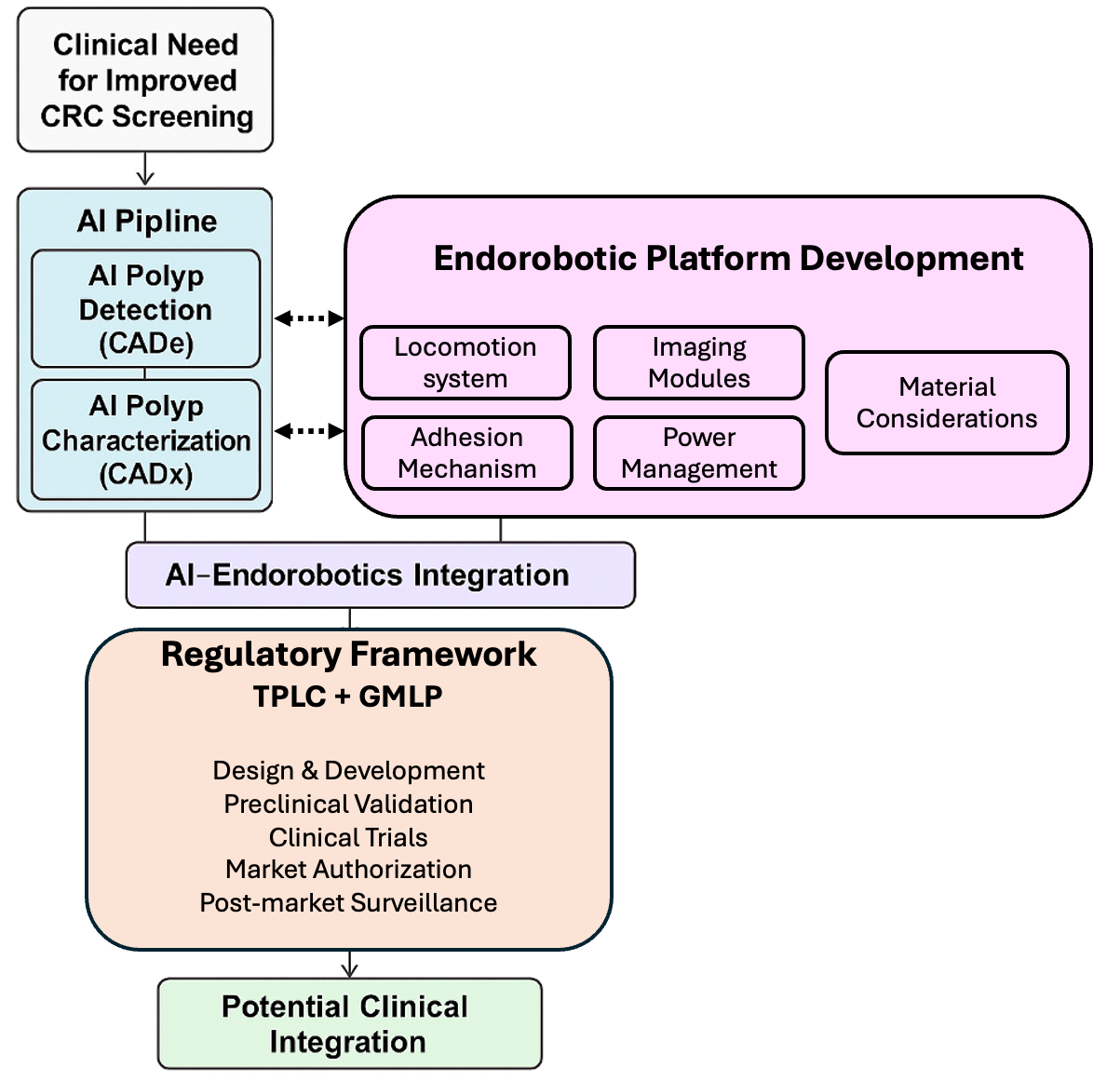

Emerging Endorobotic and AI Technologies in Colorectal Cancer Screening: A Review of Design, Validation, and Translational Pathways

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Technological Innovations in Colorectal Cancer Screening

2.1. Artificial Intelligence in Colorectal Cancer Screening

2.1.1. AI for Polyp Detection (CADe)

2.1.2. AI for Polyp Characterization (CADx)

2.1.3. AI in CT Colonography (Virtual Colonoscopy)

| Feature | CADe (Detection) [32,42,51] | CADx (Characterization) [44,51] | AI in CT Colonography (CTC) [50,52,53] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Real-time detection of polyps during colonoscopy. | Real-time histologic/optical classification of polyps (“virtual histology”) | Non-invasive identification of Colorectal lesions from CT imaging. |

| Key Metrics | Sensitivity up to ~95–100% in image/ polyp-level validation and real-time testing (e.g., GI Genius–type systems) | Negative predictive value (NPV) up to 97% for diminutive polyps (e.g., ENDOANGEL-CPS). | CTC polyp characterization reach AUC 0.83–0.91 with sensitivities ~80–82% and specificities ~69–85% |

| Clinical Benefit | Increases adenoma detection rate (ADR); reduces missed lesions. | Supports “resect and discard” and “diagnose and leave” strategies, potentially lowering pathology workload. | Provides an option for patients unwilling or unable to undergo colonoscopy. |

| Limitations | High false-positive rate; strongest effect on diminutive/non-advanced adenomas | Model bias; limited accuracy for sessile/flat lesions and external generalizability concerns | Involves ionizing radiation; CT colonography positive (and AI-flagged) findings still require colonoscopy for biopsy/resection |

| Regulatory Status | FDA-approved (e.g., GI Genius). | Mostly investigational or early clinical; few systems approaching regulatory pathways | In proof-of-concept and validation phases; no FDA-approved |

| Readiness Level | Available for clinical use in select settings. | Early-stage clinical trials and pilot implementations; limited routine uptake | Experimental/adjunct only; requires further validation. |

