Optical Coherence Tomography and Angiography in Hydroxychloroquine Retinopathy: A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

Optical Coherence Tomography

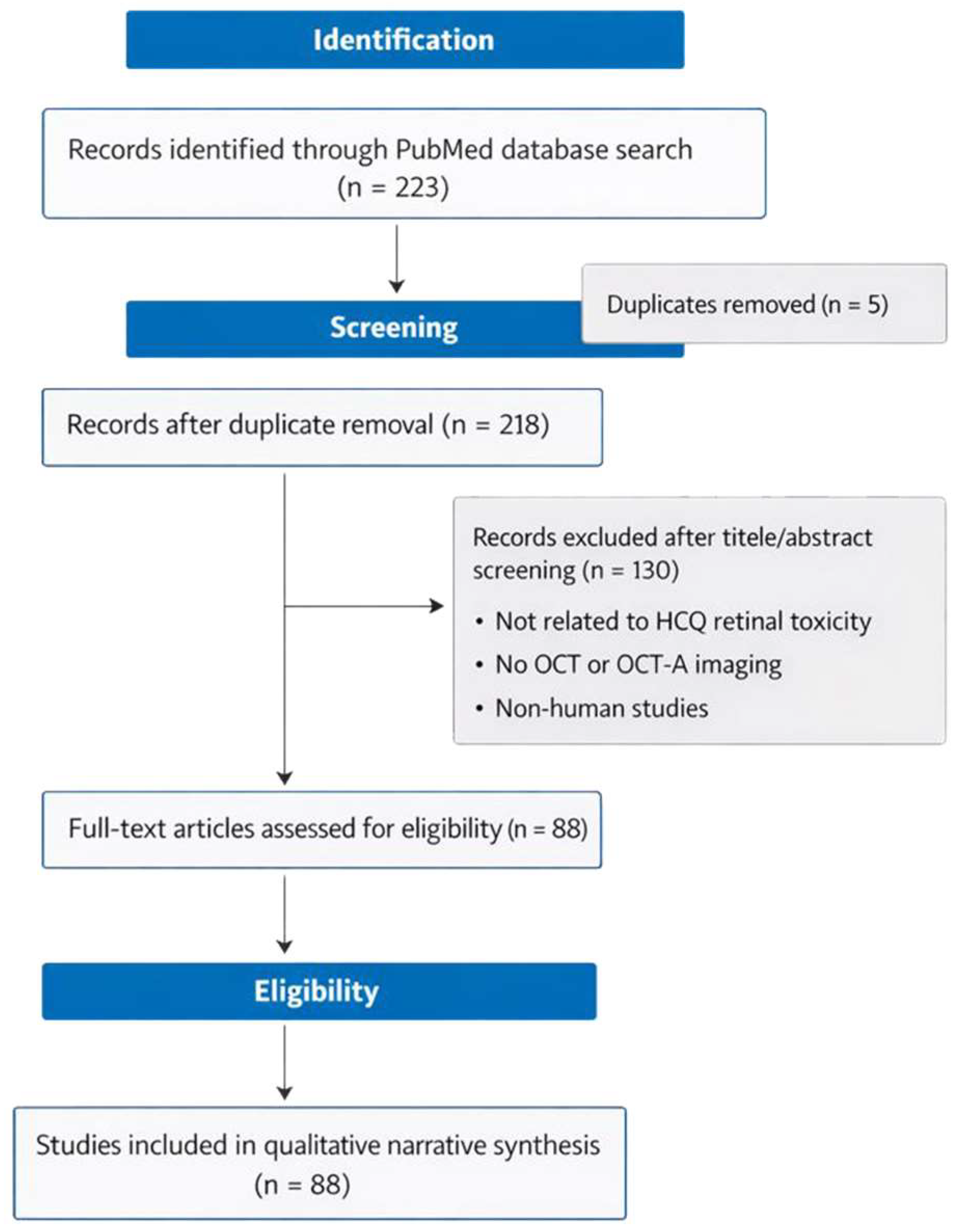

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Outer Retinal Alterations

3.2. Elipsoid Zone

3.3. Inner Retinal Alterations

3.4. Choroid

3.5. OCT-A Findings

4. Discussion

4.1. Toward a Diagnostic Hierarchy and Personalized Screening

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BCVA | Best corrected visual acuity |

| CC | Choriocapillaris |

| CCP | Choriocapillaris plexus |

| CCT | Choriocapillaris thickness |

| CMT | Central macula thickness |

| CQ | Chloroquine |

| CRP | C Reactive Protein |

| CT | Choroidal thickness |

| CVI | Choroidal vascular index |

| DAI | Disease activity index |

| DLD | Drusen-like deposit |

| DMIR | Deep macular ischemia ratio |

| DTMI | Deep total microvascular index |

| DVP | Deep vascular plexus |

| ELM | External limiting membrane |

| ESR | Erythrocyte sedimentation rate |

| EZ | Ellipsoid zone |

| FAF | Fundus autofluorescence |

| FAZ | Foveal avascular zone |

| FFA | Fundus fluorescein angiography |

| FD | Flow-related deficits |

| FT | Foveal thickness |

| G | Group |

| GCL | Ganglion cell layer |

| GCIPL | Ganglion cell inner-plexiform layer |

| HCR | Hydroxychloroquine retinopathy |

| HCQ | Hydroxychloroquine |

| HFL | Henle fiber layer |

| ID | Interdigitation |

| IL | Interleukin |

| Ig | Immunoglobulin |

| INL | Inner nuclear layer |

| IPL | Inner plexiform layer |

| IR | Inner retina |

| IRL | Inner retinal layers |

| IRT | Inner retina thickness |

| IS | Inner segment |

| JSLE | Juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus |

| LCA | Luminal choroidal area |

| mfERG | Multifocal electroretinogram |

| MI | Macular integrity |

| MT | Macular thickness |

| NIR | Near-infrared reflectance |

| NIR-AF | Near-infrared autofluorescence |

| ONL | Outer nuclear layer |

| OCT | Optical coherence tomography |

| OCT-A | Optical coherence tomography angiography |

| OR | Outer retina |

| ORL | Outer retinal layers |

| ORT | Outer retina thickness |

| OS | Outer segment |

| PR | Photoreceptor |

| PRL | Photoreceptor layer |

| pRNFL | Peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer |

| QOL | Quality of life |

| RA | Rheumatoid arthritis |

| RGC | Retinal ganglion cell |

| RPC | Radial peripapillary capillaries |

| RPE | Retinal pigmented epithelium |

| RNFL | Retinal nerve fiber layer |

| RT | Retinal thickness |

| SCA | Stromal choroidal area |

| SFCT | Subfoveal choroidal thickness |

| SJS | Sjögren’s syndrome |

| SLE | Systemic lupus erythematosus |

| SLICC-SDI | Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics–Systemic Damage Index |

