Acute Kidney Injury Biomarkers in Perioperative Care: A Scoping Review of Clinical Implementation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Current State of AKI Biomarker Research

3.1. Functional Biomarkers and Surrogate Markers of the Glomerular Filtration Rate

3.1.1. PENK

3.1.2. IL-18

3.1.3. L-FABP

3.2. Stress Biomarkers

TIMP-2 and IGFBP-7

3.3. Injury and Damage Biomarkers

3.3.1. C-C Motif Chemokine Ligand-14

3.3.2. C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand-9

3.3.3. Dickkopf-Related Protein-3

3.3.4. Chitinase 3-like Protein-1

3.3.5. Kidney Injury Molecule-1

3.3.6. Cystatin C

3.3.7. Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin

3.3.8. Alpha-1-Microglobulin

3.3.9. Hepcidin-25

3.3.10. Gamma-Glutamyltransferase

3.3.11. π-Glutathione S-Transferase

3.3.12. Interleukin-9

3.3.13. Monocyte Chemoattractant Peptide-1

3.3.14. Netrin-1

3.3.15. Semaphorin-3A

3.3.16. Osteopontin

3.4. Renal Tubular Epithelial Cells

3.5. Factors Affecting Biomarker Specificity: False Positives and False Negatives

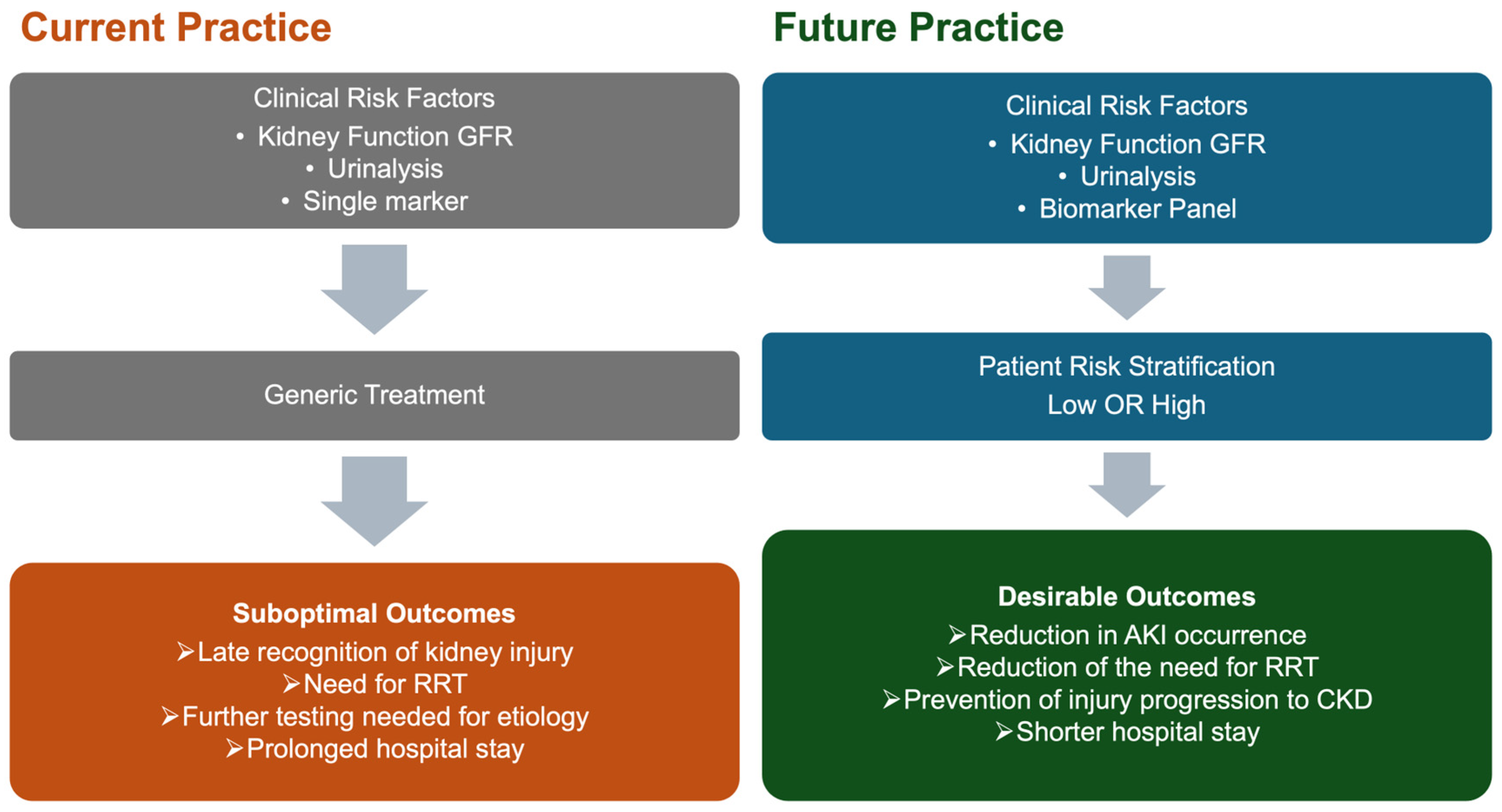

4. Biomarker Panel

5. Regulatory Approval and Clinical Adaptation

Regulatory Approval Status

6. AKI Care Bundle Implementation and Biomarker Panels

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| α1m | Alpha-1-microglobulin |

