Exploring the Role of Cerebrospinal Fluid and Serum Mid-Regional Pro-Adrenomedullin in Tick-Borne Encephalitis: A Pilot Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Ethical Approval

2.2. Participants and Samples

2.3. MR-proADM Measurement

2.4. Other Laboratory Measurements

2.5. Statistical Analysis

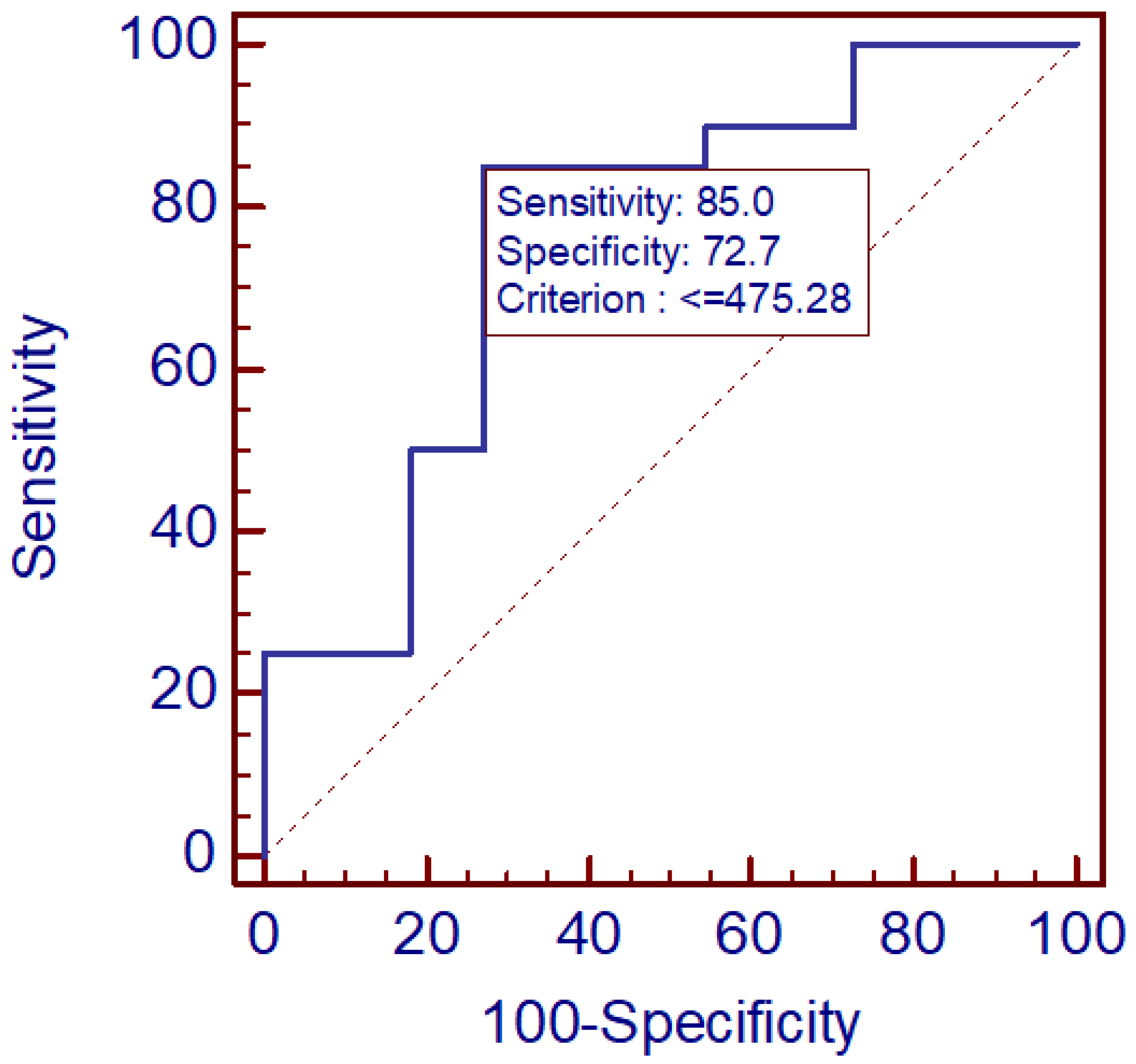

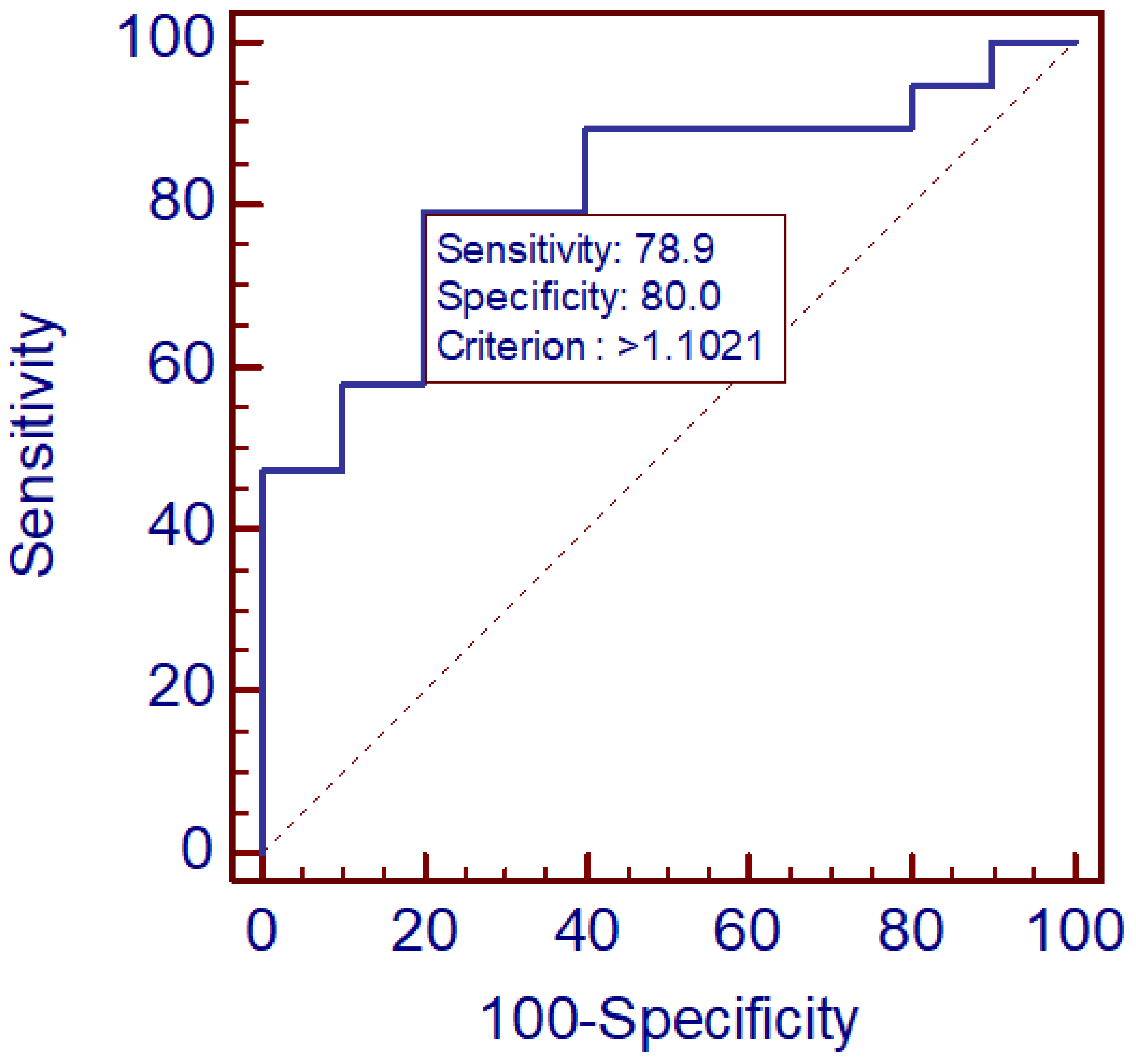

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Corr, M.P.; Fairley, D.; McKenna, J.P.; Shields, M.D.; Waterfield, T. Diagnostic value of mid-regional pro-Adrenomedullin as a biomarker of invasive bacterial infection in children: A systematic review. BMC Pediatr. 2022, 22, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iriarte, A.; Ochoa-Callejero, L.; García-Sanmartín, J.; Cerdà, P.; Garrido, P.; Narro-Íñiguez, J.; Mora-Luján, J.; Jucglà, A.; Sánchez-Corral, M.; Cruellas, F.; et al. Adrenomedullin as a potential biomarker involved in patients with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2021, 88, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayes-Genis, A.; Greene, S.J. Bio-adrenomedullin: A weak biomarker for a STRONG patient. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2024, 26, 1493–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trojan, G.; Moniuszko-Malinowska, A.; Grzeszczuk, A.; Czupryna, P. Adrenomedullin as a new prosperous biomarker in infections: Current and future perspectives. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 6142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janes, F.; Siega, P.D.; Comar, M.; Furlani, M.; Fortes, A.Z.; Visentini, D.; Ripoli, A.; Sbrana, F.; Carannante, N.; Leonardi, S.; et al. Mid-regional proadrenomedullin in cerebrospinal fluid is a reliable diagnostic and prognostic marker for acute meningoencephalitis and neurological disorders. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2025, 39, e70110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chen, K.; Liu, R.; Zheng, Z.; Hou, X. Antimicrobial neuropeptides and their therapeutic potential in vertebrate brain infectious disease. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1496147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzain, M.; Daghistani, H.; Shamrani, T.; Almoghrabi, Y.; Daghistani, Y.; Alharbi, O.S.; Sait, A.M.; Mufrrih, M.; Alhazmi, W.; Alqarni, M.A.; et al. Antimicrobial peptides: Mechanisms, applications, and therapeutic potential. Infect. Drug Resist. 