| SMAR | Superficial macular area ratio |

| SMIR | Superficial macular ischemia ratio |

| SS | Systemic sclerosis |

| STMI | Superficial total microvascular index |

| SVP | Superficial vascular plexus |

| SW-AF | Short-wave autofluorescence |

| TCA | Total choroidal area |

| V | Visit |

| VA | Visual acuity |

| VD | Vessel density |

| VF | Visual field |

| VIS | Visible-light |

| VRQOL | Vision-related quality of life |

References

- Ferreira, A.; Anjos, R.; José-Vieira, R.; Afonso, M.; Abreu, A.C.; Monteiro, S.; Macedo, M.; Andrade, J.P.; Furtado, M.J.; Lume, M. Application of optical coherence tomography angiography for microvascular changes in patients treated with hydroxychloroquine: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Graefe’s Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2023, 261, 2221–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, I.H.; Issa, P.C.; Ahn, S.J. Hydroxychloroquine-induced Retinal Toxicity. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1196783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolen, J.S.; Landewé, R.B.M.; Bergstra, S.A.; Kerschbaumer, A.; Sepriano, A.; Aletaha, D.; Caporali, R.; Edwards, C.J.; Hyrich, K.L.; Pope, J.E.; et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2022 update. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2023, 82, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanouriakis, A.; Kostopoulou, M.; Andersen, J.; Aringer, M.; Arnaud, L.; Bae, S.-C.; Boletis, J.; Bruce, I.N.; Cervera, R.; Doria, A.; et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of systemic lupus erythematosus: 2023 update. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2024, 83, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.; Kalra, G.; Al-Sheikh, M.; Chhablani, J. Mimickers of hydroxychloroquine retinal toxicity. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2024, 52, 1003–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snow, Z.; Seely, K.; Barrett, S.; Pecha, J.; Goldhardt, R. Target in Sight: A Comprehensive Review of Hydroxychloroquine-Induced Bull’s Eye Maculopathy. Curr. Ophthalmol. Rep. 2024, 12, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheong, K.; Ong, C.; Chandrasekaran, P.; Zhao, J.; Teo, K.; Mathur, R. Review of Retinal Imaging Modalities for Hydroxychloroquine Retinopathy. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donica, V.C.; Alexa, A.I.; Pavel, I.A.; Danielescu, C.; Ciapă, M.A.; Donica, A.L.; Bogdănici, C.M. The Evolvement of OCT and OCT-A in Identifying Multiple Sclerosis Biomarkers. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 3031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montesel, A.; Sacconi, R.; La Rubia, P.; Querques, G. Impact of cumulative dose of hydroxychloroquine on retinal structures. Graefe’s Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2024, 263, 235–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melles, R.B.; Marmor, M.F. Rapid Macular Thinning Is an Early Indicator of Hydroxychloroquine Retinal Toxicity. Ophthalmology 2022, 129, 1004–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farvardin, M.; Peiravian, P.; Ravankhah, M.; Nowroozzadeh, M.H. Evaluation of changes in thickness of macular sublayers in patients using Hydroxychloroquine: A cross sectional case-control study and literature review. Cutan. Ocul. Toxicol. 2024, 44, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salameh, N.; Doumit, C.A.; Jalkh, E.; Nehme, J. Association between hydroxychloroquine intake and damage to the outer nuclear layer in eyes without manifest retinal toxicity. BMC Ophthalmol. 2024, 24, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, A.K.; Wang, J.; Alonzo, B.; Yi, J.; Kashani, A.H. Photoreceptor outer segment reflectivity with ultrahigh resolution visible light optical coherence tomography in systemic hydroxychloroquine use. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2025, 14, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitay, A.M.; Hanson, J.V.M.; Hasan, N.; Driban, M.; Chhablani, J.; Barthelmes, D.; Gerth-Kahlert, C.; Al-Sheikh, M. Functional and Morphological Characteristics of the Retina of Patients with Drusen-like Deposits and Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Treated with Hydroxychloroquine: A Retrospective Study. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarassoly, K.; Miraftabi, A.; Sedaghat, A.; Parvaresh, M.M. Analysis of the outer retinal thickness pixel maps for the screening of hydroxychloroquine retinopathy. Int. Ophthalmol. 2022, 43, 1737–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrelli, E.; Battista, M.; Cascavilla, M.L.; Viganò, C.; Borghesan, F.; Nicolini, N.; Clemente, L.; Sacconi, R.; Barresi, C.; Marchese, A.; et al. Impact of Structural Changes on Multifocal Electroretinography in Patients With Use of Hydroxychloroquine. Investig. Opthalmology Vis. Sci. 2021, 62, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, M.A.; Beltagi, A.S.; Abdellatif, M.A.; Awadalla, M.A. Visual Impact of Early Hydroxychloroquine-Related Retinal Structural Changes in Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Ophthalmologica 2021, 244, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manoj, M.; Sahoo, R.R.; Singh, A.; Hazarika, K.; Bafna, P.; Kaur, A.; Wakhlu, A. Prevalence of hydroxychloroquine retinopathy with long-term use in a cohort of Indian patients with rheumatic diseases. Rheumatol. Int. 2021, 41, 929–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.E.; Ahn, S.J.; Woo, S.J.; Park, K.H.; Lee, B.R.; Lee, Y.-K.; Sung, Y.-K. Use of OCT Retinal Thickness Deviation Map for Hydroxychloroquine Retinopathy Screening. Ophthalmology 2021, 128, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, H.; Lotery, A.; Price, E.J.; Smith, G.T. An objective method of diagnosing hydroxychloroquine maculopathy. Eye 2020, 35, 1922–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, S.; Kumar, P.; Moulick, P.S.; Vats, S. Spectral domain optical coherence tomography–based prevalence of hydroxychloroquine maculopathy in Indian patients on hydroxychloroquine therapy: A utopia of underdiagnosis. Med. J. Armed Forces India 2020, 76, 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias-Santos, A.; Ferreira, J.T.; Pinheiro, S.; Cunha, J.P.; Alves, M.; Papoila, A.L.; Moraes-Fontes, M.F.; Proença, R. Ocular involvement in systemic lupus erythematosus patients: A paradigm shift based on the experience of a tertiary referral center. Lupus 2020, 29, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casado, A.; López-de-Eguileta, A.; Fonseca, S.; Muñoz, P.; Demetrio, R.; Gordo-Vega, M.A.; Cerveró, A. Outer Nuclear Layer Damage for Detection of Early Retinal Toxicity of Hydroxychloroquine. Biomedicines 2020, 8, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral, R.T.D.S.; Klumb, E.M.; Couto, M.I.N.N.; Carneiro, S. Evaluation of toxic retinopathy caused by antimalarial medications with spectral domain optical coherence tomography. Arq. Bras. Oftalmol. 2019, 82, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Božinovic, M.S.T.; Babic, G.S.; Petrovic, M.; Karadžic, J.; Vulovic, T.Š.; Trenkic, M. Role of optical coherence tomography in the early detection of macular thinning in rheumatoid arthritis patients with chloroquine retinopathy. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2019, 24, 55. [Google Scholar]