| AIN | Acute interstitial nephritis |

| AKI | Acute kidney injury |

| AUC | Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve |

| CBP | Cardiopulmonary bypass |

| CCL-14 | C-C motif chemokine ligand-14 |

| CHI3L-1 | Chitinase 3-like protein-1 |

| CI-AKI | Contrast-induced acute kidney injury |

| CKD | Chronic kidney disease |

| CysC | Cystatin C |

| CXCL-9 | C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 9 |

| DKK-3 | Dickkopf-related protein-3 |

| DOR | Diagnostic odds ratios |

| eGFR | Estimated glomerular filtration rate |

| EMA | European Medicines Agency |

| FDA | U.S. Food and Drug Administration |

| GFR | Glomerular filtration rate |

| GGT | Gamma-glutamyltransferase |

| IGFBP-7 | Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 7 |

| IL-18 | Interleukin-18 |

| IL-9 | Interleukin-9 |

| KDIGO | Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes |

| KIM-1 | Kidney injury molecule-1 |

| L-FABP | Liver-type fatty acid-binding protein |

| MAKE | Major adverse kidney events |

| MCP-1 | Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 |

| NGAL | Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin |

| NICE | National Institute for Health and Care Excellence |

| NTN-1 | Netrin-1 |

| OPN | Osteopontin |

| pAKI | Persistent acute kidney injury |

| PENK | Proenkephalin A 119–159 |

| π-GST | π-Glutathione S-transferase |

| RRT | Renal replacement therapy |

| RTECs | Renal tubular epithelial cells |

| sAKI | Subclinical acute kidney injury |

| SCr | Serum creatinine |

| SEMA-3A | Semaphorin-3A |

| TIMP-2 | Tissue inhibitor of metalloprotease-2 |

| UOP | Urine output |

References

- Hobson, C.; Ozrazgat-Baslanti, T.; Kuxhausen, A.; Thottakkara, P.; Efron, P.A.; Moore, F.A.; Moldawer, L.L.; Segal, M.S.; Bihorac, A. Cost and Mortality Associated With Postoperative Acute Kidney Injury. Ann. Surg. 2015, 261, 1207–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyner, J.L.; Mackey, R.H.; Rosenthal, N.A.; Carabuena, L.A.; Kampf, J.P.; Echeverri, J.; McPherson, P.; Blackowicz, M.J.; Rodriguez, T.; Sanghani, A.R.; et al. Health Care Resource Utilization and Costs of Persistent Severe Acute Kidney Injury (PS-AKI) Among Hospitalized Stage 2/3 AKI Patients. Kidney360 2023, 4, 316–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khwaja, A. KDIGO Clinical Practice Guidelines for Acute Kidney Injury. Nephron 2012, 120, c179–c184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostermann, M.; Bellomo, R.; Burdmann, E.A.; Doi, K.; Endre, Z.H.; Goldstein, S.L.; Kane-Gill, S.L.; Liu, K.D.; Prowle, J.R.; Shaw, A.D.; et al. Controversies in Acute Kidney Injury: Conclusions from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Conference. Kidney Int. 2020, 98, 294–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lameire, N.H.; Levin, A.; Kellum, J.A.; Cheung, M.; Jadoul, M.; Winkelmayer, W.C.; Stevens, P.E.; Caskey, F.J.; Farmer, C.K.T.; Ferreiro Fuentes, A.; et al. Harmonizing Acute and Chronic Kidney Disease Definition and Classification: Report of a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Consensus Conference. Kidney Int. 2021, 100, 516–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, M.; Kellum, J.A.; Ronco, C. Subclinical AKI—An Emerging Syndrome with Important Consequences. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2012, 8, 735–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrezenmeier, E.V.; Barasch, J.; Budde, K.; Westhoff, T.; Schmidt-Ott, K.M. Biomarkers in Acute Kidney Injury—Pathophysiological Basis and Clinical Performance. Acta Physiol. 2017, 219, 556–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostermann, M.; Legrand, M.; Meersch, M.; Srisawat, N.; Zarbock, A.; Kellum, J.A. Biomarkers in Acute Kidney Injury. Ann. Intensive Care 2024, 14, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endre, Z.H. Biomarkers of Acute Kidney Injury: Time to Learn from Implementations. Crit. Care Resusc. J. Australas. Acad. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 23, 137–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffin, B.R.; Faubel, S.; Edelstein, C.L. Biomarkers of Drug-Induced Kidney Toxicity. Ther. Drug Monit. 2019, 41, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matarneh, A.; Akkari, A.; Sardar, S.; Salameh, O.; Dauleh, M.; Matarneh, B.; Abdulbasit, M.; Miller, R.; Verma, N.; Ghahramani, N. Beyond Creatinine: Diagnostic Accuracy of Emerging Biomarkers for AKI in the ICU—A Systematic Review. Ren. Fail. 2025, 47, 2556295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F.R.; Al-Yateem, N.; Nejadghaderi, S.A.; Gamil, R.; AbuRuz, M.E. Effect of Acute Kidney Injury Care Bundle on Kidney Outcomes in Cardiac Patients Receiving Critical Care: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Nephrol. 2025, 26, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, F.; Wang, L.; Luo, Q. Effect of Care Bundles for Acute Kidney Injury: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0302179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumbert, S.D.; Kork, F.; Jackson, M.L.; Vanga, N.; Ghebremichael, S.J.; Wang, C.Y.; Eltzschig, H.K. Perioperative Acute Kidney Injury. Anesthesiology 2020, 132, 180–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kashani, K.; Rosner, M.H.; Ostermann, M. Creatinine: From Physiology to Clinical Application. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2020, 72, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostermann, M.; Zarbock, A.; Goldstein, S.; Kashani, K.; Macedo, E.; Murugan, R.; Bell, M.; Forni, L.; Guzzi, L.; Joannidis, M.; et al. Recommendations on Acute Kidney Injury Biomarkers From the Acute Disease Quality Initiative Consensus Conference: A Consensus Statement. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2019209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beunders, R.; Donato, L.J.; van Groenendael, R.; Arlt, B.; Carvalho-Wodarz, C.; Schulte, J.; Coolen, A.C.; Lieske, J.C.; Meeusen, J.W.; Jaffe, A.S.; et al. Assessing GFR With Proenkephalin. Kidney Int. Rep. 2023, 8, 2345–2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khorashadi, M.; Beunders, R.; Pickkers, P.; Legrand, M. Proenkephalin: A New Biomarker for Glomerular Filtration Rate and Acute Kidney Injury. Nephron 2020, 144, 655–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.-C.; Chuan, M.-H.; Liu, J.-H.; Liao, H.-W.; Ng, L.L.; Magnusson, M.; Jujic, A.; Pan, H.-C.; Wu, V.-C.; Forni, L.G. Proenkephalin as a Biomarker Correlates with Acute Kidney Injury: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis and Trial Sequential Analysis. Crit. Care 2023, 27, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsiras, D.; Ventoulis, I.; Verras, C.; Bistola, V.; Bezati, S.; Fyntanidou, B.; Polyzogopoulou, E.; Parissis, J.T. Proenkephalin 119-159 in Heart Failure: From Pathophysiology to Clinical Implications. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollinger, A.; Wittebole, X.; François, B.; Pickkers, P.; Antonelli, M.; Gayat, E.; Chousterman, B.G.; Lascarrou, J.-B.; Dugernier, T.; Di Somma, S.; et al. Proenkephalin A 119-159 (Penkid) Is an Early Biomarker of Septic Acute Kidney Injury: The Kidney in Sepsis and Septic Shock (Kid-SSS) Study. Kidney Int. Rep. 2018, 3, 1424–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, K.S.; Taub, P.; Patel, M.; Rehfeldt, M.; Struck, J.; Clopton, P.; Mehta, R.L.; Maisel, A.S. Proenkephalin Predicts Acute Kidney Injury in Cardiac Surgery Patients. Clin. Nephrol. 2015, 83, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breidthardt, T.; Jaeger, C.; Christ, A.; Klima, T.; Mosimann, T.; Twerenbold, R.; Boeddinghaus, J.; Nestelberger, T.; Badertscher, P.; Struck, J.; et al. Proenkephalin for the Early Detection of Acute Kidney Injury in Hospitalized Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 48, e12999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gombert, A.; Barbati, M.; Hartmann, O.; Schulte, J.; Simon, T.; Simon, F. Proenkephalin A 119–159 May Predict Post-Operative Acute Kidney Injury and in Hospital Mortality Following Open or Endovascular Thoraco-Abdominal Aortic Repair. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2020, 60, 493–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walczak-Wieteska, P.; Zuzda, K.; Małyszko, J.; Andruszkiewicz, P. Proenkephalin A 119-159 as an Early Biomarker of Acute Kidney Injury in Complex Endovascular Aortic Repair: An Explorative Single-Center Cross-Sectional Study with the Utilization of Two Measurement Methods. Perioper. Med. 2025, 14, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walczak-Wieteska, P.; Zuzda, K.; Małyszko, J.; Andruszkiewicz, P. Proenkephalin A 119–159 in Perioperative and Intensive Care—A Promising Biomarker or Merely Another Option? Diagnostics 2024, 14, 2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mossanen, J.C.; Pracht, J.; Jansen, T.U.; Buendgens, L.; Stoppe, C.; Goetzenich, A.; Struck, J.; Autschbach, R.; Marx, G.; Tacke, F. Elevated Soluble Urokinase Plasminogen Activator Receptor and Proenkephalin Serum Levels Predict the Development of Acute Kidney Injury after Cardiac Surgery. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VanderBrink, B.A.; Asanuma, H.; Hile, K.; Zhang, H.; Rink, R.C.; Meldrum, K.K. Interleukin-18 Stimulates a Positive Feedback Loop during Renal Obstruction via Interleukin-18 Receptor. J. Urol. 2011, 186, 1502–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnikov, V.Y.; Ecder, T.; Fantuzzi, G.; Siegmund, B.; Lucia, M.S.; Dinarello, C.A.; Schrier, R.W.; Edelstein, C.L. Impaired IL-18 Processing Protects Caspase-1–Deficient Mice from Ischemic Acute Renal Failure. J. Clin. Investig. 2001, 107, 1145–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverton, N.A.; Hall, I.E.; Melendez, N.P.; Harris, B.; Harley, J.S.; Parry, S.R.; Lofgren, L.R.; Stoddard, G.J.; Hoareau, G.L.; Kuck, K. Intraoperative Urinary Biomarkers and Acute Kidney Injury After Cardiac Surgery. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2021, 35, 1691–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, M.; Bellomo, R.; Story, D.; Davenport, P.; Haase-Fielitz, A. Urinary Interleukin-18 Does Not Predict Acute Kidney Injury after Adult Cardiac Surgery: A Prospective Observational Cohort Study. Crit. Care 2008, 12, R96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, Z.; Li, H.; Jiao, P.; Jiang, L.; Geng, J.; Yang, Q.; Liao, R.; Su, B. The Value of Urinary Interleukin-18 in Predicting Acute Kidney Injury: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ren. Fail. 2022, 44, 1727–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Xiao, Y.; Yao, Y.; Xu, G.; Li, C.; Zhang, Q.; Li, H.; Han, L. Comparison of Urinary Biomarkers for Early Detection of Acute Kidney Injury after Cardiopulmonary Bypass Surgery in Infants and Young Children. Pediatr. Cardiol. 2013, 34, 880–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parikh, C.R.; Coca, S.G.; Thiessen-Philbrook, H.; Shlipak, M.G.; Koyner, J.L.; Wang, Z.; Edelstein, C.L.; Devarajan, P.; Patel, U.D.; Zappitelli, M.; et al. Postoperative Biomarkers Predict Acute Kidney Injury and Poor Outcomes after Adult Cardiac Surgery. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. JASN 2011, 22, 1748–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamijo-Ikemori, A.; Sugaya, T.; Yasuda, T.; Kawata, T.; Ota, A.; Tatsunami, S.; Kaise, R.; Ishimitsu, T.; Tanaka, Y.; Kimura, K. Clinical Significance of Urinary Liver-Type Fatty Acid-Binding Protein in Diabetic Nephropathy of Type 2 Diabetic Patients. Diabetes Care 2011, 34, 691–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilnes, B.; Castello-Branco, B.; Branco, B.C.; Sanglard, A.; Vaz De Castro, P.A.S.; Simões-e-Silva, A.C. Urinary L-FABP as an Early Biomarker for Pediatric Acute Kidney Injury Following Cardiac Surgery with Cardiopulmonary Bypass: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portilla, D.; Dent, C.; Sugaya, T.; Nagothu, K.K.; Kundi, I.; Moore, P.; Noiri, E.; Devarajan, P. Liver Fatty Acid-Binding Protein as a Biomarker of Acute Kidney Injury after Cardiac Surgery. Kidney Int. 2008, 73, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Lee, C.-C.; Chen, J.-J.; Fan, P.-C.; Tu, Y.-R.; Yen, C.-L.; Kuo, G.; Chen, S.-W.; Tsai, F.-C.; Chang, C.-H. Assessment of Cardiopulmonary Bypass Duration Improves Novel Biomarker Detection for Predicting Postoperative Acute Kidney Injury after Cardiovascular Surgery. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, K.; Kamijo-Ikemori, A.; Sugaya, T.; Yasuda, T.; Kimura, K. Usefulness of Urinary Biomarkers in Early Detection of Acute Kidney Injury After Cardiac Surgery in Adults. Circ. J. 2012, 76, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Che, M.; Xue, S.; Xie, B.; Zhu, M.; Lu, R.; Zhang, W.; Qian, J.; Yan, Y. Urinary L-FABP and Its Combination with Urinary NGAL in Early Diagnosis of Acute Kidney Injury after Cardiac Surgery in Adult Patients. Biomarkers 2013, 18, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susantitaphong, P.; Siribamrungwong, M.; Doi, K.; Noiri, E.; Terrin, N.; Jaber, B.L. Performance of Urinary Liver-Type Fatty Acid–Binding Protein in Acute Kidney Injury: A Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2013, 61, 430–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parikh, C.R.; Thiessen-Philbrook, H.; Garg, A.X.; Kadiyala, D.; Shlipak, M.G.; Koyner, J.L.; Edelstein, C.L.; Devarajan, P.; Patel, U.D.; Zappitelli, M.; et al. Performance of Kidney Injury Molecule-1 and Liver Fatty Acid-Binding Protein and Combined Biomarkers of AKI after Cardiac Surgery. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2013, 8, 1079–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, A.C.M.; Zager, R.A. Mechanisms Underlying Increased TIMP2 and IGFBP7 Urinary Excretion in Experimental AKI. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. JASN 2018, 29, 2157–2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Maclean, W.; Singh, T.; Mackenzie, P.; Rockall, T.; Forni, L.G. A Prospective Diagnostic Study Investigating Urinary Biomarkers of AKI in Major Abdominal Surgery (the AKI-Biomas Study). Crit. Care 2025, 29, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacquaniti, A.; Ceresa, F.; Campo, S.; Barbera, G.; Caruso, D.; Palazzo, E.; Patanè, F.; Monardo, P. Acute Kidney Injury and Sepsis after Cardiac Surgery: The Roles of Tissue Inhibitor Metalloproteinase-2, Insulin-like Growth Factor Binding Protein-7, and Mid-Regional Pro-Adrenomedullin. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 5193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunnerson, K.J.; Shaw, A.D.; Chawla, L.S.; Bihorac, A.; Al-Khafaji, A.; Kashani, K.; Lissauer, M.; Shi, J.; Walker, M.G.; Kellum, J.A. TIMP2•IGFBP7 Biomarker Panel Accurately Predicts Acute Kidney Injury in High-Risk Surgical Patients. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016, 80, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gocze, I.; Koch, M.; Renner, P.; Zeman, F.; Graf, B.M.; Dahlke, M.H.; Nerlich, M.; Schlitt, H.J.; Kellum, J.A.; Bein, T. Urinary Biomarkers TIMP-2 and IGFBP7 Early Predict Acute Kidney Injury after Major Surgery. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0120863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Eynde, J.; Schuermans, A.; Verbakel, J.Y.; Gewillig, M.; Kutty, S.; Allegaert, K.; Mekahli, D. Biomarkers of Acute Kidney Injury after Pediatric Cardiac Surgery: A Meta-Analysis of Diagnostic Test Accuracy. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2022, 181, 1909–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, J.; Li, L.; Tu, H.; Luo, Y.; Cao, Z.; Zhou, K.; Rizvi, S.M.M.; Tie, H.; Jiang, Y. Mechanism and Clinical Role of TIMP-2 and IGFBP-7 in Cardiac Surgery-Associated Acute Kidney Injury: A Review. Medicine 2024, 103, e38124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Ma, Z.; Qu, K.; Liu, S.; Niu, W.; Lin, T. Diagnostic Prediction of Urinary [TIMP-2] x [IGFBP7] for Acute Kidney Injury: A Meta-Analysis Exploring Detection Time and Cutoff Levels. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 100631–100639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monaco, F.; Labanca, R.; Fresilli, S.; Barucco, G.; Licheri, M.; Frau, G.; Osenberg, P.; Belletti, A. Effect of Urine Output on the Predictive Precision of NephroCheck in On-Pump Cardiac Surgery With Crystalloid Cardioplegia: Insights from the PrevAKI Study. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2024, 38, 1689–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moser, B.; Loetscher, P. Lymphocyte Traffic Control by Chemokines. Nat. Immunol. 2001, 2, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlotnik, A.; Yoshie, O. Chemokines. Immunity 2000, 12, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koyner, J.L.; Chawla, L.S.; Bihorac, A.; Gunnerson, K.J.; Schroeder, R.; Demirjian, S.; Hodgson, L.; Frey, J.A.; Wilber, S.T.; Kampf, J.P.; et al. Performance of a Standardized Clinical Assay for Urinary C-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 14 (CCL14) for Persistent Severe Acute Kidney Injury. Kidney360 2022, 3, 1158–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massoth, C.; Küllmar, M.; Enders, D.; Kellum, J.A.; Forni, L.G.; Meersch, M.; Zarbock, A.; Massoth, C.; Küllmar, M.; Weiss, R.; et al. Comparison of C-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 14 with Other Biomarkers for Adverse Kidney Events after Cardiac Surgery. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2023, 165, 199–207.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoste, E.; Bihorac, A.; Al-Khafaji, A.; Ortega, L.M.; Ostermann, M.; Haase, M.; Zacharowski, K.; Wunderink, R.; Heung, M.; Lissauer, M.; et al. Identification and Validation of Biomarkers of Persistent Acute Kidney Injury: The RUBY Study. Intensive Care Med. 2020, 46, 943–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, K.; Jiang, W.; Song, L.; Li, X.; Zhang, C.; Li, L.; Feng, Y.; Yang, J.; Wang, T.; Wang, H.; et al. Persistent Acute Kidney Injury Biomarkers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Chim. Acta 2025, 564, 119907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Pan, H.-C.; Hsu, C.-K.; Sun, C.-Y.; Chen, C.-Y.; Chen, Y.-H.; Hsu, H.-J.; Wu, I.-W.; Wu, V.-C.; Hoste, E. Performance of Urinary C–C Motif Chemokine Ligand 14 for the Prediction of Persistent Acute Kidney Injury: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Crit. Care 2023, 27, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A. CXC Chemokine Family. In Encyclopedia of Respiratory Medicine; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 357–379. ISBN 978-0-08-102724-0. [Google Scholar]