2025, 18, 4385–4426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geven, C.; Kox, M.; Pickkers, P. Adrenomedullin and adrenomedullin-targeted therapy as treatment strategies relevant for sepsis. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spoto, S.; Basili, S.; Cangemi, R.; Yuste, J.R.; Lucena, F.; Romiti, G.F.; Raparelli, V.; Argemi, J.; D’avanzo, G.; Locorriere, L.; et al. A focus on the pathophysiology of adrenomedullin expression: Endothelitis and organ damage in severe viral and bacterial infections. Cells 2024, 13, 892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massimini, M.; Bachetti, B.; Dalle Vedove, E.; Benvenga, A.; Di Pierro, F.; Bernabò, N. A set of dysregulated target genes to reduce neuroinflammation at molecular level. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Lu, Y.; Fang, W.; Huang, Y.; Li, Q.; Xu, Z. Neurodegenerative diseases and neuroinflammation-induced apoptosis. Open Life Sci. 2025, 20, 20221051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogovic, P.; Strle, F. Tick-borne encephalitis: A review of epidemiology, clinical characteristics, and management. World J. Clin. Cases 2015, 3, 430–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Country Profile: Poland. Tick-Borne Encephalitis (TBE). 1 August 2012. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/country-profile-poland-tick-borne-encephalitis-tbe (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Katargina, O.; Russakova, S.; Geller, J.; Kondrusik, M.; Zajkowska, J.; Zygutiene, M.; Bormane, A.; Trofimova, J.; Golovljova, I. Detection and characterization of tick-borne encephalitis virus in Baltic countries and eastern Poland. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czarnowska, A.; Groth, M.; Okrzeja, J.; Garkowski, A.; Kristoferitsch, W.; Kułakowska, A.; Zajkowska, J. A fatal case of tick-borne encephalitis in an immunocompromised patient: Case report from Northeastern Poland and review of literature. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2024, 15, 102273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiffi, G.; Grandgirard, D.; Leib, S.L.; Chrdle, A.; Růžek, D. Tick-borne encephalitis: A comprehensive review of the epidemiology, virology, and clinical picture. Rev. Med. Virol. 