Incidence Rates and Diagnostic Trends of Perioperative Acute Transverse Myelitis in Patients Who Underwent Surgery for Degenerative Spinal Diseases: A Nationwide Epidemiologic Study of 201,769 Patients

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Database

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Identification of ATM

2.4. Definition of Perioperative Period

2.5. Variables and Comorbidities

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

3.2. Diagnostic Confirmation and Annual Incidence

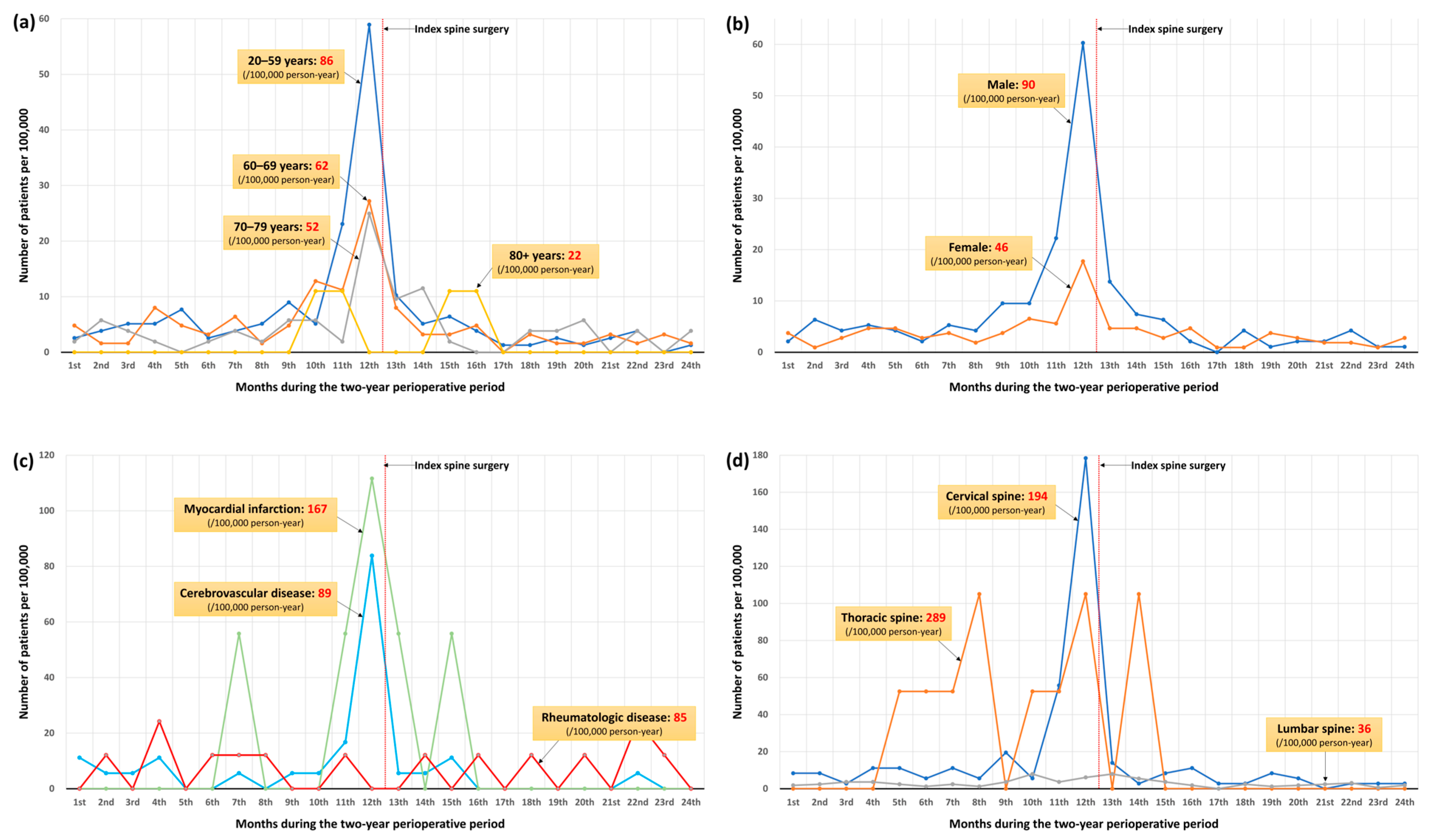

3.3. Patient Characteristics

3.4. Factors Associated with Occurrence of ATM: Multivariable Analysis

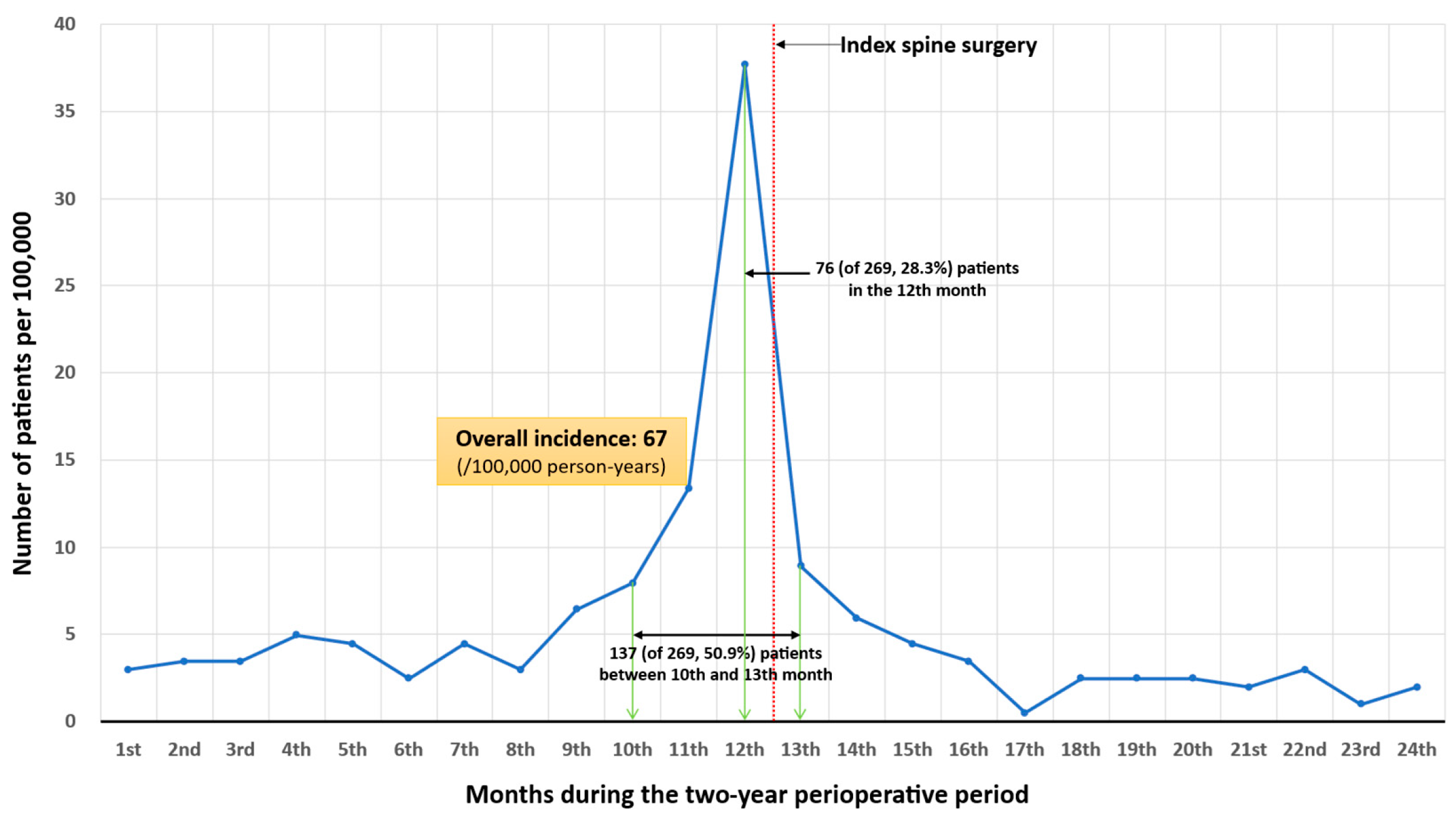

3.5. Perioperative Diagnostic Trend of ATM

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Category of Steroid | Type of Steroid | ATC Code | HIRA General Name Code |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oral steroid | deflazacort 6 mg | H02AB13 | 140801ATB |

| dexamethasone 0.5 mg | H02AB02 | 141901ATB | |

| dexamethasone 0.75 mg | H02AB02 | 141903ATB | |

