The Use of Digital Neurocognitive Assessments to Assess Traumatic Brain Injury and Dementia in Older Trauma Patients: An Emergency Department Feasibility Study †

Abstract

1. Introduction

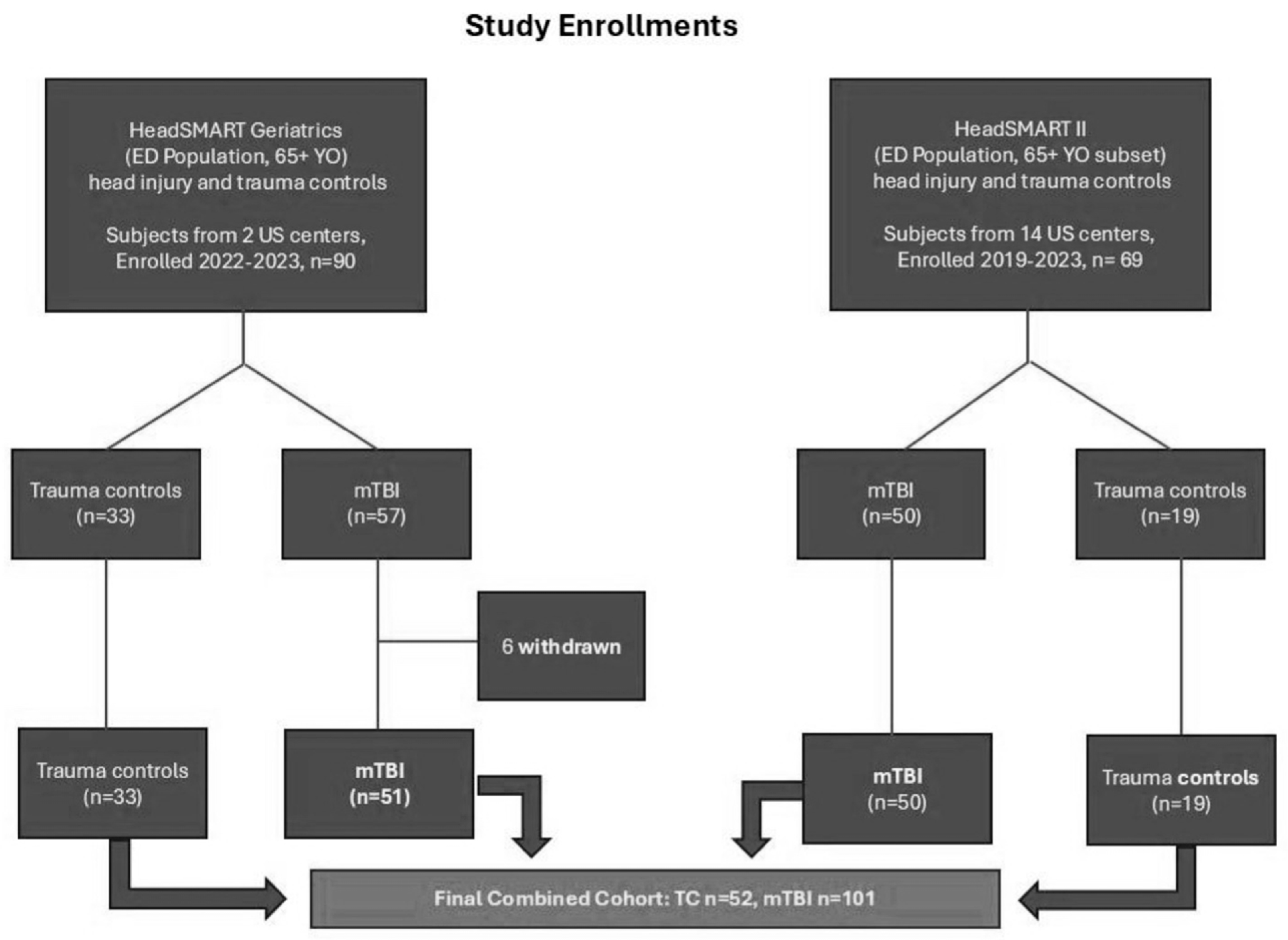

2. Methods

2.1. Neurocognitive Testing Procedures

2.2. BrainCheck Digital Neurocognitive Assessment

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characterization

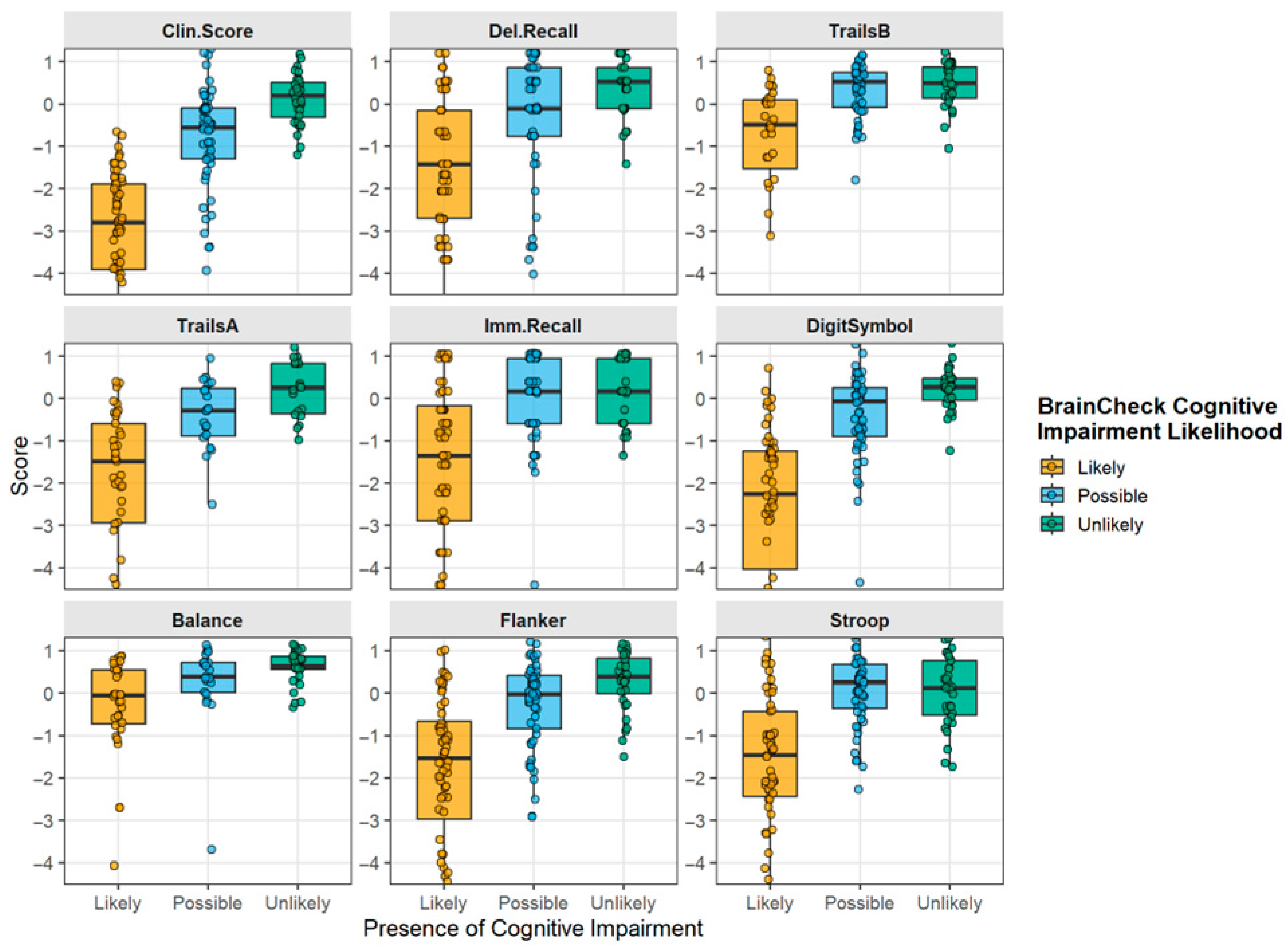

3.2. Digital Neurocognitive Assessments for TBI in Geriatric Trauma Patients

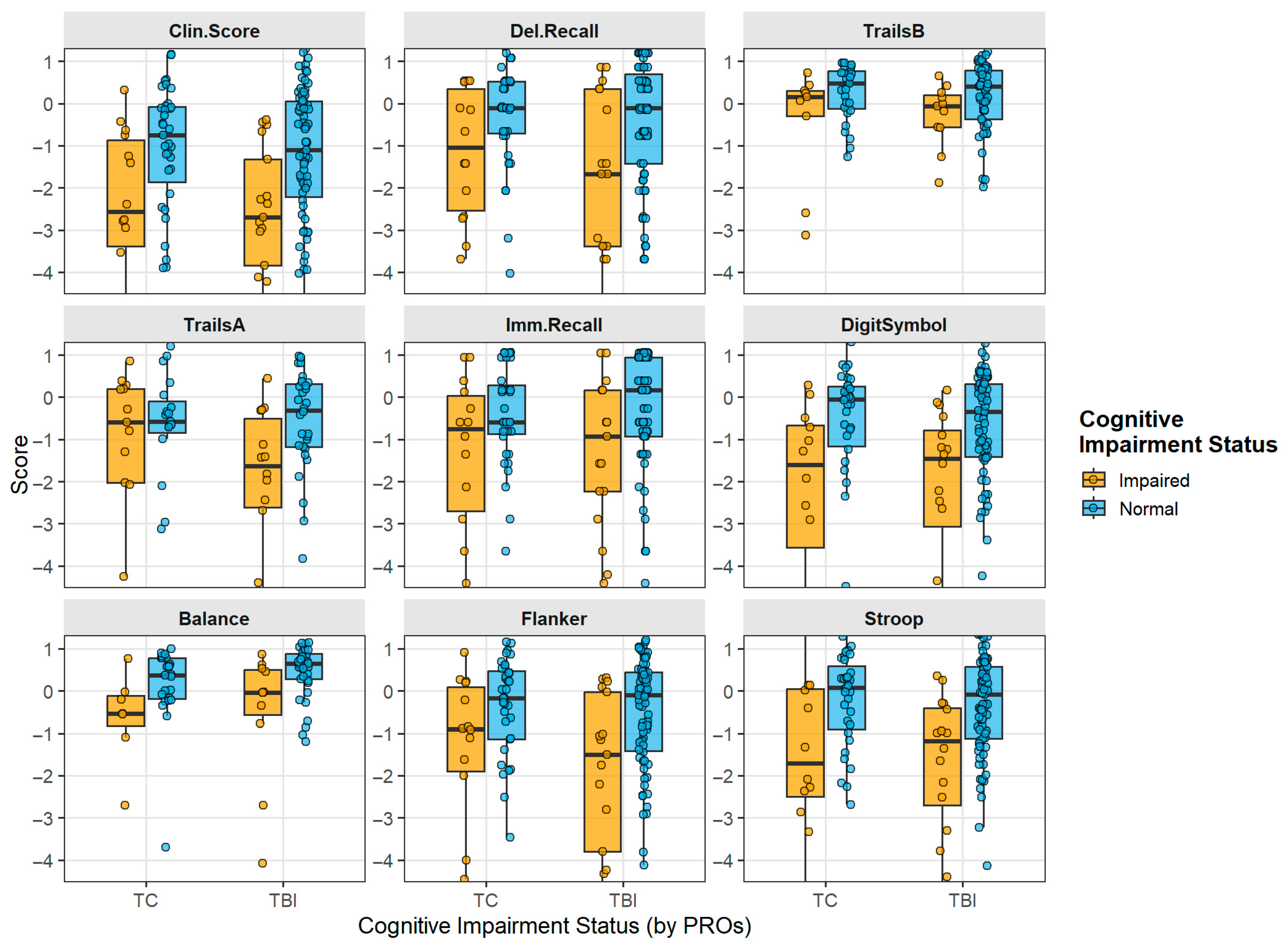

3.3. Effect of Preinjury Impairment on Individual Neurocognitive Tests

3.4. Technology Familiarity as a Factor Affecting Tablet-Based Neurocognitive Testing

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Waltzman, D.; Haarbauer-Krupa, J.; Womack, L.S. Traumatic Brain Injury in Older Adults-A Public Health Perspective. JAMA Neurol. 2022, 79, 437–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairns, C.; Ashman, J.J.; Kang, K. Emergency Department Visit Rates by Selected Characteristics: United States, 2022; National Center for Health Statistics: Hyattsville, MD, USA, 2024; NCHS Data Brief 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.E.; Gardner, R.C. Traumatic brain injury in older adults: Do we need a different approach? Concussion 2018, 3, CNC56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, R.C.; Dams-O’Connor, K.; Morrissey, M.R.; Manley, G.T. Geriatric Traumatic Brain Injury: Epidemiology, Outcomes, Knowledge Gaps, and Future Directions. J. Neurotrauma 2018, 35, 889–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; He, Z.; Li, Z.; Gong, R.; Hui, J.; Weng, W.; Wu, X.; Yang, C.; Jiang, J.; Xie, L.; et al. Traumatic brain injury in elderly population: A global systematic review and meta-analysis of in-hospital mortality and risk factors among 2.22 million individuals. Ageing Res. Rev. 2024, 99, 102376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennon, M.J.; Brooker, H.; Creese, B.; Thayanandan, T.; Rigney, G.; Aarsland, D.; Hampshire, A.; Ballard, C.; Corbett, A.; Raymont, V. Lifetime Traumatic Brain Injury and Cognitive Domain Deficits in Late Life: The PROTECT-TBI Cohort Study. J. Neurotrauma 2023, 40, 1423–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savioli, G.; Ceresa, I.F.; Ciceri, L.; Sciutti, F.; Belliato, M.; Iotti, G.A.; Luzzi, S.; Del Maestro, M.; Mezzini, G.; Lafe, E.; et al. Mild head trauma in elderly patients: Experience of an emergency department. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreland, B.; Kakara, R.; Henry, A. Trends in Nonfatal Falls and Fall-Related Injuries Among Adults Aged ≥65 Years—United States, 2012–2018. