Application of Telemedicine and Artificial Intelligence in Outpatient Cardiology Care: TeleAI-CVD Study (Design)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Artificial Intelligence in Management of Patients

- Substantial constraints limit AI adoption in clinical cardiology practice:

3. Telemedicine in Cardiology: Current Evidence and Best Practices

3.1. Hypertension: Home Blood Pressure Telemonitoring with Team-Based Management

3.2. Dyslipidemia and Integrated Cardiovascular Risk Management

3.3. Heart Failure: Remote Patient Management and Virtual Ward Models

3.4. Arrhythmias: Remote Rhythm Surveillance and Diagnostic Access

3.5. Cardiac Telerehabilitation and Secondary Prevention

3.6. Program Design Elements Driving Clinical Success

- Clinician-supervised therapeutic protocols. The strongest benefits are when telemonitoring couples with action authority—nurse/pharmacist-directed medication titration under protocolized guidelines, scheduled virtual consultations, and explicit physiologic thresholds triggering urgent evaluation [27].

- Validated devices and standardized training. Clinically validated monitors combined with structured patient training and periodic recalibration reduces signal noise and false-positive alerts [28].

- Engagement and adherence support infrastructure. Optimal programs incorporate automated reminders, intuitive interfaces, caregiver access, and multilingual materials; engagement decays without systematic reinforcement.

- Equity-centered design principles. Digital interventions demonstrate disparity-reduction potential when intentionally tailored through device provision, data plan subsidies, and culturally adapted content; without adaptations, programs risk exacerbating inequities.

- Data governance and health system integration. Secure transmission compliant with privacy regulations, role-based clinician access, and bidirectional EHR integration are essential for patient safety and workflow sustainability.

4. Integration of AI and Telemedicine: Synergistic Advantages and Implementation Challenges

4.1. Synergistic Advantages of AI-Enhanced Telemedicine

- Enhanced Clinical Surveillance Through Intelligent Monitoring. Traditional telemonitoring generates alert fatigue through crude threshold-based systems producing high false-positive rates. AI-enhanced systems employ multivariate pattern recognition, analyzing combinations of vital signs, symptoms, and temporal trends to identify clinically meaningful deterioration while filtering benign variations. A retrospective analysis of remote HF monitoring demonstrated that AI algorithms reduced false-positive alerts by 60% while improving sensitivity for detecting clinically significant decompensation from 71% to 89% compared to simple threshold alerts [29]. This intelligent surveillance enables proactive intervention before clinical crises materialize, shifting care paradigm from reactive crisis management to preventive optimization.

- Workflow Optimization and Documentation Efficiency. Telemedicine paradoxically increases the physician documentation burden: virtual consultations require identical charting to in-person visits, while reviewing transmitted monitoring data adds additional documentation requirements. AI-assisted documentation addresses this bottleneck through automated note generation, data summarization, and intelligent pre-charting. A prospective cohort study of AI documentation in 2500 virtual visits demonstrated a 43% reduction in physician documentation time (from 11.2 to 6.4 min per encounter) while maintaining note quality and completeness [30]. This efficiency gain is critical for telemedicine sustainability: without AI assistance, increased monitoring frequency threatens clinician burnout; with AI support, intensive monitoring becomes operationally feasible.

- Personalized Clinical Decision Support. The combination of continuous telemonitoring data and AI-driven analytics enables personalized risk stratification and treatment individualization impossible with episodic in-person assessment. Machine learning models trained on longitudinal patient-specific data can identify individual BP response patterns to medications, predict decompensation risk based on subtle trend changes unique to that patient, and optimize therapy timing based on circadian variation patterns [5]. This represents evolution from a population-based guideline application to genuine precision cardiovascular medicine.

- Patient Engagement and Adherence Enhancement. AI-powered chatbots and conversational interfaces integrated into telemedicine platforms provide 24/7 patient support, answering medication questions, delivering personalized educational content, and providing motivational coaching. A randomized trial of AI chatbot support integrated with BP telemonitoring demonstrated a 28% improvement in monitoring adherence and 31% improvement in medication adherence versus telemonitoring alone [31]. The AI system provided immediate feedback, celebratory messages for goal achievements, and gentle prompts for missed measurements, creating an engagement loop sustaining long-term participation.

4.2. Implementation Challenges and Mitigation Strategies

- Technical Integration and Interoperability. Integrating AI algorithms with existing EHR systems and telemonitoring platforms presents substantial technical challenges. Many healthcare institutions employ legacy EHR systems with limited API capabilities, necessitating costly custom integration work. Mitigation strategies include adopting HL7 FHIR standards for data exchange, employing middleware platforms facilitating EHR-agnostic connectivity, and leveraging cloud-based AI services, reducing on-premise computational requirements [32]. Our trial employs REDCap for research data capture interfacing with the STmedical telemedicine platform via standardized APIs, demonstrating feasibility of a modular integration approach.

- Clinical Validation and Regulatory Compliance. AI algorithms require rigorous clinical validation before deployment in patient care, yet regulatory frameworks for AI validation are still evolving. The FDA’s recently released guidance on clinical decision support software establishes a tiered risk classification determining regulatory oversight intensity [33]. Our trial addresses validation requirements through (1) pilot-testing AI algorithms on retrospective datasets before prospective deployment; (2) implementing mandatory physician oversight of all AI outputs; (3) systematic error tracking with pre-defined quality thresholds triggering algorithm retraining; and (4) comprehensive documentation of AI development methodology, training datasets, and performance metrics, enabling regulatory review.

- Clinician Training and Change Management. Successful AI–telemedicine implementation requires substantial clinician training encompassing both technical platform operation and conceptual understanding of AI capabilities and limitations. Physicians must learn when to trust AI recommendations and when to override them based on clinical judgment. Our trial employs a structured training program including didactic sessions on AI principles in cardiology (4 h), hands-on platform training with simulated patient cases (6 h), supervised initial consultations with feedback (first five real patient encounters), and ongoing continuing education addressing emerging challenges. Establishing physician “AI literacy” is a prerequisite for safe and effective implementation [34].

- Ethical Considerations and Patient Acceptance. Patients vary substantially in their comfort with AI involvement in their healthcare. Some view AI as an enhancement improving care quality; others express concerns about algorithmic bias, data privacy, or dehumanization of care. Transparent informed consent is essential, explicitly explaining AI’s role, acknowledging limitations, and emphasizing physician oversight. Our trial consent process includes an educational video demonstrating platform functionality, written materials addressing common concerns, and opt-out provisions allowing participation in telemedicine without AI features (patients would receive standard telehealth without AI documentation assistance). Preliminary survey data from our pilot phase indicated that 78% of patients expressed comfort with AI involvement after educational intervention, compared to 52% before education, highlighting the importance of transparent communication [35].