| betamethasone 0.25 mg + d-chlorpheniramine 2 mg | H02AB01 | 296900ATB | |

| hydrocortisone 10 mg | H02AB09 | 116401ATB | |

| hydrocortisone 5 mg | H02AB09 | 170901ATB | |

| methylprednisolone 4 mg | H02AB04 | 193302ATB | |

| methylprednisolone 1 mg | H02AB04 | 193305ATB | |

| prednisolone 5 mg | H02AB06 | 217001ATB | |

| triamcinolone 1 mg | H02AB08 | 243201ATB | |

| triamcinolone 2 mg | H02AB08 | 243202ATB | |

| triamcinolone 4 mg | H02AB08 | 243203ATB | |

| fludrocortisone 100 μg | H02AA02 | 160201ATB | |

| Intravenous steroid | dexamethasone 4 mg | H02AB02 | 142030BIJ |

| dexamethasone 4 mg | H02AB02 | 142230BIJ | |

| dexamethasone 5 mg | H02AB02 | 142232BIJ | |

| betamethasone 4 mg | H02AB01 | 116530BIJ | |

| hydrocortisone 100 mg | H02AB09 | 171201BIJ | |

| methylprednisolone 125 mg | H02AB04 | 193601BIJ | |

| methylprednisolone 40 mg | H02AB04 | 193603BIJ | |

| methylprednisolone 500 mg | H02AB04 | 193604BIJ | |

| triamcinolone 10 mg | H02AB08 | 243336BIJ | |

| triamcinolone 40 mg | H02AB08 | 243335BIJ | |

| triamcinolone 40 mg | H02AB08 | 243337BIJ |