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 875–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, D.E.; Byers, A.L.; Gardner, R.C.; Seal, K.H.; Boscardin, W.J.; Yaffe, K. Association of Mild Traumatic Brain Injury With and Without Loss of Consciousness With Dementia in US Military Veterans. JAMA Neurol. 2018, 75, 1055–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, V.; Bath, J.; Harvey, E.; Martinez, M.; Weppner, J. Factors impacting mortality and withdrawal of life sustaining therapy in severe traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 2025, 39, 689–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fann, J.R.; Ribe, A.R.; Pedersen, H.S.; Fenger-Grøn, M.; Christensen, J.; Benros, M.E.; Vestergaard, M. Long-term risk of dementia among people with traumatic brain injury in Denmark: A population-based observational cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry 2018, 5, 424–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dams-O’Connor, K.; Gibbons, L.E.; Bowen, J.D.; McCurry, S.M.; Larson, E.B.; Crane, P.K. Risk for late-life re-injury, dementia and death among individuals with traumatic brain injury: A population-based study. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2012, 84, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, D.E.; Kaup, A.; Kirby, K.A.; Byers, A.L.; Diaz-Arrastia, R.; Yaffe, K. Traumatic brain injury and risk of dementia in older veterans. Neurology 2014, 83, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, A.L.C.; Selvin, E.; Latour, L.; Turtzo, L.C.; Coresh, J.; Mosley, T.; Ling, G.; Gottesman, R.F. Head injury and 25-year risk of dementia. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2021, 17, 1432–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, R.C.; Bahorik, A.; Kornblith, E.S.; Allen, I.E.; Plassman, B.L.; Yaffe, K. Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and Population Attributable Risk of Dementia Associated with Traumatic Brain Injury in Civilians and Veterans. J. Neurotrauma 2023, 40, 620–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingston, G.; Huntley, J.; Sommerlad, A.; Ames, D.; Ballard, C.; Banerjee, S.; Brayne, C.; Burns, A.; Cohen-Mansfield, J.; Cooper, C.; et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet 2020, 396, 413–446, Corrected in Lancet 2023, 402, 1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, N.S.; Sharp, D.J. Understanding neurodegeneration after traumatic brain injury: From mechanisms to clinical trials in dementia. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2019, 90, 1221–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, L.M.; Ballard, C.G.; Rowan, E.N.; Kenny, R.A. Incidence and prediction of falls in dementia: A prospective study in older people. