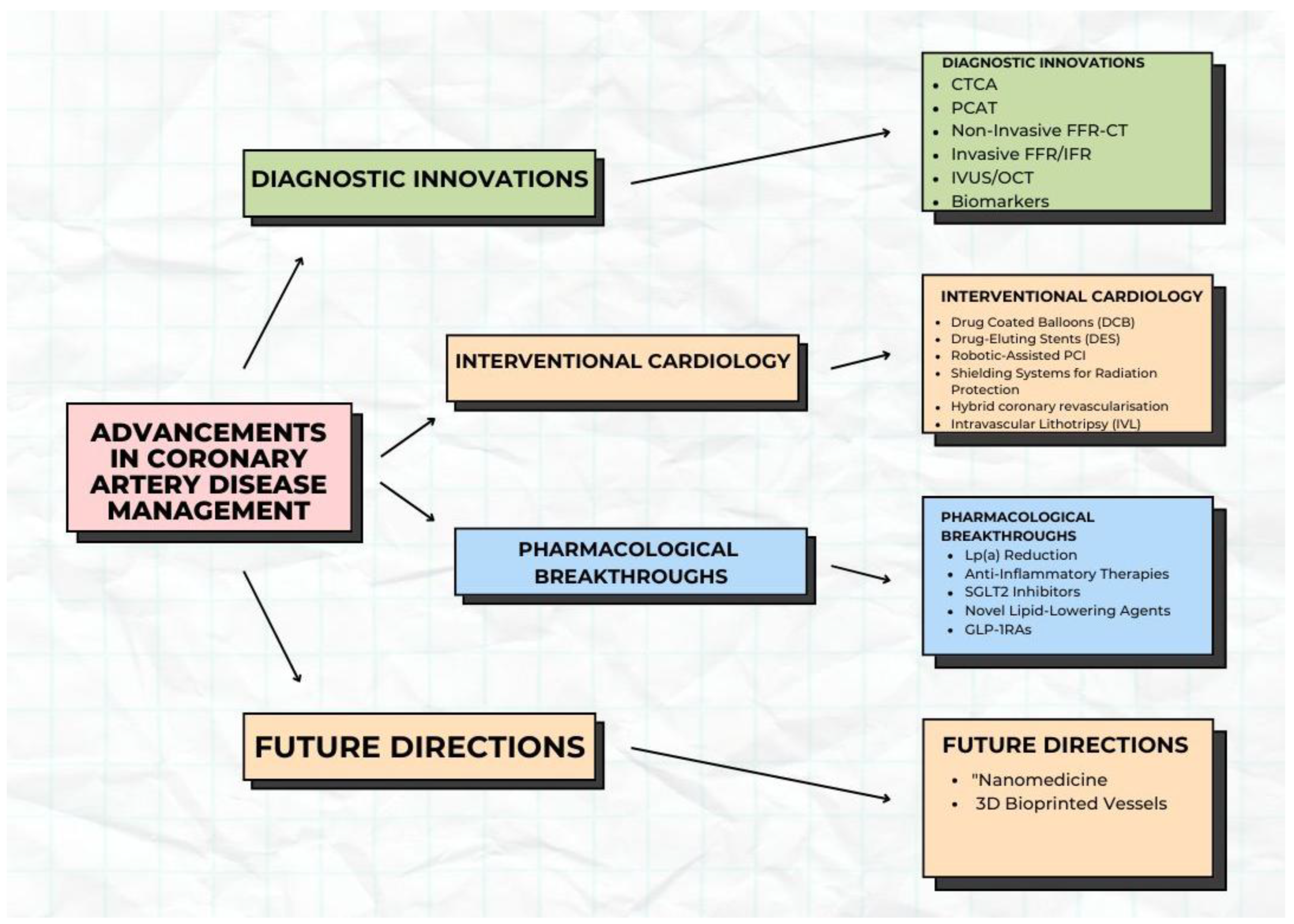

Innovations in Diagnosis and Treatment of Coronary Artery Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Diagnostic Innovations

3.1. Advanced Imaging Techniques

3.1.1. High-Resolution CT Angiography for Early Plaque Detection

3.1.2. Pericoronary Adipose Tissue (PCAT)

3.1.3. Non-Invasive Fractional Flow Reserve (FFR-CT) to Assess Blood Flow

3.1.4. Invasive Functional Assessment of Epicardial Stenosis Severity

3.1.5. Intravascular Imaging in the Detection of Vulnerable Plaque

3.2. Biomarkers

3.2.1. High-Sensitivity Troponin Assays for Early Detection of Myocardial Injury

3.2.2. Interleukin-6 (IL-6)

3.2.3. Lipoprotein [Lp(a)]

3.2.4. High-Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein

4. Advances in Interventional Cardiology for Coronary Artery Disease

4.1. Drug-Coated Balloons in CAD Management

4.1.1. DCBs for ISR

4.1.2. DCB in Denovo Lesion

4.1.3. Future of DCBs

4.2. Drug-Eluting Stents in CAD Management

4.2.1. Historical Context

4.2.2. Modern Innovations

Thinner Strut Designs

Biodegradable Polymers

Polymer-Free Stents

Advanced Drugs

4.2.3. Clinical Benefits

4.2.4. Challenges

4.3. Robotic-Assisted Percutaneous Coronary Intervention

4.3.1. Key Features

Precision and Stability

Radiation Protection

Remote Operation (Tele-Stenting)

