Efficacy of Combined Cervical Pessary and Progesterone in Women at High-Risk of Preterm Birth †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Population Selection and Characterization for the Post Hoc Analysis

Analytical Strategy and Study Populations

- •

- Intervention Group: Received a combination of a cervical pessary plus vaginal progesterone.

- •

- Control Group: Received vaginal progesterone alone

2.3. Primary and Secondary Outcomes

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.4.1. Sample Description

2.4.2. Group Comparisons

2.4.3. Multivariate Analysis

2.4.4. Diagnostic Accuracy Analysis

2.4.5. Survival Analysis

2.4.6. Sample Size and Statistical Power

2.4.7. Statistical Software

2.4.8. Specific Methodological Aspects of Post Hoc Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Basic Demographic Characteristics

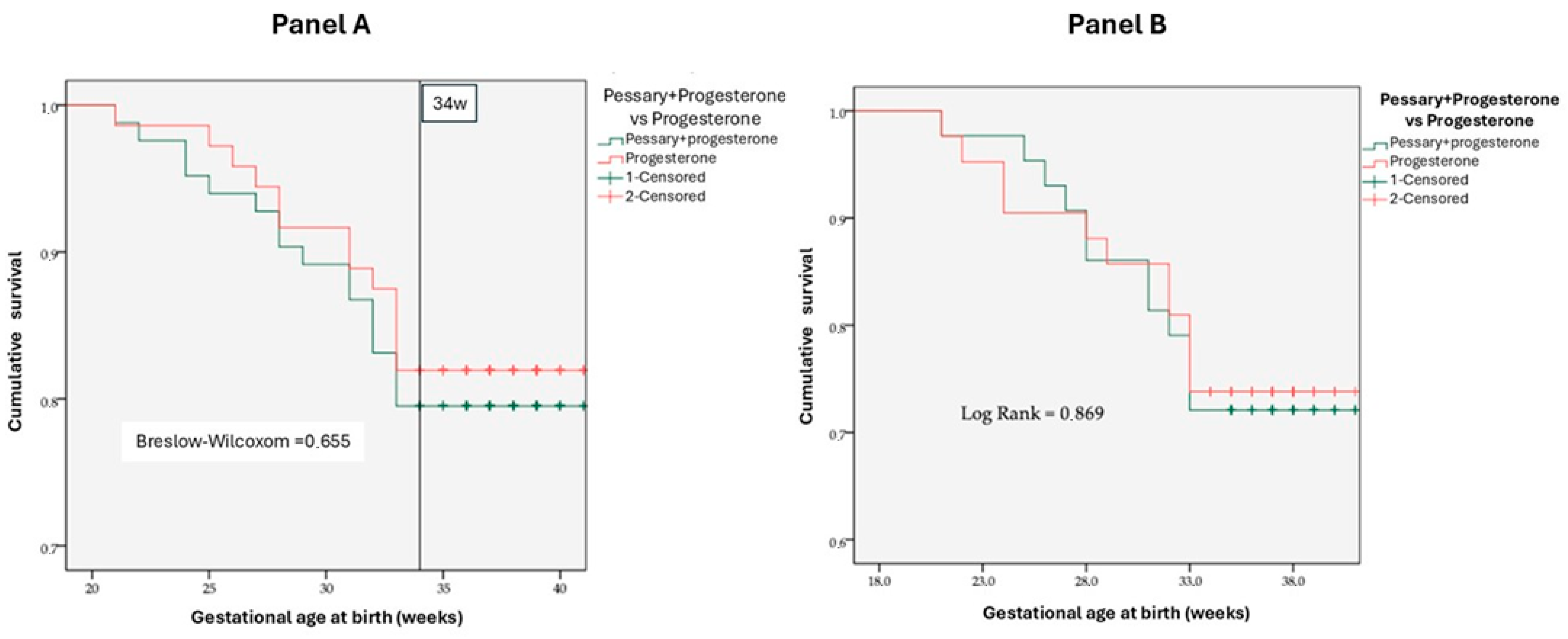

3.2. Cervical Pessary Efficacy

3.3. Predictive Factors for Recurrent Preterm Birth

4. Discussion

4.1. Synthesis of Main Findings

4.2. Re-Evaluating Mechanistic Hypotheses for Pessary Non-Efficacy in Recurrent Preterm Birth

4.3. Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Recurrent Cervical Insufficiency