- Cakir, A.; Ozturan, Ş.G.; Yildiz, D.; Erden, B.; Bolukbasi, S.; Tascilar, E.K.; Yanmaz, M.N.; Elcioglu, M.N. Evaluation of photoreceptor outer segment length in hydroxychloroquine users. Eye 2019, 33, 1321–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrity, S.T.; Jung, J.Y.; Zambrowski, O.; Pichi, F.; Su, D.; Arya, M.; Waheed, N.K.; Duker, J.S.; Chetrit, Y.; Miserocchi, E.; et al. Early hydroxychloroquine retinopathy: Optical coherence tomography abnormalities preceding Humphrey visual field defects. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 103, 1600–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allahdina, A.M.; Chen, K.G.; Alvarez, J.A.; Wong, W.T.; Chew, E.Y.; Cukras, C.A. Longitudinal Changes in Eyes with Hydroxychloroquine Retinal Toxicity. Retina 2019, 39, 473–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, B.H.; Marmor, M.F. Sequential Changes in Hydroxychloroquine Retinopathy up to 20 Years After Stopping the Drug: Implications for Mild Versus Severe Toxicity. Retina 2019, 39, 492–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruberto, G.; Bruttini, C.; Tinelli, C.; Cavagna, L.; Bianchi, A.; Milano, G. Early morpho-functional changes in patients treated with hydroxychloroquine: A prospective cohort study. Graefe’s Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2018, 256, 2201–2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allahdina, A.M.; Stetson, P.F.; Vitale, S.; Wong, W.T.; Chew, E.Y.; Ferris, F.L., III; Sieving, P.A.; Cukras, C. Optical Coherence Tomography Minimum Intensity as an Objective Measure for the Detection of Hydroxychloroquine Toxicity. Investig. Opthalmology Vis. Sci. 2018, 59, 1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.J.; Joung, J.; Lee, S.H.; Lee, B.R. Intravitreal dexamethasone implant therapy for the treatment of cystoid macular Oedema due to hydroxychloroquine retinopathy: A case report and literature review. BMC Ophthalmol. 2018, 18, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.-W.; Kim, Y.Y.; Lee, H.; Park, S.-H.; Kim, S.-K.; Choe, J.-Y. Risk of Retinal Toxicity in Longterm Users of Hydroxychloroquine. J. Rheumatol. 2017, 44, 1674–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.J.; Joung, J.; Lim, H.W.; Lee, B.R. Optical Coherence Tomography Protocols for Screening of Hydroxychloroquine Retinopathy in Asian Patients. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2017, 184, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eo, D.-R.; Lee, M.G.; Ham, D.-I.; Kang, S.W.; Lee, J.; Cha, H.S.; Koh, E.; Kim, S.J. Frequency and Clinical Characteristics of Hydroxychloroquine Retinopathy in Korean Patients with Rheumatologic Diseases. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2017, 32, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, S.-K.; Lai, T.-T.; Hsieh, Y.-T. Optical coherence tomography characteristics in hydroxychloroquine retinopathy and the correlations with visual deterioration in Taiwanese. Taiwan J. Ophthalmol. 2024, 14, 565–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gencoglu, A.Y.; Ağın, A.; Colak, D.; Un, Y.; Ozturk, Y. Decreased peri-parafoveal RPE, EZ and ELM intensity: A novel predictive biomarker for hydroxychloroquine retinal toxicity. Graefe’s Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2024, 262, 3543–3552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talcott, K.E.; Kalra, G.; Cetin, H.; Cakir, Y.; Whitney, J.; Budrevich, J.; Reese, J.L.; Srivastava, S.K.; Ehlers, J.P. Automated Evaluation of Ellipsoid Zone At-Risk Burden for Detection of Hydroxychloroquine Retinopathy. J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alieldin, R.A.; Boonarpha, N.; Saedon, H. Outcomes of screening for hydroxychloroquine retinopathy at the Manchester Royal Eye Hospital: 2 years’ audit. Eye 2022, 37, 1410–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.E.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, Y.H.; Ahn, S.J. Clock-hour topography and extent of outer retinal damage in hydroxychloroquine retinopathy. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 11809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalra, G.; Talcott, K.E.; Kaiser, S.; Ugwuegbu, O.; Hu, M.; Srivastava, S.K.; Ehlers, J.P. Machine Learning–Based Automated Detection of Hydroxychloroquine Toxicity and Prediction of Future Toxicity Using Higher-Order OCT Biomarkers. Ophthalmol. Retin. 2022, 6, 1241–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayakar, G.; De Silva, T.; Cukras, C.A. Visual Field Sensitivity Prediction Using Optical Coherence Tomography Analysis in Hydroxychloroquine Toxicity. Investig. Opthalmology Vis. Sci. 2022, 63, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabit, J.Y.; Hocaoglu, M.; Moder, K.G.; Barkmeier, A.J.; Smith, W.M.; O’Byrne, T.J.; Crowson, C.S.; Duarte-García, A. Risk of hydroxychloroquine retinopathy in the community. Rheumatology 2021, 61, 3172–3179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.J.; Seo, E.J.; Kim, K.E.; Kim, Y.J.; Lee, B.R.; Kim, J.-G.; Yoon, Y.H.; Lee, J.Y. Long-Term Progression of Pericentral Hydroxychloroquine Retinopathy. Ophthalmology 2021, 128, 889–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jauregui, R.; Parmann, R.; Nuzbrokh, Y.; Tsang, S.H.; Sparrow, J.R. Spectral-Domain Optical Coherence Tomography Is More Sensitive for Hydroxychloroquine-Related Structural Abnormalities Than Short-Wavelength and Near-Infrared Autofluorescence. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2020, 9, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobbett, A.; Kotagiri, A.; Bracewell, C.; Smith, J. Two years’ experience of screening for hydroxychloroquine retinopathy. Eye 2020, 35, 1171–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browning, D.J.; Easterbrook, M.; Lee, C. The 2016 American Academy of Ophthalmology Hydroxychloroquine Dosing Guidelines For Short, Obese Patients. Ophthalmol. Retin. 2019, 3, 809–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ugwuegbu, O.; Uchida, A.; Singh, R.P.; Beven, L.; Hu, M.; Kaiser, S.; Srivastava, S.K.; Ehlers, J.P. Quantitative assessment of outer retinal layers and ellipsoid zone mapping in hydroxychloroquine retinopathy. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2018, 103, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arndt, C.; Costantini, M.; Chiquet, C.; Afriat, M.; Berthemy, S.; Vasseur, V.; Ducasse, A.; Mauget-Faÿsse, M. Comparison between multifocal ERG and C-Scan SD-OCT (“en face” OCT) in patients with a suspicion of antimalarial retinal toxicity: Preliminary results. Doc. Ophthalmol. 2018, 136, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.H.; Park, Y.-H.; Park, Y.G. Subclinical Detection of Hydroxychloroquine-Induced Retinopathy in Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematous Using Multifocal Electroretinography and Optical Coherence Tomography. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonalcan, V.; Çakir, B.; Aksoy, N.Ö.; Gündoğdu, K.Ö.; Şen, E.B.T.; Alagöz, G. The assessment of structural and functional test results for early detection of hydroxychloroquine macular toxicity. Int. Ophthalmol. 2024, 44, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mimier-Janczak, M.K.; Kaczmarek, D.; Proc, K.; Misiuk-Hojło, M.; Kaczmarek, R. Subclinical retinopathy in systemic lupus erythematosus patients—Optical Coherence Tomography study. Rheumatology 2023, 61, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agcayazi, S.B.E.; Gurlu, V.; Alacamli, G. Decreased perifoveal ganglion cell complex thickness—A first sign for macular damage in patients using hydroxychloroquine. Rom. J. Ophthalmol. 2023, 67, 146–151. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.E.; Kim, Y.H.; Kim, J.; Ahn, S.J. Macular Ganglion Cell Complex and Peripapillary Retinal Nerve Fiber Layer Thicknesses in Hydroxychloroquine Retinopathy. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2023, 245, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, K.; Porter, H.; Cole, J., II; Pandya, H.K.; Basu, S.K.; Khanam, S.; Chiu, C.-Y.; Shah, V.; Stephenson, D.J.; Chalfant, C.E.; et al. Correction: Hydroxychloroquine Causes Early Inner Retinal Toxicity and Affects Autophagosome–Lysosomal Pathway and Sphingolipid Metabolism in the Retina. Mol. Neurobiol. 2022, 59, 6611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Membreno, R.F.; De Silva, T.; Agrón, E.; Keenan, T.D.L.; Cukras, C.A. Quantitative analysis of optical coherence tomography imaging in patients with different severities of hydroxychloroquine toxicity. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 107, 849–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurna, S.A.; Kanar, H.S.; Garlı, M.; Çakır, N. Evaluation of the role of spectral-domain optical coherence tomography in the early detection of macular and ganglion cell complex thickness changes in patients with rheumatologic diseases taking hydroxychloroquine. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2022, 38, 102741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godinho, G.; Madeira, C.; Falcão, M.; Penas, S.; Dinah-Bragança, T.; Brandão, E.; Carneiro, Â.; Santos-Silva, R.; Falcão-Reis, F.; Beato, J. Longitudinal Retinal Changes Induced by Hydroxychloroquine in Eyes without Retinal Toxicity. Ophthalmic Res. 2020, 64, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín-Iglesias, D.; Artaraz, J.; Fonollosa, A.; Ugarte, A.; Arteagabeitia, A.; Ruiz-Irastorza, G. Evolution of retinal changes measured by optical coherence tomography in the assessment of hydroxychloroquine ocular safety in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 2019, 28, 555–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, P.; Nunes, A.; Farinha, C.; Teixeira, D.; Pires, I.; Silva, R. Structural and Functional Characterization of the Retinal Effects of Hydroxychloroquine Treatment in Healthy Eyes. Ophthalmologica 2019, 241, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conigliaro, P.; Triggianese, P.; Draghessi, G.; Canofari, C.; Aloe, G.; Chimenti, M.; Valeri, C.; Nucci, C.; Perricone, R.; Cesareo, M. Evidence for the Detection of Subclinical Retinal Involvement in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus and Sjögren Syndrome: A Potential Association with Therapies. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2018, 177, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.J.; Kim, S.J.; Han, J.C.; Eo, D.R.; Lee, M.G.; Ham, D.-I.; Kang, S.W.; Kee, C.; Lee, J.; Cha, H.-S.; et al. Peripapillary Retinal Nerve Fiber Layer Thicknesses Did Not Change in Long-term Hydroxychloroquine Users. Korean J. Ophthalmol. 2018, 32, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulut, M.; Kazım, E.R.O.L.M.; Toslak, D.; Akidan, M.; Başar, E.K.A.Y.A.; Fatih, Ç.A.Y.H. A New Objective Parameter in Hydroxychloroquine-Induced Retinal Toxicity Screening Test: Macular Retinal Ganglion Cell-Inner Plexiform Layer Thickness. Arch. Rheumatol. 2018, 33, 052–058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telek, H.H.; Yesilirmak, N.; Sungur, G.; Ozdemir, Y.; Yesil, N.K.; Ornek, F. Retinal toxicity related to hydroxychloroquine in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis. Doc. Ophthalmol. 2017, 135, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, E.; Yakar, K.; Demirag, M.D.; Gok, M. Macular ganglion cell–inner plexiform layer thickness for detection of early retinal toxicity of hydroxychloroquine. Int. Ophthalmol. 