- Cost-Effectiveness and Sustainability. AI–telemedicine integration requires substantial upfront investment: platform licensing, hardware provision to patients, clinician training, and technical support infrastructure. Long-term sustainability depends on demonstrating favorable cost-effectiveness through reduced hospitalizations, decreased physician overtime, and improved patient outcomes justifying initial expenditure. Economic evaluation is an integral component of our trial, employing societal perspective and capturing costs across the healthcare system: intervention costs (devices, platform, and training), healthcare utilization costs (visits, hospitalizations, and testing), and productivity costs (patient work loss and caregiver burden). Break-even analysis will identify the threshold effect sizes necessary for cost-neutrality, informing future implementation decisions.

- Future Directions. Current systems position AI as a physician-assistive tool requiring human validation of all decisions. Future evolution may enable greater AI autonomy for routine tasks: automatic medication refills when adherence and BP control are stable, automated triage determining the urgency of physician review, and autonomous patient education delivery based on knowledge gaps identified through conversational analysis. However, autonomous AI decision-making introduces novel medicolegal questions regarding liability attribution when adverse outcomes occur. Regulatory frameworks must evolve alongside technological capabilities, balancing innovation enabling improved access and efficiency against safety imperatives, ensuring human oversight of high-stake clinical decisions. Our trial’s comprehensive safety monitoring and error tracking will generate evidence informing these policy discussions. The TeleAI-CVD trial represents the pragmatic integration of AI and telemedicine within contemporary care delivery constraints, prioritizing feasibility and safety while evaluating clinical effectiveness. By comprehensively documenting implementation challenges, workflow impacts, and patient outcomes, this trial will provide an evidence base guiding broader adoption of AI-enhanced telemedicine in cardiovascular care.

5. Ethical Framework for AI-Enhanced Cardiovascular Care

- Algorithmic Transparency and the “Black Box” Problem. Many contemporary AI systems, particularly deep learning models, function as “black boxes”, producing accurate predictions without providing interpretable reasoning. A cardiologist receives an AI alert, “High risk of HF hospitalization within 7 days (probability: 78%),” but cannot ascertain which specific data elements drove this prediction. This opacity creates ethical tension: physicians are held accountable for clinical decisions but cannot fully evaluate AI recommendations’ validity without understanding their derivation [36]. Explainable AI (XAI) methods attempt to address this through techniques like SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) values quantifying each variable’s contribution to predictions, attention maps highlighting which data elements the model weighted most heavily, and counterfactual explanations demonstrating which changes would alter the prediction [37]. Our trial employs rule-based algorithms for high-stake clinical alerts (explicitly programmed thresholds for BP, weight, and symptoms) ensuring complete transparency, while machine learning models are limited to lower-stake functions (pattern recognition in symptom narratives and trend visualization) where opacity carries less risk. This tiered approach balances AI’s analytical power against transparency requirements.

- Informed Consent and Patient Autonomy in AI-Assisted Care. Traditional informed consent addresses risks and benefits of medical interventions. AI integration requires expanded consent addressing the following: (1) explanation of AI’s role in care delivery—which tasks AI performs and which decisions remain exclusively physician-determined; (2) acknowledgment of AI limitations—potential for errors, inability to account for unique patient circumstances, and the ongoing learning nature of algorithms; (3) data usage disclosure—how patient data trains AI models, whether data is shared with AI vendors, and data retention and deletion policies; (4) alternative options—availability of care without AI involvement and the implications of opting out [38]. Our trial’s consent process employs a layered approach: a brief summary highlighting key points, a comprehensive detailed document for thorough review, an educational video demonstrating platform functionality, and an opportunity for questions with study coordinators. Patients uncomfortable with AI involvement can opt for standard telemedicine without AI documentation features, preserving autonomy while enabling study participation. This approach respects heterogeneous patient preferences regarding technology involvement in their care.

- Accountability and Liability in AI-Assisted Clinical Decisions. When adverse outcomes occur in AI-augmented care, liability attribution becomes complex. If an AI-generated summary omits critical information leading to inappropriate therapeutic decision, is the AI developer liable? The validating physician? The healthcare institution deploying the system? Existing medicolegal frameworks presume human decision-makers bear accountability, but AI’s increasing autonomy challenges this assumption [39]. Our trial design maintains clear accountability: physicians retain ultimate decision-making authority and bear professional responsibility for all clinical judgments. AI functions exclusively as an advisory tool; physicians can and should override AI recommendations when clinical judgment dictates. All AI-generated documentation undergoes mandatory physician review and approval, creating an explicit validation checkpoint. This human-in-the-loop design preserves the traditional accountability framework while enabling AI’s efficiency benefits. Documentation explicitly notes “AI-assisted” to ensure transparency in medical records. Errors attributable to AI are systematically tracked, triggering algorithm refinement and, if severe, a human factor review to determine if the user interface design contributed to misinterpretation.

- Data Privacy, Security, and Governance. AI systems require vast datasets for training and ongoing performance optimization. Patient data transmitted to cloud-based AI platforms raises privacy concerns: Who owns the data? Can it be used for purposes beyond the individual patient’s care? How long is it retained for? Can patients request data deletion? European GDPR establishes the “right to explanation” for automated decisions and “right to erasure,” but practical implementation in healthcare contexts remains challenging given legitimate needs for long-term medical records and AI model training [40]. Our trial implements a comprehensive data governance framework: (1) data minimization—collecting only data necessary for clinical care and research objectives; (2) purpose limitation—data used exclusively for trial purposes, not for unrelated AI model development; (3) encryption at rest and in transit—256-bit AES encryption for stored data and TLS 1.3 for transmission; (4) access controls—role-based permissions limiting data access to authorized personnel; (5) audit trails—logging all data access and modification; (6) data retention policies—anonymized research data retained per regulatory requirements and identifiable clinical data deleted per institutional policies post-trial; (7) patient data access—participants can review their data and request corrections to factual errors.

- Algorithmic Bias and Health Equity. AI algorithms trained predominantly on data from majority populations may perform poorly in underrepresented groups, potentially exacerbating existing health disparities. Studies have demonstrated racial bias in algorithms predicting healthcare utilization, with models systematically underestimating illness severity in Black patients versus White patients with an equivalent objective health status [41]. Similar concerns exist for sex, age, and socioeconomic biases. Mitigation strategies include (1) diverse training datasets—ensuring AI models are trained on representative patient populations; (2) bias testing—systematically evaluating algorithm performance across demographic subgroups; (3) continuous monitoring—tracking outcome disparities during deployment; and (4) transparency—publicly reporting performance metrics stratified by patient characteristics [42]. Our trial employs stratified randomization, ensuring a balanced demographic distribution, with pre-planned subgroup analyses by age, sex, and disease category to detect differential AI performance. If significant disparities emerge, algorithms will undergo retraining with oversampling of underperforming subgroups.

