Vertebral Metastasis in a Bronchial Carcinoid: A Rare Case Report with More than 3-Year Follow-Up and Review of the Literature

Abstract

1. Introduction

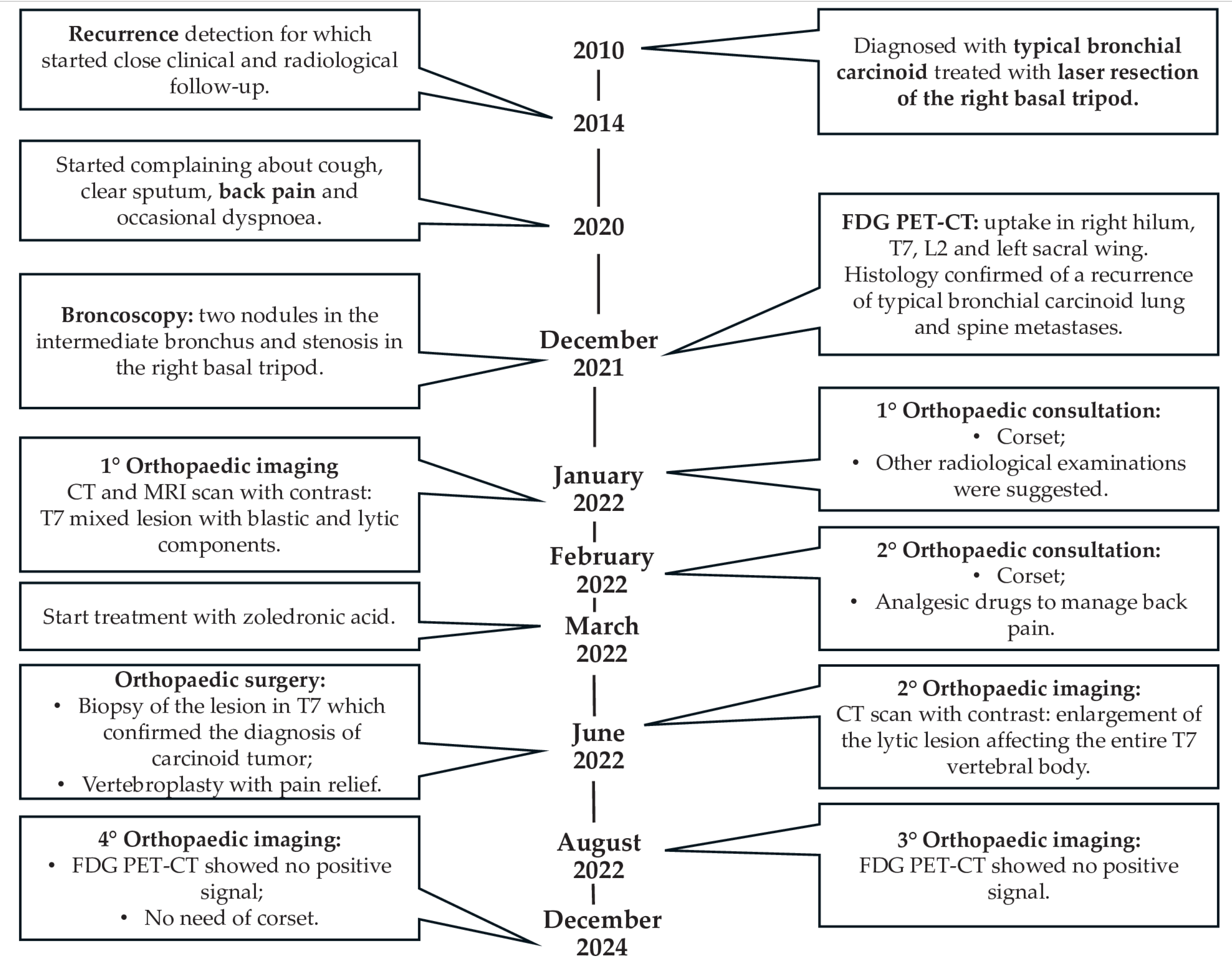

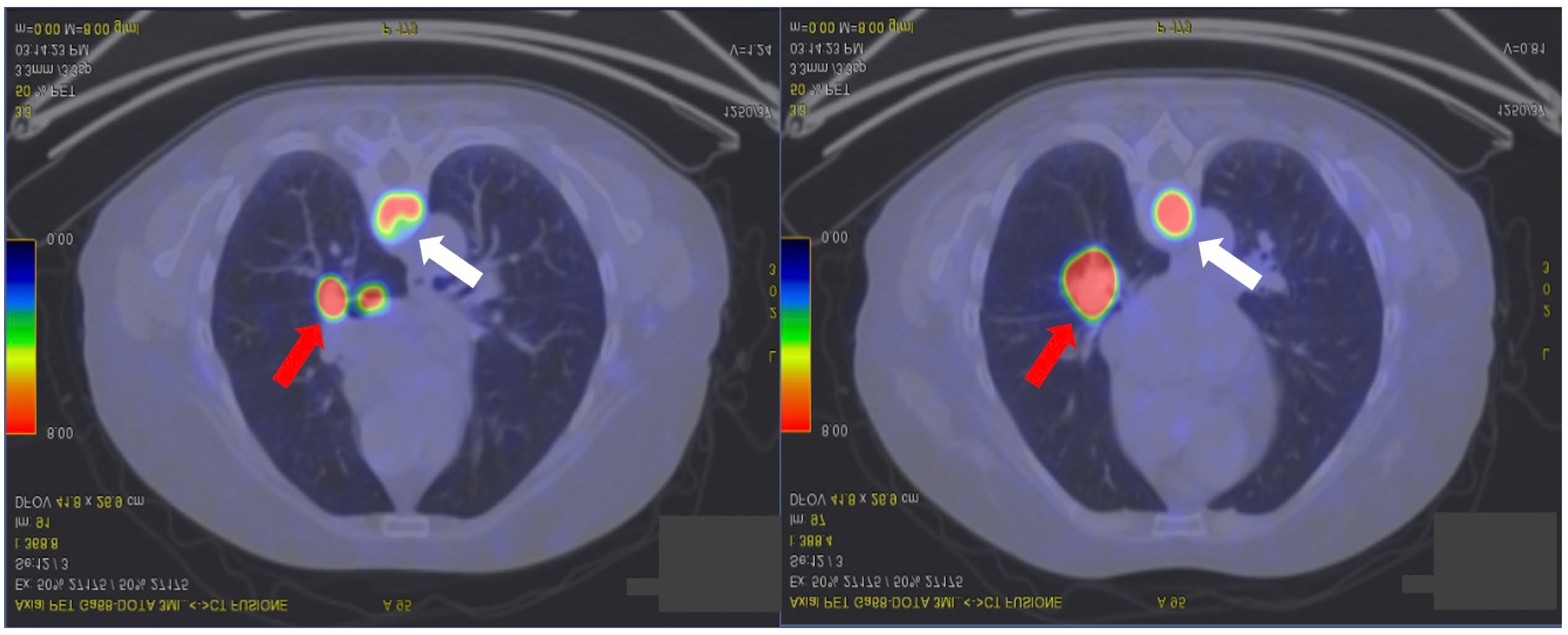

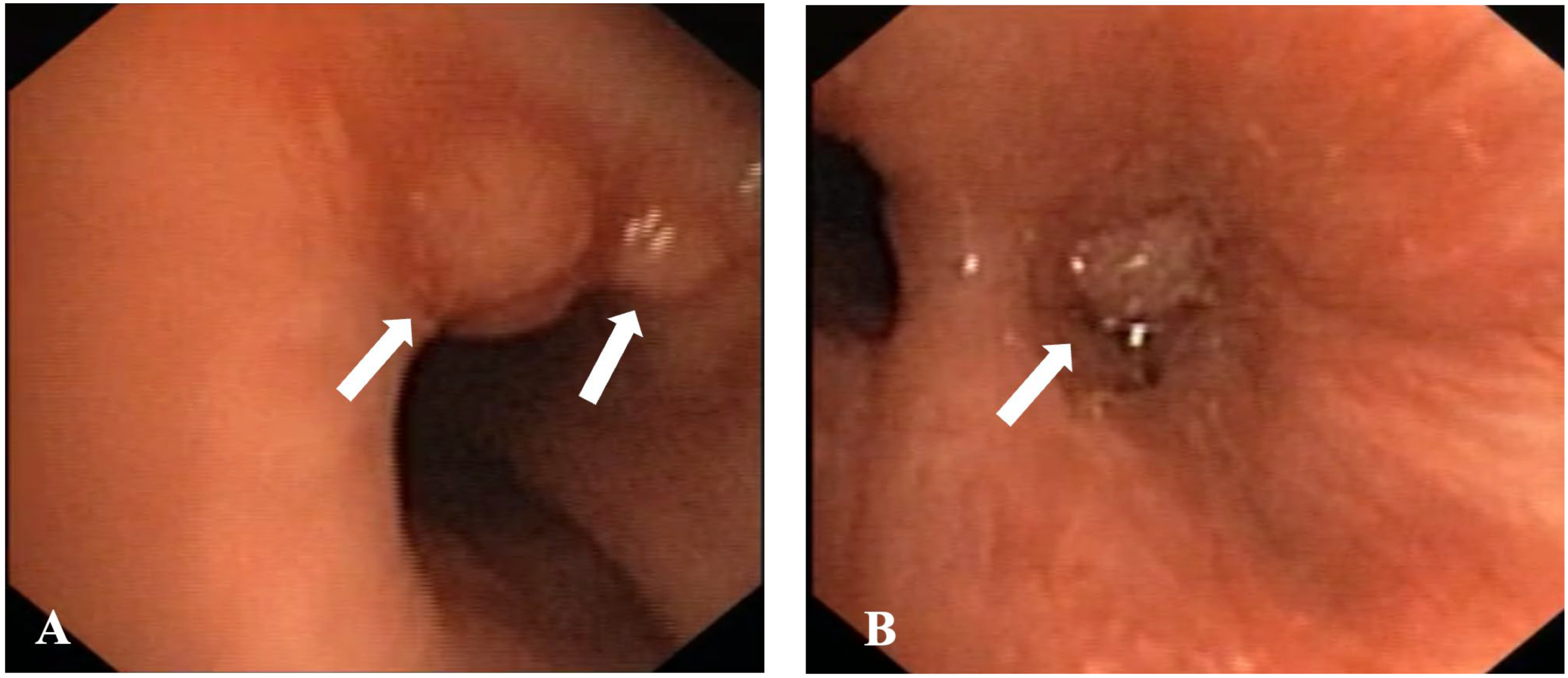

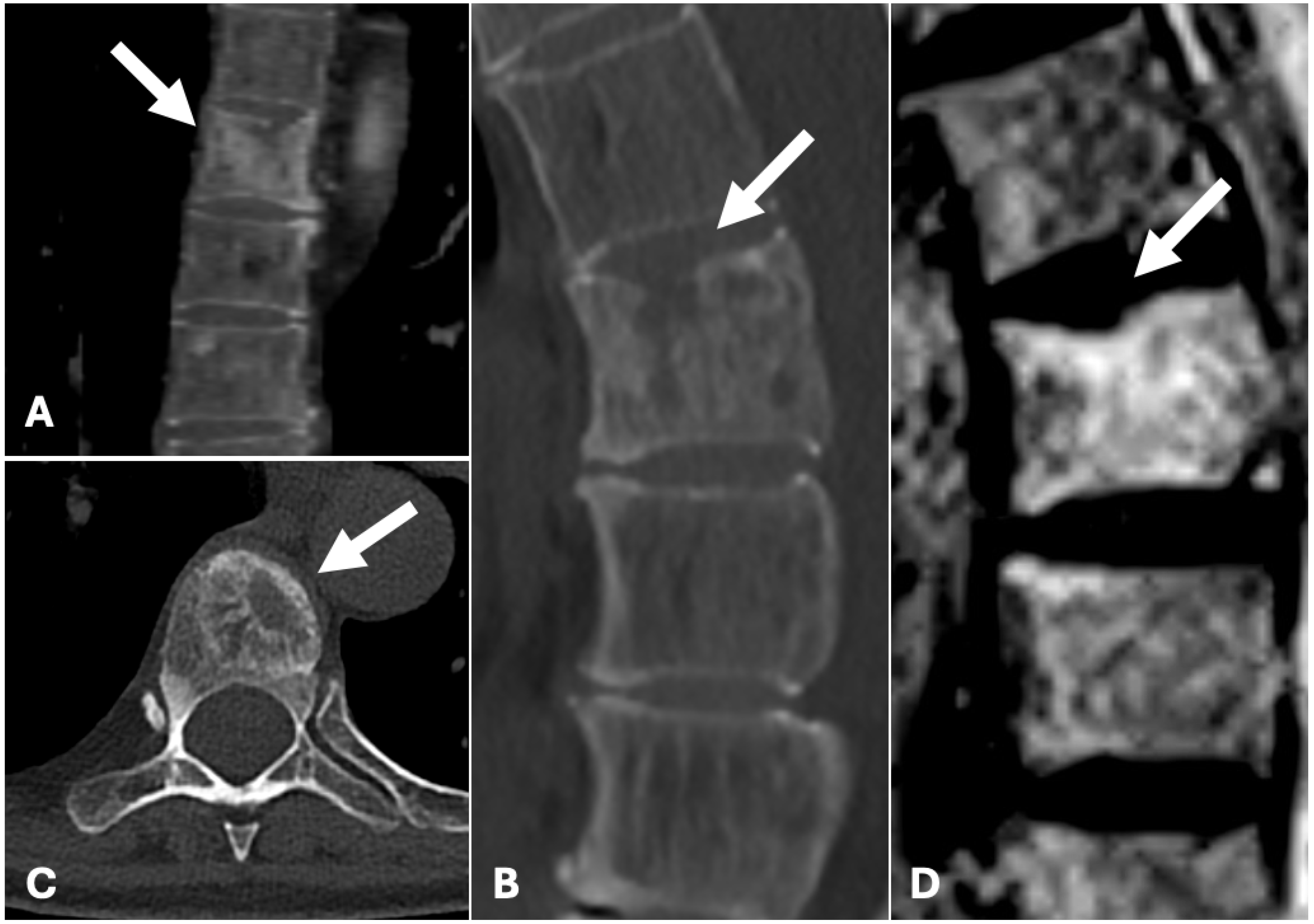

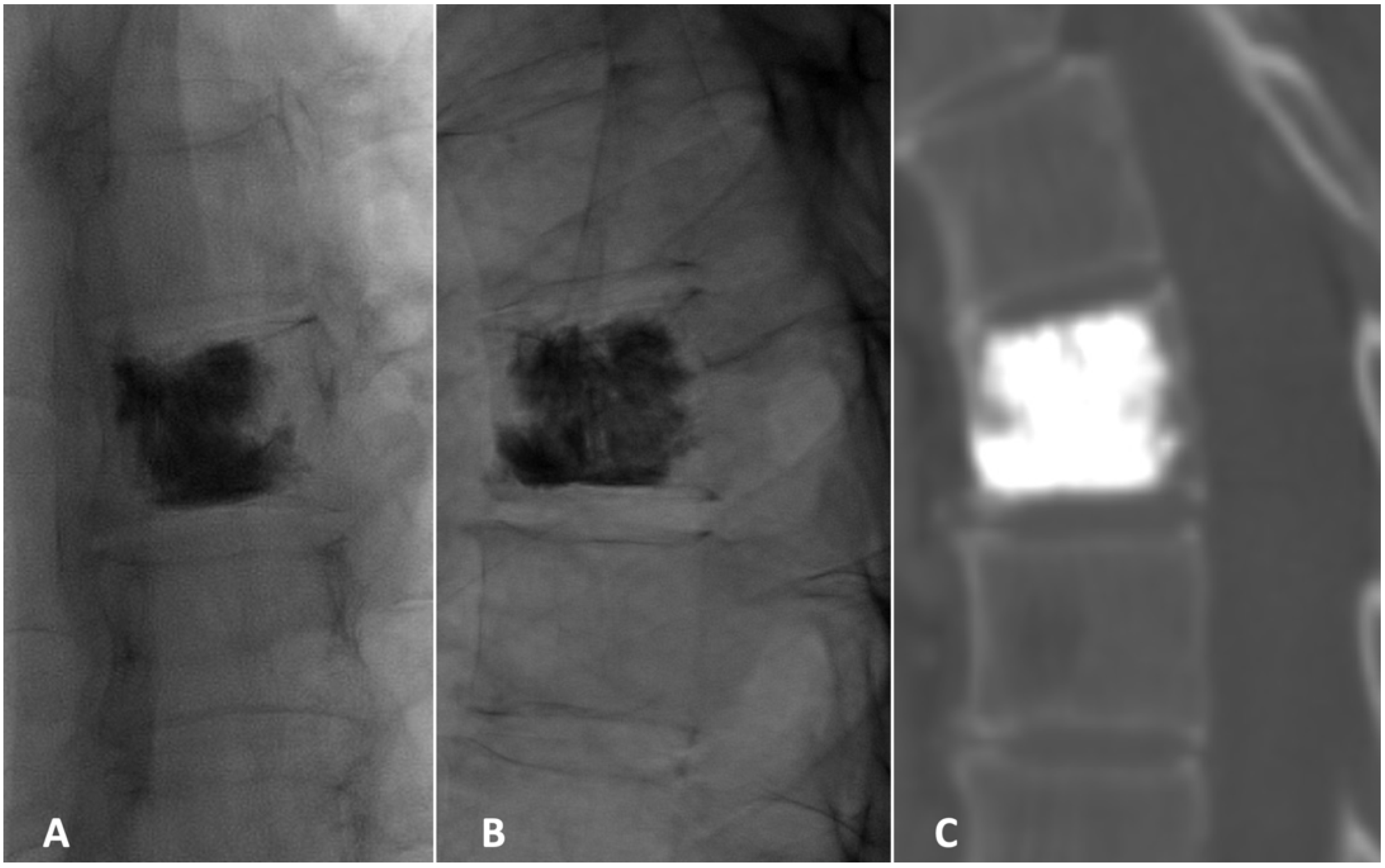

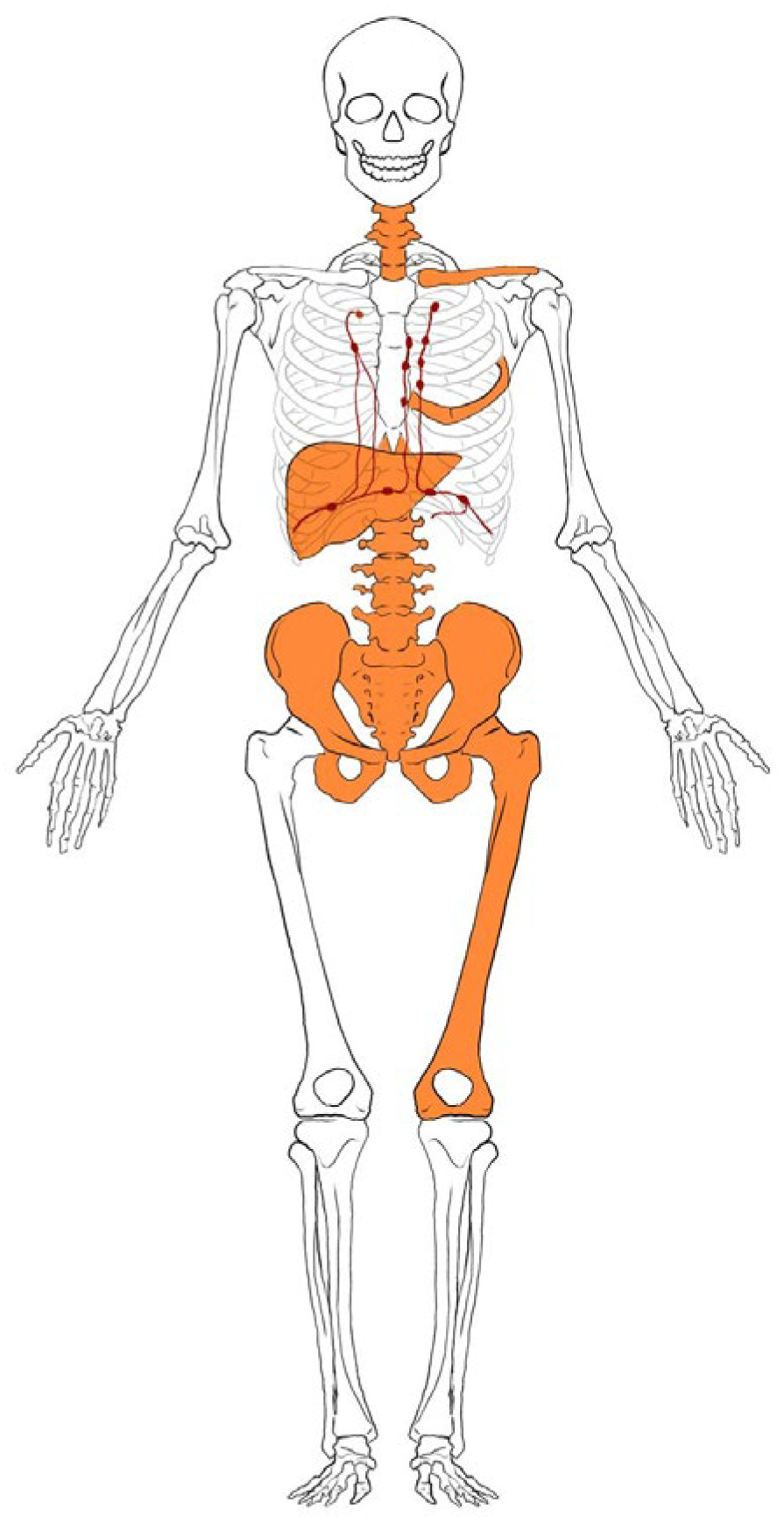

2. Case Presentation

3. Literature Review

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ito, T.; Kudoh, S.; Fujino, K.; Sanada, M.; Tenjin, Y.; Saito, H.; Nakaishi-Fukuchi, Y.; Kameyama, H.; Ichimura, T.; Udaka, N.; et