Nurse-Administered Sedation in Digestive Endoscopy: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Sources of Information

2.2. Search Strategies

2.3. Study Selection

- Studies involving patients undergoing digestive endoscopies with sedation administered by nurses.

- Articles published in the last five years.

- Research that evaluates the efficacy, safety, patient satisfaction or training of nurses in sedation

- Studies conducted on animals or simulations not applied to people.

- Opinion articles, editorials or nonsystematic reviews.

- Investigations without specific data on administered sedation.

2.4. Quality Assessment

2.5. Data Extraction and Analysis

3. Results

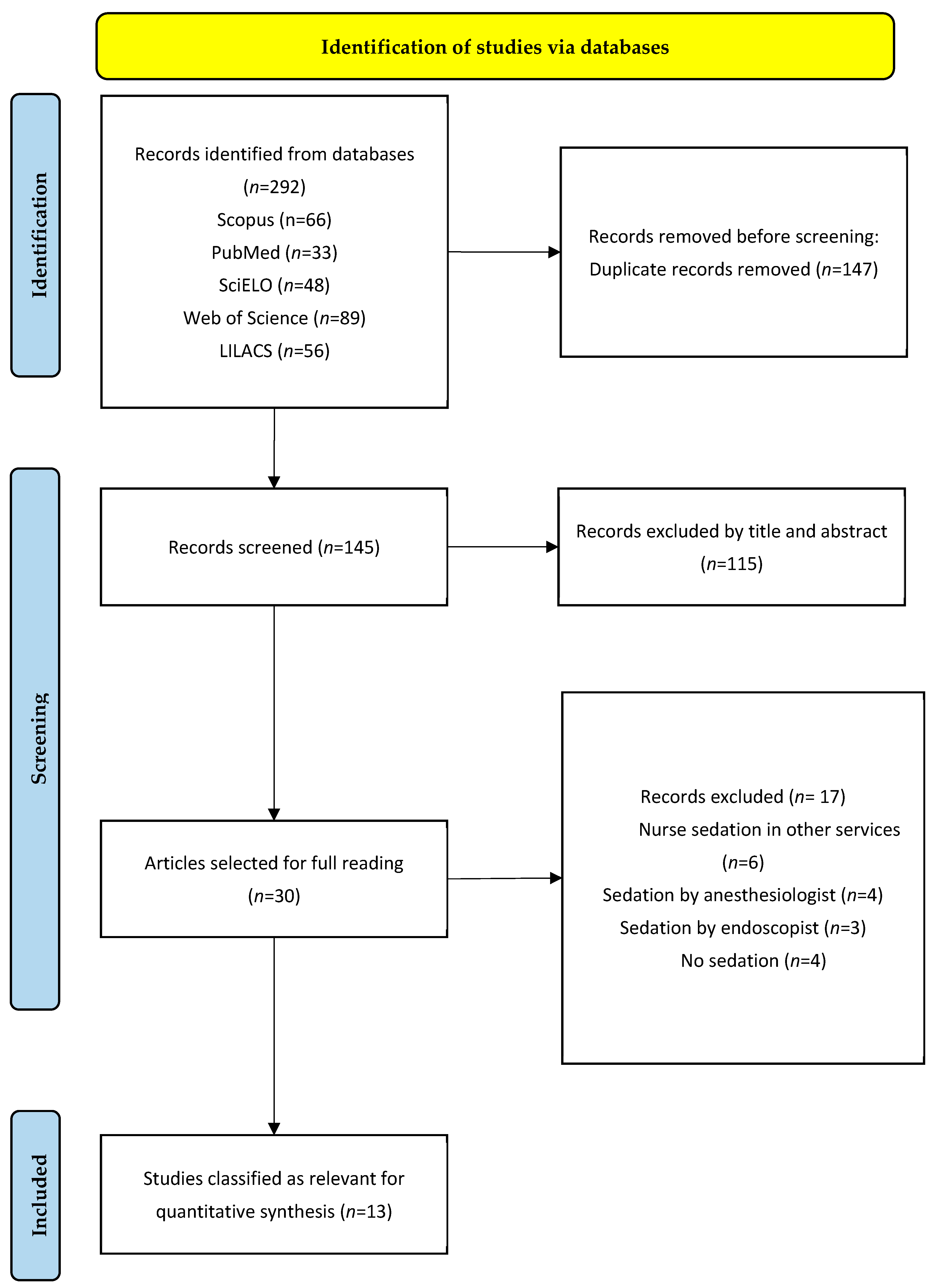

3.1. Selection of Studies

3.2. Characteristics of the Selected Studies

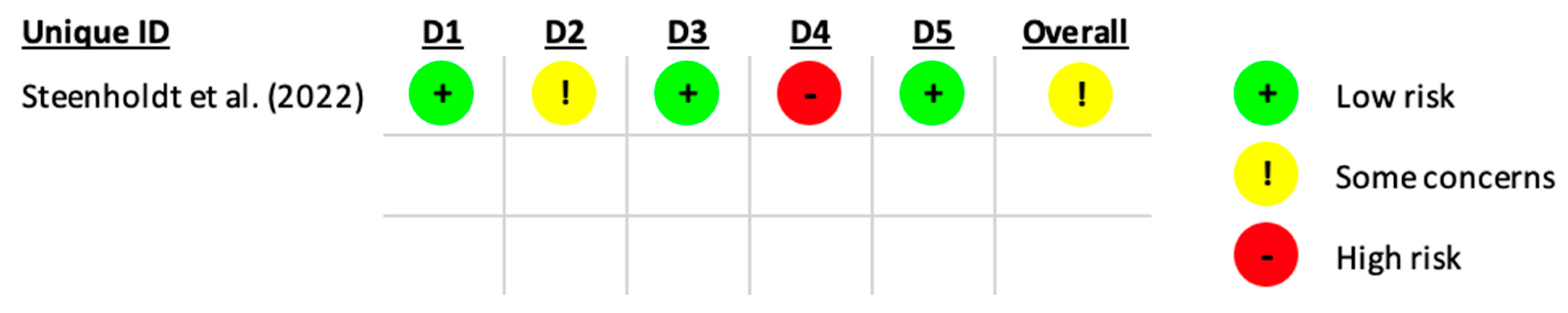

3.3. Assessment of Risk of Bias

3.4. Efficacy of Sedation Administered by Nurses in Digestive Endoscopies

3.5. Safety and Management of Complications During Sedation Administered by Nurses

3.6. Patient Satisfaction and Experience with Nurse-Administered Sedation

4. Discussion

Limitations and Strengths

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Skiljic, S.; Budrovac, D.; Cicvaric, A.; Neskovic, N.; Kvolik, S. Advances in Analgosedation and Periprocedural Care for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Life 2023, 13, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Deng, H.; Xiong, Z.; Gong, P.; Ye, M.; Liu, T.; Long, X.; Tian, L. A scale to measure the worry level in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy with sedation: Development, reliability, and validity. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2023, 23, 100410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsubayashi, M.; Nakamura, K.; Sugawara, M.; Kamishima, S. Nursing Difficulties and Issues in Endoscopic Sedation. Gastroenterol. Nurs. 2021, 45, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramírez-Quesada, W.; Rezvani-Monge, F.; Dávila-Martínez, D.; Vargas-Madrigal, J. Safety of propofol sedation administered by gastroenterologists in digestive endocopy. Acta Med. Costarric. 2019, 5, 60–67. [Google Scholar]

