa, D.F. Vitamin C supplementation in the critically ill: A systematic review and meta-analysis. SAGE Open Med. 2018, 6, 2050312118807615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singer, P.; Blaser, A.R.; Berger, M.M.; Alhazzani, W.; Calder, P.C.; Casaer, M.P.; Hiesmayr, M.; Mayer, K.; Montejo, J.C.; Pichard, C.; et al. ESPEN guideline on clinical nutrition in the intensive care unit. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 38, 48–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baptista, G.; Barazzoni, R.; Blaauw, R.; Coats, A.; Crivelli, A.; Evans, D.; Gramlich, L.; Fuchs-Tarlovsky, V.; Keller, H.; Llido, L.; et al. GLIM criteria for the diagnosis of malnutrition—A consensus report from the global clinical nutrition community. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 38, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, F.; Liberale, L.; Preda, A.; Schindler, T.H.; Montecucco, F. Septic Cardiomyopathy: From Pathophysiology to the Clinical Setting. Cells 2022, 11, 2833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravikumar, N.; Sayed, M.A.; Poonsuph, C.J.; Sehgal, R.; Shirke, M.M.; Harky, A. Septic cardiomyopathy: From basics to management choices. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 2021, 46, 100767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, R.; Kuriyama, A.; Takada, T.; Nasu, M. Prevalence and risk factors of sepsis-induced cardiomyopathy: A retrospective cohort study. Medicine 2016, 44, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvin, J.E.; Driedger, A.A.; Sibbald, W.J. An assessment of myocardial function in human sepsis utilizing ECG gated cardiac scintigraphy. Chest 1981, 80, 579–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berrios, R.A.S.; O’horo, J.C.; Velagapudi, V.; Pulido, J.N. Correlation of left ventricular systolic dysfunction determined by low ejection fraction and 30-day mortality in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Crit. Care 2014, 29, 495–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalla, K.; Hallman, C.; Bech-Hanssen, O.; Haney, M.; Ricksten, S.E. Strain echocardiography identifies impaired longitudinal systolic function in pa-tients with septic shock and preserved ejection fraction. Cardiovasc. Ultrasound 2015, 13, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havaldar, A.A. Evaluation of sepsis induced cardiac dysfunction as a predictor of mortality. Cardiovasc. Ultrasound 2018, 16, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanfilippo, F.; Corredor, C.; Fletcher, N.; Landesberg, G.; Benedetto, U.; Foex, P.; Cecconi, M. Diastolic dysfunction and mortality in septic patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2015, 41, 1004–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagueh, S.F.; Smiseth, O.A.; Appleton, C.P.; Byrd, B.F.; Dokainish, H.; Edvardsen, T.; Flachskampf, F.A.; Gillebert, T.C.; Klein, A.L.; Lancellotti, P. Recommendations for the evaluation of left ventricular diastolic function by echocardiography: An update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur. J. Echocardiogr. 2016, 17, 1321–1360. [Google Scholar]

- Lanspa, M.J.; Gutsche, A.R.; Wilson, E.L.; Olsen, T.D.; Hirshberg, E.L.; Knox, D.B.; Brown, S.M.; Grissom, C.K. Application of a simplified definition of diastolic function in severe sepsis and septic shock. Crit. Care 2016, 20, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanspa, M.J.; Olsen, T.D.; Wilson, E.L.; Leguyader, M.L.; Hirshberg, E.L.; Anderson, J.L.; Brown, S.M.; Grissom, C.K. A simplified definition of diastolic function in sepsis, compared against standard definitions. J. Intensive Care 2019, 7, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allyn, J.; Allou, N.; Dib, M.; Tashk, P.; Desmard, M.; Dufour, G.; Daoud, O.; Mentec, H.; Montravers, P. Echocardiography to predict tolerance to negative fluid balance in acute respiratory distress syndrome/acute lung injury. J. Crit. Care 2013, 28, 1006–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez Hernández, R.; Ramasco Rueda, F. Biomarkers as Prognostic Predictors and Therapeutic Guide in Critically Ill Patients: Clinical Evidence. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallabhajosyula, S.; Wang, Z.; Murad, M.H.; Vallabhajosyula, S.; Sundaragiri, P.R.; Kashani, K.; Miller, W.L.; Jaffe, A.S.; Vallabhajosyula, S. Natriuretic Peptides to Predict Short-Term Mortality in Patients with Sepsis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Mayo Clin. Proc. Innov. Qual. Outcomes 2020, 4, 50–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morelli, A.; De Castro, S.; Teboul, J.-L.; Singer, M.; Rocco, M.; Conti, G.; De Luca, L.; Di Angelantonio, E.; Orecchioni, A.; Pandian, N.G.; et al. Effects of levosimendan on systemic and regional hemodynamics in septic myocardial depression. Intensive Care Med. 2005, 31, 638–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, J.-I.; Hu, M.-H.; Lai, Z.-Z.; Ji, C.-L.; Xu, X.-J.; Zhang, G.; Tian, S. levosimendan versus dobutamine in myocardial injury patients with septic shock: A randomized controlled trial. Med. Sci. Monit. Int. Med. J. Exp. Clin. Res. 2016, 22, 1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, T.; Zhang, N.; Cui, N.; Wang, S.-H.; Ding, X.-X.; Li, N.; Chen, N.; Yu, Z.-B. Efficacy of Levosimendan in the Treatment of Patients with Severe Septic Cardiomyopathy. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesthesia 2023, 37, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, A.C.; Perkins, G.D.; Singer, M.; McAuley, D.F.; Orme, R.M.; Santhakumaran, S.; Mason, A.J.; Cross, M.; Al-Beidh, F.; Best-Lane, J.; et al. Levosimendan for the prevention of acute organ dysfunction in sepsis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 1638–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharjee, S.; Soni, K.D.; Maitra, S.; Baidya, D.K. Levosimendan does not provide mortality benefit over dobutamine in adult patients with septic shock: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Clin. Anesthesia 2017, 39, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beidh, F.; Best-Lane, J.; Brealey, D.; Nutt, C.; McNamee, J.J.; Reschreiter, H.; Breen, A.; Liu, K.D.; Ashby, D. Levosimendan for the Prevention of Acute Organ Dysfunction in Sepsis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 1638–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girardis, M.; Bettex, D.; Bojan, M.; Demponeras, C.; Fruhwald, S.; Gál, J.; Groesdonk, H.V.; Guarracino, F.; Guerrero-Orriach, J.L.; Heringlake, M.; et al. Levosimendan in intensive care and emergency medicine: Literature update and expert recommendations for optimal efficacy and safety. J. Anesth. Analg. Crit. Care 2022, 2, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faris, J.G.; Veltman, M.G.; Royse, C.F. Limited transthoracic echocardiography assessment in anaesthesia and critical care. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Anaesthesiol. 2009, 23, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perera, P.; Mailhot, T.; Riley, D.; Mandavia, D. The RUSH Exam: Rapid Ultrasound in SHock in the Evaluation of the Critically lll. Emerg. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2010, 28, 29–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, T.; Yoshida, T.; Noma, H.; Nomura, T.; Suzuki, A.; Mihara, T. Diagnostic accuracy of point-of-care ultrasound for shock: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Care 2023, 27, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercadal, J.; Borrat, X.; Hernández, A.; Denault, A.; Beaubien-Souligny, W.; González-Delgado, D.; Vives, M.; Carmona, P.; Nagore, D.; Sánchez, E.; et al. A simple algorithm for differential diagnosis in hemodynamic shock based on left ventricle outflow tract velocity–time integral measurement: A case series. Ultrasound J. 2022, 14, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geri, G.; Vignon, P.; Aubry, A.; Fedou, A.