| Surgical Methods | Spinal Regions | HIRA Therapeutic Codes |

|---|---|---|

| Decompressive surgery | Cervical | N2491, N2492, N0491, N1491, N1497, N2497 |

| Thoracic | N1492, N1498, N2498 | |

| Lumbar | N0492, N1493, N1499, N2499 | |

| Fusion surgery | Cervical | N2461, N0464, N2463, N2467, N2468, N0467, N2469 |

| Thoracic | N0465, N2464, N2465, N2466, N0468 | |

| Lumbar | N0466, N1466, N0469, N1460, N1469, N2470 |

| Variables | Categories | Model 1 (Fully Adjusted) | Model 2 (Bootstrap Validation After Fully Adjusted) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | p-Value | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | Relative Bias (%) | ||

| Age | 60–69 vs. 20–59 | 0.75 [0.56–1.00] | 0.051 | 0.71 [0.55–0.95] | 15.75 |

| 70–79 vs. 20–59 | 0.63 [0.44–0.88] | 0.007 | 0.62 [0.50–0.76] | 1.25 | |

| 80+ vs. 20–59 | 0.26 [0.09–0.70] | 0.008 | 0.24 [0.09–0.37] | 5.97 | |

| Sex | Male vs. female | 1.45 [1.11–1.90] | 0.006 | 1.50 [1.15–1.88] | 8.48 |

| Charlson comorbidity index score | 2–3 vs. 0–1 | 1.58 [0.78–1.20] | 0.086 | 1.60 [0.98–2.64] | 2.54 |