2017, 38, 1635–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias-Peso, B.; González, M.C.; García-Navarro, D.; del Tiempo, M.P.R.; Barón, N.P.; Sáez-Comet, L.; Ruiz-Moreno, O.; Bartol-Puyal, F.; Méndez-Martínez, S.; Júlvez, L.P. Automated analysis of choroidal thickness in patients with systemic lupus erithematosus treated with hydroxychloroquine. Int. Ophthalmol. 2024, 44, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasan, N.; Driban, M.; Mohammed, A.R.; Schwarz, S.; Yoosuf, S.; Barthelmes, D.; Vupparaboina, K.K.; Al-Sheikh, M.; Chhablani, J. Effects of hydroxychloroquine therapy on choroidal volume and choroidal vascularity index. Eye 2023, 38, 620–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halouani, S.; Le, H.M.; Querques, G.; Borrelli, E.; Sacconi, R.; Battista, M.; Jung, C.; Souied, E.H.; Miere, A. Choroidal Vascularity Index in Hydroxychloroquine Toxic Retinopathy: A Quantitative Comparative Analysis Using Enhanced Depth Imaging In Spectral Domain Optical Coherence Tomography. Retina 2023, 43, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ru, L.; Xu, J.; Lin, Z.; Cao, L.; Zhang, L. Analysis of choroidal thickness in juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus and its correlation with laboratory tests. BMC Ophthalmol. 2023, 23, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kukan, M.; Driban, M.; Vupparaboina, K.K.; Schwarz, S.; Kitay, A.M.; Rasheed, M.A.; Busch, C.; Barthelmes, D.; Chhablani, J.; Al-Sheikh, M. Structural Features of Patients with Drusen-like Deposits and Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polat, O.A.; Okçu, M.; Yılmaz, M. Hydroxychloroquine treatment alters retinal layers and choroid without apparent toxicity in optical coherence tomography. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2022, 38, 102806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.J.; Ryu, S.J.; Lim, H.W.; Lee, B.R. Toxic Effects of Hydroxychloroquine on the Choroid: Evidence From Multimodal Imaging. Retina 2019, 39, 1016–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.J.; Ryu, S.J.; Joung, J.Y.; Lee, B.R. Choroidal Thinning Associated With Hydroxychloroquine Retinopathy. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2017, 183, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karti, O.; Ayhan, Z.; Zengin, M.O.; Kaya, M.; Kusbeci, T. Choroidal Thickness Changes in Rheumatoid Arthritis and the Effects of Short-term Hydroxychloroquine Treatment. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2017, 26, 770–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, J.; Rothwell, R.; Oliveira, M.; Rodrigues, D.; Fonseca, S.; Varandas, R.; Ribeiro, L. Choroid thickness profile in patients with lupus nephritis. Lupus 2019, 28, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Zhang, J.; Yin, X.; Xiang, Z.; Qiu, W.; Huang, A.M.; Wang, L.; Lv, Q.; Liu, Z. Inter-eye asymmetry of microvascular density in patients on hydroxychloroquine therapy by optical coherence tomography angiography. Microvasc. Res. 2025, 157, 104747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartol-Puyal, F.D.A.; González, M.C.; Arias-Peso, B.; Navarro, D.G.; Méndez-Martínez, S.; del Tiempo, M.P.R.; Comet, L.S.; Júlvez, L.P. Vision-Related Quality of Life in Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Healthcare 2024, 12, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araújo, O.; Casaroli-Marano, R.P.; Hernández-Rodríguez, J.; Figueras-Roca, M.; Budi, V.; Morató, M.; Hernández-Negrín, H.; Ríos, J.; Adan, A.; Espinosa, G.; et al. New proposal for a multimodal imaging approach for the subclinical detection of hydroxychloroquine-induced retinal toxicity in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. BMJ Open Ophthalmol. 2024, 9, e001608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leclaire, M.D.; Esser, E.L.; Dierse, S.; Koch, R.; Zimmermann, J.A.; Storp, J.J.; Gunnemann, M.-L.; Lahme, L.; Eter, N.; Mihailovic, N. Microvascular Density Analysis of Patients with Inactive Systemic Lupus Erythematosus—A Two-Year Follow-Up Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography Study. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 2979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Pan, M.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, F.; Shuai, Z. Evaluation of early retinal changes in patients on long-term hydroxychloroquine using optical coherence tomography angiography. Ther. Adv. Drug Saf. 2024, 15, 20420986231225851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.-C.; Luo, S.-L.; Lv, M.-N.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.-B.; Yu, S.-J.; Wu, R. Effect of hydroxychloroquine blood concentration on the efficacy and ocular toxicity of systemic lupus erythematosus. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 7674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilijević, J.B.; Kovačević, I.M.; Dijana, R.; Dačić, B.; Marić, G.; Stanojlović, S. Optical coherence tomography angiography parameters in patients taking hydroxychloroquine therapy. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2023, 71, 3399–3405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esser, E.L.; Zimmermann, J.A.; Storp, J.J.; Eter, N.; Mihailovic, N. Retinal microvascular density analysis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with hydroxychloroquine. Graefe’s Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2022, 261, 1433–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Shi, W.; Chen, J.; Li, Q.J.; Wei, H.; Xu, S.H.; Kang, M.; Huang, H.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; et al. Retinal alterations in evaluation of rheumatoid arthritis with chloroquine treatment: A new approach. J. Biophotonics 2023, 16, e202300133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Zou, J.; Ge, Q.-M.; Liao, X.-L.; Pan, Y.-C.; Wu, J.-L.; Su, T.; Zhang, L.-J.; Liang, R.-B.; Shao, Y. Ocular microvascular alteration in Sjögren’s syndrome treated with hydroxychloroquine: An OCTA clinical study. Ther. Adv. Chronic Dis. 2023, 14, 20406223231164498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subasi, S.; Kucuk, K.D.; San, S.; Cefle, A.; Tokuc, E.O.; Balci, S.; Yazici, A. Macular and peripapillary vessel density alterations in a large series of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus without ocular involvement. Graefe’s Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2022, 260, 3543–3552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halouani, S.; Le, H.M.; Cohen, S.Y.; Terkmane, N.; Herda, N.; Souied, E.H.; Miere, A. Choriocapillaris Flow Deficits Quantification in Hydroxychloroquine Retinopathy Using Swept-Source Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forte, R.; Haulani, H.; Dyrda, A.; Jürgens, I. Swept source optical coherence tomography angiography in patients treated with hydroxychloroquine: Correlation with morphological and functional tests. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 105, 1297–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhlaghi, M.; Kianersi, F.; Radmehr, H.; Dehghani, A.; Beni, A.N.; Noorshargh, P. Evaluation of optical coherence tomography angiography parameters in patients treated with Hydroxychloroquine. BMC Ophthalmol. 2021, 21, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinar, E.; Yuce, B.; Aslan, F. Evaluation of retinal and choroidal microvascular changes in patients who received hydroxychloroquine by optical coherence tomography angiography. Arq. Bras. Oftalmol. 2021, 84, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarakcioglu, H.N.; Ozkaya, A.; Yigit, U. Is optical coherence tomography angiography a useful tool in the screening of hydroxychloroquine retinopathy? Int. Ophthalmol. 2020, 41, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenfant, T.; Salah, S.; Leroux, G.; Bousquet, E.; Le Guern, V.; Chasset, F.; Francès, C.; Morel, N.; Chezel, J.; Papo, T.; et al. Risk factors for hydroxychloroquine retinopathy in systemic lupus erythematosus: A case–control study with hydroxychloroquine blood-level analysis. Rheumatology 2020, 59, 3807–3816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihailovic, N.; Leclaire, M.D.; Eter, N.; Brücher, V.C. Altered microvascular density in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus treated with hydroxychloroquine—An optical coherence tomography angiography study. Graefe’s Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2020, 258, 2263–2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozek, D.; Onen, M.; Karaca, E.E.; Omma, A.; Kemer, O.E.; Coskun, C. The optical coherence tomography angiography findings of rheumatoid arthritis patients taking hydroxychloroquine. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2018, 29, 532–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conigliaro, P.; Cesareo, M.; Chimenti, M.S.; Triggianese, P.; Canofari, C.; Aloe, G.; Nucci, C.; Perricone, R. Evaluation of retinal microvascular density in patients affected by systemic lupus erythematosus: An optical coherence tomography angiography study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2019, 78, 287–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goker, Y.S.; Atılgan, C.U.; Tekin, K.; Kızıltoprak, H.; Yetkin, E.; Karahan, N.Y.; Koc, M.; Kosekahya, P. The Validity of Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography as a Screening Test for the Early Detection of Retinal Changes in Patients with Hydroxychloroquine Therapy. Curr. Eye Res. 2018, 44, 311–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bulut, M.; Akıdan, M.; Gözkaya, O.; Erol, M.K.; Cengiz, A.; Çay, H.F. Optical coherence tomography angiography for screening of hydroxychloroquine-induced retinal alterations. Graefe’s Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2018, 256, 2075–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmor, M.F.; Kellner, U.; Lai, T.Y.Y.; Melles, R.B.; Mieler, W.F. Recommendations on Screening for Chloroquine and Hydroxychloroquine Retinopathy (2016 Revision). Ophthalmology 2016, 123, 1386–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marmor, M.F.; Ahn, S.J.; Ehlers, J.P.; Melles, R.B.; Mieler, W.F.; Sarraf, D.; Yusuf, I.H. Special AAO Report: Recommendations on Screening for Hydroxychloroquine Retinopathy (2025 Revision). Ophthalmology, 2025; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Yusuf, I.H.; Latheef, F.; Ardern-Jones, M.; Lotery, A.J. New recommendations for retinal monitoring in hydroxychloroquine users: Baseline testing is no longer supported. Br. J. Dermatol. 2021, 185, 435–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, J.T.; Costenbader, K.H.; Desmarais, J.; Ginzler, E.M.; Fett, N.; Goodman, S.; O’Dell, J.R.; Schmajuk, G.; Werth, V.P.; Melles, R.B.; et al. American College of Rheumatology, American Academy of Dermatology, Rheumatologic Dermatology Society, and American Academy of Ophthalmology 2020 Joint Statement on Hydroxychloroquine Use With Respect to Retinal Toxicity. Arthritis Amp; Rheumatol. 2021, 73, 908–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guven, T.K.; Alexander, A.; Smith, G.T. Hydroxychloroquine retinopathy screening guidelines: A false positive. BMJ Case Rep. 2023, 16, e249052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, E.; Johnson, J.; Mazzulla, D. Highly Accelerated Onset of Hydroxychloroquine Macular Retinopathy. Ochsner J. 2017, 17, 280–283. [Google Scholar]

