Shape and Morphology of the Sella Turcica in Patients with Trisomy 21—A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

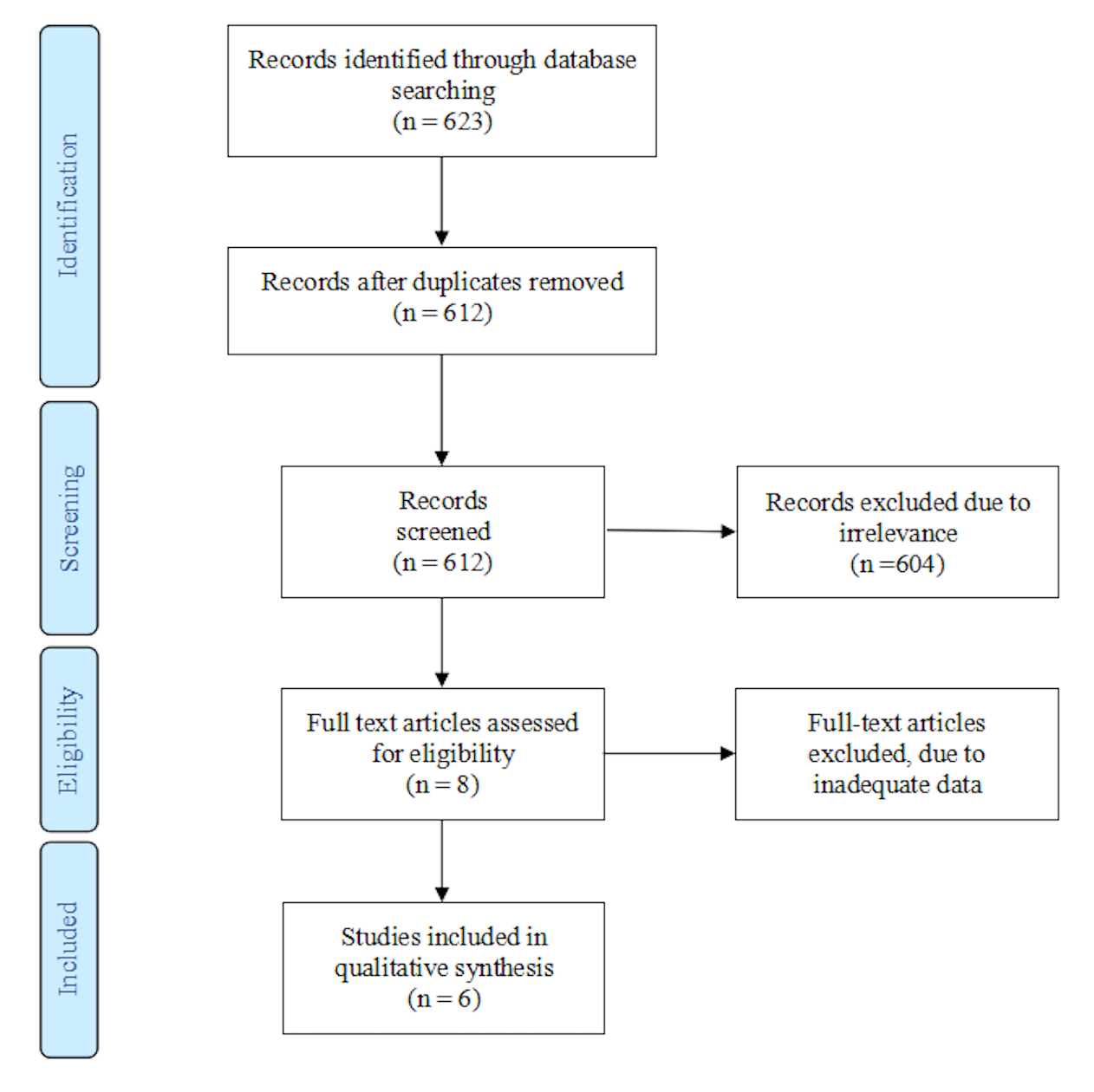

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Criteria

2.1.1. Full Electronic Search Strategy

2.1.2. Inclusion Criteria

- P.

- Individuals with trisomy 21 (Down syndrome).

- I.

- Radiological examination of sella turcica (lateral cephalograms, cone-beam computed tomography scans).

- C.

- Comparison of sella turcica morphology between individuals with trisomy 21 and non-syndromic controls.

- O.