| ≥4 vs. 0–1 | 1.14 [0.37–3.53] | 0.822 | 1.06 [0.43–2.73] | −53.13 | |

| Comorbidities | Myocardial infarction | 2.33 [1.19–5.81] | 0.036 | 2.47 [1.13–5.98] | 6.87 |

| Congestive heart failure | 0.77 [0.33–1.80] | 0.547 | 0.82 [0.46–1.36] | −23.66 | |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 1.65 [1.13–2.42] | 0.010 | 1.63 [1.15–2.54] | −2.58 | |

| Dementia | 1.54 [0.55–4.30] | 0.414 | 0.69 [0–2.72] | −187.75 | |

| Parkinson’s disease | 1.70 [0.54–5.35] | 0.368 | 1.36 [0.51–3.24] | −41.13 | |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 1.07 [0.69–1.66] | 0.770 | 1.07 [0.68–1.65] | −0.13 | |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 0.92 [0.64–1.31] | 0.636 | 0.86 [0.62–1.14] | 71.78 | |

| Rheumatologic disease | 1.90 [1.11–3.84] | 0.042 | 1.84 [1.12–3.71] | −5.27 | |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 0.76 [0.51–1.14] | 0.186 | 0.79 [0.54–1.05] | −11.09 | |

| Liver disease | |||||

| Mild | 0.92 [0.54–1.55] | 0.744 | 0.83 [0.45–1.42] | 108.25 | |

| Moderate to severe | - | - | |||

| Diabetes | |||||

| Uncomplicated | 0.77 [0.33–1.80] | 0.192 | 0.73 [0.56–1.04] | 23.74 | |

| Complicated | 0.94 [0.46–1.94] | 0.875 | 0.93 [0.53–1.80] | 27.85 | |

| Hemiplegia or paraplegia | 1.74 [0.55–5.48] | 0.346 | 1.40 [0.52–3.22] | −39.24 | |

| Renal disease | 0.53 [0.12–2.31] | 0.401 | 0.35 [0–1.61] | 68.51 | |

| End stage renal disease | - | - | |||

| Osteoporosis | 1.06 [0.70–1.63] | 0.778 | 1.08 [0.61–1.40] | 24.82 | |

| Region | Cervical vs. lumbar | 4.75 [3.63–6.21] | <0.001 | 4.86 [4.13–6.14] | 1.45 |

| Thoracic vs. lumbar | 6.61 [3.53–12.36] | <0.001 | 5.85 [3.80–9.54] | −6.42 | |

References

- Frohman, E.M.; Wingerchuk, D.M. Transverse myelitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 564–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beh, S.C.; Greenberg, B.M.; Frohman, T.; Frohman, E.M. Transverse myelitis. Neurol Clin. 2013, 31, 79–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnan, C.; Kaplin, A.I.; Pardo, C.A.; Kerr, D.A.; Keswani, S.C. Demyelinating disorders: Update on transverse myelitis. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2006, 6, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, F.; Zhang, Y.-B. Clinical features and prognosis of patients with guillain-barré and acute transverse myelitis overlap syndrome. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2019, 181, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debette, S.; de Sèze, J.; Pruvo, J.P.; Zephir, H.; Pasquier, F.; Leys, D.; Vermersch, P. Long-term outcome of acute and subacute myelopathies. J. Neurol. 2009, 256, 980–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Oh, S.H.; Kim, S.W.; Kim, T.-H. The epidemiology of concurrent infection in patients with pyogenic spine infection and its association with early mortality: A nationwide cohort study based on 10,695 patients. J. Infect. Public Health 2023, 16, 981–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stavem, K.; Hoel, H.; Skjaker, S.A.; Haagensen, R. Charlson comorbidity index derived from chart review or administrative data: Agreement and prediction of mortality in intensive care patients. Clin. Epidemiol. 2017, 9, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borenstein, M.; Hedges, L.V.; Higgins, J.P.; Rothstein, H.R. Introduction to Meta-Analysis; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, J.; Wu, D.I.; Li, J.; Wang, Q.; Su, J.; Xu, D.; Wang, Y.; Li, M.; et al. Clinical features of transverse myelitis associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 2020, 29, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhat, A.; Naguwa, S.; Cheema, G.; Gershwin, M.E. The epidemiology of transverse myelitis. Autoimmun. Rev. 2010, 9, A395–A399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, S.J.; Williams, C.S.; Román, G.C. Myelopathy in sjögren’s syndrome: Role of nonsteroidal immunosuppressants. Drugs 2004, 64, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goh, C.; Desmond, P.M.; Phal, P.M.J.J.o.M.R.I. Mri in transverse myelitis. J. Magn. Reason. Imaging 2014, 40, 1267–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Transverse Myelitis Consortium Working Group. Proposed diagnostic criteria and nosology of acute transverse myelitis. Neurology 2002, 59, 499–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Year | Spinal Surgery (n) | (n) | Incidence (per 100,000 Person-Year) | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 40,602 | 40 | 49 | [28–71] |

