Cross-Cultural Adaptation and Validation of the Malayalam Version of the Vocal Tract Discomfort Scale

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

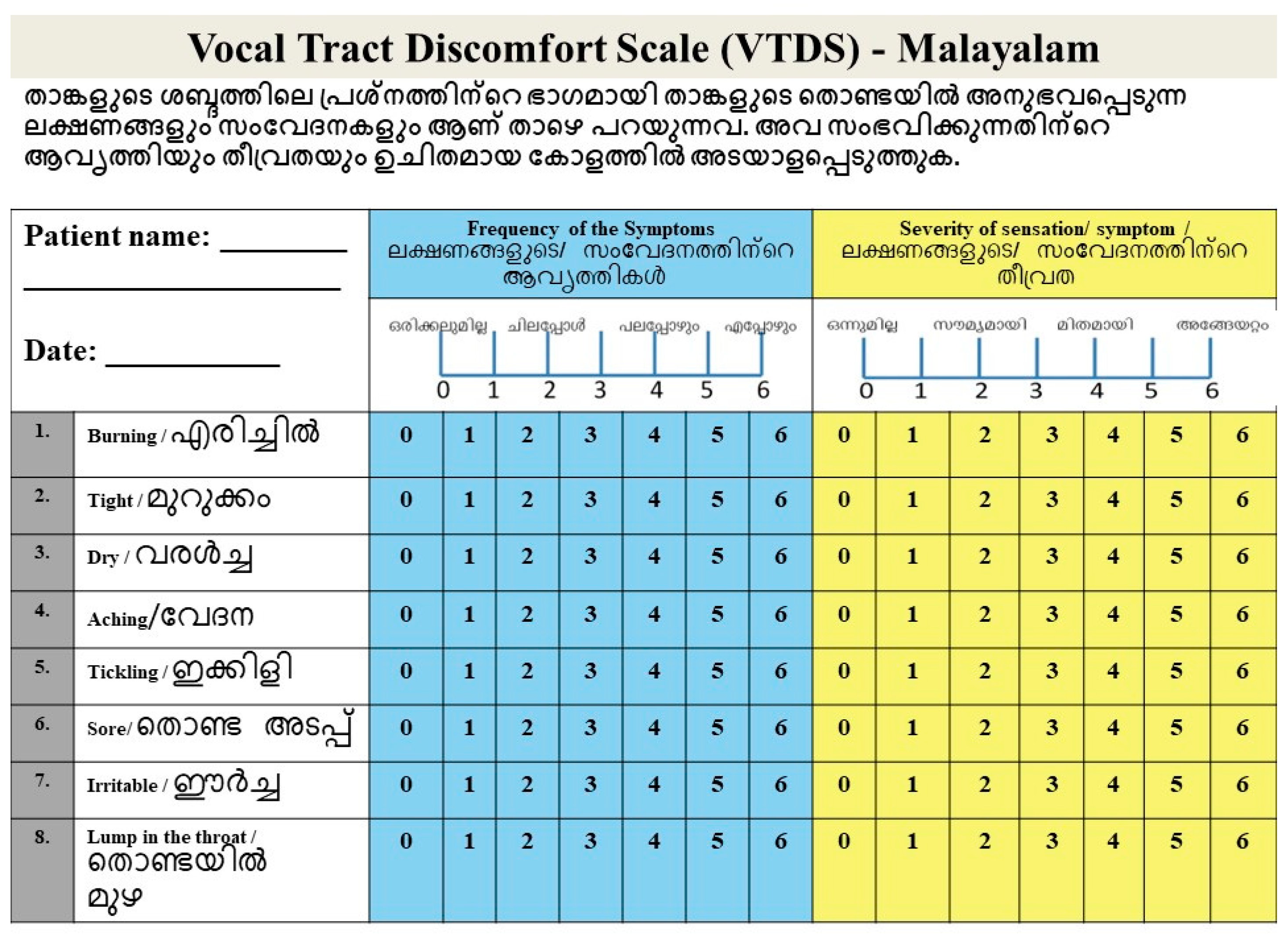

2.1. Phase I

2.2. Phase II

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Internal Consistency of VTDS-M