- Bel, L.H.; Adsuara, C.M.; Garfella, M.H.; Taulet, E.C. Toxicidad macular precoz tras 2 meses de tratamiento con hidroxicloroquina. Arch. Soc. Española Oftalmol. 2018, 93, e20–e21. [Google Scholar]

- Pasaoglu, I.; Onmez, F. Macular toxicity after short-term hydroxychloroquine therapy. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 67, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, Y.-Y.; Ma, Y.-C.; Cheng, C.-K. Unusual Presentation of Acute Hydroxychloroquine Retinopathy. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2022, 31, 1720–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohapatra, A.; Gupta, P.; Ratra, D. Accelerated hydroxychloroquine toxic retinopathy. Doc. Ophthalmol. 2023, 148, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, N.; Schaab, T.; Mirza, R.G. Advanced Pericentral Hydroxychloroquine Retinopathy in an Asian Woman. J. Vitreoretin. Dis. 2019, 4, 148–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandit, S.A.; Nair, A.A.; Mehta, N.; Lee, G.D.; Freund, K.B.; Modi, Y.S. Delayed Detection of Predominantly Pericentral Hydroxychloroquine Toxicity in a Dominican Patient. J. Vitreoretin. Dis. 2021, 6, 324–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mack, H.G.; Fuzzard, D.R.W.; Symons, R.C.A.; Heriot, W.J. Asymmetric Hydroxychloroquine Macular Toxicity with Aphakic Fellow Eye. Retin. Cases Brief Rep. 2021, 15, 176–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallali, G.; Seyed, Z.; Maillard, A.-V.; Drine, K.; Lamour, L.; Faure, C.; Audo, I. Extreme Interocular Asymmetry in an Atypical Case of a Hydroxychloroquine-Related Retinopathy. Medicina 2022, 58, 967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeltsch, B.M.; Sarraf, D.; Madjdpour, D.; Hanson, J.V.M.; Pfiffner, F.K.; Koller, S.; Berger, W.; Barthelmes, D.; Al-Sheikh, M. Rapid Onset Hydroxychloroquine Toxicity. Retin. Cases Brief Rep. 2023, 18, 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozawa, H.; Ueno, S.; Ohno-Tanaka, A.; Sakai, T.; Hashiguchi, M.; Shimizu, M.; Fujinami, K.; Ahn, S.J.; Kondo, M.; Browning, D.J.; et al. Ocular findings in Japanese patients with hydroxychloroquine retinopathy developing within 3 years of treatment. Jpn. J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 65, 472–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.M.; Kwon, H.Y.; Ahn, S.J. Atypical Presentations of Hydroxychloroquine Retinopathy: A Case Series Study. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 3411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.Y.; Vinayagamoorthy, N.; Han, K.; Kwok, S.K.; Ju, J.H.; Park, K.S.; Jung, S.; Park, S.; Chung, Y.; Park, S. Association of Polymorphisms of Cytochrome P450 2D6 With Blood Hydroxychloroquine Levels in Patients With Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015, 68, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petri, M.; Elkhalifa, M.; Li, J.; Magder, L.S.; Goldman, D.W. Hydroxychloroquine Blood Levels Predict Hydroxychloroquine Retinopathy. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020, 72, 448–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, E.; Robertson, M.; Kam, S.; Penwarden, A.; Riga, P.; Davies, N. Correction: Prevalence of hydroxychloroquine retinopathy using 2018 Royal College of Ophthalmologists diagnostic criteria. Eye 2020, 35, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadhaniya, N.V.; Sood, I.; Patil, A.; Mallaiah, U.; Upadhyaya, S.; Handa, R.; Gupta, S.J. Screening for Hydroxychloroquine Retinal Toxicity in Indian Patients. JCR: J. Clin. Rheumatol. 2020, 27, e395–e398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browning, D.J.; Lee, C. Somatotype, the risk of hydroxychloroquine retinopathy, and safe daily dosing guidelines. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2018, 12, 811–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zirtiloglu, S.; Alikma, M.S.; Acar, O.P.A.; Güven, F.; Icacan, O.C.; Yigit, F.U. Evaluation of the Optic Nerve Head Using Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography in Systemic Sclerosis Patients. Klin. Monatsblätter Augenheilkd. 2022, 240, 1277–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melles, R.B.; Marmor, M.F. Pericentral Retinopathy and Racial Differences in Hydroxychloroquine Toxicity. Ophthalmology 2015, 122, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousquet, E.; Santina, A.; Somisetty, S.; Morales, V.R.; Holland, G.N.; Sarraf, D. Hydroxychloroquine retinopathy in a 23-year-old male. Retin. Cases Brief Rep. 2024, 20, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Huang, Y.; Ye, Q.; Shang, F.; Ming, M.; Xu, H.; Li, Z. Low-dose oral hydroxychloroquine led to impaired vision in a child with renal failure: Case report and literature review. Medicine 2021, 100, e24919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlAhmed, O.; Way, A.; Akoghlanian, S.; Barbar-Smiley, F.; Lemle, S.; MacDonald, D.; Frost, E.; Wise, K.; Lee, L.; Ardoin, S.P.; et al. Improving eye screening practice among pediatric rheumatology patients receiving hydroxychloroquine. Lupus 2020, 30, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donica, V.C.; Donica, A.L.; Pavel, I.A.; Danielescu, C.; Alexa, A.I.; Bogdănici, C.M. Variabilities in Retinal Hemodynamics Across the Menstrual Cycle in Healthy Women Identified Using Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography. Life 2024, 15, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheu, S.-J.; Chang, C.-Y. Macular edema might be a rare presentation of hydroxychloroquine-induced retinal toxicity. Taiwan J. Ophthalmol. 2017, 7, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhusseiny, A.M.; Relhan, N.; Smiddy, W.E. Docetaxel-induced maculopathy possibly potentiated by concurrent hydroxychloroquine use. Am. J. Ophthalmol. Case Rep. 2019, 16, 100560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, E.H.; Ahn, S.J.; Lim, H.W.; Lee, B.R. The effect of oral acetazolamide on cystoid macular edema in hydroxychloroquine retinopathy: A case report. BMC Ophthalmol. 2017, 17, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathai, M.; Zeleny, A.; Jacobsen, B.H.; Garfinkel, R.A.; Katira, R.; Fein, J.G. Intravitreal Dexamethasone for the Treatment of Macular Edema Secondary to Hydroxychloroquine Toxicity. Retin. Cases Brief Rep. 2022, 18, 346–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Shi, W.; Yang, Y. The efficacy and safety of hydroxychloroquine for COVID-19 prophylaxis and clinical assessment: An updated meta-analysis of randomized trials. J. Thorac. Dis. 2024, 16, 2983–2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nti, A.A.; Serrano, L.W.; Sandhu, H.S.; Uyhazi, K.E.; Edelstein, I.D.; Zhou, E.J.; Bowman, S.; Song, D.; Gangadhar, T.C.; Schuchter, L.M.; et al. Frequent Subclinical Macular Changes in Combined Braf/Mek Inhibition with High-Dose Hydroxychloroquine as Treatment for Advanced Metastatic Braf Mutant Melanoma: Preliminary Results From a Phase I/II Clinical Treatment Trial. Retina 2019, 39, 502–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielescu, C.; Dabija, M.G.; Nedelcu, A.H.; Lupu, V.V.; Lupu, A.; Ioniuc, I.; Gîlcă-Blanariu, G.-E.; Donica, V.-C.; Anton, M.-L.; Musat, O. Automated Retinal Vessel Analysis Based on Fundus Photographs as a Predictor for Non-Ophthalmic Diseases—Evolution and Perspectives. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 14, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author | Participants | Medication Duration (Years) | Cumulative HCQ Dose (g) | Mean Daily Dose to Real Body Weight (mg/kg) | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Farvardin, 2024 [11] | 47 HCQ patients, 25 controls | 5.1 ± 5.2 | 301 ± 365 | / |