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e5521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero-Odasso, M.; van der Velde, N.; Martin, F.C.; Petrovic, M.; Tan, M.P.; Ryg, J.; Aguilar-Navarro, S.; Alexander, N.B.; Becker, C.; Blain, H.; et al. World guidelines for falls prevention and management for older adults: A global initiative. Age Ageing 2022, 51, afac205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muir, S.W.; Gopaul, K.; Odasso, M.M.M. The role of cognitive impairment in fall risk among older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing 2012, 41, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordoobadi, A.J.; Dhanani, H.; Tulebaev, S.R.; Salim, A.; Cooper, Z.; Jarman, M.P. Risk of Dementia Diagnosis After Injurious Falls in Older Adults. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2436606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dams-O’Connor, K.; Juengst, S.B.; Bogner, J.; Chiaravalloti, N.D.; Corrigan, J.D.; Giacino, J.T.; Harrison-Felix, C.L.; Hoffman, J.M.; Ketchum, J.M.; Lequerica, A.H.; et al. Traumatic brain injury as a chronic disease: Insights from the United States Traumatic Brain Injury Model Systems Research Program. Lancet Neurol. 2023, 22, 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.K.; Hou, S.W.; Lee, C.C.; Hsu, C.Y.; Huang, Y.S.; Su, Y.C. Increased risk of dementia in patients with mild traumatic brain injury: A nationwide cohort study. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e62422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, A.L.C.; Huie, J.R.; Boscardin, W.J.; Nelson, L.; Barber, J.K.; Yaffe, K.; Diaz-Arrastia, R.; Ferguson, A.R.; Kramer, J.; Jain, S.; et al. Cognitive Outcome 1 Year After Mild Traumatic Brain Injury: Results From the TRACK-TBI Study. Neurology 2022, 98, e1248–e1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brett, B.L.; Temkin, N.; Barber, J.K.; Okonkwo, D.O.; Stein, M.; Bodien, Y.G.; Corrigan, J.; Diaz-Arrastia, R.; Giacino, J.T.; McCrea, M.A.; et al. Long-term Multidomain Patterns of Change After Traumatic Brain Injury: A TRACK-TBI LONG Study. Neurology 2023, 101, e740–e753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacono, D.; Raiciulescu, S.; Olsen, C.; Perl, D.P. Traumatic Brain Injury Exposure Lowers Age of Cognitive Decline in AD and Non-AD Conditions. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 573401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, R.C.; Burke, J.F.; Nettiksimmons, J.; Kaup, A.; Barnes, D.E.; Yaffe, K. Dementia risk after traumatic brain injury vs nonbrain trauma: The role of age and severity. JAMA Neurol. 