4.3.2. Clinical and Operator Benefits

4.3.3. Safety in Complex Lesions

Challenges

4.4. Shielding Systems for Radiation Protection

4.5. Hybrid Coronary Revascularisation

4.6. Intravascular Lithotripsy (IVL)

5. Pharmacological Breakthroughs

5.1. Lipoprotein(a) Reduction

5.2. Anti-Inflammatory Therapies

5.2.1. Monoclonal Antibodies

5.2.2. Colchicine

5.2.3. Methotrexate

5.3. Sodium–Glucose Cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) Inhibitors

5.4. New, Novel Lipid-Lowering Agents for Reducing Cardiovascular Risk

5.5. Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists (GLP-1RAs)

6. Future Directions and Challenges

6.1. Advancements in Nanomedicine

6.2. 3D-Printed Artificial Blood Vessels

6.3. Clinical Implications and Future Directions

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| AMI | Acute Myocardial Infarction |

| BMS | Bare-Metal Stent |

| BVS | Bioresorbable Vascular Scaffold |

| CABG | Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting |

| CAD | Coronary Artery Disease |

| CTCA | Computerised tomography Coronary Angiography |

| CFD | Computational Fluid Dynamics |

| CRP | C-Reactive Protein |

| DCB | Drug-Coated Stent |

| DES | Drug-Eluting Stent |

| ECG | Electrocardiogram |

| FFR-CT | Fractional Flow Reserve derived from CT |

| GLP-1RAs | Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists |

| hs-cTn | High-Sensitivity Cardiac Troponin |

| ICA | Invasive Coronary Angiography |

| ISR | In-Stent Restenosis |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1 Beta |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| IVL | Intravascular Lithotripsy |