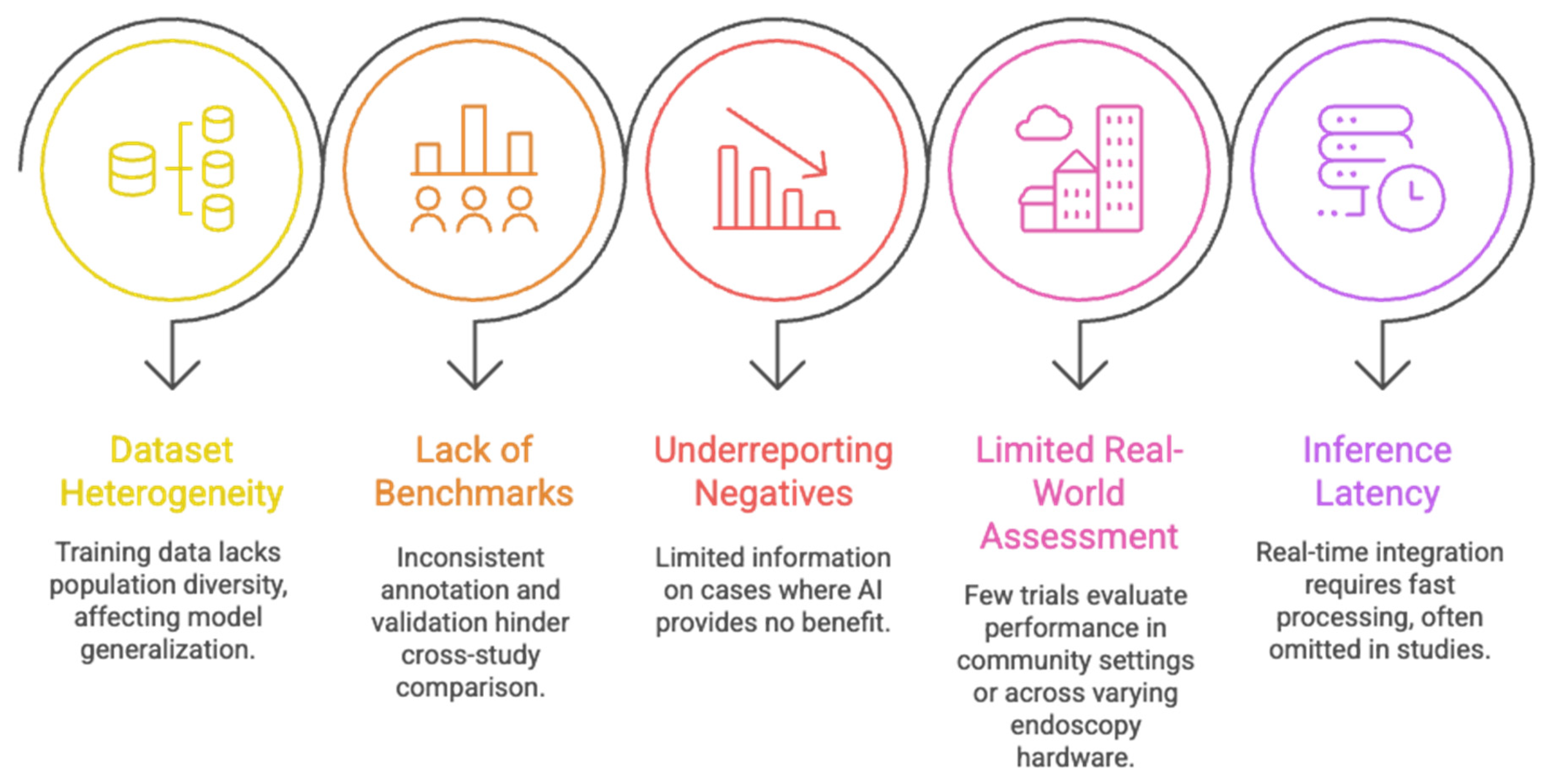

2.1.4. Limitations of Current AI Models

2.1.5. Regulatory Landscape for AI in CRC Screening

2.2. Robotic-Assisted Colonoscopy Platforms

2.2.1. Clinical-Ready and Near-Clinical Platforms

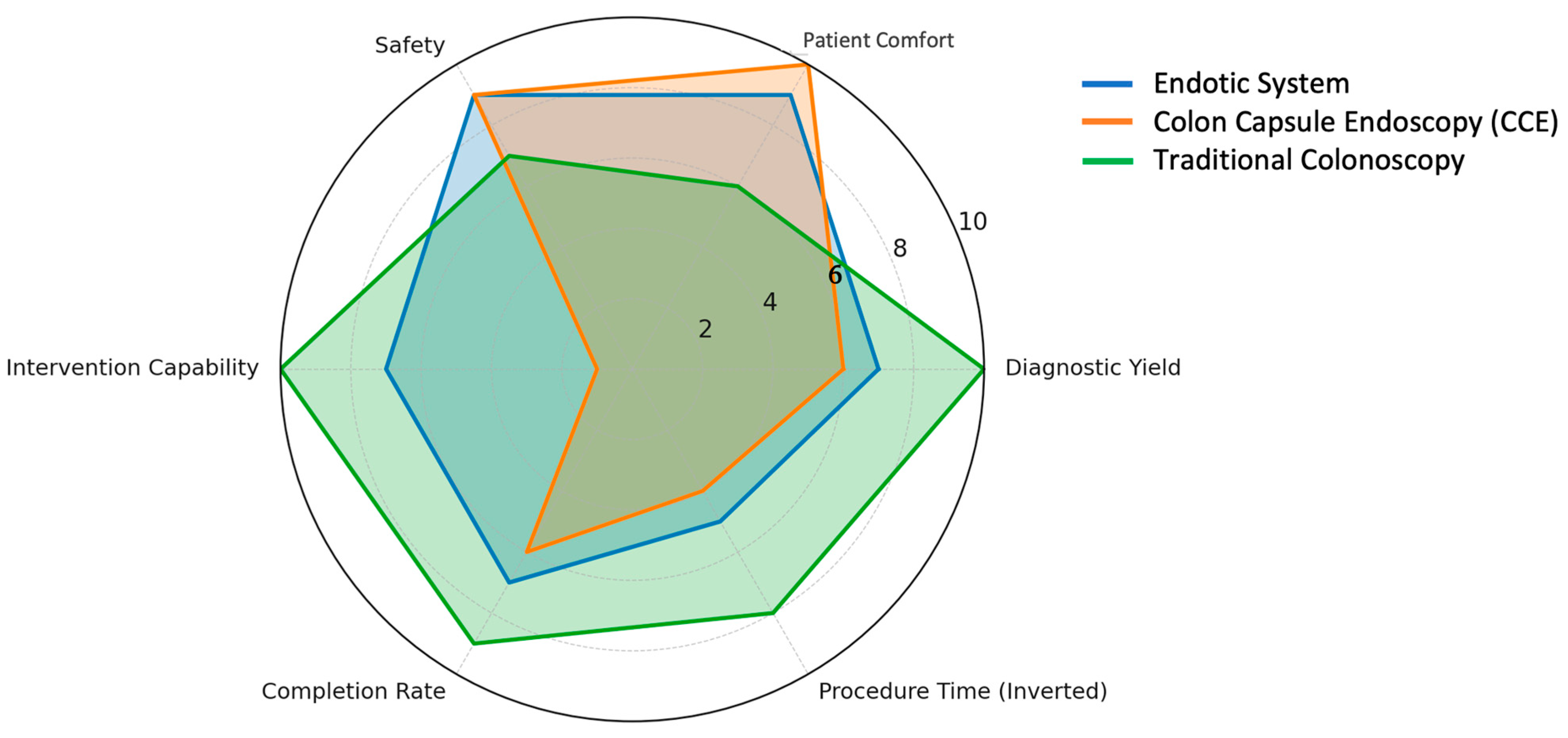

Endotics System (E-Worm)