4.4. The “Missed Therapeutic Window” Paradigm

4.5. International Comparisons and Population Heterogeneity

4.6. Implications of Ethnic Diversity in Brazil

4.7. Implications for Predictive Modeling and Personalized Care

4.8. Limitations and Methodological Perspectives

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chawanpaiboon, S.; Vogel, J.P.; Moller, A.B.; Lumbiganon, P.; Petzold, M.; Hogan, D.; Landoulsi, S.; Jampathong, N.; Kongwattanakul, K.; Laopaiboon, M.; et al. Global, regional, and national estimates of levels of preterm birth in 2014: A systematic review and modelling analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2019, 7, e37–e46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Oza, S.; Hogan, D.; Perin, J.; Rudan, I.; Lawn, J.E.; Cousens, S.; Mathers, C.; Black, R.E. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality in 2000–13, with projections to inform post-2015 priorities: An updated systematic analysis. Lancet 2015, 385, 430–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Medicine (US). Committee on Understanding Premature Birth and Assuring Healthy Outcomes. In Preterm Birth: Causes, Consequences, and Prevention; Behrman, R.E., Butler, A.S., Eds.; National Academies Press (US): Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Do Carmo Leal, M.; Esteves-Pereira, A.P.; Nakamura-Pereira, M.; Torres, J.A.; Theme-Filha, M.; Domingues, R.M.S.M.; Dias, M.A.B.; Moreira, M.E.; Gama, S.G. Prevalence and risk factors related to preterm birth in Brazil. Reprod. Health 2016, 13, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercer, B.M.; Goldenberg, R.L.; Moawad, A.H.; Meis, P.J.; Ianis, J.D.; Das, A.F.; Caritis, S.N.; Miodovnik, M.; Menard, M.; Thurnau, G.R.; et al. The Preterm Prediction Study: Effect of gestational age and cause of preterm birth on subsequent obstetric outcome. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1999, 181, 1216–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esplin, M.S.; O’Brien, E.; Fraser, A.; Kerber, R.A.; Clark, E.; Simonsen, S.E.; Holmgren, C.; Mineau, G.P.; Varner, M.W. Estimating Recurrence of Spontaneous Preterm Delivery. Obstet. Gynecol. 2008, 112, 516–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iams, J.D.; Goldenberg, R.L.; Meis, P.J.; Mercer, B.M.; Moawad, A.; Das, A.; Thom, E.; McNellis, D.; Copper, R.L.; Johnson, F.; et al. The length of the cervix and the risk of spontaneous premature delivery. New Engl. J. Med. 1996, 334, 567–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero, R.; Dey, S.K.; Fisher, S.J. Preterm labor: One syndrome, many causes. Science 2014, 345, 760–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Word, R.A.; Li, X.H.; Hnat, M.; Carrick, K. Dynamics of cervical remodeling during pregnancy and parturition: Mechanisms and current concepts. Semin. Reprod. Med. 2007, 25, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myers, K.M.; Feltovich, H.; Mazza, E.; Vink, J.; Bajka, M.; Wapner, R.J.; Hall, T.J.; House, M. The mechanical role of the cervix in pregnancy. J. Biomech. 2015, 48, 1511–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, E.B.; Celik, E.; Parra, M.; Singh, M.; Nicolaides, K.H. Fetal Medicine Foundation Second Trimester Screening Group. Progesterone and the Risk of Preterm Birth among Women with a Short Cervix. New Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 462–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.S.; Romero, R.; Vidyadhari, D.; Fusey, S.; Baxter, J.K.; Khandelwal, M.; Vijayaraghavan, J.; Trivedi, Y.; Soma-Pillay, P.; Sambarey, P.; et al. Vaginal progesterone reduces the rate of preterm birth in women with a sonographic short cervix: A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2011, 38, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, R.; Nicolaides, K.; Conde-Agudelo, A.; Tabor, A.; O’Brien, J.M.; Cetingoz, E.; Da Fonseca, E.; Creasy, G.W.; Klein, K.; Rode, L.; et al. Vaginal progesterone in women with an asymptomatic sonographic short cervix in the midtrimester decreases preterm delivery and neonatal morbidity: A systematic review and metaanalysis of individual patient data. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012, 206, 124.e1–124.e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, R.; Conde-Agudelo, A.; Nicolaides, K.H. Vaginal progesterone for preventing preterm birth and adverse perinatal outcomes in singleton gestations with a short cervix: Meta-analysis of individual patient data. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017, 218, 161–180. [Google Scholar]

