Heart Failure in Lebanon: A Glimpse into the Reality of Growing Burden

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Patient Selection, and Data Collection

2.2. Statistical Analysis

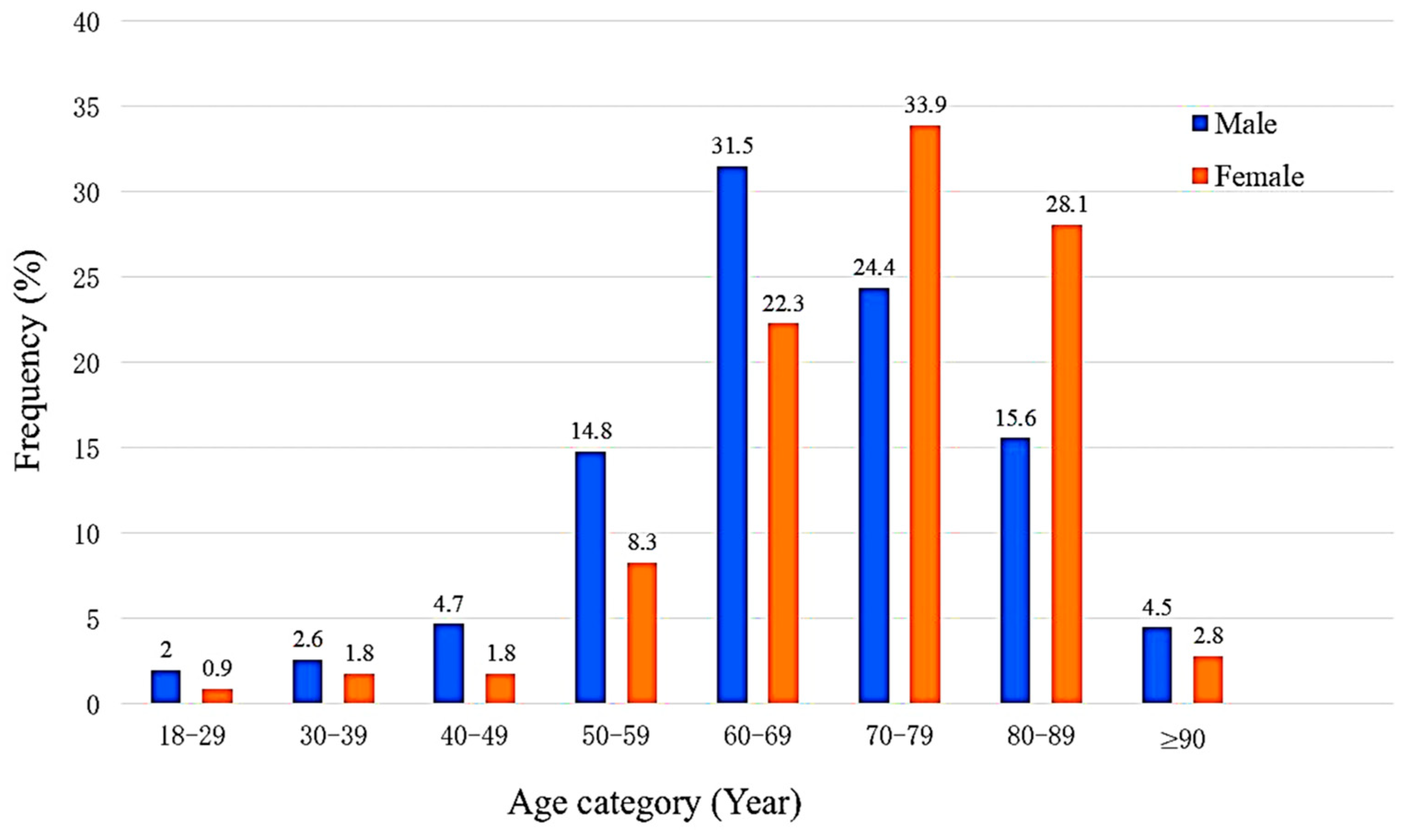

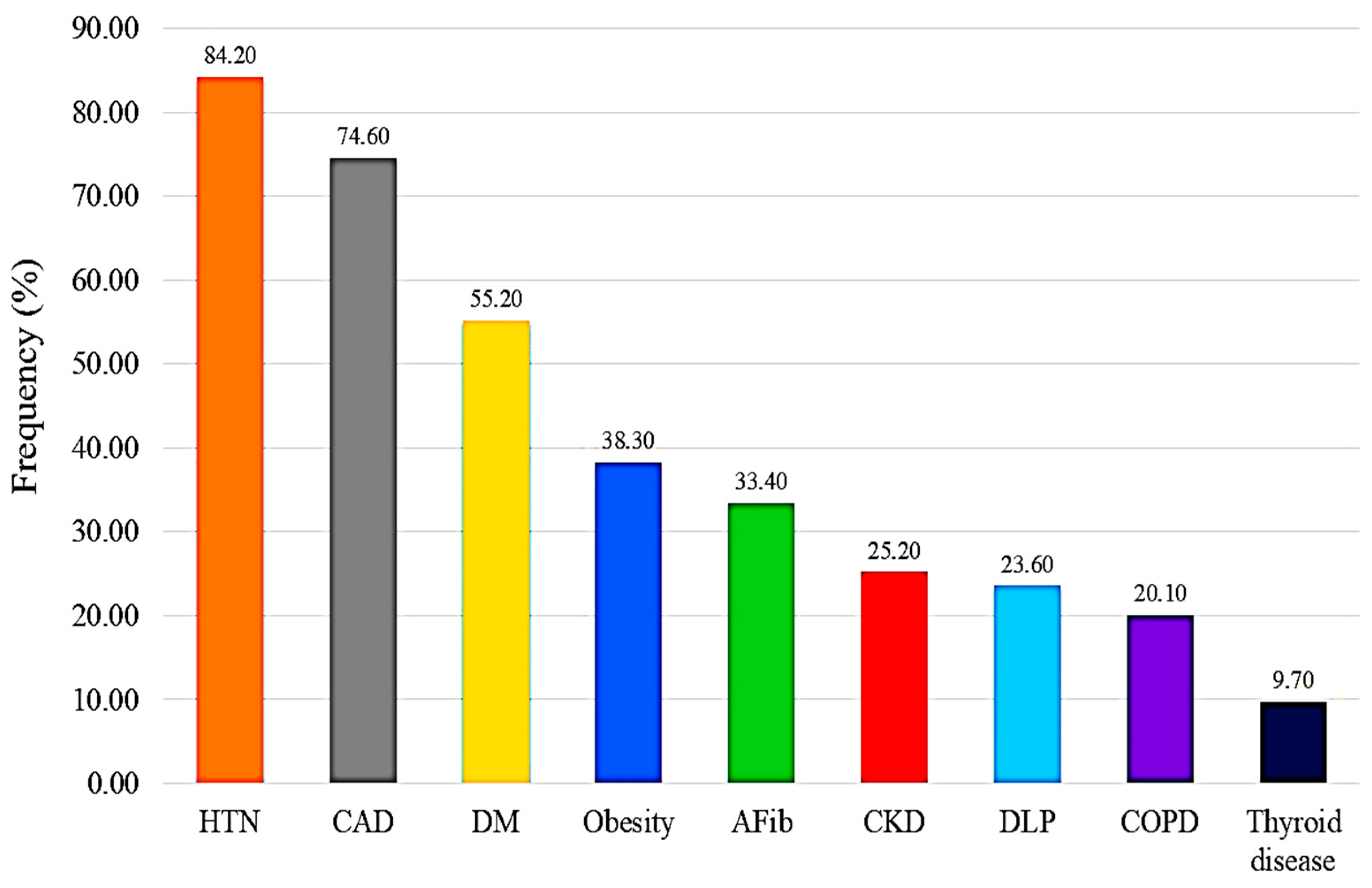

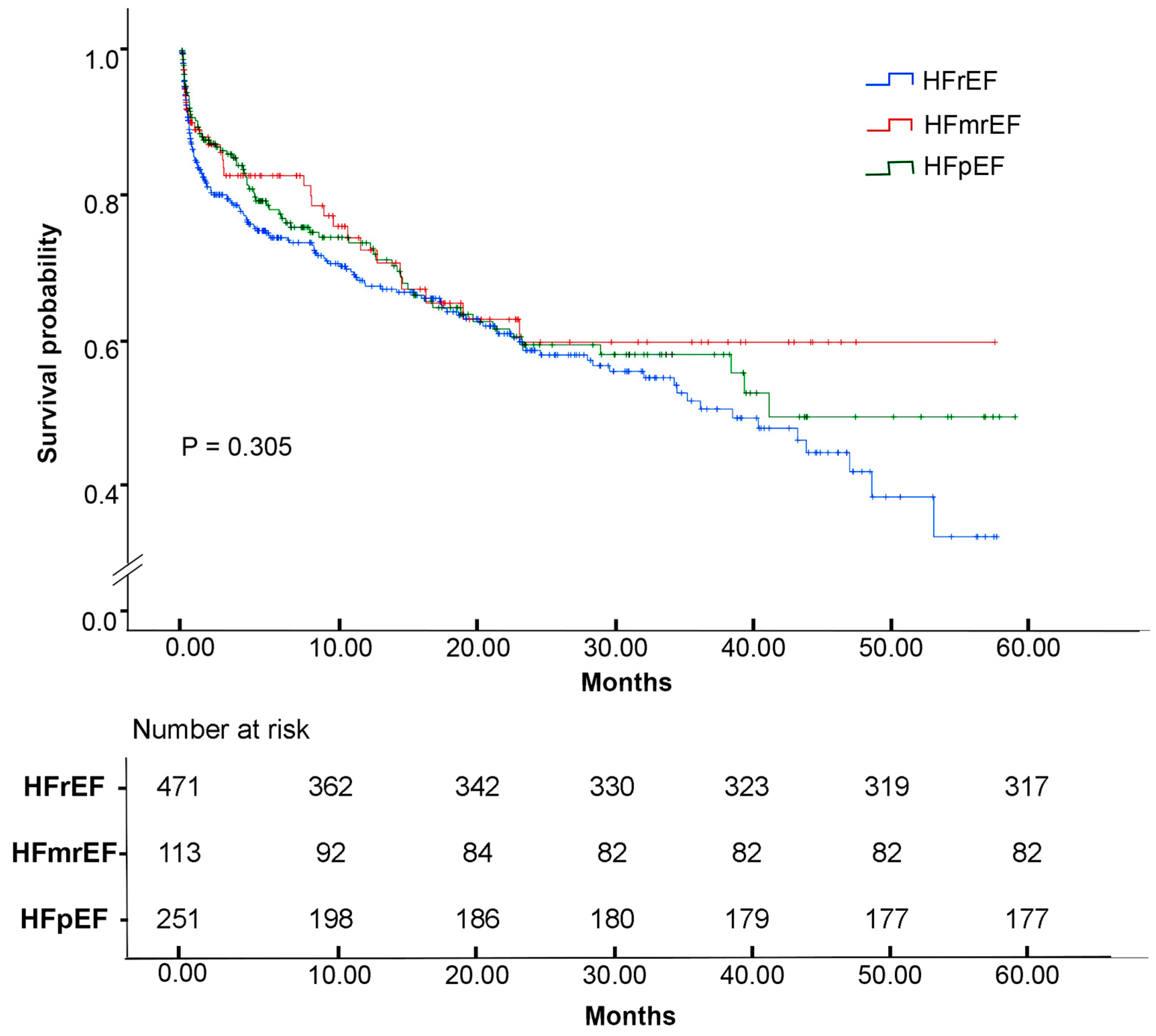

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AAD | Antiarrhythmic drugs |

| ACEi | Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor |

| AFib | Atrial fibrillation |

| ARB | Angiotensin receptor blocker |

| ARNI | Angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| BNP | Brain natriuretic peptide |

| CAD | Coronary artery disease |

| CKD | Chronic kidney disease |

| COPD | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| DM | Diabetes mellitus |

