Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Presenting a Maxillary Mucosal Lesion as a First Visible Sign of Disease: A Case Report and Review of Literature

Abstract

1. Introduction

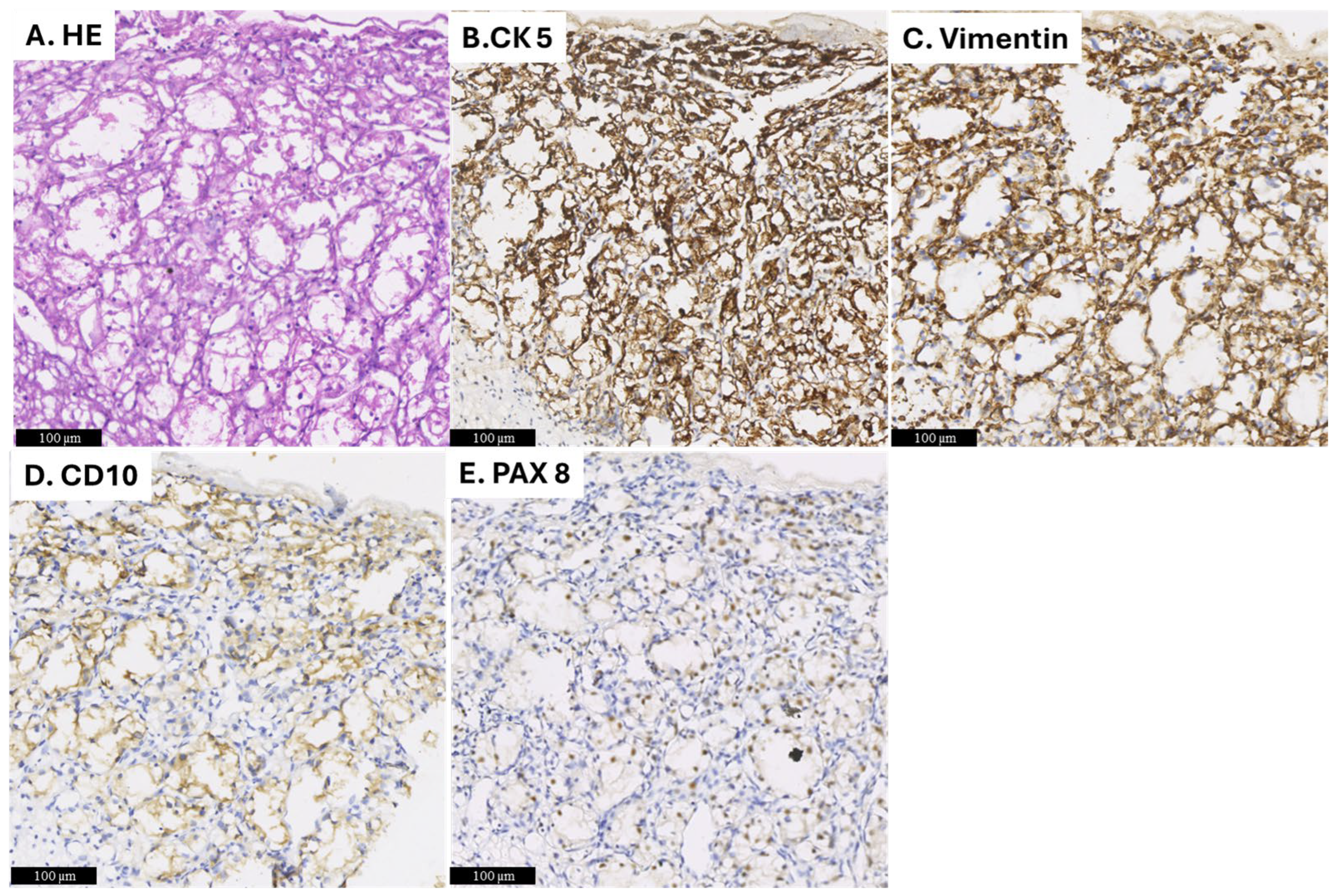

2. Detailed Case Description

3. Discussion

3.1. Overview of Renal Cell Carcinoma Metastasis

3.2. Diagnostic Challenges and Clinical Evaluation

3.3. Pathological Differential Diagnosis and Imaging Techniques

3.4. Treatment Options and Prognosis

3.5. Review of Literature

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- van der Waal, R.I.; Buter, J.; van der Waal, I. Oral metastases: Report of 24 cases. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2003, 41, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Will, T.A.; Agarwal, N.; Petruzzelli, G.J. Oral cavity metastasis of renal cell carcinoma: A case report. J. Med. Case Rep. 2008, 29, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maestre-Rodriguez, O.; Gonzalez-Garcia, R.; Mateo-Arias, J.; Moreno-García, C.; Serrano-Gil, H.; Villanueva-Alcojol, L.; Campos-de Orellana, A.N.; Monje-Gil, F. Case report: Metastasis of renal clear-cell carcinoma to the oral mucosa, an atypical location. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2009, 14, e601–e604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ganini, C.; Lasagna, A.; Ferraris, E.; Gatti, P.; Paglino, C.; Imarisio, I.; Morbini, P.; Benazzo, M.; Porta, C. Lingual metastasis from renal cell carcinoma: A case report and literature review. Rare Tumors 2012, 4, 130–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchyk, K.M.; Schiff, B.A.; Newkirk, K.A.; Krowiak, E.; Deeb, Z.E. Metastatic renal cell carcinoma to the head and neck. Laryngoscope 2002, 112, 1598–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morita, Y.; Iwagami, T.; Kawakita, C.; Kusuyama, Y.; Niki-Yonekawa, A.; Morita, N. Oral metastasis of renal cell carcinoma mimicking recurrence of excised malignant myoepithelioma: A case report. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 9, 66–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Vargo, R.J.; Bilodeau, E.A. Analytic survey of 57 cases of oral metastases. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2018, 47, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirshberg, A.; Shnaiderman-Shapiro, A.; Kaplan, I.; Berger, R. Metastatic tumors to the oral cavity—Pathogenesis and analysis of 673 cases. Oral Oncol. 2008, 44, 743–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Carranza, E.; Garcia-Perla, A.; Infante-Cossio, P.; Belmonte-Caro, R.; Loizaga-Iriondo, J.M.; Gutierrez-Perez, J.L. Airway obstruction due to metastatic renal cell carcinoma to the tongue. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 2006, 101, E76–E78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, R.A.E.; Mohamed, K.E.H. Metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma presenting with a gingival metastasis. Clin. Pract. 2016, 6, 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Suojanen, J.; Färkkilä, E.; Helkamaa, T.; Loimu, V.; Törnwall, J.; Lindqvist, C.; Hagström, J.; Mesimäki, K. Rapidly growing and ulcerating metastatic renal cell carcinoma of the lower lip: A case report and review of the literature. Oncol. Lett. 2014, 8, 2175–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwab, B.; Lee, W.T. Bilateral renal cell carcinoma metastasis in the oral cavity. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2012, 33, 154–155. [Google Scholar]

- Matamala, G.N.; Ángeles, M.D.L.; Toro, F. Oral metastasis of renal cell carcinoma, presentation of a case. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2008, 13, E742–E744. [Google Scholar]

- Altuntaş, O.; Petekkaya, İ.; Süslü, N.; Güllü, İ. Renal cell carcinoma metastatic to the tongue: A case report and literature review. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2015, 73, 1227–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilyeva, D.; Peters, S.M.; Philipone, E.M.; Yoon, A.J. Renal cell carcinoma metastatic to the maxillary gingiva: A case report and literature review. J. Oral Maxillofac. Pathol. 2018, 22, 102–107. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver-Puigdomènech, C.; González-Navarro, B.; Polis-Yanes, C.; Estrugo-Devesa, A.; Jané-Salas, E.; López-López, J. Incidence rate of metastases in the oral cavity: A review of all metastatic lesions in the oral cavity. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2021, 26, e619–e625. [Google Scholar]

- Boles, R.; Cerny, J. Head and neck metastases from renal carcinomas. Mich. Med. 1971, 90, 616–618. [Google Scholar]

- Granberg, V.; Laforgia, A.; Forte, M.; Di Venere, D.; Favia, G.; Copelli, C.; Manfuso, A.; Ingravallo, G.; d’Amati, A.; Capodiferro, S. Metastatic Renal-Cell Carcinoma of the Oro-Facial Tissues: A Comprehensive Review of the Literature with a Focus on Clinico–Pathological Findings. Surgeries 2024, 5, 694–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, I.; Raiser, V.; Shuster, A.; Shlomi, B.; Rosenfeld, E.; Greenberg, A.; Hirshberg, A.; Yahalom, R.; Shnaiderman-Shapiro, A.; Vered, M. Metastatic tumors in oral mucosa and jawbones: Unusual primary origins and unusual oral locations. Acta Histochem. 2019, 121, 151448. [Google Scholar]

