Healthcare Utilization and Costs after Receiving a Positive BRCA1/2 Result from a Genomic Screening Program

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

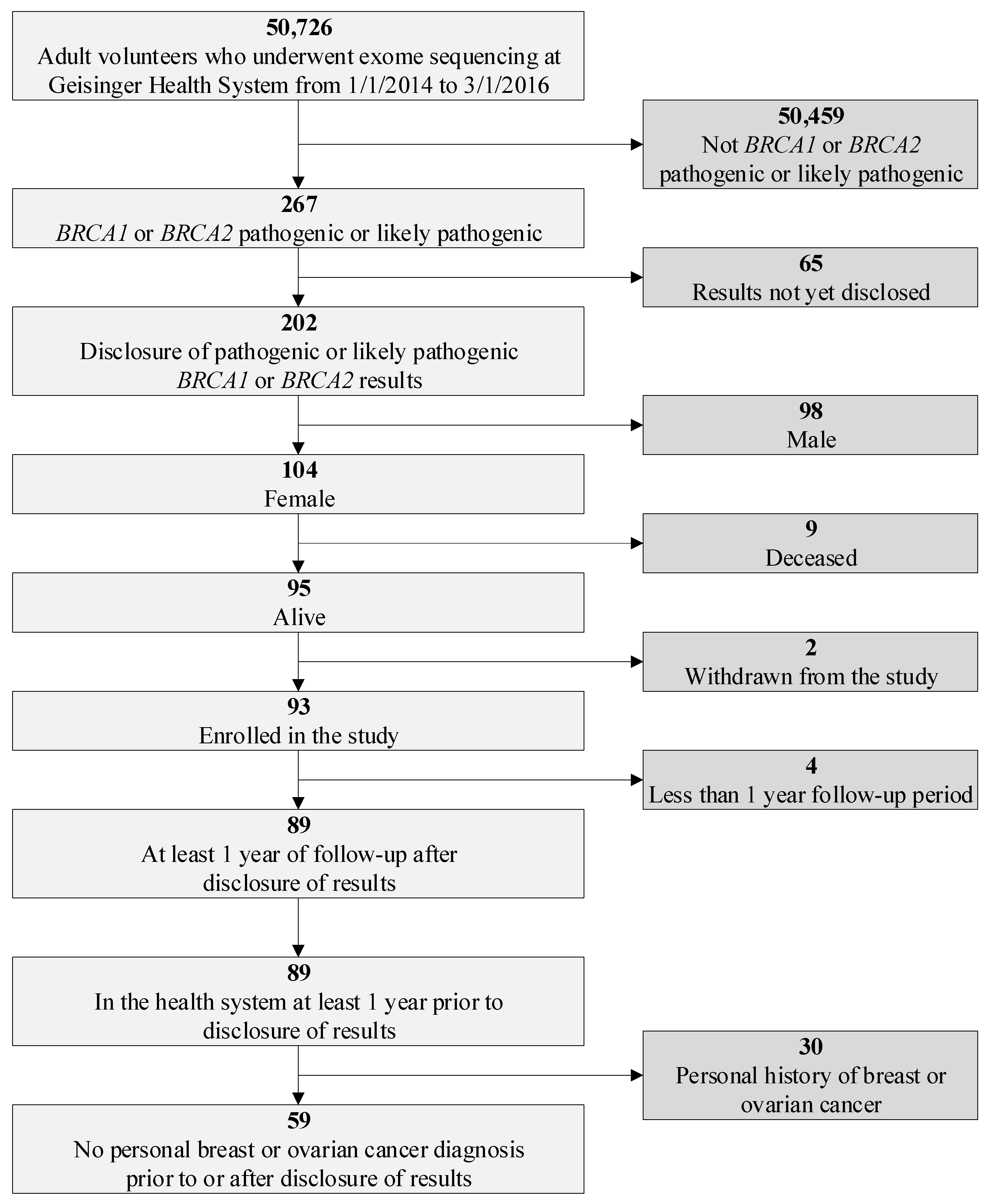

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Data

2.3. Study Design

2.3.1. Healthcare Utilization and Costs

2.3.2. Uptake of Guidelines-Recommended Risk Management

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

3.2. Healthcare Utilization

3.3. Costs

3.4. Uptake of Guidelines-Recommended Risk Management

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Manickam, K.; Buchanan, A.H.; Schwartz, M.L.B.; Hallquist, M.L.G.; Williams, J.L.; Rahm, A.K.; Rocha, H.; Savatt, J.M.; Evans, A.E.; Butry, L.M.; et al. Exome sequencing-based screening for BRCA1/2 expected pathogenic variants among adult biobank participants. JAMA Netw. Open 2018, 1, e182140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grzymski, J.; Elhanan, G.; Smith, E.; Rowan, C.; Slotnick, N.; Dabe, S.; Schlauch, K.; Read, R.; Metcalf, W.J.; Lipp, B.; et al. Population health genetic screening for tier 1 inherited diseases in northern nevada: 90% of at-risk carriers are missed. Biorxiv 2019, 1, 650549. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, M.S. Early Lessons from the Implementation of Genomic Medicine Programs. Annu. Rev. Genom. Hum. Genet. 2019, 20, 389–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, M.; Evans, J.P.; Angrist, M.; Chan, K.; Uhlmann, W.; Doyle, D.L.; Fullerton, S.M.; Ganiats, T.; Hagenkord, J.; Imhof, S. A Proposed Approach for Implementing Genomics-Based Screening Programs for Healthy Adults. Available online: https://nam.edu/a-proposed-approach-for-implementing-genomics-based-screening-programs-for-healthy-adults/ (accessed on 3 December 2018).