Colon Capsule Endoscopy (CCE)

| Feature | Endotics System (E-Worm) [57,58,59] | Colon Capsule Endoscopy (CCE) [56,60] | Traditional Colonoscopy [16,61] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Invasiveness | Minimally invasive; self-propelled soft probe. | Non-invasive; swallowed capsule. | Invasive; requires endoscope insertion. |

| Interventional Capability | Yes—allows biopsy and polyp removal. | No—diagnostic only. | Yes—biopsy, polypectomy, and therapeutic procedures. |

| Patient Comfort | High; no sedation required. | Very high; no sedation or manipulation. | Moderate; sedation typically required. |

| Completion Rate | ~82% cecal intubation. | Variable (~70% in some studies). | >90% with experienced endoscopists. |

| Diagnostic Accuracy | ~93% for polyps ≥6 mm. | ~87% sensitivity, 88% specificity for ≥6 mm polyps. | >95% for polyps >10 mm. |

| Reusability | Single-use disposable. | Single-use capsule. | Reusable (requires reprocessing). |

| Procedure Duration | ~45 min. | 10–14 h (transit), plus 30–60 min review. | 30–60 min. |

| Safety Profile | Excellent; minimal mucosal trauma, no sedation risk. | Very safe; rare capsule retention. | Generally safe, but sedation-related risks. |

| Power Source | Tethered. | Internal battery. | Tethered/manual. |

| Current Limitations | Sensitive to bowel prep; slower procedure. | No therapeutic capability; prolonged excretion time. | Discomfort, sedation risks, high operator skill requirement. |

2.2.2. CAD Clinical Readiness

2.2.3. Challenges in Robotic-Assisted Colonoscopy

3. Engineering Design Framework for Endorobotic Colonoscopy Systems

3.1. Endorobotic Locomotion Systems and Safety Challenges

- I. Peristalsis locomotion

- II. Ambulatory (Legged) Locomotion

- III. Wheeled/Rolling Locomotion

- IV. Immobile (Passive) platform

- V. AI/ML-Assisted Navigation and Control in GI Endorobotics

3.2. Adhesion Mechanisms and Mucosal Safety Considerations

- I. Suction adhesion

- II. Microhooks and Barbs

- III. Adhesive pads

- IV. Magnetic systems

| Adhesion Mechanism | Grip Strength | Tissue Safety | Reversibility | External Dependency | Translational Implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suction | Moderate | Moderate (risk of mucosal trauma with prolonged use) | High | No | Simple and effective; widely used but limited by potential tissue injury and air leakage in dynamic environments. |

| Microhooks | High | Low (risk of mucosal penetration) | Moderate | No | Provides strong anchoring but poor biocompatibility; limited clinical feasibility. |

| Adhesive Pads | Low–Moderate | High | High | No | Biocompatible and reversible; promising for short-term adhesion but limited durability in wet/mucosal environments. |

| Magnetic Coupling | Moderate | Very High | High | Yes (requires external magnetic field/guidance system) | Enables atraumatic adhesion with excellent safety; external hardware is a barrier to portability and scalability. |

3.3. Imaging and Sensing Constraints in Endorobotic Platforms

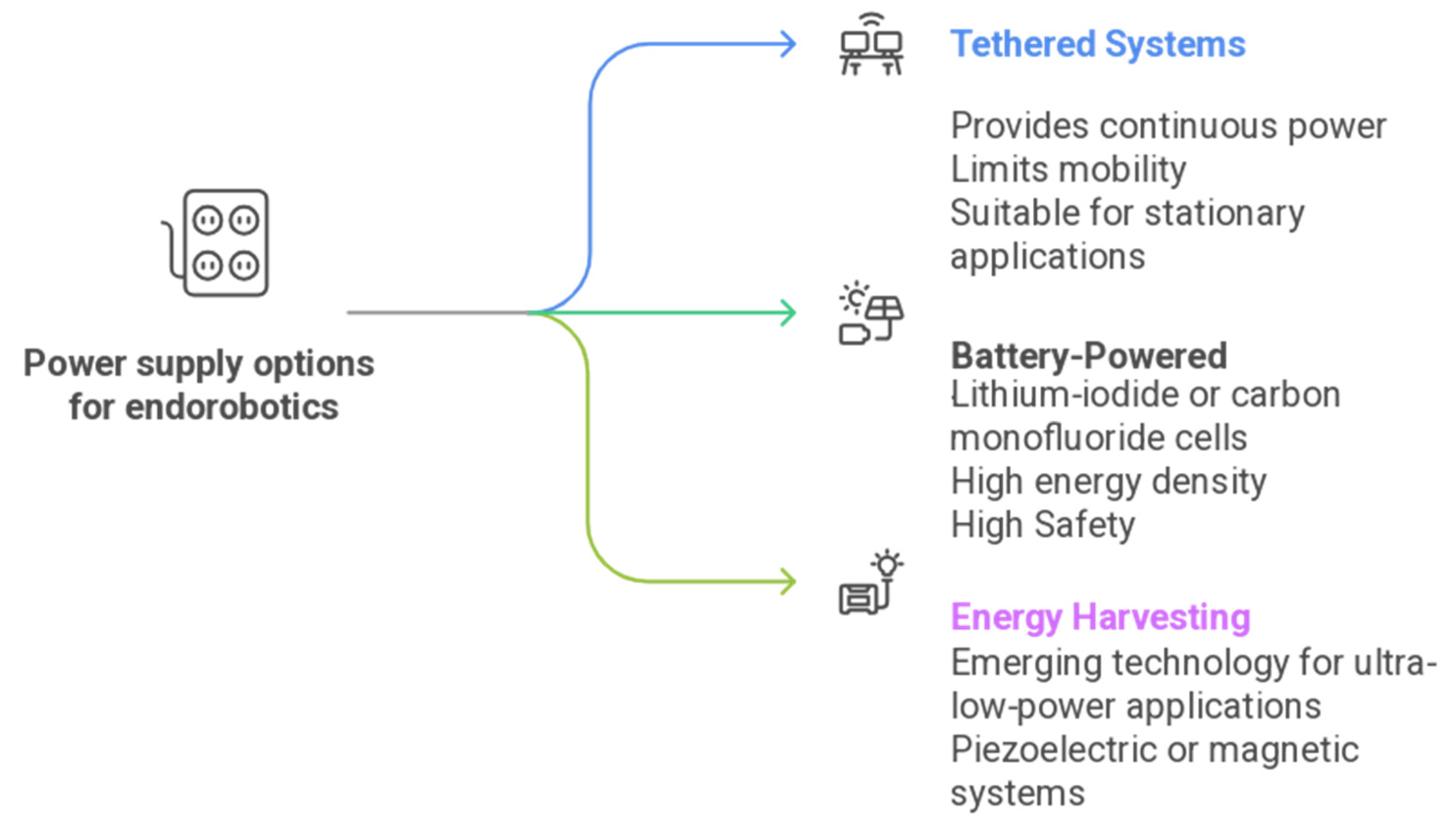

3.4. Power Management and System Stability

- Embedded-system optimization and hardware acceleration.

