Review of CNN-Based Approaches for Preprocessing, Segmentation and Classification of Knee Osteoarthritis

Abstract

1. Introduction

Significance of This Review

- (a)

- A comprehensive survey of relevant recent research studies is carried out, exploring various data sources, data preprocessing techniques, and DL architectures utilized.

- (b)

- A comparison of performance measures of the research studies is presented. Also, the effect of variations in methodologies on the performance measures such as accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, etc., is discussed.

- (c)

- Shortcomings of the considered research studies are analyzed, and promising future research directions are outlined.

- (d)

- The review of different preprocessing methods is added as shown in Table 1.

| Paper | Year | Preprocessing Techniques | Segmentation Techniques | DL Techniques | X-ray Dataset | MRI Dataset |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kokkotis et al. [7] | 2020 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Saini et al. [4] | 2021 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Yeoh et al. [8] | 2021 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Yick et al. [9] | 2022 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Lee et al. [10] | 2022 | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Ramazanian et al. [11] | 2023 | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Cigdem et al. [12] | 2023 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Zhao et al. [13] | 2024 | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Touahema et al. [14] | 2024 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Teoh et al. [15] | 2024 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Tariq et al. [16] | 2025 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| This Review | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

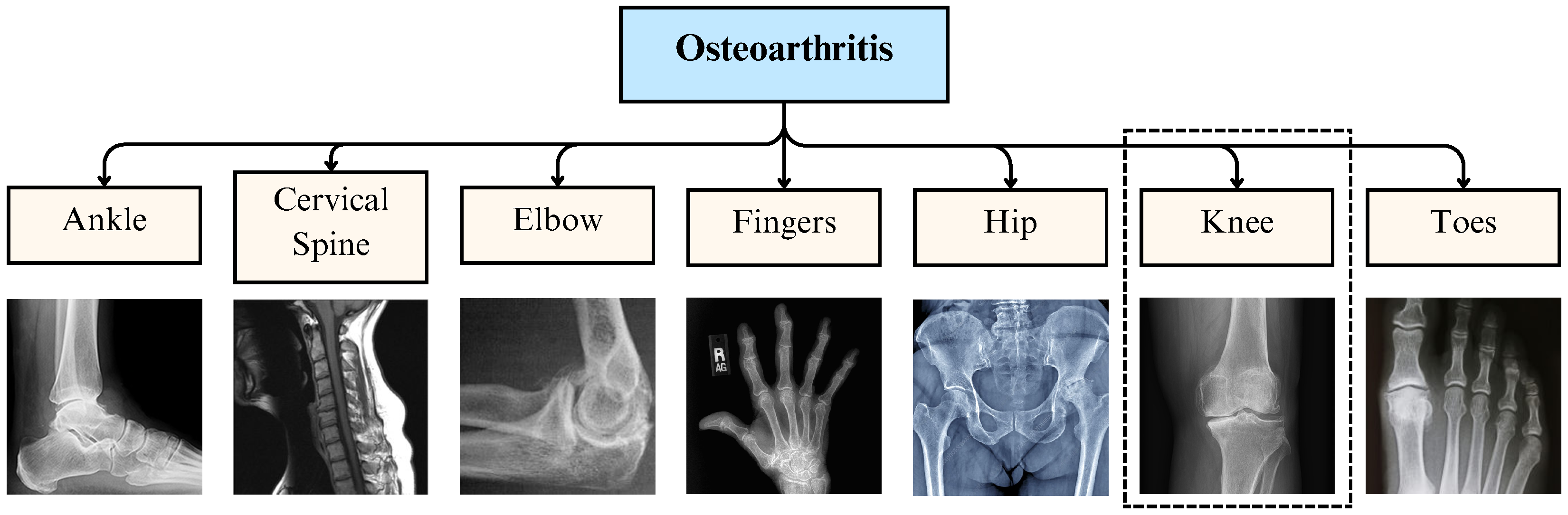

2. Osteoarthritis Overview

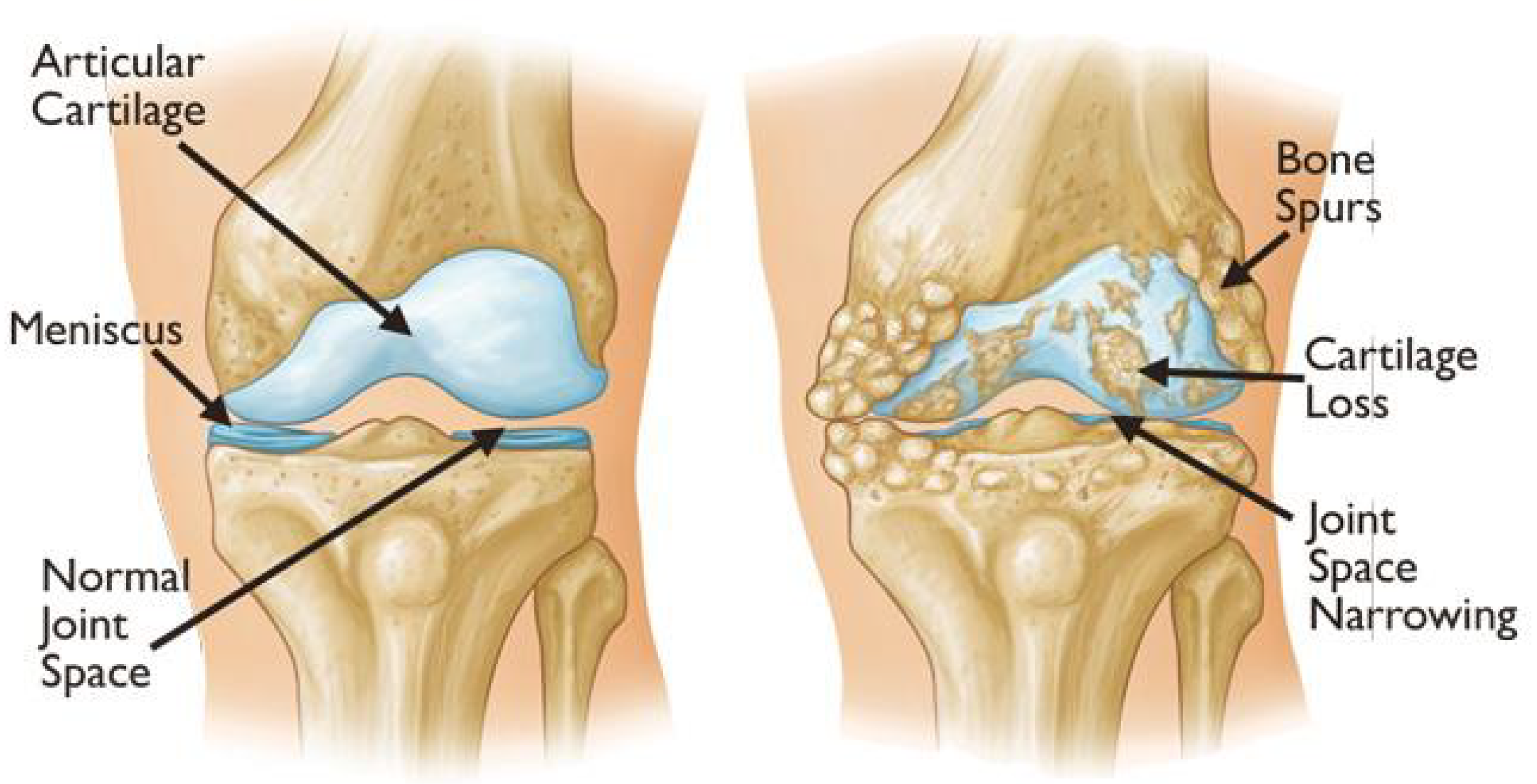

2.1. Knee Osteoarthritis

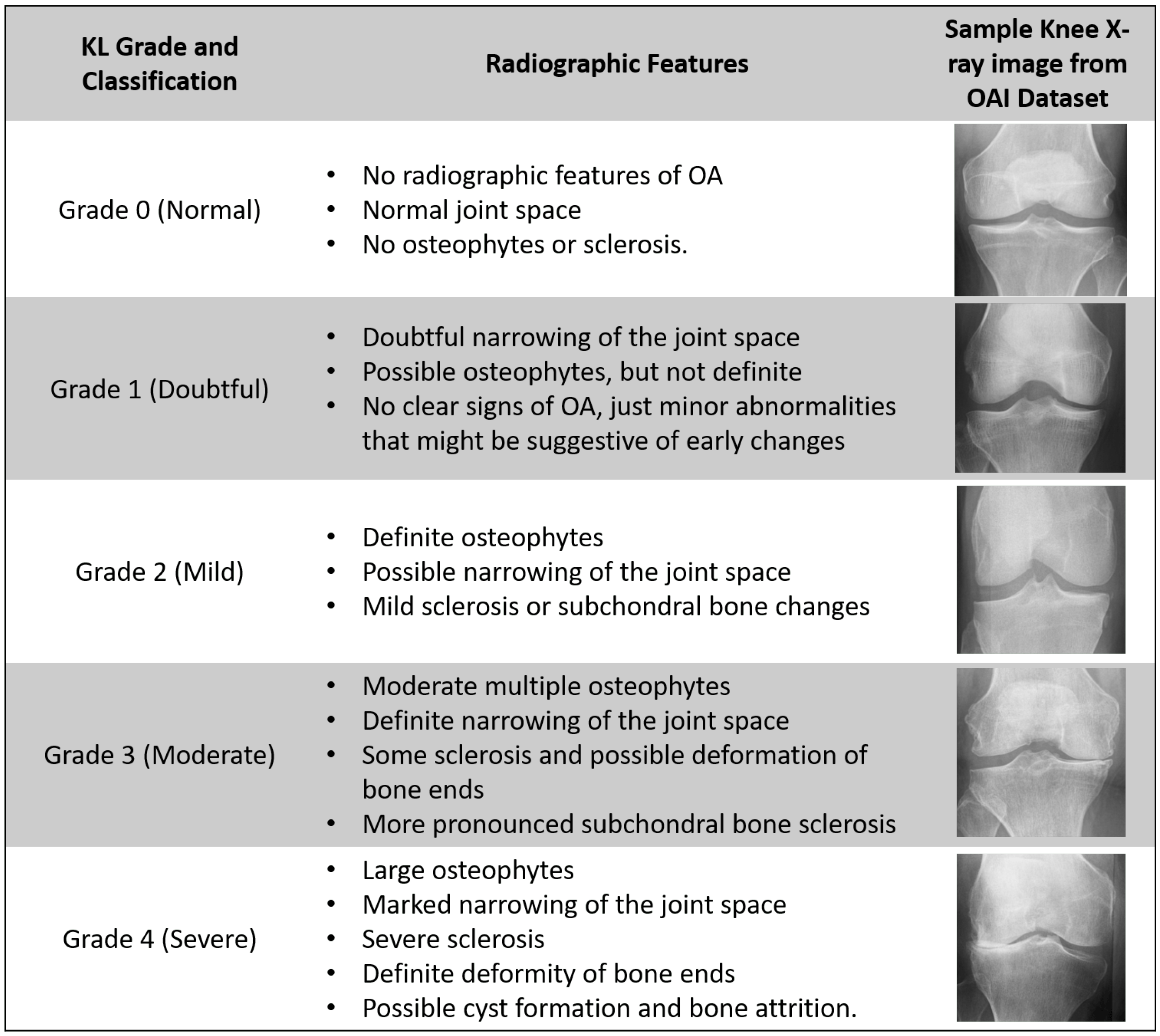

2.2. X-Ray Grading: Kellgren–Lawrence Scale

2.3. MRI-Based Grading Systems

- WORMS: This system is one of the most widely used MRI-based grading systems for KOA categorization. It evaluates multiple joint structures, including cartilage morphology, bone marrow lesions, menisci, synovitis, and joint effusion. Each structure is graded separately, providing a comprehensive assessment of disease progression. WORMS is particularly useful in longitudinal studies to monitor KOA development over time.

- BLOKS: BLOKS is another MRI-based grading system designed to assess KOA features related to disease progression. It focuses on specific biomarkers of joint degeneration, such as cartilage loss, bone marrow lesions, and synovitis/effusion. Compared to WORMS, BLOKS places greater emphasis on inflammation-related changes, making it useful for understanding the role of synovitis and effusion in KOA progression.

- MOAKS: MOAKS is an advanced grading system that builds upon WORMS and BLOKS, integrating their strengths while addressing some of their limitations. It provides detailed scoring for cartilage damage, bone marrow lesions, osteophytes, meniscal integrity, and synovitis. MOAKS offers improved inter-reader reliability and is widely used in clinical research to quantify structural changes in KOA.