-L.; Charron, C.; Silva, S.; Repessé, X.; Vieillard-Baron, A. Cardiovascular clusters in septic shock combining clinical and echocardiographic parameters: A post hoc analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2019, 45, 657–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, J.H.; Forbes, J.; Nakada, T.-A.; Walley, K.R.; Russell, J.A. Fluid resuscitation in septic shock: A positive fluid balance and elevated central venous pressure are associated with increased mortality. Crit. Care Med. 2011, 39, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viana-Rojas, J.A.; Argaiz, E.; Robles-Ledesma, M.; Arias-Mendoza, A.; Nájera-Rojas, N.A.; Alonso-Bringas, A.P.; Ríos-Arce, L.F.D.L.; Armenta-Rodriguez, J.; Gopar-Nieto, R.; la Cruz, J.L.B.-D.; et al. Venous excess ultrasound score and acute kidney injury in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Eur. Heart J. Acute Cardiovasc. Care 2023, 12, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrei, S.; Bahr, P.-A.; Nguyen, M.; Bouhemad, B.; Guinot, P.-G. Prevalence of systemic venous congestion assessed by Venous Excess Ultrasound Grading System (VExUS) and association with acute kidney injury in a general ICU cohort: A prospective multicentric study. Crit. Care 2023, 27, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, M.; Viana, E.; Martins, J.D.; da Silva, R.C. Evaluation of Congestion Levels in Septic Patients Admitted to Critical Care Units with a Combined Venous Excess-Lung Ultrasound Score (VExLUS)—A Research Protocol. POCUS J. 2023, 8, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellman, T.; Uusalo, P.; Järvisalo, M.J. Renal Replacement Techniques in Septic Shock. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronco, C.; Bellomo, R. Hemoperfusion: Technical aspects and state of the art. Crit. Care 2022, 26, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berlot, G.; Tomasini, A.; Zanchi, S.; Moro, E. The Techniques of Blood Purification in the Treatment of Sepsis and Other Hyperinflammatory Conditions. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mensa, J.; Barberán, J.; Ferrer, R.; Borges, M.; Rascado, P.; Maseda, E.; Oliver, A.; Marco, F.; Adalia, R.; Aguilar, G.; et al. Recommendations for antibiotic selection for severe nosocomial infections. Rev Esp. Quim. Publ. Soc Esp. Quim. 2021, 34, 511–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, Y.; Paul, R.; Ansari, A.S.; Banerjee, T.; Gunaydin, S.; Nassiri, A.A.; Pappalardo, F.; Premužić, V.; Sathe, P.; Singh, V.; et al. Extracorporeal blood purification strategies in sepsis and septic shock: An insight into recent advancements. World J. Crit. Care Med. 2023, 12, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronco, C.; Chawla, L.; Husain-Syed, F.; Kellum, J.A. Rationale for sequential extracorporeal therapy (SET) in sepsis. Crit. Care 2023, 27, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Rodriguez, J.C.; Plata-Menchaca, E.P.; Chiscano-Camón, L.; Ruiz-Sanmartin, A.; Pérez-Carrasco, M.; Palmada, C.; Ribas, V.; Martínez-Gallo, M.; Hernández-González, M.; Gonzalez-Lopez, J.J.; et al. Precision medicine in sepsis and septic shock: From omics to clinical tools. World J. Crit. Care Med. 2022, 11, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angus, D.C. Drotrecogin alfa (activated)... a sad final fizzle to a roller-coaster party. Crit. Care 2012, 16, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A. An alternate pathophysiologic paradigm of sepsis and septic shock: Implications for optimizing antimicrobial therapy. Virulence 2014, 5, 80–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monard, C.; Rimmelé, T.; Ronco, C. Extracorporeal Blood Purification Therapies for Sepsis. Blood Purif. 