- Tier 1 Genomics Applications and Their Importance to Public Health 2014. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/genomics/implementation/toolkit/tier1.htm (accessed on 23 July 2019).

- Doble, B.; Schofield, D.J.; Roscioli, T.; Mattick, J.S. Prioritising the application of genomic medicine. NPJ Genom. Med. 2017, 2, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moyer, V.A. Force, Risk assessment, genetic counseling, and genetic testing for BRCA-related cancer in women: U.S. Preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann. Int. Med. 2014, 160, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, M.C.; Levy-Lahad, E.; Lahad, A. Population-based screening for BRCA1 and BRCA2: 2014 Lasker Award. JAMA 2014, 312, 1091–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahm, A.K.; Cragun, D.; Hunter, J.E.; Epstein, M.M.; Lowery, J.; Lu, C.Y.; Pawloski, P.A.; Sharaf, R.N.; Liang, S.Y.; Burnett-Hartman, A.N.; et al. Implementing universal lynch syndrome screening (IMPULSS): Protocol for a multi-site study to identify strategies to implement, adapt, and sustain genomic medicine programs in different organizational contexts. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabai-Kapara, E.; Lahad, A.; Kaufman, B.; Friedman, E.; Segev, S.; Renbaum, P.; Beeri, R.; Gal, M.; Grinshpun-Cohen, J.; Djemal, K.; et al. Levy-Lahad E. Population-based screening for breast and ovarian cancer risk due to BRCA1 and BRCA2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 14205–14210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.M.G.; Jungner, G. Principles and Practice of Screening for Disease 1968. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/37650 (accessed on 3 December 2019).