- Moledina, D.G.; Obeid, W.; Smith, R.N.; Rosales, I.; Sise, M.E.; Moeckel, G.; Kashgarian, M.; Kuperman, M.; Campbell, K.N.; Lefferts, S.; et al. Identification and Validation of Urinary CXCL9 as a Biomarker for Diagnosis of Acute Interstitial Nephritis. J. Clin. Investig. 2023, 133, e168950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Duijl, T.T.; De Rooij, E.N.M.; Treep, M.M.; Koelemaij, M.E.; Romijn, F.P.H.T.M.; Hoogeveen, E.K.; Ruhaak, L.R.; Le Cessie, S.; De Fijter, J.W.; Cobbaert, C.M. Urinary Kidney Injury Biomarkers Are Associated with Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury Severity in Kidney Allograft Recipients. Clin. Chem. 2023, 69, 924–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canney, M.; Clark, E.G.; Hiremath, S. Biomarkers in Acute Kidney Injury: On the Cusp of a New Era? J. Clin. Investig. 2023, 133, e171431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Federico, G.; Meister, M.; Mathow, D.; Heine, G.H.; Moldenhauer, G.; Popovic, Z.V.; Nordström, V.; Kopp-Schneider, A.; Hielscher, T.; Nelson, P.J.; et al. Tubular Dickkopf-3 Promotes the Development of Renal Atrophy and Fibrosis. JCI Insight 2016, 1, e84916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schunk, S.J.; Zarbock, A.; Meersch, M.; Küllmar, M.; Kellum, J.A.; Schmit, D.; Wagner, M.; Triem, S.; Wagenpfeil, S.; Gröne, H.-J.; et al. Association between Urinary Dickkopf-3, Acute Kidney Injury, and Subsequent Loss of Kidney Function in Patients Undergoing Cardiac Surgery: An Observational Cohort Study. Lancet 2019, 394, 488–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibert, F.S.; Heringhaus, A.; Pagonas, N.; Rohn, B.; Bauer, F.; Trappe, H.-J.; Landmesser, U.; Babel, N.; Westhoff, T.H. Dickkopf-3 in the Prediction of Contrast Media Induced Acute Kidney Injury. J. Nephrol. 2021, 34, 821–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.H.; Yeo, I.J.; Son, D.J.; Han, S.B.; Yoon, D.Y.; Lee, D.H.; Hong, J.T. Chitinase 3-like Protein 1 Deficiency Ameliorates Drug-Induced Acute Liver Injury by Inhibition of Neutrophil Recruitment through Lipocalin-2. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1548832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Loor, J.; Herck, I.; Francois, K.; Van Wesemael, A.; Nuytinck, L.; Meyer, E.; Hoste, E.A.J. Diagnosis of Cardiac Surgery-Associated Acute Kidney Injury: Differential Roles of Creatinine, Chitinase 3-like Protein 1 and Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin: A Prospective Cohort Study. Ann. Intensive Care 2017, 7, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Loor, J.; Decruyenaere, J.; Demeyere, K.; Nuytinck, L.; Hoste, E.A.J.; Meyer, E. Urinary Chitinase 3-like Protein 1 for Early Diagnosis of Acute Kidney Injury: A Prospective Cohort Study in Adult Critically Ill Patients. Crit. Care 2016, 20, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.K.; Bailly, V.; Abichandani, R.; Thadhani, R.; Bonventre, J.V. Kidney Injury Molecule-1 (KIM-1): A Novel Biomarker for Human Renal Proximal Tubule Injury. Kidney Int. 2002, 62, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, J.; Qiu, Y.; Qin, Z.; Su, B. The Value of Kidney Injury Molecule 1 in Predicting Acute Kidney Injury in Adult Patients: A Systematic Review and Bayesian Meta-Analysis. J. Transl. Med. 2021, 19, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westhoff, J.H.; Seibert, F.S.; Waldherr, S.; Bauer, F.; Tönshoff, B.; Fichtner, A.; Westhoff, T.H. Urinary Calprotectin, Kidney Injury Molecule-1, and Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin for the Prediction of Adverse Outcome in Pediatric Acute Kidney Injury. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2017, 176, 745–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Huang, Y.; Shang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xu, G. The Predictive Value of Urinary Kidney Injury Molecular 1 for the Diagnosis of Contrast-Induced Acute Kidney Injury after Cardiac Catheterization: A Meta-Analysis. J. Interv. Cardiol. 2020, 2020, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasquez-Rios, G.; Moledina, D.G.; Jia, Y.; McArthur, E.; Mansour, S.G.; Thiessen-Philbrook, H.; Shlipak, M.G.; Koyner, J.L.; Garg, A.X.; Parikh, C.R.; et al. Pre-Operative Kidney Biomarkers and Risks for Death, Cardiovascular and Chronic Kidney Disease Events after Cardiac Surgery: The TRIBE-AKI Study. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2022, 17, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, J.S.C.; Saleem, M.; Florkowski, C.M.; George, P.M. Cystatin C--a Paradigm of Evidence Based Laboratory Medicine. Clin. Biochem. Rev. 2008, 29, 47–62. [Google Scholar]