2014, 71, 1490–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groppell, S.; Soto-Ruiz, K.M.; Flores, B.; Dawkins, W.; Smith, I.; Eagleman, D.M.; Katz, Y. A Rapid, Mobile Neurocognitive Screening Test to Aid in Identifying Cognitive Impairment and Dementia (BrainCheck): Cohort Study. MIR Aging 2019, 2, e12615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peacock, W.F.; Kuehl, D.; Bazarian, J.; Singer, A.J.; Cannon, C.; Rafique, Z.; D’ETienne, J.P.; Welch, R.; Clark, C.; Diaz-Arrastia, R. Defining Acute Traumatic Encephalopathy: Methods of the “HEAD Injury Serum Markers and Multi-Modalities for Assessing Response to Trauma” (HeadSMART II) Study. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 733712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S.; Sun, K.; Huynh, D.; Phi, H.Q.; Ko, B.; Huang, B.; Ghomi, R.H. A Computerized Cognitive Test Battery for Detection of Dementia and Mild Cognitive Impairment: Instrument Validation Study. JMIR Aging 2022, 5, e36825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aramvanitch, K. Age-appropriateness of decision for brain CT scan in elderly patients with mild traumatic brain injury. World J. Emerg. Med. 2023, 14, 227–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, N.; Gariepy, C.; Prévost, J.F.; Belhumeur, V.; Fortier, É.; Carmichael, P.H.; Gariepy, J.-L.; Le Sage, N.; Émond, M. Adapting the Canadian CT head rule age criteria for mild traumatic brain injury. Emerg. Med. J. 2019, 36, 617–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiell, I.G.; Wells, G.A.; Vandemheen, K.; Clement, C.; Lesiuk, H.; Laupacis, A.; McKnight, R.D.; Verbeek, R.; Brison, R.; Cass, D.; et al. The Canadian CT Head Rule for patients with minor head injury. Lancet 2001, 357, 1391–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haydel, M.J.; Preston, C.A.; Mills, T.J.; Luber, S.; Blaudeau, E.; DeBlieux, P.M. Indications for computed tomography in patients with minor head injury. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000, 343, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Flores, B.; Magal, R.; Harris, K.; Gross, J.; Ewbank, A.; Davenport, S.; Ormachea, P.; Nasser, W.; Le, W.; et al. Diagnostic accuracy of tablet-based software for the detection of concussion. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0179352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofman, P.; Stapert, S.; Kroonenburgh Mvan Jolles, J.; Kruijk Jde Wilmink, J. MR imaging, single-photon emission CT, and neurocognitive performance after mild traumatic brain injury. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2001, 3, 441–449. [Google Scholar]