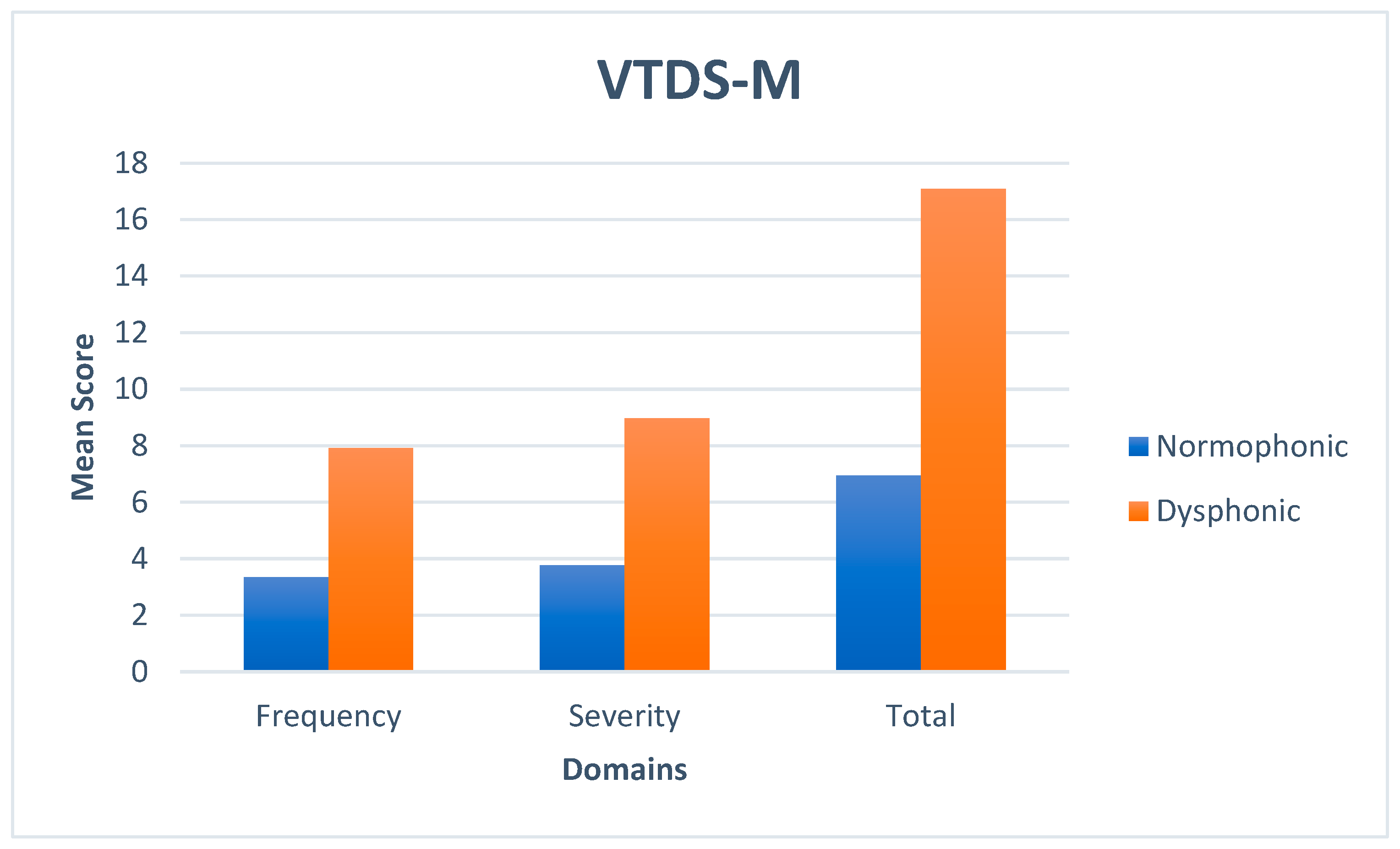

3.2. VTDS-M and VHI-M Scale Scores

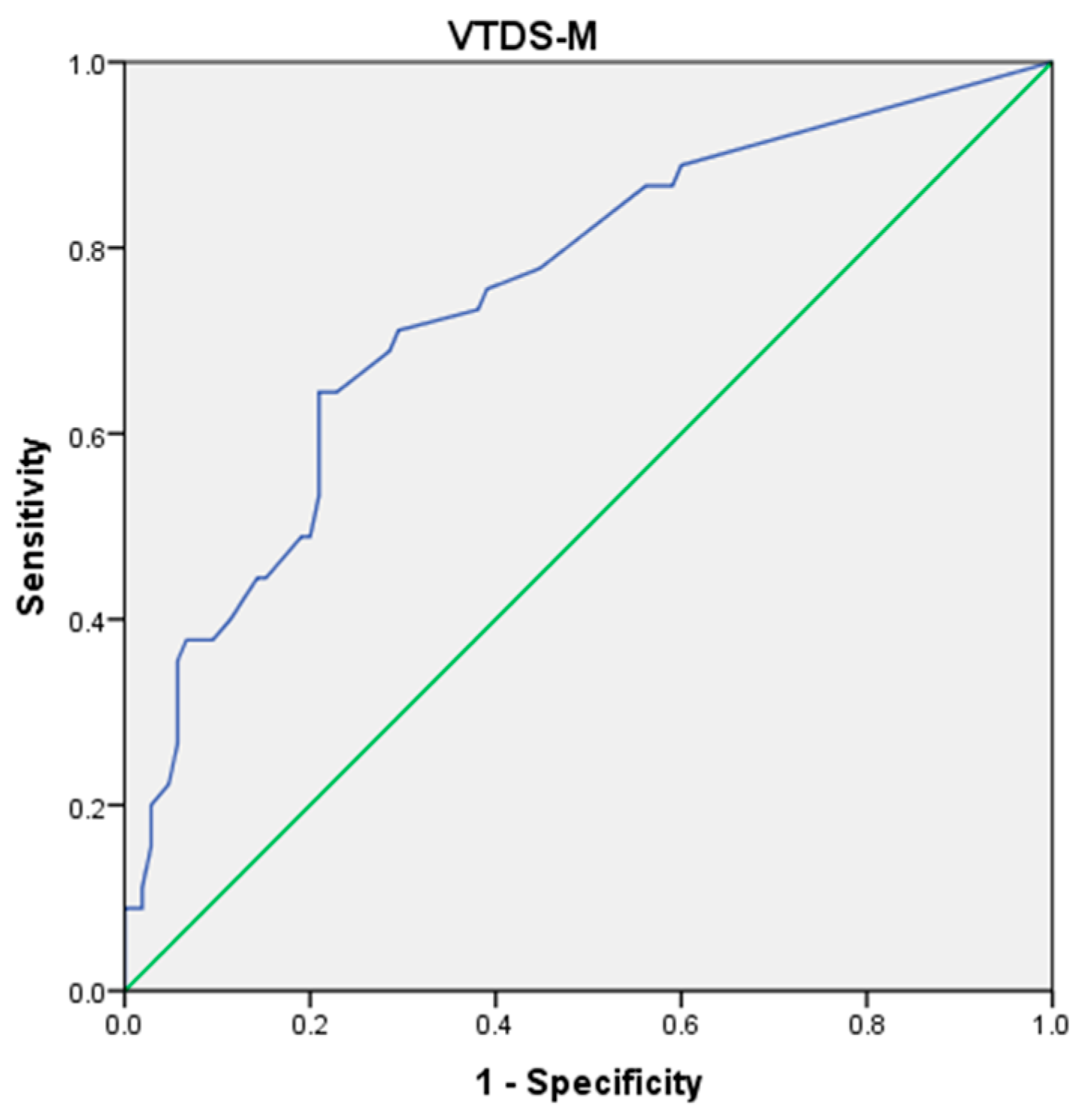

3.3. Diagnostic Accuracy of VTDS-M

3.4. Relationship Between VHI-M and VTDS-M

4. Discussion

4.1. Cross-Cultural Translation and Adaptation

4.2. Internal Consistency of VTDS-M

4.3. Diagnostic Accuracy of VTDS-M

4.4. Performance of Dysphonic and Normophonic Groups on VTDS-M and VHI-M Scale Scores

4.5. Relationship Between VHI-M and VTDS-M

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Wilson, J.A.; Deary, I.J.; Millar, A.; Mackenzie, K. The Quality of Life Impact of Dysphonia. Clin. Otolaryngol. 2002, 27, 179–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spector, B.C.; Netterville, J.L.; Billante, C.; Clary, J.; Reinisch, L.; Smith, T.L. Quality-of-Life Assessment in Patients with Unilateral Vocal Cord Paralysis. Otolaryngol.—Head Neck Surg. 2001, 125, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathieson, L. Vocal Tract Discomfort in Hyperfunctional Dysphonia. J. Voice 1993, 2, 40–48. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson, B.H.; Johnson, A.; Grywalski, C.; Silbergleit, A.; Jacobson, G.; Benninger, M.S.; Newman, C.W. The Voice Handicap Index (VHI): Development and Validation. Am. J. Speech Lang. Pathol. 1997, 6, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogikyan, N.D.; Sethuraman, G. Validation of an Instrument to Measure Voice-Related Quality of Life (V-RQOL). J. Voice 1999, 13, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, E.P.-M.; Yiu, E.M.-L. Voice Activity and Participation Profile: Assessing the Impact of Voice Disorders on Daily Activities. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2001, 44, 511–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deary, I.J.; Wilson, J.A.; Carding, P.N.; MacKenzie, K. VoiSS: A Patient-Derived Voice Symptom Scale. J. Psychosom. Res. 2003, 54, 483–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torabi, H.; Khoddami, S.M.; Ansari, N.N.; Dabirmoghaddam, P. The Vocal Tract Discomfort Scale: Validity and Reliability of the Persian Version in the Assessment of Patients With Muscle Tension Dysphonia. J. Voice 2016, 30, 711–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robotti, C.; Mozzanica, F.; Pozzali, I.; D’Amore, L.; Maruzzi, P.; Ginocchio, D.; Barozzi, S.; Lorusso, R.; Ottaviani, F.; Schindler, A. Cross-Cultural Adaptation and Validation of the Italian Version of the Vocal Tract Discomfort Scale (I-VTD). J. Voice 2019, 33, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darawsheh, W.B.; Shdaifat, A.; Natour, Y.S. Validation of the Arabic Version of Vocal Tract Discomfort Scale. Logop. Phoniatr. Vocology 2020, 45, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santi, M.A.; Romano, A.; Dajer, M.E.; Montenegro, S.; Mathieson, L. Vocal Tract Discomfort Scale: Validation of the Argentine Version. J. Voice 2020, 34, 158.e1–158.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukaschyk, J.; Abel, J.; Brockmann-Bauser, M.; Keilmann, A.; Braun, A.; Rohlfs, A.-K. Cross-Validation and Normative Values for the German Vocal Tract Discomfort Scale. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2021, 64, 1855–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.N.; Yoo, J.Y.; Han, J.H.; Park, Y.S.; Jung, D.Y.; Park, J.H. Transcultural Adaptation and Validation of the Korean Version of the Vocal Tract Discomfort Scale. J. Voice 2022, 36, 143.e15–143.e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alencar, S.; Santos, J.D.; Almeida, L.N.; Lopes, L.; Nascimento, J.A.D.; Almeida, A.A. Vocal Tract Discomfort Scale-Brazil (VTDS-BR): Validation Based on Internal Consistency, Reliability, and