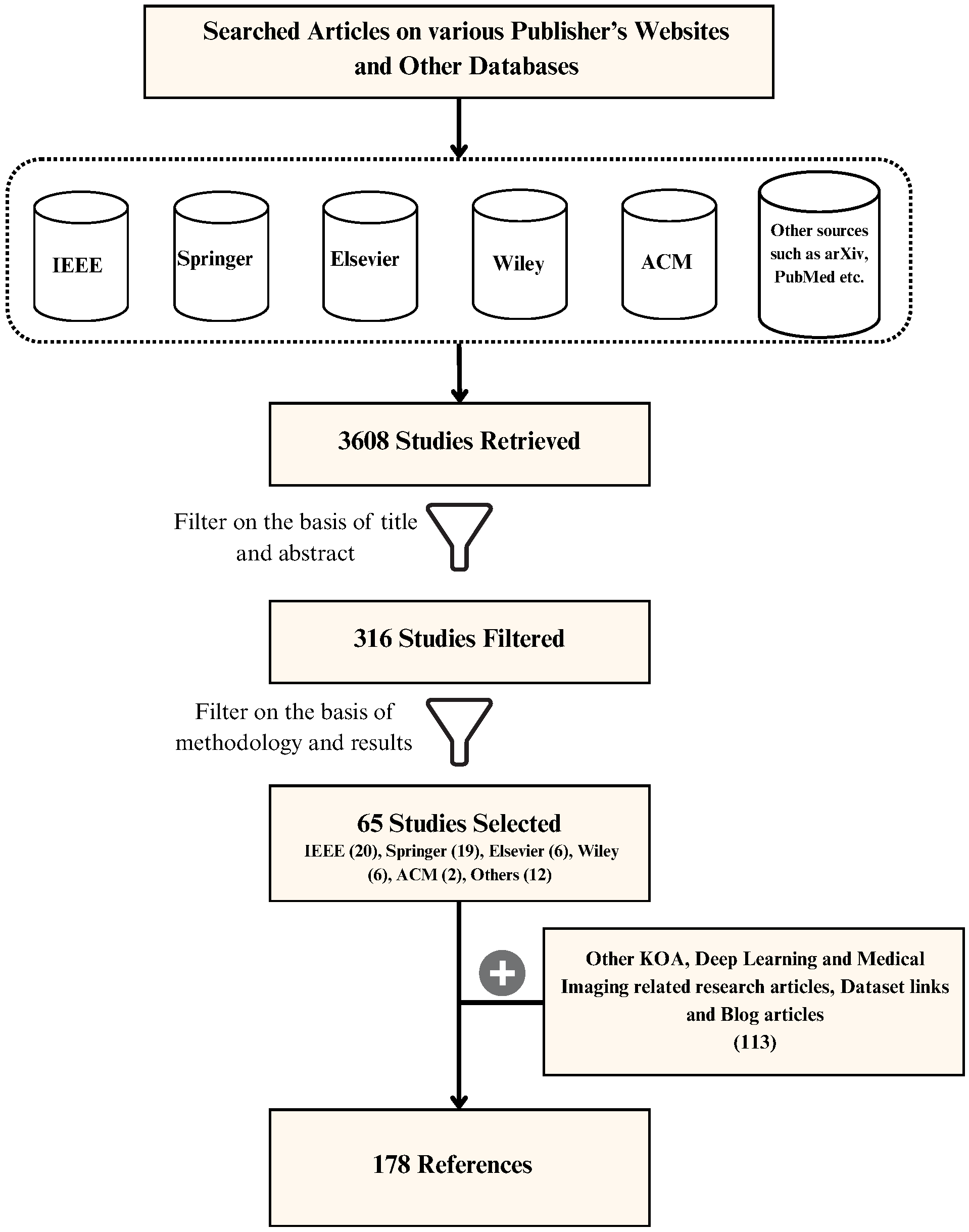

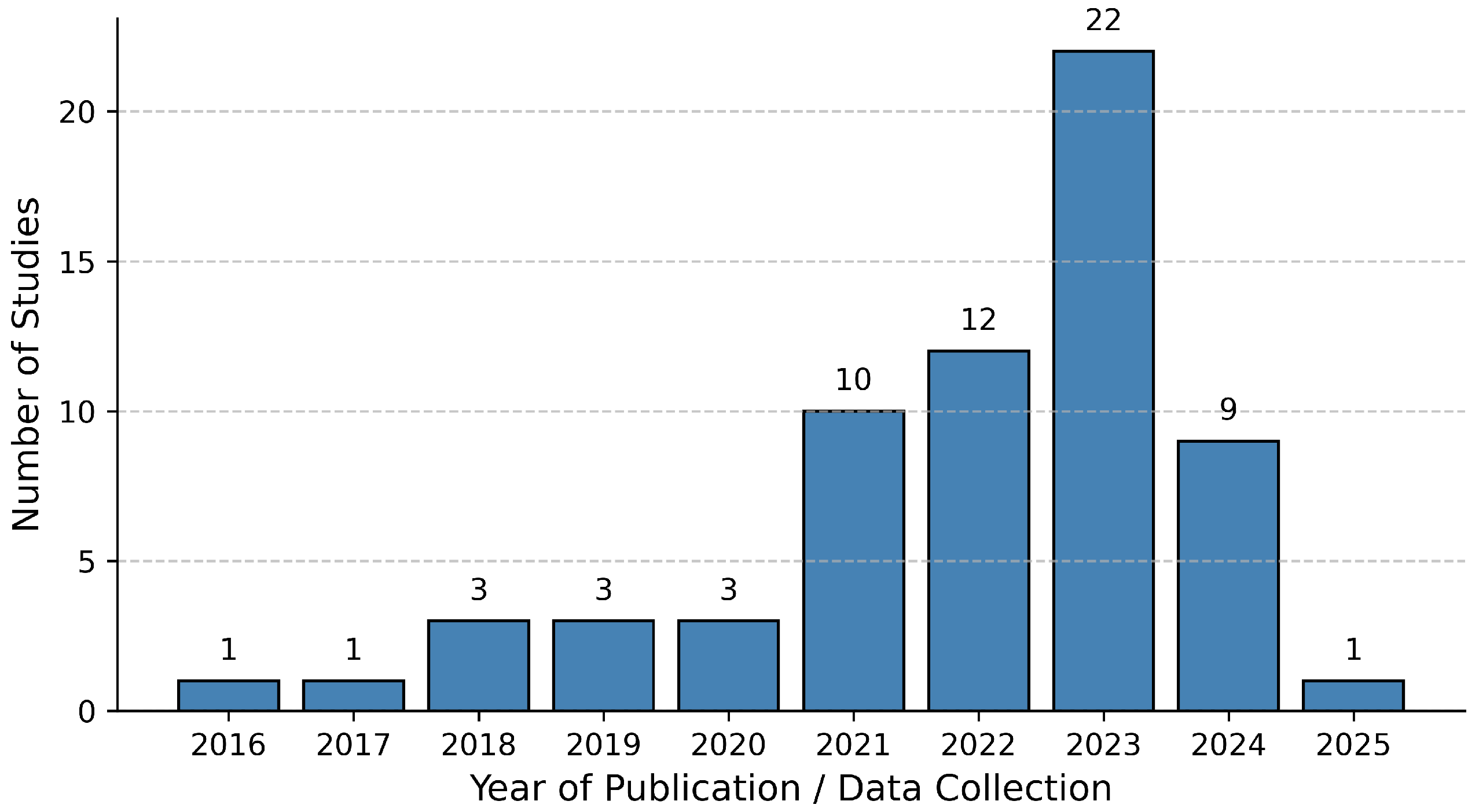

3. Literature Review Methodology

3.1. Sources of Literature

3.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- Study that preferably proposes a model developed using publicly available datasets such as Osteoarthritis Initiative (OAI) and Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study (MOST), etc.

- The research paper should be published in well-reputed journals.

- The paper included should be a recent study to keep this research up-to-date.

- Study proposing new methodologies to automate classification or reviewing existing literature or surveys on OA and KOA to keep this research as relevant as possible.

- Study using preprocessed enhanced images.

- Study that uses DL-based classification algorithms mostly using CNN-based architecture.

- The study thoroughly details their research and includes evaluation metrics like accuracy, precision, and recall for the proposed model.

- Articles that discuss only traditional image processing and ML techniques for KOA classification.

- Articles that use or propose DL architectures other than CNN-based ones, such as autoencoders, transformers, etc.

- KOA studies focusing on KOA progression based on the patient’s history.

- Studies using other grading methods except KL grading for X-ray images.

- Studies that use data modalities other than X-ray and MRI.

3.3. Study Selection Process

- Searching for papers using keywords such as “KOA”, “OA”, “KL Grade”, and “DL in Healthcare”, etc.

- Optimizing the search to include only the studies published by reputed journals.

- Going through the title and abstract of the study to decide its usefulness for the review.

- Analyzing all the findings and listing the ones that can be used in the review study.

- Noting the data sources and preprocessing techniques for the KOA classification studies.

- Listing all the architectures proposed, fine-tuning methods used, and results obtained by the studies.

- Mentioning the findings of the research in the appropriate section of this review and citing it.

- Comparing the performance measures of solutions proposed by different studies using some common evaluation metrics.

- Representing this survey visually in the form of appropriate figures, tables, graphs, and charts.

