Accuracy of COuGH RefluX Score as a Predictor of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) in Mexican Patients with Chronic Laryngopharyngeal Symptoms: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

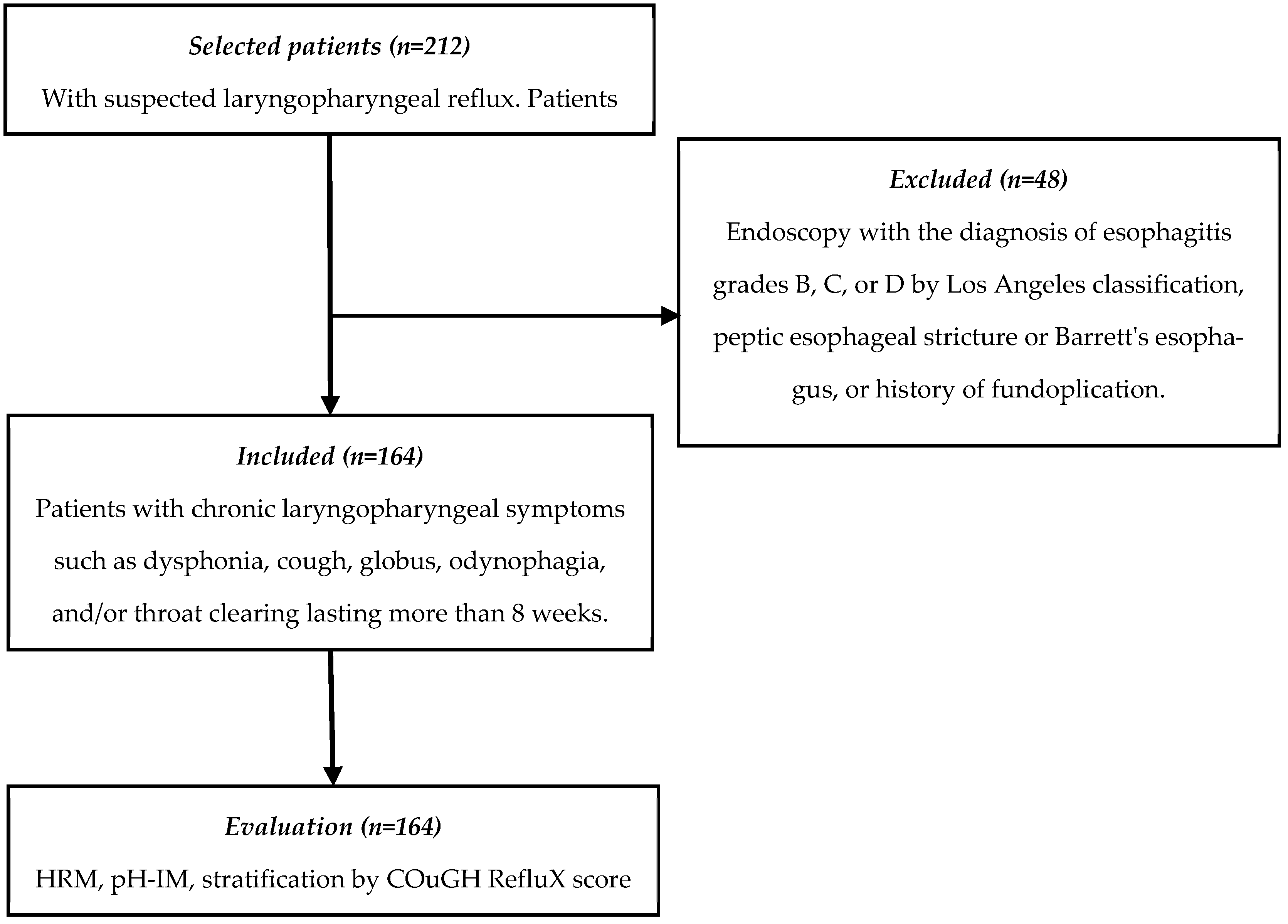

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Ethical Considerations

2.3. Patient Eligibility Criteria

2.4. Clinical, Endoscopic, and Gastrointestinal Physiology Evaluation of Participants

2.5. Sample Size

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics of the Population

3.2. GERD Diagnosis and Risk Factors

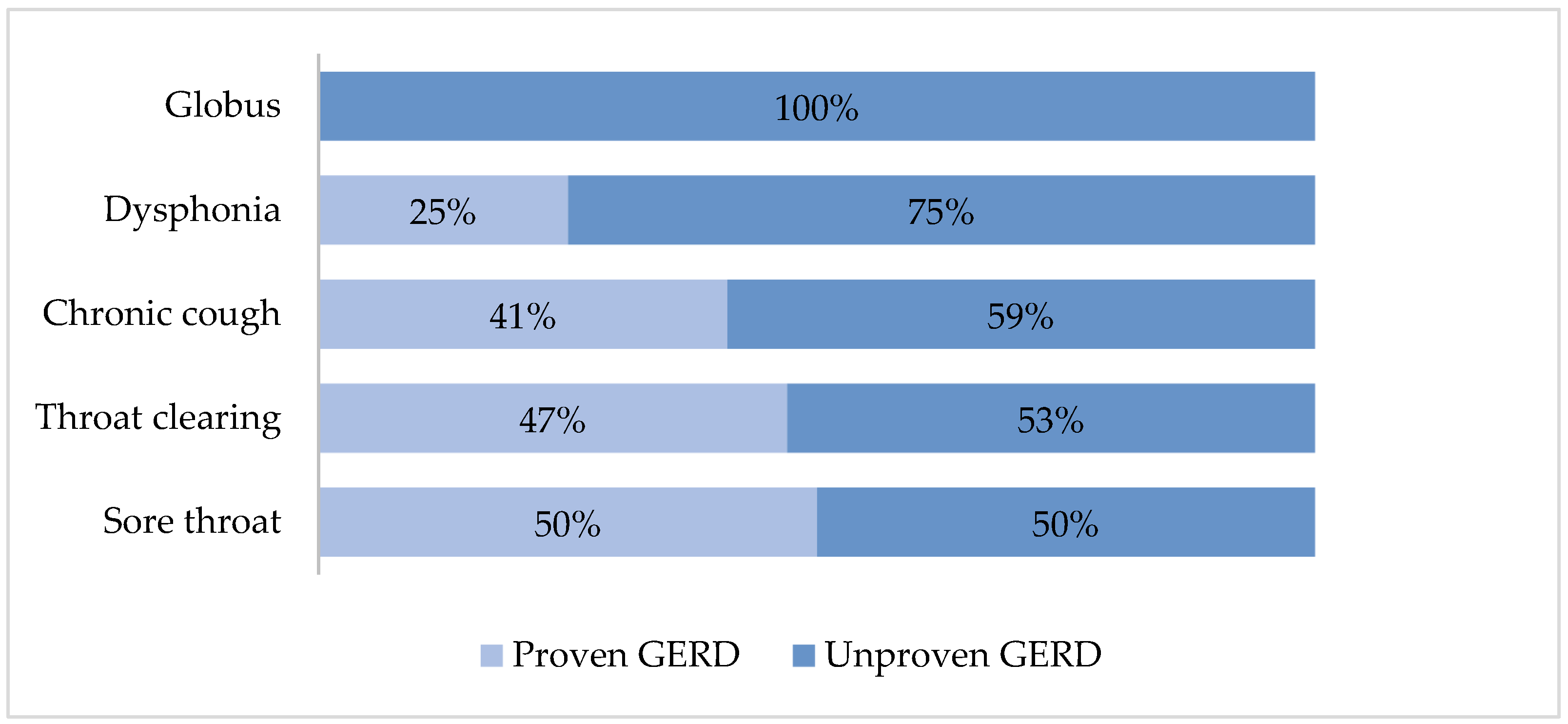

3.3. Diagnosis of Proven GERD According to the Reported Laryngopharyngeal Symptoms

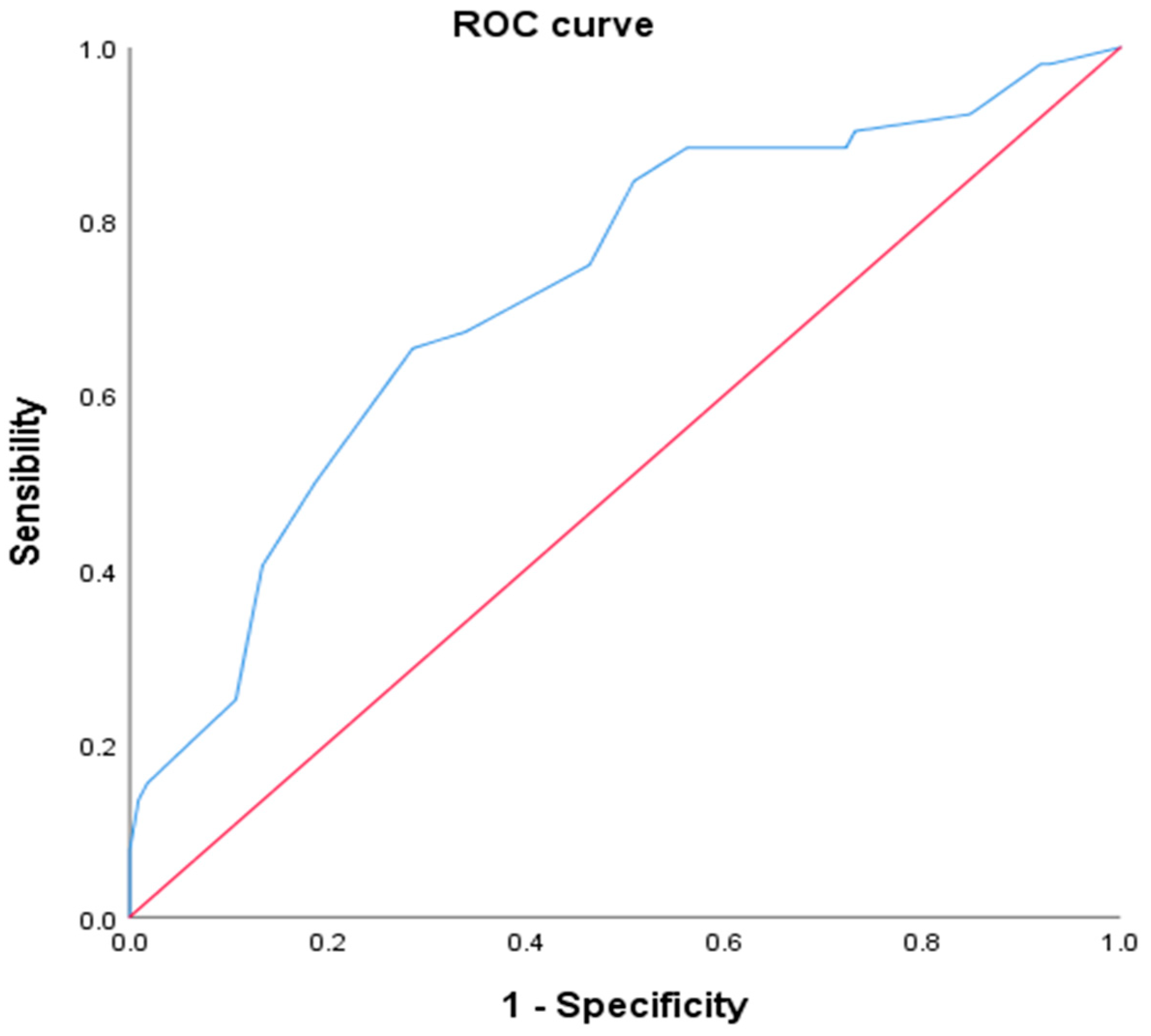

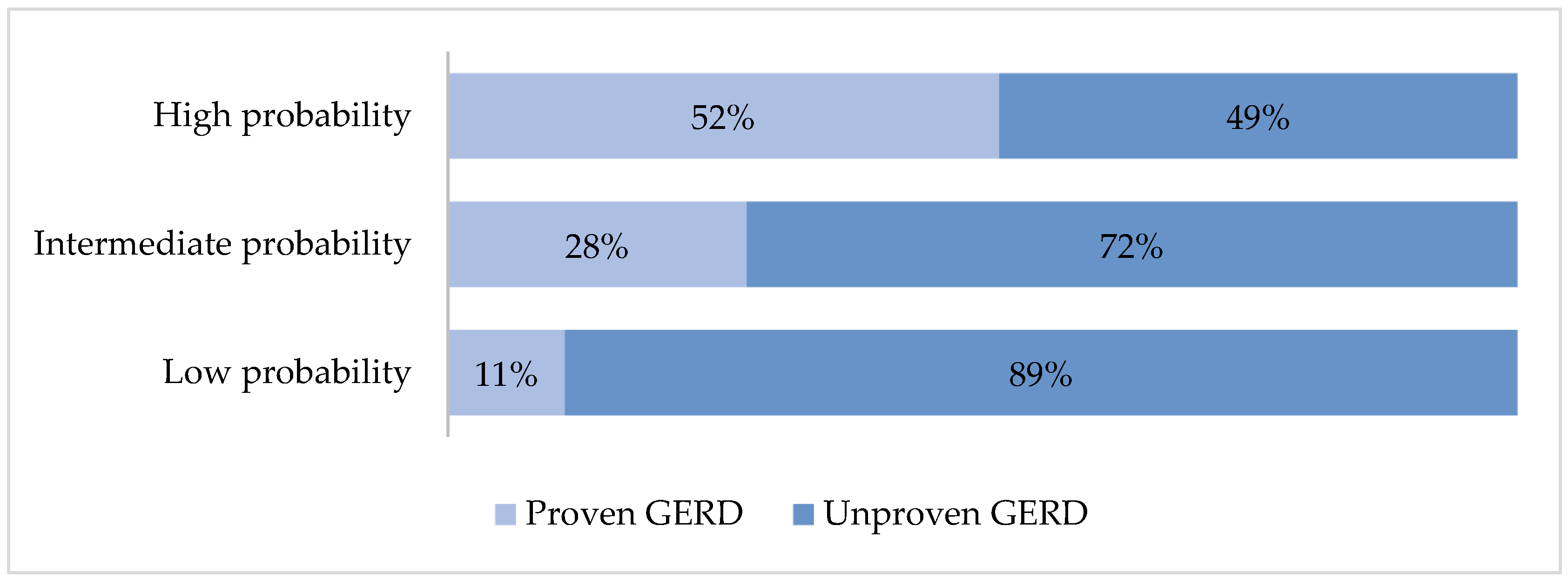

3.4. Proven GERD Prediction Using Cough Reflux Score

3.5. Post Hoc Analysis Excluding Hiatal Hernia

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nirwan, J.S.; Hasan, S.S.; Babar, Z.U.; Conway, B.R.; Ghori, M.U. Global Prevalence and Risk Factors of Gastro-oesophageal Reflux Disease (GORD): Systematic Review with Meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 5814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katzka, D.A.; Pandolfino, J.E.; Kahrilas, P.J. Phenotypes of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: Where Rome, Lyon, and Montreal Meet. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 18, 767–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lechien, J.R.; Akst, L.M.; Hamdan, A.L.; Schindler, A.; Karkos, P.D.; Barillari, M.R.; Calvo-Henriquez, C.; Crevier-Buchman, L.; Finck, C.; Eun, Y.-G.; et al. Evaluation and Management of Laryngopharyngeal Reflux Disease: State of the Art Review. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2019, 160, 762–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosli, M.; Alkhathlan, B.; Abumohssin, A.; Merdad, M.; Alherabi, A.; Marglani, O.; Jawa, H.; Alkhatib, T.; Marzouki, H.Z. Prevalence and clinical predictors of LPR among patients diagnosed with GERD according to the reflux symptom index questionnaire. Saudi J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 24, 236–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muddaiah, D.; Prashanth, V.; Vybhavi, M.K.; Srinivas, V.; Lavanya, M. Role of Reflux Symptom Index and Reflux Finding Score in Diagnosing Laryngopharyngeal Reflux: A Prospective Study. Indian J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2023, 75, 777–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirti, Y.K. Reflux Finding Score (RFS) a Quantitative Guide for Diagnosis and Treatment of Laryngopharyngeal Reflux. Indian J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2018, 70, 362–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, P.O.; Dunbar, K.B.; Schnoll-Sussman, F.H.; Greer, K.B.; Yadlapati, R.; Spechler, S.J. ACG Clinical Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 117, 27–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahrilas, P.J.; Altman, K.W.; Chang, A.B.; Field, S.K.; Harding, S.M.; Lane, A.P.; Lim, K.; McGarvey, L.; Smith, J.; Irwin, R.S.; et al. Chronic Cough Due to Gastroesophageal Reflux in Adults: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest 2016, 150, 1341–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krause, A.J.; Kaizer, A.M.; Carlson, D.A.; Chan, W.W.; Chen, C.L.; Gyawali, C.P.; Jenkins, A.; Pandolfino, J.E.; Polamraju, V.; Wong, M.