|

| Salameh, 2024 [12] | 40 HCQ eyes vs. 40 controls | 8.56 ± 4.4 years | 1215.45 ± 654.77 | / |

|

| Montesel, 2024 [9] | 35 HCQ eyes, 30 controls | 8 + 5.3 | 704.3 ± 522.5 | / |

|

| Garg, 2024 [13] | 10 HCQ patients and 12 controls | 14.3 ± 4.1 | 1723.6 ± 574.2 | / |

|

| Kitay, 2023 [14] | G1: 34 HCQ eyes with DLDS and G2: 32 HCQ eyes without DLDs | G1: 8.20 ± 5.44 G2: 6.10 ± 4.89 | G1: 608.60 ± 361.48, G2: 646.16 ± 491.62 | / |

|

| Melles, 2022 [10] | 301 HCQ patients G1: 219 with stable thickness G2: 82 with rapid thinning | G1: 14.7 ± 5.4 G2: 15.4 ± 5.4 | / | G1: 3.4 ± 1.1 G2: 4.2 ± 1.2 |

|

| Tarassoly, 2022 [15] | 53 HCQ eyes, 21 controls | 11 ± 4 | 1114 ± 481 | / |

|

| Borrelli, 2021 [16] | G1: 63 HCQ eyes G1a: 46 eyes patients without HCR G1b: 17 HCR G2: 30 controls | G1: 8.4 G1a: 7.6 G1b: 10.5 | G1: 782.8 G1a: 704.3 G1b: 973.4 | / |

|

| Sallam, 2021 [17] | G1: 60 HCQ eyes G1a: 10 with normal VA G1b: 50 with decreased VA G2: 50 controls | G1a: 5.6 G1b: 8.3 | G1a: 408.8 G1b: 1214.7 | / |

|

| Manoj, 2021 [18] | 110 patients | 7.7 ± 2.5 | 840 ± 305.6 g | 14.8 ± 5.4 |

|

| Kim 2021 [19] | 1723 HCQ eyes | 15.9 ± 6.6 | 1436.7 ± 529 | 5.15 ± 1.53 |

|

| Hasan, 2020 [20] | 100 HCQ patients > 5 y HCQ, 70 controls | 6.3 | / | / |

|

| Pandey, 2020 [21] | G1: 167 HCQ patients G1a: 9 HCR patients | G1a: 4.5 ± 2.96 | G1a: 515.1 ± 360.7 | G1a: 6.09 ± 1.79 |

|

| Dias-Santos, 2020 [22] | G1a: 18 HCR patients G1b: 143 without HCR | G1a: 14.7 G1b: 6.9 | G1a: 2130.1 G1b: 939 | / |

|

| Casado, 2020 [23] | 42 HCR eyes, 72 controls | 3.44 | / | / |

|

| Souza Cabral, 2019 [24] | G1: 217 patients with antimalaria treatment G1a: 9 HCR patients | G1a: 10.4 | / | / |

|

| Trenkic Bozinovic, 2019 [25] | G1: 26 HCQ eyes with no visible changes in the macula G2: 30 HCR eyes | 6.11 ± 5.85 years | 557.9 ± 534.7 | / |

|

| Cakir, 2019 [26] | G1a: 44 patients > 5 y HCQ G1b: 30 patients < 5 y HCQ G2: 45 controls | G1a: 1.8 ± 1.1 G1b: 9.6 ± 5.0 | G1a: 231.28 ± 215.9 G1b: 794.62 ± 473.2 | / |

|

| Garrity, 2019 [27] | 17 HCQ eyes | 11.0 ± 6.5 | 1611.4 ± 886.2 | 5.87 ± 1.10 |

|

| Allahdina, 2019 [28] | 44 eyes with HCR | 13.83 ± 7.08 | / | 5.9 ± 1.8 |

|

| Pham, 2019 [29] | 13 patients with HCR | 13.31 ± 5.82 | 2026.7 ± 1078.1 | 6.55 ± 2.67 |

|

| Ruberto, 2018 [30] | 33 patients with rheumatic diseases, 28 controls | 10.39 ± 8.28 | 594.5 ± 481.2 | 3.9 ± 2.6 |

|

| Allahdina, 2018 [31] | G1: 57 HCQ patients G1a: 19 HCR patients G1b: 38 without HCR | G1a: 15.3 ± 7.1 G1b: 14.9 ± 8.3 | G1a: 1871 ± 927 G1b: 2036 ± 1141 | G1a: 5.61 ± 2.03 G1b: 5.51 ± 1.41 |

|

| Ahn, 2018 [32] | G1: 33 patients with HCR G2: 148 HCQ patients without HCR G3: 81 controls | G1: 14.2 ± 4.2 G2: 11.3 ± 5 | G1: 1446.9 ± 616.5 G2: 1000.7 ± 526.9 | G1: 5.5 ± 1.6 G2: 4.4 ± 1.6 |

|

| Kim, 2017 [33] | G1: 123 HCQ patients G1a: 17 HCR patients | G1: 10.1 years G1a: 15.2 | G1: 1167.4 G1a: 1866.4 | G1: 6.4 G1a: 7.2 |

|

| Ahn, 2017 [34] | 48 eyes with HCR | 13.7 ± 4.5 years | 1482 ± 650 | 5.8 ± 1.9 |

|

| Eo, 2017 [35] | G1: 310 HCQ patients G1a: 9 HCR patients | G1: 6.0 ± 3.4 G1a: 9.1 ± 2.7 | G1: 625.5 ± 376.2 G1a: 952.0 ± 519.2 g | G1: 5.5 ± 1.8 G1a: 5.6 ± 2.6 |