- Quesada, W.R.; Monge, F.R.; Martínez, D.D.; Madrigal, J.V. Seguridad de la sedación con propofol administrado por gastroenterólogos en endoscopia digestiva. Acta Med. Costarric. 2020, 61, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dossa, F.; Megetto, O.; Yakubu, M.; Zhang, D.D.Q.; Baxter, N.N. Sedation practices for routine gastrointestinal endoscopy: A systematic review of recommendations. BMC Gastroenterol. 2021, 21, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, D.K.; Gastmans, C.; Vandyk, A.; de Casterlé, B.D. Moral identity and palliative sedation: A systematic review of normative nursing literature. Nurs. Ethics 2020, 27, 868–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussakhkhar, A.; Romero Xandre, J.; Pérez Berbegal, R.; Parrilla Carrasco, M.; Font Lagarriga, X.; Casals Urquiza, G. Importance of the nurse’s role in the quality of digestive endoscopy: An approach to advanced practice nursing. Enferm. Endosc. Dig. 2023, 10, 4–15. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Q.; Wu, B.; Wu, W.; Wang, R. Adoption and Safety Evaluation of Comfortable Nursing by Mobile Internet of Things in Pediatric Outpatient Sedation. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2022, 2022, 3257101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galloro, G.; Pisani, A.; Zagari, R.M.; Lamazza, A.; Cengia, G.; Ciliberto, E.; Conigliaro, R.L.; Da Masa, P.; Germana, B.; Pasquale, L. Safety in digestive endoscopy procedures in the covid era recommendations in progres of the italian society of digestive endoscopy. Dig. Liver Dis. 2020, 52, 800–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sneyd, J.R. Developments in procedural sedation for adults. BJA Educ. 2022, 22, 258–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, S.L.; Rowles, J.S. (Eds.) Nurse Practitioners and Nurse Anesthetists: The Evolution of the Global Roles; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; p. 466. [Google Scholar]