-W.; et al. Validated Clinical Score to Predict Gastroesophageal Reflux in Patients with Chronic Laryngeal Symptoms: COuGH RefluX. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 22, 1200–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahrilas, P.J.; Bredenoord, A.J.; Fox, M.; Gyawali, C.P.; Roman, S.; Smout, A.J.; Pandolfino, J.E.; International High Resolution Manometry Working Group. The Chicago Classification of esophageal motility disorders, v3.0. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2015, 27, 160–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadlapati, R.; Kahrilas, P.J.; Fox, M.R.; Bredenoord, A.J.; Prakash Gyawali, C.; Roman, S.; Babaei, A.; Mittal, R.K.; Rommel, N.; Savarino, E. Esophageal motility disorders on high-resolution manometry: Chicago classification version 4.0((c)). Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2021, 33, e14058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durazzo, M.; Lupi, G.; Cicerchia, F.; Ferro, A.; Barutta, F.; Beccuti, G.; Gruden, G.; Pellicano, R. Extra-Esophageal Presentation of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: 2020 Update. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Dong, R.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, M.; Xu, X.; Yu, L.; Qiu, Z. Tracheobronchial-esophageal reflex initiates esophageal hypersensitivity and aggravates cough hyperreactivity in guinea pigs with esophageal acid infusion. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2022, 301, 103890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Ma, Y.; Chen, Y. GERD-related chronic cough: Possible mechanism, diagnosis and treatment. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 1005404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, K.F.; McGarvey, L.; Song, W.J.; Chang, A.B.; Lai, K.; Canning, B.J.; Birring, S.S.; Smith, J.A.; Mazzone, S.B. Cough hypersensitivity and chronic cough. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2022, 8, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochizuki, N.; Fujita, T.; Kobayashi, M.; Yamazaki, Y.; Terao, S.; Sanuki, T.; Okada, A.; Adachi, M.; Murakami, M.; Arisaka, Y.; et al. Factors associated with presenting erosive esophagitis symptoms in health checkup subjects: A prospective, multicenter cohort study. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0196848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, S.; Wang, S.; Niu, S.; Zhang, M.; Shi, C.; Qiu, Z.; Xu, X.; Yu, L. Sensitivity and specificity of combination of Hull airway reflux questionnaire and gastroesophageal reflux disease questionnaire in identifying patients with gastroesophageal reflux-induced chronic cough. Ann. Transl. Med. 2020, 8, 1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lien, H.C.; Lee, P.H.; Wang, C.C. Diagnosis of Laryngopharyngeal Reflux: Past, Present, and Future—A Mini-Review. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, A.J.; Yadlapati, R. Review article: Diagnosis and management of laryngopharyngeal reflux. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2024, 59, 616–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyawali, C.P.; Yadlapati, R.; Fass, R.; Katzka, D.; Pandolfino, J.; Savarino, E.; Sifrim, D.; Spechler, S.; Zerbib, F.; Fox, M.R.; et al. Updates to the modern diagnosis of GERD: Lyon consensus 2.0. Gut 2024, 73, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tack, J.; Pandolfino, J.E. Pathophysiology