|

| Author | Participants | Medication Duration (Years) | Cumulative HCQ Dose (g) | Mean Daily Dose to Real Body Weight (mg/kg) | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| He, 2024 [36] | 120 HCQ eyes | 6.4 ± 4.4 | 821.6 ± 630.3 | 5.9 ± 2.5 |

|

| Yucel Gencoglu, 2024 [37] | 61 HCQ patients and 44 controls | 7.0 ± 4.9 | / | 2.81 ± 0.94 |

|

| Talcott, 2024 [38] | G1a: 38 HCR eyes G1b: 45 HCQ eyes without HCR G2: 44 controls | G1a: 10.9 ± 5.1 G1b: 10.8 ± 3.3 | G1a: 1520.1 ± 765.3 G1b: 1493.7 ± 504.3 | G1a: 5.6 ± 1.8 G1b: 5.1 ± 1.4 |

|

| Alieldin, 2022 [39] | 344 patients for baseline screening, 566 HCQ patients with risk factors | 9 ± 5 | / | / |

|

| Kim, 2022 [40] | 146 HCQ eyes | 14.7 ± 7.1 | 1340.4 ± 707.3 | 4.9 ± 1.4 |

|

| Kalra, 2022 [41] | 388 HCQ eyes evaluated at 2 visits (V1 and V2) | V1: 5.8 ± 3.7 V2: 8.8 ± 3.9 | V1: 780 ± 556 V2: 1186 ± 592 | 4.9 ± 1.5 |

|

| Jayakar, 2022 [42] | 84 HCQ patients, G1a: 54 without HCR, G1b: 30 with HCR | G1a: 14.5 ± 7.4 G1b: 14.22 ± 6.57 | / | / |

|

| Dabit, 2022 [43] | G1: 634 HCQ patients G1a: 11 HCR patients | / | G1: 472 G1a: 540 | G1: 4.5 G1a: 5.7 |

|

| Ahn, 2021 [44] | 80 HCR eyes | 13.3 ± 5.2 | 1307.1 ± 437.3 | 5.0 ± 1.8 |

|

| Jauregui, 2020 [45] | 88 HCQ eyes | 8 ± 6 | 994.75 ± 798.85 | 5.19 ± 1.68 |

|

| Gobbett, 2021 [46] | 678 HCQ patients, 333 patients at risk | / | / | / |

|

| Browning, 2019 [47] | 64 HCQ patients | 9.8 | 1431 | 4.6 |

|

| Ugwuegbu, 2019 [48] | 14 HCR eyes, 14 controls | 20.6 ± 15.0 | / | 5.5 ± 1.6 |

|

| Arndt, 2018 [49] | G1: 354 HCQ patients G1a: 17 HCR patients | G1a: 6.46 ± 6.47 | G1a: 870.2 ± 969.5 | G1a: 5.36 ± 1.78 |

|

| Author | Participants | Medication Duration (Years) | Cumulative HCQ Dose (g) | Mean Daily Dose to Real Body Weight (mg/kg) | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jung, 2024 [50] | G1: 76 HCQ eyes, G1a: 38 eyes < 5 y HCQ, G1b: 38 eyes > 5 y HCQ, G2: 36 controls | G1: 8.60 ± 6.09, G1a: 4.05 ± 1.14 G1b: 13.42 ± 5.48 | / | / |

|

| Sonalcan, 2024 [51] | G1: 60 HCQ eyes > 5 y HCQ, G2: 62 HCQ eyes < 5 y HCQ, 28 patients with RA, SLE, SJS | G1: 8.77 ± 3.01 G2: 2.67 ± 1.09 | G1: 639.97 ± 217.52 G2: 194.98 ± 79.57 | / |

|

| Mimier Janczak, 2023 [52] | 57 SLE eyes, 56 controls | 8.48 ± 7.50 | 391.23 ± 425.52 | / |

|

| Agcayazi, 2023 [53] | 80 HCQ eyes, 40 controls | 6.4 ± 5.1 | 504.88 ± 387.4 | / |

|

| Kim, 2023 [54] | G1: 66 HCQ patients without HCR G2: 66 HCR patients with retinopathy | G1: 9.4 ± 7.7 G2: 15.6 ± 6.9 | G1: 797.2 ± 685.5 G2: 1351.7 ± 701.7 | G1: 4.5 ± 1.3 G2: 4.7 ± 1.4 |

|

| Mondal, 2022 [55] | 19 HCQ patients and 37 controls | 8.36 ± 7.9 | 16.04 ± 16.72 | 5.04 ± 1.36 |

|

| Membreno, 2023 [56] | 85 HCQ patients, G0: 55 with no signs of toxicity, G1–4: 30 grouped by HCR severity. | G0: 14.5 ± 7.4, G1: 16.7 ± 9.4 G2: 12.2 ± 3.9 G3: 12.0 ± 5.4 G4: 16.7 ± 7.7 | / | G0: 5.1 ± 1.6 G1: 4.8 ± 1.8 G2: 5.5 ± 2.1 G3: 6.0 ± 1.5 G4: 6.5 ± 1.8 |

|

| Aydin Kurna, 2022 [57] | G1: 81 patients > 6 months HCQ, G1a > 60 months, G1b < 60 months, G2: 34 rheumatological patients without HCQ, G3: 30 controls | G1a: 8.41 ± 3.91 G1b: 4.17 ± 1.2 | G1a: 843.37 ± 489.38 G1b: 208.63 ± 135.01 | / |

|

| Godinho, 2021 [58] | 144 HCQ eyes evaluated at 2 visits (V1 and V2) | V1: 4 V2: 7.19 ± 1.55 | V1: 730 V2: 1144.3 ± 229.3 | 4.89 ± 2.01 |

|

| Martin-Iglesias, 2019 [59] | 195 HCQ eyes at 2 visits (V1 and V2) | V1: 5.75 V2: 11.08 | V1: 398.5 V2: 774 | V1: 3.22 V2: 3.12 |

|

| Gil, 2019 [60] | G1: 93 HCQ eyes G1a: 25 eyes < 5 y HCQ G1b: 68 eyes > 5 y HCQ | G1: 8.39 ± 5.09 G1a: 2.96 ± 1.17 G1b: 10.38 ± 4.48 | G1: 1020.2 ± 675 G1a: 382.08 ± 167.71 G1b: 1254.81 ± 638.55 | G1: 5.09 ± 1.53 G1a: 5.31 ± 1.21 G1b: 5.01 ± 1.63 |

|

| Conigliaro, 2018 [61] | G1: 30 SLE, HCQ patients, G2: 24 SS HCQ patients, G3: 76 controls | G1: 52.3 ± 55.5 G2: 49.1 ± 73.1 | G1: 549.7 ± 479.8 G2: 555.3 ± 862.2 | / |

|

| Lee, 2018 [62] | G1: 77 HCQ patients G2: 20 controls | 5.3 ± 3.2 | 528.1 ± 344.1 | 5.64 ± 1.8 |

|

| Bulut, 2017 [63] | G1: 92 HCQ eyes G2: 80 controls | 4.84 ± 3.19 | 543.6 ± 340.8 | / |

|

| Telek, 2017 [64] | G1: 35 eyes of SLE patients with HCQ G2: 40 eyes of RA patients with HCQ G3: 20 controls | G1: 0.58 ± 0.43 G2: 0.63 ± 0.5 | / | / |

|

| Kan, 2017 [65] | 90 HCQ eyes > 5 y treatment, 90 controls | 6.66 | / | / |

|

| Author | Participants | Medication Duration (Years) | Cumulative HCQ Dose (g) | Mean Daily Dose to Real Body Weight (mg/kg) | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arias-Peso, 2024 [66] | G1: 32 eyes from <5 y HCQ G2: 44 eyes from >5 y HCQ G3: 46 control | G1: 2.84 ± 1.66 G2: 8.74 ± 4.15 | G1: 243.79 ± 162.17 G2: 673.03 ± 362.47 | G1: 3.61 ± 1.35 G2: 3.29 ± 1.65 |

|

| Hasan, 2023 [67] | 276 HCQ eyes | 2.81 | 215.6 | 4.5 ± 1.6 |

|

| Halouani, 2023 [68] | G1: 48 HCQ eyes G1a: 22 eyes mild HCR G1b: 26 eyes HCR G2: 34 controls | G1a: 4.65 ± 3.27 G1b: 13.22 ± 8.86 | G1a: 592.4 ± 481.27 G1b: 1825 ± 1026.98 | G1a: 4.95 ± 1.31 G1b: 6.35 ± 1.94 |