- Cherciu Harbiyeli, I.F.; Burtea, D.E.; Serbanescu, M.S.; Nicolau, C.D.; Saftoiu, A. Implementation of a Customized Safety Checklist in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy and the Importance of Team Time Out-A Dual-Center Pilot Study. Medicina 2023, 59, 1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, L.L.; Zhang, M.M. Up-to-date literature review and issues of sedation during digestive endoscopy. Videosurg. Other Miniinvasive Tech. 2023, 18, 418–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKenzie, P.; Fang, J.; Davis, J.; Qiu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Adler, D.G.; Gawron, A.J. Safety of endoscopist-directed nurse-administered balanced propofol sedation in patients with severe systemic disease (ASA class III). Gastrointest. Endosc. 2021, 94, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias-Rivera, S.; López-López, C.; Frade-Mera, M.J.; Via-Clavero, G.; Rodríguez-Mondéjar, J.J.; Sánchez-Sánchez, M.M.; Acevedo-Nuevo, M.; Gil-Castillejos, D.; Robleda, G.; Cachón-Pérez, M.; et al. Assessment of analgesia, sedation, physical restraint and delirium in patients admitted to Spanish intensive care units. Proyecto ASCyD. Enferm. Intensiv. 2020, 31, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simón, M.A.; Bordas, J.M.; Campo, R.; González-Huix, F.; Igea, F.; Monés, J. Documento de consenso de la Asociación Española de Gastroenteología sobre sedoanalgesia en la endoscopia digestiva. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2006, 29, 131–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igea, F.; Casellas, J.A.; González-Huix, F.; Gómez-Oliva, C.; Baudet, J.S.; Cacho, G.; Simón, M.A.; de la Morena, E.; Lucendo, A.; Vida, F.; et al. Sedation for gastrointestinal endoscopy. Clinical practice guidelines of the Sociedad Española de Endoscopia Digestiva ARTÍCULO ESPECIAL. Rev. Esp. Enferm. Dig. 2014, 106, 195–211. [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo-Cabanillas, M.; Laredo-Aguilera, J.A.; López-Fernández-Roldán, Á.; Molina-Madueño, R.M.; Rodriguez-Muñoz, P.M.; Navarrete-Tejero, C.; López-González, Á.; Rabanales-Sotos, J.; Carmona-Torres, J.M. Training and Resources Related to the Administration of Sedation by Nurses During Digestive Endoscopy: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare 2024, 12, 2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín-Gabriel, J.C.; Santiago, E.R.d. AEG-SEED position paper for the resumption of endoscopic activity after the peak phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 43, 389–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surges, S.M.; Garralda, E.; Jaspers, B.; Brunsch, H.; Rijpstra, M.; Hasselaar, J.; Van der Elst, M.; Menten, J.; Csikós, Á.; Mercadante, S.; et al. Review of European Guidelines on Palliative Sedation: A Foundation for the Updating of the European Association for Palliative Care Framework. J. Palliat. Med. 2022, 25, 1721–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paneque, I.; Calvo-Calvo, M.Á.; Rubio-Guerrero, C.; Frutos-López, M.; Arana-Rueda, E.; Pedrote, A. Deep Sedation With Propofol Administered by Electrophysiologists in Atrial Fibrillation Ablation. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2018, 71, 683–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Cuadrado-Robles, E.; Pinho, R.; González, B.; De Ferro, S.M.; Chagas, C.; Delgado, P.E.; Carretero, C.; Figueiredo, P.; Rosa, B.; García-Lledó, J.; et al. Small bowel enteroscopy—A joint clinical guideline by the Spanish and Portuguese small-bowel study groups. Rev. Esp. Enferm. Dig. 2020, 112, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, S.; Zhu, Z.; Dai, W.; Qi, S.; Tian, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Huang, L.; Tian, J.; Yu, W.; et al. National survey on sedation for gastrointestinal endoscopy in 2758 Chinese hospitals. Br. J. Anaesth. 2021, 127, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagula, S.; Parasa, S.; Laine, L.; Shah, S.C. AGA Clinical Practice Update on High-Quality Upper Endoscopy: Expert Review. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 22, 933–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elmunzer, B.J.; Anderson, M.A.; Mishra, G.; Rex, D.K.; Yadlapati, R.; Shaheen, N.J. Quality indicators common to all GI endoscopic procedures. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2024, 100, 382–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hidalgo-Cabanillas, M.; Laredo-Aguilera, J.A.; Cobo-Cuenca, A.I.; Molina-Madueño, R.M.; Santacruz-Salas, E.; Rodriguez-Muñoz, P.M.; Carmona-Torres, J.M. Patient satisfaction and safety in the administration of sedation by nursing staff in the digestive endoscopy service: A cross-sectional study. BMC Nurs. 2024, 23, 953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werthman, J.A.; Maxwell, C.A.; Dietrich, M.S.; Jordan, L.M.; Minnick, A.F. Moderate Sedation Education for Nurses in Interventional Radiology to Promote Patient Safety: Results of a National Survey. J. Radiol. Nurs. 2021, 40, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepúlveda, M.; Rojas, N.E.; Herrera-Lara, E.; Sánchez-Londoño, S.; Pérez, J.S.; Castaño, J.P.; García-Navarrete, M.E.; Tobón, A.; García, J.; Jiménez, D.; et al. Sedation Administered by General Practitioners for Low Complexity Endoscopic Procedures: Experience in an Endoscopy Unit of a Tertiary Referral Hospital in Cali. Rev. Colomb. Gastroenterol. 2022, 37, 276–281. [Google Scholar]