3.5. Material Considerations

3.5.1. Silicone Elastomers

3.5.2. Thermoplastic Polyurethanes (TPUs)

4. Regulatory Alignment and Translational Validation

4.1. System-Level Integration and Trade-Offs

4.2. Regulatory Alignment and Translational Validation Framework

- (i)

- Evidence level, ranging from in silico and benchtop studies to preclinical models and early human feasibility trials;

- (ii)

- Validation stage, including reported data on mucosal safety, procedural reliability, and reproducibility;

- (iii)

- Technology maturity considerations, such as workflow integration, sterility and reprocessing feasibility, manufacturability, regulatory progress, and compatibility with existing endoscopy infrastructure.

| TPLC Stage | Regulatory/Validation Activities | Corresponding GMLP Principles |

|---|---|---|

| Design & Development | Initial risk analysis; user-centered engineering; defining intended use; needs-driven innovation to address clinical gaps. | Principle 1—Multidisciplinary expertise across lifecycle. Principle 5—Model design is tailored to intended use. Principle 3—Data representativeness planned at this stage. |

| Preclinical Validation | In silico testing, bench testing, and in vivo animal studies to confirm basic safety, reliability, and functional performance. | Principle 2—Good software engineering & security practices. Principle 4—Use reference datasets for model training and evaluation |

| Clinical Trials | Human studies assessing safety (e.g., mucosal trauma), usability, workflow integration, diagnostic performance, ADR, false-positive rate, and real-world variability. | Principle 7—Human–AI team performance. Principle 8—Testing under clinically relevant conditions. Principle 3—Representative patient population |

| Market Authorization | Regulatory submissions: FDA 510(k), De Novo, PMA; EU MDR documentation; benefit–risk assessment; labeling and transparency requirements. | Principle 10—Clear, essential information provided to users. Principle 2—Software documentation & security. Principle 6—Intended use alignment. |

| Postmarket Surveillance | Continuous real-world monitoring; incident reporting; drift detection; version control; re-training governance; recalls or updates if needed. | Principle 8—Provide clear, informative user information Principle 9—Ongoing monitoring & re-training risk management. Principle 10—Transparency for updates. |