Accuracy. J. Voice 2024, S0892199724000730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, G.; Zambon, F.; Mathieson, L.; Behlau, M. Vocal Tract Discomfort in Teachers: Its Relationship to Self-Reported Voice Disorders. J. Voice 2013, 27, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, A.C.D.; Zambon, F.; Moreti, F.; Behlau, M. Desconforto Do Trato Vocal Em Professores Após Atividade Letiva. CoDAS 2017, 29, e20160045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Limoeiro, F.M.H.; Ferreira, A.E.M.; Zambon, F.; Behlau, M. Comparação Da Ocorrência de Sinais e Sintomas de Alteração Vocal e de Desconforto No Trato Vocal Em Professores de Diferentes Níveis de Ensino. CoDAS 2019, 31, e20180115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galletti, B.; Sireci, F.; Mollica, R.; Iacona, E.; Freni, F.; Martines, F.; Scherdel, E.P.; Bruno, R.; Longo, P.; Galletti, F. Vocal Tract Discomfort Scale (VTDS) and Voice Symptom Scale (VoiSS) in the Early Identification of Italian Teachers with Voice Disorders. Int. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2020, 24, e323–e329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porto, V.F.D.A.; Bezerra, T.T.; Zambon, F.; Behlau, M. Fatigue, Effort and Vocal Discomfort in Teachers after Teaching Activity. CoDAS 2021, 33, e20200067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darawsheh, W.B.; Natour, Y.S.; Sada, E.G. Applicability of the Arabic Version of Vocal Tract Discomfort Scale (VTDS) with Student Singers as Professional Voice Users. Logop. Phoniatr. Vocology 2018, 43, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, J.; Silverio, K.C.A.; Siqueira, L.T.D.; Ramos, J.S.; Brasolotto, A.G.; Zambon, F.; Behlau, M. Correlation between Vocal Tract Symptoms and Modern Singing Handicap Index in Church Gospel Singers. CoDAS 2017, 29, e20160187. [Google Scholar]