2023, 33, e2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamczuk, J.; Chlabicz, M.; Koda, N.; Kondrusik, M.; Zajkowska, J.; Czupryna, P.; Moniuszko-Malinowska, A. Severe cases of tick-borne encephalitis in northeastern Poland. Pathogens 2024, 14, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suyama, S.; Boxall, S.; Grace, B.; Fořtová, A.; Pychova, M.; Krbkova, L.; Mandal, R.; Wishart, D.; Griffin, D.E.; Růžek, D.; et al. Changes in metabolite profiles in the cerebrospinal fluid and in human neuronal cells upon tick-borne encephalitis virus infection. J. Neuroinflamm. 2025, 22, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiffi, G.; Grandgirard, D.; Sendi, P.; Dietmann, A.; Bassetti, C.L.A.; Leib, S.L. Sleep-wake and circadian disorders after tick-borne encephalitis. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czupryna, P.; Grygorczuk, S.; Krawczuk, K.; Pancewicz, S.; Zajkowska, J.; Dunaj, J.; Matosek, A.; Kondrusik, M.; Moniuszko-Malinowska, A. Sequelae of tick-borne encephalitis in retrospective analysis of 1072 patients. Epidemiol. Infect. 2018, 146, 1663–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halsby, K.; Gildea, L.; Zhang, P.; Angulo, F.J.; Pilz, A.; Moisi, J.; Colosia, A.; Sellner, J. Clinical spectrum and dynamics of sequelae following tick-borne encephalitis virus infection: A systematic literature review. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2025, 12, ofaf317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fialek, B.; De Roquetaillade, C.; Pruc, M.; Navolokina, A.; Chirico, F.; Ladny, J.R.; Peacock, F.W.; Szarpak, L. Systematic review with meta-analysis of mid-regional pro-adrenomedullin (MR-proadm) as a prognostic marker in COVID-19-hospitalized patients. Ann. Med. 2023, 55, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montrucchio, G.; Sales, G.; Balzani, E.; Lombardo, D.; Giaccone, A.; Cantù, G.; D’ANtonio, G.; Rumbolo, F.; Corcione, S.; Simonetti, U.; et al. Effectiveness of mid-regional pro-adrenomedullin, compared to other biomarkers (including lymphocyte subpopulations and immunoglobulins), as a prognostic biomarker in COVID-19 critically ill patients: New evidence from a 15-month observational prospective study. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1122367. [Google Scholar]