| 2015 | 38,847 | 37 | 48 | [32–63] |

| 2016 | 40,926 | 48 | 59 | [42–75] |

| 2017 | 40,457 | 61 | 75 | [56–94] |

| 2018 | 40,937 | 83 | 101 | [80–123] |

| All | 201,769 | 269 | 67 | [59–75] |

| Variables | Categories | All | Patients Without Acute Transverse Myelitis (n = 201,500) | Patients with Acute Transverse Myelitis (n = 269) | Standardized Mean Difference | Incidence Rates (per 100,000 Person-Year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Mean ± SD | 62.1 ± 12.0 | 62.2 ± 12.0 | 59.1 ± 12.2 | 0.258 | |

| 20–59 | 78,049 | 77,915 (38.7) | 134 (49.8) | 86 | ||

| 60–69 | 62,516 | 62,439 (31) | 77 (28.6) | 62 | ||

| 70–79 | 52,116 | 52,062 (25.8) | 54 (20.1) | 52 | ||

| 80+ | 9088 | 9084 (4.5) | 4 (1.5) | 22 | ||

| Sex | Male | 94,528 | 94,357 (46.8) | 171 (63.6) | 0.377 | 90 |

| Female | 107,241 | 107,143 (53.2) | 98 (36.4) | 46 | ||

| Region | Urban | 167,931 | 167,702 (83.2) | 229 (85.1) | 0.079 | 68 |

| Rural | 33,838 | 33,798 (16.8) | 40 (14.9) | 59 | ||

| Hospital | Tertiary | 35,108 | 34,999 (17.4) | 109 (40.5) | 0.648 | 155 |

| General | 39,997 | 39,931 (19.8) | 66 (24.5) | 83 | ||

| Others | 126,664 | 126,570 (62.8) | 94 (34.9) | 37 |

| Variables | Categories | All | Patients Without Acute Transverse Myelitis (n = 201,500) | Patients with Acute Transverse Myelitis (n = 269) | Standardized Mean Difference | Incidence Rates (per 100,000 Person-Year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Charlson comorbidity index score | Mean ± SD | 1.14 ± 1.28 | 1.14 ± 1.28 | 1.21 ± 1.30 | 0.055 | |

| 0–1 | 141,802 | 141,629 (70.3) | 173 (64.3) | 61 | ||

| 2–3 | 48,414 | 48,333 (24) | 81 (30.1) | 84 | ||

| ≥4 | 11,553 | 11,538 (5.7) | 15 (5.6) | 65 | ||

| Comorbidities | Myocardial infarction | 1792 | 1787 (0.9) | 6 (2.2) | 0.516 | 167 |

| Congestive heart failure | 6329 | 6323 (3.1) | 6 (2.2) | 0.193 | 47 | |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 17,894 | 17,862 (8.9) | 32 (11.9) | 0.181 | 89 | |