- Justice and Equitable Access to AI-Enhanced Care. Technology-dependent care delivery risks creating a “digital divide” where vulnerable populations lacking smartphones, reliable internet, or technical literacy are excluded from innovative interventions. Paradoxically, these populations often have the highest cardiovascular disease burden and would benefit most from intensive monitoring. Equity-conscious implementation requires proactive measures: device provision programs for patients lacking hardware, subsidized data plans for those unable to afford connectivity, multilingual interfaces accommodating linguistic diversity, simplified interfaces for low health-literacy populations, and alternative options for those preferring traditional care models [43]. Our trial explicitly addresses equity through (1) universal device provision—all intervention patients receive the necessary hardware regardless of their ability to purchase it; (2) connectivity support—mobile hotspots provided for patients lacking home internet; (3) caregiver-assisted protocols—allowing family members to assist with technology operation for patients with physical or cognitive limitations; (4) a multilingual platform—supporting Slovak, English, and Hungarian, reflecting regional linguistic diversity; (5) variable-intensity support—more intensive training and technical support for patients with lower baseline technical literacy. Post-trial, we will evaluate intervention effectiveness across socioeconomic strata to determine whether AI–telemedicine reduces, maintains, or exacerbates disparities.

- Professional Integrity and the Human Element in Medicine. Concerns persist that AI-augmented care may erode physician–patient relationships, replacing empathetic human connection with algorithmic efficiency. Patients may feel their concerns are filtered through AI rather than receiving a physician’s undivided attention. Physicians may become overly reliant on AI recommendations, diminishing clinical reasoning skills through atrophy [44]. A counter-argument emphasizes that by automating routine tasks—data synthesis, documentation, and guideline checking—AI liberates physician time and cognitive resources for genuinely human elements of medicine: empathetic listening, nuanced counseling, and shared decision-making incorporating patient values. Empirical evidence from AI documentation studies demonstrates that physicians using ambient AI scribes report improved eye contact with patients and enhanced perception of physician attentiveness [45]. Rather than replacing human connection, well-designed AI systems may enhance it by reducing distracting administrative burdens. Our trial evaluates this dimension through validated patient satisfaction measures assessing perceived physician empathy, time feeling heard, and satisfaction with communication. We hypothesize that AI-enabled workflow efficiency will enhance rather than diminish relational quality by allowing physicians to focus on patient interaction rather than documentation during consultations.

6. Materials and Methods

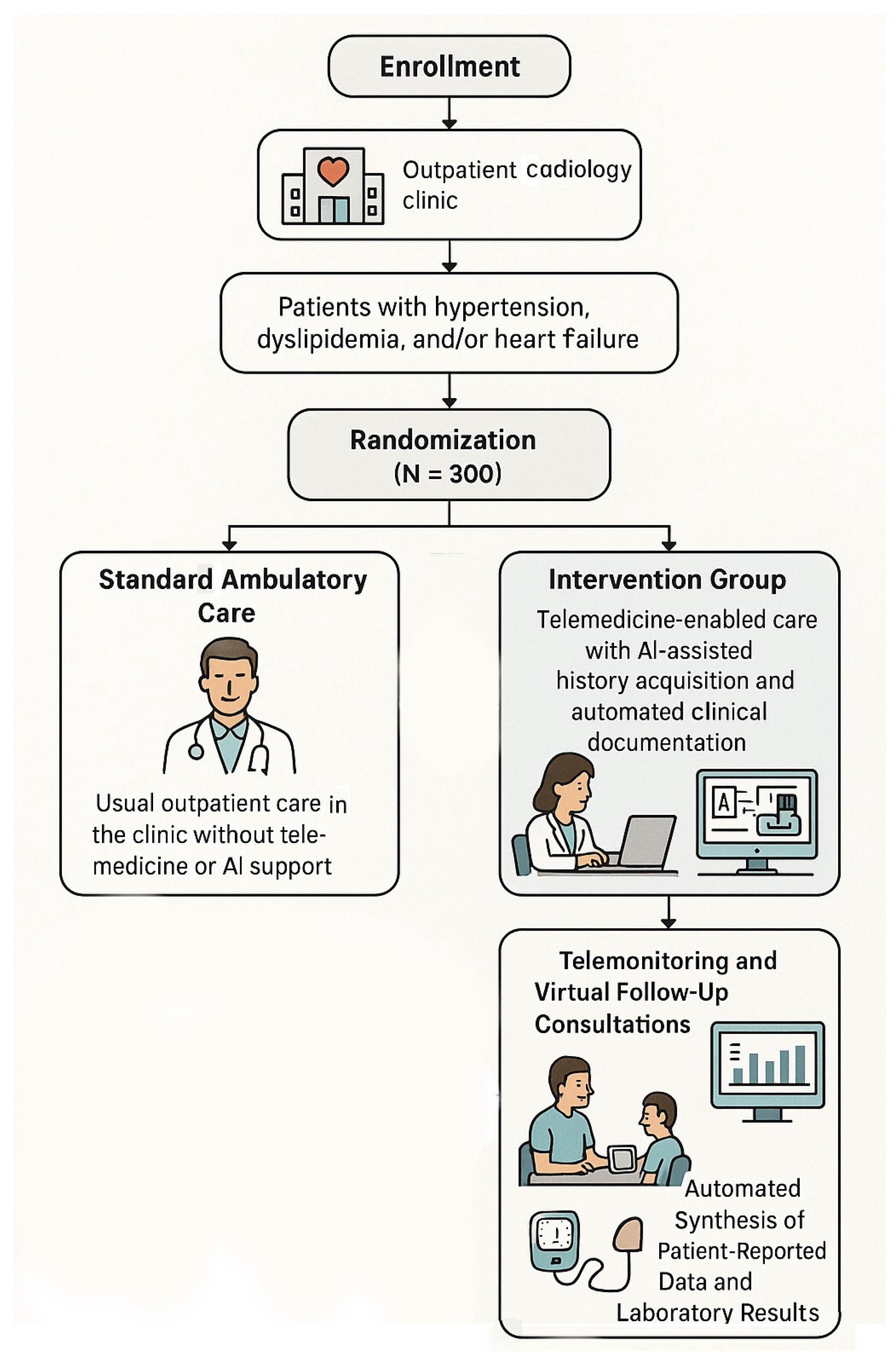

6.1. Study Design

6.2. Patient Population and Eligibility Criteria

6.3. Randomization and Blinding Procedures

- Objective outcome measures—blood pressure measurements using validated automated devices and laboratory parameters analyzed by a blinded central laboratory;

- Identical clinical personnel across arms—delivering guideline-based care;

- Blinded adjudication of clinical endpoints—hospitalizations and major adverse cardiovascular events) by independent reviewers using standardized criteria;

- Blinded statistical analysis—using coded identifiers, with unmasking only after primary analysis completion;

- Standardized data collection protocols—with structured case report forms to minimize measurement bias;

- Independent data monitoring—by personnel not involved in patient care.