- Eda, S.; Saito, T.; Yamamura, T.; Kawahara, H.; Takahashi, S. Two cases of renal-cell carcinoma metastatic to the gingiva. J. Tokyo Dent. Coll. Soc. 1973, 73, 1667–1674. [Google Scholar]

- Mori, M.; Sakamoto, M.; Amano, Y.; Kimura, J. Renal carcinoma with metastasis to gingiva: A review of the literature with report of a case. Jpn. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1974, 20, 614–620. [Google Scholar]

- Derakhshan, S.; Rahrotaban, S.; Mahdavi, N.; Mirjalili, F. Metastatic renal cell carcinoma presenting as maxillary lesion: Report of two rare cases. J. Oral Maxillofac. Pathol. 2018, 22 (Suppl. S1), S39–S43. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nifosìa, G.; Bressand, H.; Fabrizio, A.; Nifosì, L.; Nifosì, P.D. Epulis-like presentation of gingival renal cancer. Case Rep. Oncol. 2017, 10, 758–763. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshitomi, I.; Kawasaki, G.; Mizuno, A.; Nishikido, M.; Hayashi, T.; Fujita, S.; Ikeda, T. Lingual metastasis as an initial presentation of renal cell carcinoma. Med. Oncol. 2011, 28, 1389–1394. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, F.; Dai, L.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, L.; Niu, Y.; Jiang, N. Correction: Evaluating prognosis by CK7 differentiating renal cell carcinomas from oncocytomas can be used as a promising tool for optimizing diagnosis strategies. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 29285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiorano, E.; Altini, M.; Favia, G. Clear cell tumors of the salivary glands, jaws, and oral mucosa. Semin. Diagn. Pathol. 1997, 14, 203–212. [Google Scholar]

- Bellin, M.F.; Valente, C.; Bekdache, O.; Maxwell, F.; Balasa, C.; Savignac, A.; Meyrignac, O. Update on renal cell carcinoma diagnosis with novel imaging approaches. Cancers 2024, 16, 1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bark, R.; Mercke, C.; Munck-Wikland, E.; Wisniewski, N.A.; Hammarstedt-Nordenvall, L. Cancer of the gingiva. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2016, 273, 1335–1345. [Google Scholar]

- Kaddissi, A.E.; Ducleon, G.G.; Lefort, F.; Mezepo, G.; Frontczak, A.; Goujon, M.; Mouillet, G.; Almotlak, H.; Gross-Goupil, M.; Thiery-Vuillemin, A. Metastatic renal cell cancer and first-line combinations: For which patients? (focus on tolerance and health-related quality of life). Bull. Cancer 2022, 109 (Suppl. S2), 2S19–2S30. [Google Scholar]

- Kase, A.M.; George, D.J.; Ramalingam, S. Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma: From Biology to Treatment. Cancers 2023, 15, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.F.; Yu, Z.L. Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma Metastatic to the Mandible: A Unique Case Report and Literature Review. Chin. J. Dent. Res. 2023, 26, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mehr, J.P.; Blum, K.A.; Jones, W.S.; Maithel, N.; Citardi, M.J.; Canfield, S. A Case of Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma to the Maxillary Sinus Initially Presenting as Recurrent Epistaxis. JU Open Plus 2023, 1, e00074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navik, K.; Grover, S.; Garg, R.K.; Simrandeep; Garg, P. Unusual Metastasis of Renal Cell Carcinoma to Upper Gingiva: A Rare Case Report. Int. J. Life Sci. Biotechnol. Pharma Res. 2024, 13, 42–45. [Google Scholar]

- Bruckmann, M.; Brenet, E.; Boulagnon-Rombi, C.; Louvrier, A.; Maupriveze, C. Effectiveness of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in treating Kidney Cancer Oral Metastasis: A Case Report. J. Stomatol. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2024, 125, 101913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferri, C.A.; Nunes, J.S. Oral Metastasis of Clear Cell Renal Carcinoma Treated with Immunotherapy. Oral Oncol. Rep. 2024, 9, 100170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, C.H.; Cavalcante, I.L.; Ventura, J.V.L.; Cunha, J.L.S.; Tenório, J.R.; Oliveira, L.C.; Andrade, B.A.B. Oral Metastasis of Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma with Significant Facial Asymmetry. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2024, 137, e164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santerini Baez, F.; Pedreira Collazo, E.; Lamela, F.; Dornelles; Cosetti Oliver, L. Oral Metastasis of Renal Cell Carcinoma. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2024, 137, e179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzoi, G.; Rabelo, G.D.; Smiderle, F.; Lisboa, M.L.; Vieira, D.S.C.; Meurer, M.I.; Grando, L.J. Clear cell renal cell carcinoma metastasizing to the oral cavity: A diagnostic challenge of a case revealing an unusual clinical presentation. Oral Surg. 2024, 17, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kweon, H.T.; Yoo, J.S.; Hong, Y.T. Tongue metastasis from renal cell carcinoma: A rare case presentation. Ear Nose Throat J. 2024, 01455613231226038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barayobre, M.; Giani, N.; García Yllán, V.; García Muñiz, J.A. Clear cell renal cell carcinoma metastatic to the submaxillary gland, a rare event: Case report and literature review. Arch. Pathol. 2024, 4, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Liu, H.; Weng, B.; Hou, S. Case report: Tongue metastasis as an initial sign of clear cell renal cell carcinoma and its prognosis. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1473211. [Google Scholar]

