Diagnostic and Clinical Impact of Double-Balloon Enteroscopy in Small-Bowel Inflammatory Lesions: A Retrospective Cohort Study in a Turkish Population

Abstract

1. Introduction

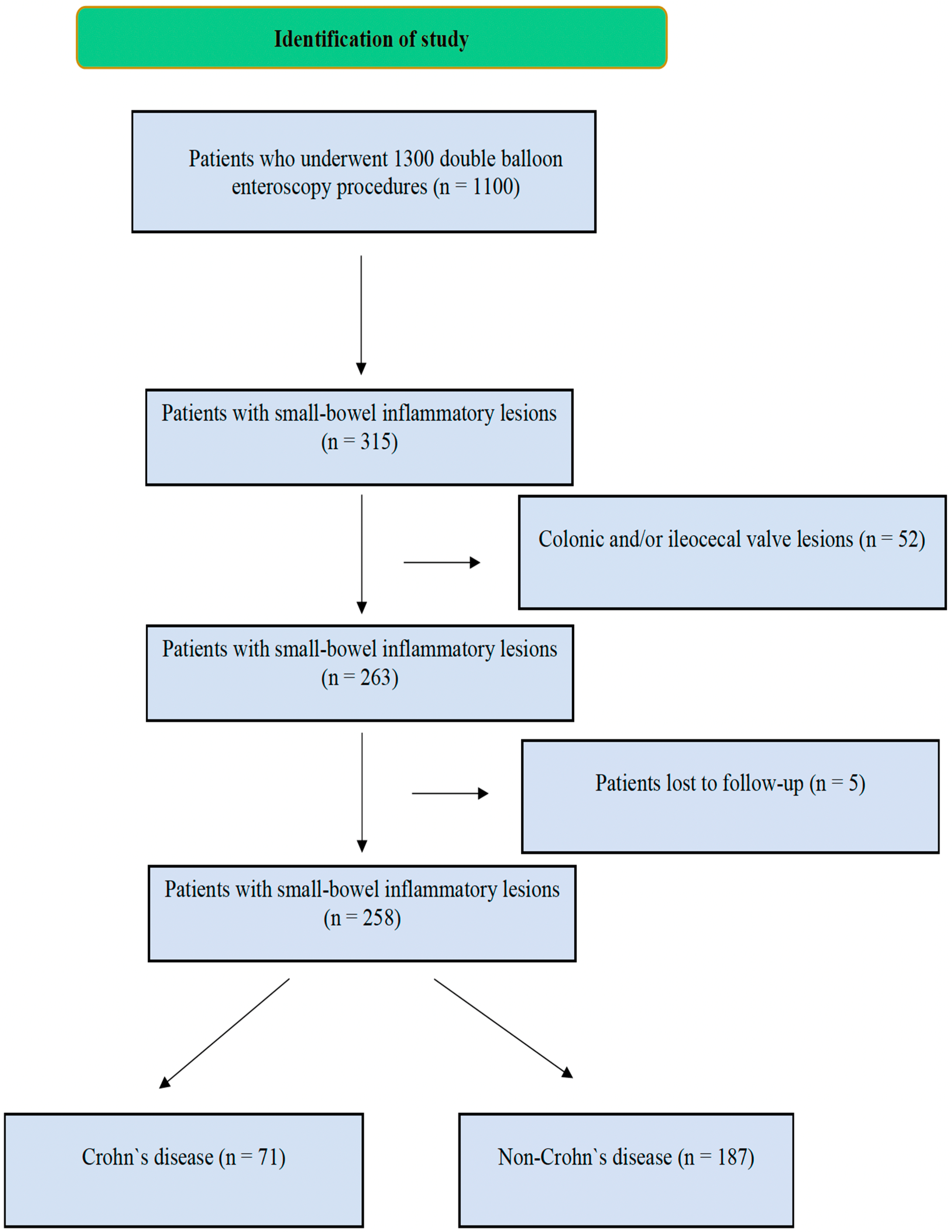

2. Methods

2.1. Data Collection and Study Design

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Demographics and Baseline Characteristics