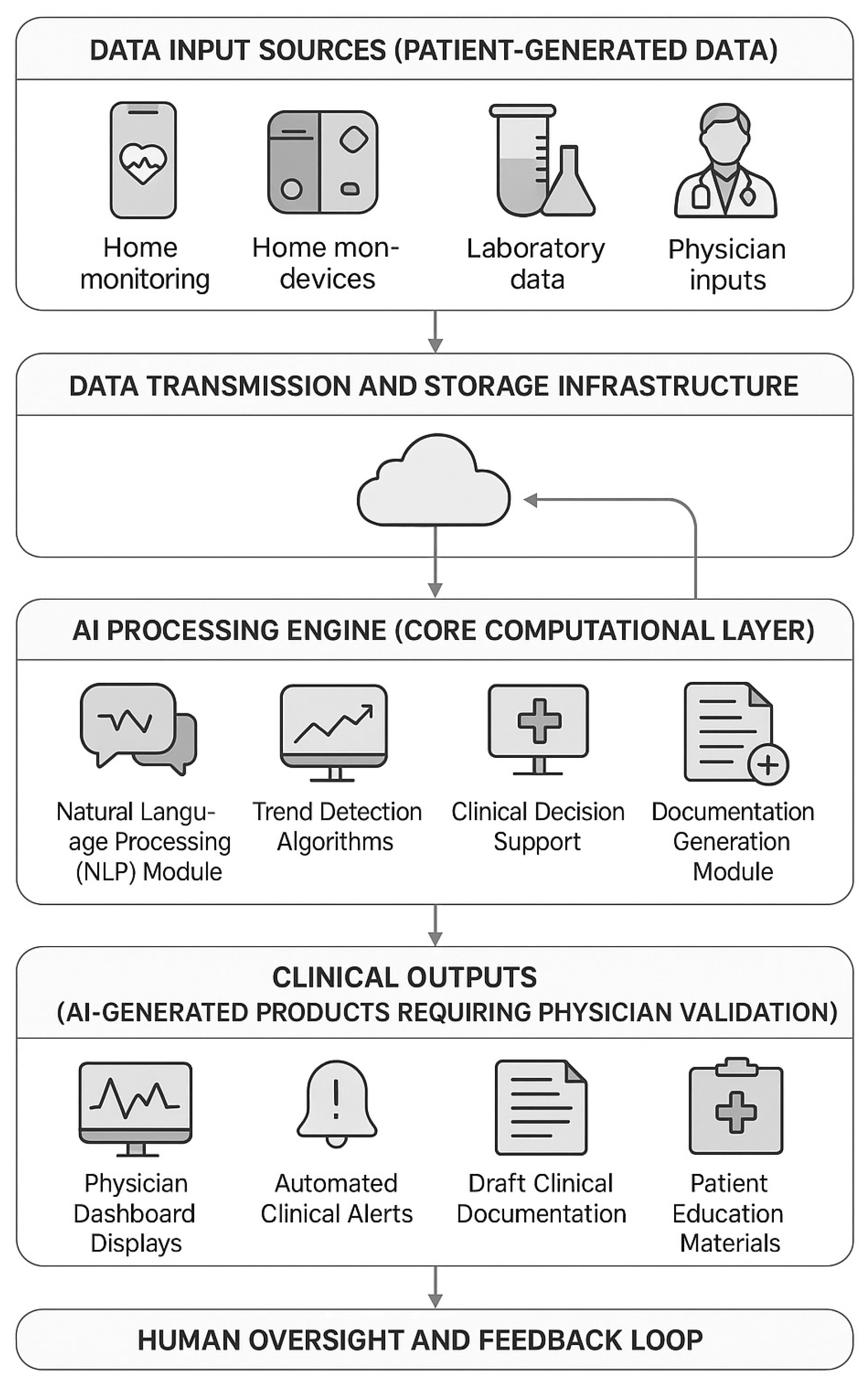

6.4. Processing and Availability of Data

- Blood Pressure Monitoring:

- Device: Omron Evolv (model BP7000) or equivalent validated oscillometric device.

- Validation: Meets ESH International Protocol and AAMI standards.

- Calibration: Annual calibration verification; replaced if accuracy drift detected.

- Transmission: Automatic Bluetooth pairing with STmedical mobile application.

- Training: In-person demonstration with return demonstration; written instructions provided.

- Measurement protocol: Seated position, 5 min rest, arm supported at heart level, 2 measurements 1 min apart.

- Weight Monitoring (Heart Failure Patients):

- Device: Withings Body+ or equivalent with 0.1 kg precision.

- Validation: Verified against calibrated clinic scale at baseline.

- Transmission: Wi-Fi-enabled automatic data upload.

- Measurement protocol: Daily morning measurement, same time, after voiding, minimal clothing.

- Point-of-Care Laboratory Testing:

- Lipid panels: Venipuncture at certified laboratories with results uploaded to the platform via secure HL7 integration.

- NT-proBNP (HF patients): Obtained at protocol timepoints (baseline, 6, and 12 months).

- Electrolytes and renal function: Standard laboratory testing per protocol.