2019, 47, 2–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virzì, G.M.; Mattiotti, M.; de Cal, M.; Ronco, C.; Zanella, M.; De Rosa, S. Endotoxin in Sepsis: Methods for LPS Detection and the Use of Omics Techniques. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angus, D.C.; van der Poll, T. Severe sepsis and septic shock. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 840–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Neill, L.A.J.; Golenbock, D.; Bowie, A.G. The history of Toll-like receptors—Redefining innate immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2013, 13, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimaldi, D.; Vincent, J.-L. Clinical trial research in focus: Rethinking trials in sepsis. Lancet Respir. Med. 2017, 5, 610–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricci, Z.; Romagnoli, S.; Reis, T.; Bellomo, R.; Ronco, C. Hemoperfusion in the intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med. 2022, 48, 1397–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honore, P.M.; Hoste, E.; Molnár, Z.; Jacobs, R.; Joannes-Boyau, O.; Malbrain, M.L.N.G.; Forni, L.G. Cytokine removal in human septic shock: Where are we and where are we going? Ann. Intensive Care 2019, 9, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavaillon, J.M.; Munoz, C.; Fitting, C.; Misset, B.; Carlet, J. Circulating cytokines: The tip of the iceberg? Circ. Shock 1992, 38, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ronco, C.; Bellomo, R.; Homel, P.; Brendolan, A.; Dan, M.; Piccinni, P.; La Greca, G. Effects of different doses in continuous veno-venous haemofiltration on outcomes of acute renal failure: A prospective randomised trial. Lancet 2000, 356, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joannes-Boyau, O.; Honoré, P.M.; Perez, P.; Bagshaw, S.M.; Grand, H.; Canivet, J.-L.; Dewitte, A.; Flamens, C.; Pujol, W.; Grandoulier, A.-S.; et al. High-volume versus standard-volume haemofiltration for septic shock patients with acute kidney injury (IVOIRE study): A multicentre randomized controlled trial. Intensive Care Med. 2013, 39, 1535–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Kelly, Y.P.; Palevsky, P.M.; Waikar, S.S. Intensity of Renal Replacement Therapy and Duration of Mechanical Ventilation. Chest 2020, 158, 1473–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Feng, Y.; Fu, P. Blood purification for sepsis: An overview. Precis. Clin. Med. 2021, 4, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romaschin, A.D.; Harris, D.M.; Ribeiro, M.B.; Paice, J.; Foster, D.M.; Walker, P.M.; Marshall, J.C. A rapid assay of endotoxin in whole blood using autologous neutrophil de-pendent chemiluminescence. J. Immunol. Methods 1998, 212, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romaschin, A.D.; Klein, D.J.; Marshall, J.C. Bench-to-bedside review: Clinical experience with the endotoxin activity assay. Crit. Care 2012, 16, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikeda, T.; Kamohara, H.; Suda, S.; Nagura, T.; Tomino, M.; Sugi, M.; Wajima, Z. Comparative Evaluation of Endotoxin Activity Level and Various Biomarkers for Infection and Outcome of ICU-Admitted Patients. Biomedicines 2019, 7, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, J.C.; Foster, D.; Vincent, J.; Cook, D.J.; Cohen, J.; Dellinger, R.P.; Opal, S.; Abraham, E.; Brett, S.J.; Smith, T.; et al. Diagnostic and Prognostic implications of endotoxemia in critical illness: Results of the MEDIC study. J. Infect. Dis. 2004, 190, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, B.; White, J.C.; Nylén, E.S.; Snider, R.H.; Becker, K.L.; Habener, J.F. Ubiquitous expression of the Calcitonin-I Gene in multiple tissues in response to sepsis. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2001, 86, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leli, C.; Ferranti, M.; Moretti, A.; Al Dhahab, Z.S.; Cenci, E.; Mencacci, A. Procalcitonin Levels in Gram-Positive, Gram-Negative, and Fungal Bloodstream Infections. Dis. Markers 2015, 2015, e701480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McElvaney, O.J.; Curley, G.F.; Rose-John, S.; McElvaney, N.G. Interleukin-6: Obstacles to targeting a complex cytokine in critical illness. Lancet Respir. Med. 2021, 9, 643–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoji, H.; Tani, T.; Hanasawa, K.; Kodama, M. Extracorporeal endotoxin removal by polymyxin b immobilized fiber cartridge: Designing and antiendotoxin efficacy in the clinical application. Ther. Apher. 1998, 2, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoji, H.; Opal, S.M. Therapeutic Rationale for Endotoxin Removal with Polymyxin B Immobilized Fiber Column (PMX) for Septic Shock. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, J.L.; Laterre, P.-F.; Cohen, J.; Burchardi, H.; Bruining, H.; Lerma, F.A.; Wittebole, X.; De Backer, D.; Brett, S.; Marzo, D.; et al. A Pilot-controlled study of a polymyxin B-immobilized hemoperfusion cartridge in patients with severe sepsis secondary to intra-abdominal infection. Shock 2005, 23, 400–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz, D.N.; A Perazella, M.; Bellomo, R.; de Cal, M.; Polanco, N.; Corradi, V.; Lentini, P.; Nalesso, F.; Ueno, T.; Ranieri, V.M.; et al. Effectiveness of polymyxin B-immobilized fiber column in sepsis: A systematic review. Crit. Care 2007, 11, R47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz, D.N.; Antonelli, M.; Fumagalli, R.; Foltran, F.; Brienza, N.; Donati, A.; Malcangi, V.; Petrini, F.; Volta, G.; Bobbio Pallavicini, F.M.; et al. Early use of polymyxin B hemoperfusion in abdominal septic shock: The EUPHAS randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2009, 301, 2445–2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Payen, D.M.; The ABDOMIX Group; Guilhot, J.; Launey, Y.; Lukaszewicz, A.C.; Kaaki, M.; Veber, B.; Pottecher, J.; Joannes-Boyau, O.; Martin-Lefevre, L.; et al. Early use of polymyxin B hemoperfusion in patients with septic shock due to peritonitis: A multicenter randomized control trial. Intensive Care Med. 2015, 41, 975–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dellinger, R.P.; Bagshaw, S.M.; Antonelli, M.; Foster, D.M.; Klein, D.J.; Marshall, J.C.; Palevsky, P.M.; Weisberg, L.S.; Schorr, C.A.; Trzeciak, S.; et al. Effect of Targeted Polymyxin B Hemoperfusion on 28-Day Mortality in Patients with Septic Shock and Elevated Endotoxin Level: The EUPHRATES Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2018, 320, 1455–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, D.J.; Foster, D.; Walker, P.M.; Bagshaw, S.M.; Mekonnen, H.; Antonelli, M. Polymyxin B hemoperfusion in endotoxemic septic shock patients without extreme endotoxemia: A post hoc analysis of the EUPHRATES trial. Intensive Care Med. 2018, 44, 2205–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoji, H.; Ferrer, R. Potential survival benefit and early recovery from organ dysfunction with polymyxin B hemoperfusion: Perspectives from a real-world big data analysis and the supporting mechanisms of action. J. Anesthesia Analg. Crit. Care 2022, 2, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, C.; Mao, Z.; Qi, S.; Song, R.; Zhou, F. Effectiveness of polymyxin B-immobilized hemoperfusion against sepsis and septic shock: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Crit. Care 2021, 63, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulabukhov, V.V. Use of an endotoxin adsorber in the treatment of severe abdominal sepsis. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 2008, 52, 1024–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ala-Kokko, T.; Laurila, J.; Koskenkari, J. A new endotoxin adsorber in septic shock: Observational case series. Blood Purif. 