al. Pulmonary Neuroendocrine Cells and Small Cell Lung Carcinoma: Immunohistochemical Study Focusing on Mechanisms of Neuroendocrine Differentiation. Acta Histochem. Cytochem. 2022, 55, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pelosi, G.; Sonzogni, A.; Harari, S.; Albini, A.; Bresaola, E.; Marchiò, C.; Massa, F.; Righi, L.; Gatti, G.; Papanikolaou, N.; et al. Classification of pulmonary neuroendocrine tumors: New insights. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2017, 6, 513–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Volante, M.; Mete, O.; Pelosi, G.; Roden, A.C.; Speel, E.J.M.; Uccella, S. Molecular Pathology of Well-Differentiated Pulmonary and Thymic Neuroendocrine Tumors: What Do Pathologists Need to Know? Endocr. Pathol. 2021, 32, 154–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ruggeri, R.M.; Altieri, B.; Razzore, P.; Retta, F.; Sperti, E.; Scotto, G.; Brizzi, M.P.; Zumstein, L.; Pia, A.; Lania, A.; et al. Gender-related differences in patients with carcinoid syndrome: New insights from an Italian multicenter cohort study. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2024, 47, 959–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pinchot, S.N.; Holen, K.; Sippel, R.S.; Chen, H. Carcinoid tumors. Oncologist 2008, 13, 1255–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- What Are Lung Carcinoid Tumors? Available online: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/lung-carcinoid-tumor/about/what-is-lung-carcinoid-tumor.html (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Kaifi, J.T.; Kayser, G.; Ruf, J.; Passlick, B. The Diagnosis and Treatment of Bronchopulmonary Carcinoid. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2015, 112, 479–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gade, A.K.; Olariu, E.; Douthit, N.T. Carcinoid Syndrome: A Review. Cureus 2020, 12, e7186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Granberg, D.; Juhlin, C.C.; Falhammar, H.; Hedayati, E. Lung Carcinoids: A Comprehensive Review for Clinicians. Cancers 2023, 15, 5440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Limaiem, F.; Tariq, M.A.; Ismail, U.; Wallen, J.M. Lung Carcinoid Tumors. [Updated 15 June 2023]. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537080/ (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Kiesewetter, B.; Mazal, P.; Kretschmer-Chott, E.; Mayerhoefer, M.E.; Raderer, M. Pulmonary neuroendocrine tumors and somatostatin receptor status: An assessment of unlicensed use of somatostatin analogues in the clinical practice. ESMO Open 2022, 7, 100478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dionigi, R. Chirurgia: Basi teoriche e chirurgia generale-Chirurgia specialistica. In Chirurgia: Basi Teoriche e Chirurgia Generale; Edra: Tuscany, Italy, 2022; Volume 2, EAN: 9788821454356; ISBN 8821454355. [Google Scholar]