3.2. Clinical Presentations and Symptoms

3.3. Comorbidities and Medication Use

3.4. Radiological and Endoscopic Findings

3.5. Comparison of Crohn’s Disease and Other Diagnoses

3.6. Histopathological and Final Diagnoses

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wu, F.-F.; Xie, Q.; Huang, X.-S.; Wang, W.-D.; Liao, Y.; Shi, J.; Sun, S.-B.; Bai, L.; Xie, F. Endoscopic Features and Clinical Characteristics of Ulcerations with Isolated Involvement of the Small Bowel. Turk. J. Gastroenterol. Off. J. Turk. Soc. Gastroenterol. 2021, 32, 401–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goenka, M.K.; Majumder, S.; Kumar, S.; Sethy, P.K.; Goenka, U. Single center experience of capsule endoscopy in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. World J. Gastroenterol. 2011, 17, 774–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahidi, N.C.; Ou, G.; Svarta, S.; Law, J.K.; Kwok, R.; Tong, J.; Lam, E.C.; Enns, R. Factors associated with positive findings from capsule endoscopy in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Off. Clin. Pract. J. Am. Gastroenterol. Assoc. 2012, 10, 1381–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gay, G.; Delvaux, M.; Frederic, M. Capsule endoscopy in non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs-enteropathy and miscellaneous, rare intestinal diseases. World J. Gastroenterol. 2008, 14, 5237–5244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, M.; Chen, Z.-H.; Li, M.; Zhang, X.; Chen, C.-X. Differentiation of Isolated Small Bowel Crohn’s Disease from Other Small Bowel Ulcerative Diseases: Clinical Features and Double-Balloon Enteroscopy Characteristics. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2022, 2022, 5374780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esaki, M.; Matsumoto, T.; Ohmiya, N.; Washio, E.; Morishita, T.; Sakamoto, K.; Abe, H.; Yamamoto, S.; Kinjo, T.; Togashi, K.; et al. Capsule endoscopy findings for the diagnosis of Crohn’s disease: A nationwide case-control study. J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 54, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belhassine, M.; Dragean, C.; Dano, H.; Moreels, T.G. Cryptogenic multifocal ulcerative stenosing enteritis (CMUSE) diagnosed by retrograde motorized spiral enteroscopy. Acta Gastro-Enterol. Belg. 2022, 85, 527–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orjollet-Lecoanet, C.; Ménard, Y.; Martins, A.; Crombé-Ternamian, A.; Cotton, F.; Valette, P.J. CT enteroclysis for detection of small bowel tumors. J. Radiol. 2000, 81, 618–627. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Huang, Z.; Liu, X.; Yang, F.; Wang, G.; Ge, N.; Wang, S.; Guo, J.; Sun, S. Diagnostic efficacy of double-balloon enteroscopy in patients with suspected isolated small bowel Crohn’s disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 2020, 20, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolu, S.; Onem, S.; Htway, Z.; Hajıyev, F.; Bilgen, A.; Binicier, H.C.; Kalemoglu, E.; Sagol, O.; Akarsu, M. Endoscopic and histological characteristics of small bowel tumors diagnosed by double-balloon enteroscopy. Clin. Endosc. 2023, 56, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolu, S.; Arayici, M.E.; Onem, S.; Buyuktorun, I.; Dongelli, H.; Bengi, G.; Akarsu, M. Evaluation of double-balloon enteroscopy in the management of type 1 small bowel vascular lesions (angioectasia): A retrospective cohort study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2025, 25, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yalçın, E.; Döngelli, H.; Dolu, S.; Akarsu, M. Eosinophilic jejunitis presenting as acute abdomen with eosinophilic ascites. BMJ Case Rep. 2024, 17, e261123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Huang, L.-Y.; Cui, J.; Wu, C.-R. Effect of Double-Balloon Enteroscopy on Diagnosis and Treatment of Small-Bowel Diseases. Chin. Med. J. (Engl.) 2018, 131, 1321–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolu, S.; Arayici, M.E.; Onem, S.; Buyuktorun, I.; Dongelli, H.; Bengi, G.; Akarsu, M. Effectiveness of Double Balloon Enteroscopy in the Diagnosis and Treatment of Small Bowel Varices. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.-J.; Wang, Y.; Xu, X.-M.; Su, J.-W.; Jiang, W.-Y.; Jiang, J.-X.; Lin, L.; Zhang, D.-Q.; Ding, J.; Chen, L.; et al. Capsule endoscopy and single-balloon enteroscopy in small bowel diseases: Competing or complementary? World J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 22, 10625–10630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catassi, G.; Marmo, C.; Gasbarrini, A.; Riccioni, M.E. Role of Device-Assisted Enteroscopy in Crohn’s Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 3919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arulanandan, A.; Dulai, P.S.; Singh, S.; Sandborn, W.J.; Kalmaz, D. Systematic review: Safety of balloon assisted enteroscopy in Crohn’s disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 22, 8999–9011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, S.R.; Kim, J.