- Kudaravalli, P.; Riaz, S.; Saleem, S.A.; Pendela, V.S.; Austin, P.N.; Farenga, D.A.; Lowe, D.; Arif, M.O. Patient Satisfaction and Understanding of Moderate Sedation During Endoscopy. Cureus 2020, 12, e7693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshijima, H.; Higuchi, H.; Sato (boku), A.; Shibuya, M.; Morimoto, Y.; Fujisawa, T.; Mizuta, K. Patient satisfaction with deep versus light/moderate sedation for nonsurgical procedures: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 2021, 100, E27176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minciullo, A.; Filomeno, L. Nurse-Administered Propofol Sedation Training Curricula and Propofol Administration in Digestive Endoscopy Procedures: A Scoping Review of the Literature. Gastroenterol. Nurs. 2024, 47, 33.40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conigliaro, R.; Pigò, F.; Gottin, M.; Grande, G.; Russo, S.; Cocca, S.; Marocchi, M.; Lupo, M.; Marsico, M.; Sculli, S.; et al. Safety of endoscopist-directed nurse-administered sedation in an Italian referral hospital: An audit of 2 years and 19,407 procedures. Dig. Liver Dis. 2025, 57, 630–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steenholdt, C.; Jensen, J.T.; Brynskov, J.; Møller, A.M.; Limschou, A.C.; Konge, L.; Vilman, P. Patient Satisfaction of Propofol Versus Midazolam and Fentanyl Sedation During Colonoscopy in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 20, 559–568.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez Del Río, A.; Campo, R.; Llach, J.; Pons, V.; Mreish, G.; Panadés, A.; Parra-Blanco, A. Satisfacción del paciente con la endoscopia digestiva: Resultados de un estudio multicéntrico. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2008, 31, 566–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- José, S.A. Encuesta de satisfacción tras la realización de una endoscopia digestiva. Satisfaction survey after performing a digestive endoscopy. Enferm. Endosc. Dig. 2017, 4, 14–20. [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Rojas, J.; Gutiérrez-Martínez, A.; Chávez-Tostado, M.; González-Ojeda, A.; Gómez-Reyes, E.; Vázquez-Elizondo, G. Level of satisfactian from patients who undergone an endoscopic procedure and related factors. Rev. Gastroenterol. Mex. 2021, 86, 263–269. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Sabater, A.; Chover-Sierra, P.; Chover-Sierra, E. Spanish Nurses’ Knowledge about Palliative Care. A National Online Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morato, R.; Tomé, L.; Dinis-Ribeiro, M.; Rolanda, C. Endoscopic Skills Training: The Impact of Virtual Exercises on Simulated Colonoscopy. GE Port. J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 29, 374–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aromataris, E.; Lockwood, C.; Porritt, K.; Pilla, B.; Jordan, Z. (Eds.) JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2024; Available online: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomized trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Green, S. (Eds.) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0; The Cochrane Collaboration: London, UK, 2011; Available online: www.handbook.cochrane.org (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Yamaguchi, D.; Nagatsuma, G.; Sakata, Y.; Mizuta, Y.; Nomura, T.; Jinnouchi, A.; Gondo, K.; Asahi, R.; Ishida, S.; Kimura, S.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of Sedation During Emergency Endoscopy for Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding: A Propensity Score Matching Analysis. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2023, 68, 1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.S.; Nagra, N.; La Selva, D.; Kozarek, R.A.; Ross, A.; Weigel, W.; Beecher, R.; Chiorean, M.; Gluck, M.; Boden, E.; et al. Nurse-Administered Propofol Continuous Infusion Sedation for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy in Patients Who Are Difficult to Sedate. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 19, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, M.; Horiuchi, A.; Tamaki, M.; Ichise, Y.; Kajiyama, M.; Yamamoto, Y.; Tanaka, N. Safety and Effectiveness of Nurse-Administered Propofol Sedation in Outpatients Undergoing Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 17, 1098–1104.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monsma-Muñoz, M.; Romero-García, E.; Montero-Sánchez, F.; Tevar-Yudego, J.; Silla-Aleixandre, I.; Pons-Beltrán, V.; Argende-Navarro, D. Retrospective observational study on safety of sedation for colonoscopies in ASA I and II patients performed by a nurse and under the supervision of anesthesiology. Rev. Esp. Anestesiol. Reanim. 