of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Gastroenterology 2018, 154, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paris, S.; Ekeanyanwu, R.; Jiang, Y.; Davis, D.; Spechler, S.J.; Souza, R.F. Obesity and its effects on the esophageal mucosal barrier. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2021, 321, G335–G343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lechien, J.R.; Bobin, F.; Muls, V.; Saussez, S.; Hans, S. Laryngopharyngeal Reflux Disease is More Severe in Obese Patients: A Prospective Multicenter Study. Laryngoscope 2021, 131, E2742–E2748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.X.; Han, C.S.; Xue, J.R.; Han, Z.F.; Xin, H. Esophageal hiatal hernia: Risk, diagnosis and management. Expert Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 12, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witarto, A.P.; Witarto, B.S.; Pramudito, S.L.; Ratri, L.C.; Wairooy, N.A.P.; Konstantin, T.; Putra, A.J.E.; Wungu, C.D.K.; Mufida, A.Z.; Gusnanto, A. Risk factors and 26-years worldwide prevalence of endoscopic erosive esophagitis from 1997 to 2022: A meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 15249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arinze, J.T.; de Roos, E.W.; Karimi, L.; Verhamme, K.M.C.; Stricker, B.H.; Brusselle, G.G. Prevalence and incidence of, and risk factors for chronic cough in the adult population: The Rotterdam Study. ERJ Open Res. 2020, 6, 00300-2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechien, J.R.; Bobin, F.; Muls, V.; Eisendrath, P.; Horoi, M.; Thill, M.P.; Dequanter, D.; Durdurez, J.