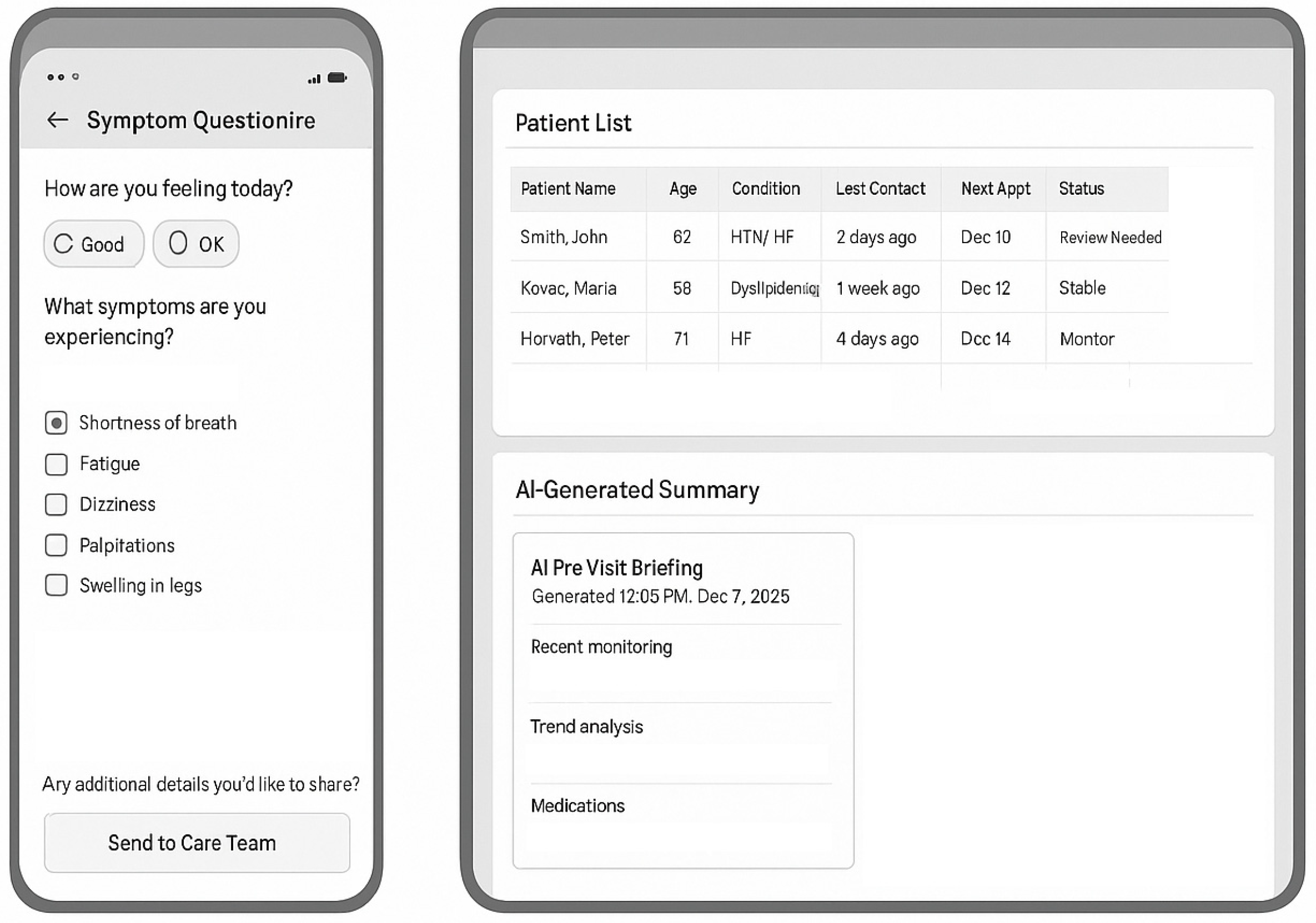

- Mobile Application (STmedical Platform) (Figure 2):

- Compatibility: iOS 13+ and Android 9+; tablets provided to patients without compatible devices.

- Features:

- ▪

- Real-time vital sign display with trend graphs.

- ▪

- Symptom questionnaire interface.

- ▪

- Medication tracker with reminders.

- ▪

- Secure messaging with care team.

- ▪

- Video consultation interface (HIPAA-compliant, 256-bit encryption).

- ▪

- Educational content library.

- ▪

- Technical Support: 24/7 helpline; average response time < 2 h; in-person troubleshooting available.

- Internet Connectivity Support:

- Patients lacking adequate home internet receive mobile hotspot devices (4G LTE).

- Data costs covered by study budget.

- Backup plan: telephone-based data reporting for technical failures.

- Quality Control Measures:

- Monthly automated device functionality checks.

- Quarterly patient-reported device performance surveys.

- Replacement devices provided within 24 h for malfunctions.

- Data transmission failures trigger automatic alerts to study coordinators.

- Structural Virtual Follow-Up Consultation Protocol

- Pre-Consultation Preparation (48 h before appointment):

- Automated Patient Reminders: SMS and app notifications with appointment details.

- Pre-Visit Questionnaire Deployment:

- (a)

- Symptom Assessment Module

- Chest pain/discomfort (character, frequency, triggers, and duration).

- Dyspnea assessment (NYHA class screening questions and exertional limitations).

- Palpitations, syncope, and presyncope episodes.

- Lower extremity edema (visual analog scale + photo upload option).

- Fatigue/functional capacity changes.

- (b)

- Medication Adherence Module:

- Morisky-8 scale automated scoring.

- Missed dose quantification.

- Side effect reporting (structured checklist).

- Medication access barriers.

- (c)

- Disease-Specific Modules:

- Hypertension: Headaches, visual changes, and recent BP readings.

- Heart Failure: Weight trajectory, orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, and exercise tolerance.

- Dyslipidemia: Muscle symptoms (statin-related myalgia screening).

- (d)

- Lifestyle Factors: Diet adherence, physical activity minutes/week, smoking status, and alcohol intake.

- AI-generated pre-visit summary (created 24 h before consultation):

- Synthesizes telemonitoring data from the preceding 2 weeks.

- Flags abnormal trends (BP elevations, weight gain, and declining data transmission).

- Compares current vs. previous visit parameters.

- Integrates recent laboratory results.

- Highlights patient-reported concerns requiring discussion.

- Generates a preliminary assessment and suggested discussion topics.

- Virtual Consultation Structure (20–30 min duration):

- Phase 1: Rapport and Technical Check (2–3 min)

- Video/audio quality verification.

- Privacy confirmation (patient in confidential space).

- Agenda setting.

- Phase 2: Symptom Review (5–7 min)

- Physician reviews AI-generated symptom summary.

- Clarifies concerning responses from questionnaire.

- Conducts focused history relevant to patient-reported changes.

- Visual assessment when appropriate (edema and respiratory effort).

- Phase 3: Data Review and Interpretation (8–10 min)

- Review telemonitoring trends displayed on shared screen:

- ▪

- BP trend graphs with target zone overlay.

- ▪

- Weight trajectory (HF patients).

- ▪

- Measurement frequency and timing patterns.

- Laboratory result interpretation:

- ▪

- Comparison to previous values and guideline targets.

- ▪

- Discussion of clinical significance.