5. Conclusions and Future Priorities

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Cancer Observatory. 2021. Available online: https://gco.iarc.fr/en (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Luo, Z.; Bradley, C.J.; Dahman, B.A.; Gardiner, J.C. Colon cancer treatment costs for Medicare and dually eligible beneficiaries. Health Care Financ. Rev. 2010, 31, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Van Erning, F.N.; Van Steenbergen, L.N.; Lemmens, V.E.P.P.; Rutten, H.J.T.; Martijn, H.; Van Spronsen, D.J.; Janssen-Heijnen, M.L.G. Conditional survival for long-term colorectal cancer survivors in the Netherlands: Who do best? Eur. J. Cancer (Oxf. Engl. 1990) 2014, 50, 1731–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaukat, A.; Kahi, C.J.; Burke, C.A.; Rabeneck, L.; Sauer, B.G.; Rex, D.K. ACG Clinical Guidelines: Colorectal Cancer Screening 2021. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 116, 458–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorgun, E.; Benlice, C.; Church, J.M. Does Cancer Risk in Colonic Polyps Unsuitable for Polypectomy Support the Need for Advanced Endoscopic Resections? J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2016, 223, 478–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponugoti, P.L.; Cummings, O.W.; Rex, D.K. Risk of cancer in small and diminutive colorectal polyps. Digestive and Liver Disease. Off. J. Ital. Soc. Gastroenterol. Ital. Assoc. Study Liver 2017, 49, 34–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rembacken, B.; Hassan, C.; Riemann, J.F.; Chilton, A.; Rutter, M.; Dumonceau, J.M.; Omar, M.; Ponchon, T. Quality in screening colonoscopy: Position statement of the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE). Endoscopy 2012, 44, 957–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montminy, E.M.; Jang, A.; Conner, M.; Karlitz, J.J. Screening for Colorectal Cancer. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 104, 1023–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gimeno-García, A.Z.; Quintero, E. Role of colonoscopy in colorectal cancer screening: Available evidence. Best. Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2023, 66, 101838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rex, D.K.; Schoenfeld, P.S.; Cohen, J.; Pike, I.M.; Adler, D.G.; Fennerty, M.B.; Lieb, J.G.; Park, W.G.; Rizk, M.K.; Sawhney, M.S.; et al. Quality indicators for colonoscopy. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2015, 81, 31–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tontini, G.E.; Prada, A.; Sferrazza, S.; Ciprandi, G.; Vecchi, M. The unmet needs for identifying the ideal bowel preparation. JGH Open 2021, 5, 1135–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLachlan, J.H.; Locarnini, S.; Cowie, B.C. Estimating the global prevalence of hepatitis B. Lancet 2015, 386, 1515–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.M.N.; Hunleth, J.; Rolf, L.; Maki, J.; Lewis-Thames, M.; Oestmann, K.; James, A.S. Distance and Transportation Barriers to Colorectal Cancer Screening in a Rural Community. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2023, 14, 21501319221147126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddingham, W.; Kamran, U.; Kumar, B.; Trudgill, N.J.; Tsiamoulos, Z.P.; Banks, M. Complications of colonoscopy: Common and rare—Recognition, assessment and management. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2023, 10, e001193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLachlan, S.-A.; Clements, A.; Austoker, J. Patients’ experiences and reported barriers to colonoscopy in the screening context—A systematic review of the literature. Patient Educ. Couns. 2012, 86, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hann, A.; Troya, J.; Fitting, D. Current status and limitations of artificial intelligence in colonoscopy. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2021, 9, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASGE AI Task Force; Parasa, S.; Berzin, T.; Leggett, C.; Gross, S.; Repici, A.; Ahmad, O.F.; Chiang, A.; Coelho-Prabhu, N.; Cohen, J.; et al. Consensus statements on the current landscape of artificial intelligence applications in endoscopy, addressing roadblocks, and advancing artificial intelligence in gastroenterology. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2025, 101, 2–9.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elamin, S.; Johri, S.; Rajpurkar, P.; Geisler, E.; Berzin, T.M. From data to artificial intelligence: Evaluating the readiness of gastrointestinal endoscopy datasets. J. Can. Assoc. Gastroenterol. 2025, 8, S81–S86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papachrysos, N.; Smedsrud, P.H.; Ånonsen, K.V.; Berstad, T.J.D.; Espeland, H.; Petlund, A.; Hedenström, P.J.; Halvorsen, P.; Varkey, J.; Hammer, H.L.; et al. A comparative study benchmarking colon polyp with computer-aided detection (CADe) software. DEN Open 2025, 5, e70061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, C.; Spadaccini, M.; Iannone, A.; Maselli, R.; Jovani, M.; Chandrasekar, V.T.; Antonelli, G.; Yu, H.; Areia, M.; Dinis-Ribeiro, M.; et al. Performance of artificial intelligence in colonoscopy for adenoma and polyp detection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2021, 93, 77–85.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lou, S.; Du, F.; Song, W.; Xia, Y.; Yue, X.; Yang, D.; Cui, B.; Liu, Y.; Han, P. Artificial intelligence for colorectal neoplasia detection during colonoscopy: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. EClinicalMedicine 2023, 66, 102341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Maheshwari, M.; Aleem, S.; Batool, Z.; Lal, A.; Syed, S.; Daterdiwala, N.F.; Memon, H.F.; Azeem, J.; Qamari, S.M.H.; et al. Novel Artificial Intelligence Systems in Detecting Adenomas in Colonoscopy: A Systemic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Clin. Transl. Gastroenterol. 2025, 16, e00904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, B.; Singh, J.; González, J.F.S.; Zalmai, S.; Ahmed, A.; Padekar, H.D.; Eichemberger, M.R.; Abdallah, A.I.; Ahamed, I.; Nazir, Z. A Narrative Review on the Role of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Colorectal Cancer Management. Cureus 2025, 17, e79570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsala, A.; Tsalikidis, C.; Pitiakoudis, M.; Simopoulos, C.; Tsaroucha, A.K. Artificial Intelligence in Colorectal Cancer Screening, Diagnosis and Treatment. A New Era. Curr. Oncol. 2021, 28, 1581–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, K.; Wang, Y.; Qu, R.; Yang, Q.; Luo, R.; Jiang, Z.; Wang, H.; Fu, W. Comprehensive application of artificial intelligence in colorectal cancer: A review. IScience 2025, 28, 112980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Aravind, N.; Gillani, T.; Kumar, D. Artificial intelligence breakthrough in diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of colorectal cancer—A comprehensive review. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2025, 101, 107205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Wang, S.; Pan, P.; Xia, T.; Chang, X.; Yang, X.; Guo, L.; Meng, Q.; Yang, F.; Qian, W.; et al. Magnitude, Risk Factors, and Factors Associated With Adenoma Miss Rate of Tandem Colonoscopy: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2019, 156, 1661–1674.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Esparrach, G.; Bernal, J.; López-Cerón, M.; Córdova, H.; Sánchez-Montes, C.; Rodríguez De Miguel, C.; Sánchez, F.J. Exploring the clinical potential of an automatic colonic polyp detection method based on the creation of energy maps. Endoscopy 2016, 48, 837–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Berzin, T.M.; Glissen Brown, J.R.; Bharadwaj, S.; Becq, A.; Xiao, X.; Liu, P.; Li, L.; Song, Y.; Zhang, D.; et al. Real-time automatic detection system increases colonoscopic polyp and adenoma detection rates: A prospective randomised controlled study. Gut 2019, 68, 1813–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Liu, X.; Berzin, T.M.; Glissen Brown, J.R.; Liu, P.; Zhou, C.; Lei, L.; Li, L.; Guo, Z.; Lei, S.; et al. Effect of a deep-learning computer-aided detection system on adenoma detection during colonoscopy (CADe-DB trial): A double-blind randomised study. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 5, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repici, A.; Badalamenti, M.; Maselli, R.; Correale, L.; Radaelli, F.; Rondonotti, E.; Ferrara, E.; Spadaccini, M.; Alkandari, A.; Fugazza, A.; et al. Efficacy of Real-Time Computer-Aided Detection of Colorectal Neoplasia in a Randomized Trial. Gastroenterology 2020, 159, 512–520.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudo, S.E.; Misawa, M.; Mori, Y.; Hotta, K.; Ohtsuka, K.; Ikematsu, H.; Saito, Y.; Takeda, K.; Nakamura, H.; Ichimasa, K.; et al. Artificial Intelligence-assisted System Improves Endoscopic Identification of Colorectal Neoplasms. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 18, 1874–1881.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira-Rodríguez, A.; Domínguez-Carbajales, R.; López-Fernández, H.; Iglesias, Á.; Cubiella, J.; Fdez-Riverola, F.; Reboiro-Jato, M.; Glez-Peña, D. Deep Neural Networks approaches for detecting and classifying colorectal polyps. Neurocomputing 2021, 423, 721–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira-Rodríguez, A.; Reboiro-Jato, M.; Glez-Peña, D.; López-Fernández, H. Performance of Convolutional Neural Networks for Polyp Localization on Public Colonoscopy Image Datasets. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchese Aizenman, G.; Salvagnini, P.; Cherubini, A.; Biffi, C. Assessing clinical efficacy of polyp detection models using open-access datasets. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1422942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimeno-García, A.Z.; Hernández-Pérez, A.; Nicolás-Pérez, D.; Hernández-Guerra, M. Artificial Intelligence Applied to Colonoscopy: Is It Time to Take a Step Forward? Cancers 2023, 15, 2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houwen, B.B.S.L.; Nass, K.J.; Vleugels, J.L.A.; Fockens, P.; Hazewinkel, Y.; Dekker, E. Comprehensive review of publicly available colonoscopic imaging databases for artificial intelligence research: Availability, accessibility, and usability. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2023, 97, 184–199.e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Gao, J.; Liu, L.; Yin, M.; Lin, J.; Xu, C.; Xu, C.; Zhu, J. Public Imaging Datasets of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy for Artificial Intelligence: A Review. J. Digit. Imaging 2023, 36, 2578–2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.A.; Iinuma, G.; Saito, Y.; Zhang, J.; Halligan, S. CT colonography: Computer-aided detection of morphologically flat T1 colonic carcinoma. Eur. Radiol. 2008, 18, 1666–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, D.; Wu, L.; Zhang, J.; Mu, G.; Shen, L.; Liu, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, W.; An, P.; Huang, X.; et al. Detection of colorectal adenomas with a real-time computer-aided system (ENDOANGEL): A randomised controlled study. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 5, 352–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Chen, B.; Cheng, D.; Liao, F.; Tan, T.; Xu, Q.; Liu, Z.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, C.; et al. A real-time deep learning-based system for colorectal polyp size estimation by white-light endoscopy: Development and multicenter prospective validation. Endoscopy 2023, 56, 260–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zachariah, R.; Samarasena, J.; Luba, D.; Duh, E.; Dao, T.; Requa, J.; Ninh, A.; Karnes, W. Prediction of Polyp Pathology Using Convolutional Neural Networks Achieves “resect and Discard” Thresholds. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 115, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, Y.; Kudo, S.E.; Misawa, M.; Saito, Y.; Ikematsu, H.; Hotta, K.; Ohtsuka, K.; Urushibara, F.; Kataoka, S.; Ogawa, Y.; et al. Real-Time Use of Artificial Intelligence in Identification of Diminutive Polyps During Colonoscopy: A Prospective Study. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, M.F.; Chapados, N.; Soudan, F.; Oertel, C.; Pérez, M.L.; Kelly, R.; Iqbal, N.; Chandelier, F.; Rex, D.K. Real-time differentiation of adenomatous and hyperplastic diminutive colorectal polyps during analysis of unaltered videos of standard colonoscopy using a deep learning model. Gut 2019, 68, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oukdach, Y.; Garbaz, A.; Kerkaou, Z.; El Ansari, M.; Koutti, L.; El Ouafdi, A.F.; Salihoun, M. UViT-Seg: An Efficient ViT and U-Net-Based Framework for Accurate Colorectal Polyp Segmentation in Colonoscopy and WCE Images. J. Imaging Inform. Med. 2024, 37, 2354–2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lijin, P.; Ullah, M.; Vats, A.; Cheikh, F.A.; Santhosh Kumar, G.; Nair, M.S. PolySegNet: Improving polyp segmentation through swin transformer and vision transformer fusion. Biomed. Eng. Lett. 2024, 14, 1421–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayana, G.; Barki, H.; Choe, S.W. Pathological Insights: Enhanced Vision Transformers for the Early Detection of Colorectal Cancer. Cancers 2024, 16, 1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valanarasu, J.M.J.; Oza, P.; Hacihaliloglu, I.; Patel, V.M. Medical Transformer: Gated Axial-Attention for Medical Image Segmentation. In Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2021; de Brujine, M., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 12901, Lecture Notes in Computer Science. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosu, S.; Wesp, P.; Graser, A.; Maurus, S.; Schulz, C.; Knösel, T.; Cyran, C.C.; Ricke, J.; Ingrisch, M.; Kazmierczak, P.M. Machine learning-based differentiation of benign and premalignant colorectal polyps detected with CT colonography in an asymptomatic screening population: A proof-of-concept study. Radiology 2021, 299, 326–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, C.; Spadaccini, M.; Mori, Y.; Foroutan, F.; Facciorusso, A.; Gkolfakis, P.; Tziatzios, G.; Triantafyllou, K.; Antonelli, G.; Khalaf, K.; et al. Real-Time Computer-Aided Detection of Colorectal Neoplasia During Colonoscopy: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann. Intern. Med. 2023, 176, 1209–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hegde, N.; Shishir, M.; Shashank, S.; Dayananda, P.; Latte, M.V. A Survey on Machine Learning and Deep Learning-based Computer-Aided Methods for Detection of Polyps in CT Colonography. Curr. Med. Imaging 2020, 17, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, S.; Nagata, K.; Utano, K.; Nozu, S.; Yasuda, T.; Takabayashi, K.; Hirayama, M.; Togashi, K.; Ohira, H. Development and validation of computer-aided detection for colorectal neoplasms using deep learning incorporated with computed tomography colonography. BMC Gastroenterol. 2025, 25, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spadaccini, M.; Marco, A.D.; Franchellucci, G.; Sharma, P.; Hassan, C.; Repici, A. Discovering the first US FDA-approved computer-aided polyp detection system. Future Oncol. 2022, 18, 1405–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.G. Painless colonoscopy: Available techniques and instruments. Clin. Endosc. 2016, 49, 444–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismail, M.S.; Murphy, G.; Semenov, S.; McNamara, D. Comparing Colon Capsule Endoscopy to colonoscopy; a symptomatic patient’s perspective. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022, 22, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, B.P.M.; Chiu, P.W.Y. Application of robotics in gastrointestinal endoscopy: A review. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 22, 1811–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tumino, E.; Sacco, R.; Bertini, M.; Bertoni, M.; Parisi, G.; Capria, A. Endotics system vs colonoscopy for the detection of polyps. World J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 16, 5452–5456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosentino, F.; Tumino, E.; Passoni, G.R.; Morandi, E.; Capria, A. Functional evaluation of the Endotics System, a new disposable self-propelled robotic colonoscope: In vitro tests and clinical trial. Int. J. Artif. Organs 2009, 32, 517–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cash, B.D.; Fleisher, M.R.; Fern, S.; Rajan, E.; Haithcock, R.; Kastenberg, D.M.; Pound, D.; Papageorgiou, N.P.; Fernández-Urién, I.; Schmelkin, I.J.; et al. Multicentre, prospective, randomised study comparing the diagnostic yield of colon capsule endoscopy versus CT colonography in a screening population (the TOPAZ study). Gut 2021, 70, 2115–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcaide, O.J.; Pearson, L.; Mark, E.R. Design, Modeling and Control of a SMA-Actuated Biomimetic Robot with Novel Functional Skin. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Singapore, 29 May–3 June 2017; pp. 4338–4345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumino, E.; Visaggi, P.; Bolognesi, V.; Ceccarelli, L.; Lambiase, C.; Coda, S.; Premchand, P.; Bellini, M.; de Bortoli, N.; Marciano, E. Robotic Colonoscopy and Beyond: Insights into Modern Lower Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfredi, L. Endorobots for Colonoscopy: Design Challenges and Available Technologies. Front. Robot. AI 2021, 8, 705454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Borvorntanajanya, K.; Chen, K.; Franco, E.; y Baena, F.R. Design, control and evaluation of a novel soft everting robot for colonoscopy. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2025, 41, 4843–4859. [Google Scholar]