| IVUS | Intravascular Ultrasound |

| LDL | Low-Density Lipoprotein |

| Lp(a) | Lipoprotein(a) |

| NSTEMI | Non-ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction |

| OCT | Optical Coherence Tomography |

| PCAT | Pericoronary Adipose Tissue |

| PCI | Percutaneous Coronary Intervention |

| PCSK9 | Protein Convertase Subtilisin/Kexin Type 9 |

| R-PCI | Robotic-Assisted Percutaneous Coronary Intervention |

| SGLT2 | Sodium–Glucose Cotransporter 2 |

References

- Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risks 2023 Collaborators. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risk Factors in 204 Countries and Territories, 1990–2023. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2025, 86, 2167–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, A.; Argulian, E.; Leipsic, J.; Newby, D.E.; Narula, J. From Subclinical Atherosclerosis to Plaque Progression and Acute Coronary Events: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 74, 1608–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowbar, A.N.; Rajkumar, C.; Al-Lamee, R.K.; Francis, D.P. Controversies in revascularisation for stable coronary artery disease. Clin. Med. 2021, 21, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraro, R.; Latina, J.M.; Alfaddagh, A.; Michos, E.D.; Blaha, M.J.; Jones, S.R.; Sharma, G.; Trost, J.C.; Boden, W.E.; Weintraub, W.S.; et al. Evaluation and Management of Patients With Stable Angina: Beyond the Ischemia Paradigm: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 76, 2252–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maron, D.J.; Hochman, J.S.; Reynolds, H.R.; Bangalore, S.; O’Brien, S.M.; Boden, W.E.; Chaitman, B.R.; Senior, R.; López-Sendón, J.; Alexander, K.P.; et al. Initial Invasive or Conservative Strategy for Stable Coronary Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1395–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Lamee, R.; Thompson, D.; Dehbi, H.-M.; Sen, S.; Tang, K.; Davies, J.; Keeble, T.; Mielewczik, M.; Kaprielian, R.; Malik, I.S.; et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention in stable angina (ORBITA): A double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2018, 391, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bruyne, B.; Pijls, N.H.; Kalesan, B.; Barbato, E.; Tonino, P.A.; Piroth, Z.; Jagic, N.; Mobius-Winckler, S.; Rioufol, G.; Witt, N.; et al. Fractional Flow Reserve–Guided PCI versus Medical Therapy in Stable Coronary Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 367, 991–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkumar, C.A.; Foley, M.J.; Ahmed-Jushuf, F.; Nowbar, A.N.; Simader, F.A.; Davies, J.R.; O’kAne, P.D.; Haworth, P.; Routledge, H.; Kotecha, T.; et al. A Placebo-Controlled Trial of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for Stable Angina. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 2319–2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SENIOR-RITA Trial Investigates the Use of an Invasive Strategy to Treat Older Patients After a NSTEMI. Available online: https://www.escardio.org/The-ESC/Press-Office/Press-releases/SENIOR-RITA-trial-investigates-the-use-of-an-invasive-strategy-to-treat-older-patients-after-a-NSTEMI (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- NICE. Cardiovascular Disease: Risk Assessment and Reduction, Including Lipid Modification; NICE: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ference, B.A.; Ginsberg, H.N.; Graham, I.; Ray, K.K.; Packard, C.J.; Bruckert, E.; Hegele, R.A.; Krauss, R.M.; Raal, F.J.; Schunkert, H.; et al. Low-density lipoproteins cause atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. 1. Evidence from genetic, epidemiologic, and clinical studies. A consensus statement from the European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel. Eur. Heart J. 2017, 38, 2459–2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mézquita, A.J.V.; Biavati, F.; Falk, V.; Alkadhi, H.; Hajhosseiny, R.; Maurovich-Horvat, P.; Manka, R.; Kozerke, S.; Stuber, M.; Derlin, T.; et al. Clinical quantitative coronary artery stenosis and coronary atherosclerosis imaging: A Consensus Statement from the Quantitative Cardiovascular Imaging Study Group. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2023, 20, 696–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Föllmer, B.; Williams, M.C.; Dey, D.; Arbab-Zadeh, A.; Maurovich-Horvat, P.; Volleberg, R.H.J.A.; Rueckert, D.; Schnabel, J.A.; Newby, D.E.; Dweck, M.R.; et al. Roadmap on the use of artificial intelligence for imaging of vulnerable atherosclerotic plaque in coronary arteries. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2024, 21, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Herten, R.L.M.; Lagogiannis, I.; Leiner, T.; Išgum, I. The role of artificial intelligence in coronary CT angiography. Neth. Heart J. 2024, 32, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uchida, Y.; Uchida, Y.; Shimoyama, E.; Hiruta, N.; Kishimoto, T.; Watanabe, S. Human pericoronary adipose tissue as storage and possible supply site for oxidized low-density lipoprotein and high-density lipoprotein in coronary artery. J. Cardiol. 2017, 69, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Z.; Liu, W.; Cao, D.; Tong, Q. Evaluating the role of pericoronary adipose tissue on coronary artery disease: Insights from CCTA on risk assessment, vascular stenosis, and plaque characteristics. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2024, 11, 1451807. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Yang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Xian, H.; Weng, Z.; Ji, L.; Yang, F. Non-invasive imaging innovation: FFR-CT combined with plaque characterization, safeguarding your cardiac health. J. Cardiovasc. Comput. Tomogr. 2024, 19, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottardi, A.; Prado, G.F.A.; Lunardi, M.; Fezzi, S.; Pesarini, G.; Tavella, D.; Scarsini, R.; Ribichini, F. Clinical Updates in Coronary Artery Disease: A Comprehensive Review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nørgaard, B.L.; Sand, N.P.; Jensen, J.M. Is CT-derived fractional flow reserve superior to ischemia testing? Expert. Rev. Cardiovasc. Ther. 2022, 20, 165–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Shan, D.; Wang, X.; Sun, X.; Shao, M.; Wang, K.; Pan, Y.; Wang, Z.; Schoepf, U.J.; Savage, R.H.; et al. On-Site Computed Tomography-Derived Fractional Flow Reserve to Guide Management of Patients with Stable Coronary Artery Disease: The TARGET Randomized Trial. Circulation 2023, 147, 1369–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, P.S.; De Bruyne, B.; Pontone, G.; Patel, M.R.; Norgaard, B.L.; Byrne, R.A.; Curzen, N.; Purcell, I.; Gutberlet, M.; Rioufol, G.; et al. 1-Year Outcomes of FFRCT-Guided Care in Patients With Suspected Coronary Disease: The PLATFORM Study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2016, 68, 435–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrodicasa, D.; Albrecht, M.H.; Schoepf, U.J.; Varga-Szemes, A.; Jacobs, B.E.; Gassenmaier, S.; De Santis, D.; Eid, M.H.; van Assen, M.; Tesche, C.; et al. Artificial intelligence machine learning-based coronary CT fractional flow reserve (CT-FFRML): Impact of iterative and filtered back projection reconstruction techniques. J. Cardiovasc. Comput. Tomogr. 2019, 13, 331–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrints, C.; Andreotti, F.; Koskinas, K.C.; Rossello, X.; Adamo, M.; Ainslie, J.; Banning, A.P.; Budaj, A.; Buechel, R.R.; Chiariello, G.A. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the Management of Chronic Coronary Syndromes: Developed by the task force for the management of chronic coronary syndromes of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) endorsed by the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, 3515–3537. [Google Scholar]