2022, 69, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gururatsakul, M.; Lee, R.; Ponnuswamy, S.K.; Gilhotra, R.; McGowan, C.; Whittaker, D.; Ombiga, J.; Boyd, P. Prospective audit of the safety of endoscopist-directed nurse-administered propofol sedation in an Australian referral hospital. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 36, 490–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiankanon, K.; Mekaroonkamol, P.; Pittayanon, R.; Kongkam, P.; Gonlachanvit, S.; Rerknimitr, R. Nurse Administered Propofol Sedation (NAPS) versus On-call Anesthesiologist Administered Propofol Sedation (OAPS) in Elective Colonoscopy. J. Gastrointest. Liver Dis. 2020, 29, 579–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, O.S.; La Selva, D.; Kozarek, R.A.; Weigel, W.; Beecher, R.; Gluck, M.; Boden, E.; Venu, N.; Krishnamohorti, R.; Larsen, M.; et al. Nurse-Administered Propofol Continuous Infusion Sedation: A New Paradigm for Gastrointestinal Procedural Sedation. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 116, 710–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manno, M.; Deiana, S.; Gabbani, T.; Gazzi, M.; Pignatti, A.; Becchi, E.; Ottaviani, L.; Vavassori, S.; Sacchi, E.; Hassan, C.; et al. Implementation of the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) and European Society of Gastroenterology and Endoscopy Nurses and Associates (ESGENA) sedation training course in a regular endoscopy unit. Endoscopy 2021, 53, 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Moola, S.; Munn, Z.; Tufanaru, C.; Aromataris, E.; Sears, K.; Sfetcu, R.; Currie, M.; Lisy, K.; Qureshi, R.; Mattis, P.; et al. Chapter 7: Systematic reviews of etiology and risk. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.C.; Ganion, N.; Knebel, P.; Bopp, C.; Brenner, T.; Weigand, M.A.; Sauer, P.; Schaible, A. Sedation-related complications during anesthesiologist-administered sedation for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: A prospective study. BMC Anesthesiol. 2020, 20, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; MClinSc, S.M.; Lisy, K.; Riitano, D.; Tufanaru, C. Methodological guidance for systematic reviews of observational epidemiological studies reporting prevalence and cumulative incidence data. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inzunza Sosa, J.; Sandoval Rivera, A.G.; Arce Bojórquez, B.; Urias Romo del Vivar, E.G.; Chacón Uraga, E.J. Prevalence of anesthetic complications in surgical procedures outside the operating room. Acta Médica Grupo Ángeles 2017, 15, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciriza De Los Ríos, C.; Fernández Eroles, A.L.; García Menéndez, L.; Carneros Martín, J.A.; Díez Hernández, A.; Delgado Gómez, M. Sedation in upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Analysis of tolerance, complications and cost-effectiveness. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2004, 28, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez, O.; Ballesteros, D.; Estébanez, B.; Chana, M.; López, B.; Martín, C.; Algaba, Á.; Vigilia, L.; Blancas, R. Characteristics of deep sedaation in gastrointestinal endoscopic procedures performed by intensivists. Med. Intensiv. 2014, 38, 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieczorek-Wójcik, B.; Gaworska-Krzemińska, A.; Szynkiewicz, P.; Wójcik, M.; Orzechowska, M.; Kilańska, D. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of Improving Nurses’ Education Level in the Context of In-Hospital Mortality. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerrero-Menéndez, R.; Fontán-Vinagre, G.; Cobos-Serrano, J.L.; Ayuso-Murillo, D. The advancement of critical care nursing as a response to the current demands. Enferm. Intensiv. 2024, 35, e23–e29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidhu, R.; Turnbull, D.; Haboubi, H.; Leeds, J.S.; Healey, C.; Hebbar, S.; Collins, P.; Jones, W.; Peerally, M.F.; Brogden, S.; et al. British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines on sedation in gastrointestinal endoscopy. Gut 2024, 73, 219–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, J.; Cabadas, R.; de la-Matta, M. Patient safety under deep sedation for digestive endoscopic procedures. Rev. Esp. Enferm. Dig. 2017, 109, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Andrade, T.R.; Salluh, J.I.F.; Garcia, R.; Farah, D.; da Silva, P.S.L.; Bastos, D.F.; Fonseca, M.C. A cost-effectiveness analysis of propofol versus midazolam for the sedation of adult patients admitted to the intensive care unit. Rev. Bras. Ter. Intensiv. 2021, 33, 428–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Population | Intervention | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Patients undergoing digestive endoscopies | Nurse-administered sedation | Efficacy, safety and patient satisfaction in nurse-administered sedation |