- Lezak, M. Neuropsychological Assessment, 5th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cubillos, C.; Rienzo, A. Digital Cognitive Assessment Tests for Older Adults: Systematic Literature Review. JMIR Ment. Health 2023, 10, e47487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazarian, J.J.; Biberthaler, P.; Welch, R.D.; Lewis, L.M.; Barzo, P.; Bogner-Flatz, V.; Brolinson, P.G.; Büki, A.; Chen, J.Y.; Christenson, R.H.; et al. Serum GFAP and UCH-L1 for prediction of absence of intracranial injuries on head CT (ALERT-TBI): A multicentre observational study. Lancet Neurol. 2018, 17, 782–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, M.J.; Korley, F.K. Head Computed Tomography Use in the Emergency Department for Mild Traumatic Brain Injury: Integrating Evidence Into Practice for the Resident Physician. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2012, 60, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazeli, P.L.; Ross, L.A.; Vance, D.E.; Ball, K. The relationship between computer experience and computerized cognitive test performance among older adults. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2012, 68, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverberg, N.D.; Iverson, G.L.; Cogan, A.; Dams-O-Connor, K.; Delmonico, R.; Graf, M.J.P.; Iaccarino, M.A.; Kajankova, M.; Kamins, J.; McCulloch, K.L.; et al. The American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine Diagnostic Criteria for Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2023, 104, 1343–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.C.; Tseng, Y.M.; Chen, Y.C.; Chen, P.Y.; Chiu, H.Y. Diagnostic accuracy of the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale for detecting mild cognitive impairment and dementia: A bivariate meta-analysis. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2020, 36, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webber, D.; Collins, M.; DeFilippis, N.; Hill, F. Reliability of the Clinical Dementia Rating with a traumatic brain injury population: A preliminary study. Appl Neuropsychol Adult 2013, 20(2), 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, D.A.; Gonzales, M.M.; Resch, Z.J.; Sullivan, A.C.; Soble, J.R. Comprehensive Evaluation of the Functional Activities Questionnaire (FAQ) and Its Reliability and Validity. Assessment 2021, 29, 748–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaronson, A.; Diaz, A.; Ashford, M.T.; Jin, C.; Tank, R.; Miller, M.J.; Kang, J.M.; Manjavong, M.; Landavazo, B.; Eichenbaum, J.; et al. Self- and Informant-Report Cognitive Decline Discordance and Mild Cognitive Impairment Diagnosis. JAMA Netw. Open 2025, 8, e255810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu-Seifert, H.; Siemers, E.; Price, K.; Han, B.; Selzler, K.J.; Henley, D.; Sundell, K.; Aisen, P.; Cummings, J.; Raskin, J.; et al. Cognitive Impairment Precedes and Predicts Functional Impairment in Mild Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2015, 47, 205–214. [Google Scholar]