|

| Ru, 2023 [69] | 45 JSLE HCQ patients, 50 controls | 2.25 | 188.5 | / |

|

| Kukan, 2022 [70] | G1: 16 HCQ patients with DLD G2: 16 HCQ patients without DLD | G1: 7.4 G2: 5.3 | G1: 567.6 G2: 486.6 | G1: 3.8 G2: 4.3 |

|

| Polat, 2022 [71] | G1a: 29 patients < 5 y HCQ; G1b: 20 patients > 5 y HCQ; G2: 39 controls | G1a: 2.01 ± 1.23 G1b: 8.27 ± 4.02 | G1a: 248.4 ± 181.6 G1b: 896 ± 480.7 | / |

|

| Ahn, 2019 [72] | 40 HCR eyes | 12.8 ± 3.4 | 1.430 ± 449 | 6.1 ± 1.4 |

|

| Ahn, 2017 [73] | 146 HCQ patients, G1: with HCR, G2: without HCR | G1: 12.5 ± 3.7 G2: 7.9 ± 5.5 | G1: 1372 ± 450 G2: 780 ± 580 | G1: 6.2 ± 1.5 G2: 5.1 ± 1.7 |

|

| Karti, 2017 [74] | G1: 30 RA patients G2: 30 controls | / | / | / |

|

| Author | Participants | Medication Duration (Years) | Cumulative HCQ Dose (g) | Mean Daily Dose to Real Body Weight (mg/kg) | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Li, 2025 [76] | 40 HCQ eyes, 40 controls | 6.35 ± 5.37 | 403.32 ± 220.21 | 4.68 ± 2.10 |

|

| Bartol-Puyal, 2024 [77] | G1a: 41 HCQ eyes < 10 y SLE, G1b: 31 HCQ eyes > 10 y SLE, G2: 45 controls | G1a: 5.06 ± 2.91 G1b: 7.46 ± 3.88 | G1a: 407.50 ± 270.58 G1b: 560.50 ± 334 | G1a: 3.46 ± 1.38 G1b: 3.34 ± 0.92 |

|

| Araujo, 2024 [78] | 132 HCQ eyes | 5 | 396 | 3.5 |

|

| Leclaire, 2024 [79] | 24 HCQ eyes | 7.2 | 856.2 | / |

|

| Zhao, 2024 [80] | 43 HCQ patients | 3.75 | 384 | 5.66 ± 1.66 |

|

| Liu, 2024 [81] | 135 HCQ patients | 4 | / | 4.8 |

|

| Vasilijevic, 2023 [82] | G1: 31 patients with autoimmune disorders; G2: 36 HCQ patients < 5 y; G3: 29 HCQ patients > 5 y. | G2: 2.92 ± 1.53 G3: 10.59 ± 4.63 | / | / |

|

| Esser, 2023 [83] | G1a: 21 HCQ eyes > 5 y, G1b: 9 HCQ eyes < 5 y, 30 controls | G1a: 9.42 ± 4.62 G1b: 3.2 ± 1.69 | G1a: 937 ± 599 G1b: 350 ± 242 | / |

|

| Liu, 2023 [84] | G1: 10 RA patients without CQ G2: 10 RA CQ patients G3: 10 controls | 8.4 ± 1.9 | / | / |

|

| Yu, 2023 [85] | G1: 12 SJS patients without HCQ G2: 12 HCQ patients G3: 12 controls | 5.5 ± 0.8 | / | / |

|

| Subasi, 2022 [86] | G1a: 44 SLE eyes > 5 y HCQ G1b: 16 SLE eyes < 5 y HCQ G2: 60 controls | / | G1a: 901.22 ± 445.44 G1b: 368.43 ± 195.66 | / |

|

| Halouani, 2022 [87] | G1: 76 HCQ eyes G1a: 62 HCQ eyes without HCR G1b: 14 HCR HCQ eyes G2: 60 controls | G1a: 9.90 ± 5.38 G1b: 15.85 ± 9.04 | G1a: 862.67 ± 592.72 G1b: 2294.29 ± 1274.63 | G1a: 5.56 ± 1.09 G1b: 5.75 ± 0.77 |

|

| Forte, 2021 [88] | 20 HCQ eyes, 36 controls | 10.03 ± 3.25 | 937.59 ± 332.37 | 4.46 ± 1.47 |

|

| Akhlaghi, 2021 [89] | 61 HCQ patients (40 eyes had abnormal mfERG and 21 had normal mfERG) | normal mfERG 13.23 +/− 5.83 years, abnormal mfERG 13.15 +/− 5.63 | normal mfERG- 978.20 +/− 523.20, abnormal mfERG 1034.77 +/− 590.09 | / |

|

| Cinar, 2021 [90] | 28 HCQ eyes, 28 controls | 5.25 ± 0.93 | 593.714 ± 450 | / |

|

| Tarakcioglu, 2020 [91] | G1: 70 HCQ eyes G1a: 41 eyes > 5 y HCQ G1b: 29 eyes < 5 y HCQ G2: 32 control eyes | G1: 6.11 ± 3.71 G1a: 2.47 ± 1.2 G1b: 8.52 ± 2.7 | / | / |

|

| Lenfant, 2020 [92] | G1: 23 HCR patients G2: 547 HCQ patients without HCR | G1: 16.2 G2: 6.6 | G1: 2338 G2: 884 | / |

|

| Mihailovic, 2020 [93] | 19 HCQ eyes without retinopathy; 19 healthy controls | 5.76 ± 5.18 | 819 ± 773 | / |

|

| Ozek, 2019 [94] | G1: 24 eyes > 5 y HCQ G2: 16 eyes < 5 y HCQ G3: 20 controls | G1: 123.9 ± 21.5 G2: 22.81 ± 10.5 | G1: 520.34 ± 112.71 G2: 330.12 ± 138.56 | / |

|

| Conigliaro, 2019 [95] | 52 HCQ eyes, 40 controls | 15.1 ± 7.7 | 738.8 ± 486.8 | / |

|

| Goker, 2019 [96] | 40 HCQ eyes, 40 controls | 5.85 ± 0.84 | / | 3.08 |

|

| Bulut, 2018 [97] | G1: 30 HCQ eyes > 5 y G2: 30 HCQ eyes < 5 y | G1: 7.73 ± 3.57 G2: 1.68 ± 1.36 | G1: 746.73 ± 446.52 G2: 137.67 ± 104.56 | G1: 3.60 ± 1.03 G2: 3.50 ± 0.85 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Donica, A.L.; Donica, V.C.; Russu, M.; Lăpuște, V.; Pomîrleanu, C.; Bogdănici, C.M.; Alexa, A.I.; Sandu, C.A.; Bilha, I.M.; Ancuța, C. Optical Coherence Tomography and Angiography in Hydroxychloroquine Retinopathy: A Narrative Review. Diagnostics 2026, 16, 463. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16030463

Donica AL, Donica VC, Russu M, Lăpuște V, Pomîrleanu C, Bogdănici CM, Alexa AI, Sandu CA, Bilha IM, Ancuța C. Optical Coherence Tomography and Angiography in Hydroxychloroquine Retinopathy: A Narrative Review. Diagnostics. 2026; 16(3):463. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16030463

Chicago/Turabian StyleDonica, Alexandra Lori, Vlad Constantin Donica, Mara Russu, Vladia Lăpuște, Cristina Pomîrleanu, Camelia Margareta Bogdănici, Anisia Iuliana Alexa, Călina Anda Sandu, Ioana Mădălina Bilha, and Codrina Ancuța. 2026. "Optical Coherence Tomography and Angiography in Hydroxychloroquine Retinopathy: A Narrative Review" Diagnostics 16, no. 3: 463. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16030463

APA StyleDonica, A. L., Donica, V. C., Russu, M., Lăpuște, V., Pomîrleanu, C., Bogdănici, C. M., Alexa, A. I., Sandu, C. A., Bilha, I. M., & Ancuța, C. (2026). Optical Coherence Tomography and Angiography in Hydroxychloroquine Retinopathy: A Narrative Review. Diagnostics, 16(3), 463. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16030463