- AI-generated interpretation presented with physician commentary

- Phase 4: Therapeutic Decision-Making (5–8 min)

- Assessment of current therapy effectiveness.

- Medication adjustments when indicated:

- ▪

- Hypertension: Dose titration or additional agent per JNC-8/ESC guidelines.

- ▪

- Heart Failure: GDMT optimization per ESC guidelines.

- ▪

- Dyslipidemia: Statin intensity adjustment, ezetimibe/PCSK9i consideration.

- Prescriptions transmitted electronically.

- Rationale explanation and shared decision-making.

- Phase 5: Patient Education and Action Plan (3–5 min)

- Reinforcement of monitoring protocol.

- Lifestyle modification counseling.

- Symptom red flags requiring urgent contact.

- Next appointment scheduling.

- Opportunity for patient questions.

- Phase 6: Documentation (Physician workflow)

- Review of AI-generated encounter note draft.

- Physician edits, additions, and approval.

- Finalization in HER.

- Patient receives visit summary via app within 2 h.

- Standardized Clinical Decision Support Algorithms Embedded in Consultation:

- Hypertension Management Algorithm:

- If average home BP ≥ 135/85 mmHg over 2 weeks:

- ▪

- Stage 1: Medication adherence review → lifestyle counseling intensification → consider dose increase.

- ▪

- Stage 2: Add second agent from complementary class per ESC algorithm.

- ▪

- Stage 3: Specialist referral for resistant hypertension.

- Heart Failure Management Algorithm:

- If weight increase >2 kg in 3 days or worsening symptoms:

- ▪

- Assess volume status markers (orthopnea, edema, and BP trends).

- ▪

- Diuretic adjustment (dose increase or additional agent).

- ▪

- Consider urgent in-person visit or telehealth-guided clinic visit.

- ▪

- NT-proBNP measurement if not recently obtained.

- GDMT optimization pathway:

- ▪

- Systematic review of ACEi/ARB/ARNI, beta-blocker, and MRA status.

- ▪

- Dose titration schedule per ESC recommendations.

- ▪

- SGLT2i initiation if not contraindicated.

- Dyslipidemia Management Algorithm:

- Risk stratification (ESC/EAS 2019 algorithm).

- LDL-C target determination.

- Intensification pathway:

- ▪

- Maximize statin (with safety monitoring).

- ▪

- Add ezetimibe if target not achieved.

- ▪

- Consider PCSK9i for very high-risk patients.

- Triggers for Unscheduled In-Person Evaluation:

- New/worsening chest pain or dyspnea at rest.

- Syncope or presyncope.

- Sustained BP >180/110 mmHg with symptoms.

- Weight gain >3 kg in 5 days despite diuretic adjustment.

- Patient/physician concern requiring physical examination.

- Quality Assurance Measures:

- 10% of consultations randomly recorded (with consent) for quality review.

- Quarterly physician peer review sessions.

- Patient satisfaction survey after each visit (5-item scale).

- Technical quality metrics (connection failures and audio/video issues) tracked.

- Consultation duration monitoring to ensure adequate time allocation.

- Hypertension: 35% achieving BP <130/80 mmHg.

- Dyslipidemia: 40% achieving individualized LDL-C targets.

- Heart failure: 50% achieving composite endpoint (no HF hospitalization + maintained/improved NYHA class).

- 1.

- Initial On-Site Consultation with AI-Assisted History Acquisition and Documentation

- 2.

- Telemonitoring and Virtual Follow-Up Consultations

- 3.

- Automated Synthesis of Patient-Reported Data and Laboratory Results

6.5. Control Group: Standard Ambulatory Care

6.6. Outcomes

6.7. Data Collection Procedures

6.7.1. Data Management

6.7.2. Data Quality Assurance

6.7.3. Statistical Analysis Plan

6.8. Feasibility and Implementation

- Established infrastructure: Existing outpatient cardiology clinics with electronic health record systems, trained clinical staff, and patient population.

- Validated technology platform: STmedical telemedicine platform with proven functionality in clinical settings and an integrated AI documentation system with preliminary validation.

- Regulatory approvals: Ethics committee approval obtained (IRB/ERC of the Kosice Self-Governing Region, Reference number 9483/2025/ODDZ-48993).

- Funding secured: Grant VEGA 1/0700/23 provides financial support for study conduct.

- Operational readiness: Standard operating procedures developed, staff training completed, and device procurement arranged.

6.9. Timeline

7. Results and Discussion

- Clinical efficacy: Greater reductions in BP (estimated 5–10 mmHg additional systolic BP reduction), larger improvements in lipid parameters (estimated 15–20 mg/dL additional LDL-C reduction), and reduced HF hospitalization rates (estimated 30–40% relative reduction).

- Patient experience: Higher satisfaction scores, improved quality of life, and better medication adherence in the intervention group.

- Physician experience: Reduced documentation burden (estimated 20–30% reduction in time per patient), decreased burnout scores, and improved work–life balance despite increased patient monitoring intensity.

- Safety profile: Comparable or improved safety outcomes with no increase in adverse events, with potential for earlier detection and intervention for clinical deterioration.

- Healthcare utilization: Reduced total healthcare utilization despite increased virtual encounters, with particular reductions in emergency department visits and hospitalizations.

- Evidence base—for AI-enhanced telemedicine in cardiovascular care.

- Operational framework—for implementation in other healthcare settings.

- Health economic data—to inform healthcare policy and reimbursement decisions.