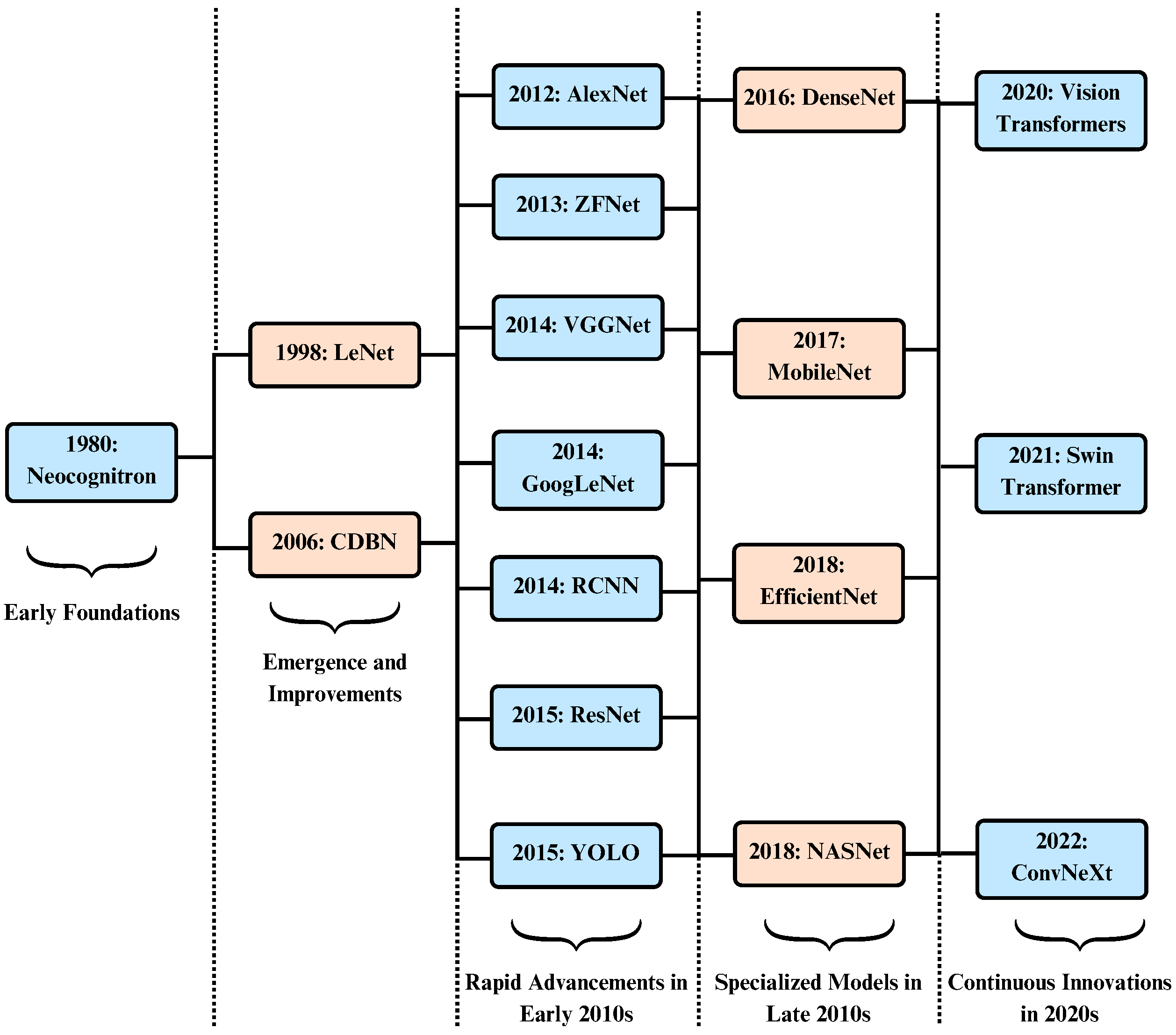

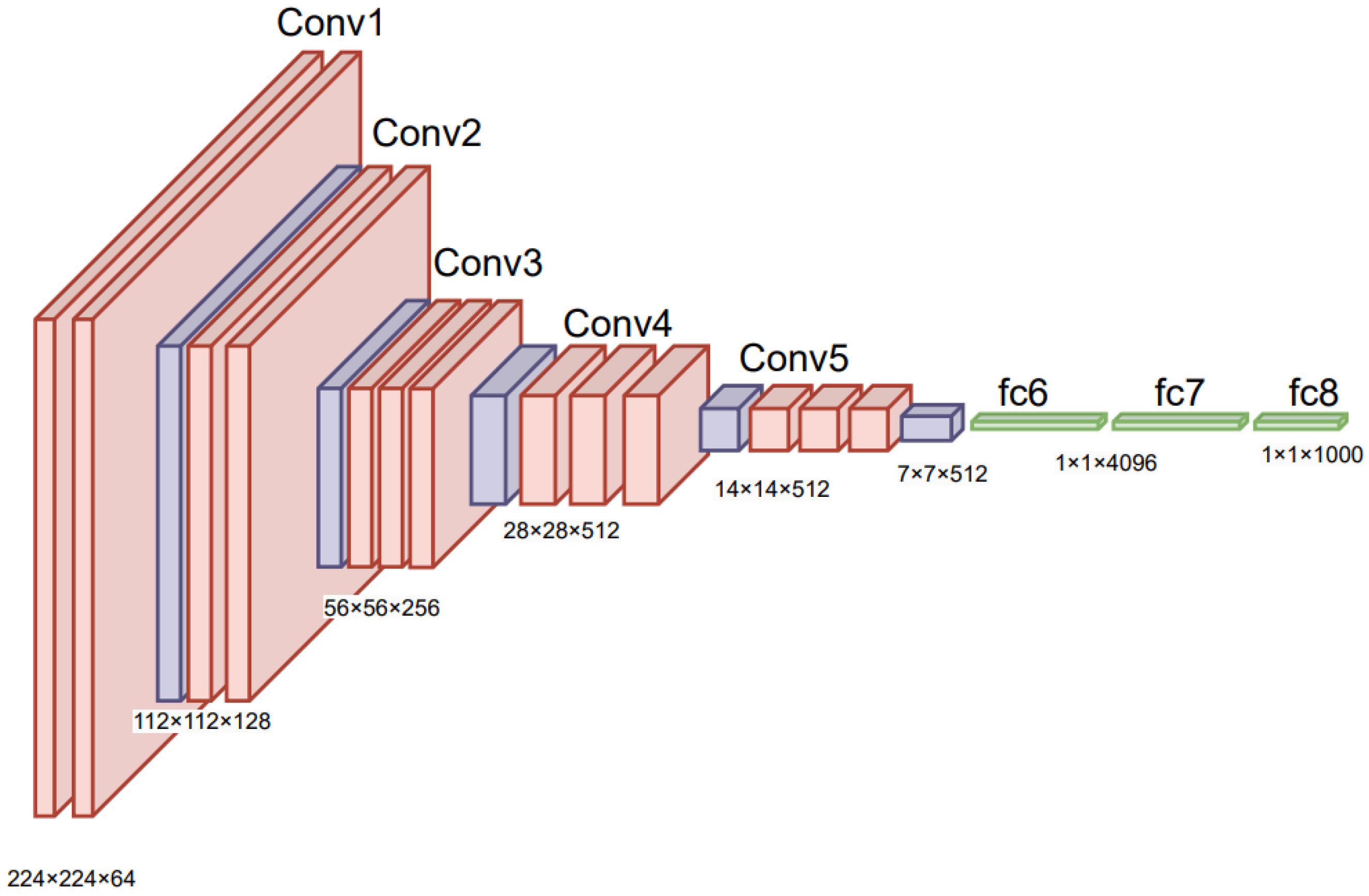

4. Deep Learning in Healthcare

Architectures and Applications

5. Datasets for KOA

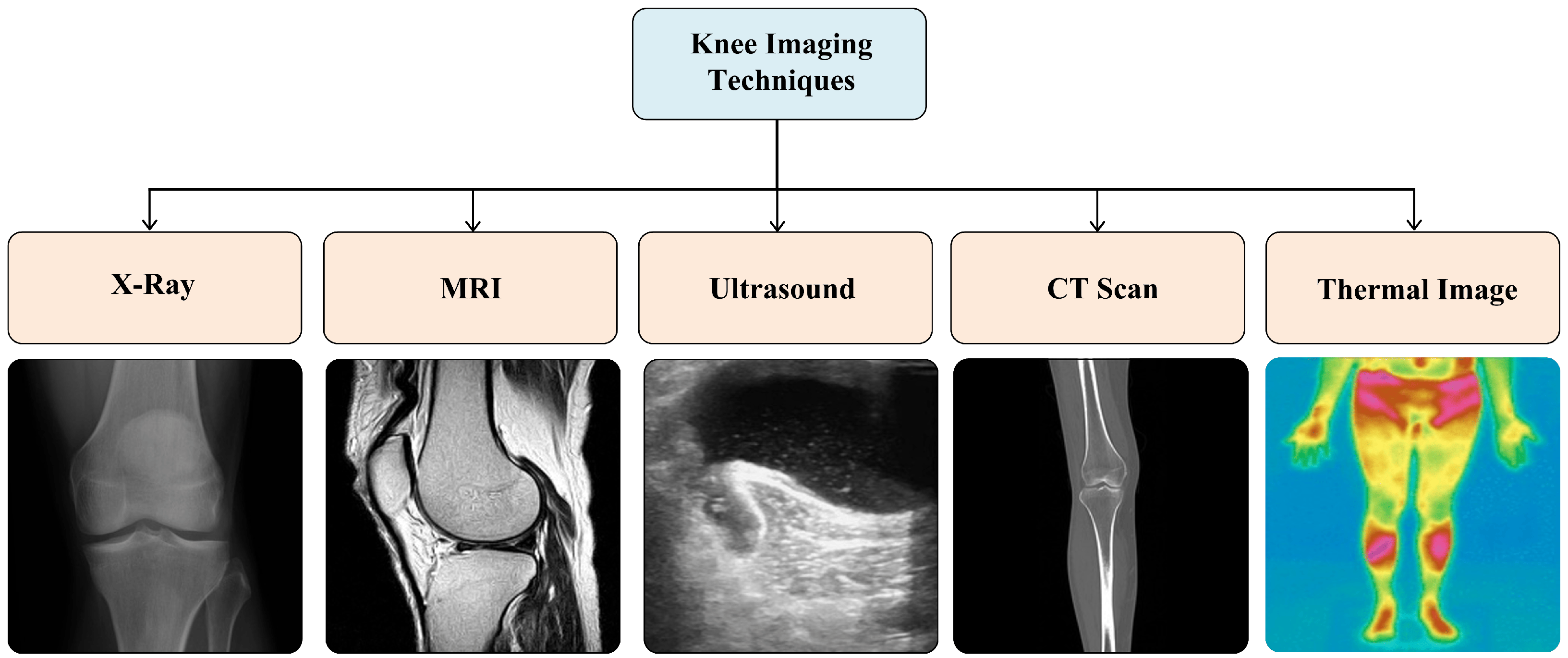

5.1. Imaging Modalities

5.2. X-Ray and MRI Dataset Sources

5.2.1. OAI and MOST Datasets

5.2.2. Other Datasets

| Reference | Year | Dataset Detail | No. of X-Ray Images | Image Dimension (Pixels) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OAI Dataset along with its variants and MOST Dataset | ||||

| Sohail et al. [112] | 2025 | OAI-modified by Chen [84] | 8260 | 299 × 299 |

| Ahmed et al. [85] | 2024 | OAI-obtained from Mendeley | 8260 | – |

| Malik et al. [86] | 2024 | OAI-obtained from Mendeley | 5778 | 299 × 299 |

| Touahema et al. [87] | 2024 | OAI (labeled by Boston University)—obtained from Mendeley | 4446 | 224 × 224 |

| Patil et al. [88] | 2024 | OAI | 2250 | 384 × 384 |

| Mohammed et al. [89] | 2023 | OAI obtained from Kaggle | 9786 | 224 × 224 |

| El-Ghany et al. [90] | 2023 | OAI assessed by Boston University X-ray reading center (BU) | 4446 | 224 × 224 |

| Guida et al. [98] | 2023 | OAI [Subset-1: both MRI and X-ray, Subset-2: Only X-ray] | Subset1: 1100 Subset2: 8821 | MRI (160 × 160), X-ray (600 × 220) |

| Pi et al. [91] | 2023 | OAI-modified by Chen [84] | 8260 | 224 × 224 (Model tested with different image sizes) |

| Pongsakonpruttikul et al. [5] | 2022 | OAI-modified by Chen [84] | 1650 | 224 × 224 |

| Wang et al. [92] | 2021 | OAI | 4506 | 224 × 224 |

| Yunus et al. [93] | 2022 | MOST | 3795 | 224 × 224 |

| Swiecick et al. [94] | 2021 | MOST | 18,503 | 700 × 700 |

| Norman et al. [95] | 2019 | OAI | 39,593 | 500 × 500 |

| Tiulpin et al. [96] | 2018 | MOST: for training, OAI: for validation and testing | 18,376 | 224 × 224 |

| Antony et al. [97] | 2017 | OAI & MOST | OAI: 4446 MOST: 2920 | 256 × 256 |

| Other datasets and dataset from local hospitals | ||||

| Touahema et al. [87] | 2024 | Medical Expert Public Dataset—collected from various hospitals and diagnostic centers in India | 1650 | 362 × 162 |

| Touahema et al. [87] | 2024 | El Kelaa des Sraghna Provincial Hospital | 30 | – |

| Alshamrani et al. [104] | 2023 | Dataset obtained from Kaggle | 3836 | 224 × 224 |

| Hengaju et al. [105] | 2022 | Bhaktapur Hospital | 350 | 256 × 256 |

| Abdullah et al. [106] | 2022 | Radiological center (KGS scan center, Madurai) | 3172 | 3000 × 1500 |

| Sikkandar et al. [107] | 2022 | Durma and Tumair General Hospital, Riyadh | 350 | 256 × 256 |

| Olsson et al. [108] | 2021 | Danderyd University Hospital | 6403 | 256 × 256 |

| Shamir et al. [109] | 2009 | Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (BLSA) | 350 | 1000 × 945 |

| Reference | Year | Dataset Detail | No. of Knee MRI | Image Dimension (Pixels) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guo et al. [113] | 2024 | OAI + FastMRI + SKI10 + private | 700 | – |

| Guida et al. [98] | 2023 | OAI [Subset-1: both MRI and X-ray, Subset-2: Only X-ray] | 1100 (number of knees) | After crop: 160 × 160 |

| Harman et al. [114] | 2023 | FastMRI+ | 663 | – |

| Hung et al. [115] | 2023 | private (584) + MRNet (120) | 704 | 512 × 512 |

| Schiratti et al. [99] | 2021 | OAI[ 2D MRI images of type “COR IW TSE” | 9280 | – |

| Karim et al. [100] | 2021 | MOST [2406 patients with MRI data] | 4678 MRI slices | Re-scaled to 360 × 360 |

| Guida et al. [81] | 2021 | OAI [3D DESS MRI—a sequence of 160 2D images] | 1100 | 384 × 384 |

| Du et al. [116] | 2018 | OAI | 4800 | 448 × 448 |

| Kumar et al. [110] | 2016 | SRM Medical College Hospital and Research Center | 15 | 256 × 256 |

| Marques et al. [111] | 2013 | Community based, Non-treatment Study | 268 | 170 × 170 |