- Evaluation of sella turcica morphology, including size, shape, and any deviations present in individuals with trisomy 21.

2.1.3. Exclusion Criteria

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Quality Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Literature Search

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Risk of Bias

3.3.1. ROBINS-I

3.3.2. Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS)

4. Discussion

4.1. Findings of Individual Studies

4.2. Cross-Study Comparison and Conflicting Results

4.3. Sex-Related and Age-Related Findings

4.4. Clinical Implications

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ST | Sella Turcica |

| DS | Down Syndrome |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| GA | Gestational Age |

References

- Sathyanarayana, H.P.; Kailasam, V.; Chitharanjan, A.B. Sella turcica-Its importance in orthodontics and craniofacial morphology. Dent. Res. J. (Isfahan) 2013, 10, 571–575. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kjær, I. Sella turcica morphology and the pituitary gland—A new contribution to craniofacial diagnostics based on histology and neuroradiology. Eur. J. Orthod. 2015, 37, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iskra, T.; Stachera, B.; Możdżeń, K.; Murawska, A.; Ostrowski, P.; Bonczar, M.; Gregorczyk-Maga, I.; Walocha, J.; Koziej, M.; Wysiadecki, G.; et al. Morphology of the Sella Turcica: A Meta-Analysis Based on the Results of 18,364 Patients. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roomaney, I.A.; Chetty, M. Sella turcica morphology in patients with genetic syndromes: A systematic review. Orthod. Craniofacial Res. 2021, 24, 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moffitt, A.H. Discovery of pathologies by orthodontists on lateral cephalograms. Angle Orthod. 2011, 81, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silverman, F.N. Roentgen standards fo-size of the pituitary fossa from infancy through adolescence. Am. J. Roentgenol. Radium Ther. Nucl. Med. 1957, 78, 451–460. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kisling, E. Cranial Morphology in Down’s Syndrome: A Comparative Roentgenencephalometric Study in Adult Males; Munksgaard: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Jankowski, T.; Jedliński, M.; Grocholewicz, K.; Janiszewska-Olszowska, J. Sella Turcica Morphology on Cephalometric Radiographs and Dental Abnormalities-Is There Any Association?—Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alessandri-Bonetti, A.; Guglielmi, F.; Mollo, A.; Sangalli, L.; Gallenzi, P. Prevalence of Malocclusions in Down Syndrome Population: A Cross-Sectional Study. Medicina 2023, 59, 1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vicente, A.; Bravo-González, L.A.; López-Romero, A.; Muñoz, C.S.; Sánchez-Meca, J. Craniofacial morphology in Down Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khurana, S.; Khalifa, A.R.; Rezallah, N.N.; Lozanoff, S.; Abdelkarim, A.Z. Craniofacial and Airway Morphology in Down Syndrome: A Cone Beam Computed Tomography Case Series Evaluation. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 3908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mengxia, P.; Algahefi, A.L.; Halboub, E.; Qassem, A.S.A.M.; Li, Z.; Alhammadi, M.S. Dimensions and Morphology of Sella Turcica in Different Skeletal Malocclusions: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Odontology 2025, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterne, J.A.; Hernán, M.A.; Reeves, B.C.; Savović, J.; Berkman, N.D.; Viswanathan, M.; Henry, D.; Altman, D.G.; Ansari, M.T.; Boutron, I.; et al. ROBINS-I: A tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 2016, 355, i4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. Available online: https://www.ohri.ca/Programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Russell, B.G.; Kjaer, I. Postnatal structure of the sella turcica in Down syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1999, 87, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjær, I.; Keeling, J.W.; Reintoft, I.; Nolting, D.; Hansen, B.F. Pituitary gland and sella turcica in human trisomy 21 fetuses related to axial skeletal development. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1998, 80, 494–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korayem, M.; Alkofide, E. Size and shape of the sella turcica in subjects with Down syndrome. Orthod. Craniofac Res. 2015, 18, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasan, H.A.; Hameed, H.A.; Alam, M.K.; Yusof, A.; Murakami, H.; Kubo, K.; Maeda, H. Sella turcica morphology phenotyping in Malay subjects with Down’s syndrome. J. Hard Tissue Biol. 2019, 28, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaefthymiou, P.; Ozbilen, E.O. Sella turcica morphometrics in subjects with Down syndrome. J. Stomatol. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2023, 124, 101559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aghimien, O. Size and shape of sella turcica among Down syndrome individuals in a Nigerian population. West. Afr. J. Radiol. 2022, 29, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference | Methodology | Study Population | ST Measurements | Shape Classification | Key Findings | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kjær et al. 1998 Denmark [17] | Retrospective Histological and radiological | 22 DS human fetuses (GA 14–21 weeks) | Qualitative assessment of the ST region | Author-defined (4 morphological types) | Minor to marked anterior sella changes; associated axial anomalies | No control group; very small sample; subjective classification |