-P.; Rodriguez, A.; Saussez, S. Gastroesophageal reflux in laryngopharyngeal reflux patients: Clinical features and therapeutic response. Laryngoscope 2020, 130, E479–E489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerbib, F.; Rommel, N.; Pandolfino, J.; Gyawali, C.P. ESNM/ANMS Review. Diagnosis and management of globus sensation: A clinical challenge. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2020, 32, e13850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevalainen, P.; Walamies, M.; Kruuna, O.; Arkkila, P.; Aaltonen, L.M. Supragastric belch may be related to globus symptom-a prospective clinical study. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2016, 28, 680–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvenpaa, P.; Arkkila, P.; Aaltonen, L.M. Globus pharyngeus: A review of etiology, diagnostics, and treatment. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2018, 275, 1945–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, S.C.; Burgess, S. Appraising the causal role of smoking in multiple diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis of Mendelian randomization studies. EBioMedicine 2022, 82, 104154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sykes, D.L.; Crooks, M.G.; Hart, S.P.; Jackson, W.; Gallagher, J.; Morice, A.H. Investigating the diagnostic utility of high-resolution oesophageal manometry in patients with refractory respiratory symptoms. Respir. Med. 2022, 202, 106985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Overall n = 164 | Esophageal and Laryngopharyngeal Symptoms n = 123 | Isolated Laryngopharyngeal Symptoms n = 41 | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (IQR) | 54 (20.5) | 56 (23) | 53 (21) | 0.486 |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.925 | |||