- Haag, E.; Gregoriano, C.; Molitor, A.; Kloter, M.; Kutz, A.; Mueller, B.; Schuetz, P. Does mid-regional pro-adrenomedullin (MR-proADM) improve the sequential organ failure assessment-score (SOFA score) for mortality-prediction in patients with acute infections? Results of a prospective observational study. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2021, 59, 1165–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.Y.; Wang, F.Z.; Chang, R.; Wang, Q.; Liu, S.-Y.; Cheng, Z.-X.; Gao, Q.; Zhou, H.; Zhou, Y.-B. Adrenomedullin improves hypertension and vascular remodeling partly through the receptor-mediated AMPK pathway in rats with obesity-related hypertension. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.L.; Cai, Z.; Hsu, S.Y.T. Sustained activation of CLR/RAMP receptors by gel-forming agonists. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geven, C.; Bergmann, A.; Kox, M.; Pickkers, P. Vascular Effects of Adrenomedullin and the Anti-Adrenomedullin Anti-body Adrecizumab in Sepsis. Shock 2018, 50, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takata, F.; Nakagawa, S.; Matsumoto, J.; Dohgu, S. Blood-brain barrier dysfunction amplifies the development of neuroinflammation: Understanding of cellular events in brain microvascular endothelial cells for prevention and treatment of BBB dysfunction. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 661838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, S.; Cao, H.; Huang, Y.; Shi, Z.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, S.; Shi, H.; Gao, Y. ASK1-K716R reduces neuroinflammation and white matter injury via preserving blood-brain barrier integrity after traumatic brain injury. J. Neuroinflamm. 2023, 20, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N.; Kiran, P.V.S.; Khalid, M.; Kumar, T.P.; Ravindra, P.; Bhat, R. Role of biomarkers in predicting mortality in patients with flaviviral disease endemic to South India: A retrospective observational study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, 1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overby, A.K.; Popov, V.L.; Niedrig, M.; Weber, F. Tick-borne encephalitis virus delays interferon induction and hides its double-stranded RNA in intracellular membrane vesicles. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 8470–8483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gervais, A.; Marchal, A.; Fortova, A.; Berankova, M.; Krbkova, L.; Pychova, M.; Salat, J.; Zhao, S.; Kerrouche, N.; Le Voyer, T.; et al. Autoantibodies neutralizing type I IFNs underlie severe tick-borne encephalitis in ∼10% of patients. J. Exp. Med. 2024, 221, e20240637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Yang, W.; Wang, S.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, W.; Shi, M.; Li, Y. Adrenomedullin in tumorigenesis and cancer progression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Herrero, S.; Martínez, A. Adrenomedullin: Not just another gastrointestinal peptide. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.; Sanyal, S.; Basant, N.; Sanyal, S. An updated review of potential drug targets for Japanese encephalitis. Cent. Nerv. Syst. Agents Med. Chem. 2025, 26, 46–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, P.; Chauhan, P.; Pandey, S.; Lakhanpal, S.; Padmapriya, G.; Mishra, S.; Kaur, M.; Ashraf, A.; Kumar, M.R.; Ramniwas, S.; et al. An updated review on nipah virus infection with a focus on encephalitis, vasculitis, and therapeutic approaches. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2025, 25, 2164–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, R.; Bakay, M.; Hakonarson, H. Suppressor of cytokine signaling mimetics as a therapeutic approach in autoimmune encephalitis. Eur. J. Immunol. 2025, 55, e70023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bálint, L.; Nelson-Maney, N.P.; Tian, Y.; Serafin, S.D.; Caron, K.M. Clinical potential of adrenomedullin signaling in the cardiovascular system. Circ. Res. 2023, 132, 1185–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.L.; Belousoff, M.J.; Fletcher, M.M.; Zhang, X.; Khoshouei, M.; Deganutti, G.; Koole, C.; Furness, S.G.B.; Miller, L.J.; Hay, D.L.; et al. Structure and dynamics of adrenomedullin receptors AM1 and AM2 reveal key mechanisms in the control of receptor phenotype by receptor activity-modifying proteins. ACS. Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2020, 3, 263–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Yuan, H.; Yang, X.; Lei, Y.; Lian, J. Glutamine-glutamate centered metabolism as the potential therapeutic target against Japanese encephalitis virus-induced encephalitis. Cell Biosci. 2025, 15, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; He, L.; Dinger, B.; Stensaas, L.; Fidone, S. Sustained exposure to cytokines and hypoxia enhances excitability of oxygen-sensitive type I cells in rat carotid body: Correlation with the expression of HIF-1α protein and adrenomedullin. High Alt. Med. Biol. 2013, 14, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata-Greenwood, E.; Goyal, D.; Goyal, R. Comparative and experimental studies on the genes altered by chronic hypoxia in human brain microendothelial cells. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, M.; Boruah, A.P.; Thakur, K.T. Acute neurologic emerging flaviviruses. Ther. Adv. Infect. Dis. 2022, 9, 20499361221102664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, R. Tick-borne encephalitis—Still a serious disease? Wien. Med. Wochenschr. 2012, 162, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group | MR-proADM Level [pmol/L] | n | Mean | Median | Min | Max | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TBE | Cerebrospinal fluid 1 (CSF1) | 20 | 730.74 | 666.62 | 101.00 | 1678.79 | 383.68 |