5.3. Dataset Provenance, Label Reliability, and Data Hygiene

6. Data Preparation and Model Development

6.1. Data Augmentation

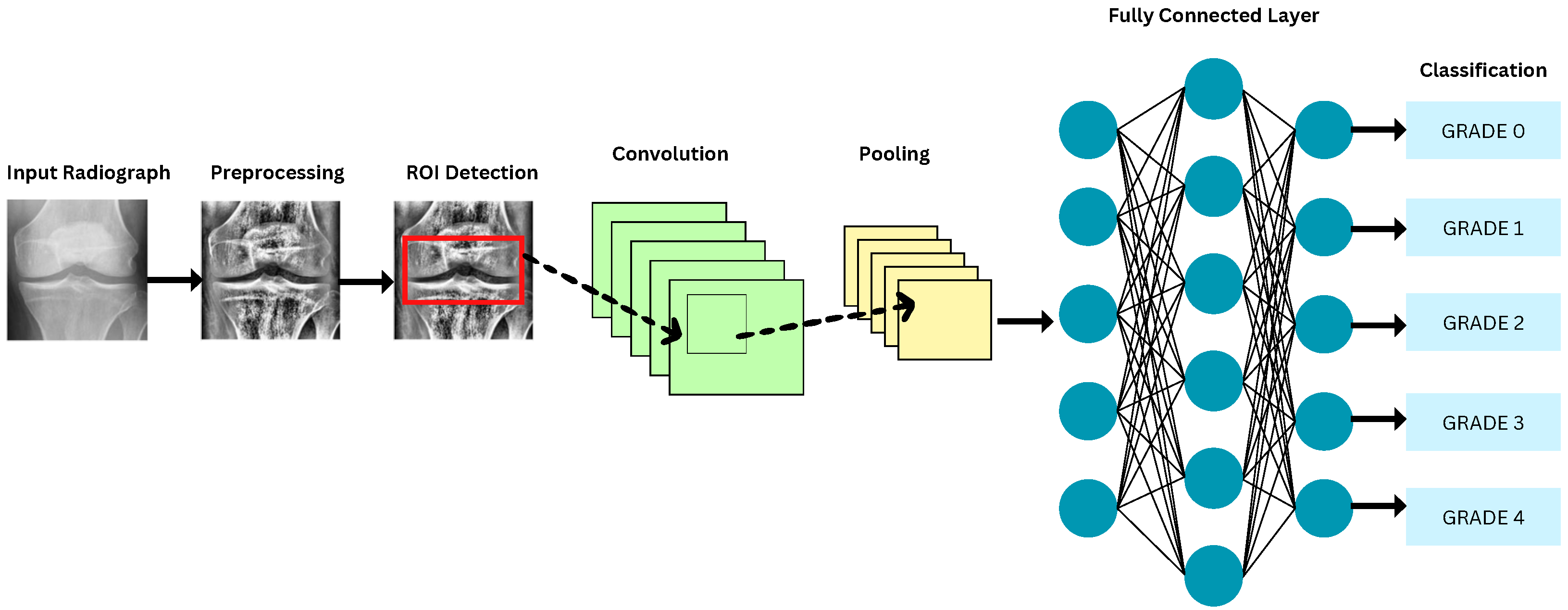

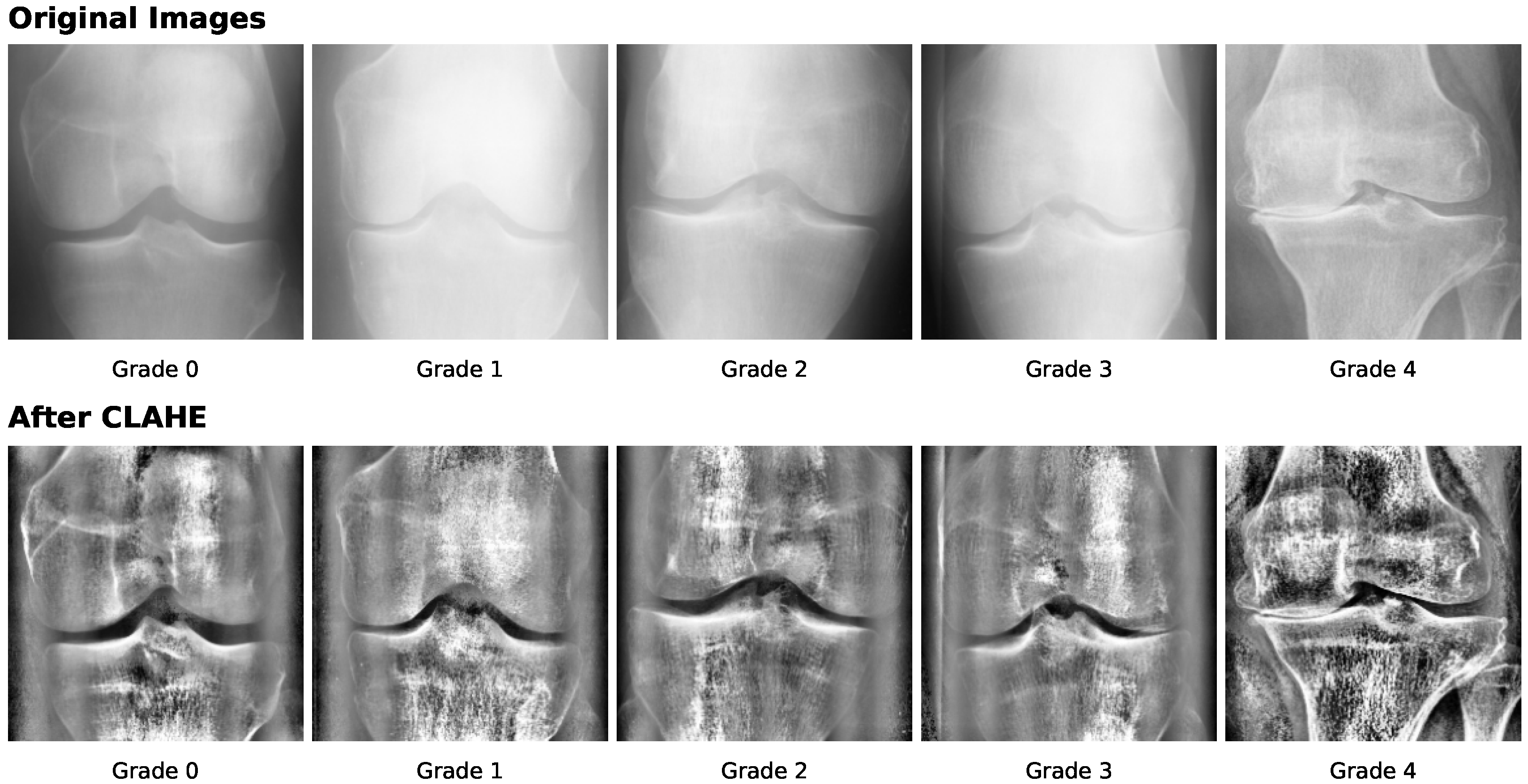

6.2. Preprocessing Methods

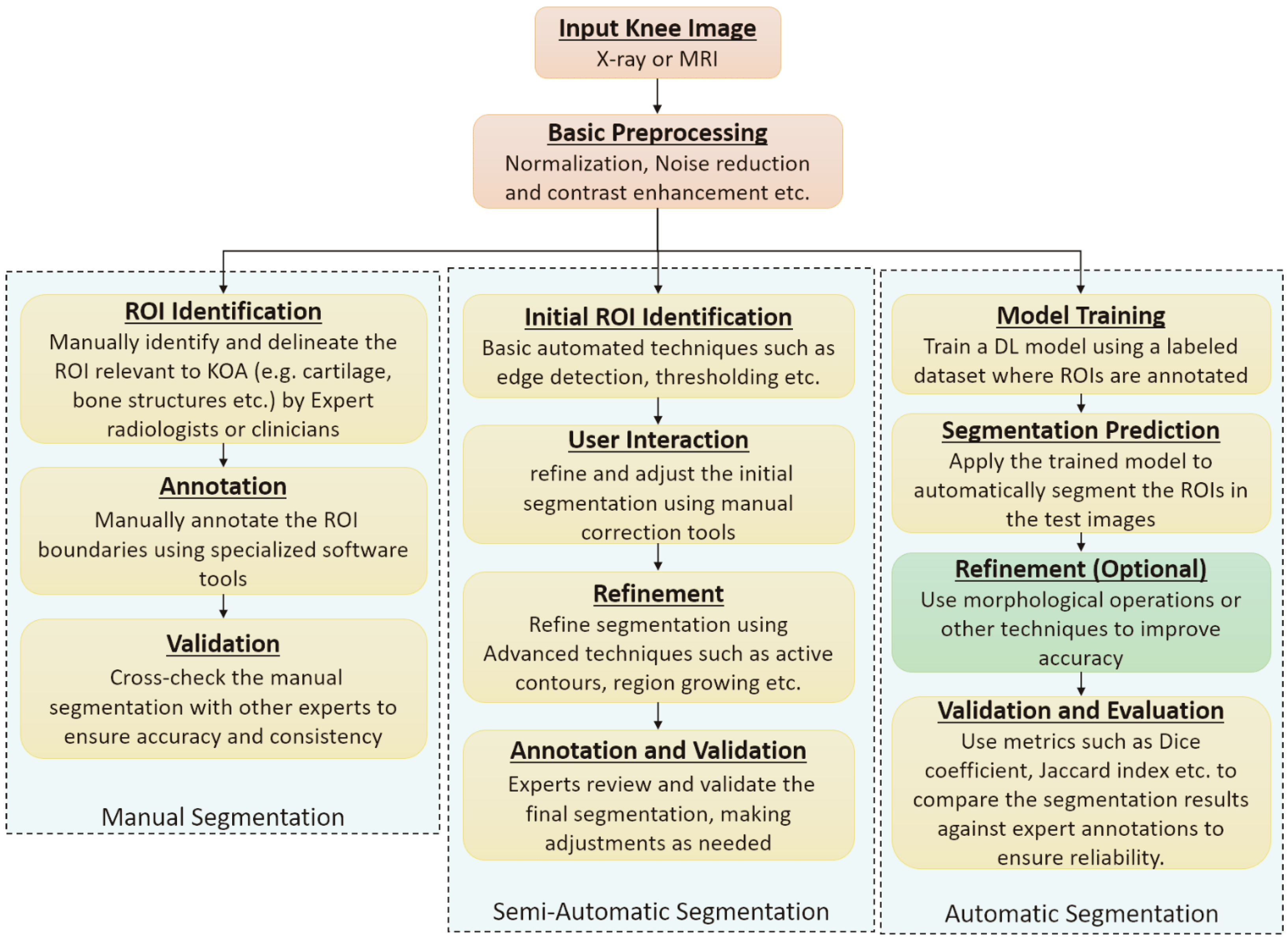

6.3. Segmentation Approaches

6.4. DL Models for KOA Classification

| Category | Architecture | References |

|---|---|---|

| Deep Learning | Residual Networks (ResNets) | [89,91,92,104,105,106,108,117,124,146,147,148,149,150,151,152,153] |

| DenseNets | [80,89,90,91,95,100,119,123,127,152,154] | |

| Visual Geometry Group (VGG) | [89,94,100,104,105,152,155,156,157] | |

| You Only Look Once (YOLO) | [5,92,93,158] | |

| EfficientNet | [91,159,160] | |

| Region based CNN (R-CNN) | [94,106,127] | |

| MobileNet | [89,153,161,162] | |

| AlexNet | [106,163] | |

| Darknet | [164] | |

| Inception | [89,112,153] | |

| ShuffleNet | [91] | |

| NASNet | [165] | |

| HRNet | [166] | |

| LENET | [167] | |

| Deep Siamese Network | [124] | |

| UNet | [95] | |

| CaffeNet | [157] | |

| Machine Learning | Support Vector Machines | [27,110,116,119,122,150,164,168,169,170] |

| k-Nearest Neighbours | [93,109,169,171,172] | |

| Random Forest Classifier | [169,173,174] | |

| Naive Bayes Classifier | [174] | |

| Hybrid Models | CNN with SVM, RF, and Gradient Boosting | [30] |

| Reference | Year | Dataset | Test Set Size | ROI Method | Imbalance Handling | Validation | Key Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sohail et al. [112] | 2025 | OAI | 826 | NR | Data Augmentation | internal | Acc: 92.25, F1: 92.30, K: 90.69 |

| Ahmed et al. [85] | 2024 | OAI | 1656 | NR | NR | internal | Acc: 56.28, F1: 63 |

| Touahema et al. [87] | 2024 | OAI | 1000 | NR | Data Augmentation | Internal | Acc: 97.20, F1: 97 |

| Malik et al. [86] | 2024 | OAI | 488 | NR | Data Augmentation | internal | Acc: 89.89, F1: 78.25 |

| Patil et al. [88] | 2024 | OAI | 125 | DFCN | NR | internal | Acc: 94 |

| Mohammed et al. [89] | 2023 | OAI | 1656 | NR | None | internal | Acc: 67, F1: 67 |

| El-Ghany et al. [90] | 2023 | OAI | 1778 | GradCAM | NR | internal | Acc: 95.93, F1: 87.08 |

| Guida et al. [98] | 2023 | OAI | 1755 | NR | undersampling | internal | Acc: 76 |

| Alshamran et al. [104] | 2023 | Kaggle | 845 | NR | stratified sampling | internal | Acc: 92.17, F1: 92 |

| Tariq et al. [152] | 2023 | OAI | 1656 | NR | None | internal | Acc: 98, F1: 97, K: 99 |

| Haseeb et al. [119] | 2023 | Kaggle | 2348 | NR | NR | internal | Acc: 90.1, F1: 88 |

| Aladhadh et al. [154] | 2023 | Mendeley VI, OAI | 2500 | CenterNet | NR | external | Acc: 99.14, F1: 99.44, Dice Score: 99.24 ± 0.03 |

| Kiruthika et al. [125] | 2022 | OAI, MOST | 3500 | FCN | NR | internal | Acc: 98.75, F1: 99.3 |

| Pongsakonpruttikul et al. [5] | 2022 | OAI | 150 | Manual | undersampling | internal | Acc: 86.7, F1: 61.1 |

| Abdullah et al. [106] | 2022 | private | 634 | RPN (Region Proposal Network) | NR | internal | Acc: 98.90, Dice Score: 98.90 |

| Yunus et al. [93] | 2022 | Mendeley | 1656 | YOLOv2-ONNX | NR | internal | Acc: 90.6, F1: 88.0 |

| Cueva et al. [124] | 2022 | OAI, private | 225 | NR | oversampling | external | Acc: 61.71 |

| Sikkandar et al. [107] | 2022 | Private | 70 | Local Center of Mass (LCM) | NR | internal | Acc: 72.01, K: 86 |

| Hengaju et al. [105] | 2022 | Private | 140 | Active Contour | NR | internal | Acc: 59 |

| Kondal et al. [127] | 2022 | OAI, private | 1175 | Mask RCNN | NR | external | F1: 73 |

| Swiecicki et al. [94] | 2021 | MOST | 3359 | RPN | NR | internal | Acc: 71.90, K: 75.9 |

| Wang et al. [92] | 2021 | OAI | 1660 | YOLO | NR | internal | Acc: 69.18 |

| Tiulpin et al. [117] | 2020 | OAI, MOST | 11,743 | Random Forest Regression Voting | NR | external | Acc: 67, K: 82 |

| Norman et al. [95] | 2019 | OAI | 5941 | U-Net | NR | internal | Acc: 78.36 |

| Pedoia et al. [123] | 2019 | OAI | 657 | Voxel Based Relaxometry | NR | internal | R: 76.99, Ssy: 77.94 |

| Du at al. [116] | 2018 | OAI | 100 | NR | NR | 10-fold CV | Acc: 70 |

| Kumar et al. [110] | 2016 | Private | 15 | Pixel-based segmentation | NR | internal | Acc: 86.67 |

| Reference | Year | Dataset | Test Set Size | ROI Method | Imbalance Handling | Validation | Key Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mohammed et al. [89] | 2023 | OAI | 1656 | NR | None | internal | Acc: 83, F1: 83 |

| El-Ghany et al. [90] | 2023 | OAI | 1778 | GradCAM | NR | internal | Acc: 93.78, F1: 89.27 |

| Pongsakonpruttikul et al. [5] | 2022 | OAI | 100 | Manual | undersampling | internal | Acc: 85, F1: 85 |

7. Discussion and Future Research Directions

- Lack of availability of a balanced dataset to train the models makes them perform poorly for new and unseen data of the minority class.