-O.; Byeon, J.-S.; Yang, D.-H.; Ko, B.M.; Goong, H.J.; Jang, H.J.; Park, S.J.; Kim, E.R.; Hong, S.N.; et al. Enteroscopy in Crohn’s Disease: Are There Any Changes in Role or Outcomes Over Time? A KASID Multicenter Study. Gut Liver 2021, 15, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, A.; Nachbar, L.; Schneider, M.; Neumann, M.; Ell, C. Push-and-pull enteroscopy using the double-balloon technique: Method of assessing depth of insertion and training of the enteroscopy technique using the Erlangen Endo-Trainer. Endoscopy 2005, 37, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, H.; Kita, H.; Sunada, K.; Hayashi, Y.; Sato, H.; Yano, T.; Iwamoto, M.; Sekine, Y.; Miyata, T.; Kuno, A.; et al. Clinical outcomes of double-balloon endoscopy for the diagnosis and treatment of small-intestinal diseases. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Off. Clin. Pract. J. Am. Gastroenterol. Assoc. 2004, 2, 1010–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Assche, G.; Dignass, A.; Panes, J.; Beaugerie, L.; Karagiannis, J.; Allez, M.; Ochsenkühn, T.; Orchard, T.; Rogler, G.; Louis, E.; et al. The second European evidence-based Consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn’s disease: Definitions and diagnosis. J. Crohns Colitis 2010, 4, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.P.; Jang, H.J.; Kae, S.H.; Lee, J.G.; Kwon, J.H. Indication, Location of the Lesion, Diagnostic Yield, and Therapeutic Yield of Double-Balloon Enteroscopy: Seventeen Years of Experience. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, L.; Liao, Z.; Jiang, Y.-P.; Li, Z.-S. Indications, detectability, positive findings, total enteroscopy, and complications of diagnostic double-balloon endoscopy: A systematic review of data over the first decade of use. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2011, 74, 563–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heine, G.D.; Hadithi, M.; Groenen, M.J.; Kuipers, E.J.; Jacobs, M.A.; Mulder, C.J. Double-balloon enteroscopy: Indications, diagnostic yield, and complications in a series of 275 patients with suspected small-bowel disease. Endoscopy 2006, 38, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tun, G.S.Z.; Rattehalli, D.; Sanders, D.S.; McAlindon, M.E.; Drew, K.; Sidhu, R. Clinical utility of double-balloon enteroscopy in suspected Crohn’s disease: A single-centre experience. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 28, 820–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Z.-Z.; Hu, Y.-B.; Xiao, S.-D. Capsule endoscopy in diagnosis of small bowel Crohn’s disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 2004, 10, 1349–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Guo, Q.; Zhao, J.; Liu, M.; Liao, G.; Chen, N.; Tian, D.; Wu, X. Multidetector CT Enterography versus Double-Balloon Enteroscopy: Comparison of the Diagnostic Value for Patients with Suspected Small Bowel Diseases. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2016, 2016, 5172873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manes, G.; Imbesi, V.; Ardizzone, S.; Cassinotti, A.; Pallotta, S.; Porro, G.B. Use of double-balloon enteroscopy in the management of patients with Crohn’s disease: Feasibility and diagnostic yield in a high-volume centre for inflammatory bowel disease. Surg. Endosc. 2009, 23, 2790–2795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, I.I.; Thorndal, C.; Manzoor, M.S.; Parsons, N.; Noble, C.; Huhulea, C.; Koulaouzidis, A.; Arasaradnam, R.P. The Diagnostic Accuracy of Colon Capsule Endoscopy in Inflammatory Bowel Disease-A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshitani, N.; Yukawa, T.; Yamagami, H.; Inagawa, M.; Kamata, N.; Watanabe, K.; Jinno, Y.; Fujiwara, Y.; Higuchi, K.; Arakawa, T. Evaluation of deep small bowel involvement by double-balloon enteroscopy in Crohn’s disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2006, 101, 1484–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Duodenum (n = 31) | Jejunum (n = 63) | Ileum (n = 82) | Panenteritis (n = 82) | Total (n = 258) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD | 57.1 ± 16.8 | 52.7 ± 17.2 | 46.6 ± 17.5 | 42.0 ± 15.6 | 48.2 ± 17.3 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 12 (38.7) | 27 (42.9) | 30 (36.6) | 31 (37.8) | 100 (38.8) |