| Russell and Kjær 1999 Denmark [16] | Observational Lateral cephalograms | 78 DS; 4 months–50 years | Qualitative description | Author-defined (3 shape types) | Majority with near-normal morphology; few anterior/floor deviations | No control group; subjective classification |

| Korayem and AlKofide 2015 Saudi Arabia [18] | Observational Lateral cephalograms | 60 DS, 60 controls 12–22 years | Linear: length, depth, diameter | Standardized (Axelsson classification) | DS individuals showed increased depth and diameter and more shape deviations | Small sample; no longitudinal data |

| Hasan et al. 2019 Malaysia [19] | Observational CT scan | 50 DS, 50 controls; 0–35 years | Linear: heights (A/M/P), length, width, diameter, area | Modified standardized morphological criteria (U, J, shallow) | Several dimensions differed significantly; DS had U/J predominance | Sample limited to one population; generalizability limited |

| Aghimien 2022 Nigeria [21] | Cross-sectional descriptive Lateral cephalograms | 29 DS (size), 25 DS. 10–20 years | Linear: length, depth, diameter | Author-defined | Shorter length; pyramidal shape common; sex-related variation | Small sample; no control group; indirect norm comparison |

| Papaefthymiou et al. 2023 Turkey [20] | Retrospective Lateral cephalograms | 24 DS, 48 controls. 8–13 years | Linear: heights, length, width, area; geometric shape analysis | Standardized morphometric analysis (Procrustes + PCA) | DS group showed increased dimensions and distinct shape patterns | Small sample; no advanced imaging |

| Reference | Confounding | Selection of Participants | Classification of Interventions | Deviations from Intended Interventions | Missing Data | Measurement of Outcomes | Selection of Reported Result | Overall Risk of Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kjær et al. 1998 [17] | Serious | Serious | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Serious |

| Russell and Kjær 1999 [16] | Serious | Serious | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Serious |

| Korayem and AlKofide 2015 [18] | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| Hasan et al. 2019 [19] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Aghimien 2022 [21] | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| Papaefthymiou et al. 2023 [20] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Reference | Representativeness of the Exposed Cohort (S) | Selection of the Non-Exposed Cohort (S) | Ascertainment of Exposure (S) | Demonstration that Outcome Was Not Present at Start (S) | Comparability of Cohorts on Design or Analysis (C) | Assessment of Outcome (O) | Was Follow-Up Long Enough for Outcomes to Occur (O) | Adequacy of Follow-Up of Cohorts (O) | Total Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kjær et al. 1998 [17] | ★ | - | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | - | ★ | 6/9 |

| Russell and Kjær 1999 [16] | ★ | - | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | - | ★ | 6/9 |

| Korayem and AlKofide 2015 [18] | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 8/9 |

| Hasan et al. 2019 [19] | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 9/9 |

| Aghimien 2022 [21] | ★ | - | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | - | ★ | 6/9 |

| Papaefthymiou et al. 2023 [20] | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 8/9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mazuś, M.; Szemraj-Folmer, A.; Stasiak, M.; Studniarek, M. Shape and Morphology of the Sella Turcica in Patients with Trisomy 21—A Systematic Review. Diagnostics 2026, 16, 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010022

Mazuś M, Szemraj-Folmer A, Stasiak M, Studniarek M. Shape and Morphology of the Sella Turcica in Patients with Trisomy 21—A Systematic Review. Diagnostics. 2026; 16(1):22. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010022

Chicago/Turabian StyleMazuś, Magda, Agnieszka Szemraj-Folmer, Marcin Stasiak, and Michał Studniarek. 2026. "Shape and Morphology of the Sella Turcica in Patients with Trisomy 21—A Systematic Review" Diagnostics 16, no. 1: 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010022

APA StyleMazuś, M., Szemraj-Folmer, A., Stasiak, M., & Studniarek, M. (2026). Shape and Morphology of the Sella Turcica in Patients with Trisomy 21—A Systematic Review. Diagnostics, 16(1), 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010022