| Dementia | 2239 | 2235 (1.1) | 4 (1.5) | 0.164 | 89 | |

| Parkinson’s disease | 1557 | 1554 (0.8) | 3 (1.1) | 0.205 | 96 | |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 21,991 | 21,961 (10.9) | 30 (11.2) | 0.014 | 68 | |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 46,358 | 46,301 (23) | 57 (21.2) | 0.057 | 61 | |

| Rheumatologic disease | 8251 | 8242 (4.1) | 14 (5.2) | 0.139 | 85 | |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 34,894 | 34,856 (17.3) | 38 (14.1) | 0.132 | 54 | |

| Liver disease | ||||||

| Mild | 12,571 | 12,553 (6.2) | 18 (6.7) | 0.042 | 72 | |

| Moderate to severe | 163 | 163 (0.1) | 0 (0) | - | 0 | |

| Diabetes | ||||||

| Uncomplicated | 42,078 | 42,031 (20.9) | 47 (17.5) | 0.121 | 56 | |

| Complicated | 12,481 | 12,466 (6.2) | 15 (5.6) | 0.061 | 60 | |

| Hemiplegia or paraplegia | 1489 | 1486 (0.7) | 3 (1.1) | 0.230 | 101 | |

| Renal disease | 3294 | 3292 (1.6) | 2 (0.7) | 0.439 | 30 | |

| End stage renal disease | 571 | 571 (0.3) | 0 (0) | - | 0 | |

| Osteoporosis | 30,314 | 30,286 (15) | 28 (10.4) | 0.232 | 46 |

| Variables | Categories | All | Patients Without Acute Transverse Myelitis (n = 201,500) | Patients with Acute Transverse Myelitis (n = 269) | Standardized Mean Difference | Incidence Rates (per 100,000 Person-Year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cervical surgery | All | 35,879 | 35,740 (17.7) | 139 (51.7) | 0.883 | 194 |

| Decompressive surgery | 21,260 | 21,175 (10.5) | 85 (31.6) | 200 | ||

| Fusion surgery | 14,619 | 14,565 (7.2) | 54 (20.1) | 185 | ||

| Thoracic surgery | All | 1904 | 1893 (0.9) | 11 (4.1) | 0.829 | 289 |

| Decompressive surgery | 1460 | 1454 (0.7) | 6 (2.2) | 205 | ||

| Fusion surgery | 444 | 439 (0.2) | 5 (1.9) | 563 | ||

| Lumbar surgery | All | 163,986 | 16,3867 (81.3) | 119 (44.2) | 0.939 | 36 |

| Decompressive surgery | 127,364 | 127,272 (63.2) | 92 (34.2) | 36 | ||

| Fusion surgery | 36,622 | 36,595 (18.2) | 27 (10) | 37 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kim, J.; Kim, T.-H. Incidence Rates and Diagnostic Trends of Perioperative Acute Transverse Myelitis in Patients Who Underwent Surgery for Degenerative Spinal Diseases: A Nationwide Epidemiologic Study of 201,769 Patients. Diagnostics 2026, 16, 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010015

Kim J, Kim T-H. Incidence Rates and Diagnostic Trends of Perioperative Acute Transverse Myelitis in Patients Who Underwent Surgery for Degenerative Spinal Diseases: A Nationwide Epidemiologic Study of 201,769 Patients. Diagnostics. 2026; 16(1):15. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010015

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Jihye, and Tae-Hwan Kim. 2026. "Incidence Rates and Diagnostic Trends of Perioperative Acute Transverse Myelitis in Patients Who Underwent Surgery for Degenerative Spinal Diseases: A Nationwide Epidemiologic Study of 201,769 Patients" Diagnostics 16, no. 1: 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010015

APA StyleKim, J., & Kim, T.-H. (2026). Incidence Rates and Diagnostic Trends of Perioperative Acute Transverse Myelitis in Patients Who Underwent Surgery for Degenerative Spinal Diseases: A Nationwide Epidemiologic Study of 201,769 Patients. Diagnostics, 16(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010015