| Database | Keywords | Search String |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed | Sedation, endoscopy, nurses | (Sedation AND endoscopy AND nurses) OR (Complications AND sedation AND endoscopy) |

| Scopus | Safety, complications, management | (“Sedation administered by nurses” AND “complications” OR “management”) |

| SciELO | Training, cost-effectiveness, satisfaction | ((Nurse-administered sedation) AND (patient satisfaction OR safety)) AND NOT pediatrics |

| Web of Science | Evaluation, rates, protocols | (Nurse AND sedation AND “endoscopic procedures” NOT “pediatric cases”) |

| LILACS | Nurses, endoscopy, quality | (MeSH terms: “Nurse-administered sedation” AND “Endoscopy”) |

| Author/ Year | Design | Participants | Nurses Received ALS Training | Country | Results | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conigliaro et al. (2024) [33] | Retrospective observational | N = 14,415 | Yes | Italy | The results showed low rates of adverse events (6% hypotension, 0.9% bradycardia) and a minimal percentage (0.01%) of serious complications that required intubation. | Nurse-administered sedation directed by endoscopists is safe and effective in low-risk patients, standing out as a viable option in routine endoscopies. |

| Lee et al. (2021) [45] | Retrospective observational | N = 1427 | Not specified | USA | The results indicated that patients with difficulties being sedated required higher doses of fentanyl and propofol, but the success rates of the procedures were high (95.1–100%), with similar procedure and recovery times compared to the control group. Adverse events were rare (26 cases), and no serious complications or deaths were recorded. | NAPCIS proved to be a safe and effective alternative to provide sedation in patients considered difficult to sedate. |

| Yamaguchi et al. (2023) [44] | Observational Retrospective divided into two groups with and without sedation | N = 171 | Not specified | Japan | The results show that the sedation group had a significantly shorter procedure time (17.6 vs. 20.2 min, p = 0.04), with similar success rates in both groups. The complication rate was hypotension 3%, bradycardia 2.3% and hypoxia 1.5%. No significant differences were found in the incidence of adverse events or mortality. | The sedation administered during emergency endoscopies by HDA is safe; in addition, it reduces the time of the procedure and does not increase the risk of complications. |

| Sato et al. (2019) [46] | Observational Retrospective | N = 150.211 | Not specified | Japan | It was observed that the mean dose of propofol used was 77 mg for EGD and 99 mg for colonoscopy. As an adverse event, only 1.3% of patients required supplemental oxygen temporarily (1.4% for EGD and 0.8% in colonoscopy), with no cases of mechanical ventilation, severe hypotension or mortality. | Nurse-administered mono-sedation with propofol, using doses of less than 200 mg, has been shown to be a safe and effective approach for outpatient gastrointestinal endoscopies. |

| Monsma-Muñoz et al. (2022) [47] | Retrospective observational | N = 381 | Not specified | Spain | A total of 5% of the patients experienced oxygen desaturation (<90%), without requiring mask ventilation, while 7.35% presented hypotension and 3.94% bradycardia. In 22% of the cases, consultation with the supervising anesthesiologist was necessary. Patient satisfaction, evaluated on a scale of 1 to 5, reached an average of 4.27, and perceived pain was minimal according to a numerical verbal scale. | Nurse-administered sedation following a consensual protocol proved to be safe and effective in low-risk patients, reinforcing the viability of this care model. |