- Hylind, R.; Smith, M.; Rasmussen-Torvik, L.; Aufox, S. Great expectations: Patient perspectives and anticipated utility of non-diagnostic genomic-sequencing results. J. Community Genet. 2018, 9, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassy, J.L.; Christensen, K.D.; Schonman, E.F.; Blout, C.L.; Robinson, J.O.; Krier, J.B.; Diamond, P.M.; Lebo, M.; Machini, K.; Azzariti, D.R.; et al. The impact of whole-genome sequencing on the primary care and outcomes of healthy adult patients: A pilot randomized trial. Ann. Int. Med. 2017, 167, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manchanda, R.; Gaba, F. Population based testing for primary prevention: A systematic review. Cancers 2018, 10, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daly, M.B.; Pilarski, R.; Berry, M.; Buys, S.S.; Farmer, M.; Friedman, S.; Garber, J.E.; Kauff, N.D.; Khan, S.; Klein, C.; et al. NCCN guidelines insights: Genetic/familial high-risk assessment: Breast and ovarian, version 2.2017. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2017, 15, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hampel, H.; Bennett, R.L.; Buchanan, A.; Pearlman, R.; Wiesner, G.L. Guideline Development Group, American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics Professional Practice and Guidelines Committee and National Society of Genetic Counselors Practice Guidelines Committee. A practice guideline from the American college of medical genetics and genomics and the national society of genetic counselors: Referral indications for cancer predisposition assessment. Genet. Med. 2015, 17, 70–87. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Willoughby, A.; Andreassen, P.R.; Toland, A.E. Genetic testing to guide risk-stratified screens for breast cancer. J. Pers. Med. 2019, 9, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, M.L.B.; McCormick, C.Z.; Lazzeri, A.L.; Lindbuchler, D.M.; Hallquist, M.L.G.; Manickam, K.; Buchanan, A.H.; Rahm, A.K.; Giovanni, M.A.; Frisbie, L.; et al. A Model for genome-first care: Returning secondary genomic findings to participants and their healthcare providers in a large research cohort. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2018, 103, 328–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, A.H.; Manickam, K.; Meyer, M.N.; Wagner, J.K.; Hallquist, M.L.G.; Williams, J.L.; Rahm, A.K.; Williams, M.S.; Chen, Z.E.; Shah, C.K.; et al. Early cancer diagnoses through BRCA1/2 screening of unselected adult biobank participants. Genet. Med. 2018, 20, 554–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.S.; Buchanan, A.H.; Davis, F.D.; Faucett, W.A.; Hallquist, M.L.G.; Leader, J.B.; Martin, C.L.; McCormick, C.Z.; Meyer, M.N.; Murray, M.F.; et al. Patient-centered precision health in a learning health care system: geisinger’s genomic medicine experience. Health Aff. 2018, 37, 757–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NCCN Guidelines for BRCA Mutation-Positive Management: Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Breast and Ovarian (Vision 1.2018). 2018. Available online: https://jnccn.org/view/journals/jnccn/15/1/article-p9.xml (accessed on 31 January 2020).

- Burke, W.; Antommaria, A.H.; Bennett, R.; Botkin, J.; Clayton, E.W.; Henderson, G.E.; Holm, A.; Jarvik, G.P.; Khoury, M.J.; Knoppers, B.M.; et al. Recommendations for returning genomic incidental findings? We need to talk! Genet. Med. 2013, 15, 854–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, C.F.; Middleton, A.; Burton, H.; Cunningham, F.; Humphries, E.S.; Hurst, J.; Birney, E.; Firth, V.H. Policy challenges of clinical genome sequencing. BMJ 2013, 347, f6845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, M.R.; Biesecker, B.B.; Blout, C.L.; Christensen, K.D.; Amendola, L.M.; Bergstrom, K.L.; Biswas, S.; Bowling, K.M.; Brothers, K.B.; Conlin, L.K.; et al. Secondary findings from clinical genomic sequencing: Prevalence, patient perspectives, family history assessment, and health-care costs from a multisite study. Genet. Med. 2019, 21, 1100–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beattie, M.S.; Crawford, B.; Lin, F.; Vittinghoff, E.; Ziegler, J. Uptake, time course, and predictors of risk-reducing surgeries in BRCA carriers. Genet. Test Mol. Biomark. 2009, 13, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradbury, A.R.; Ibe, C.N.; Dignam, J.J.; Cummings, S.A.; Verp, M.; White, M.A.; Artioli, G.; Dudlicek, L.; Olopade, O.I. Uptake and timing of bilateral prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy among BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. Genet. Med. 2008, 10, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, D.G.; Lalloo, F.; Ashcroft, L.; Shenton, A.; Clancy, T.; Baildam, A.D.; Brain, A.; Hopwood, P.; Howell, A. Uptake of risk-reducing surgery in unaffected women at high risk of breast and ovarian cancer is risk, age, and time dependent. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2009, 18, 2318–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manchanda, R.; Legood, R.; Burnell, M.; McGuire, A.; Raikou, M.; Loggenberg, K.; Wardle, J.; Sanderson, S.; Gessler, S.; Side, L.; et al. Cost-effectiveness of population screening for BRCA mutations in Ashkenazi jewish women compared with family history-based testing. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2015, 107, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennette, C.S.; Gallego, C.J.; Burke, W.; Jarvik, G.P.; Veenstra, D.L. The cost-effectiveness of returning incidental findings from next-generation genomic sequencing. Genet. Med. 2014, 17, 587–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beitsch, P.D.; Whitworth, P.W.; Hughes, K.; Patel, R.; Rosen, B.; Compagnoni, G.; Baron, P.; Simmons, R.; Smith, L.A.; Grady, I.; et al. Underdiagnosis of Hereditary breast cancer: Are genetic testing guidelines a tool or an obstacle? J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, F.; Hirth, J.M.; Lin, Y.L.; Richardson, G.; Levine, L.; Berenson, A.B.; Kuo, Y.F. Use of BRCA mutation test in the U.S.; 2004–2014. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2017, 52, 702–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, M.E.; Flynn, B.S.; Stockdale, A. Primary care physician management, referral, and relations with specialists concerning patients at risk for cancer due to family history. Public Health Genom. 2013, 16, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drohan, B.; Roche, C.A.; Cusack, J.C., Jr.; Hughes, K.S. Hereditary breast and ovarian cancer and other hereditary syndromes: Using technology to identify carriers. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2012, 19, 1732–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Total Study Population | 59 | |