| EF | Ejection fraction |

| eGFR | Estimated glomerular filtration rate |

| HF | Heart failure |

| HFmrEF | Heart failure with mildly reduced ejection fraction |

| HFpEF | Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction |

| HFrEF | Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction |

| HR | Heart rate |

| HTN | Hypertension |

| MRA | Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist |

| TSH | Thyroid-stimulating hormone |

| SGLT2i | Sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitor |

References

- Feng, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J. Epidemiology and Burden of Heart Failure in Asia. JACC Asia 2024, 4, 249–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, B.; Ahmad, T.; Alexander, K.; Baker, W.L.; Bosak, K.; Breathett, K.; Carter, S.; Drazner, M.H.; Dunlay, S.M.; Fonarow, G.C.; et al. HF STATS 2024: Heart Failure Epidemiology and Outcomes Statistics An Updated 2024 Report from the Heart Failure Society of America. J. Card. Fail. 2025, 31, 66–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, C.W.; Aday, A.W.; Almarzooq, Z.I.; Anderson, C.A.M.; Arora, P.; Avery, C.L.; Baker-Smith, C.M.; Beaton, A.Z.; Boehme, A.K.; Buxton, A.E.; et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2023 Update: A Report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2023, 147, e93–e621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, T.; Zhu, S.; Yin, X.; Xie, C.; Xue, J.; Zhu, M.; Weng, F.; Zhu, S.; Xiang, B.; Zhou, X.; et al. Burden, Trends, and Inequalities of Heart Failure Globally, 1990 to 2019: A Secondary Analysis Based on the Global Burden of Disease 2019 Study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2023, 12, e027852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Cesare, M.; Perel, P.; Taylor, S.; Kabudula, C.; Bixby, H.; Gaziano, T.A.; McGhie, D.V.; Mwangi, J.; Pervan, B.; Narula, J.; et al. The Heart of the World. Glob. Heart 2024, 19, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, M.A.; Shah, A.M.; Borlaug, B.A. Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction In Perspective. Circ. Res. 2019, 124, 1598–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, N.; Shah, A.M.; Blaha, M.J.; Chang, P.P.; Rosamond, W.D.; Matsushita, K. Cigarette Smoking, Cessation, and Risk of Heart Failure with Preserved and Reduced Ejection Fraction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2022, 79, 2298–2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Son, Y.J.; Lee, H.J. Association between persistent smoking after a diagnosis of heart failure and adverse health outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Tob. Induc. Dis. 2020, 18, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaviarasan, V.; Mohammed, V.; Veerabathiran, R. Genetic predisposition study of heart failure and its association with cardiomyopathy. Egypt. Heart J. 2022, 74, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heidenreich, P.A.; Bozkurt, B.; Aguilar, D.; Allen, L.A.; Byun, J.J.; Colvin, M.M.; Deswal, A.; Drazner, M.H.; Dunlay, S.M.; Evers, L.R.; et al. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2022, 145, e895–e1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, A.; Etemad, K.; Khaledifar, A. Risk factors for heart failure in a cohort of patients with newly diagnosed myocardial infarction: A matched, case-control study in Iran. Epidemiol. Health 2016, 38, e2016019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouqata, N.; Kheyi, J.; Miftah, F.; Sabor, H.; Bouziane, A.; Bouzelmat, H.; Chaib, A.; Benyass, A.; Moustaghfir, A. Epidemiological and evolutionary characteristics of heart failure in patients with left bundle branch block—A Moroccan center-based study. J. Saudi Heart Assoc. 2015, 27, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, M.; Alharbi, F.; AlTuwayjiri, A.; Alharbi, Y.; Alhofair, Y.; Alanazi, A.; AlJlajle, F.; Khalil, R.; Al-Wutayd, O. Assessment of health-related quality of life in patients with heart failure: A cross-sectional study in Saudi Arabia. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2022, 20, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walli-Attaei, M.; Joseph, P.; Johansson, I.; Sliwa, K.; Lonn, E.; Maggioni, A.P.; Mielniczuk, L.; Ross, H.; Karaye, K.; Hage, C.; et al. Characteristics, management, and outcomes in women and men with congestive heart failure in 40 countries at different economic levels: An analysis from the Global Congestive Heart Failure (G-CHF) registry. Lancet Glob. Health 2024, 12, e396–e405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celik, A.; Ural, D.; Sahin, A.; Colluoglu, I.T.; Kanik, E.A.; Ata, N.; Arugaslan, E.; Demir, E.; Ayvali, M.O.; Ulgu, M.M.; et al. Trends in heart failure between 2016 and 2022 in Türkiye (TRends-HF): A nationwide retrospective cohort study of 85 million individuals across entire population of all ages. Lancet Reg. Health–Eur 2023, 33, 100723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kingery, J.R.; Roberts, N.L.; Lookens Pierre, J.; Sufra, R.; Dade, E.; Rouzier, V.; Malebranche, R.; Theard, M.; Goyal, P.; Pirmohamed, A.; et al. Population-Based Epidemiology of Heart Failure in a Low-Income Country: The Haiti Cardiovascular Disease Cohort. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2023, 16, e009093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, S.; Miranda, J.J.; Mamas, M.A.; Zühlke, L.J.; Kontopantelis, E.; Thabane, L.; Van Spall, H.G.C. Sex differences in the etiology and burden of heart failure across country income level: Analysis of 204 countries and territories 1990–2019. Eur. Heart J. Qual. Care Clin. Outcomes 2023, 9, 662–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukhbaatar, P.; Bayartsogt, B.; Ulziisaikhan, G.; Byambatsogt, B.; Khorloo, C.; Badrakh, B.; Tserendavaa, S.; Sodovsuren, N.; Dagva, M.; Khurelbaatar, M.U.; et al. The Prevalence and Risk Factors of Chronic Heart Failure in the Mongolian Population. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Störk, S.; Handrock, R.; Jacob, J.; Walker, J.; Calado, F.; Lahoz, R.; Hupfer, S.; Klebs, S. Epidemiology of heart failure in Germany: A retrospective database study. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 2017, 106, 913–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díez, J.; Butler, J. Growing Heart Failure Burden of Hypertensive Heart Disease: A Call to Action. Hypertension 2023, 80, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triposkiadis, F.; Sarafidis, P.; Briasoulis, A.; Magouliotis, D.E.; Athanasiou, T.; Skoularigis, J.; Xanthopoulos, A. Hypertensive Heart Failure. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 5090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, J.; Heidenreich Paul, A.; Kohsaka, S.; Fearon William, F.; Sandhu Alexander, T. Variability in Coronary Artery Disease Testing for Patients with New-Onset Heart Failure. JACC 2022, 79, 849–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velagaleti, R.S.; Vasan, R.S. Heart failure in the twenty-first century: Is it a coronary artery disease or hypertension problem? Cardiol. Clin. 2007, 25, 487–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell-Quintero, S.; Echeverría, L.E.; Gómez-Mesa, J.E.; Rivera-Toquica, A.; Rentería-Asprilla, C.A.; López-Garzón, N.A.; Alcalá-Hernández, A.E.; Accini-Mendoza, J.L.; Baquero-Lozano, G.A.; Martínez-Carvajal, A.R.; et al. Comorbidity profile and outcomes in patients with chronic heart failure in a Latin American country: Insights from the Colombian heart failure registry (RECOLFACA). Int. J. Cardiol. 2023, 378, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunlay, S.M.; Givertz, M.M.; Aguilar, D.; Allen, L.A.; Chan, M.; Desai, A.S.; Deswal, A.; Dickson, V.V.; Kosiborod, M.N.; Lekavich, C.L.; et al. Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Heart Failure: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association and the Heart Failure Society of America: This statement does not represent an update of the 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA heart failure guideline update. Circulation 2019, 140, e294–e324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maisel, W.H.; Stevenson, L.W. Atrial fibrillation in heart failure: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, and rationale for therapy. Am. J. Cardiol. 2003, 91, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorter, T.M.; van Veldhuisen, D.J.; Mulder, B.A.; Artola Arita, V.A.; van Empel, V.P.M.; Manintveld, O.C.; Tieleman, R.G.; Maass, A.H.; Vernooy, K.; van Gelder, I.C.; et al. Prevalence and Incidence of Atrial Fibrillation in Heart Failure with Mildly Reduced or Preserved Ejection Fraction: (Additive) Value of Implantable Loop Recorders. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, J.; Martinez, F.; Calderon, J.M.; Fernandez, A.; Sauri, I.; Uso, R.; Trillo, J.L.; Redon, J.; Forner, M.J. Incidence and impact of atrial fibrillation in heart failure patients: Real-world data in a large community. ESC Heart Fail. 2022, 9, 4230–4239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yogasundaram, H.; Islam, S.; Dover, D.C.; Hawkins, N.M.; Ezekowitz, J.; Kaul, P.; Sandhu, R.K. Nationwide Study of Sex Differences in Incident Heart Failure in Newly Diagnosed Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation. CJC Open 2022, 4, 701–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwab, J.O.; Gricar, B.; Hauser, T. The prevalence of implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) and heart failure patients eligible for remote monitoring in Germany. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2024, 24, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidya, V.R.; Asirvatham, R.; Kowlgi, G.N.; Dai, M.Y.; Cochuyt, J.J.; Hodge, D.O.; Deshmukh, A.J.; Cha, Y.M. Trends in Cardiovascular Implantable Electronic Device Insertion Between 1988 and 2018 in Olmsted County. JACC Clin. Electrophysiol. 2022, 8, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curtis, L.H.; Al-Khatib, S.M.; Shea, A.M.; Hammill, B.G.; Hernandez, A.F.; Schulman, K.A. Sex differences in the use of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators for primary and secondary prevention of sudden cardiac death. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2007, 298, 1517–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, N.A.; Borgquist, R.; Chang, Y.; Lewey, J.; Jackson, V.A.; Singh, J.P.; Metlay, J.P.; Lindvall, C. Increasing sex differences in the use of cardiac resynchronization therapy with or without implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. Eur. Heart J. 2017, 38, 1485–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingelaere, S.; Hoffmann, R.; Guler, I.; Vijgen, J.; Mairesse, G.H.; Blankoff, I.; Vandekerckhove, Y.; le Polain de Waroux, J.B.; Vandenberk, B.; Willems, R. Inequality between women and men in ICD implantation. Int. J. Cardiol. Heart Vasc. 2022, 41, 101075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccia, A.; Damiani, G.; D’Errico, M.M.; Farinaro, E.; Gregorio, P.; Nante, N.; Santè, P.; Siliquini, R.; Ricciardi, G.; La Torre, G.; et al. Age- and sex-related utilisation of cardiac procedures and interventions: A multicentric study in Italy. Int. J. Cardiol. 2005, 101, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowak, B.; Misselwitz, B.; Erdogan, A.; Funck, R.; Irnich, W.; Israel, C.W.; Olbrich, H.-G.; Schmidt, H.; Sperzel, J.; Zegelman, M.; et al. Do gender differences exist in pacemaker implantation?—Results of an obligatory external quality control program. Europace 2009, 12, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yehya, A.; Lopez, J.; Sauer Andrew, J.; Davis Jonathan, D.; Ibrahim Nasrien, E.; Tung, R.; Bozkurt, B.; Fonarow Gregg, C.; Al-Khatib Sana, M. Revisiting ICD Therapy for Primary Prevention in Patients with Heart Failure and Reduced Ejection Fraction. JACC Heart Fail. 2025, 13, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mody, R.; Nee Sheth, A.B.; Dash, D.; Mody, B.; Agrawal, A.; Monga, I.S.; Rastogi, L.; Munjal, A. Device therapies for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: A new era. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2024, 11, 1388232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual-Figal, D.A.; Ferrero-Gregori, A.; Gomez-Otero, I.; Vazquez, R.; Delgado-Jimenez, J.; Alvarez-Garcia, J.; Gimeno-Blanes, J.R.; Worner-Diz, F.; Bardají, A.; Alonso-Pulpon, L.; et al. Mid-range left ventricular ejection fraction: Clinical profile and cause of death in ambulatory patients with chronic heart failure. Int. J. Cardiol. 2017, 240, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Hales, S.; Barin, E.; Tofler, G. Characteristics and outcome for heart failure patients with mid-range ejection fraction. J. Cardiovasc. Med. 2018, 19, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chioncel, O.; Lainscak, M.; Seferovic, P.M.; Anker, S.D.; Crespo-Leiro, M.G.; Harjola, V.P.; Parissis, J.; Laroche, C.; Piepoli, M.F.; Fonseca, C.; et al. Epidemiology and one-year outcomes in patients with chronic heart failure and preserved, mid-range and reduced ejection fraction: An analysis of the ESC Heart Failure Long-Term Registry. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2017, 19, 1574–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickenbacher, P.; Kaufmann, B.A.; Maeder, M.T.; Bernheim, A.; Goetschalckx, K.; Pfister, O.; Pfisterer, M.; Brunner-La Rocca, H.P. Heart failure with mid-range ejection fraction: A distinct clinical entity? Insights from the Trial of Intensified versus standard Medical therapy in Elderly patients with Congestive Heart Failure (TIME-CHF). Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2017, 19, 1586–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, B. Angiotensin Receptor-Neprilysin Inhibition (ARNI) in Heart Failure. Int. J. Heart Fail. 2020, 2, 73–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zannad, F.; Ferreira, J.P.; Pocock, S.J.; Anker, S.D.; Butler, J.; Filippatos, G.; Brueckmann, M.; Ofstad, A.P.; Pfarr, E.; Jamal, W.; et al. SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: A meta-analysis of the EMPEROR-Reduced and DAPA-HF trials. Lancet 2020, 396, 819–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold Suzanne, V.; Silverman Daniel, N.; Gosch, K.; Nassif Michael, E.; Infeld, M.; Litwin, S.; Meyer, M.; Fendler Timothy, J. Beta-Blocker Use and Heart Failure Outcomes in Mildly Reduced and Preserved Ejection Fraction. JACC Heart Fail. 2023, 11, 893–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fusco, S.A.; Alonzo, A.; Aimo, A.; Matteucci, A.; Intravaia, R.C.M.; Aquilani, S.; Cipriani, M.; De Luca, L.; Navazio, A.; Valente, S.; et al. ANMCO Position paper: Vericiguat use in heart failure: From evidence to place in therapy. G. Ital. Cardiol. 2023, 24, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Fusco, S.A.; Aquilani, S.; Spinelli, A.; Alonzo, A.; Matteucci, A.; Castello, L.; Imperoli, G.; Colivicchi, F. The polypill strategy in cardiovascular disease prevention: It’s time for its implementation. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2023, 79, 37–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savarese, G.; Becher, P.M.; Lund, L.H.; Seferovic, P.; Rosano, G.M.C.; Coats, A.J.S. Global burden of heart failure: A comprehensive and updated review of epidemiology. Cardiovasc. Res. 2023, 118, 3272–3287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiga, T.; Suzuki, A.; Haruta, S.; Mori, F.; Ota, Y.; Yagi, M.; Oka, T.; Tanaka, H.; Murasaki, S.; Yamauchi, T.; et al. Clinical characteristics of hospitalized heart failure patients with preserved, mid-range, and reduced ejection fractions in Japan. ESC Heart Fail. 2019, 6, 475–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiroz, R.; Doros, G.; Shaw, P.; Liang, C.S.; Gauthier, D.F.; Sam, F. Comparison of characteristics and outcomes of patients with heart failure preserved ejection fraction versus reduced left ventricular ejection fraction in an urban cohort. Am. J. Cardiol. 2014, 113, 691–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rywik, T.M.; Wiśniewska, A.; Cegłowska, U.; Drohomirecka, A.; Topór-Mądry, R.; Łazarczyk, H.; Połaska, P.; Zieliński, T.; Doryńska, A. Heart failure with reduced, mildly reduced, and preserved ejection fraction: Outcomes and predictors of prognosis. Pol. Arch. Intern. Med. 2023, 133, 16522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapłon-Cieślicka, A.; Benson, L.; Chioncel, O.; Crespo-Leiro, M.G.; Coats, A.J.S.; Anker, S.D.; Filippatos, G.; Ruschitzka, F.; Hage, C.; Drożdż, J.; et al. A comprehensive characterization of acute heart failure with preserved versus mildly reduced versus reduced ejection fraction—Insights from the ESC-HFA EORP Heart Failure Long-Term Registry. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2022, 24, 335–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, J.H.; Choe, W.S.; Cho, H.J.; Lee, H.Y.; Jang, J.; Lee, S.E.; Choi, J.O.; Jeon, E.S.; Kim, M.S.; Hwang, K.K.; et al. Comparison of Characteristics and 3-Year Outcomes in Patients with Acute Heart Failure with Preserved, Mid-Range, and Reduced Ejection Fraction. Circ. J. 2019, 83, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, M.; Bian, B.; Yang, Q. Characteristics and long-term prognosis of patients with reduced, mid-range, and preserved ejection fraction: A systemic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Cardiol. 2022, 45, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguayo Cano, N.; Perea Armijo, J.; Lopez Aguilera, J.; Castillo Dominguez, J.C.; Anguita Sanchez, M.; Pan Alvarez-Ossorio, M. Correlation between chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: Is it just a comorbidity? Eur. Heart J. 2025, 46, ehaf784.975. [Google Scholar]