- In an unbalanced dataset, traditional evaluation metrics such as accuracy become misleading as high accuracy can be achieved by simply predicting the majority class all the time, while still performing poorly on the minority class.

- The quality of the input images for model training requires multiple levels of preprocessing techniques to make them suitable for model training.

- In most of the available datasets, many images get discarded due to poor resolution or absence of ROI, which further depicts the problem of class imbalance.

- Requirement of a huge amount of computing resources to train such a large number of images.

- The labeling of the data points is done by radiologists, which introduces subjectivity in the overall process. The same knee X-ray image can be identified as belonging to separate KL grades by different radiologists. This makes the dataset available for training ambiguous and generates further inconsistency in predicting the actual severity of KOA.

- Potential data leakage can occur when images from the same patient, such as left and right knees or longitudinal scans, appear in both training and testing sets, leading to inflated performance estimates and reduced model generalizability.

- Handling Class Imbalance and Performance Evaluation: Class imbalance can reduce the performance of DL models if not properly addressed. Techniques such as over-sampling, under-sampling, and synthetic data generation can help balance the classes, and creating new datasets with more representative samples or combining data from multiple repositories can further improve model accuracy [175]. In addition, accuracy alone may be misleading for imbalanced datasets, so metrics like sensitivity, specificity, and F1-score should be used to evaluate and compare the performance of models, specifically for healthcare applications [176].

- Enhancements in DL models: Some of the studies [177] suggested that model computations can be optimized by changing the shape of the convolutional kernel and using texture memory. Other approaches can be explored to reduce the model computations. Collecting large amounts of malignant data for model training, using effective preprocessing techniques for the best feature extraction, and gathering information analysis about the knee can also further improve model performance.

- Model Complexity: The selection of more complex and accurate models that can deduce a better correlation between the pixel values in the preprocessed X-ray images and KOA severity according to the KL grading scale can improve the overall performance of DL-based models. With rapid improvements in the field of AI and ML and their applications, better and more accurate architectures are being proposed every year [178]. Therefore, newer architectures can be used to identify features in knee X-rays and classify them according to KOA severity.

- Other efficient DL architectures: The usage of Recurrent Neural Networks, Transformers, Reinforcement Learning, and Generative Adversarial Networks can also be explored for KOA detection and classification.

- Multimodal Large Models: Multimodal large models that combine knee images with clinical, demographic, or textual data can capture complex relationships between different data types. These models have shown strong performance in medical image analysis [179,180] and can help improve KOA classification accuracy and provide better interpretability.

- Data Hygiene and Label Reliability: Deep learning models for KOA classification strongly depend on the quality of training data and label consistency. Commonly used public datasets such as OAI and MOST rely on expert-assigned KL grades, which are subjective and show variability across readers, especially for borderline grades. This introduces unavoidable label noise. In addition, these datasets are bilateral and longitudinal, meaning that images from the same patient (left and right knees or follow-up visits) may appear multiple times. If data splitting is done at the image level instead of the patient level, data leakage can occur and lead to overestimated model performance. Therefore, future studies should apply patient-wise data splitting and clearly report dataset handling procedures. At present, KOA models are better suited for clinical support tasks such as triage and quality assurance rather than independent diagnosis.

- Regulatory and Clinical Validation: In addition to technical accuracy, KOA models require thorough clinical validation before deployment. This includes evaluation using standardized protocols, external testing on independent datasets, and clear reporting of dataset sources and validation strategies. Adherence to regulatory guidelines is necessary to ensure model safety, reliability, and clinical usefulness.

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arden, N.; Nevitt, M.C. Osteoarthritis: Epidemiology. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2006, 20, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, U.S.D.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Niu, J.; Zhang, B.; Felson, D.T. Increasing prevalence of knee pain and symptomatic knee osteoarthritis: Survey and cohort data. Ann. Intern. Med. 2011, 155, 725–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Kim, S.J. Prevalence of knee osteoarthritis, risk factors, and quality of life: The Fifth Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 2017, 20, 809–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saini, D.; Chand, T.; Chouhan, D.K.; Prakash, M. A comparative analysis of automatic classification and grading methods for knee osteoarthritis focussing on X-Ray images. Biocybern. Biomed. Eng. 2021, 41, 419–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongsakonpruttikul, N.; Angthong, C.; Kittichai, V.; Chuwongin, S.; Puengpipattrakul, P.; Thongpat, P.; Boonsang, S.; Tongloy, T. Artificial intelligence assistance in radiographic detection and classification of knee osteoarthritis and its severity: A cross-sectional diagnostic study. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2022, 26, 1549–1558. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Ji, Q.; Ni, M.; Zhang, G.; Wang, Y. Automatic assessment of knee osteoarthritis severity in portable devices based on deep learning. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2022, 17, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkotis, C.; Moustakidis, S.; Papageorgiou, E.; Giakas, G.; Tsaopoulos, D. Machine learning in knee osteoarthritis: A review. Osteoarthr. Cartil. Open 2020, 2, 100069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeoh, P.S.Q.; Lai, K.W.; Goh, S.L.; Hasikin, K.; Hum, Y.C.; Tee, Y.K.; Dhanalakshmi, S. Emergence of Deep Learning in Knee Osteoarthritis Diagnosis. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2021, 2021, 4931437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yick, H.T.V.; Chan, P.K.; Wen, C.; Fung, W.C.; Yan, C.H.; Chiu, K.Y. Artificial intelligence reshapes current understanding and management of osteoarthritis: A narrative review. J. Orthop. Trauma Rehabil. 2022, 29, 22104917221082315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.S.; Chan, P.K.; Wen, C.; Fung, W.C.; Cheung, A.; Chan, V.W.K.; Cheung, M.H.; Fu, H.; Yan, C.H.; Chiu, K.Y. Artificial intelligence in diagnosis of knee osteoarthritis and prediction of arthroplasty outcomes: A review. Arthroplasty 2022, 4, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramazanian, T.; Fu, S.; Sohn, S.; Taunton, M.J.; Kremers, H.M. Prediction models for knee osteoarthritis: Review of current models and future directions. Arch. Bone Jt. Surg. 2023, 11, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Cigdem, O.; Deniz, C.M. Artificial Intelligence in Knee Osteoarthritis: A Comprehensive Review. Osteoarthr. Imaging 2023, 3, 100161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Ou, L.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Liu, K.; Kuang, J. The value of deep learning-based X-ray techniques in detecting and classifying K-L grades of knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Radiol. 2025, 35, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Touahema, S.; Zaimi, I.; Zrira, N.; Ngote, M.N. How Can Artificial Intelligence Identify Knee Osteoarthritis from Radiographic Images with Satisfactory Accuracy?: A Literature Review for 2018–2024. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teoh, Y.X.; Othmani, A.; Goh, S.L.; Usman, J.; Lai, K.W. Deciphering knee osteoarthritis diagnostic features with explainable artificial intelligence: A systematic review. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 109080–109108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, T.; Suhail, Z.; Nawaz, Z. A Review for automated classification of knee osteoarthritis using KL grading scheme for X-rays. Biomed. Eng. Lett. 2025, 15, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, S.; Wang, H. The Potential Roles of Ferroptosis in Pathophysiology and Treatment of Musculoskeletal Diseases-Opportunities, Challenges, and Perspectives. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madry, H.; Luyten, F.P.; Facchini, A. Biological aspects of early osteoarthritis. Knee Surg. Sport. Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2012, 20, 407–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieland, H.A.; Michaelis, M.; Kirschbaum, B.J.; Rudolphi, K.A. Osteoarthritis—An untreatable disease? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2005, 4, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, T.W.; Felson, D.T. Mechanisms of osteoarthritis (OA) pain. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 2018, 16, 611–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martel-Pelletier, J.; Barr, A.J.; Cicuttini, F.M.; Conaghan, P.G.; Cooper, C.; Goldring, M.B.; Goldring, S.R.; Jones, G.; Teichtahl, A.J.; Pelletier, J.P. Osteoarthritis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2016, 2, 16072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heidari, B. Knee osteoarthritis prevalence, risk factors, pathogenesis and features: Part I. Casp. J. Intern. Med. 2011, 2, 205–212. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, L. Osteoarthritis of the knee. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheth, N.P.; Foran, J.R.H. Arthritis of the Knee—OrthoInfo—AAOS—orthoinfo.aaos.org. 2024. Available online: https://orthoinfo.aaos.org/en/diseases--conditions/arthritis-of-the-knee/ (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Kim, Y.M.; Joo, Y.B. Patellofemoral osteoarthritis. Knee Surg. Relat. Res. 2012, 24, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roemer, F.W.; Zhang, Y.; Niu, J.; Lynch, J.A.; Crema, M.D.; Marra, M.D.; Nevitt, M.C.; Felson, D.T.; Hughes, L.B.; El-Khoury, G.Y.; et al. Tibiofemoral joint osteoarthritis: Risk factors for MR-depicted fast cartilage loss over a 30-month period in the multicenter osteoarthritis study. Radiology 2009, 252, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gornale, S.S.; Patravali, P.U.; Marathe, K.S.; Hiremath, P.S. Determination of osteoarthritis using histogram of oriented gradients and multiclass SVM. Int. J. Image Graph. Signal Process. 2017, 9, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, A.; Li, H.; Wang, D.; Zhong, J.; Chen, Y.; Lu, H. Global, regional prevalence, incidence and risk factors of knee osteoarthritis in population-based studies. EClinicalMedicine 2020, 29, 100587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, J.C.; Przkora, R.; Cruz-Almeida, Y. Knee osteoarthritis: Pathophysiology and current treatment modalities. J. Pain Res. 2018, 11, 2189–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bany Muhammad, M.; Yeasin, M. Interpretable and parameter optimized ensemble model for knee osteoarthritis assessment using radiographs. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 14348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohn, M.D.; Sassoon, A.A.; Fernando, N.D. Classifications in brief: Kellgren-Lawrence classification of osteoarthritis. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2016, 474, 1886–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterfy, C.; Guermazi, A.; Zaim, S.; Tirman, P.; Miaux, Y.; White, D.; Kothari, M.; Lu, Y.; Fye, K.; Zhao, S.; et al. Whole-organ magnetic resonance imaging score (WORMS) of the knee in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2004, 12, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, D.J.; Lo, G.H.; Gale, D.; Grainger, A.J.; Guermazi, A.; Conaghan, P.G. The reliability of a new scoring system for knee osteoarthritis MRI and the validity of bone marrow lesion assessment: BLOKS (Boston–Leeds Osteoarthritis Knee Score). Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2008, 67, 206–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, D.J.; Guermazi, A.; Lo, G.H.; Grainger, A.J.; Conaghan, P.G.; Boudreau, R.M.; Roemer, F.W. Evolution of semi-quantitative whole joint assessment of knee OA: MOAKS (MRI Osteoarthritis Knee Score). Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2011, 19, 990–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stern, C.; Jordan, Z.; McArthur, A. Developing the review question and inclusion criteria. Am. J. Nurs. 2014, 114, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very Deep Convolutional Networks for Large-Scale Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR 2015), San Diego, CA, USA, 7–9 May 2015; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 26–30 June 2016; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, G.; Liu, Z.; Van Der Maaten, L.; Weinberger, K.Q. Densely connected convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 4700–4708. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, A.G.; Zhu, M.; Chen, B.; Kalenichenko, D.; Wang, W.; Weyand, T.; Andreetto, M.; Adam, H. Mobilenets: Efficient convolutional neural networks for mobile vision applications. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1704.04861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Le, Q. Efficientnet: Rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning, Long Beach, CA, USA, 10–15 June 2019; PMLR: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 6105–6114. [Google Scholar]