- Herget-Rosenthal, S.; Van Wijk, J.A.E.; Bröcker-Preuss, M.; Bökenkamp, A. Increased Urinary Cystatin C Reflects Structural and Functional Renal Tubular Impairment Independent of Glomerular Filtration Rate. Clin. Biochem. 2007, 40, 946–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makinde, R.A.; Alaje, A.K.; Ajose, A.O.; Adedeji, T.A.; Onakpoya, U.U. Cardiac Surgery-Associated Acute Kidney Injury (CSA-AKI) in Children with Congenital Heart Diseases in Southwest Nigeria. Ann. Card. Anaesth. 2025, 28, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Lin, X.; Xie, B.; Huang, R.; Yan, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhu, M.; Lu, R.; Qian, J.; Ni, Z.; et al. Early Serum Cystatin C-Enhanced Risk Prediction for Acute Kidney Injury Post Cardiac Surgery: A Prospective, Observational, Cohort Study. Biomarkers 2020, 25, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zakaria, M.; Hassan, T.; Refaat, A.; Fathy, M.; Hashem, M.I.A.; Khalifa, N.; Ali, A.A.; Elhewala, A.; Ramadan, A.; Nafea, A. Role of Serum Cystatin C in the Prediction of Acute Kidney Injury Following Pediatric Cardiac Surgeries: A Single Center Experience. Medicine 2022, 101, e31938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, P.; Fu, X.C.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, X.; Bian, L.; Zhati, N.; Zhang, S.; Wei, W. The Value of Serum Cystatin c in Predicting Acute Kidney Injury after Cardiac Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0310049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, H.; Liu, X.; Yang, D.; Zhang, D.; Wang, L.; Hu, L. Comparing Diagnostic Accuracy of Biomarkers for Acute Kidney Injury after Major Surgery: A PRISMA Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Medicine 2023, 102, e35284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spahillari, A.; Parikh, C.R.; Sint, K.; Koyner, J.L.; Patel, U.D.; Edelstein, C.L.; Passik, C.S.; Thiessen-Philbrook, H.; Swaminathan, M.; Shlipak, M.G.; et al. Serum Cystatin C- versus Creatinine-Based Definitions of Acute Kidney Injury Following Cardiac Surgery: A Prospective Cohort Study. Am. J. Kidney Dis. Off. J. Natl. Kidney Found. 2012, 60, 922–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bökenkamp, A.; van Wijk, J.A.E.; Lentze, M.J.; Stoffel-Wagner, B. Effect of Corticosteroid Therapy on Serum Cystatin C and Beta2-Microglobulin Concentrations. Clin. Chem. 2002, 48, 1123–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fricker, M.; Wiesli, P.; Brändle, M.; Schwegler, B.; Schmid, C. Impact of Thyroid Dysfunction on Serum Cystatin C. Kidney Int. 2003, 63, 1944–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xin, C.; Xie, J.; Fan, H.; Sun, X.; Shi, B. Association Between Serum Cystatin C and Thyroid Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 766516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, L.A.; Schmid, C.H.; Greene, T.; Li, L.; Beck, G.J.; Joffe, M.M.; Froissart, M.; Kusek, J.W.; Zhang, Y.; Coresh, J.; et al. Factors Other than Glomerular Filtration Rate Affect Serum Cystatin C Levels. Kidney Int. 2009, 75, 652–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, C.A.; Rule, A.D.; Collier, C.P.; Akbari, A.; Lieske, J.C.; Lepage, N.; Doucette, S.; Knoll, G.A. The Impact of Interlaboratory Differences in Cystatin C Assay Measurement on Glomerular Filtration Rate Estimation. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. CJASN 2011, 6, 2150–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, T.M.; Bird, C.A.; Broyles, D.L.; Klause, U. Determination of Urinary Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin (uNGAL) Reference Intervals in Healthy Adult and Pediatric Individuals Using a Particle-Enhanced Turbidimetric Immunoassay. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sladen, R.N. Perioperative Acute Renal Injury: Revisiting Pathophysiology. Anesthesiology 2024, 141, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, M.; Dent, C.L.; Ma, Q.; Dastrala, S.; Grenier, F.; Workman, R.; Syed, H.; Ali, S.; Barasch, J.; Devarajan, P. Urine NGAL Predicts Severity of Acute Kidney Injury after Cardiac Surgery: A Prospective Study. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. CJASN 2008, 3, 665–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Chen, S.; Ge, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Li, C.; Qiao, Z.; Hu, H.; Zhu, J. Relationship between Perioperative Plasma Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin Level and Acute Kidney Injury after Acute Type A Aortic Dissection. J. Thorac. Dis. 2025, 17, 2126–2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, C.; de Paiva Haddad, L.B.; de Melo, P.D.V.; Malbouisson, L.M.; do Carmo, L.P.F.; D’Albuquerque, L.A.C.; Macedo, E. Early Detection of Acute Kidney Injury in the Perioperative Period of Liver Transplant with Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin. BMC Nephrol. 2019, 20, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Introcaso, G.; Nafi, M.; Bonomi, A.; L’Acqua, C.; Salvi, L.; Ceriani, R.; Carcione, D.; Cattaneo, A.; Sandri, M.T. Improvement of Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin Sensitivity and Specificity by Two Plasma Measurements in Predicting Acute Kidney Injury after Cardiac Surgery. Biochem. Medica 2018, 28, 030701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, T.E.; Muehlschlegel, J.D.; Liu, K.-Y.; Fox, A.A.; Collard, C.D.; Shernan, S.K.; Body, S.C. CABG Genomics Investigators. Plasma Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin and Acute Postoperative Kidney Injury in Adult Cardiac Surgical Patients. Anesth. Analg. 2010, 110, 1541–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dent, C.L.; Ma, Q.; Dastrala, S.; Bennett, M.; Mitsnefes, M.M.; Barasch, J.; Devarajan, P. Plasma Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin Predicts Acute Kidney Injury, Morbidity and Mortality after Pediatric Cardiac Surgery: A Prospective Uncontrolled Cohort Study. Crit. Care 2007, 11, R127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachorzewska-Gajewska, H.; Tomaszuk-Kazberuk, A.; Jarocka, I.; Mlodawska, E.; Lopatowska, P.; Zalewska-Adamiec, M.; Dobrzycki, S.; Musial, W.J.; Malyszko, J. Does Neutrophil Gelatinase-Asociated Lipocalin Have Prognostic Value in Patients with Stable Angina Undergoing Elective PCI? A 3-Year Follow-up Study. Kidney Blood Press. Res. 2013, 37, 280–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mårtensson, J.; Bellomo, R. The Rise and Fall of NGAL in Acute Kidney Injury. Blood Purif. 2014, 37, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terzi, I.; Papaioannou, V.; Papanas, N.; Dragoumanis, C.; Petala, A.; Theodorou, V.; Gioka, T.; Vargemezis, V.; Maltezos, E.; Pneumatikos, I. Alpha1-Microglobulin as an Early Biomarker of Sepsis-Associated Acute Kidney Injury: A Prospective Cohort Study. Hippokratia 2014, 18, 262–268. [Google Scholar]