- Watzka, F.M.; Fottner, C.; Miederer, M.; Schad, A.; Weber, M.M.; Otto, G.; Lang, H.; Musholt, T.J. Surgical therapy of neuroendocrine neoplasm with hepatic metastasis: Patient selection and prognosis. Langenbecks Arch. Surg. 2015, 400, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaedvlieg, P.F.; Visser, O.; Lamers, C.B.; Janssen-Heijen, M.L.; Taal, B.G. Epidemiology and survival in patients with carcinoid disease in The Netherlands. An epidemiological study with 2391 patients. Ann. Oncol. 2001, 12, 1295–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gagnier, J.J.; Kienle, G.; Altman, D.G.; Moher, D.; Sox, H.; Riley, D.; CARE Group. The CARE guidelines: Consensus-based clinical case report guideline development. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2014, 67, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riley, D.S.; Barber, M.S.; Kienle, G.S.; Aronson, J.K.; von Schoen-Angerer, T.; Tugwell, P.; Kiene, H.; Helfand, M.; Altman, D.G.; Sox, H.; et al. CARE guidelines for case reports: Explanation and elaboration document. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2017, 89, 218–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashraf, M.H. Bronchial carcinoid with osteoblastic metastases. Thorax 1977, 32, 509–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Angel, F.P.; Catalicio, J.S.; Salem, L.M.; Sánchez, M.C.; Fernández, J.N.; Valderas, M.C. Gammagrafía ósea y gammagrafía con (111)In-octreótido en el diagnóstico de metástasis óseas del tumor carcinoide bronquial [Bone scintigraphy and scintigraphy with (111)In-octreotide in the diagnosis of bone metastasis of bronchial carcinoid tumor]. Rev. Esp. Med. Nucl. 2010, 29, 38–39. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hori, T.; Yasuda, T.; Suzuki, K.; Kanamori, M.; Kimura, T. Skeletal metastasis of carcinoid tumors: Two case reports and review of the literature. Oncol. Lett. 2012, 3, 1105–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nguyen, B.D.; Ram, P.C. Bronchopulmonary Carcinoid Tumor and Related Cervical Vertebral Metastasis with PET-Positive and Octreotide-Negative Scintigraphy. Clin. Nucl. Med. 2006, 31, 101–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filosso, P.L.; Rena, O.; Donati, G.; Casadio, C.; Ruffini, E.; Papalia, E.; Oliaro, A.; Maggi, G. Bronchial carcinoid tumors: Surgical management and long-term outcome. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2002, 123, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Q.; Yang, W.; Zhang, Z.; Shao, Z. Rare Bone Metastasis of Neuroendocrine Tumors of Unknown Origin: A Case Report and Literature Review. Orthop. Surg. 2022, 14, 2766–2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Loon, K.; Zhang, L.; Keiser, J.; Carrasco, C.; Glass, K.; Ramirez, M.; Bobiak, S.; Nakakura, E.K.; Venook, A.P.; Shah, M.H.; et al. Bone metastases and skeletal-related events from neuroendocrine tumors. Endocr. Connect. 2015, 4, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkpatrick, D.B.; Dawson, E.; Haskell, C.M.; Batzdorf, U. Metastatic carcinoid presenting as a spinal tumor. Surg. Neurol. 1975, 4, 283–287. [Google Scholar]