- Sarker, I.H. Deep learning: A comprehensive overview on techniques, taxonomy, applications and research directions. SN Comput. Sci. 2021, 2, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Yun, J.; Cho, Y.; Shin, K.; Jang, R.; Bae, H.j.; Kim, N. Deep learning in medical imaging. Neurospine 2019, 16, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Gao, K.; Liu, B.; Pan, C.; Liang, K.; Yan, L.; Ma, J.; He, F.; Zhang, S.; Pan, S.; et al. Advances in deep learning-based medical image analysis. Health Data Sci. 2021, 2021, 8786793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puttagunta, M.; Ravi, S. Medical image analysis based on deep learning approach. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2021, 80, 24365–24398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, R.; Nishio, M.; Do, R.K.G.; Togashi, K. Convolutional neural networks: An overview and application in radiology. Insights Imaging 2018, 9, 611–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indolia, S.; Goswami, A.K.; Mishra, S.P.; Asopa, P. Conceptual understanding of convolutional neural network—A deep learning approach. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2018, 132, 679–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzubaidi, L.; Zhang, J.; Humaidi, A.J.; Al-Dujaili, A.; Duan, Y.; Al-Shamma, O.; Santamaría, J.; Fadhel, M.A.; Al-Amidie, M.; Farhan, L. Review of deep learning: Concepts, CNN architectures, challenges, applications, future directions. J. Big Data 2021, 8, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeCun, Y.; Bottou, L.; Bengio, Y.; Haffner, P. Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. Proc. IEEE 1998, 86, 2278–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Yu, W. Improved Convolutional Neural Image Recognition Algorithm based on LeNet-5. J. Comput. Netw. Commun. 2022, 2022, 1636203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Commun. ACM Mag. 2012, 60, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thalagala, S.; Walgampaya, C. Application of AlexNet convolutional neural network architecture-based transfer learning for automated recognition of casting surface defects. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Research Conference on Smart Computing and Systems Engineering (SCSE), Colombo, Sri Lanka, 16 September 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; Volume 4, pp. 129–136. [Google Scholar]

- Zeiler, M.D.; Fergus, R. Visualizing and Understanding Convolutional Networks. In Proceedings of the 13th European Conference on Computer Vision, ECCV 2014, Zurich, Switzerland, 6–12 September 2014; Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; Volume 8689, pp. 818–833. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, L.; Feng, Y.; Majeed, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.; Karkee, M.; Zhang, Q. Kiwifruit detection in field images using Faster R-CNN with ZFNet. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2018, 51, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Wang, J.; Cao, S.; Li, B. Application of a Novel and Improved VGG-19 Network in the Detection of Workers Wearing Masks. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1518, 012041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szegedy, C.; Liu, W.; Jia, Y.; Sermanet, P.; Reed, S.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Vanhoucke, V.; Rabinovich, A. Going deeper with convolutions. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Szegedy, C.; Vanhoucke, V.; Ioffe, S.; Shlens, J.; Wojna, Z. Rethinking the inception architecture for computer vision. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 26–30 June 2016; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 2818–2826. [Google Scholar]

- Girshick, R.; Donahue, J.; Darrell, T.; Malik, J. Rich feature hierarchies for accurate object detection and semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Columbus, OH, USA, 23–28 June 2014; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 580–587. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards Real-Time Object Detection with Region Proposal Networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2017, 39, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Fu, Y.L.; Zhu, D. ResNet and Its Application to Medical Image Processing: Research Progress and Challenges. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2023, 240, 107660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diwan, T.; Anirudh, G.; Tembhurne, J.V. Object detection using YOLO: Challenges, architectural successors, datasets and applications. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2023, 82, 9243–9275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Li, Y.; Zou, T.; Wang, X.; You, J.; Luo, Y. A Novel Image Classification Approach via Dense-MobileNet Models. Mob. Inf. Syst. 2020, 2020, 7602384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koonce, B. EfficientNet. In Convolutional Neural Networks with Swift for Tensorflow: Image Recognition and Dataset Categorization; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 109–123. [Google Scholar]

- Zoph, B.; Vasudevan, V.; Shlens, J.; Le, Q.V. Learning Transferable Architectures for Scalable Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 8697–8710. [Google Scholar]

- Cano, E.; Mendoza-Avilés, J.; Areiza, M.; Guerra, N.; Mendoza-Valdés, J.L.; Rovetto, C.A. Multi skin lesions classification using fine-tuning and data-augmentation applying NASNet. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2021, 7, e371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Mao, H.; Wu, C.Y.; Feichtenhofer, C.; Darrell, T.; Xie, S. A convnet for the 2020s. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 11976–11986. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, S.; Debnath, S.; Hu, R.; Chen, X.; Liu, Z.; Kweon, I.S.; Xie, S. ConvNeXt V2: Co-designing and Scaling ConvNets with Masked Autoencoders. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 16133–16142. [Google Scholar]

- Tammina, S. Transfer learning using VGG-16 with deep convolutional neural network for classifying images. Int. J. Sci. Res. Publ. 2019, 9, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szegedy, C.; Ioffe, S.; Vanhoucke, V.; Alemi, A. Inception-v4, inception-resnet and the impact of residual connections on learning. In Proceedings of the 31st AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, San Francisco, CA, USA, 4–9 February 2017; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 31. [Google Scholar]

- Si, C.; Yu, W.; Zhou, P.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, X.; Yan, S. Inception transformer. In Proceedings of the NIPS’22: 36th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, New Orleans, LA, USA, 28 November–9 December 2022; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 23495–23509. [Google Scholar]

- Iandola, F.; Moskewicz, M.; Karayev, S.; Girshick, R.; Darrell, T.; Keutzer, K. Densenet: Implementing efficient convnet descriptor pyramids. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1404.1869. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, P.; Ergu, D.; Liu, F.; Cai, Y.; Ma, B. A Review of Yolo algorithm developments. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2022, 199, 1066–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, X.; Chen, X.; Xu, X.; Xie, L.; Chen, X.; Hong, Z.; Bai, H.; Liu, X.; Chen, Q.; Li, L.; et al. Recent development in X-ray imaging technology: Future and challenges. Research 2021, 2021, 9892152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajla, V.; Gupta, A.; Khatak, A. Analysis of x-ray images with image processing techniques: A review. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Computing Communication and Automation (ICCCA), Greater Noida, India, 14–15 December 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Nouh, M.R.; Eid, A.F. Magnetic resonance imaging of the spinal marrow: Basic understanding of the normal marrow pattern and its variant. World J. Radiol. 2015, 7, 448–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, R.; Venkatesan, R.; Geethanath, S. Role of MRI in medical diagnostics. Resonance 2015, 20, 1003–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, L.; Finlay, K.; Jurriaans, E. Ultrasound of the knee. Skelet. Radiol. 2001, 30, 361–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victor, J.; Van Doninck, D.; Labey, L.; Innocenti, B.; Parizel, P.; Bellemans, J. How precise can bony landmarks be determined on a CT scan of the knee? Knee 2009, 16, 358–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Ma, B.; Hu, M.; Zhai, G.; Sun, W.Q.; Yang, S.X. Objective Bi-Modal Assessment of Knee Osteoarthritis Severity Grades: Model and Mechanism. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 4508611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasser, Y.; El Hassouni, M.; Hans, D.; Jennane, R. A discriminative shape-texture convolutional neural network for early diagnosis of knee osteoarthritis from X-ray images. Phys. Eng. Sci. Med. 2023, 46, 827–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guida, C.; Zhang, M.; Shan, J. Knee osteoarthritis classification using 3D CNN and MRI. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterfy, C.G.; Schneider, E.; Nevitt, M. The osteoarthritis initiative: Report on the design rationale for the magnetic resonance imaging protocol for the knee. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2008, 16, 1433–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, N.A.; Nevitt, M.C.; Gross, K.D.; Hietpas, J.; Glass, N.A.; Lewis, C.E.; Torner, J.C. The Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study (MOST): Opportunities for rehabilitation research. PM R J. Inj. Funct. Rehabil. 2013, 5, 647–654. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, P. Knee Osteoarthritis Severity Grading Dataset. Mendeley Data, V1. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, R.; Imran, A.S. Knee Osteoarthritis Analysis Using Deep Learning and XAI on X-rays. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 68870–68879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, I.; Yasmin, M.; Iqbal, A.; Raza, M.; Chun, C.J.; Al-antari, M.A. A novel framework integrating ensemble transfer learning and Ant Colony Optimization for Knee Osteoarthritis severity classification. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2024, 83, 86923–86954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touahema, S.; Zaimi, I.; Zrira, N.; Ngote, M.N.; Doulhousne, H.; Aouial, M. MedKnee: A New Deep Learning-Based Software for Automated Prediction of Radiographic Knee Osteoarthritis. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, A.R.; Salunkhe, S.S. Classification and risk estimation of osteoarthritis using deep learning methods. Meas. Sens. 2024, 35, 101279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.S.; Hasanaath, A.A.; Latif, G.; Bashar, A. Knee Osteoarthritis Detection and Severity Classification Using Residual Neural Networks on Preprocessed X-ray Images. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Ghany, S.; Elmogy, M.; Abd El-Aziz, A. A fully automatic fine tuned deep learning model for knee osteoarthritis detection and progression analysis. Egypt. Inform. J. 2023, 24, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pi, S.W.; Lee, B.D.; Lee, M.S.; Lee, H.J. Ensemble deep-learning networks for automated osteoarthritis grading in knee X-ray images. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 22887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Gao, T.; Du, L.; Liu, W. An Automatic Knee Osteoarthritis Diagnosis Method Based on Deep Learning: Data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. J. Healthc. Eng. 2021, 2021, 5586529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yunus, U.; Amin, J.; Sharif, M.; Yasmin, M.; Kadry, S.; Krishnamoorthy, S. Recognition of Knee Osteoarthritis (KOA) Using YOLOv2 and Classification Based on Convolutional Neural Network. Life 2022, 12, 1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swiecicki, A.; Li, N.; O’Donnell, J.; Said, N.; Yang, J.; Mather, R.C.; Jiranek, W.A.; Mazurowski, M.A. Deep learning-based algorithm for assessment of knee osteoarthritis severity in radiographs matches performance of radiologists. Comput. Biol. Med. 2021, 133, 104334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, B.; Pedoia, V.; Noworolski, A.; Link, T.M.; Majumdar, S. Applying densely connected convolutional neural networks for staging osteoarthritis severity from plain radiographs. J. Digit. Imaging 2019, 32, 471–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiulpin, A.; Thevenot, J.; Rahtu, E.; Lehenkari, P.; Saarakkala, S. Automatic knee osteoarthritis diagnosis from plain radiographs: A deep learning-based approach. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antony, J.; McGuinness, K.; Moran, K.; O’Connor, N.E. Automatic detection of knee joints and quantification of knee osteoarthritis severity using convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Machine Learning and Data Mining in Pattern Recognition, MLDM 2017, New York, NY, USA, 15–20 July 2017; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 376–390. [Google Scholar]

- Guida, C.; Zhang, M.; Shan, J. Improving knee osteoarthritis classification using multimodal intermediate fusion of X-ray, MRI, and clinical information. Neural Comput. Appl. 2023, 35, 9763–9772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiratti, J.B.; Dubois, R.; Herent, P.; Cahané, D.; Dachary, J.; Clozel, T.; Wainrib, G.; Keime-Guibert, F.; Lalande, A.; Pueyo, M.; et al. A deep learning method for predicting knee osteoarthritis radiographic progression from MRI. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2021, 23, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, M.R.; Jiao, J.; Doehmen, T.; Cochez, M.; Beyan, O.; Rebholz-Schuhmann, D.; Decker, S. DeepKneeExplainer: Explainable knee osteoarthritis diagnosis from radiographs and magnetic resonance imaging. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 39757–39780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bien, N.; Rajpurkar, P.; Ball, R.L.; Irvin, J.; Park, A.; Jones, E.; Bereket, M.; Patel, B.N.; Yeom, K.W.; Shpanskaya, K.; et al. Deep-learning-assisted diagnosis for knee magnetic resonance imaging: Development and retrospective validation of MRNet. PLoS Med. 2018, 15, e1002699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoll, F.; Zbontar, J.; Sriram, A.; Muckley, M.J.; Bruno, M.; Defazio, A.; Parente, M.; Geras, K.J.; Katsnelson, J.; Chandarana, H.; et al. fastMRI: A publicly available raw k-space and DICOM dataset of knee images for accelerated MR image reconstruction using machine learning. Radiol. Artif. Intell. 2020, 2, e190007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, R.; Yaman, B.; Zhang, Y.; Stewart, R.; Dixon, A.; Knoll, F.; Huang, Z.; Lui, Y.W.; Hansen, M.S.; Lungren, M.P. fastMRI+, clinical pathology annotations for knee and brain fully sampled magnetic resonance imaging data. Sci. Data 2022, 9, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshamrani, H.A.; Rashid, M.; Alshamrani, S.S.; Alshehri, A.H. Osteo-NeT: An Automated System for Predicting Knee Osteoarthritis from X-ray Images Using Transfer-Learning-Based Neural Networks Approach. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hengaju, U. Classification of Knee Osteoarthritis using CNN. Adv. Image Process. Pattern Recognit. 2022, 5, 25–38. [Google Scholar]

- Abdullah, S.S.; Rajasekaran, M.P. Automatic detection and classification of knee osteoarthritis using deep learning approach. La Radiol. Medica 2022, 127, 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikkandar, M.Y.; Begum, S.S.; Alkathiry, A.A.; Alotaibi, M.S.N.; Manzar, M.D. Automatic detection and classification of human knee osteoarthritis using convolutional neural networks. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2022, 70, 4279–4291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, S.; Akbarian, E.; Lind, A.; Razavian, A.S.; Gordon, M. Automating classification of osteoarthritis according to Kellgren-Lawrence in the knee using deep learning in an unfiltered adult population. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2021, 22, 844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamir, L.; Ling, S.M.; Scott, W.W.; Bos, A.; Orlov, N.; Macura, T.J.; Eckley, D.M.; Ferrucci, L.; Goldberg, I.G. Knee X-Ray Image Analysis Method for Automated Detection of Osteoarthritis. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2009, 56, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.A.; Jayanthy, A. Classification of MRI images in 2D coronal view and measurement of articular cartilage thickness for early detection of knee osteoarthritis. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Recent Trends in Electronics, Information & Communication Technology (RTEICT), Bangalore, India, 20–21 May 2016; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 1907–1911. [Google Scholar]