- Amatruda, J.G.; Estrella, M.M.; Garg, A.X.; Thiessen-Philbrook, H.; McArthur, E.; Coca, S.G.; Parikh, C.R.; Shlipak, M.G.; for the TRIBE-AKI Consortium. Urine Alpha-1-Microglobulin Levels and Acute Kidney Injury, Mortality, and Cardiovascular Events Following Cardiac Surgery. Am. J. Nephrol. 2021, 52, 673–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burmakin, M.; Gilmour, P.S.; Gram, M.; Shushakova, N.; Sandoval, R.M.; Molitoris, B.A.; Larsson, T.E. Therapeutic α-1-Microglobulin Ameliorates Kidney Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Am. J. Physiol.-Ren. Physiol. 2024, 327, F103–F112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, R.; Meersch, M.; Wempe, C.; Von Groote, T.; Agervald, T.; Zarbock, A. Recombinant Alpha-1-Microglobulin (RMC-035) to Prevent Acute Kidney Injury in Cardiac Surgery Patients: Phase 1b Evaluation of Safety and Pharmacokinetics. Kidney Int. Rep. 2023, 8, 980–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcello, M.; Schöne, L.M.; Booke, H.; Hognon-Bąk, K.; Zarbock, A. Recombinant Alpha-1 Microglobulin to Improve Outcomes in Survivors of AKI. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2025, gfaf194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malyszko, J.; Bachorzewska-Gajewska, H.; Malyszko, J.S.; Koc-Zorawska, E.; Matuszkiewicz-Rowinska, J.; Dobrzycki, S. Hepcidin—Potential Biomarker of Contrast-Induced Acute Kidney Injury in Patients Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Interventions. Adv. Med. Sci. 2019, 64, 211–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, N.; Rigatto, C.; Zappitelli, M.; Gao, A.; Christie, S.; Hiebert, B.; Arora, R.C.; Ho, J. Urinary Hepcidin-25 Is Elevated in Patients That Avoid Acute Kidney Injury Following Cardiac Surgery. Can. J. Kidney Health Dis. 2018, 5, 2054358117744224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prowle, J.R.; Westerman, M.; Bellomo, R. Urinary Hepcidin: An Inverse Biomarker of Acute Kidney Injury after Cardiopulmonary Bypass? Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 2010, 16, 540–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haase-Fieiltz, A.; Mertens, P.; Plaß, M.; Westerman, M.; Bellomo, R.; Haase, M. Low Preoperative Hepcidin Concentration Is a Risk Factor for Mortality but Not for Acute Kidney Injury after Cardiac Surgery. Crit. Care 2012, 16, P402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, C.; Haase, M.; Albert, A.; Ernst, M.; Kropf, S.; Bellomo, R.; Westphal, S.; Braun-Dullaeus, R.C.; Haase-Fielitz, A.; Elitok, S. Predictive Value of Plasma NGAL:Hepcidin-25 for Major Adverse Kidney Events After Cardiac Surgery with Cardiopulmonary Bypass: A Pilot Study. Ann. Lab. Med. 2021, 41, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javid, M.; Mirdamadi, A.; Javid, M.; Amini-Salehi, E.; Vakilpour, A.; Keivanlou, M.-H.; Porteghali, P.; Hassanipour, S. Gamma Glutamyl Transferase as a Biomarker to Predict Contrast-Induced Nephropathy among Patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome Undergoing Coronary Interventions: A Meta-Analysis. Ann. Med. Surg. 2023, 85, 4033–4040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, K.-H.; Wang, C.-H.; Wu, C.-H.; Huang, T.-M.; Wu, P.-C.; Lai, C.-H.; Tseng, L.-J.; Tsai, P.-R.; Connolly, R.; Wu, V.-C. Urinary π-Glutathione S-Transferase Predicts Advanced Acute Kidney Injury Following Cardiovascular Surgery. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 26335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyner, J.L.; Vaidya, V.S.; Bennett, M.R.; Ma, Q.; Worcester, E.; Akhter, S.A.; Raman, J.; Jeevanandam, V.; O’Connor, M.F.; Devarajan, P.; et al. Urinary Biomarkers in the Clinical Prognosis and Early Detection of Acute Kidney Injury. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2010, 5, 2154–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moledina, D.G.; Wilson, F.P.; Pober, J.S.; Perazella, M.A.; Singh, N.; Luciano, R.L.; Obeid, W.; Lin, H.; Kuperman, M.; Moeckel, G.W.; et al. Urine TNF-α and IL-9 for Clinical Diagnosis of Acute Interstitial Nephritis. JCI Insight 2019, 4, e127456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adisurya, G.; Abba, K.A.; Rehatta, N.M.; Hardiono, H. Plasma Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin and Interleukin-9 as Acute Kidney Injury Predictors After Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Following Cardiopulmonary Bypass. Int. J. Sci. Adv. 2021, 2, 591–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xu, K.; Xiang, Y.; Ma, B.; Li, H.; Li, Y.; Shi, Y.; Li, S.; Bai, Y. Role of MCP-1 as an Inflammatory Biomarker in Nephropathy. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1303076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, Y.; Xu, L.; Melchinger, I.; Thiessen-Philbrook, H.; Moledina, D.G.; Coca, S.G.; Hsu, C.-Y.; Go, A.S.; Liu, K.D.; Siew, E.D.; et al. Longitudinal Biomarkers and Kidney Disease Progression after Acute Kidney Injury. JCI Insight 2023, 8, e167731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moledina, D.G.; Isguven, S.; McArthur, E.; Thiessen-Philbrook, H.; Garg, A.X.; Shlipak, M.; Whitlock, R.; Kavsak, P.A.; Coca, S.G.; Parikh, C.R.; et al. Plasma Monocyte Chemotactic Protein-1 Is Associated with Acute Kidney Injury and Death After Cardiac Operations. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2017, 104, 613–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menez, S.; Ju, W.; Menon, R.; Moledina, D.G.; Thiessen Philbrook, H.; McArthur, E.; Jia, Y.; Obeid, W.; Mansour, S.G.; Koyner, J.L.; et al. Urinary EGF and MCP-1 and Risk of CKD after Cardiac Surgery. JCI Insight 2021, 6, e147464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leszczyńska, B.; Buczyński, M.; Deja, A.; Daniel, M.; Zawadzki, M.; Szymańska-Beta, K.; Stelmaszczyk-Emmel, A.; Gaj, M.; Pańczyk-Tomaszewska, M. The Usefulness of Urinary Netrin-1 Determination as an Early Marker of Acute Kidney Injury in Children after Cardiac Surgery. Arch. Med. Sci. AMS 2025, 21, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, G.; Krawczeski, C.D.; Woo, J.G.; Wang, Y.; Devarajan, P. Urinary Netrin-1 Is an Early Predictive Biomarker of Acute Kidney Injury after Cardiac Surgery. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. CJASN 2010, 5, 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowska, L.; Matuszkiewicz-Rowińska, J.; Jayakumar, C.; Oldakowska-Jedynak, U.; Looney, S.; Galas, M.; Dutkiewicz, M.; Krawczyk, M.; Ramesh, G. Netrin-1 and Semaphorin 3A Predict the Development of Acute Kidney Injury in Liver Transplant Patients. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e107898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranganathan, P.; Jayakumar, C.; Mohamed, R.; Weintraub, N.L.; Ramesh, G. Semaphorin 3A Inactivation Suppresses Ischemia-Reperfusion-Induced Inflammation and Acute Kidney Injury. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2014, 307, F183–F194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ning, L.; Li, Z.; Wei, D.; Chen, H.; Yang, C.; Wu, D.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J. Urinary Semaphorin 3A as an Early Biomarker to Predict Contrast-Induced Acute Kidney Injury in Patients Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2018, 51, e6487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayakumar, C.; Ranganathan, P.; Devarajan, P.; Krawczeski, C.D.; Looney, S.; Ramesh, G. Semaphorin 3A Is a New Early Diagnostic Biomarker of Experimental and Pediatric Acute Kidney Injury. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e58446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Li, Y.; Scherer, N.; Grundner-Culemann, F.; Lehtimäki, T.; Mishra, B.H.; Raitakari, O.T.; Nauck, M.; Eckardt, K.-U.; Sekula, P.; et al. Genetics of Osteopontin in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease: The German Chronic Kidney Disease Study. PLoS Genet. 2022, 18, e1010139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weerasinghe Mudiyanselage, P.D.E.; Ning, L.; Ojha, R.; Komaru, Y.; Kefalogianni, E.; Friess, S.; Celorrio Navarro, M.; Herrlich, A. Neuroinflammation and Neurological Dysfunction After AKI Is Driven by Kidney-Released Osteopontin and Not Uremia: TH-OR009. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2025, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamissi, F.Z.; Ning, L.; Kefaloyianni, E.; Dun, H.; Arthanarisami, A.; Keller, A.; Atkinson, J.J.; Li, W.; Wong, B.; Dietmann, S.; et al. Identification of Kidney Injury–Released Circulating Osteopontin as Causal Agent of Respiratory Failure. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabm5900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekiguchi, K.; Matsuda, A.; Yamada, M.; Matsumoto, S.; Sakurazawa, N.; Kawano, Y.; Yamada, T.; Miyashita, M.; Yoshida, H. The Utility of Serum Osteopontin Levels for Predicting Postoperative Complications after Colorectal Cancer Surgery. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 27, 1706–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohebi, R.; Van Kimmenade, R.; McCarthy, C.; Gaggin, H.; Mehran, R.; Dangas, G.; Januzzi, J.L. A Biomarker-Enhanced Model for Prediction of Acute Kidney Injury and Cardiovascular Risk Following Angiographic Procedures: CASABLANCA AKI Prediction Substudy. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2022, 11, e025729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oyaert, M.; Delanghe, J.; Brouwers, A.; Bové, T.; Schaubroeck, H.; Delrue, C.; Vandenberghe, W.; Speeckaert, M.; Hoste, E. Renal Tubular Epithelial Cells as an Easily Accessible Biomarker for Diagnosing AKI Post Cardiac Surgery. Intensive Care Med. 2025, 51, 870–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostermann, M.; Darmon, M.; Joannidis, M. Renal Tubular Epithelial Cells: A Revived Kidney Biomarker? Intensive Care Med. 2025, 51, 1348–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Geus, H.R.H.; Fortrie, G.; Betjes, M.G.H.; van Schaik, R.H.N.; Groeneveld, A.B.J. Time of Injury Affects Urinary Biomarker Predictive Values for Acute Kidney Injury in Critically Ill, Non-Septic Patients. BMC Nephrol. 2013, 14, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Duijl, T.T.; Soonawala, D.; de Fijter, J.W.; Ruhaak, L.R.; Cobbaert, C.M. Rational Selection of a Biomarker Panel Targeting Unmet Clinical Needs in Kidney Injury. Clin. Proteom. 2021, 18, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayaraman, R.; Sunder, S.; Sathi, S.; Gupta, V.K.; Sharma, N.; Kanchi, P.; Gupta, A.; Daksh, S.K.; Ram, P.; Mohamed, A. Post Cardiac Surgery Acute Kidney Injury: A Woebegone Status Rejuvenated by the Novel Biomarkers. Nephro-Urol. Mon. 2014, 6, e19598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, R.K.; Wong, H.R.; Krawczeski, C.D.; Wheeler, D.S.; Manning, P.B.; Chawla, L.S.; Devarajan, P.; Goldstein, S.L. Combining Functional and Tubular Damage Biomarkers Improves Diagnostic Precision for Acute Kidney Injury after Cardiac Surgery. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014, 64, 2753–2762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzzi, L.M.; Bergler, T.; Binnall, B.; Engelman, D.T.; Forni, L.; Germain, M.J.; Gluck, E.; Göcze, I.; Joannidis, M.; Koyner, J.L.; et al. Clinical Use of [TIMP-2]•[IGFBP7] Biomarker Testing to Assess Risk of Acute Kidney Injury in Critical Care: Guidance from an Expert Panel. Crit. Care 2019, 23, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Nynatten, L.R.; Miller, M.R.; Patel, M.A.; Daley, M.; Filler, G.; Badrnya, S.; Miholits, M.; Webb, B.; McIntyre, C.W.; Fraser, D.D. A Novel Multiplex Biomarker Panel for Profiling Human Acute and Chronic Kidney Disease. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 21210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food and Drug Administration; Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). Reviews: Qualification of Biomarker: Clusterin (CLU), Cystatin-C (CysC), Kidney Injury Molecule-1 (KIM-1), N-Acetyl-Beta-D-Glucosaminidase (NAG), Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin (NGAL), and Osteopontin (OPN); FDA: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2024.