| Complaint at admission, n (%) | |||||

| Abdominal pain | 10 (32.3) | 35 (55.6) | 36 (43.9) | 42 (51.2) | 123 (47.7) |

| Diarrhea | 5 (16.1) | 12 (19.0) | 31 (37.8) | 34 (41.5) | 82 (31.8) |

| Nausea | 5 (16.1) | 2 (3.2) | 1 (1.2) | 6 (7.3) | 14 (5.4) |

| Bleeding | 8 (25.8) | 10 (15.9) | 16 (19.5) | 10 (12.2) | 44 (17.1) |

| Steatorrhea | 2 (6.5) | 3 (4.8) | 3 (3.7) | 9 (11.0) | 17 (6.6) |

| Weight loss | 6 (19.4) | 10 (19.4) | 8 (9.8) | 13 (15.9) | 37 (14.3) |

| Anemia | 5 (16.1) | 10 (15.9) | 9 (11.0) | 7 (8.5) | 31 (12.0) |

| Ileus/subileus | 0 (0) | 3 (4.8) | 15 (18.3) | 9 (11.0) | 27 (10.5) |

| Fever | 1 (3.2) | 1 (1.6) | 0 (0) | 3 (3.7) | 5 (1.9) |

| Comorbidity, n (%) | |||||

| Hypertension | 10 (32.3) | 25 (39.7) | 17 (20.7) | 14 (17.1) | 66 (25.6) |

| DM | 4 (12.9) | 12 (19) | 11 (13.4) | 7 (8.5) | 34 (13.2) |

| Dyslipidemia | 2 (6.5) | 4 (6.3) | 6 (7.3) | 1 (1.2) | 13 (5.0) |

| CAD | 5 (16.1) | 5 (7.9) | 6 (7.3) | 3 (3.7) | 19 (7.4) |

| Heart failure | 0 (0) | 2 (3.2) | 3 (3.7) | 0 (0) | 5 (1.9) |

| Afib | 2 (6.5) | 4 (6.3) | 1 (1.2) | 2 (2.4) | 9 (3.5) |

| COPD | 1 (3.2) | 3 (4.8) | 5 (6.1) | 1 (1.2) | 10 (3.9) |

| CKD | 1 (3.2) | 1 (1.6) | 2 (2.4) | 0 (0) | 4 (1.6) |

| Immunodeficiency | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.2) | 4 (4.9) | 5 (1.9) |

| Hypothyroidism | 3 (9.7) | 2 (3.2) | 2 (2.4) | 1 (1.2) | 8 (3.1) |

| Malignancy | 6 (19.4) | 11 (17.5) | 7 (8.5) | 6 (7.3) | 30 (11.6) |

| Liver cirrhosis | 0 (0) | 1 (1.6) | 2 (2.4) | 1 (1.2) | 4 (1.6) |

| CTD | 0 (0) | 3 (4.8) | 5 (6.1) | 7 (8.5) | 15 (5.8) |

| Medication, n (%) | |||||

| NSAIDs | 5 (16.1) | 13 (20.6) | 25 (28.0) | 24 (29.3) | 65 (25.2) |

| ASA | 6 (19.4) | 9 (14.3) | 11 (13.4) | 4 (4.9) | 30 (11.6) |

| SSRIs | 1 (3.2) | 2 (3.2) | 3 (3.3) | 1 (1.2) | 7 (2.7) |

| NOACs | 1 (3.2) | 3 (4.8) | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0) | 5 (1.9) |