- Marques, J.; Genant, H.K.; Lillholm, M.; Dam, E.B. Diagnosis of osteoarthritis and prognosis of tibial cartilage loss by quantification of tibia trabecular bone from MRI. Magn. Reson. Med. 2013, 70, 568–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohail, M.; Azad, M.M.; Kim, H.S. Knee osteoarthritis severity detection using deep inception transfer learning. Comput. Biol. Med. 2025, 186, 109641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Yan, P.; Qin, Y.; Liu, M.; Ma, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, R.; Luo, H.; Lv, S. Automated measurement and grading of knee cartilage thickness: A deep learning-based approach. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1337993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harman, F.; Selver, M.A.; Baris, M.M.; Canturk, A.; Oksuz, I. Deep Learning-Based Meniscus Tear Detection From Accelerated MRI. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 144349–144363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, T.N.K.; Vy, V.P.T.; Tri, N.M.; Hoang, L.N.; Tuan, L.V.; Ho, Q.T.; Le, N.Q.K.; Kang, J.H. Automatic detection of meniscus tears using backbone convolutional neural networks on knee MRI. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2023, 57, 740–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Almajalid, R.; Shan, J.; Zhang, M. A novel method to predict knee osteoarthritis progression on MRI using machine learning methods. IEEE Trans. Nanobiosci. 2018, 17, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiulpin, A.; Saarakkala, S. Automatic Grading of Individual Knee Osteoarthritis Features in Plain Radiographs Using Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. Diagnostics 2020, 10, 932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidyasaraswathi, H.N.; Hanumantharaju, M.C. Review of Various Histogram Based Medical Image Enhancement Techniques. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Advanced Research in Computer Science Engineering & Technology (ICARCSET 2015), Unnao, India, 6–7 March 2015; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Haseeb, A.; Khan, M.A.; Shehzad, F.; Alhaisoni, M.; Khan, J.A.; Kim, T.; Cha, J.H. Knee Osteoarthritis Classification Using X-Ray Images Based on Optimal Deep Neural Network. Comput. Syst. Sci. Eng. 2023, 47, 2397–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizer, S.; Johnston, R.; Ericksen, J.; Yankaskas, B.; Muller, K. Contrast-limited adaptive histogram equalization: Speed and effectiveness. In Proceedings of the First Conference on Visualization in Biomedical Computing, Atlanta, GA, USA, 22–25 May 1990; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 1990; pp. 337–345. [Google Scholar]

- Reza, A.M. Realization of the contrast limited adaptive histogram equalization (CLAHE) for real-time image enhancement. J. Vlsi Signal Process. Syst. Signal Image Video Technol. 2004, 38, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubkaddi, S.; Ravikumar, K. Early detection of knee osteoarthritis using SVM classifier. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Adv. Technol. 2017, 5, 259–262. [Google Scholar]

- Pedoia, V.; Lee, J.; Norman, B.; Link, T.M.; Majumdar, S. Diagnosing osteoarthritis from T2 maps using deep learning: An analysis of the entire Osteoarthritis Initiative baseline cohort. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2019, 27, 1002–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cueva, J.H.; Castillo, D.; Espinós-Morató, H.; Durán, D.; Díaz, P.; Lakshminarayanan, V. Detection and classification of knee osteoarthritis. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiruthika, D.; Judith, J. Automatic Detection of Knee Joints and Quantification of Knee Osteoarthritis Severity using Modified Fully connected Convolutional Neural Networks. Int. J. Innov. Sci. Res. Technol. 2022, 7, 569–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Gao, L.; Shi, X.; Allen, K.; Yang, L. Fully automatic knee osteoarthritis severity grading using deep neural networks with a novel ordinal loss. Comput. Med. Imaging Graph. 2019, 75, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kondal, S.; Kulkarni, V.; Gaikwad, A.; Kharat, A.; Pant, A. Automatic grading of knee osteoarthritis on the Kellgren-Lawrence scale from radiographs using convolutional neural networks. In Advances in Deep Learning, Artificial Intelligence and Robotics, Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Deep Learning, Artificial Intelligence and Robotics (ICDLAIR), Baronissi, Italy, 7–18 December 2020; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 163–173. [Google Scholar]

- Bayramoglu, N.; Tiulpin, A.; Hirvasniemi, J.; Nieminen, M.T.; Saarakkala, S. Adaptive segmentation of knee radiographs for selecting the optimal ROI in texture analysis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2020, 28, 941–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anifah, L.; Purnama, I.K.E.; Hariadi, M.; Purnomo, M.H. Automatic segmentation of impaired joint space area for osteoarthritis knee on x-ray image using gabor filter based morphology process. IPTEK J. Technol. Sci. 2011, 22, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirvasniemi, J.; Thevenot, J.; Immonen, V.; Liikavainio, T.; Pulkkinen, P.; Jämsä, T.; Arokoski, J.; Saarakkala, S. Quantification of differences in bone texture from plain radiographs in knees with and without osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2014, 22, 1724–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, V.B.; Feng, S.; Wang, S.; White, S.; Ainslie, M.; Brett, A.; Holmes, A.; Charles, H.C. Trabecular morphometry by fractal signature analysis is a novel marker of osteoarthritis progression. Arthritis Rheum. Off. J. Am. Coll. Rheumatol. 2009, 60, 3711–3722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soh, S.S.; Swee, T.T.; Ying, S.S.; En, C.Z.; bin Mazenan, M.N.; Meng, L.K. Magnetic resonance image segmentation for knee osteoarthritis using active shape models. In Proceedings of the 7th Biomedical Engineering International Conference, Nanjing, China, 17–20 October 2014; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Gan, H.S.; Sayuti, K.A.; Karim, A.H.A.; Rosidi, R.A.M.; Khaizi, A.S.A. Analysis on semi-automated knee cartilage segmentation model using inter-observer reproducibility: Data from the osteoarthritis initiative. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Bioscience, Biochemistry and Bioinformatics, Kobe, Japan, 21–23 January 2017; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Fripp, J.; Crozier, S.; Warfield, S.K.; Ourselin, S. Automatic segmentation and quantitative analysis of the articular cartilages from magnetic resonance images of the knee. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2009, 29, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balamoody, S.; Williams, T.G.; Waterton, J.C.; Bowes, M.; Hodgson, R.; Taylor, C.J.; Hutchinson, C.E. Comparison of 3T MR scanners in regional cartilage-thickness analysis in osteoarthritis: A cross-sectional multicenter, multivendor study. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2010, 12, R202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Gandhamal, A.; Talbar, S.; Hani, A.F.M. Knee articular cartilage segmentation from MR images: A review. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 2018, 51, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, M.; Prescott, J.; Best, T.; Powell, K.; Jackson, R.; Haq, F.; Gurcan, M. Semi-automated segmentation to assess the lateral meniscus in normal and osteoarthritic knees. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2010, 18, 344–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Jiang, T.; Li, X. Local Region Based Medical Image Segmentation Using J-Divergence Measures. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology 27th Annual Conference, Shanghai, China, 17–18 January 2006; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2006; pp. 7174–7177. [Google Scholar]

- Cashman, P.M.; Kitney, R.I.; Gariba, M.A.; Carter, M.E. Automated techniques for visualization and mapping of articular cartilage in MR images of the osteoarthritic knee: A base technique for the assessment of microdamage and submicro damage. IEEE Trans. Nanobiosci. 2002, 1, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, Y.; Hong, J.; Chen, W. Source-free unsupervised adaptive segmentation for knee joint MRI. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2024, 92, 106028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, B.; Engstrom, C.; Baresic, W.; Fripp, J.; Crozier, S.; Chandra, S.S. Automated anomaly-aware 3D segmentation of bones and cartilages in knee MR images from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Med. Image Anal. 2024, 93, 103089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phan Trung, H.; Nguyen Thiet, S.; Nguyen Trung, T.; Le Tan, L.; Tran Minh, T.; Quan Thanh, T. OsteoGA: An Explainable AI Framework for Knee Osteoarthritis Severity Assessment. In Proceedings of the 12th International Symposium on Information and Communication Technology, Ho Chi Minh, Vietnam, 7–8 December 2023; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 639–646. [Google Scholar]

- Tri Wahyuningrum, R.; Yasid, A.; Jacob Verkerke, G. Deep Neural Networks for Automatic Classification of Knee Osteoarthritis Severity Based on X-ray Images. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Information Technology: IoT and Smart City, Xi’an, China, 25–27 December 2020; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 110–114. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Li, M.; Zhou, Y.; Lu, G.; Zhou, Q. Deep Learning Approach for Anterior Cruciate Ligament Lesion Detection: Evaluation of Diagnostic Performance Using Arthroscopy as the Reference Standard. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2020, 52, 1745–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhao, G.; Kijowski, R.; Liu, F. Deep convolutional neural network for segmentation of knee joint anatomy. Magn. Reson. Med. 2018, 80, 2759–2770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Wen, D.; Xiong, Y.; Gao, Z.; Zhang, P.; Dou, Y. Knee Osteoarthritis Assessment in X-rays Using Global and Local Attention Enhancement and Joint Loss. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Frontiers of Electronics, Information and Computation Technologies, Changsha, China, 21–23 May 2021; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Liu, S.; Zhou, C. Classification of Knee Osteoarthritis Based on Transfer Learning Model and Magnetic Resonance Images. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Machine Learning, Control, and Robotics (MLCR), Suzhou, China, 29–31 October 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 67–71. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, N.; Saeed, M.; Aftab, M.; Mehmood, A.; Ilyas, Q.M. Knee Osteoarthritis Detection And Classification Using Transfer Learning. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Computing and Information Technology (ICCIT), Tabuk, Saudi Arabia, 13–14 September 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 365–369. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, S.; Gaur, A.; Sarathi, M.P. A Simplified Method of Detection and Predicting the Severity of Knee Osteoarthritis. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Computing Communication and Networking Technologies (ICCCNT), Delhi, India, 6–8 July 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, S.B.; Han, H.S.; Lee, M.C.; Kim, H.C.; Ku, Y.; Ro, D.H. Machine learning-based automatic classification of knee osteoarthritis severity using gait data and radiographic images. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 120597–120603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeoh, P.S.Q.; Goh, S.L.; Hasikin, K.; Wu, X.; Lai, K.W. 3D Efficient Multi-Task Neural Network for Knee Osteoarthritis Diagnosis Using MRI Scans: Data From the Osteoarthritis Initiative. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 135323–135333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, T.; Suhail, Z.; Nawaz, Z. Knee Osteoarthritis Detection and Classification Using X-Rays. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 48292–48303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarvamangala, D.; Kulkarni, R.V. Grading of Knee Osteoarthritis Using Convolutional Neural Networks. Neural Process. Lett. 2021, 53, 2985–3009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aladhadh, S.; Mahum, R. Knee osteoarthritis detection using an improved CenterNet with pixel-wise voting scheme. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 22283–22296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harish, H.; Patrot, A.; Bhavan, S.; Gousiya, S.; Livitha, A. Knee Osteoarthritis Prediction Using Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Recent Advances in Information Technology for Sustainable Development (ICRAIS), Manipal, India, 6–7 November 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- Huu, P.N.; Thanh, D.N.; le Thi Hai, T.; Duc, H.C.; Viet, H.P.; Trong, C.N. Detection and Classification Knee Osteoarthritis Algorithm using YOLOv3 and VGG-16 Models. In Proceedings of the 7th National Scientific Conference on Applying New Technology in Green Buildings (ATiGB), Da Nang, Vietnam, 11–12 November 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 31–36. [Google Scholar]

- Antony, J.; McGuinness, K.; O’Connor, N.E.; Moran, K. Quantifying radiographic knee osteoarthritis severity using deep convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR), Cancun, Mexico, 4–8 December 2016; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 1195–1200. [Google Scholar]

- Antonio, P.J.A.; Delmo, J.A.B.; Sevilla, R.V.; Ligayo, M.A.D.; Montesines, D.L. Deep Transfer Network of Knee Osteoarthritis Progression Rate Classification in MR Imaging for Medical Imaging Support System. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Decision Aid Sciences and Applications (DASA), Chiangrai, Thailand, 23–25 March 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 285–289. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, A.; Kumar, V. Enhancing Knee Osteoarthritis Severity Classification using Improved Efficientnet. In Proceedings of the 10th IEEE Uttar Pradesh Section International Conference on Electrical, Electronics and Computer Engineering (UPCON), Gautam Buddha Nagar, India, 1–3 December 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; Volume 10, pp. 1351–1356. [Google Scholar]

- Dharmani, B.C.; Khatri, K. Deep Learning for Knee Osteoarthritis Severity Stage Detection using X-Ray Images. In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on COMmunication Systems & NETworkS (COMSNETS), Bangalore, India, 3–8 January 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 78–83. [Google Scholar]