| BRCA Variant | ||

| BRCA1 | 12 | 20.3% |

| BRCA2 | 47 | 79.7% |

| Age (Mean), (Min, Max) Years | 53 | 24,90 |

| Age < 40 years old | 16 | 27.1% |

| Age ≥ 40 years old | 43 | 72.9% |

| Race | ||

| Black or African American | 1 | 1.7% |

| White | 58 | 98.3% |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic or Latino | 2 | 3.4% |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 57 | 96.6% |

| Previously Known | 11 | 18.6% |

| Previously Unknown | 48 | 81.4% |

| Prior Mastectomy | 2 | 3.4% |

| No Prior Mastectomy | 57 | 96.6% |

| Prior Oophorectomy | 8 | 13.6% |

| No Prior Oophorectomy | 51 | 86.4% |

| Family History of BRCA Relevant Cancer | ||

| With Family History of BRCA Relevant Cancer | 38 | 64.4% |

| Without Family History of BRCA Relevant Cancer | 12 | 20.3% |

| Missing Family History Information | 9 | 15.3% |

| Pre-Disclosure | Post-Disclosure | P-Value | Average Difference Per Patient (Post—Pre-Disclosure) | Boot-Strapping 95% CI | Boot-Strapping p-Value | |

| Patient with any outpatient visits, No. (%) | 53 (89.83) | 52 (88.14) | 1.00 a | |||

| Patients with any inpatient admissions, No. (%) | 24 (40.68) | 20 (33.90) | 0.56 a | |||

| Patient with any other encounter visits, No. (%) | 44 (74.58) | 44 (74.58) | 1.00 a | |||

| No. of Outpatient visits per patient, Mean (SD) | 7.37 (6.25) | 6.93 (5.34) | 0.52 | −0.44 | (−1.76, 0.88) | 0.51 |

| No. Inpatient encounters per patient, mean (SD) | 0.63 (1.02) | 0.51 (0.86) | 0.49 | −0.12 | (−0.46, 0.22) | 0.49 |

| Sub-cohort of Previously Unknown (N = 48) | Pre-Disclosure | Post-Disclosure | P-Value | Average Difference Per Patient (Post—Pre-Disclosure) | Boot-Strapping 95% CI | Boot-Strapping p-Value |

| Patient with any outpatient visits, No. (%) | 43 (89.58) | 41 (85.42) | 0.73 a | |||

| Patients with any inpatient admissions, No. (%) | 18 (37.50) | 15 (31.25) | 0.66 a | |||

| Patient with any other encounter visits, No. (%) | 35 (72.92) | 34 (70.83) | 1.00 a | |||

| No. of Outpatient visits per patient, Mean (SD) | 7.13 (6.54) | 6.92 (5.57) | 0.79 | −0.21 | (−1.72, 1.30) | 0.79 |

| No. Inpatient encounters per patient, mean (SD) | 0.58 (1.03) | 0.48 (0.85) | 0.61 | −0.10 | (−0.49, 0.28) | 0.59 |

| Entire Cohort (N = 59) | Pre-Disclosure | Post-Disclosure | ||||

| Average | Median | Interquartile Range | Average | Median | Interquartile Range | |

| Total costs per patient ($) | $18,821 | $4956 | ($1240, $19,318) | $19,359 | $4,622 | ($1084, $27,738) |