| Warfarin | 0 (0) | 1 (1.6) | 1 (1.2) | 2 (2.4) | 4 (1.6) |

| Glucocorticosteroids | 0 (0) | 1 (1.6) | 3 (3.7) | 2 (2.4) | 6 (2.3) |

| Metformin | 1 (3.2) | 6 (9.5) | 0 (0) | 3 (3.7) | 10 (3.9) |

| History of GIS surgery, n (%) | 2 (6.5) | 1 (1.6) | 8 (9.8) | 1 (1.2) | 12 (4.6) |

| CT findings, n (%) | |||||

| Not performed | 7 (22.6) | 7 (11.1) | 15 (18.3) | 16 (19.5) | 45 (17.4) |

| Normal | 9 (29.0) | 14 (22.2) | 27 (32.9) | 28 (34.1) | 78 (30.2) |

| Wall thickness | 6 (19.4) | 22 (34.9) | 23 (28.0) | 30 (36.6) | 81 (31.4) |

| Mass appearance | 5 (16.1) | 17 (27.0) | 7 (8.5) | 2 (2.4) | 31 (12.0) |

| Bleeding | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.2) | 1 (0.4) |

| Lymphadenopathy | 0 (0) | 2 (3.2) | 2 (2.4) | 2 (2.4) | 6 (2.3) |

| Ileus/subileus | 4 (12.9) | 1 (1.6) | 8 (9.8) | 3 (3.7) | 16 (6.2) |

| Double-balloon enteroscopy findings, n (%) | |||||

| Superficial changes | 4 (12.9) | 14 (22.2) | 21 (25.6) | 21 (25.6) | 60 (23.3) |

| Edema | 7 (22.6) | 16 (25.4) | 7 (8.5) | 27 (32.9) | 57 (22.1) |

| Ulcer | 17 (54.8) | 25 (39.7) | 47 (57.3) | 27 (32.9) | 116 (45.0) |

| Stenosis | 3 (9.7) | 8 (12.7) | 7 (8.5) | 7 (8.5) | 25 (9.7) |

| Crohn’s Disease (n = 71) | Non-Crohn’s Disease (n = 187) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD | 40.9 ± 14.7 | 50.9 ± 17.5 | <0.001 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 26 (36.6) | 74 (39.6) | 0.664 |

| Complaint at admission, n (%) | |||

| Abdominal pain | 49 (69.0) | 74 (39.6) | <0.001 |

| Diarrhea | 37 (52.1) | 45 (24.1) | <0.001 |

| Nausea | 2 (2.8) | 12 (6.4) | 0.362 |

| Bleeding | 2 (2.8) | 42 (22.5) | <0.001 |

| Steatorrhea | 4 (5.6) | 13 (7.0) | 0.703 |

| Weight loss | 11 (15.5) | 26 (13.9) | 0.745 |

| Anemia | 3 (4.2) | 28 (15.0) | 0.018 |

| Ileus/subileus | 13 (18.3) | 14 (7.5) | 0.011 |

| Fever | 0 (0) | 5 (2.7) | 0.327 * |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |||