- Norman, J.E.; Marlow, N.; McConnachie, A.; Petrou, S.; Sebire, N.J.; Lavender, T.; Whyte, S.; Norrie, J.; Messow, C.-M.; Shennan, A.; et al. Vaginal progesterone prophylaxis for preterm birth (the OPPTIMUM study): A multicentre, randomised, double-blind trial. Lancet 2016, 387, 2106–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conde-Agudelo, A.; Romero, R.; Da Fonseca, E.; O’Brien, J.M.; Cetingoz, E.; Creasy, G.W.; Hassan, S.S.; Erez, O.; Pacora, P.; Nicolaides, K.H. Vaginal progesterone is as effective as cervical cerclage to prevent preterm birth in women with a singleton gestation, previous spontaneous preterm birth, and a short cervix: Updated indirect comparison meta-analysis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 219, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, J.; Hankins, G.; Iams, J.D.; Berghella, V.; Sheffield, J.S.; Perez-Delboy, A.; Egerman, R.S.; Wing, D.A.; Tomlinson, M.; Silver, R.; et al. Multicenter randomized trial of cerclage for preterm birth prevention in high-risk women with shortened midtrimester cervical length. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2009, 201, 375.e1–375.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berghella, V.; Odibo, A.O.; To, M.S.; Rust, O.A.; Althuisius, S.M. Cerclage for Short Cervix on Ultrasonography Meta-Analysis of Trials Using Individual Patient-Level Data. Obstet. Gynecol. 2005, 106, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Aleem, H.; Shaaban, O.M.; Abdel-Aleem, M.A.; Aboelfadle Mohamed, A. Cervical pessary for preventing preterm birth in singleton pregnancies. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2022, 12, CD014508. [Google Scholar]

- Goya, M.; Pratcorona, L.; Merced, C.; Rodó, C.; Valle, L.; Romero, A.; Juan, M.; Rodríguez, A.; Muñoz, B.; Santacruz, B.; et al. Cervical pessary in pregnant women with a short cervix (PECEP): An open-label randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2012, 379, 1800–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfirevic, Z.; Stampalija, T.; Medley, N. Cervical stitch (cerclage) for preventing preterm birth in singleton pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 6, CD008991. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Saccone, G.; Maruotti, G.M.; Giudicepietro, A.; Martinelli, P.; Italian Preterm Birth Prevention (IPP) Working Group. Effect of cervical pessary on spontaneous preterm birth in women with singleton pregnancies and short cervical length a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2017, 318, 2317–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfirevic, Z.; Owen, J.; Carreras Moratonas, E.; Sharp, A.N.; Szychowski, J.M.; Goya, M. Vaginal progesterone, cerclage or cervical pessary for preventing preterm birth in asymptomatic singleton pregnant women with a history of preterm birth and a sonographic short cervix. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2013, 41, 146–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacagnella, R.C.; Silva, T.V.; Cecatti, J.G.; Passini, R.; Fanton, T.F.; Borovac-Pinheiro, A.; Pereira, C.M.; Fernandes, K.G.; França, M.S.; Li, W. Pessary Plus Progesterone to Prevent Preterm Birth in Women With Short Cervixes: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 139, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berghella, V.; Gulersen, M.; Roman, A.; Boelig, R.C. Vaginal progesterone for the prevention of recurrent spontaneous preterm birth. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM 2023, 5, 101116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koullali, B.; Oudijk, M.A.; Nijman, T.A.J.; Mol, B.W.J.; Pajkrt, E. Risk assessment and management to prevent preterm birth. Semin. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016, 21, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacagnella, R.C.; Mol, B.W.; Borovac-Pinheiro, A.; Passini, R., Jr.; Nomura, M.L.; Andrade, K.C.; Ellovitch, N.; Fernandes, K.G.; Bortoletto, T.G.; Pereira, C.M.; et al. A randomized controlled trial on the use of pessary plus progesterone to prevent preterm birth in women with short cervical length (P5 trial). BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019, 19, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goya, M.; Pratcorona, L.; Higueras, T.; Perez-Hoyos, S.; Carreras, E.; Cabero, L. Sonographic cervical length measurement in pregnant women with a cervical pessary. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2011, 38, 205–209. [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza Cobaleda, M.; Ribera, I.; Maiz, N.; Goya, M.; Carreras, E. Cervical modifications after pessary placement in singleton pregnancies with maternal short cervical length: 2D and 3D ultrasound evaluation. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2019, 98, 1442–1449. [Google Scholar]