- Foundation—for future multi-center trials and broader implementation.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Böhm, M.; Burri, H.; Butler, J.; Čelutkienė, J.; Chioncel, O.; et al. 2023 Focused Update of the 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 3627–3639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehler, F.; Koehler, K.; Deckwart, O.; Prescher, S.; Wegscheider, K.; Kirwan, B.-A.; Winkler, S.; Vettorazzi, E.; Bruch, L.; Oeff, M.; et al. Efficacy of telemedical interventional management in patients with heart failure (TIM-HF2): A randomised, controlled, parallel-group, unmasked trial. Lancet 2018, 392, 1047–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolis, K.L.; Asche, S.E.; Bergdall, A.R.; Dehmer, S.P.; Groen, S.E.; Kadrmas, H.M.; Kerby, T.J.; Klotzle, K.J.; Maciosek, M.V.; Michels, R.D. Effect of home blood pressure telemonitoring and pharmacist management on blood pressure control: A cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2013, 310, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai-Seale, M.; Olson, C.W.; Li, J.; Chan, A.S.; Morikawa, C.; Durbin, M.; Wang, W.; Luft, H.S. Electronic Health Record Logs Indicate That Physicians Split Time Evenly Between Seeing Patients and Desktop Medicine. Health Aff. 2017, 36, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, S.J.; Devon-Sand, A.; Ma, S.P.; Jeong, Y.; Crowell, T.; Smith, M.; Liang, A.S.; Delahaie, C.; Hsia, C.; Shanafelt, T.; et al. Ambient artificial intelligence scribes: Physician burnout and perspectives on usability and documentation burden. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2025, 32, 375–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Zou, H.; Wu, L.; Dong, P.; Yuan, W.; Chen, Y. Generative artificial intelligence in cardiovascular specialty care: A scoping review. BMC Nurs. 2025, 24, 947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biondi-Zoccai, G.; D’Ascenzo, F.; Giordano, S.; Mirzoyev, U.; Erol, Ç.; Cenciarelli, S.; Leone, P.; Versaci, F. Artificial Intelligence in Cardiology: General Perspectives and Focus on Interventional Cardiology. Anatol. J. Cardiol. 2025, 29, 152–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, D.; He, B.; Ghorbani, A.; Yuan, N.; Ebinger, J.; Langlotz, C.P.; Heidenreich, P.A.; Harrington, R.A.; Liang, D.H.; Ashley, E.A.; et al. Video-based AI for beat-to-beat assessment of cardiac function. Nature 2020, 580, 252–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Gajjala, S.; Agrawal, P.; Tison, G.H.; Hallock, L.A.; Beussink-Nelson, L.; Lassen, M.H.; Fan, E.; Aras, M.A.; Jordan, C.; et al. Fully Automated Echocardiogram Interpretation in Clinical Practice. Circulation 2018, 138, 1623–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendt, S.J.; Dinh, C.T.; Sutcliffe, M.; Jones, K.; Scanlan, J.M.; Smitherman, J.S. Deploying ambient clinical intelligence to improve care: A research article assessing the impact of nuance DAX on documentation burden and burnout. Future Health J. 2025, 12, 100450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, V.L.; Shortliffe, E.H.; Stefanelli, M.; Szolovits, P.; Berthold, M.R.; Bellazzi, R.; Abu-Hanna, A. The coming of age of artificial intelligence in medicine. Artif. Intell. Med. 2009, 46, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayers, J.W.; Poliak, A.; Dredze, M.; Leas, E.C.; Zhu, Z.; Kelley, J.B.; Faix, D.J.; Goodman, A.M.; Longhurst, C.A.; Hogarth, M.; et al. Comparing Physician and Artificial Intelligence Chatbot Responses to Patient Questions Posted to a Public Social Media Forum. JAMA Intern. Med. 2023, 183, 589–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozyel, S.; Şimşek, E.; Koçyiğit Burunkaya, D.; Güler, A.; Korkmaz, Y.; Şeker, M.; Ertürk, M.; Keser, N. Artificial Intelligence-Based Clinical Decision Support Systems in Cardiovascular Diseases. Anatol. J. Cardiol. 2024, 28, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boima, V.; Doku, A.; Agyekum, F.; Tuglo, L.S.; Agyemang, C. Effectiveness of digital health interventions on blood pressure control, lifestyle behaviours and adherence to medication in patients with hypertension in low-income and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. EClinicalMedicine 2024, 69, 102432. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mahdavi, M.; Kazemnejad, A.; Asosheh, A.; Khalili, D. Cardiovascular risk patterns through AI-enhanced clustering of longitudinal health data. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 2025, 24, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zondag, A.G.M.; Rozestraten, R.; Grimmelikhuijsen, S.G.; Jongsma, K.R.; van Solinge, W.W.; Bots, M.L.; Vernooij, R.W.M.; Haitjema, S. The Effect of Artificial Intelligence on Patient-Physician Trust: Cross-Sectional Vignette Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2024, 26, e50853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.I.; Shih, L.C.; Kolachalama, V.B. Machine Learning in Clinical Trials: A Primer with Applications to Neurology. Neurotherapeutics 2023, 20, 1066–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, W.W.; Bai, Y.Y.; Yan, L.; Zheng, W.; Zeng, Q.; Zheng, Y.S.; Zha, L.; PI, H.Y.; Sai, X.Y. Effect of Home Blood Pressure Telemonitoring Plus Additional Support on Blood Pressure Control: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 2023, 36, 517–526. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, M.E.; Mszar, R.; Grimshaw, A.A.; Gunderson, C.G.; Onuma, O.K.; Lu, Y.; Spatz, E.S. Digital Health Interventions for Hypertension Management in US Populations Experiencing Health Disparities: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2356070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogedegbe, G.; Teresi, J.A.; Williams, S.K.; Ogunlade, A.; Izeogu, C.; Eimicke, J.P.; Kong, J.; Silver, S.A.; Williams, O.; Valsamis, H. Home Blood Pressure Telemonitoring and Nurse Case Management in Black and Hispanic Patients with Stroke: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2024, 332, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowie, M.R.; Lam, C.S.P. Remote monitoring and digital health tools in CVD management. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2021, 18, 457–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankaranarayanan, R.; Rasoul, D.; Murphy, N.; Kelly, A.; Nyjo, S.; Jackson, C.; O’COnnor, J.; Almond, P.; Jose, N.; West, J.; et al. Telehealth-aided outpatient management of acute heart failure in a specialist virtual ward compared with standard care. ESC Heart Fail. 2024, 11, 4172–4184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planinc, I.; Milicic, D.; Cikes, M. Telemonitoring in Heart Failure Management. Card Fail. Rev. 2020, 6, e06. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Chen, Y.; Lane, D.A.; Liu, L.; Wang, Y.; Lip, G.Y.H. Mobile Health Technology for Atrial Fibrillation Management Integrating Decision Support, Education, and Patient Involvement: mAF App Trial. Am. J. Med. 2017, 130, 1388–1396.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasitlumkum, N.; Cheungpasitporn, W.; Chokesuwattanaskul, A.; Thangjui, S.; Thongprayoon, C.; Bathini, T.; Vallabhajosyula, S.; Kanitsoraphan, C.; Leesutipornchai, T.; Chokesuwattanaskul, R. Diagnostic accuracy of smart gadgets/wearable devices in detecting atrial fibrillation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2021, 114, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meslet, J.B.; Dugué, B.; Brisset, U.; Pianeta, A.; Kubas, S. Evaluation of a Hybrid Cardiovascular Rehabilitation Program in Acute Coronary Syndrome Low-Risk Patients Organised in Both Cardiac Rehabilitation and Sport Centres: A Model Feasibility Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stergiou, G.S.; Alpert, B.S.; Mieke, S.; Wang, J.; O’Brien, E. Validation protocols for blood pressure measuring devices in the 21st century. J. Clin. Hypertens. 2018, 20, 1096–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajeu, G.S.; Ruiz-Negrón, N.; Moran, A.E.; Zhang, Z.; Kolm, P.; Weintraub, W.S.; Bress, A.P.; Bellows, B.K. Cost of Cardiovascular Disease Event and Cardiovascular Disease Treatment-Related Complication Hospitalizations in the United States. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2024, 17, e009999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinrichs, N.; Meyer, A.; Koehler, K.; Kaas, T.; Hiddemann, M.; Spethmann, S.; Balzer, F.; Eickhoff, C.; Falk, V.; Hindricks, G.; et al. Artificial intelligence based real-time prediction of imminent heart failure hospitalisation in patients undergoing non-invasive telemedicine. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2024, 11, 1457995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tierney, A.; Gayre, G.; Hoberman, B.; Mattern, B.; Ballesca, M.; Hannay, S.B.W.; Castilla, K.; Lau, C.S.; Kipnis, P.; Liu, V.; et al. Ambient Artificial Intelligence Scribes: Learnings after 1 Year and over 2.5 Million Uses. NEJM Catal. Innov. Care Deliv. 2025, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukac, P.J.; Turner, W.; Vangala, S.; Jeong, Y.; Crowell, T.; Smith, M.; Liang, A.S.; Delahaie, C.; Hsia, C.; Shanafelt, T.; et al. Ambient AI Scribes in Clinical Practice: A Randomized Trial. NEJM AI 2025, 2, AIoa2501000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandel, J.C.; Kreda, D.A.; Mandl, K.D.; Kohane, I.S.; Ramoni, R.B. SMART on FHIR: A standards-based, interoperable apps platform for electronic health records. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2016, 23, 899–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Food and Drug Administration. Clinical Decision Support Software: Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff; US Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Paranjape, K.; Schinkel, M.; Nannan Panday, R.; Car, J.; Nanayakkara, P. Introducing artificial intelligence training in medical education. JMIR Med. Educ. 2019, 5, e16048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Hoek, J.; Huber, A.; Leichtle, A.; Härmä, K.; Hilt, D.; von Tengg-Kobligk, H.; Poellinger, A. A survey on the future of radiology among radiologists, medical students and surgeons: Students and surgeons tend to be more skeptical about artificial intelligence and radiologists may fear that other disciplines take over. Eur. J. Radiol. 2019, 121, 108742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzinger, A.; Biemann, C.; Pattichis, C.S.; Kell, D.B. What do we need to build explainable AI systems for the medical domain? arXiv 2017, arXiv:1712.09923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Nair, B.; Vavilala, M.S.; Horibe, M.; Eisses, M.J.; Adams, T.; Liston, D.E.; Low, D.K.-W.; Newman, S.-F.; Kim, J.; et al. Explainable machine-learning predictions for the prevention of hypoxaemia during surgery. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2018, 2, 749–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerke, S.; Minssen, T.; Cohen, G. Ethical and legal challenges of artificial intelligence-driven healthcare. In Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Price, W.N., II; Gerke, S.; Cohen, I.G. Potential liability for physicians using artificial intelligence. JAMA 2019, 322, 1765–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vayena, E.; Blasimme, A.; Cohen, I.G. Machine learning in medicine: Addressing ethical challenges. PLoS Med. 2018, 15, e1002689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obermeyer, Z.; Powers, B.; Vogeli, C.; Mullainathan, S. Dissecting racial bias in an algorithm used to manage the health of populations. Science 2019, 366, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Char, D.S.; Shah, N.H.; Magnus, D. Implementing machine learning in health care—Addressing ethical challenges. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 981–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, K.; Calo, R. There is a blind spot in AI research. Nature 2016, 538, 311–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabitza, F.; Rasoini, R.; Gensini, G.F. Unintended consequences of machine learning in medicine. JAMA 2017, 318, 517–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kueper, J.K.; Terry, A.L.; Zwarenstein, M.; Lizotte, D.J. Artificial intelligence and primary care research: A scoping review. Ann. Fam. Med. 2020, 18, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | Target Distribution | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Total sample size | 300 patients (150 per group) | Powered for 20% absolute difference in primary endpoint |