| Men | 59 (36) | 44 (36) | 15 (37) | |

| Women | 105 (64) | 79 (64) | 26 (63) | |

| T2D, n (%) | 32 (20) | 23 (19) | 9 (22) | 0.649 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 47 (29) | 39 (32) | 8 (19) | 0.135 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 35 (21) | 28 (23) | 7 (17) | 0.441 |

| BMI, kg/m2 (mean ± SD) | 26.1 (5.9) | 26.2 (6.6) | 25.7 (5.1) | 0.001 * |

| Overweight or obesity, n (%) | 123 (75) | 77 (63) | 23 (56) | 0.460 |

| Hiatal hernia on endoscopy, n (%) | 86 (52) | 75 (61) | 11 (27) | <0.001 * |

| Hiatal hernia on HRM, n (%) | 41 (25) | 38 (31) | 3 (8) | 0.009 * |

| Esophageal motility pattern, n (%) | 0.466 | |||

| Normal esophageal motility | 126 (77) | 92 (75) | 34 (83) | |

| IEM | 35 (21) | 29 (24) | 6 (15) | |

| Absent contractility | 3 (2) | 2 (1) | 1 (2) | |

| Laryngopharyngeal symptoms, n (%) | ||||

| Chronic cough | 118 (72) | 85 (69) | 33 (80) | 0.160 |

| Globus | 47 (29) | 29 (24) | 18 (44) | 0.013 * |

| Throat clearing | 57 (35) | 48 (39) | 9 (22) | 0.047 * |

| Dysphonia | 40 (24) | 29 (24) | 11 (27) | 0.675 |

| Sore throat | 24 (15) | 18 (15) | 6 (15) | 1.000 |

| Proven GERD | 52 (32) | 45 (37) | 7 (17) | 0.020 * |

| Proven GERD n = 52 | Unproven GERD n = 112 | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (IQR) | 56 (23) | 53 (21) | 0.382 |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.805 | ||

| Men | 18 (35) | 41 (37) | |

| Women | 34 (65) | 71 (63) | |

| T2D, n (%) | 15 (29) | 16 (15) | 0.040 * |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 17 (33) | 30 (27) | 0.436 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 15 (29) | 20 (18) | 0.110 |

| BMI, kg/m2 (mean ± SD) | 27.8 (6.2) | 25.2 (5.7) | 0.002 * |

| Overweight or obesity, n (%) | 41 (79) | 59 (53) | 0.001 * |

| Hiatal hernia on endoscopy, n (%) | 35 (67) | 51 (45) | 0.009 * |

| Hiatal hernia on HRM, n (%) | 16 (31) | 25 (22) | 0.033 * |

| Esophageal motility pattern, n (%) | 0.904 | ||

| Normal esophageal motility | 41 (79) | 85 (76) | |

| Ineffective esophageal motility | 10 (19) | 25 (22) | |

| Absent contractility | 1 (2) | 2 (2) | |

| Laryngopharyngeal symptoms, n (%) | |||

| Chronic cough | 37 (71) | 81 (72) | 0.877 |

| Globus | 7 (13) | 40 (36) | 0.003 * |

| Throat clearing | 17 (33) | 40 (36) | 0.705 |

| Dysphonia | 12 (23) | 28 (25) | 0.790 |

| Sore throat | 7 (13) | 17 (15) | 0.772 |

| Isolated laryngopharyngeal symptoms, n (%) | 7 (13) | 45 (37) | 0.020 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carrillo-Rojas, J.I.; Zavala-Villegas, S.; Morales-Osorio, G.; García-García, F.D.; González-Navarro, M.; Mendoza-Martínez, V.M.; Bueno-Hernández, N. Accuracy of COuGH RefluX Score as a Predictor of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) in Mexican Patients with Chronic Laryngopharyngeal Symptoms: A Cross-Sectional Study. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 636. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15050636

Carrillo-Rojas JI, Zavala-Villegas S, Morales-Osorio G, García-García FD, González-Navarro M, Mendoza-Martínez VM, Bueno-Hernández N. Accuracy of COuGH RefluX Score as a Predictor of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) in Mexican Patients with Chronic Laryngopharyngeal Symptoms: A Cross-Sectional Study. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(5):636. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15050636

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarrillo-Rojas, Javier Ivanovychs, Salvador Zavala-Villegas, Guadalupe Morales-Osorio, Fausto Daniel García-García, Mauricio González-Navarro, Viridiana Montsserrat Mendoza-Martínez, and Nallely Bueno-Hernández. 2025. "Accuracy of COuGH RefluX Score as a Predictor of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) in Mexican Patients with Chronic Laryngopharyngeal Symptoms: A Cross-Sectional Study" Diagnostics 15, no. 5: 636. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15050636

APA StyleCarrillo-Rojas, J. I., Zavala-Villegas, S., Morales-Osorio, G., García-García, F. D., González-Navarro, M., Mendoza-Martínez, V. M., & Bueno-Hernández, N. (2025). Accuracy of COuGH RefluX Score as a Predictor of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) in Mexican Patients with Chronic Laryngopharyngeal Symptoms: A Cross-Sectional Study. Diagnostics, 15(5), 636. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15050636