- D’haeseleer, E.; Quintyn, F.; Kissel, I.; Papeleu, T.; Meerschman, I.; Claeys, S.; Van Lierde, K. Vocal Quality, Symptoms, and Habits in Musical Theater Actors. J. Voice 2022, 36, 292.e1–292.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tohidast, S.A.; Mansuri, B.; Memarian, M.; Ghobakhloo, A.H.; Scherer, R.C. Voice Quality and Vocal Tract Discomfort Symptoms in Patients With COVID-19. J. Voice 2024, 38, 542.e29–542.e33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeedi, M.; Yadegari, M.; Aghadoost, S.; Naderi, M. Vocal Tract Discomfort and Voice Handicap Index in Patients Undergoing Thyroidectomy. Logop. Phoniatr. Vocology 2022, 47, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devadas, U.; Jose, N.; Gunjawate, D. Prevalence and Influencing Risk Factors of Voice Problems in Priests in Kerala. J. Voice 2016, 30, 771.e27–771.e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, U.K.; Raj, M.; Antony, L.; Soman, S.; Bhaskaran, R. Prevalence of Voice Disorders in School Teachers in a District in South India. J. Voice 2021, 35, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, U.; Sheejamol, V.; Cherian, M.P. Validation of Malayalam Version of the Voice Handicap Index. Int. J. Phonosurg. Laryngol. 2012, 2, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athira, U.R.; Devadas, U. Adaptation and Validation of Vocal Fatigue Index (VFI) to Malayalam Language. J. Voice 2020, 34, 810.e19–810.e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, L.W.; De Oliveira Florencio, V.; Silva, P.O.C.; Da Nóbrega E Ugulino, A.C.; Almeida, A.A. Vocal Tract Discomfort Scale (VTDS) and Voice Symptom Scale (VoiSS) in the Evaluation of Patients With Voice Disorders. J. Voice 2019, 33, 381.e23–381.e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaton, D.E.; Bombardier, C.; Guillemin, F.; Ferraz, M.B. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine 2000, 25, 3186–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perkins, N.J.; Schisterman, E.F. The Youden Index and the optimal cut-point corrected for measurement error. Biomed. J. J. Math. Methods Biosci. 2005, 47, 428–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luyten, A.; Bruneel, L.; Meerschman, I.; D’haeseleer, E.; Behlau, M.; Coffé, C.; Van Lierde, K. Prevalence of Vocal Tract Discomfort in the Flemish Population Without Self-Perceived Voice Disorders. J. Voice 2016, 30, 308–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Scale | Domains | Normophonic Group | Dysphonic Group | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| VTDS-M | Frequency | 3.352 | 3.95 | 7.911 | 5.41 |