- Orakwe, O. Bronchial carcinoid tumor: Case report. J. Lung Pulm. Respir. Res. 2014, 1, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuetenhorst, J.M.; Hoefnageli, C.A.; Boot, H.; Olmos, R.V.; Taal, B.G. Evaluation of 111In-pentetreotide, 131I-MIBG and bone scintigraphy in the detection and clinical management of bone metastases in carcinoid disease. Nucl. Med. Commun. 2002, 23, 735–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bora, M.K.; Vithiavathi, S. Primary bronchial carciniod: A rare differential diagnosis of pulmonary koch in young adult patient. Lung India 2012, 29, 59–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashimoto, K.; Nishimura, S.; Miyamoto, H.; Toriumi, K.; Ikeda, T.; Akagi, M. Comprehensive treatment outcomes of giant cell tumor of the spine: A retrospective study. Medicine 2022, 101, e29963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chen, J.; Sun, J.; Li, K. The Formation of NETs and Their Mechanism of Promoting Tumor Metastasis. J. Oncol. 2023, 2023, 7022337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kobashi, Y.; Shimizu, H.; Mouri, K.; Irei, T.; Oka, M. Clinical usefulness of fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose PET in a case with multiple bone metastases of carcinoid tumor after ten years. Intern. Med. 2009, 48, 1919–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Taal, B.G.; Hoefnagel, C.A.; Olmos, R.V.; Boot, H. Combined diagnostic imaging with 131I-metaiodobenzyl- guanidine and 111In- pentetreotide in carcinoid tumors. Eur. J. Cancer 1996, 32, 1924–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łukaszewski, B.; Nazar, J.; Goch, M.; Łukaszewska, M.; Stępiński, A.; Jurczyk, M.U. Diagnostic methods for detection of bone metastases. Contemp. Oncol. 2017, 21, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Baudin, E.; Caplin, M.; Garcia-Carbonero, R.; Fazio, N.; Ferolla, P.; Filosso, P.L.; Frilling, A.; de Herder, W.W.; Hörsch, D.; Knigge, U.; et al. Electronic address: Clinicalguidelines@esmo.org. Lung and thymic carcinoids: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2021, 32, 439–451, Erratum in Ann. Oncol. 2021, 32, 1453–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faduyile, F.A.; Sanni, D.A.; Soyemi, S.S.; Taiwo, O.J.; Benebo, A.S. Atypical carcinoid tumor of the lung: An enigma. World J. Pathol. 2012, 3, 9. [Google Scholar]

| n. pts | Sex | Ag | Metastasis Location | Symptoms Prior Surgery | Type of Intervention | Post-op Follow-Up | Symptoms After Surgery | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ashraf MH (1977) [21] | 1 | M | 48 | Left clavicle, multiple osteoblastic deposits in the right clavicle, vertebrae and sternum. | Pain at the right clavicle. | None. | - | - |

| Pérez Angel F (2009) [22] | 1 | M | 80 | Pelvic localisation. | - | - | - | - |

| Hori T (2012) [23] | 2 | M 1/2 | 59 *1 74 *2 | Thoracic spine localisation *1; osteolytic lesion in the shaft of the left femur *2. | Back pain and numbness in the lower limbs; none until lesion of the femur *2. | Spinal decompression *1; intramedullary nail and courettage *2. | 1 y *1; - | Slight numbness in his leg *1. - |

| Nguyen Ba D. (2006) [24] | 1 | M | 70 | C5. | Not reported. | Radiation therapy. | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Biz, C.; Rodà, M.G.; Mori, F.; Costa, L.; Gabrieli, J.D.; Causin, F.; Ruggieri, P. Vertebral Metastasis in a Bronchial Carcinoid: A Rare Case Report with More than 3-Year Follow-Up and Review of the Literature. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 1128. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15091128

Biz C, Rodà MG, Mori F, Costa L, Gabrieli JD, Causin F, Ruggieri P. Vertebral Metastasis in a Bronchial Carcinoid: A Rare Case Report with More than 3-Year Follow-Up and Review of the Literature. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(9):1128. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15091128

Chicago/Turabian StyleBiz, Carlo, Maria Grazia Rodà, Fabiana Mori, Lorenzo Costa, Joseph Domenico Gabrieli, Francesco Causin, and Pietro Ruggieri. 2025. "Vertebral Metastasis in a Bronchial Carcinoid: A Rare Case Report with More than 3-Year Follow-Up and Review of the Literature" Diagnostics 15, no. 9: 1128. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15091128

APA StyleBiz, C., Rodà, M. G., Mori, F., Costa, L., Gabrieli, J. D., Causin, F., & Ruggieri, P. (2025). Vertebral Metastasis in a Bronchial Carcinoid: A Rare Case Report with More than 3-Year Follow-Up and Review of the Literature. Diagnostics, 15(9), 1128. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15091128