- Valdastri, P.; Webster, R.J.; Quaglia, C.; Quirini, M.; Menciassi, A.; Dario, P. A New Mechanism for Mesoscale Legged Locomotion in Compliant Tubular Environments. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2009, 25, 1047–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, S.; Metin, S. Design and Rolling Locomotion of a Magnetically Actuated Soft Capsule Endoscope. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2012, 28, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Veiga, T.; Chandler, J.H.; Lloyd, P.; Pittiglio, G.; Wilkinson, N.J.; Hoshiar, A.K.; Harris, R.A.; Valdastri, P. Challenges of continuum robots in clinical context: A review. Prog. Biomed. Eng. 2020, 2, 032003. [Google Scholar]

- Hoang, M.C.; Le, V.H.; Kim, J.; Choi, E.; Kang, B.; Kim, C.S.; Park, J.O. Development of an External Electromagnetic Actuation System to Enable Unrestrained Maneuverability for an Endoscopic Capsule. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Cyborg and Bionic Systems 2018, CBS 2018, Shenzhen, China, 25–27 October 2018; pp. 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chautems, C.; Tonazzini, A.; Boehler, Q.; Jeong, S.H.; Floreano, D.; Nelson, B.J. Magnetic Continuum Device with Variable Stiffness for Minimally Invasive Surgery. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2020, 2, 1900086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boini, A.; Acciuffi, S.; Croner, R.; Illanes, A.; Milone, L.; Turner, B.; Gumbs, A.A. Scoping review: Autonomous endoscopic navigation. Art. Int. Surg. 2023, 3, 233–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trovato, G.; Shikanai, M.; Ukawa, G.; Kinoshita, J.; Murai, N.; Lee, J.W.; Ishii, H.; Takanishi, A.; Tanoue, K.; Ieiri, S.; et al. Development of a colon endoscope robot that adjusts its locomotion through the use of reinforcement learning. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 2010, 5, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pore, A.; Finocchiaro, M.; Dallalba, D.; Hernansanz, A.; Ciuti, G.; Arezzo, A.; Menciassi, A.; Casals, A.; Fiorini, P. Colonoscopy Navigation using End-to-End Deep Visuomotor Control: A User Study. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Kyoto, Japan, 23–27 October 2022; pp. 9582–9588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsi, D.; Marzari, L.; Pore, A.; Farinelli, A.; Casals, A.; Fiorini, P.; Dall’Alba, D. Constrained Reinforcement Learning and Formal Verification for Safe Colonoscopy Navigation. arXiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Gupta, S. Controlled actuation, adhesion, and stifness in soft robots: A review. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2022, 106, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tziatzios, G.; Gkolfakis, P.; Lazaridis, L.D.; Facciorusso, A.; Antonelli, G.; Hassan, C.; Repici, A.; Sharma, P.; Rex, D.K.; Triantafyllou, K. High-definition colonoscopy for improving adenoma detection: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2020, 91, 1027–1036.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkinson, N.S.; Ket, S.; Bassett, P.; Aponte, D.; De Aguiar, S.; Gupta, N.; Horimatsu, T.; Ikematsu, H.; Inoue, T.; Kaltenbach, T.; et al. Narrow-band imaging for detection of neoplasia at colonoscopy: A meta-analysis of data from individual patients in randomized controlled trials. Gastroenterology 2019, 157, 462–471. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, K.M.; Mak, P.I.; Law, M.K.; Martins, R.P. CMOS biosensors for: In vitro diagnosis-transducing mechanisms and applications. Lab Chip 2016, 16, 3664–3681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teramoto, A.; Hamada, S.; Ogino, B.; Yasuda, I.; Sano, Y. Updates in narrow-band imaging for colorectal polyps: Narrow-band imaging generations, detection, diagnosis, and artificial intelligence. Dig. Endosc. 2023, 35, 453–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, M.W.; Buchner, A.M.; Heckman, M.G.; Krishna, M.; Raimondo, M.; Woodward, T.; Wallace, M.B. Diagnostic accuracy of probe-based confocal laser endomicroscopy and narrow band imaging for small colorectal polyps: A feasibility study. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2012, 107, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adler, D.C.; Zhou, C.; Tsai, T.-H.; Schmitt, J.; Huang, Q.; Mashimo, H.; Fujimoto, J.G. Three-dimensional endomicroscopy of the human colon using optical coherence tomography. Opt. Express 2009, 17, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Tian, C.X.; Mu, Y.; Ma, M.; Zhang, Z.; Wan, M.; Liu, J.; Li, Z.; Zuo, X.; Li, W.; et al. Hyperspectral imaging facilitating resect-and-discard strategy through artificial intelligence-assisted diagnosis of colorectal polyps: A pilot study. Cancer Med. 2024, 13, e70195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Yan, G.; Wang, Z.; He, S.; Xu, F.; Jiang, P.; Liu, D. Design and Testing of a Motor-Based Capsule Robot Powered by Wireless Power Transmission. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2016, 21, 683–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliparast, P. A new smart CMOS image sensor with on-chip neuro-fuzzy bleeding detection system for wireless capsule endoscopy. J. Med. Signals Sens. 2020, 10, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lallement, G.; Abouzeid, F.; Cochet, M.; Daveau, J.M.; Roche, P.; Autran, J.L. A 2.7 pJ/cycle 16 MHz, 0.7 μW Deep Sleep Power ARM Cortex-M0+ Core SoC in 28 nm FD-SOI. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 2018, 53, 2088–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, T.H.; Wahid, K.A. Low power and low complexity compressor for video capsule endoscopy. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2011, 21, 1534–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Yan, G. Design and implementation of a clamper-based and motor-driven capsule robot powered by wireless power transmission. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 138151–138161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNulty, D.; Hennessy, A.; Li, M.; Armstrong, E.; Ryan, K.M. A review of Li-ion batteries for autonomous mobile robots: Perspectives and outlook for the future. J. Power Sources 2022, 545, 231943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verstraten, T.; Hosen, M.S.; Berecibar, M.; Vanderborght, B. Selecting Suitable Battery Technologies for Untethered Robot. Energies 2023, 16, 4904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikołajczyk, T.; Mikołajewski, D.; Kłodowski, A.; Łukaszewicz, A.; Mikołajewska, E.; Paczkowski, T.; Macko, M.; Skornia, M. Energy Sources of Mobile Robot Power Systems: A Systematic Review and Comparison of Efficiency. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 7547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preetam, S.; Pritam, P.; Mishra, R.; Rustagi, S.; Lata, S.; Malik, S. Empowering tomorrow’s medicine: Energy-driven micro/nano-robots redefining biomedical applications. Mol. Syst. Des. Eng. 2024, 9, 892–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasouli, M.; Phee, L.S.J. Energy sources and their development for application in medical devices. Expert Rev. Med. Devices 2010, 7, 693–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bock, D.C.; Marschilok, A.C.; Takeuchi, K.J.; Takeuchi, E.S. Batteries used to Power Implantable Biomedical Devices. Electrochim. Acta 2012, 84, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayahpour, B.; Hirsh, H.; Bai, S.; Schorr, N.B.; Lambert, T.N.; Mayer, M.; Bao, W.; Cheng, D.; Zhang, M.; Leung, K.; et al. Revisiting Discharge Mechanism of CFx as a High Energy Density Cathode Material for Lithium Primary Battery. Adv. Energy Mater. 2022, 12, 2103196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Kang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, L.; Liu, J.; Li, Y.; Liang, Z.; He, X.; Li, X.; Tavajohi, N.; et al. A review of lithium-ion battery safety concerns: The issues, strategies, and testing standards. J. Energy Chem. 2021, 59, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazumder, A.N.; Meng, J.; Rashid, H.A.; Kallakuri, U.; Zhang, X.; Seo, J.S.; Mohsenin, T. A Survey on the Optimization of Neural Network Accelerators for Micro-AI On-Device Inference. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Circuits Syst. 2021, 11, 532–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaskas, K.; Karatzas, A.; Sad, C.; Siozios, K.; Anagnostopoulos, I.; Zervakis, G.; Henkel, J. Hardware-Aware DNN Compression via Diverse Pruning and Mixed-Precision Quantization. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Top. Comput. 2024, 12, 1079–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sander, J.; Cohen, A.; Dasari, V.R.; Venable, B.; Jalaian, B. On Accelerating Edge AI: Optimizing Resource-Constrained Environments. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.15014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vurukonda, N.; Burugari, V.K.; Jadala, V.C.; Reddy Beeram, S.; Gogula, M.R. Optimization of Lightweight AI Model for Low Power Predictive Analytics in Fog Edge Cintinuum. J. Inf. Syst. Eng. Manag. 2024, 9, 1753–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghani, A.; Aina, A.; Hwang See, C. An Optimised CNN Hardware Accelerator Applicable to IoT End Nodes for Disruptive Healthcare. IoT 2024, 5, 901–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavinkattimath, S.; Khanai, R.; Torse, D.; Iyer, N. Design and implementation of low-power, high-speed, reliable and secured Hardware Accelerator using 28 nm technology for biomedical devices. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2024, 88, 105554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahafi, A.; Wang, Y.; Rasmussen, C.L.M.; Bollen, P.; Baatrup, G.; Blanes-Vidal, V.; Herp, J.; Nadimi, E.S. Edge artificial intelligence wireless video capsule endoscopy. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 13723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, T. Optimization Strategies for Low-Power AI Models on Embedded Devices. Appl. Comput. Eng. 2025, 133, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, T.F.; Klinkao, J.; Urbina, S.; Pottackal, N.T.; Bell, M.D.; Rajappan, A.; Yavas, D.; Preston, D.J. Understanding silicone elastomer curing and adhesion for stronger soft devices. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, 2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Nakib, R.; Toncheva, A.; Fontaine, V.; Vanheuverzwijn, J.; Raquez, J.M.; Meyer, F. Thermoplastic polyurethanes for biomedical application: A synthetic, mechanical, antibacterial, and cytotoxic study. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2022, 139, 51666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palaniappan, K.; Lin, E.Y.T.; Vogel, S. Global Regulatory Frameworks for the Use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in the Healthcare Services Sector. Healthcare 2024, 12, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borys, K.; Schmitt, Y.A.; Nauta, M.; Seifert, C.; Krämer, N.; Friedrich, C.M.; Nensa, F. Explainable AI in medical imaging: An overview for clinical practitioners–Beyond saliency-based XAI approaches. Eur. J. Radiol. 2023, 162, 110786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Velden, B.H.M.; Kuijf, H.J.; Gilhuijs, K.G.A.; Viergever, M.A. Explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) in deep learning-based medical image analysis. Med. Image Anal. 2022, 79, 102470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, W.; Li, X.; Fatehi, M.; Hamarneh, G. Guidelines and evaluation of clinical explainable AI in medical image analysis. Med. Image Anal. 2023, 84, 102684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostermann, M.; Mathias, R.; Jahed, F.; Parker, M.B.; Hudson, F.D.; Harding, W.C.; Gilbert, S.; Freyer, O. Cybersecurity requirements for medical devices in the EU and US—A comparison and gap analysis of the MDCG 2019–16 and FDA premarket cybersecurity guidance. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2025, 28, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, W.J.; Ikoma, N.; Lyu, H.; Jackson, G.P.; Landman, A. Protecting procedural care-cybersecurity considerations for robotic surgery. NPJ Digit. Med. 2022, 5, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dora Stern, A.; Gordon, W.J.; Landman, A.B.; Kramer, D.B.; Smith, S.F. Cybersecurity features of digital medical devices: An analysis of FDA product summaries. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e025374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skytterholm, A.N.; Androutsos, C.; Ntanis, A.; Jaatun, M.G. Cybersecurity Guidances for Medical Devices: An MDCG and FDA Regulatory Comparison. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE International Conference on Smart Computing, SMARTCOMP, Cork, Ireland, 16–19 June 2025; pp. 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fosch-Villaronga, E.; Mahler, T. Cybersecurity, safety and robots: Strengthening the link between cybersecurity and safety in the context of care robots. Comput. Law Secur. Rev. 2021, 41, 105528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEC 81001-5-1:2021; Health Software and Health IT Systems Safety, Effectiveness and Security—Part 5-1: Security—Activities in the Product Life Cycle. International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC): Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- IEC 80001-1:2021; Application of Risk Management for IT-Networks Incorporating Medical Devices—Part 1: Safety, Effectiveness and Security in the Implementation and Use of Connected Medical Devices or Connected Health Software. International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC): Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- Freyer, O.; Jahed, F.; Ostermann, M.; Rosenzweig, C.; Werner, P.; Gilbert, S. Consideration of Cybersecurity Risks in the Benefit-Risk Analysis of Medical Devices: Scoping Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2024, 26, e65528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Locomotion Type | Principle | Advantages | Limitations | Translational Implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peristaltic (biomimetic) | Segmental contraction inspired by earthworm locomotion. | Smooth, tissue-conforming motion; low trauma. | Complex actuation; slow speed; miniaturization challenge. | Promising for atraumatic navigation, but power and complexity limit scalability. |