- Temkin, N.; Machamer, J.; Dikmen, S.; Nelson, L.D.; Barber, J.; Hwang, P.H.; Boase, K.; Stein, M.B.; Sun, X.; Giacino, J.; et al. Risk Factors for High Symptom Burden Three Months after Traumatic Brain Injury and Implications for Clinical Trial Design: A Transforming Research and Clinical Knowledge in Traumatic Brain Injury Study. J. Neurotrauma 2022, 39, 1524–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, K.J.L.; Sullivan, K.A. Factor structure of the modified Rivermead Post-concussion Symptoms Questionnaire (mRPQ): An exploratory analysis with healthy adult simulators. Brain Inj. 2023, 37, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, K.J.L.; Sullivan, K.A. Validating the modified Rivermead Post-concussion Symptoms Questionnaire (mRPQ). Clin. Neuropsychol. 2021, 37, 207–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czaja, S.J.; Sharit, J. Age Differences in Attitudes Toward Computers. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 1998, 53B, P329–P340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iverson, G.L.; Brooks, B.L.; Ashton, V.L.; Johnson, L.G.; Gualtieri, C.T. Does familiarity with computers affect computerized neuropsychological test performance? J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 2009, 31, 594–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanlon, L.; O’Shea, E.; O’Caoimh, R.; Timmons, S. Usability and Validity of a Battery of Computerised Cognitive Screening Tests for Detecting Cognitive Impairment. Gerontology 2015, 62, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, M.I.; Shih, L.C.; Kolachalama, V.B. Machine Learning in Clinical Trials: A Primer with Applications to Neurology. Neurotherapeutics 2023, 20, 1066–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kolluri, S.; Lin, J.; Liu, R.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, W. Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence in Pharmaceutical Research and Development: A Review. AAPS J. 2022, 24, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Marques, L.; Costa, B.; Pereira, M.; Silva, A.; Santos, J.; Saldanha, L.; Silva, I.; Magalhães, P.; Schmidt, S.; Vale, N. Advancing Precision Medicine: A Review of Innovative In Silico Approaches for Drug Development, Clinical Pharmacology and Personalized Healthcare. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Weppner, J.L.; Gray, J.; Sandsmark, D.; Mirshahi, N.; Diaz-Arrastia, R.; Rascovsky, K.; Huang, B.; Huynh, D.; Van Meter, T. Differentiating Traumatic Brain Injury from Dementia in Older Adults Using BrainCheck: An Emergency Medicine Feasibility Study. Presented at 42nd Annual National Neurotrauma Society Symposium, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 15–18 June 2025. [Google Scholar]