| Disease distribution | Stratified randomization | |

| 35% (n = 105) | Largest ambulatory cardiology population |

| 25% (n = 75) | Common isolated condition |

| 20% (n = 60) | High-risk, resource-intensive |

| 20% (n = 60) | Reflects real-world comorbidity |

| Age distribution | Representative of ambulatory cardiology | |

| 40% (n = 120) | Working-age population |

| 60% (n = 180) | Higher CVD prevalence |

| Sex distribution | Target equal representation | |

| 50% (n = 150) | |

| 50% (n = 150) | |

| Technology literacy | Inclusion criterion | |

| 70% (n = 210) | Facilitates adoption |

| 30% (n = 90) | Maintains equity |

| Baseline control status | Enrichment for intervention benefit | |

| 70% (n = 210) | Primary target population |

| 30% (n = 90) | Prevention focus |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Toth, S.; Barbierik Vachalcova, M.; Barbierik, K.; Jarolimkova, A.; Fulop, P.; Dvoroznakova, M.; Pella, D.; Poruban, T. Application of Telemedicine and Artificial Intelligence in Outpatient Cardiology Care: TeleAI-CVD Study (Design). Diagnostics 2026, 16, 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010145

Toth S, Barbierik Vachalcova M, Barbierik K, Jarolimkova A, Fulop P, Dvoroznakova M, Pella D, Poruban T. Application of Telemedicine and Artificial Intelligence in Outpatient Cardiology Care: TeleAI-CVD Study (Design). Diagnostics. 2026; 16(1):145. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010145

Chicago/Turabian StyleToth, Stefan, Marianna Barbierik Vachalcova, Kamil Barbierik, Adriana Jarolimkova, Pavol Fulop, Mariana Dvoroznakova, Dominik Pella, and Tibor Poruban. 2026. "Application of Telemedicine and Artificial Intelligence in Outpatient Cardiology Care: TeleAI-CVD Study (Design)" Diagnostics 16, no. 1: 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010145

APA StyleToth, S., Barbierik Vachalcova, M., Barbierik, K., Jarolimkova, A., Fulop, P., Dvoroznakova, M., Pella, D., & Poruban, T. (2026). Application of Telemedicine and Artificial Intelligence in Outpatient Cardiology Care: TeleAI-CVD Study (Design). Diagnostics, 16(1), 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010145