| Severity | 3.771 | 5.02 | 8.977 | 7.13 | |

| Total | 6.952 | 8.56 | 17.089 | 12.73 | |

| VHI-M | Functional | 3.281 | 2.80 | 5.533 | 4.33 |

| Physical | 2.15 | 3.46 | 7.133 | 6.75 | |

| Emotional | 0.342 | 1.099 | 2.044 | 3.75 | |

| Total | 5.733 | 5.79 | 14.822 | 12.00 | |

| Scale | Cut-Off Values | AROC | Sensitivity | Specificity | Youden Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VTDS-M | 11.5 | 0.749 ** | 64.4% | 79.0% | 0.434 |

| VTDS-M Frequency | 5.5 | 0.748 ** | 62.2% | 77.1% | 0.393 |

| VTDS-M Severity | 5.5 | 0.743 ** | 64.4% | 78.1% | 0.425 |

| VTDS-M | VTDS-M | VHI-M | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Severity | Total | Functional | Physical | Emotional | Total | |

| Frequency | 1 | 0.896 * | 0.954 * | 0.261 * | 0.525 * | 0.368 * | 0.499 * |

| Severity | 0.896 * | 1 | 0.942 * | 0.187 | 0.546 * | 0.378 * | 0.488 * |

| Total | 0.954 * | 0.942 * | 1 | 0.240 * | 0.584 * | 0.420 * | 0.536 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ravi, S.K.; Shabnam, S.; Thupakula, S.; Narne, V.K.; Yerraguntla, K.; Almudhi, A.; Madathodiyil, I.; Sajan, F.; Jacob, K.R. Cross-Cultural Adaptation and Validation of the Malayalam Version of the Vocal Tract Discomfort Scale. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 259. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15030259

Ravi SK, Shabnam S, Thupakula S, Narne VK, Yerraguntla K, Almudhi A, Madathodiyil I, Sajan F, Jacob KR. Cross-Cultural Adaptation and Validation of the Malayalam Version of the Vocal Tract Discomfort Scale. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(3):259. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15030259

Chicago/Turabian StyleRavi, Sunil Kumar, Srushti Shabnam, Saraswathi Thupakula, Vijaya Kumar Narne, Krishna Yerraguntla, Abdulaziz Almudhi, Irfana Madathodiyil, Feby Sajan, and Kochette Ria Jacob. 2025. "Cross-Cultural Adaptation and Validation of the Malayalam Version of the Vocal Tract Discomfort Scale" Diagnostics 15, no. 3: 259. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15030259

APA StyleRavi, S. K., Shabnam, S., Thupakula, S., Narne, V. K., Yerraguntla, K., Almudhi, A., Madathodiyil, I., Sajan, F., & Jacob, K. R. (2025). Cross-Cultural Adaptation and Validation of the Malayalam Version of the Vocal Tract Discomfort Scale. Diagnostics, 15(3), 259. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15030259