| Ambulatory (legged) | Walking using mechanical legs or arms. | High adaptability to terrain; precise positioning. | Mechanically complex; risk of mucosal trauma. | Useful for precision tasks but clinically limited by safety concerns. |

| Rolling/Wheeling | Continuous rotation of wheels or treads. | Fast locomotion; stable on straight segments. | Poor performance in sharp bends; potential abrasion of mucosa. | Simple and efficient but best suited for short or straight colonic paths. |

| Magnetic (external actuation) | Movement via external magnetic fields. | Wireless control; avoids onboard propulsion systems. | Control precision limited; performance affected by anatomy variability. | Clinically feasible with external magnet systems; already tested in capsule endoscopy. |

| Immobile (passive) | Propelled externally (manual push or magnetic drag). | Low onboard complexity; passive imaging/diagnostics possible. | No active control; limited maneuverability in complex anatomy. | Suitable for capsule diagnostics but not for therapeutic interventions. |

| Technology | Clinical Utility | Translational Implications | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| CMOS sensors | Enable detection of biological markers (e.g., proteins, cells) relevant to polyp characterization and differentiation. | Foundation for compact, high-resolution endorobotic platforms; allows integration of AI-based tissue classification. | [77] |

| Narrow Band Imaging (NBI) | Enhances specificity in identifying dysplastic lesions and adenomas. | Already incorporated into commercial endoscopy; provides benchmark for validating AI-based optical biopsy. | [78] |

| Confocal Laser Endomicroscopy (CLE) | Provides “optical biopsy” with high sensitivity for lesions <5 mm; distinguishes neoplastic from non-neoplastic tissue. | High diagnostic accuracy but limited adoption due to cost and complexity; potential role in targeted robotic platforms. | [79] |

| Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) | Detects submucosal invasion; enables monitoring of healing and tissue microstructure. | Adds depth resolution; integration into endorobotics could support minimally invasive staging. | [80] |

| Hyperspectral/Multispectral Imaging | Identifies molecular signatures; differentiates hyperplastic from dysplastic lesions. | Promising research tool for AI-driven molecular endoscopy; limited by data processing and hardware miniaturization. | [81] |

| Component | Estimated Power Consumption | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| DC micromotors (inchworm locomotion) | Up to 2 W | [82] |

| HD CMOS Image Sensor | ~0.5 W | [83] |

| ARM Cortex Microcontroller | ~0.3 W | [84] |

| Wireless Transmission (Wi-Fi/Bluetooth) | ~0.5 W | [85] |

| Real-time Video Streaming | 1–2 W | [86] |

| Battery Type | Key Characteristics | |

|---|---|---|

| Lithium Iodide (Li/I2) | Common in medical implants due to long life, low self-discharge, and chemical stability. Used in pacemakers and neurostimulators. | [92] |

| Lithium Carbon Monofluoride (Li/CFx) | High energy density (~560–720 Wh/kg), long shelf-life, non-leaking, suitable for capsule endoscopy; downside: low rate capability and heat during discharge | [93] |

| Lithium Polymer (LiPo) | High energy-to-weight ratio (~300 Wh/kg), rechargeable, but has safety concerns (thermal runaway, swelling); less favorable for in vivo use | [94] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Al Zaabi, A.; Al Maashri, A.; Bourdoucen, H.; A. Al-Busafi, S. Emerging Endorobotic and AI Technologies in Colorectal Cancer Screening: A Review of Design, Validation, and Translational Pathways. Diagnostics 2026, 16, 421. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16030421

Al Zaabi A, Al Maashri A, Bourdoucen H, A. Al-Busafi S. Emerging Endorobotic and AI Technologies in Colorectal Cancer Screening: A Review of Design, Validation, and Translational Pathways. Diagnostics. 2026; 16(3):421. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16030421

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl Zaabi, Adhari, Ahmed Al Maashri, Hadj Bourdoucen, and Said A. Al-Busafi. 2026. "Emerging Endorobotic and AI Technologies in Colorectal Cancer Screening: A Review of Design, Validation, and Translational Pathways" Diagnostics 16, no. 3: 421. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16030421

APA StyleAl Zaabi, A., Al Maashri, A., Bourdoucen, H., & A. Al-Busafi, S. (2026). Emerging Endorobotic and AI Technologies in Colorectal Cancer Screening: A Review of Design, Validation, and Translational Pathways. Diagnostics, 16(3), 421. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16030421