- Asnidar, A.; Ilham, M.R.; Hidayat, M.T.; Kaswar, A.B.; Arenreng, J.M.P.; Andayani, D.D.; Adiba, F. Application of MobileNetV2 Architecture to Classification of Knee Osteoarthritis Based on X-ray Images. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Advanced Mechatronics, Intelligent Manufacture and Industrial Automation (ICAMIMIA), Surabaya, Indonesia, 14–15 November 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 375–380. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, P.P.; Prasad, S.; Chaudhary, A.K.; Patel, C.K.; Debnath, M. Classification of effusion and cartilage erosion affects in osteoarthritis knee MRI images using deep learning model. In Computer Vision and Image Processing, Proceedings of the 4th International Conference, CVIP 2019, Jaipur, India, 27–29 September 2019; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 373–383. [Google Scholar]

- Sivakumari, T.; Vani, R. Implementation of AlexNet for Classification of Knee Osteoarthritis. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Communication and Electronics Systems (ICCES), Coimbatore, India, 22–24 June 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 1405–1409. [Google Scholar]

- Yildirim, M.; Mutlu, H.B. Automatic detection of knee osteoarthritis grading using artificial intelligence-based methods. Int. J. Imaging Syst. Technol. 2024, 34, e23057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.S.; Yon, C.J.; Lee, D.; Lee, J.J.; Kang, C.H.; Kang, S.B.; Lee, N.K.; Chang, C.B. Assessment of a novel deep learning-based software developed for automatic feature extraction and grading of radiographic knee osteoarthritis. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2023, 24, 869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, R.K.; Sharma, P.K.; Gaj, S.; Sur, A.; Ghosh, P. Knee osteoarthritis severity prediction using an attentive multi-scale deep convolutional neural network. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2024, 83, 6925–6942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mary, C.D.; Rajendran, P.; Sharanyaa, S. Knee Osteoarthritis Severity Prediction Through Medical Image Analysis Using Deep Learning Architectures. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Data Intelligence and Cognitive Informatics, Tirunelveli, India, 27–28 June 2023; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 427–441. [Google Scholar]

- Halim, H.N.A.; Azaman, A. Clustering-Based Support Vector Machine (SVM) for Symptomatic Knee Osteoarthritis Severity Classification. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Biomedical and Bioinformatics Engineering, Kyoto Japan, 10–13 November 2022; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 140–146. [Google Scholar]

- Rehman, A.; Raza, A.; Alamri, F.S.; Alghofaily, B.; Saba, T. Transfer learning-based smart features engineering for osteoarthritis diagnosis from knee X-ray images. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 71326–71338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Virk, S.S.; Jain, V. Detection of osteoarthritis using SVM classifications. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Computing for Sustainable Global Development (INDIACom), New Delhi, India, 16–18 March 2016; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 2997–3002. [Google Scholar]

- Zebari, D.A.; Sadiq, S.S.; Sulaiman, D.M. Knee Osteoarthritis Detection Using Deep Feature Based on Convolutional Neural Network. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Computer Science and Software Engineering (CSASE), Duhok, Iraq, 15–17 March 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 259–264. [Google Scholar]

- Roomi, S.M.M.; Suvetha, S.; Maheswari, P.U.; Suganya, R.; Priya, K. Radon Feature Based Osteoarthritis Severity Assessment. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Signal Processing, Computation, Electronics, Power and Telecommunication (IConSCEPT), Karaikal, India, 25–26 May 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Messaoudene, K.; Harrar, K. Computerized diagnosis of knee osteoarthritis from x-ray images using combined texture features: Data from the osteoarthritis initiative. Int. J. Imaging Syst. Technol. 2024, 34, e23063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahim, A.; Jennane, R.; Riad, R.; Janvier, T.; Khedher, L.; Toumi, H.; Lespessailles, E. A decision support tool for early detection of knee OsteoArthritis using X-ray imaging and machine learning: Data from the OsteoArthritis Initiative. Comput. Med. Imaging Graph. 2019, 73, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.M.; Khoshgoftaar, T.M. Survey on deep learning with class imbalance. J. Big Data 2019, 6, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, S.A.; Strümke, I.; Thambawita, V.; Hammou, M.; Riegler, M.A.; Halvorsen, P.; Parasa, S. On evaluation metrics for medical applications of artificial intelligence. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 5979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Qin, R.; Liu, Z.; Qian, Y.; Ju, X. Optimizing Performance of Image Processing Algorithms on GPUs. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Wireless Communications, Networking and Applications, Berlin, Germany, 17–19 December 2021; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 936–943. [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary, K.; DeCost, B.; Chen, C.; Jain, A.; Tavazza, F.; Cohn, R.; Park, C.W.; Choudhary, A.; Agrawal, A.; Billinge, S.J.; et al. Recent advances and applications of deep learning methods in materials science. npj Comput. Mater. 2022, 8, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Sun, Y.; Lin, J.; Li, L.; Feng, T.; Yin, S. The synergy of seeing and saying: Revolutionary advances in multi-modality medical vision-language large models. Artif. Intell. Sci. Eng. 2025, 1, 79–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, L.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, H.; Qiao, X.; Feng, T.; Luo, H.; Zhao, Y. Vision-Language Models in medical image analysis: From simple fusion to general large models. Inf. Fusion 2025, 118, 102995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Publisher | Total Studies Found | Initial Selection | Final Selection |

|---|---|---|---|

| IEEE | 282 | 143 | 20 |

| Springer | 1381 | 49 | 19 |

| Elsevier | 194 | 28 | 6 |

| Wiley | 1044 | 27 | 6 |

| ACM | 182 | 12 | 2 |

| Others | 525 | 57 | 12 |

| Activation Function | Formula |

|---|---|

| SoftMax | |

| Sigmoid | |

| Tanh | |

| ReLU | |

| Leaky ReLU |

| Year | Architecture | Key Features | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1998 | LeNet [49] | The initial successful implementation of CNNs involved five alternating layers of convolution and pooling, utilizing tanh or sigmoid activation functions | Recognizing handwritten and machine-printed characters, Face Recognition [50] |

| 2012 | AlexNet [51] | Uses ReLU activation function, use of dropout layers, trained on GPUs | Large-scale image recognition, surface defect recognition [52] |

| 2013 | ZFNet [53] | Less number of filters with reduced stride, retains more pixel information, visualization of features | Classification of ImageNet data, object classification [54] |

| 2014 | VGGNet [36] | Deeper networks with smaller filters, same depth of convolutional layers, has multiple configurations | Image classification, object detection, medical imaging, surveillance [55] |

| 2014 | GoogLeNet [56] | Use of Inception Module, more efficient computation and deeper networks, multiple version of inception | Image segmentation, transfer learning, video analysis, medical imaging [57] |

| 2014 | R-CNN [58] | Segmentation into regions of interest, generation of fixed length feature vector, use of bounding boxes and coordinates | Object detection, visual search, document analysis, ocr, autonomous vehicles [59] |

| 2015 | ResNet [37] | Use of skip connections to train deeper networks, overcome vanishing gradient problem, global average pooling after residual blocks | Semantic segmentation, medical image analysis, transfer learning, facial recognition, edge computing [60] |

| 2015 | YOLO [38] | Single forward pass and detection, divides image into grid cells, uses bounding boxes for feature detection | Security and surveillance, object tracking, drone applications [61] |

| 2016 | DenseNet [39] | Use of dense blocks where each layer is connected to every other layer in feed-forward fashion, feature reuse | Fine-grained recognition, object recognition in unstructured environments [50] |

| 2017 | MobileNet [40] | For mobile and embedded vision applications, Use depth-wise separable convolutions, reduced model size and complexity | Mobile and embedded vision applications, real-time object detection, inspection and defect identification [62] |

| 2018 | EfficientNet [41] | Uses compound scaling method, efficient architectural design with MBConv blocks, SE optimization, and the use of Swish activation function | Image classification, object detection and localization, and semantic segmentation [63] |

| 2018 | NASNet [64] | Use of neural architecture search and reinforcement learning, facilitates transferability and scalability | Medical imaging, autonomous vehicles, and industrial quality control [65] |

| 2022 | ConvNeXt [66] | It integrates vision transformers, layer normalization, and the Gaussian Error Linear Unit (GELU) activation function | Pedestrian and traffic sign detection, visual content search and digital asset management [67] |

| Category | Technique | Key Details | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Augmentation | Geometric transformations | Rotation (±3°), flipping, translation, scaling | [5,94,95,104,112,124] |

| Intensity-based augmentation | Brightness, contrast, gamma correction, color jitter | [5,117,124] | |

| Class balancing | Oversampling/stratified sampling of minority KL grades | [94,104,106,124] | |

| Noise injection | Gaussian noise addition | [117] | |

| Preprocessing | Histogram equalization | Global HE or BPHE | [89,110,119,122] |

| CLAHE | Clip limit ≈ 2.0, tile grid | [104,105,112,117] | |

| Noise filtering | Median, adaptive median, Gaussian, anisotropic filters | [104,105,107,110,122] | |

| Normalization | Intensity scaling; pixel spacing normalization | [90,92,94,98,106,116] | |

| Resizing/cropping | Fixed input size; border removal | [89,104,105,110] | |

| Grayscale conversion | 16-bit to 8-bit grayscale (DICOM) | [92,94,110] | |

| ROI Handling | Knee joint localization | Landmark detection using BoneFinder/FCN | [98,117,125] |

| Bounding box detection | Template matching or DL-based (YOLO, Faster R-CNN) | [92,94,95,126,127] | |

| ROI cropping | Fixed-size patches around joint center | [89,98,105,117] | |

| Region proposal networks | RPN-based ROI extraction | [94,106,127] | |

| BPHE: Brightness-Preserving Histogram Equalization; RPN: Region Proposal Network; FCN: Fully Convolutional Network. | |||

| Reference and Year | Input Data Modality | Approach Used | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| [130], 2014 | X-ray | Medial, Lateral, and Minimum Joint Space Width (JSW) measured manually | Middle part of the condyles from narrowest point of joint used |

| [135], 2010 | MRI | Cartilage segmented manually from sagittal 3D sequences; Uses endpoint segmentation software with livewire algorithm | Quality control performed by musculoskeletal radiologists |

| [131], 2009 | X-ray | Manual joint segmentation; Software to determine joint space width boundary; Automatically identified medial subchondral bone to be used in Fractal Signature Analysis (FSA) | Six selected initialization points: tibial spine, lateral tibia, medial tibial, lateral tibial spine, medial femur, lateral femur |

| Reference and Year | Input Data Modality | Approach Used | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| [133], 2017 | X-ray | Random walks model for simultaneous label segmentation | Four labels: femoral, tibial, patella, background |

| [132], 2014 | MRI | Active Shape Models (ASM) for semi-automatic segmentation | Articular cartilage segmented at distal femur |

| [137], 2010 | MRI | Seed point within meniscus; Gaussian fit threshold; Conditional dilation; Post-processing refinement | Works for normal and degenerative menisci |

| [138], 2006 | X-ray | Region homogeneity based on intensity; Energy function to minimize dissimilarity; Iterative mean/variance update | Manual initialization with automatic computation |

| [139], 2002 | MRI | Semi-automated segmentation and cartilage thickness mapping | Uses 3D gradient echo MR images |

| Reference and Year | Input Data Modality | Approach Used | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| [140], 2024 | MRI | Batch normalization and augmented entropy minimization; Refined using voting strategy | Uncertainty-aware pseudo supervision to boost performance |

| [141], 2024 | MRI | Semantic segmentation of bones and cartilage; Anomaly aware segmentation | Improves bone anomaly detection |

| [142], 2023 | X-ray | Tibia and femur segmentation using YOLOv8 | OsteoGA generates images for segmentation |

| [5], 2022 | X-ray | YOLOv3-tiny to segment ROI | Same model used for classification |

| [106], 2022 | X-ray | Faster RCNN to detect ROI; ResNet-50 for feature extraction | RPN generates region proposals |

| [128], 2020 | X-ray | Locate subchondral bone; Superpixel segmentation using SLIC | LBP evaluates sub-regions |

| [129], 2011 | X-ray | Two-stage segmentation using CLAHE, template matching, and COM | Accuracy of 100% |

| [134], 2009 | MRI | Bone statistical shape model with cartilage thickness | Femur, tibia, patella segmented |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Rani, S.; Rout, A.; Soni, P.; Gupta, M.; Kumar, N.; Kumar, K. Review of CNN-Based Approaches for Preprocessing, Segmentation and Classification of Knee Osteoarthritis. Diagnostics 2026, 16, 461. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16030461

Rani S, Rout A, Soni P, Gupta M, Kumar N, Kumar K. Review of CNN-Based Approaches for Preprocessing, Segmentation and Classification of Knee Osteoarthritis. Diagnostics. 2026; 16(3):461. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16030461

Chicago/Turabian StyleRani, Sudesh, Akash Rout, Priyanka Soni, Mayank Gupta, Naresh Kumar, and Karan Kumar. 2026. "Review of CNN-Based Approaches for Preprocessing, Segmentation and Classification of Knee Osteoarthritis" Diagnostics 16, no. 3: 461. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16030461

APA StyleRani, S., Rout, A., Soni, P., Gupta, M., Kumar, N., & Kumar, K. (2026). Review of CNN-Based Approaches for Preprocessing, Segmentation and Classification of Knee Osteoarthritis. Diagnostics, 16(3), 461. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16030461