- Van Belle, E.; Rioufol, G.; Pouillot, C.; Cuisset, T.; Bougrini, K.; Teiger, E.; Champagne, S.; Belle, L.; Barreau, D.; Hanssen, M.; et al. Outcome impact of coronary revascularization strategy reclassification with fractional flow reserve at time of diagnostic angiography: Insights from a large french multicenter fractional flow reserve registry. Circulation 2014, 129, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curzen, N.; Rana, O.; Nicholas, Z.; Golledge, P.; Zaman, A.; Oldroyd, K.; Hanratty, C.; Banning, A.; Wheatcroft, S.; Hobson, A.; et al. Does routine pressure wire assessment influence management strategy at coronary angiography for diagnosis of chest pain? the ripcord study. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2014, 7, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Götberg, M.; Christiansen, E.H.; Gudmundsdottir, I.J.; Sandhall, L.; Danielewicz, M.; Jakobsen, L.; Olsson, S.-E.; Öhagen, P.; Olsson, H.; Omerovic, E.; et al. Instantaneous Wave-free Ratio versus Fractional Flow Reserve to Guide PCI. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 1813–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, J.E.; Sen, S.; Dehbi, H.-M.; Al-Lamee, R.; Petraco, R.; Nijjer, S.S.; Bhindi, R.; Lehman, S.J.; Walters, D.; Sapontis, J.; et al. Use of the Instantaneous Wave-free Ratio or Fractional Flow Reserve in PCI. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 1824–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.; Han, W.; Wang, S.; Jia, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Chen, B. Advantages of hybrid intravascular ultrasound-optical coherence tomography system in clinical practice. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2025, 12, 1595889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Zhou, Q. High-Resolution Intravascular Ultrasound: Advances in Coronary Plaque Characterization. Curr. Treat. Options Cardiovasc. Med. 2025, 27, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Veelen, A.; van der Sangen, N.M.R.; Delewi, R.; Beijk, M.A.M.; Henriques, J.P.S.; Claessen, B.E.P.M. Detection of Vulnerable Coronary Plaques Using Invasive and Non-Invasive Imaging Modalities. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bode, M.F.; Jaffer, F.A. IVUS and OCT: Current State-of-the-Art in Intravascular Coronary Imaging. Curr. Cardiovasc. Imaging Rep. 2019, 12, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roleder, T.; Kovacic, J.C.; Ali, Z.; Sharma, R.; Cristea, E.; Moreno, P.; Sharma, S.K.; Narula, J.; Kini, A.S. Combined NIRS and IVUS imaging detects vulnerable plaque using a single catheter system: A head-to-head comparison with OCT. EuroIntervention 2014, 10, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westwood, M.E.; Armstrong, N.; Worthy, G.; Fayter, D.; Ramaekers, B.L.T.; Grimm, S.; Buksnys, T.; Ross, J.; Mills, N.L.; Body, R.; et al. Optimizing the Use of High-Sensitivity Troponin Assays for the Early Rule-out of Myocardial Infarction in Patients Presenting with Chest Pain: A Systematic Review. Clin. Chem. 2021, 67, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmakis, D.; Mueller, C.; Apple, F.S. High-sensitivity cardiac troponin assays for cardiovascular risk stratification in the general population. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 4050–4056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, N.N.; deGoma, E.; Shapiro, M.D. IL-6 and Cardiovascular Risk: A Narrative Review. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2024, 27, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzidi, N.; Gamra, H. Relationship between serum interleukin-6 levels and severity of coronary artery disease undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2023, 23, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Hao, W.; Guo, Y.; Guo, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, X.; Nie, S. The association of lipoprotein (a) with coronary artery calcification: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Atherosclerosis 2024, 388, 117405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Y.H.; Lee, B.K.; Kwon, H.M.; Min, P.K.; Choi, E.Y.; Yoon, Y.W.; Hong, B.K.; Rim, S.J.; Kim, J.Y. Coronary calcification is associated with elevated serum lipoprotein (a) levels in asymptomatic men over the age of 45 years: A cross-sectional study of the Korean national health checkup data. Medicine 2021, 100, E24962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nissen, S.E.; Ni, W.; Shen, X.; Wang, Q.; Navar, A.M.; Nicholls, S.J.; Wolski, K.; Michael, L.; Haupt, A.; Krege, J.H. Lepodisiran—A Long-Duration Small Interfering RNA Targeting Lipoprotein(a). N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 392, 1673–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OCEAN(a) DOSE: Does Olpasiran Therapy Reduce Lipoprotein(a) Concentrations in Patients with ASCVD?—American College of Cardiology. Available online: https://www.acc.org/Latest-in-Cardiology/Articles/2022/11/01/22/00/sun-7pm-oceana-dose-aha-2022 (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- Liu, Y.; Jia, S.-D.; Yao, Y.; Tang, X.-F.; Xu, N.; Jiang, L.; Gao, Z.; Chen, J.; Yang, Y.-J.; Gao, R.-L.; et al. Impact of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein on coronary artery disease severity and outcomes in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. J. Cardiol. 2020, 75, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katamine, M.; Minami, Y.; Nagata, T.; Asakura, K.; Muramatsu, Y.; Kinoshita, D.; Fujiyoshi, K.; Ako, J. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein, plaque vulnerability and adverse events in patients with stable coronary disease: An optical coherence tomography study. Int. J. Cardiol. 2025, 421, 132924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, A.; Chiastra, C.; Gallo, D.; Loh, P.H.; Dokos, S.; Zhang, M.; Keramati, H.; Carbonaro, D.; Migliavacca, F.; Ray, T.; et al. Advancements in Coronary Bifurcation Stenting Techniques: Insights From Computational and Bench Testing Studies. Int. J. Numer. Methods Biomed. Eng. 2025, 41, e70000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahrori, Z.M.F.; Frazzetto, M.; Mahmud, S.H.; Alghwyeen, W.; Cortese, B. Drug-Coated Balloons: Recent Evidence and Upcoming Novelties. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2025, 12, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korjian, S.; McCarthy, K.J.; Larnard, E.A.; Cutlip, D.E.; McEntegart, M.B.; Kirtane, A.J.; Yeh, R.W. Drug-coated balloons in the management of coronary artery disease. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2024, 17, E013302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacoppo, D.; Gargiulo, G.; Aruta, P.; Capranzano, P.; Tamburino, C.; Capodanno, D. Treatment strategies for coronary in-stent restenosis: Systematic review and hierarchical Bayesian network meta-analysis of 24 randomised trials and 4880 patients. BMJ 2015, 351, h5392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, R.A.; Neumann, F.-J.; Mehilli, J.; Pinieck, S.; Wolff, B.; Tiroch, K.; Schulz, S.; Fusaro, M.; Ott, I.; Ibrahim, T.; et al. Paclitaxel-eluting balloons, paclitaxel-eluting stents, and balloon angioplasty in patients with restenosis after implantation of a drug-eluting stent (ISAR-DESIRE 3): A randomised, open-label trial. Lancet 2013, 381, 461–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortese, B.; Micheli, A.; Picchi, A.; Coppolaro, A.; Bandinelli, L.; Severi, S.; Limbruno, U. Paclitaxel-coated balloon versus drug-eluting stent during PCI of small coronary vessels, a prospective randomised clinical trial. The PICCOLETO study. Heart 2010, 96, 1291–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeger, R.V.; Farah, A.; Ohlow, M.-A.; Mangner, N.; Möbius-Winkler, S.; Leibundgut, G.; Weilenmann, D.; Wöhrle, J.; Richter, S.; Schreiber, M.; et al. Drug-coated balloons for small coronary artery disease (BASKET-SMALL 2): An open-label randomised non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2018, 392, 849–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheller, B.; Rissanen, T.T.; Farah, A.; Ohlow, M.-A.; Mangner, N.; Wöhrle, J.; Möbius-Winkler, S.; Weilenmann, D.; Leibundgut, G.; Cuculi, F.; et al. Drug-Coated Balloon for Small Coronary Artery Disease in Patients With and Without High-Bleeding Risk in the BASKET-SMALL 2 Trial. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2022, 15, E011569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jim, M.H.; Lee, M.K.Y.; Fung, R.C.Y.; Chan, A.K.C.; Chan, K.T.; Yiu, K.H. Six month angiographic result of supplementary paclitaxel-eluting balloon deployment to treat side branch ostium narrowing (SARPEDON). Int. J. Cardiol. 2015, 187, 594–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrador, J.A.; Fernandez, J.C.; Guzman, M.; Aragon, V. Drug-eluting vs. conventional balloon for side branch dilation in coronary bifurcations treated by provisional T stenting. J. Interv. Cardiol. 2013, 26, 454–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capodanno, D.; Alfonso, F.; Levine, G.N.; Valgimigli, M.; Angiolillo, D.J. ACC/AHA Versus ESC Guidelines on Dual Antiplatelet Therapy: JACC Guideline Comparison. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 72, 2915–2931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanini, G.G.; Byrne, R.A.; Windecker, S.; Kastrati, A. State of the art: Coronary artery stents—Past, present and future. EuroIntervention 2017, 13, 706–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefanini, G.G.; Holmes, D.R., Jr. Drug-Eluting Coronary-Artery Stents. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 254–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abizaid, A.; Costa, J.R. New drug-eluting stents an overview on biodegradable and polymer-free next-generation stent systems. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2010, 3, 384–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senst, B.; Goyal, A.; Basit, H.; Borger, J. Drug Eluting Stent Compounds. StatPearls. 2023. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537349/ (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Chiarito, M.; Sardella, G.; Colombo, A.; Briguori, C.; Testa, L.; Bedogni, F.; Fabbiocchi, F.; Paggi, A.; Palloshi, A.; Tamburino, C.; et al. Safety and efficacy of polymer-free drug-eluting stents: Amphilimus-eluting Cre8 versus biolimus-eluting biofreedom stents. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2019, 12, e007311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilgrim, T.; Muller, O.; Heg, D.; Roffi, M.; Kurz, D.J.; Moarof, I.; Weilenmann, D.; Kaiser, C.; Tapponnier, M.; Losdat, S.; et al. Biodegradable- Versus Durable-Polymer Drug-Eluting Stents for STEMI: Final 2-Year Outcomes of the BIOSTEMI Trial. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2021, 14, 639–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Bursill, C. When stents become plaques: In-stent neoatherosclerosis. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, M.E.; Yahagi, K.; Kolodgie, F.D.; Virmani, R. Neoatherosclerosis from a pathologist’s point of view. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2015, 35, e43–e49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, A.; Kirresh, A.; Ahmad, M.; Candilio, L. Robotic-Assisted PCI: The Future of Coronary Intervention? Cardiovasc. Revascularization Med. 2022, 35, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Göbölös, L.; Ramahi, J.; Obeso, A.; Bartel, T.; Hogan, M.; Traina, M.; Edris, A.; Hasan, F.; El Banna, M.; Tuzcu, E.M.; et al. Robotic Totally Endoscopic Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting: Systematic Review of Clinical Outcomes from the Past two Decades. Innovations 2019, 14, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisz, G.; Metzger, D.C.; Caputo, R.P.; Delgado, J.A.; Marshall, J.J.; Vetrovec, G.W.; Reisman, M.; Waksman, R.; Granada, J.F.; Novack, V.; et al. Safety and feasibility of robotic percutaneous coronary intervention: PRECISE (Percutaneous Robotically-Enhanced Coronary Intervention) Study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013, 61, 1596–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biso, S.M.R.; Vidovich, M.I. Radiation protection in the cardiac catheterization laboratory. J. Thorac. Dis. 2020, 12, 1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, T.M.; Shah, S.C.; Pancholy, S.B. Long Distance Tele-Robotic-Assisted Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: A Report of First-in-Human Experience. EClinicalMedicine 2019, 1, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, E.; Madder, R.D.; Wohns, D.H.; Schussler, J.M.; Salisbury, A.; Campbell, P.; Patel, T.M.; Lombardi, W.L.; Nicholson, W.J.; Parikh, M.A.; et al. Robotic-Assisted Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: Final Results of the PRECISION and PRECISION GRX Studies. J. Soc. Cardiovasc. Angiogr. Interv. 