- Timmons, B.; Akins, M.; Mahendroo, M. Cervical remodeling during pregnancy and parturition. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 21, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatanaka, A.R.; Mattar, R.; Kawanami, T.E.; França, M.S.; Rolo, L.C.; Nomura, R.M.; Júnior, E.A.; Nardozza, L.M.M.; Moron, A.F. Amniotic fluid “sludge” is an independent risk factor for preterm delivery. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016, 29, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatanaka, A.R.; Franca, M.S.; Hamamoto, T.E.N.K.; Rolo, L.C.; Mattar, R.; Moron, A.F. Antibiotic treatment for patients with amniotic fluid “sludge” to prevent spontaneous preterm birth: A historically controlled observational study. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2019, 98, 1157–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, M.; Bhadelia, R.A.; Myers, K.; Socrate, S. Magnetic resonance imaging of three-dimensional cervical anatomy in the second and third trimester. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2009, 144, S65–S69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannie, M.M.; Dobrescu, O.; Gucciardo, L.; Strizek, B.; Ziane, S.; Sakkas, E.; Schoonjans, F.; Divano, L.; Jani, J.C. Arabin cervical pessary in women at high risk of preterm birth: A magnetic resonance imaging observational follow-up study. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2013, 42, 426–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldjian, C.; Adam, R.; Pelosi, M.; Pelosi, M. MRI Appearance of cervical incompetence in a pregnant patient. Magn. Reson. Imaging 1999, 17, 1399–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toprak, E.; Bozkurt, M.; Çakmak, B.D.; Özçimen, E.E.; Silahlı, M.; Yumru, A.E.; Çalışkan, E. Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio: A new inflammatory marker for the diagnosis of preterm premature rupture of membranes. J. Turk. Ger. Gynecol. Assoc. 2017, 18, 122–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, K.J.; Romero, R.; Park, J.Y.; Lee, J.; Conde-Agudelo, A.; Hong, J.S.; Yoon, B.H. Evidence that antibiotic administration is effective in the treatment of a subset of patients with intra-amniotic infection/ inflammation presenting with cervical insufficiency. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 221, 140.e1–140.e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Chen, Q.; Wang, Y. Correlation of amniotic fluid inflammatory markers with preterm birth: A meta-analysis. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2024, 44, 2368764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coutinho, C.M.; Sotiriadis, A.; Odibo, A.; Khalil, A.; D’Antonio, F.; Feltovich, H.; Salomon, L.J.; Sheehan, P.; Napolitano, R.; Berghella, V. ISUOG Practice Guidelines: Role of ultrasound in the prediction of spontaneous preterm birth. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 60, 435–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarde, A.; Lutsiv, O.; Beyene, J.; McDonald, S.D. Vaginal progesterone, oral progesterone, 17-OHPC, cerclage, and pessary for preventing preterm birth in at-risk singleton pregnancies: An updated systematic review and network meta-analysis. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2019, 126, 556–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simanek, A.M.; Xiong, M.; Woo, J.M.P.; Zheng, C.; Zhang, Y.S.; Meier, H.C.S.; Aiello, A.E. Association between prenatal socioeconomic disadvantage, adverse birth outcomes, and inflammatory response at birth. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2023, 153, 106090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panceri, C.; Valentini, N.C.; Silveira, R.C.; Smith, B.A.; Procianoy, R.S. Neonatal Adverse Outcomes, Neonatal Birth Risks, and Socioeconomic Status: Combined Influence on Preterm Infants’ Cognitive, Language, and Motor Development in Brazil. J. Child. Neurol. 2020, 35, 989–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Andrade, L.; Kozhumam, A.S.; Rocha, T.A.H.; de Almeida, D.G.; da Silva, N.C.; de Souza Queiroz, R.C.; Massago, M.; Rent, S.; Facchini, L.A.; da Silva, A.A.M. Impact of socioeconomic factors and health determinants on preterm birth in Brazil: A register-based study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leal, M.D.C.; Esteves-Pereira, A.P.; Nakamura-Pereira, M.; Torres, J.A.; Domingues, R.M.S.M.; Dias, M.A.B.; Moreira, M.E.; Theme-Filha, M.; da Gama, S.G.N. Provider-initiated late preterm births in Brazil: Differences between public and private health services. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0155511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diniz, C.S.G.; De Miranda, M.J.; Reis-Queiroz, J.; Queiroz, M.R.; De Oliveira Salgado, H. Why do women in the private sector have shorter pregnancies in Brazil? Left shift of gestational age, caesarean section and inversion of the expected disparity. J. Human. Growth Dev. 2016, 26, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berghella, V.; Owen, J.; MacPherson, C.; Yost, N.; Swain, M.; Dildy, G.A.; Miodovnik, M.; Langer, O.; Sibai, B. Natural history of cervical funneling in women at high risk for spontaneous preterm birth. Obstet. Gynecol. 2007, 109, 863–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creswell, L.; Rolnik, D.L.; Lindow, S.W.; O’Gorman, N. Preterm Birth: Screening and Prediction. Int. J. Womens Health 2023, 15, 1981–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anum, E.A.; Springel, E.H.; Shriver, M.D.; Strauss, J.F. Genetic Contributions to Disparities in Preterm Birth. Pediatr. Res. 2009, 65, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Outcome | Progesterone Alone [% (n)] (n = 72) | Pessary + Progesterone [% (n)] (n = 83) | OR (CI 95%) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <28 weeks | 5.6 (4) | 7.2 (6) | 1.325 (0.359–4.892) | 0.672 |