| TC | TBI | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 52) | (n = 101) | ||

| Age | 70.0 (65.8–75.0) | 73.0 (68.0–78.0) | 0.041 |

| Sex | 0.24 | ||

| Female | 24 (46.2%) | 57 (56.4%) | |

| Male | 28 (53.8%) | 44 (43.6%) | |

| Race | 0.26 | ||

| White | 37 (71.2%) | 81 (80.2%) | |

| African American/Black | 15 (28.8%) | 17 (16.8%) | |

| Asian | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.0%) | |

| Not Reported | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (2.0%) | |

| Education | 0.92 | ||

| Less than a high school education | 3 (5.8%) | 8 (7.9%) | |

| High school degree or equivalent (e.g., GED) | 11 (21.2%) | 23 (22.8%) | |

| Some college | 28 (53.8%) | 54 (53.4%) | |

| Graduate or professional degree | 8 (15.3%) | 15 (14.9%) | |

| Missing | 2 (3.8%) | 1 (1.0%) | |

| Vital signs and clinical measures | |||

| Heart rate (beats per minute) at intake | 0.35 | ||

| Median (IQR) | 77.0 (72.0–86.5) | 76.0 (68.0–84.0) | |

| Missing | 1 (1.9%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Systolic BP (mmHg.) at intake | 0.55 | ||

| Median (IQR) | 152.0 (141.0–168.5) | 150.0 (133.0–167.0) | |

| Missing | 1 (1.9%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg.) at intake | 0.65 | ||

| Median (IQR) | 79.0 (71.0–86.5) | 78.0 (71.0–84.0) | |

| Missing | 1 (1.9%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Body Mass Index at intake | 26.0 (22.5–30.6) | 27.3 (23.9–30.8) | 0.38 |

| ED Evaluation time from injury (h) | 4.1 (1.7–22.6) | 1.8 (1.0–6.3) | 0.005 |

| BC Duration (min) | 0.68 | ||

| Median (IQR) | 16.0 (13.0–19.0) | 15.0 (13.0–19.5) | |

| Missing | 2 (3.8%) | 2 (2.0%) | |

| Mode of arrival | 0.28 | ||

| Ambulance | 23 (44.2%) | 55 (54.5%) | |

| Friend/family member | 9 (17.3%) | 21 (20.8%) | |

| Self-transport | 8 (15.4%) | 12 (11.9%) | |

| Transfer from other facility | 12 (23.1%) | 12 (11.9%) | |

| Missing | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.0%) | |

| Mechanism of injury | 0.01 | ||

| Fall from standing | 32 (61.5%) | 77 (76.2%) | |

| Motor Vehicle Collision (not ejected) | 6 (11.5%) | 7 (6.9%) | |

| Head struck by/against object | 0 (0.0%) | 7 (6.9%) | |

| Pedestrian struck by vehicle | 1 (1.9%) | 2 (2.0%) | |

| Pedal Cycle (non-motorized with helmet) | 1 (1.9%) | 1 (1.0%) | |

| Other | 12 (23%) | 6 (6%) | |

| Missing | 1 (1.9%) | 1 (1.0%) |

| TBI-Related Injury Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| TBI | |