| Steenholdt et al. (2022) [34] | ECA | N = 130 | Not specified | Denmark | Patients with deep sedation had a significantly higher mean score (60.1 vs. 51.2; p < 0.001) due to less pain, more amnesia, greater pleasure with sedation and a positive experience compared to previous sedations. In addition, this group showed a greater willingness to undergo future colonoscopies with the same protocol. In terms of safety, no patient with NAPS presented desaturation <92%, in contrast to six cases in the moderate sedation group. | Deep sedation with propofol significantly improves patient satisfaction and may increase adherence to endoscopic monitoring programs in patients with IBD. |

| Hidalgo-Cabanillas et al. (2024) [19] | Prospective observational | N = 75 | Yes 64.2% | Spain | The results showed that 100% of the nurses were currently using sedation, but only a minority had received specialized training in sedation or advanced life support. In addition, significant differences were found in the availability of resources between hospitals. | The training of nurses who perform sedation is insufficient, and the variability in resources and standards between hospitals suggests the need to implement continuous training programs, regulated at the institutional level, to improve the safety and effectiveness of the procedures. |

| Manno et al. (2021) [51] | Prospective observational | N = 10,755 | Yes | Italy | All staff (doctors and nurses) completed the ESGE-ESGENA sedation course. In total, 12,132 patients underwent endoscopic procedures, 10,755 (88.6%) of which were performed in a nonanesthesiological setting. Of these, approximately 20% used moderate sedation with midazolam + fentanyl, and 80% used deep sedation with additional propofol. There were no sentinel adverse events, 5 (0.05%) of moderate risk and 18 (0.17%) of lower risk, all during moderate or deep sedation, and all managed by endoscopy personnel without the need for assistance from the anesthesiologist. | After completing the ESGE-ESGENA sedation training program, the rate of adverse events was very low. The findings support the implementation of the program in all digestive endoscopy units and its inclusion in the curriculum for physicians and nurses to ensure safe endoscopic procedures. |

| Hidalgo-Cabanillas et al. (2024) [27] | Prospective observational | N = 660 | Not specified | Spain | Most of the patients indicated great satisfaction, especially valuing the care provided by the nurses. However, they negatively highlighted the waiting time for the appointment and the wait on the same day. The incidence of complications was minimal, with only 2% of cases, most of them transient desaturations. | The sedation administered by nurses in digestive endoscopy is effective and safe; this is because it shows high satisfaction and low complication. |

| McKenzie et al. (2021) [15] | Observational Retrospective | N = 18,910 | Yes | USA | The final sample size was 18,910 colonoscopy procedures and EGD procedures. In both colonoscopy and EGD procedures, there were no major adverse events. Mild adverse event rates were low (hypoxia 2.2%, hypotension 2.6% (32p) and bradycardia 4.4%) in both types of procedure and were not different between patients with ASA I/II and ASA III. | The EDNAPS is safe in both ASA I/II patients and ASA class III patients undergoing routine outpatient endoscopy. |

| Gururatsakul et al. (2021) [48] | Observational Retrospective | N = 24,958 | Yes | Australia | During the 78-month period, a total of 24,958 procedures were analyzed with EDNAPS. Of these, 9539 were ASA 1 (38.2%), 13,680 were ASA 2 (54.8%), 1733 were ASA 3 (6.9%) and 4 were ASA 4 (0.02%). Complications related to sedation occurred in 66 patients (0.26%), predominantly transient hypoxic episodes. No patient required intubation of the airway, and there was no mortality related to sedation. Complications related to sedation increased with the ASA class and were significantly more frequent with gastroscopy. | Propofol sedation administered by endoscopic nurses is a safe way to perform endoscopic sedation in low-risk patients in the hospital setting. |

| Tiankanon et al. (2020) [49] | Retrospective cohort | N = 189 | Yes | Thailand | A total of 278 eligible patients were included. There were 189 patients in the NAPS group and 63 in the OAPS group for analysis. Demographics were not different between the two groups. All procedures were technically successful with no difference in cecal intubation time. The dose of propofol/ kg/hour was significantly lower in the NAPS group (11.4 ± 4 mg/kg/hour versus 16.6 ± 8 mg/kg/hour; p < 0.001). There were fewer minor cardiopulmonary adverse events in NAPS compared to the OAPS group (2.2% vs. 4.7%; p = 0.014). | NAPS in elective colonoscopy in low-risk patients is as effective as OAPS but requires a significantly lower dose of propofol. Minor cardiopulmonary adverse events were recorded in the NAPS group compared to OAPS. |