2025, 4, 103655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Garcia, C.; Ternent, L.; Homer, T.M.; Rodgers, H.; Bosomworth, H.; Shaw, L.; Aird, L.; Andole, S.; Cohen, D.; Dawson, J.; et al. Economic evaluation of robot-assisted training versus an enhanced upper limb therapy programme or usual care for patients with moderate or severe upper limb functional limitation due to stroke: Results from the RATULS randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e042081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roguin, A.; Wu, P.; Cohoon, T.; Gul, F.; Nasr, G.; Premyodhin, N.; Kern, M.J. Update on Radiation Safety in the Cath Lab—Moving Toward a “Lead-Free” Environment. J. Soc. Cardiovasc. Angiogr. Interv. 2023, 2, 101040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fazmin, I.T.; Ali, J.M. Hybrid Coronary Revascularisation: Indications, Techniques, and Outcomes. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Généreux, P.; Madhavan, M.V.; Mintz, G.S.; Maehara, A.; Palmerini, T.; Lasalle, L.; Xu, K.; McAndrew, T.; Kirtane, A.; Lansky, A.J.; et al. Ischemic outcomes after coronary intervention of calcified vessels in acute coronary syndromes. Pooled analysis from the HORIZONS-AMI (Harmonizing Outcomes With Revascularization and Stents in Acute Myocardial Infarction) and ACUITY (Acute Catheterization and Urgent Intervention Triage Strategy) TRIALS. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014, 63, 1845–1854. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Alfonso, F.; Bastante, T.; Antuña, P.; de la Cuerda, F.; Cuesta, J.; García-Guimaraes, M.; Rivero, F. Coronary Lithoplasty for the Treatment of Undilatable Calcified De Novo and In-Stent Restenosis Lesions. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2019, 12, 497–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi Galougahi, K.; Patel, S.; Shlofmitz, R.A.; Maehara, A.; Kereiakes, D.J.; Hill, J.M.; Stone, G.W.; Ali, Z.A. Calcific Plaque Modification by Acoustic Shock Waves: Intravascular Lithotripsy in Coronary Interventions. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2021, 14, E009354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeoh, J.; Cottens, D.; Cosgrove, C.; Mallek, K.; Strange, J.; Anderson, R.; Wilson, S.; Hanratty, C.; Walsh, S.; McEntegart, M.; et al. Management of stent underexpansion using intravascular lithotripsy-Defining the utility of a novel device. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2021, 97, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, S.J.; Ni, W.; Rhodes, G.M.; Nissen, S.E.; Navar, A.M.; Michael, L.F.; Haupt, A.; Krege, J.H. Oral Muvalaplin for Lowering of Lipoprotein(a): A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2025, 333, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donoghue, M.L.; Fazio, S.; Giugliano, R.P.; Stroes, E.S.G.; Kanevsky, E.; Gouni-Berthold, I.; Im, K.; Lira Pineda, A.; Wasserman, S.M.; Češka, R.; et al. Lipoprotein(a), PCSK9 inhibition, and cardiovascular risk insights from the FOURIER trial. Circulation 2019, 139, 1483–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridker, P.M.; Everett, B.M.; Thuren, T.; MacFadyen, J.G.; Chang, W.H.; Ballantyne, C.; Fonseca, F.; Nicolau, J.; Koenig, W.; Anker, S.D.; et al. Antiinflammatory Therapy with Canakinumab for Atherosclerotic Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 1119–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitt, B.; Steg, G.; Leiter, L.A.; Bhatt, D.L. The Role of Combined SGLT1/SGLT2 Inhibition in Reducing the Incidence of Stroke and Myocardial Infarction in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 2021, 36, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nidorf, S.M.; Fiolet, A.T.L.; Mosterd, A.; Eikelboom, J.W.; Schut, A.; Opstal, T.S.J.; The, S.H.K.; Xu, X.-F.; Ireland, M.A.; Lenderink, T.; et al. Colchicine in Patients with Chronic Coronary Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 1838–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ridker, P.M.; Everett, B.M.; Pradhan, A.; MacFadyen, J.G.; Solomon, D.H.; Zaharris, E.; Mam, V.; Hasan, A.; Rosenberg, Y.; Iturriaga, E.; et al. Low-Dose Methotrexate for the Prevention of Atherosclerotic Events. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 752–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, S.R.; Everett, B.M.; Birtcher, K.K.; Brown, J.M.; Januzzi, J.L.; Kalyani, R.R.; Kosiborod, M.; Magwire, M.; Morris, P.B.; Neumiller, J.J.; et al. 2020 Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on Novel Therapies for Cardiovascular Risk Reduction in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes: A Report of the American College of Cardiology Solution Set Oversight Committee. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 76, 1117–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, R.; Bhatt, D.L.; Szarek, M.; Cannon, C.P.; Leiter, L.A.; Inzucchi, S.E.; Lopes, R.D.; McGuire, D.K.; Lewis, J.B.; Riddle, M.C.; et al. Effect of sotagliflozin on major adverse cardiovascular events: A prespecified secondary analysis of the SCORED randomised trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2025, 13, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMurray, J.J.V.; Solomon, S.D.; Inzucchi, S.E.; Køber, L.; Kosiborod, M.N.; Martinez, F.A.; Ponikowski, P.; Sabatine, M.S.; Anand, I.S.; Bělohlávek, J.; et al. Dapagliflozin in Patients with Heart Failure and Reduced Ejection Fraction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 1995–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossello, X.; Gimenez, M.R. The dapagliflozin in patients with myocardial infarction (DAPA-MI) trial in perspective. Eur. Heart J. Acute Cardiovasc. Care 2023, 12, 862–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packer, M.P.; Anker, S.D.; Butler, J.; Filippatos, G.; Pocock, S.J.; Carson, P.; Januzzi, J.; Verma, S.; Tsutsui, H.; Brueckmann, M.; et al. Cardiovascular and Renal Outcomes with Empagliflozin in Heart Failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 1413–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, S. Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes. Z. Gefassmedizin 2016, 13, 17–18. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.; Ginsberg, H.N.; Choi, S.H. New, Novel Lipid-Lowering Agents for Reducing Cardiovascular Risk: Beyond Statins. Diabetes Metab. J. 2022, 46, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, M.D.; Tavori, H.; Fazio, S. PCSK9: From Basic Science Discoveries to Clinical Trials. Circ. Res. 2018, 122, 1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, S.A.; Naz, A.; Qamar Masood, M.; Shah, R. Meta-Analysis of Inclisiran for the Treatment of Hypercholesterolemia. Am. J. Cardiol. 2020, 134, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vignarajah, A.; Oro, P.; El Dahdah, J.; Vigneswaramoorthy, N.; Vest, A.R.; Shah, G. All-cause mortality and cardiovascular outcomes with glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists in patients with type 2 diabetes and heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Am. Heart J. Plus Cardiol. Res. Pract. 2025, 60, 100676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marso, S.P.; Daniels, G.H.; Brown-Frandsen, K.; Kristensen, P.; Mann, J.F.E.; Nauck, M.A.; Nissen, S.E.; Pocock, S.; Poulter, N.R.; Ravn, L.S.; et al. Liraglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. Drug Ther. Bull. 2016, 54, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoff, A.M.; Brown-Frandsen, K.; Colhoun, H.M.; Deanfield, J.; Emerson, S.S.; Esbjerg, S.; Hardt-Lindberg, S.; Hovingh, G.K.; Kahn, S.E.; Kushner, R.F.; et al. Semaglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Obesity without Diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 2221–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGuire, D.K.; Busui, R.P.; Deanfield, J.; Inzucchi, S.E.; Mann, J.F.E.; Marx, N.; Mulvagh, S.L.; Poulter, N.; Engelmann, M.D.M.; Hovingh, G.K.; et al. Effects of oral semaglutide on cardiovascular outcomes in individuals with type 2 diabetes and established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and/or chronic kidney disease: Design and baseline characteristics of SOUL, a randomized trial. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2023, 25, 1932–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.S.; Hwang, J.; Yon, D.K.; Lee, S.W.; Jung, S.Y.; Park, S.; Johnson, C.O.; Stark, B.A.; Razo, C.; Abbasian, M.; et al. Global burden of peripheral artery disease and its risk factors, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Glob. Health 2023, 11, e1553–e1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.-K.; Hong, S.-J.; Lee, Y.-J.; Hong, S.J.; Yun, K.H.; Hong, B.-K.; Heo, J.H.; Rha, S.-W.; Cho, Y.-H.; Lee, S.-J.; et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of moderate-intensity statin with ezetimibe combination therapy versus high-intensity statin monotherapy in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (RACING): A randomised, open-label, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2022, 400, 380–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamargo, I.A.; Baek, K.I.; Kim, Y.; Park, C.; Jo, H. Flow-induced reprogramming of endothelial cells in atherosclerosis. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2023, 20, 738–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Tang, M.; Ho, W.; Teng, Y.; Chen, Q.; Bu, L.; Xu, X.; Zhang, X.-Q. Modulating Plaque Inflammation via Targeted mRNA Nanoparticles for the Treatment of Atherosclerosis. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 17721–17739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Lan, X.; Zhang, Y.; Fu, C.; Liu, L.; Cao, F.; Guo, W. Biomimetic nanomedicines for precise atherosclerosis theranostics. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2022, 13, 4442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nankivell, V.; Vidanapathirana, A.K.; Hoogendoorn, A.; Tan, J.T.M.; Verjans, J.; Psaltis, P.J.; Hutchinson, M.R.; Gibson, B.C.; Lu, Y.; Goldys, E.; et al. Targeting macrophages with multifunctional nanoparticles to detect and prevent atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc. Res. 2024, 120, 819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Pang, Z.; Li, J.; Anh, M.; Kim, B.S.; Gao, G. Bioengineered human arterial equivalent and its applications from vascular graft to in vitro disease modeling. iScience 2024, 27, 111215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Yuan, W.; Yu, B.; Kuai, R.; Hu, W.; Morin, E.E.; Garcia-Barrio, M.T.; Zhang, J.; Moon, J.J.; Schwendeman, A.; et al. Synthetic High-Density Lipoprotein-Mediated Targeted Delivery of Liver X Receptors Agonist Promotes Atherosclerosis Regression. EBioMedicine 2017, 28, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Lin, R.; Lin, H.B.; Shen, S. Nanomedicine-based drug delivery strategies for the treatment of atherosclerosis. Med. Drug Discov. 2024, 22, 100189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The University of Edinburgh. Artificial Blood Vessels Could Improve Heart Bypass Outcomes. Available online: https://www.ed.ac.uk/news/2024/artificial-blood-vessels-could-improve-heart-bypas (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- Lang, Z.; Chen, T.; Zhu, S.; Wu, X.; Wu, Y.; Miao, X.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, L.; Zhu, Z.; Xu, R.X. Construction of vascular grafts based on tissue-engineered scaffolds. Mater. Today Bio 2024, 29, 101336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratner, B. Vascular Grafts: Technology Success/Technology Failure. BME Front. 2023, 4, 0003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, A.S.-R.; Dinesh, T.; Pang, N.Y.-L.; Dinesh, V.; Pang, K.Y.-L.; Yong, C.L.; Lee, S.J.J.; Yip, G.W.; Bay, B.H.; Srinivasan, D.K. Nanoparticles as Drug Delivery Systems for the Targeted Treatment of Atherosclerosis. Molecules 2024, 29, 2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ‘This is Revolutionary!’: Breakthrough Cholesterol Treatment Can Cut Levels by 69% After One Dose. BBC Science Focus Magazine. Available online: https://www.sciencefocus.com/news/new-cholesterol-treatment-could-be-revolutionary-verve (accessed on 23 December 2025).