| (n = 101) | |

| Type of injury | |

| Blunt Head Trauma | 53 (52.5%) |

| Blunt Head Trauma with Additional Trauma Injury | 48 (47.5%) |

| Head Neuroimaging results (CT/MRI) | |

| Negative | 79 (78.2%) |

| Positive | 18 (17.8%) |

| No CT | 4 (4.0%) |

| GCS | |

| 14 | 4 (4.0%) |

| 15 | 97 (96.0%) |

| ACRM | |

| ACRM− | 24 (23.8%) |

| ACRM+ | 77 (76.2%) |

| Headache at intake | |

| Yes | 68 (67.3%) |

| No | 33 (32.7%) |

| Not applicable | 0 (0.0%) |

| Severe headache | |

| Yes | 26 (25.7%) |

| No | 41 (40.6%) |

| Not applicable | 0 (0.0%) |

| Unknown | 14 (13.9%) |

| Missing | 20 (19.8%) |

| Loss of consciousness | |

| Yes | 45 (44.6%) |

| Not Sure | 9 (8.9%) |

| No | 47 (46.5%) |

| Not applicable | 0 (0.0%) |

| Post-traumatic amnesia (PTA) | |

| Yes | 22 (21.8%) |

| Not Sure | 1 (1.0%) |

| No | 78 (77.2%) |

| Not applicable | 0 (0.0%) |

| PTA (Affecting memories before injury) | |

| Yes | 14 (13.9%) |

| No | 8 (7.9%) |

| Not applicable | 79 (78.2%) |

| PTA (Affecting memories after injury) | |

| Yes | 17 (16.8%) |

| No | 5 (5.0%) |

| Not applicable | 79 (78.2%) |

| Disorientation/Confusion | |

| Yes | 39 (38.6%) |

| Not Sure | 2 (2.0%) |

| No | 60 (59.4%) |

| Not applicable | 0 (0.0%) |

| Focal neurological deficit | |

| Yes | 32 (31.7%) |

| Not Sure | 3 (3.0%) |

| No | 66 (65.3%) |

| Not applicable | 0 (0.0%) |

| Post-traumatic seizure | |

| Yes | 0 (0.0%) |

| Not Sure | 2 (2.0%) |

| No | 99 (98.0%) |

| Not applicable | 0 (0.0%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Weppner, J.; Gray, J.; Kuehl, D.; Sandsmark, D.; Mirshahi, N.; Diaz-Arrastia, R.; Rascovsky, K.; Peacock, W.F.; Van Meter, T.E. The Use of Digital Neurocognitive Assessments to Assess Traumatic Brain Injury and Dementia in Older Trauma Patients: An Emergency Department Feasibility Study. Diagnostics 2026, 16, 400. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16030400

Weppner J, Gray J, Kuehl D, Sandsmark D, Mirshahi N, Diaz-Arrastia R, Rascovsky K, Peacock WF, Van Meter TE. The Use of Digital Neurocognitive Assessments to Assess Traumatic Brain Injury and Dementia in Older Trauma Patients: An Emergency Department Feasibility Study. Diagnostics. 2026; 16(3):400. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16030400

Chicago/Turabian StyleWeppner, Justin, Justin Gray, Damon Kuehl, Danielle Sandsmark, Nazanin Mirshahi, Ramon Diaz-Arrastia, Katya Rascovsky, W. Frank Peacock, and Timothy E. Van Meter. 2026. "The Use of Digital Neurocognitive Assessments to Assess Traumatic Brain Injury and Dementia in Older Trauma Patients: An Emergency Department Feasibility Study" Diagnostics 16, no. 3: 400. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16030400

APA StyleWeppner, J., Gray, J., Kuehl, D., Sandsmark, D., Mirshahi, N., Diaz-Arrastia, R., Rascovsky, K., Peacock, W. F., & Van Meter, T. E. (2026). The Use of Digital Neurocognitive Assessments to Assess Traumatic Brain Injury and Dementia in Older Trauma Patients: An Emergency Department Feasibility Study. Diagnostics, 16(3), 400. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16030400