| Hypertension | 9 (12.7) | 57 (30.5) | 0.003 |

| DM | 4 (5.6) | 30 (16.0) | 0.027 |

| Dyslipidemia | 2 (2.8) | 11 (5.9) | 0.524 |

| CAD | 2 (2.8) | 17 (9.1) | 0.085 |

| Heart failure | 0 (0) | 5 (2.7) | 0.327 * |

| Afib | 0 (0) | 9 (4.8) | 0.067 * |

| COPD | 2 (2.8) | 8 (4.3) | 0.732 |

| CKD | 0 (0) | 4 (2.1) | 0.578 * |

| Immunodeficiency | 0 (0) | 5 (2.7) | 0.327 * |

| Hypothyroidism | 1 (1.4) | 7 (3.7) | 0.452 * |

| Malignancy | 4 (5.6) | 26 (13.9) | 0.064 |

| Liver cirrhosis | 1 (1.4) | 3 (1.6) | 0.909 * |

| CTD | 8 (11.3) | 7 (3.7) | 0.021 |

| Medications, n (%) | |||

| NSAIDs | 14 (19.7) | 51 (27.3) | 0.212 |

| ASA | 8 (11.3) | 22 (11.8) | 0.911 |

| SSRIs | 1 (1.4) | 6 (3.2) | 0.677 * |

| NOACs | 0 (0) | 5 (2.7) | 0.327 * |

| Warfarin | 0 (0) | 4 (2.1) | 0.578 * |

| Glucocorticosteroids | 1 (1.4) | 5 (2.7) | 0.889 * |

| Metformin | 2 (2.8) | 8 (4.3) | 0.732 |

| History of GIS surgery, n (%) | 3 (4.2) | 9 (4.8) | 0.841 |

| Intestinal involvement, n (%) | N/A | ||

| Duodenum (only) | 3 (4.2) | 28 (15.0) | |

| Jejunum (only) | 5 (7.0) | 58 (31.0) | |

| Ileum (only) | 39 (54.9) | 43 (23.0) | |

| Duodenum and jejunum | 2 (2.8) | 26 (13.9) | |

| Duodenum and ileum | 2 (2.8) | 6 (3.2) | |

| Jejunum and ileum | 13 (18.3) | 18 (9.6) | |

| Panenteritis | 7 (9.9) | 8 (4.3) | |

| CT findings, n (%) | N/A | ||

| Not performed | 9 (12.7) | 36 (19.3) | |

| Normal | 19 (26.8) | 59 (31.6) | |

| Wall thickness | 29 (40.8) | 52 (27.8) | |

| Mass appearance | 3 (4.2) | 28 (15.0) | |

| Bleeding | 0 (0) | 1 (0.5) | |

| Lymphadenopathy | 3 (4.2) | 3 (1.6) | |

| Ileus/subileus | 8 (11.4) | 8 (4.3) | |

| Double-balloon enteroscopy findings, n (%) | |||

| Superficial changes | 10 (14.1) | 50 (26.7) | 0.032 |

| Edema | 11 (15.5) | 46 (24.6) | 0.115 |

| Ulcer | 43 (60.3) | 73 (39.0) | 0.002 |

| Stenosis | 7 (9.9) | 18 (9.6) | 0.955 |

| Final Diagnosis | n = 258 | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Crohn’s disease | 71 | 27.5% |

| Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced enteropathy | 31 | 12.0% |

| Celiac | 24 | 9.3% |

| Radiation enteritis | 4 | 1.6% |

| Infection | 6 | 2.3% |

| Ischemia | 3 | 1.2% |

| Autoimmune enteropathy | 5 | 1.9% |

| Behcet’s disease | 1 | 0.4% |

| Lymphoma | 8 | 3.1% |

| Malignancy a | 41 | 15.9% |

| Eosinophilic enteritis | 8 | 3.1% |

| Vasculitis | 5 | 1.9% |

| Graft-versus-host disease | 1 | 0.4% |

| Lymphangiectasia | 9 | 3.5% |

| Amyloidosis | 3 | 1.2% |

| Non-specific | 38 | 14.7% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dolu, S.; Arayici, M.E.; Onem, S.; Dongelli, H.; Akarsu, M. Diagnostic and Clinical Impact of Double-Balloon Enteroscopy in Small-Bowel Inflammatory Lesions: A Retrospective Cohort Study in a Turkish Population. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 661. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15060661

Dolu S, Arayici ME, Onem S, Dongelli H, Akarsu M. Diagnostic and Clinical Impact of Double-Balloon Enteroscopy in Small-Bowel Inflammatory Lesions: A Retrospective Cohort Study in a Turkish Population. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(6):661. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15060661

Chicago/Turabian StyleDolu, Suleyman, Mehmet Emin Arayici, Soner Onem, Huseyin Dongelli, and Mesut Akarsu. 2025. "Diagnostic and Clinical Impact of Double-Balloon Enteroscopy in Small-Bowel Inflammatory Lesions: A Retrospective Cohort Study in a Turkish Population" Diagnostics 15, no. 6: 661. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15060661

APA StyleDolu, S., Arayici, M. E., Onem, S., Dongelli, H., & Akarsu, M. (2025). Diagnostic and Clinical Impact of Double-Balloon Enteroscopy in Small-Bowel Inflammatory Lesions: A Retrospective Cohort Study in a Turkish Population. Diagnostics, 15(6), 661. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15060661