| Serum 1 (SER1) | 20 | 402.00 | 357.65 | 130.42 | 1091.42 | 243.37 | |

| Cerebrospinal fluid 2 (CSF2) | 20 | 552.76 | 530.87 | 276.37 | 1149.48 | 223.03 | |

| Serum 2 (SER2) | 20 | 645.81 | 633.33 | 335.39 | 1201.70 | 225.56 | |

| Control | Cerebrospinal fluid 1 (CSF1) | 14 | 709.13 | 780.49 | 102.00 | 1437.59 | 370.59 |

| Serum 1 (SER1) | 11 | 2534.71 | 725.99 | 256.95 | 20,898.60 | 6099.333 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Trojan, G.; Moniuszko-Malinowska, A.; Oklińska, J.; Pawlak-Zalewska, W.; Kruszewska, E.; Kulczyńska-Przybik, A.; Mroczko, B.; Czupryna, P. Exploring the Role of Cerebrospinal Fluid and Serum Mid-Regional Pro-Adrenomedullin in Tick-Borne Encephalitis: A Pilot Study. Diagnostics 2026, 16, 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010095

Trojan G, Moniuszko-Malinowska A, Oklińska J, Pawlak-Zalewska W, Kruszewska E, Kulczyńska-Przybik A, Mroczko B, Czupryna P. Exploring the Role of Cerebrospinal Fluid and Serum Mid-Regional Pro-Adrenomedullin in Tick-Borne Encephalitis: A Pilot Study. Diagnostics. 2026; 16(1):95. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010095

Chicago/Turabian StyleTrojan, Gabriela, Anna Moniuszko-Malinowska, Joanna Oklińska, Wioletta Pawlak-Zalewska, Ewelina Kruszewska, Agnieszka Kulczyńska-Przybik, Barbara Mroczko, and Piotr Czupryna. 2026. "Exploring the Role of Cerebrospinal Fluid and Serum Mid-Regional Pro-Adrenomedullin in Tick-Borne Encephalitis: A Pilot Study" Diagnostics 16, no. 1: 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010095

APA StyleTrojan, G., Moniuszko-Malinowska, A., Oklińska, J., Pawlak-Zalewska, W., Kruszewska, E., Kulczyńska-Przybik, A., Mroczko, B., & Czupryna, P. (2026). Exploring the Role of Cerebrospinal Fluid and Serum Mid-Regional Pro-Adrenomedullin in Tick-Borne Encephalitis: A Pilot Study. Diagnostics, 16(1), 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010095