| Lin et al. (2021) [50] | Cases and controls | N = 3331 | Yes | USA | The success rates of the NAPCIS procedures were high (99.1–99.2%) and similar to those observed in the CAPS (98.8–99.0%) and MF (99.0–99.3%) controls. The recovery times of NAPCIS were shorter than those of CAPS and MF. Validated physician and patient satisfaction scores were generally higher for NAPCIS subjects compared to CAPS and MF subjects. For NAPCIS, there were only four cases of oxygen desaturation and no serious complications related to sedation. These low complication rates were similar to those observed with CAPS (eight cases) and MF (three cases). | NAPCIS appears to be a safe, effective and efficient means of providing moderate sedation for upper endoscopy and colonoscopy in low-risk patients. |

| Conigliaro et al. (2024) [33] | Lee et al. (2021) [45] | Yamaguchi et al. (2023) [44] | Sato et al. (2019) [46] | Monsma-Muñoz et al. (2022) [47] | Hidalgo-Cabanillas et al. (2024) [19] | Manno et al. (2021) [51] | Hidalgo Cabanillas et al. (2024) [27] | McKenzie et al. (2021) [15] | Gururatsakul et al. (2021) [48] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Was the sample frame appropriate to address the target population? | |||||||||||

| Were study participants sampled in an appropriate way? | |||||||||||

| Was the sample size adequate? | |||||||||||

| Were the study subjects and the setting described in detail? | |||||||||||

| Was the data analysis conducted with sufficient coverage of the identified sample? | |||||||||||

| Were valid methods used for the identification of the condition? | |||||||||||

| Was the condition measured in a standard, reliable way for all participants? | |||||||||||

| Was there appropriate statistical analysis? | |||||||||||

| Was the response rate adequate, and if not, was the low response rate managed appropriately? | |||||||||||

| Yes | |||||||||||

| No | |||||||||||

| Unclear | |||||||||||

| Not applicable | |||||||||||

| Lin et al. (2021) [50] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Are the groups comparable other than the presence of disease in cases or the absence of disease in controls? | ||

| Are cases and controls matched appropriately? | ||

| Are the same criteria used for identification of cases and controls? | ||

| Was exposure measured in a standard, valid and reliable way? | ||

| Was exposure measured in the same way for cases and controls? | ||

| Were confounding factors identified? | ||

| Were strategies to deal with confounding factors stated? | ||

| Were outcomes assessed in a standard, valid and reliable way for cases and controls? | ||

| Was the exposure period of interest long enough to be meaningful? | ||

| Was appropriate statistical analysis used? | ||

| Yes | ||

| No | ||

| Unclear | ||

| Not applicable | ||

| Tiankanon et al. (2020) [49] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Was the sample frame appropriate to address the target population? | ||

| Were study participants sampled in an appropriate way? | ||

| Was the sample size adequate? | ||

| Were the study subjects and the setting described in detail? | ||

| Was the data analysis conducted with sufficient coverage of the identified sample? | ||

| Were valid methods used for the identification of the condition? | ||

| Was the condition measured in a standard, reliable way for all participants? | ||

| Was there appropriate statistical analysis? | ||

| Was the response rate adequate, and if not, was the low response rate managed appropriately? | ||

| Yes | ||

| No | ||

| Unclear | ||

| Not applicable | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hidalgo-Cabanillas, M.; Laredo-Aguilera, J.A.; Barroso-Corroto, E.; López-González, Á.; Rabanales-Sotos, J.; Carmona-Torres, J.M. Nurse-Administered Sedation in Digestive Endoscopy: A Systematic Review. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 1030. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15081030

Hidalgo-Cabanillas M, Laredo-Aguilera JA, Barroso-Corroto E, López-González Á, Rabanales-Sotos J, Carmona-Torres JM. Nurse-Administered Sedation in Digestive Endoscopy: A Systematic Review. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(8):1030. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15081030

Chicago/Turabian StyleHidalgo-Cabanillas, Miriam, José Alberto Laredo-Aguilera, Esperanza Barroso-Corroto, Ángel López-González, Joseba Rabanales-Sotos, and Juan Manuel Carmona-Torres. 2025. "Nurse-Administered Sedation in Digestive Endoscopy: A Systematic Review" Diagnostics 15, no. 8: 1030. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15081030

APA StyleHidalgo-Cabanillas, M., Laredo-Aguilera, J. A., Barroso-Corroto, E., López-González, Á., Rabanales-Sotos, J., & Carmona-Torres, J. M. (2025). Nurse-Administered Sedation in Digestive Endoscopy: A Systematic Review. Diagnostics, 15(8), 1030. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15081030