- Griffin, B.R.; Gist, K.M.; Faubel, S. Current Status of Novel Biomarkers for the Diagnosis of Acute Kidney Injury: A Historical Perspective. J. Intensive Care Med. 2020, 35, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- bioMérieux Receives FDA Clearance for NEPHROCHECK® Test on VIDAS®. Available online: https://www.biomerieux.com/corp/en/journalists/press-releases/biomerieux-receives-fda-clearance-for-nephrocheck--test-on-vidas.html (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- SphingoTec’s Innovative IVD Product Sphingotest® penKid® Receives First IVDR Certificate. Available online: https://www.sphingotec.eu/sphingotec-s-innovative-ivd-product-sphingotest-penkid-receives-first-ivdr-certificate (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- See, C.Y.; Pan, H.-C.; Chen, J.-Y.; Wu, C.-Y.; Liao, H.-W.; Huang, Y.-T.; Liu, J.-H.; Wu, V.-C.; Ostermann, M. Improvement of Composite Kidney Outcomes by AKI Care Bundles: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Crit. Care 2023, 27, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarbock, A.; Küllmar, M.; Ostermann, M.; Lucchese, G.; Baig, K.; Cennamo, A.; Rajani, R.; McCorkell, S.; Arndt, C.; Wulf, H.; et al. Prevention of Cardiac Surgery-Associated Acute Kidney Injury by Implementing the KDIGO Guidelines in High-Risk Patients Identified by Biomarkers: The PrevAKI-Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial. Anesth. Analg. 2021, 133, 292–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meersch, M.; Schmidt, C.; Hoffmeier, A.; Van Aken, H.; Wempe, C.; Gerss, J.; Zarbock, A. Prevention of Cardiac Surgery-Associated AKI by Implementing the KDIGO Guidelines in High Risk Patients Identified by Biomarkers: The PrevAKI Randomized Controlled Trial. Intensive Care Med. 2017, 43, 1551–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göcze, I.; Jauch, D.; Götz, M.; Kennedy, P.; Jung, B.; Zeman, F.; Gnewuch, C.; Graf, B.M.; Gnann, W.; Banas, B.; et al. Biomarker-Guided Intervention to Prevent Acute Kidney Injury After Major Surgery: The Prospective Randomized BigpAK Study. Ann. Surg. 2018, 267, 1013–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Groote, T.; Meersch, M.; Romagnoli, S.; Ostermann, M.; Ripollés-Melchor, J.; Schneider, A.G.; Vandenberghe, W.; Monard, C.; De Rosa, S.; Cattin, L.; et al. Biomarker-Guided Intervention to Prevent Acute Kidney Injury after Major Surgery (BigpAK-2 Trial): Study Protocol for an International, Prospective, Randomised Controlled Multicentre Trial. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e070240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Groote, T.; Danzer, M.F.; Meersch, M.; Zarbock, A.; Gerß, J. BigpAK-2 study group Statistical Analysis Plan for the Biomarker-Guided Intervention to Prevent Acute Kidney Injury after Major Surgery (BigpAK-2) Study: An International Randomised Controlled Multicentre Trial. Crit. Care Resusc. J. Australas. Acad. Crit. Care Med. 2024, 26, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaubroeck, H.A.I.; Vargas, D.; Vandenberghe, W.; Hoste, E.A.J. Impact of AKI Care Bundles on Kidney and Patient Outcomes in Hospitalized Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Nephrol. 2021, 22, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasquez-Rios, G.; Oh, W.; Lee, S.; Bhatraju, P.; Mansour, S.G.; Moledina, D.G.; Gulamali, F.F.; Siew, E.D.; Garg, A.X.; Sarder, P.; et al. Joint Modeling of Clinical and Biomarker Data in Acute Kidney Injury Defines Unique Subphenotypes with Differing Outcomes. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2023, 18, 716–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.H.; Zeng, J.T.; Su, X.T.; Zheng, Z. Biomarker-Based Clinical Subphenotypes of Cardiac Surgery Associated Acute Kidney Injury and Their Association with in-Hospital Treatments and Outcomes: A Data-Driven Cluster Analysis. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, ehad655.2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, E.; Sawhney, S.; Brazzelli, M.; Aucott, L.; Scotland, G.; Aceves-Martins, M.; Robertson, C.; Imamura, M.; Poobalan, A.; Manson, P.; et al. Cost-Effectiveness and Value of Information Analysis of NephroCheck and NGAL Tests Compared to Standard Care for the Diagnosis of Acute Kidney Injury. BMC Nephrol. 2021, 22, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brazzelli, M.; Aucott, L.; Aceves-Martins, M.; Robertson, C.; Jacobsen, E.; Imamura, M.; Poobalan, A.; Manson, P.; Scotland, G.; Kaye, C.; et al. Biomarkers for Assessing Acute Kidney Injury for People Who Are Being Considered for Admission to Critical Care: A Systematic Review and Cost-Effectiveness Analysis. Health Technol. Assess. 2022, 26, 1–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| AKI Stage | Serum Creatinine | Urine Output |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.5–1.9 times baseline (7 days) OR ≥0.3 mg/dL increase within 48 h | <0.5 mL/kg/h for 6–12 h |