| Average Difference Per Patient | $538 (p = 0.76 a) | |||||

| Pre-Disclosure | Post-Disclosure | |||||

| Patients Previously Unknown (N = 48) | Average | Median | Interquartile Range | Average | Median | Interquartile Range |

| Total costs per patient ($) | $15,122 | $4197 | ($1157, $17,381) | $17,699 | $4955 | ($1062, $22,906) |

| Average Difference Per Patient | $2578 (p = 0.76 a) | |||||

| (No., %) | N | N(MAST) | N(OOPH) | N(MAMMO/MRI) | MAST | OOPH | MAMMO | MRI | MAMMO or MRI | CHEMO | GC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 59 | 57 | 51 | 58 | 2 (3.5) | 6 (11.8) | 27 (46.6) | 19 (32.8) | 29 (50.0) | 3 (5.1) | 29 (49.2) |

| Age <40 | 16 | 15 | 13 | 15 | 1 (6.7) | 1 (7.7) | 6 (40.0) | 5 (33.3) | 7 (46.7) | 1 (6.3) | 6 (37.5) |

| Age ≥40 | 43 | 42 | 38 | 43 | 1 (2.4) | 5 (13.2) | 21 (48.8) | 14 (32.6) | 22 (51.2) | 2 (4.7) | 23 (53.5) |

| BRCA1 | 12 | 10 | 8 | 12 | 0 (0) | 1 (12.5) | 5 (41.7) | 4 (33.3) | 6 (50.0) | 1 (8.3) | 1 (8.3) |

| BRCA2 | 47 | 47 | 43 | 46 | 2 (4.3) | 5 (11.6) | 22 (47.8) | 15 (32.6) | 23 (50.0) | 2 (4.3) | 28 (59.6) |

| Previously Known | 11 | 9 | 8 | 11 | 0 (0) | 2 (25) | 5 (45.5) | 5 (45.5) | 6 (54.5) | 2 (18.2) | 1 (9.1) |

| Previously Unknown | 48 | 48 | 43 | 47 | 2 (4.2) | 4 (9.3) | 22 (46.8) | 14 (29.8) | 23 (48.9) | 1 (2.1) | 28 (58.3) |

| With Family History | 38 | 36 | 32 | 38 | 2 (5.6) | 4 (12.5) | 21 (55.3) | 15 (39.5) | 23 (60.5) | 1 (2.6) | 20 (52.6) |

| With No Family History | 12 | 12 | 11 | 11 | 0 (0) | 2 (18.2) | 6 (54.5) | 4 (36.4) | 6 (54.5) | 2 (16.7) | 9 (75.0) |

| Missing Family History | 9 | 9 | 8 | 9 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hao, J.; Hassen, D.; Manickam, K.; Murray, M.F.; Hartzel, D.N.; Hu, Y.; Liu, K.; Rahm, A.K.; Williams, M.S.; Lazzeri, A.; et al. Healthcare Utilization and Costs after Receiving a Positive BRCA1/2 Result from a Genomic Screening Program. J. Pers. Med. 2020, 10, 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm10010007

Hao J, Hassen D, Manickam K, Murray MF, Hartzel DN, Hu Y, Liu K, Rahm AK, Williams MS, Lazzeri A, et al. Healthcare Utilization and Costs after Receiving a Positive BRCA1/2 Result from a Genomic Screening Program. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2020; 10(1):7. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm10010007

Chicago/Turabian StyleHao, Jing, Dina Hassen, Kandamurugu Manickam, Michael F. Murray, Dustin N. Hartzel, Yirui Hu, Kunpeng Liu, Alanna Kulchak Rahm, Marc S. Williams, Amanda Lazzeri, and et al. 2020. "Healthcare Utilization and Costs after Receiving a Positive BRCA1/2 Result from a Genomic Screening Program" Journal of Personalized Medicine 10, no. 1: 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm10010007

APA StyleHao, J., Hassen, D., Manickam, K., Murray, M. F., Hartzel, D. N., Hu, Y., Liu, K., Rahm, A. K., Williams, M. S., Lazzeri, A., Buchanan, A., Sturm, A., & Snyder, S. R. (2020). Healthcare Utilization and Costs after Receiving a Positive BRCA1/2 Result from a Genomic Screening Program. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 10(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm10010007