| <32 weeks | 11.1 (8) | 13.3 (11) | 1.222 (0.463–3.227) | 0.685 |

| <34 weeks | 18.1 (13) | 20.5 (17) | 1.169 (0.524–2.609) | 0.703 |

| <37 weeks | 40.3 (29) | 39.8 (33) | 0.979 (0.514–1.864) | 0.948 |

| Outcome | Progesterone Alone [% (n)] (n = 43) | Pessary + Progesterone [% (n)] (n = 42) | OR (CI 95%) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <28 weeks | 9.3 (4) | 9.5 (4) | 1.500 (0.392–5.733) | 0.551 |

| <32 weeks | 18.6 (8) | 14.3 (6) | 0.946 (0.320–2.795) | 0.920 |

| <34 weeks | 27.9 (12) | 26.2 (11) | 1.167 (0.466–2.921) | 0.742 |

| <37 weeks | 46.5 (20) | 45.2 (19) | 1.100 (0.476–2.541) | 0.823 |

| Predictor | OR | CI 95% | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Higher education | 2.37 | 0.99–5.63 | 0.024 |

| Previous conization | 4.78 | 1.08–21.19 | 0.039 |

| Previous low birth weight | 2.43 | 1.22–4.85 | 0.051 |

| Previous miscarriages | 1.36 | 1.10–1.69 | 0.005 |

| Twin pregnancy | 14.86 | 4.35–50.68 | <0.001 |

| Cervical funneling | 3.6 | 1.79–7.24 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

França, M.S.; França, G.U.S.; Hatanaka, A.R.; Traina, E.; Hamamoto, T.E.K.; Silva, D.B.; Araujo Júnior, E.; Mattar, R.; Braga, A.; Pacagnella, R.d.C. Efficacy of Combined Cervical Pessary and Progesterone in Women at High-Risk of Preterm Birth. Diagnostics 2026, 16, 402. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16030402

França MS, França GUS, Hatanaka AR, Traina E, Hamamoto TEK, Silva DB, Araujo Júnior E, Mattar R, Braga A, Pacagnella RdC. Efficacy of Combined Cervical Pessary and Progesterone in Women at High-Risk of Preterm Birth. Diagnostics. 2026; 16(3):402. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16030402

Chicago/Turabian StyleFrança, Marcelo Santucci, Gabriela Ubeda Santucci França, Alan Roberto Hatanaka, Evelyn Traina, Tatiana Emy Kawanami Hamamoto, Danilo Brito Silva, Edward Araujo Júnior, Rosiane Mattar, Antonio Braga, and Rodolfo de Carvalho Pacagnella. 2026. "Efficacy of Combined Cervical Pessary and Progesterone in Women at High-Risk of Preterm Birth" Diagnostics 16, no. 3: 402. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16030402

APA StyleFrança, M. S., França, G. U. S., Hatanaka, A. R., Traina, E., Hamamoto, T. E. K., Silva, D. B., Araujo Júnior, E., Mattar, R., Braga, A., & Pacagnella, R. d. C. (2026). Efficacy of Combined Cervical Pessary and Progesterone in Women at High-Risk of Preterm Birth. Diagnostics, 16(3), 402. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16030402