| 2 | 2.0–2.9 times baseline | <0.5 mL/kg/hour for ≥12 h |

| 3 | 3.0 times baseline OR increase to ≥4.0 mg/dL OR initiation of RRT 1 OR decrease in eGFR 2 to <35 mL/min/1.73 m2 in patients < 18 years | <0.3 mL/kg/hour for ≥24 h OR anuric for ≥12 h |

| Parameter | Limitations |

|---|---|

| Serum Creatinine | Low sensitivity for early AKI, requires ~50% loss of renal function before detectable elevation. Delayed rise 24–48 h after acute insult. Poor discrimination between acute and chronic changes. Volume status affects hemoconcentration. Pregnancy-related decrease during gestation. Muscle mass dependent varies with age, sex, body composition, and nutritional status. Influenced by nonrenal factors including dietary creatine, hepatic function, and metabolic rate. Medication interference with tubular secretion inhibitors falsely elevates levels. Non-specific for injury type including glomerular versus tubular. Inadequate for real-time monitoring. Unreliable in extreme body compositions. |

| Urine Output | Transient oliguria occurs with dehydration, stress, or volume depletion. Prone to collection errors even with urinary catheters (incomplete collection, spillage, miscalculation). Reduced output may reflect prerenal factors rather than intrinsic renal damage. Requires accurate hourly measurement and weight-based calculations. Normal or high urine output can occur despite significant renal dysfunction in non-oliguric injury. Requires sustained reduction over hours to meet diagnostic criteria. Influenced by fluid balance, medications, and hemodynamic status. |

| Biomarker | Name | Sample | Detection Window | Cutoff Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PENK | Proenkephalin A 119–159 | Serum | 2–6 h | ~57.3 pmol/L |

| IL-18 | Interleukin-18 | Urine | 4 h | 1477 pg/mg creatinine |

| L-FABP | Liver-Type Fatty Acid–Binding Protein | Urine | 4–6 h | ~673.1 μg/g creatinine |

| TIMP-2*IGFBP-7 | Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinase-2 * Insulin-Like Growth Factor-Binding Protein-7 | Urine | 4–12 h | >0.3 (ng/mL)2/1000 |

| CCL-14 | C-C Motif Chemokine Ligand-14 | Urine | 6–24 h | 1.3 ng/mL |

| CXCL-9 | C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand-9 | Urine | Postprocedural | N/S |

| DKK-3 | Dickkopf-related Protein-3 | Urine | Preprocedural | >471 pg/mg creatinine |

| CHI3L-1 | Chitinase 3-like Protein-1 | Urine | Postprocedural | ≥5 ng/mL |

| KIM-1 | Kidney Injury Molecule-1 | Urine | 12–24 h | 19 ng/mL |

| CysC | Cystatin C | Urine, Serum | 6–24 h | >1.33 mg/L (peds) ≥25% increase (adults) |

| NGAL | Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin | Urine, Serum | 2–6 h | ~150–154 ng/mL |

| α1m | Alpha-1-Microglobulin | Urine | Preprocedural | N/S |

| Hepcidin-25 | Hepcidin-25 | Urine, Serum | 6–24 h | N/S |

| GGT | Gamma-Glutamyltransferase | Urine | Postprocedural | N/S |

| π-GST | π-Glutathione S-Transferase | Urine | 3–12 h | 16.5 μg/L |

| IL-9 | Interleukin-9 | Urine | Postprocedural | N/S |

| MCP-1 | Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1 | Urine | Post-AKI | N/S |

| NTN-1 | Netrin-1 | Urine | 2–6 h | ~898–2462 pg/mg creatinine |

| SEMA-3A | Semaphorin-3A | Urine | 2–6 h | ~390–848 pg/mg creatinine |

| OPN | Osteopontin | Serum | Postprocedural | N/S |

| RTECs | Renal Tubular Epithelial Cells | Urine | 12–24 h | N/S |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zuzda, K.; Walczak-Wieteska, P.; Andruszkiewicz, P.; Małyszko, J. Acute Kidney Injury Biomarkers in Perioperative Care: A Scoping Review of Clinical Implementation. Diagnostics 2026, 16, 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010094

Zuzda K, Walczak-Wieteska P, Andruszkiewicz P, Małyszko J. Acute Kidney Injury Biomarkers in Perioperative Care: A Scoping Review of Clinical Implementation. Diagnostics. 2026; 16(1):94. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010094

Chicago/Turabian StyleZuzda, Konrad, Paulina Walczak-Wieteska, Paweł Andruszkiewicz, and Jolanta Małyszko. 2026. "Acute Kidney Injury Biomarkers in Perioperative Care: A Scoping Review of Clinical Implementation" Diagnostics 16, no. 1: 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010094

APA StyleZuzda, K., Walczak-Wieteska, P., Andruszkiewicz, P., & Małyszko, J. (2026). Acute Kidney Injury Biomarkers in Perioperative Care: A Scoping Review of Clinical Implementation. Diagnostics, 16(1), 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010094