- Heerspink Hiddo, J.L.; Neuen Brendon, L.; Inker Lesley, A. Chronic Kidney Disease Progression in Heart Failure. JACC Heart Fail. 2024, 12, 860–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bytyçi, I.; Bajraktari, G. Mortality in heart failure patients. Anatol. J. Cardiol. 2015, 15, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amornritvanich, P.; Ratanatharathorn, C.; Tansawet, A.; Yingchoncharoen, T.; Looareesuwan, P.; Pattanateepapon, A.; Attia, J.; Mckay, G.J.; Thakkinstian, A. SGLT2i and ARNI improve long-term heart failure outcomes: A multi-state model analysis from a real-world southeast asian cohort. Eur. Heart J. 2025, 46, ehaf784.1288. [Google Scholar]

- Vaartjes, I.; Hoes, A.W.; Reitsma, J.B.; de Bruin, A.; Grobbee, D.E.; Mosterd, A.; Bots, M.L. Age- and gender-specific risk of death after first hospitalization for heart failure. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Navarro, M.F.; Ramirez-Marrero, M.A.; Anguita-Sánchez, M.; Castillo, J.C. Influence of gender on long-term prognosis of patients with chronic heart failure seen in heart failure clinics. Clin. Cardiol. 2010, 33, E13–E18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakata, Y.; Miyata, S.; Nochioka, K.; Miura, M.; Takada, T.; Tadaki, S.; Takahashi, J.; Shimokawa, H. Gender differences in clinical characteristics, treatment and long-term outcome in patients with stage C/D heart failure in Japan. Report from the CHART-2 study. Circ. J. 2014, 78, 428–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gama, F.; Ferreira, J.; Carmo, J.; Costa, F.M.; Carvalho, S.; Carmo, P.; Cavaco, D.; Morgado, F.B.; Adragão, P.; Mendes, M. Implantable Cardioverter–Defibrillators in Trials of Drug Therapy for Heart Failure: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020, 9, e015177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | n = 835 (%) |

|---|---|

| Previous HF diagnosis | 391 (46.8) |

| Age [IQR] (years) | 70.0 [62.0–79.0] |

| Male | 508 (60.8) |

| Smoking | 605 (72.5) |

| BMI [IQR] (kg/m2) | 28.7 [24.8–32.6] |

| Normal weight | 188 (22.5) |

| Overweight | 255 (30.5) |

| Obese | 320 (38.3) |

| Previous cardiac surgery | 316 (37.8) |

| Device implant | 208 (24.9) |

| SBP [IQR] (mmHg) | 127.5 [110.0–140.0] |

| HR [IQR] (bpm) | 80.0 [70.0–92.0] |

| HTN | 703 (84.2) |

| DM | 461 (55.2) |

| DLP | 197 (23.6) |

| CKD | 211 (25.2) |

| Thyroid disease | 81 (9.7) |

| COPD | 168 (20.1) |

| CAD | 623 (74.6) |

| AFib | 279 (33.4) |

| Length of stay [IQR] (days) | 6.0 [4.0–9.0] |

| Hospitalization > 7 days | 275 (32.9) |

| Troponin [IQR] (ng/L) | 0.04 [0.02–0.1] |

| CRP [IQR] (mg/dL) | 1.5 [0.7–4.9] |

| BNP [IQR] (pg/mL) | 1038.1 [451.0–2228.1] |

| TSH [IQR] (µIU/mL) | 1.6 [0.7–3.0] |

| eGFR [IQR] (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 50.9 [36.5–74.9] |

| In-hospital mortality | 259 (31.0) |

| Characteristic | Male n = 508 (%) | Female n = 327 (%) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Previous HF diagnosis | 233 (45.9) | 158 (48.3) | 0.488 |

| Age ≥ 70 (years) | 226 (44.5) | 212 (64.8) | <0.005 |

| Smoking | 412 (81.1) | 193 (59.0) | <0.005 |

| BMI [IQR] (kg/m2) | 28.1 [24.8–31.6] | 29.1 [25.2–34.2] | 0.064 |

| Previous cardiac surgery | 193 (38.0) | 123 (37.6) | 0.913 |

| Device Implant | |||

| ICD | 87 (17.1) | 28 (8.6) | <0.001 |

| CRT-D | 45 (8.9) | 12 (3.7) | 0.004 |

| Pacemaker | 14 (2.8) | 22 (6.7) | 0.006 |

| HTN | 418 (82.3) | 285 (87.2) | 0.06 |

| DM | 270 (53.1) | 191 (58.4) | 0.136 |

| DLP | 117 (23.0) | 80 (24.5) | 0.634 |

| CKD | 131 (25.8) | 80 (24.5) | 0.668 |

| COPD | 94 (18.5) | 74 (22.6) | 0.147 |

| CAD | 398 (78.3) | 225 (68.8) | 0.002 |

| AFib | 150 (29.5) | 129 (39.4) | 0.003 |

| Length of stay > 7 days | 174 (34.3) | 101 (30.9) | 0.313 |

| One-year re-admission ≥ 2 times due to HF | 76 (15.0) | 45 (13.8) | 0.631 |

| In-hospital mortality | 152 (29.9) | 107 (32.7) | 0.393 |

| Characteristic | HFpEF (EF ≥ 50%) n = 251 (%) | HFmrEF (EF 41–49%) n = 113 (%) | HFrEF (EF ≤ 40%) n = 471 (%) | Overall p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| De Novo diagnosis | 156 (62.2) a | 67 (59.3) a,b | 221 (46.9) b | <0.005 |

| Male | 106 (42.2) a | 62 (54.9) a | 340 (72.2) c | <0.005 |

| Age ≥ 70 | 171 (68.1) a | 74 (65.5) a | 193 (41.0) c | <0.005 |

| Smoking | 162 (64.5) a | 84 (74.3) a,b | 359 (76.2) b | 0.003 |

| BMI [IQR] (kg/m2) | 29.7 [25.5–34.8] | 28.7 [24.4–33.7] | 28.3 [24.7–31.3] | 0.055 |