2011, 32, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaroustovsky, M.; Abramyan, M.; Popok, Z.; Nazarova, E.; Stupchenko, O.; Popov, D.; Plushch, M.; Samsonova, N. Preliminary Report regarding the Use of Selective Sorbents in Complex Cardiac Surgery Patients with Extensive Sepsis and Prolonged Intensive Care Stay. Blood Purif. 2009, 28, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipcsey, M.; Tenhunen, J.; Pischke, S.E.; Kuitunen, A.; Flaatten, H.; De Geer, L.; Sjölin, J.; Frithiof, R.; Chew, M.S.; Bendel, S.; et al. Endotoxin Removal in Septic Shock with the Alteco LPS Adsorber Was Safe but Showed no Benefit Compared to Placebo in the Double-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial—The Asset Study. Shock 2020, 54, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seffer, M.-T.; Cottam, D.; Forni, L.G.; Kielstein, J.T. Heparin 2.0: A New Approach to the Infection Crisis. Blood Purif. 2021, 50, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Rodríguez, J.C.; Molnar, Z.; Deliargyris, E.N.; Ferrer, R. The Use of CytoSorb Therapy in Critically Ill COVID-19 Patients: Review of the Rationale and Current Clinical Experiences. Crit. Care Res. Pr. 2021, 2021, 7769516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Morán, F.; Mateu-Campos, M.L.; Bernal-Julián, F.; Gil-Santana, A.; Sánchez-Herrero, A.; Martínez-Gaspar, T. Haemoadsorption Combined with Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy in Abdominal Sepsis: Case Report Series. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecchi, M.; Ulsamer, A.; Villa, G. Oxiris Membrane in Sepsis and Multiple Organ Failure. Contrib. Nephrol. 2023, 200, 55–65. [Google Scholar]

- Verresen, L.; Fink, E.; Lemke, H.-D.; Vanrenterghem, Y. Bradykinin is a mediator of anaphylactoid reactions during hemodialysis with AN69 membranes. Kidney Int. 1994, 45, 1497–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rimmelé, T.; Assadi, A.; Cattenoz, M.; Desebbe, O.; Lambert, C.; Boselli, E.; Goudable, J.; Étienne, J.; Chassard, D.; Bricca, G.; et al. High-volume haemofiltration with a new haemofiltration membrane having enhanced adsorption properties in septic pigs. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2009, 24, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malard, B.; Lambert, C.; Kellum, J.A. In vitro comparison of the adsorption of inflammatory mediators by blood purification devices. Intensive Care Med. Exp. 2018, 6, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romaschin, A.D.; Obiezu-Forster, C.V.; Shoji, H.; Klein, D.J. Novel Insights into the Direct Removal of Endotoxin by Polymyxin B Hemoperfusion. Blood Purif. 2017, 44, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Sun, P.; Chang, K.; Yang, M.; Deng, N.; Chen, S.; Su, B. Effect of Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy with the oXiris Hemofilter on Critically Ill Patients: A Narrative Review. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broman, M.E.; Hansson, F.; Vincent, J.-L.; Bodelsson, M. Endotoxin and cytokine reducing properties of the oXiris membrane in patients with septic shock: A randomized crossover double-blind study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0220444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwindenhammer, V.; Girardot, T.; Chaulier, K.; Grégoire, A.; Monard, C.; Huriaux, L.; Illinger, J.; Leray, V.; Uberti, T.; Crozon-Clauzel, J.; et al. oXiris® Use in Septic Shock: Experience of Two French Centres. Blood Purif. 2019, 47, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turani, F.; Barchetta, R.; Falco, M.; Busatti, S.; Weltert, L. Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy with the Adsorbing Filter oXiris in Septic Patients: A Case Series. Blood Purif. 2019, 47, 54–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, J.; Xiao, W.; Lin, J. Effect of oXiris-CVVH on the Clinical Outcomes of Patients with Septic Shock: An Inverse Probability of Treatment-Weighted Analysis. Blood Purif. 