- Shakya, S.; Shrestha, A.; Robinson, S.; Randall, S.; Mnatzaganian, G.; Brown, H.; Boyd, J.; Xu, D.; Lee, C.M.Y.; Brumby, S.; et al. Global comparison of the economic costs of coronary heart disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2025, 15, e084917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Agamy, S.; Zaghloul, S.; Khan, Z.; Shahin, A.; Kishk, R.; Smman, A.; Candilio, L. Innovations in Diagnosis and Treatment of Coronary Artery Disease. Diagnostics 2026, 16, 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010098

Agamy S, Zaghloul S, Khan Z, Shahin A, Kishk R, Smman A, Candilio L. Innovations in Diagnosis and Treatment of Coronary Artery Disease. Diagnostics. 2026; 16(1):98. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010098

Chicago/Turabian StyleAgamy, Salaheldin, Sheref Zaghloul, Zahid Khan, Ahmed Shahin, Ramy Kishk, Ahmed Smman, and Luciano Candilio. 2026. "Innovations in Diagnosis and Treatment of Coronary Artery Disease" Diagnostics 16, no. 1: 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010098

APA StyleAgamy, S., Zaghloul, S., Khan, Z., Shahin, A., Kishk, R., Smman, A., & Candilio, L. (2026). Innovations in Diagnosis and Treatment of Coronary Artery Disease. Diagnostics, 16(1), 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010098