| Previous cardiac surgery | 94 (37.5) | 49 (43.4) | 173 (36.7) | 0.421 |

| Type of implanted device | ||||

| ICD | 12 (4.8) a | 3 (2.7) a | 100 (21.2) c | <0.001 |

| CRT-D | 4 (1.6) a | 3 (2.7) a | 50 (10.6) c | <0.001 |

| Pacemaker | 18 (7.2) b | 3 (2.7) a,b | 15 (3.2) a | 0.028 |

| HTN | 225 (89.6) a | 100 (88.5) a,b | 378 (80.3) b | 0.002 |

| DM | 133 (53.0) | 67 (59.3) | 261 (55.4) | 0.539 |

| DLP | 59 (23.5) | 36 (31.9) | 102 (21.7) | 0.072 |

| CKD | 62 (24.7) | 30 (26.5) | 119 (25.3) | 0.936 |

| COPD | 51 (20.3) | 28 (24.8) | 89 (18.9) | 0.383 |

| CAD | 169 (67.3) c | 90 (79.6) a | 364 (77.3) a | 0.006 |

| AFib | 99 (39.4) a | 43 (38.1) a,b | 137 (29.1) b | 0.010 |

| Length of stay > 7 days | 74 (29.5) | 37 (32.7) | 164 (34.8) | 0.351 |

| One-year re-admission ≥ 2 times due to HF | 32 (12.7) | 17 (15.0) | 72 (15.3) | 0.661 |

| In-hospital mortality | 74 (259) | 31 (27.4) | 154 (32.7) | 0.455 |

| Home Medication | HFpEF (EF ≥ 50%) n = 251 (%) | HFmrEF (EF 41–49%) n = 113 (%) | HFrEH (EF ≤ 40%) n = 471 (%) | Overall p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARNI | 17 (6.8) a | 13 (11.5) a | 127 (27.0) c | <0.005 |

| SGLT2i | 27 (10.8) a | 11 (9.7) a | 106 (22.5) c | <0.005 |

| MRA | 91 (36.3) | 46 (40.7) | 203 (43.1) | 0.204 |

| Beta-blocker | 211 (84.1) a | 107 (94.7) b | 416 (88.3) a,b | 0.015 |

| Class III AAD | 42 (16.7) a | 21 (18.6) a,b | 119 (25.3) b | 0.020 |

| Class IV AAD | 86 (34.3) a | 36 (31.9) a | 69 (20.4) c | <0.005 |

| ACEi | 55 (21.9) a | 34 (30.1) a,b | 187 (39.7) b | <0.005 |

| ARB | 64 (25.5) a | 28 (24.8) a,b | 78 (16.6) b | 0.008 |

| Allopurinol | 58 (23.1) | 21 (18.6) | 94 (20.0) | 0.509 |

| Anticoagulant | 165 (65.7) | 76 (67.3) | 296 (62.8) | 0.580 |

| Antiplatelet | 192 (76.5) | 92 (81.4) | 392 (83.2) | 0.089 |

| Diuretic | 213 (84.9) | 100 (88.5) | 424 (90.0) | 0.121 |

| Statin | 173 (68.9) | 87 (77.0) | 356 (75.6) | 0.108 |

| Variable | β | p-Value | HR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.183 | 0.237 | 1.200 | 0.887–1.624 |

| Age ≥ 70 years | 0.265 | 0.079 | 1.304 | 0.969–1.753 |

| Smoking | 0.256 | 0.137 | 1.292 | 0.922–1.812 |

| Obesity | −0.158 | 0.264 | 0.854 | 0.646–1.127 |

| HTN | −0.301 | 0.142 | 0.740 | 0.495–1.106 |

| DM | 0.093 | 0.522 | 1.097 | 0.826–1.457 |

| CKD | 0.544 | <0.001 | 1.722 | 1.278–2.321 |

| COPD | 0.377 | 0.014 | 1.458 | 1.080–1.968 |

| CAD | 0.041 | 0.819 | 1.042 | 0.732–1.484 |

| AFib | 0.201 | 0.155 | 1.222 | 0.927–1.613 |

| ARNI | −0.423 | 0.041 | 0.655 | 0.437–0.983 |

| SGLT2i | −0.432 | 0.035 | 0.649 | 0.435–0.969 |

| ACEi | −0.103 | 0.493 | 0.902 | 0.672–1.211 |

| ARB | −0.161 | 0.362 | 0.851 | 0.602–1.204 |

| EF ≤ 40% | 0.490 | 0.002 | 1.633 | 1.203–2.217 |

| ICD | −0.274 | 0.199 | 0.761 | 0.501–1.155 |

| CRT-D | −0.083 | 0.765 | 0.921 | 0.535–1.583 |

| Pacemaker | −0.013 | 0.966 | 0.987 | 0.543–1.796 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 0.326 | 0.056 | 1.385 | 0.991–1.935 |

| BNP (pg/mL) | 0.243 | 0.281 | 1.275 | 0.820–1.985 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Saker, Z.; Hamieh, M.; Abdel-Sater, F.; Rabah, A. Heart Failure in Lebanon: A Glimpse into the Reality of Growing Burden. Diagnostics 2026, 16, 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010057

Saker Z, Hamieh M, Abdel-Sater F, Rabah A. Heart Failure in Lebanon: A Glimpse into the Reality of Growing Burden. Diagnostics. 2026; 16(1):57. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010057

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaker, Zahraa, Mohamad Hamieh, Fadi Abdel-Sater, and Ali Rabah. 2026. "Heart Failure in Lebanon: A Glimpse into the Reality of Growing Burden" Diagnostics 16, no. 1: 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010057

APA StyleSaker, Z., Hamieh, M., Abdel-Sater, F., & Rabah, A. (2026). Heart Failure in Lebanon: A Glimpse into the Reality of Growing Burden. Diagnostics, 16(1), 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010057