2022, 51, 972–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, M.; Wang, H.; Tang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, F.; Zhang, L.; Fu, P. Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy with Adsorbing Filter oXiris in Acute Kidney Injury With Septic Shock: A Retrospective Observational Study. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 789623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, G.; Romagnoli, S.; De Rosa, S.; Greco, M.; Resta, M.; Montin, D.P.; Prato, F.; Patera, F.; Ferrari, F.; Rotondo, G.; et al. Blood purification therapy with a hemodiafilter featuring enhanced adsorptive properties for cytokine removal in patients presenting COVID-19: A pilot study. Crit. Care 2020, 24, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Arab, O.; Huette, P.; Haye, G.; Guilbart, M.; Touati, G.; Diouf, M. Effect of the oXiris membrane on microcirculation after cardiac surgery under cardi-opulmonary bypass: Study protocol for a randomised controlled trial (OXICARD Study). BMJ Open 2021, 11, e044424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin, L.; Charbel, R.; Cousin, V.L.; Marais, C.; Claude, C.; Barreault, S.; Durand, P.; Miatello, J.; Tissières, P. Blood Purification with oXiris© in Critically Ill Children with Vasoplegic Shock. Blood Purif. 2023, 52, 541–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wei, S.-R.; Ding, T.; Zhang, L.-P.; Weng, Z.-H.; Cheng, M.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, M.; Liu, F.-J.; Yan, B.-B.; et al. Continuous renal replacement therapy with oXiris® in patients with hematologically malignant septic shock: A retrospective study. World J. Clin. Cases 2023, 11, 6073–6082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, Y.; Pan, J.; Zhang, C. The application value of oXiris-endotoxin adsorption in sepsis. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2021, 13, 3839–3844. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Cove, M.; Nguyen, B.G.; Lumlertgul, N.; Ganesh, K.; Chan, A.; Bui, G.T.H.; Guo, C.; Li, J.; Liu, S.; et al. Adsorptive hemofiltration for sepsis management: Expert recommendations based on the Asia Pacific experience. Chin. Med. J. 2021, 134, 2258–2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pickkers, P.; Vassiliou, T.; Liguts, V.; Prato, F.; Tissieres, P.; Kloesel, S.; Turani, F.; Popevski, D.; Broman, M.; Gindac, C.M.; et al. Sepsis Management with a Blood Purification Membrane: European Experience. Blood Purif. 2019, 47, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Hernández, R.; Espigares-López, M.; Miralles-Aguiar, F.; Gámiz-Sánchez, R.; Fernández, F.A.; Romero, A.P.; Torres, L.; Seoane, E.C. Immunomodulation using CONVEHY® for COVID-19: From the storm to the cytokine anticyclone. Rev. Esp. Anestesiol. Reanim. 2021, 68, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maynar Moliner, J.; Honore, P.M.; Sánchez-Izquierdo Riera, J.A.; Herrera Gutiérrez, M.; Spapen, H.D. Handling continuous renal replacement therapy-related adverse effects in intensive care unit patients: The dialytrauma concept. Blood Purif. 2012, 34, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; He, Y.; Guo, Q.; Zhao, Y.; He, J.; Chen, Y.; Chen, W.; Zhou, Y.; Peng, Z.; Deng, K.; et al. Continuous renal replacement therapy with the adsorptive oXiris filter may be associated with the lower 28-day mortality in sepsis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Care 2023, 27, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novelli, G.; Ferretti, G.; Ruberto, F.; Morabito, V.; Pugliese, F. Early management of endotoxemia using the endotoxin activity assay and polymyxin B-based hemoperfusion. Contrib. Nephrol. 2010, 167, 91–101. [Google Scholar]