- Nakako, Y.; Fujimoto, T.; Wada, H.; Yoshihama, N.; Kami, Y.; Fujii, S.; Kohashi, K.; Kumamaru, W.; Chikui, T.; Moriyama, M.; et al. Oral metastatic tumor (renal cell carcinoma) in maxillary gingiva: A case report and systematic review. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. Med. Pathol. 2024; in press. [Google Scholar]

| Authors | Year | Site | Gender | Age | First Sign of Disease | Another Metastasis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Huang and Yu [31] | 2023 | Gingiva | M | 48 | No | No metastasis |

| Justin P. Mehr et al. [32] | 2023 | Maxillary sinus | F | 74 | Yes | Lung, adrenal gland |

| Khushbu et al. [33] | 2024 | Gingiva | F | 52 | No | Lung |

| Bruckmann et al. [34] | 2024 | Palata mucosa | F | 60 | No | No metastasis |

| Camila et al. [35] | 2024 | Gingiva | M | 78 | No | No metastasis |

| Clara et al. [36] | 2024 | Mandibular bone | M | 56 | No | No metastasis |

| Florencia et al. [37] | 2024 | Maxillary alveolar ridge | F | 75 | No | Multiple body metastasis |

| Gabriely et al. [38] | 2024 | Buccal mucosa | M | 55 | Yes | Abdomen, bone |

| Hyeok Tae et al. [39] | 2024 | Tongue | M | 72 | No | Lung, bone |

| Dr. Matías et al. [40] | 2024 | Submandibular gland | M | 73 | No | No metastasis |

| Shuo Liu et al. [41] | 2025 | Tongue | M | 62 | Yes | Lung |

| Yusuke et al. [42] | 2025 | Gingiva | M | 79 | Yes | Lung |

| Habiba et al. (present study) | Buccal and palatal mucosa | F | 50 | Yes | Lung, adrenal gland, bone |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Habiba, U.; Chowdhury, A.F.M.A.; Ahmed, R.; Chowdhury, S.S.; Ferdoush, R.; Ise, K.; Rashid, H.u.; Rahman, Z.; Tanei, Z.-i.; Tanaka, S.; et al. Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Presenting a Maxillary Mucosal Lesion as a First Visible Sign of Disease: A Case Report and Review of Literature. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 938. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15070938

Habiba U, Chowdhury AFMA, Ahmed R, Chowdhury SS, Ferdoush R, Ise K, Rashid Hu, Rahman Z, Tanei Z-i, Tanaka S, et al. Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Presenting a Maxillary Mucosal Lesion as a First Visible Sign of Disease: A Case Report and Review of Literature. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(7):938. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15070938

Chicago/Turabian StyleHabiba, Umma, Abu Faem Mohammad Almas Chowdhury, Rafiz Ahmed, Saiyka S. Chowdhury, Raihanul Ferdoush, Koki Ise, Harun ur Rashid, Zillur Rahman, Zen-ichi Tanei, Shinya Tanaka, and et al. 2025. "Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Presenting a Maxillary Mucosal Lesion as a First Visible Sign of Disease: A Case Report and Review of Literature" Diagnostics 15, no. 7: 938. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15070938

APA StyleHabiba, U., Chowdhury, A. F. M. A., Ahmed, R., Chowdhury, S. S., Ferdoush, R., Ise, K., Rashid, H. u., Rahman, Z., Tanei, Z.-i., Tanaka, S., & Zaman, A.-U. (2025). Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Presenting a Maxillary Mucosal Lesion as a First Visible Sign of Disease: A Case Report and Review of Literature. Diagnostics, 15(7), 938. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15070938