- Novelli, G.; Ferretti, G.; Poli, L.; Pretagostini, R.; Ruberto, F.; Perrella, S.; Levi, S.; Morabito, V.; Berloco, P. Clinical results of treatment of postsurgical endotoxin-mediated sepsis with Polymyxin-B direct hemoperfusion. Transplant. Proc. 2010, 42, 1021–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwagami, M.; Yasunaga, H.; Noiri, E.; Horiguchi, H.; Fushimi, K.; Matsubara, T.; Yahagi, N.; Nangaku, M.; Doi, K. Potential Survival Benefit of Polymyxin B Hemoperfusion in Septic Shock Patients on Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy: A Propensity-Matched Analysis. Blood Purif. 2016, 42, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forni, L.G. Blood Purification Studies in the ICU: What Endpoints Should We Use? Blood Purif. 2022, 51, 990–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Rodríguez, J.C.; Plata-Menchaca, E.P.; Chiscano-Camón, L.; Ruiz-Sanmartin, A.; Ferrer, R. Blood purification in sepsis and COVID-19: What’s new in cytokine and endotoxin hemoadsorption. J. Anesth. Analg. Crit. Care 2022, 2, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamath, S.; Hammad Altaq, H.; Abdo, T. Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock: What Have We Learned in the Last Two Decades? Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Phenotype (% of Subjects in the Sample) | Phenotype Features | Ultrasound and Hemodynamic Findings | Diagnostic Performance | Mortality | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster 1 Well-resuscitated (16.9%) | Normal systolic function of both ventricles Nonfluid responsiveness | Normal TEE | 7 days: 9.8% ICU: 21.3% | ||

| Cluster 2 LV Systolic dysfunction (17.7%) | Decreased LVEF and LVFAC Low CO High lactate and high doses of noradrenaline Nonfluid responsiveness | LVEF < 40% Aortic VTI < 14 cm LVFAC < 33% | Sensitivity: 54.7%% Specificity: 97.6% PPV: 83.3%% NPV: 90.9%% AUC: 0.959 | 7 days: 32.8% ICU: 50% | 14% of patients had LVEF > 45% ScVO2 normal E/e’ normal |

| Cluster 3 Hyperkinetic state (23.3%) | Elevated LVEF High CO Nonfluid responsiveness | Aortic VTI > 20 cm HR: < 106 LPM LVFAC > 56% | Sensitivity: 17.9%% Specificity: 98.2%% VPP: 75%% NPV: 79.7%% AUC: 0.885 | 7 days: 8.3% ICU: 23.8% | |

| Cluster 4 RV failure (22.5%) | High RV/LV EDA LVEF normal or supranormal Nonfluid responsiveness | RV/LV EDA > 0.8 SAP < 100 mmHg DAP < 51 mmHg | Sensitivity: 29.6%% Specificity: 98.9%% PPV: 88.9%% NPV: 82.9%% AUC: 0.951 | 7 days: 27.2% ICU: 42% | Increased number of patients with PaO2/FiO2 < 200 mmHg |

| Cluster 5 Still hypovolemic (19.4%) | Low CO Elevated LVEF Fluid responsiveness | Aortic VTI < 16 cm E wave < 67 cm/s ∆SVC > 39% | Sensitivity: 25.7%% Specificity: 99.3%% VPP: 90%% NPV: 84.7%% AUC: 0.955 | 7 days: 23.2% ICU: 38.6% | These patients had received more volume in the initial stages of resuscitation compared to the other phenotypes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ramasco, F.; Nieves-Alonso, J.; García-Villabona, E.; Vallejo, C.; Kattan, E.; Méndez, R. Challenges in Septic Shock: From New Hemodynamics to Blood Purification Therapies. J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, 176. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm14020176

Ramasco F, Nieves-Alonso J, García-Villabona E, Vallejo C, Kattan E, Méndez R. Challenges in Septic Shock: From New Hemodynamics to Blood Purification Therapies. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2024; 14(2):176. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm14020176

Chicago/Turabian StyleRamasco, Fernando, Jesús Nieves-Alonso, Esther García-Villabona, Carmen Vallejo, Eduardo Kattan, and Rosa Méndez. 2024. "Challenges in Septic Shock: From New Hemodynamics to Blood Purification Therapies" Journal of Personalized Medicine 14, no. 2: 176. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm14020176

APA StyleRamasco, F., Nieves-Alonso, J., García-Villabona, E., Vallejo, C., Kattan, E., & Méndez, R. (2024). Challenges in Septic Shock: From New Hemodynamics to Blood Purification Therapies. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 14(2), 176. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm14020176